Abstract

This study tests the predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms and examines the mediating roles of social competence, parent-child conflicts, and academic achievement. Using youth-, parent-, and teacher-reported longitudinal data on a sample of 523 boys and 460 girls from late childhood to early adolescence, we found evidence for pathways between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms in both directions. Parent-child conflict, but not social competence and academic achievement, was found to be a significant mediator such that externalizing behaviors predicted parent-child conflicts, which in turn, predicted internalizing symptoms. Internalizing symptoms showed more continuity during early adolescence for girls than boys. For boys, academic achievement was unexpectedly, positively predictive of internalizing symptoms. The results highlight the importance of facilitating positive parental and caregiver involvement during adolescence in alleviating the risk of co-occurring psychopathology.

Keywords: externalizing, internalizing, parent-child conflict, co-occurrence, mediators

Co-occurrence of externalizing and internalizing symptoms among youth is common, with rates of co-occurrence higher than expected by chance (Caron & Rutter, 1991). Externalizing behaviors describe a range of disruptive and dysregulated behaviors such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, non-compliance, hostility, aggression, and delinquency. On the other hand, internalizing symptoms are indicative of inwardly directed distress related to depression and anxiety. Examples are crying, loneliness, worrying, feeling guilty, and having trouble sleeping. The predictive and temporal associations between these two types of problems have been the focus of several studies (Ingoldsby, Kohl, McMahon, & Lengua, 2006; Kiesner, 2002; Wiesner, 2003). Mediating variables that may account for the association between externalizing and internalizing symptoms have also been proposed and evaluated, such as social competence (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2010; Obradović & Hipwell, 2010), peer relation difficulties (Gooren, Van Lier, Stegge, Terwogt, & Koot, 2011; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003; Van Lier & Koot, 2010), and academic achievement (Masten et al., 2005; Moilanen, Shaw, & Maxwell, 2010).

Although not entirely consistent across studies, evidence has been found for pathways between externalizing and internalizing problems in both directions. Controlling for initial levels of internalizing symptoms, several studies found that externalizing behaviors were predictive of internalizing symptoms during childhood (Gooren et al., 2011; Moilanen et al., 2010) and adolescence (Capaldi, 1992; Kiesner, 2002; Obradović & Hipwell, 2010; Wiesner, 2003) but others did not (Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Ingoldsby et al., 2006; Van Lier & Koot, 2010). Identifying possible reasons for these discrepant results is difficult given that studies have focused on different gender populations, developmental periods, and longitudinal time spans. However, it appears that studies with significant findings usually tested the longitudinal associations within a two-year span while those which did not find significant associations used a longer period of between two to six years. The shorter term predictive power of externalizing behaviors suggests that the risk effects of externalizing behaviors on internalizing symptoms may be more discernible within shorter periods of time. Although externalizing behaviors may contribute to increased moodiness, sadness, and low self-esteem in the shorter term, these do not necessarily translate to the prediction of more chronic or long-lasting internalizing symptoms. The increased proximal risk for internalizing symptoms may be due to the more immediate ramifications of externalizing behavior, such as peer rejection or reprimands and punishment from parents and teachers.

By comparison, less evidence has been found for the reverse pathway from internalizing symptoms to externalizing behaviors. The two studies supporting this pathway had used adolescent samples followed over 2–4 years (Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Wiesner, 2003). On the other hand, two others which did not find supportive evidence had used childhood and early adolescence samples (Gooren et al., 2011; Ingoldsby et al., 2006). Thus, these studies collectively suggest that the internalizing to externalizing pathway may be more likely during adolescence than during childhood. This may in part be due to the fact that for some youth, internalizing symptoms become more stable and serious during adolescence (Hammen & Rudolph, 2003) and those who experience internalizing symptoms may act out in response to their distress (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006).

One theory to explain the links between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms is the failure theory (Kiesner, 2002). In its early formulation, the failure theory hypothesized that the disruptive, impulsive, and aggressive nature of externalizing behaviors interferes with the development of social skills and academic competence (termed as dual failure by Patterson & Stoolmiller, 1991), leading to poor peer and family relationships and poor academic performance. The lack of social competence and appropriate social learning opportunities, together with negative reactions from others, were suggested to lead to further negative outcomes and low self-esteem, contributing to increasing vulnerabilities for internalizing symptoms (Capaldi, 1991). In subsequent formulations of the theory, it was hypothesized that as youth progressed in development, internalizing symptoms would further aggravate initial externalizing behaviors (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1998; Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). Depression and associated symptoms such as irritability and distractibility may reduce concerns for adverse consequences, impede problem-solving skills, and result in interpersonal conflicts and antisocial behaviors (Capaldi, 1991; Oland & Shaw, 2005). These developmental pathways have also been described as cascading effects, a concept that refers to the transactions occurring between the individual and environment with effects spreading within and across social-emotional, behavioral, and cognitive functioning, as well as across developmental periods. Multiple pathways are encompassed in cascade models, including those that are direct and unidirectional, direct and bidirectional, and indirect (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Applying cascading effects to co-occurring externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms suggests that one type of impairment may create a vulnerable context for the other to develop (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Hence, in this formulation, the externalizing to internalizing and the internalizing to externalizing pathways are both plausible explanatory models for the co-occurrence of symptoms.

Given that these theories do not directly compare the likelihood of the pathways, that evidence for both pathways is available, and that inconsistent results have been found, the directions of the associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms during different developmental periods remains to be clarified. However, more studies have reported significant externalizing to internalizing pathways (Capaldi, 1992; Gooren et al., 2011; Kiesner, 2002; Moilanen et al., 2010; Obradović & Hipwell, 2010; Wiesner, 2003). Developmentally, the onset of externalizing behaviors typically occurs earlier than the onset of depressive symptoms (Wolff & Ollendick, 2006). The median ages of onset for impulse-control and mood disorders have been reported to be 11 (interquartile range of 8) and 30 years (interquartile range of 25), respectively (Kessler et al., 2005). Compared to children with internalizing symptoms, those with externalizing behaviors are more likely to experience greater functional impairment, including poorer school performance, more social problems, and more peer rejection (Gooren et al., 2011; Ingoldsby et al., 2006). These difficulties may trigger cascading effects to other symptom domains. For example, when rejected children receive negative feedback and responses in their social encounters, they may develop low self-esteem and become at risk of internalizing symptoms (Cole, Jacquez, & Maschman, 2001; Fanti & Henrich, 2010; Gooren et al., 2011).

The failure theory and cascading models linking externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms suggest that social competence, academic competence, and interpersonal relations may function as mediating factors. A handful of studies have investigated these mediation effects (Bornstein et al., 2010; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003; Masten et al., 2005; Moilanen et al., 2010; Van Lier & Koot, 2010; Van Lier et al., 2012) but only one longitudinal study has tested these variables simultaneously (Van Lier et al., 2012).

In each of the following sections, evidence of longitudinal predictive associations are reviewed since significant predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and mediating variables and between internalizing symptoms and mediating variables are considered necessary though insufficient evidence for mediation. These studies will provide supportive evidence for possible mediation if mediation studies are not available. Next, studies that have explicitly tested for mediation by each potential mediating variable are reviewed. Relevant gender-related findings are highlighted when available.

Social Competence

Social competence is a broadly defined characteristic that encompasses interpersonal skills such as emotional and behavioral self-regulation, social problem-solving, communication skills, and prosocial relationships with peers and adults. According to several longitudinal studies, externalizing behaviors contribute to poor social competence, low peer status, peer rejection, and diminished peer support (Campbell, Spieker, Vandergrift, Belsky, & Burchinal, 2010; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Kiesner, 2002; Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004). In addition, poor social competence is generally found to be a risk factor for both externalizing and internalizing problems (Boots, Wareham, & Weir, 2011; Bornstein et al., 2010; Burt, Obradović, Long, & Masten, 2008; Cole, Martin, Powers, & Truglio, 1996). The link from poor social competence to externalizing behaviors is further corroborated by experimental evidence showing that social skills training improves social behaviors and peer relations, and reduces externalizing behaviors (Cook et al., 2008). By comparison, less evidence is available to suggest that internalizing symptoms may lead to diminished social competence as measured by social and interpersonal problems and conflicts (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Mesman, Bongers, & Koot, 2001).

Support for the mediating role of social competence was found by Mesman and colleagues (2001) and more recently by Obradovic and Hipwell (2010), who controlled for prior levels of the measures, thereby providing a conservative test of longitudinal effects. Externalizing behaviors in 10-year old girls predicted less social competence at age 11, which in turn predicted more internalizing symptoms at age 12. In contrast, results from two other mediation studies, spanning ten years (Bornstein et al., 2010) and twenty years (Burt et al., 2008), did not show evidence of mediation by social competence.

Parent-Child Conflict

Even though no study has explicitly investigated the mediating role of parent-child conflict, empirical evidence supports associations of parent-child conflict with both externalizing and internalizing outcomes. Children who show early externalizing behaviors such as non-compliance and disruptive behaviors are likely to develop conflict-laden relationships with their parents (Campbell, Spieker, Vandergrift, Belsky, & Burchinal, 2010; R. Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009). Conversely, parent-child conflict and low family cohesion are also associated with later adolescent delinquency and violence (Boots et al., 2011; Klahr, Rueter, McGue, Iacono, & Burt, 2011; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004).

A variety of parenting and family environment variables are also associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence, including poor parent-child relationships, parent-child conflict, and low family support (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004; Stice et al., 2004). In addition, specific interactional factors such as negativity and aggression contribute to vulnerability for depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents (Schwartz et al., 2012). On the other hand, there is comparatively less evidence that depressive symptoms may contribute to parent-child conflict even though several studies have documented high levels of conflict in homes of depressed youth and during parent-child interactions (Hamilton, Asarnow, & Tompson, 1997; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004). As internalizing symptoms are often associated with dysfunctional problem solving, coping, and emotional regulation, these may affect children’s social functioning and result in conflicts with parents (Kaslow, Deering, & Racusin, 1994; McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007). Overall, while the predictive associations between parent-child conflict and externalizing and internalizing problems are fairly well supported, the directions of these associations are less clear.

Academic Achievement

Externalizing behaviors have been found to predict low academic achievement, poor school adjustment, and reading problems (Campbell, Spieker, Burchinal, & Poe, 2006; X. Chen & Rubin, 1997; Morgan, Farkas, Tufis, & Sperling, 2008). Children with externalizing behaviors often exhibit poor attention, impulsivity, non-compliance, and reduced engagement in learning tasks (Campbell et al., 2006), which often results in poor learning and academic performance. Studies have also found that low academic functioning, such as poor early literacy and reading problems also predicts later increase in externalizing behaviors (Ansary & Luthar, 2009; Morgan et al., 2008). Persistent academic difficulties such as reading problems may frustrate children and increase their acting-out and withdrawal behaviors in order to avoid reading and learning tasks (Cook et al., 2012). Furthermore, evidence has accumulated to support a possible bidirectional relationship between academic functioning and externalizing behavior (Morgan et al., 2008; Cook et al., 2012).

On the other hand, the association between internalizing symptoms and academic performance has been less consistent (Moilanen et al., 2010; Patterson & Stoolmiller, 1991). Even though some studies found that early internalizing symptoms predicted poor academic achievement (Flook, Repetti, & Ullman, 2005; Hishinuma, McArdle, & Chang, 2012; Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2000), others did not (Ansary & Luthar, 2009; Cole et al., 1996; Patterson & Stoolmiller, 1991). Conversely, for the longitudinal association from poor academic achievement to internalizing symptoms, some results were significant (Morgan et al., 2008; Roeser et al., 2000; Herman, Lambert, Reinke, & Ialongo, 2008), but not others (Ansary & Luthar, 2009; Cole et al., 1996; Hishinuma et al., 2012; Lehtinena, Räikkönena, Heinonena, Raitakari, & Keltikangas-Järvinena, 2006). Significant associations between internalizing and academic performance have been attributed to symptoms of depression such as concentration problems, negative self-evaluations, and pessimism causing poor achievement (Roeser, Van der Wolf, & Strobel, 2001) or repeated academic failure resulting in negative emotions and attributions and depressive symptoms (X. Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1995; Herman et al., 2008; Morgan et al., 2008; Roeser et al., 2000)

Mediation studies suggest that academic competence and achievement may be significant mediators of the association between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms (Masten et al., 2005; Moilanen et al., 2010; Van Lier et al., 2012). Early externalizing behaviors were found to impede children’s academic functioning and development. With low academic attainment, they are likely to receive negative feedback from parents and teachers which are stressors inducing negative cognitions and moods, thus leading to an increase in internalizing symptoms (Masten et al., 2005; Moilanen et al., 2010).

Even though gender differences were not found in these mediation studies (Masten et al., 2005; Moilanen et al., 2010; Van Lier et al., 2012), there is evidence that girls may be more vulnerable to academic failure and consequently, be more at-risk of developing internalizing symptoms compared to boys. One study found that low academic achievement at ages 9 and 10 predicted school failure experiences (i.e., suspensions, expulsions, not graduating on time) in adolescence and the likelihood of a major depressive episode in young adulthood for girls but not for boys (McCarty et al., 2008). Compared to boys, girls tend to underestimate their academic competence (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Fier, 1999) and are more affected by others’ negative evaluations of their academic competence (Cole & Martin, 1997). As a result, they experience a greater reduction of global self-worth and steeper increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms in relation to poor academic performance, compared to boys (Pomerantz, Saxon, & Altermatt, 2002).

Goals for the Current Study

Mediation studies in this area have been limited by focusing on single mediators and using childhood samples, with little extension into adolescence. Further, gender differences in the mechanisms linking externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms are understudied. For example, out of about ten studies, four of them focused only on boys (Beyers & Loeber, 2003; Capaldi, 1992; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Moilanen et al., 2010) and one did not test for gender differences (Kiesner, 2002). Of the five studies which tested for gender differences, one found significant results in an adolescent sample (Wiesner, 2003) but another did not (Ingoldsby et al., 2006). Three others also did not find any gender difference in childhood samples (Gooren et al., 2011; Van Lier & Koot, 2010; Van Lier et al., 2012).

It is possible that gender differences in these mechanisms are a function of development, with more similarities between boys and girls during childhood than adolescence. Early adolescence marks the beginning of gender role intensification (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000). A combination of factors, including biological (pubertal timing and development), affective (temperament), and cognitive (negative cognitive style, body consciousness, and rumination) factors are likely to interact with the emergence of new challenges to result in gender differences in coping and adjustment (Hyde, Mezulis, & Abramson, 2008). Additionally, vulnerabilities for psychopathology also becomes markedly different, with higher male preponderance for conduct problems and higher female preponderance for internalizing problems from adolescence onward (Zahn-Waxler, Crick, Shirtcliff, & Woods, 2006).

The first objective of the current study was to evaluate the temporal and predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms in a sample followed from late childhood to early adolescence so as to determine if one type of problem is more likely to lead to another. The second objective was to simultaneously evaluate the roles and unique effects of social competence, parent-child conflict, and academic achievement as mediators in the predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms, as well as to test for gender differences. A 5-year period from fourth to eighth grade was chosen to identify meaningful longitudinal effects of externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms across an important transition period from late childhood to early adolescence.

We hypothesized that externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms would show predictive associations with each other and that externalizing behaviors were more likely to predict internalizing symptoms. As gender differences in these longitudinal associations have not been clearly identified, analyses to test for the moderating effects of gender were considered to be exploratory. Given the theoretical postulations of cascading effects and the empirical evidence to date, social competence, parent-child conflict, and academic achievement were hypothesized to play significant mediating roles between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms. In general, more externalizing behaviors or internalizing symptoms at an earlier time point were expected to predict more parent-child conflict, poorer social competence, and lower academic achievement, which in turn would predict more problems in the other area at a later time point. Given the previous finding that girls are more likely to develop internalizing symptoms as a result of poor academic functioning, we hypothesized that girls would be more affected by low academic achievement than boys.

Method

Sample

The sample is from the Raising Healthy Children project (RHC; Catalano et al., 2003), which is both a study of the etiology of prosocial and antisocial behavior. This study has a trial of a multicomponent preventive intervention nested within it. Detailed descriptions of the intervention and evaluation results are reported elsewhere (Brown, Catalano, Fleming, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2005; Catalano et al., 2003; Haggerty, Fleming, Catalano, Harachi, & Abbott, 2006). Participants and their families were recruited from 10 schools in a suburban Pacific Northwest school district when the students were in first and second grade. The project enrolled 1,040 students and their families in 1993 and 1994.

To be included in the analytic sample of the current study, cases that had little or no information to help model estimates were dropped and students were required to have non-missing data on family income for at least 2 years when they were in second through eighth grade, as well as to have data on externalizing, internalizing, or mediating measures. This resulted in an analytic sample of 983 (523 boys and 460 girls). No significant differences (p > .05) were found between the included and excluded participants with respect to gender, ethnicity, low-income status of the students’ families at the beginning of the project, or experimental condition. Based on participants’ self-report of race and ethnicity, the racial composition of the sample was 75.3% White, 3.5% Black, 6.7% Asian or Pacific Islander, 2.3% Native American, and 12.2% mixed; 8.6% of the sample reported that they were Hispanic.

Procedure

Prior to data collection, parents provided written consent for their children’s participation and students provided assent. Data were collected in the spring of each year using student and teacher surveys. Student surveys were administered in a group format or individually during regular school hours. Students received tokens in the form of gifts, gift cards, or cash for completing the surveys each year. Between fourth through eighth grade, over 95% of the students in the analytic sample were surveyed annually. Parent surveys were administered using phone interviews for which they received monetary incentives of between $25 and $50. Parent survey completion rates for the analytic sample were 90% or above. Teacher mail-in surveys for individual students were completed by their primary teachers in elementary schools and Language Arts teachers in middle schools. Teacher surveys were completed for over 92% of the analytic sample each year between fourth and eighth grade.

Measures

Externalizing

A scale of externalizing behavior was based on 13 teacher-report items from the Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation-Revised (Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991). They covered a range of disruptive and antisocial behaviors that teachers could observe in the school setting. Examples of the items are “can’t sit still,” “argues a lot,” “talks back to adults, is disrespectful,” “threatens people,” and “fights.” Each item was rated on a 3-point scale: 1 = rarely true, 2 = sometimes true, and 3 = often or always true. Externalizing scale scores were based on the mean across items, with higher scores indicating more externalizing behaviors. The internal consistency of the scale, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranged from .89 to .91 for boys and from .87 to .90 for girls. Measures of externalizing behaviors were calculated for three time points. At the first time point, the mean of externalizing scale scores when students were in fourth and fifth grade (Grades 4/5) was used. These scores correlated at r =.62 (p < .01). The second time point was the mean of the scale scores at sixth and seventh grades (Grades 6/7; r =.55, p < .01). The third time point was the scale score at eighth grade.

Internalizing

The internalizing scale was based on 6 student-report items derived from the Seattle Personality Questionnaire that measured students’ depressive symptoms (Greenberg & Kusche, 1990; Kusche & Greenberg, 1988). The items asked about students’ cognitive, affective, and somatic symptoms that were indicative of the depressive phenomena. For example, the item “Do you feel upset about things a lot?” provided an indication of depressed mood. “Do you feel like crying a lot of the time?” and “Do you feel that you do/did things wrong a lot at school?” suggest anxious/depressed syndrome. In addition, “Do you have trouble falling asleep?” “Do you feel tired a lot?” and “Do you want to be by yourself a lot?” are similar to items on more commonly used self-report measures of child depressive symptoms, such as the Childhood Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale: 1 = “YES!”, 2 = “yes”, 3 = “no”, and 4 = “NO!” Items were reverse coded and scale scores were based on the mean score across items, with higher scores indicating more internalizing symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .68 to .71 for boys and .75 to .80 for girls. Measures of internalizing symptoms were calculated for three time points from the mean of fourth and fifth grades internalizing scale scores (r = .61, p < .01), the mean of sixth and seventh grades scale scores (r = .60, p < .01), and the eighth grade scale score. This six-item internalizing measure was found to correlate significantly with another four-item measure of anxiety administered concurrently (r= .51 – .55 for boys and r= .52 – .60 for girls), thus providing some evidence of validity.

Social competence

The social competence scale from the Walker-McConnell scale of social competence and social adjustment (Walker, Stieber, & Eisert, 1991) was composed of seven items measuring parent-report of students’ broad interpersonal skills such as emotional self-regulation, positive communication, social cognition, social problem-solving, and prosocial relationships with family members and peers. Examples include “Student controls (his/her) temper when there is a disagreement”, “student listens to others’ points of view”, and “student resolves problems with friends or brother/sisters on his/her own.” Response options for all items are 1 = “a lot”, 2 = “quite a bit/quite a few”, 3 = “some”, 4 = “a little”, and 5 = “not at all.” Items were reverse scored and averaged so that higher scale scores indicated higher social competence. The internal consistencies of the scale ranged from .80 to .84 for boys and .83 to .85 for girls. Two measures of social competence were obtained from the mean of scale scores at fourth and fifth grades (r = .67, p < .01), and at sixth and seventh grades (r = .66, p < .01).

Parent-child conflict

A scale of parent-child conflict was based on three student-report items that asked if students got into arguments or disagreements with their parents about getting ready for school, helping out at home, and completing homework. The items had a 4-point rating scale options: “YES!”, “yes”, “no”, and “NO!” The items were reverse coded and averaged to form a scale score with higher scores indicating higher levels of parent-child conflict. The internal consistencies of the scale ranged from α = .65 to .75 for boys and α = .64 to .69 for girls. Measures of parent-child conflict were based on the mean of scores at fourth and fifth grades (r = .47, p < .01), as well as the mean of scores at sixth and seventh grades (r = .43, p < .01).

Academic achievement

Students’ academic performance was based on standardized testing at Grades 4 and 7. The Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills (CTB, 1990) was administered to all fourth graders in the Washington State during that time and the academic achievement score for the current study was obtained from the average composite of the reading and math scores (r = .73, p < .01). At seventh grade, the achievement score was the average composite of the reading and math scores (r = .65, p < .01) of the Washington Assessment of Student Learning (WASL; Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, 2002). The WASL was developed as a criterion referenced test, designed to assess mastery of basic academic skills and knowledge. Scores have an approximate normal distribution and display external validity with reference to the nationally administered Iowa Test of Educational Development, with correlations of over .7 between scores on similar topic areas for tests administered a year apart. The correlation between CTB and WASL scores was .63 (p < .01). The fourth and seventh grade achievement scores were rescaled by a factor of 1/100 so that their variances did not differ from other measures by more than 10, to facilitate model convergence (Kline, 2011).

Covariates

Family income

Average family income was considered a potential confound in the relationship between externalizing and internalizing symptoms and was therefore included as a covariate. Parents reported their annual income each year using eight ordered categories based on income from (1) less than $10,000 to (8) more than $70,000. This measure was based on the average of parent report of household income across second to eighth grades.

Race/Ethnicity

Preliminary analyses found that Asian/Pacific Islander students (7% of the sample) had relatively low levels of externalizing behaviors compared to other racial/ethnic groups and African American and Latino students (6% of sample) had relatively low standardized test scores compared to other groups. Hence, we controlled for race/ethnicity using dummy variables to represent whether participants were (a) Asian/Pacific Islander or (b) African American/Latino.

Analyses

After examining the descriptive data on all measured variables including gender differences and overall correlations among the variables, path modeling was used to investigate the pathways between externalizing and internalizing symptoms across three time points – Grades 4/5, Grades 6/7, and Grade 8. At Grade 4/5, scores were the average composites of scores at Grade 4 and Grade 5, except for the academic achievement score at Grade 4 only. Similarly, at Grade 6/7, scores were the average composites of scores at Grade 6 and Grade 7, except for the academic achievement score at Grade 7 only. The scores were combined to make three time points for testing specific mediation hypotheses.

Average family income and the dummy variables of race/ethnicity were entered into all the models as covariates. Auto-regressive paths were specified to predict the later measures from their earlier counterparts to account for stability in measures across time points. Specific covariation among the measures at each time point was also specified to account for concurrent relations that may arise, such as that due to similar informant.

The first set of models were simple cross-lagged models for testing the cross-construct predictive associations between externalizing and internalizing symptoms while controlling for initial levels of symptoms and not including any mediating variables. The second set of models included the mediating variables with the specific objective of determining if indirect effects through mediating variables were significant. Models were fitted using Mplus 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011). The maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) estimator was used, as it makes adjustment for nonnormality and allows for use of cases with some missing data. Model fit was evaluated based on root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and comparative fit index (CFI). A model was considered to attain an adequate fit to the data when RMSEA was .06 or less or CFI was .95 or greater (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Multiple group models were used to test invariance of paths across gender groups (Kline, 2011). Modification indices were examined to determine the paths which could be unconstrained to improve model fit. A modification index estimates the amount by which the overall model chi-square statistic would be reduced if a fixed parameter was freely estimated (Kline, 2011). High modification indices were identified and freeing of the particular paths was considered only if it made theoretical sense and concerned hypotheses about gender differences. Subsequently, comparisons of nested models were based on significance level cutoffs for the scaled chi-square difference test reported by Satorra and Bentler (2001). To test the significance of indirect paths in the second set of models with mediating variables, the MODEL INDIRECT command was used (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011).

For most variables, less than 5% of the analytic sample was missing data. Exceptions to this were the externalizing measure at Grade 8 and academic achievement at Grades 4 and 7, which were missing data for 7.7%, 11.9%, and 18.7% of the sample, respectively. Missing data was handled using full information maximum likelihood which utilizes all available data and assumes that data was missing at random after taking nonmissing data into account.

Intervention condition was not related to the level of any measured variables, except average family income, r = .09, p < .01. Families in the intervention group reported higher average income than those in the control group. While controlling for income and race/ethnicity, multiple-group models were run by experimental condition for the model that included mediating variables to test for possible differences in covariance produced by the interventions. Results showed no significant difference between constrained and unconstrained models, ΔMLRχ2(73) = 71.13, p > .05. On this basis, participants from both conditions were included in the subsequent analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for all variables are provided separately for boys and girls in Table 1. Independent t-tests were used to compare differences on each measure across gender. Boys scored significantly higher than girls on externalizing behaviors at all three time points. Girls reported more internalizing symptoms than boys only at Grade 8. Girls were rated higher on social competence at Grades 4/5 and 6/7. Girls’ academic achievement was also higher than boys’ at Grade 7, but not at Grade 4. No significant gender differences were found on measures of parent-child conflict and average family income. All the distributions of the measured variables exhibited skewness and kurtosis values that were within acceptable limits (Skewness < 2.0; Kurtosis < 6.0), except for girls’ externalizing behaviors at Grade 6/7 (Skewness = 2.05, SE = .12; Kurtosis = 5.17, SE = .23), as well as Grade 8 (Skewness = 2.10, SE = .12; Kurtosis = 5.10, SE = .24).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrices of Measured Variables in Path Models for Boys and Girls

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Externalizing gr. 4–5 | --- | .64** | .53** | .32** | .24** | .17** | −.34** | −.36** | .25** | .22** | −.40** | −.32** | −.21** |

| 2.Externalizing gr. 6–7 | .67** | --- | .52** | .23** | .25** | .20** | −.34** | −.39** | .18** | .21** | −.34** | −.34** | −.21** |

| 3.Externalizing gr. 8 | .54** | .57** | --- | .21** | .19** | .18** | −.21** | −.27** | .12* | .18** | −.31** | −.27** | −.16** |

| 4.Internalizing gr. 4–5 | .23** | .17** | .12* | --- | .64** | .45** | −.28** | −.25** | .44** | .28** | −.18** | −.19** | −.10* |

| 5.Internalizing gr. 6–7 | .25** | .23** | .19** | .61** | --- | .68** | −.16** | −.21** | .32** | .46** | −.14** | −.16** | −.11* |

| 6.Internalizing gr. 8 | .04 | .08 | .07 | .40** | .54** | --- | −.15** | −.16** | .29** | .35** | −.09 | −.11* | −.08 |

| 7.Social comp. gr. 4–5 | −.39** | −.34** | −.27** | −.20** | −.24** | −.11* | --- | .76** | −.21** | −.13** | .24** | .15** | .11* |

| 8.Social comp. gr. 6–7 | −.37** | −.33** | −.26** | −.23** | −.26** | −.10* | .77** | --- | −.19** | −.15** | .21** | .10 | .13** |

| 9.Parent-child conflict gr. 4–5 | .17** | .14** | .12** | .32** | .24** | .14** | −.16** | −.15** | --- | .46** | −.10 | −.08 | −.09 |

| 10.Parent-child conflict gr. 6–7 | .21** | .19** | .17** | .27** | .35** | .29** | −.17** | −.19** | .45** | --- | −.10* | −.13* | .02 |

| 11.Acad. achievement gr. 4 | −.24** | −.23** | −.14** | −.07 | −.07 | .10* | .08 | .06 | −.06 | −.05 | --- | .63** | .29** |

| 12.Acad. achievement gr. 7 | −.31** | −.31** | −.30** | −.05 | −.09 | .07 | .06 | .07 | .02 | −.06 | .68** | --- | .25** |

| 13.Household income | −.23** | −.21** | −.08 | −.06 | −.09* | −.03 | .02 | .06 | −.03 | −.01 | .27** | .27** | --- |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

|

| Girls | 1.24 (0.30) |

1.22 (0.27) |

1.20 (0.27) |

2.03 (0.63) |

2.00 (0.60) |

2.05 (0.63) |

3.82 (0.59) |

3.88 (0.59) |

1.71 (0.70) |

1.88 (0.64) |

6.60 (0.44) |

3.83 (0.29) |

9.07 (3.21) |

| Boys | 1.40 (0.36) |

1.39 (0.34) |

1.34 (0.38) |

2.05 (0.57) |

2.01 (0.51) |

1.96 (0.53) |

3.70 (0.56) |

3.74 (0.56) |

1.70 (0.70) |

1.91 (0.64) |

6.59 (0.48) |

3.79 (0.31) |

9.06 (3.18) |

Note. gr. = grade, comp. = competence, Acad. = Academic. Correlations above the diagonal are for girls.

p < .05,

p < .01

Moderate stability was found for both externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms (rs > .40). For girls, externalizing and internalizing problems were positively and significantly correlated within and across time points. For boys, significant positive associations between externalizing and internalizing problems were found within time points at Grades 4/5 and Grades 6/7, but not at Grade 8. Similar to girls, the cross-time and cross-construct associations for boys were positive and significant, with the exception of the associations between Grade 8 internalizing symptoms and the measures of externalizing behaviors at different time points.

For girls, externalizing and internalizing symptoms at the three time points were significantly associated with all the mediating variables and household income with the exception of the associations of Grade 8 internalizing symptoms with Grade 4 academic achievement as well as with household income. Most of these associations were also significant for boys but measures of internalizing symptoms were not significantly associated with academic achievement, with the exception that Grade 4 academic achievement was unexpectedly positively associated with Grade 8 internalizing symptoms.

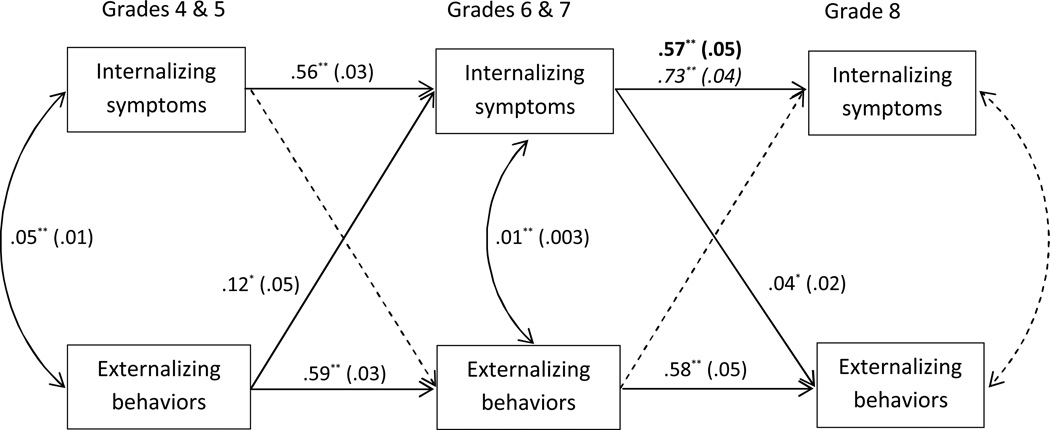

As shown in Figure 1, the first path model tested the relationships between internalizing symptoms and externalizing behaviors without considering potential mediators. The model was fitted to the data to investigate the cross-construct predictive associations between externalizing and internalizing symptoms without taking into account the potentially mediating variables. Two participants were excluded from this analysis because they had missing data for all the externalizing and internalizing measures in the first model. In this model, all the autoregressive and cross-lagged paths were estimated, including the covariances between residuals of the externalizing and internalizing measures at the three time points. This model attained a reasonable fit to the data (χ2(37, N = 981) = 98.00, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06).

Figure 1. Path model of associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms.

Paths from covariates of average family income and race/ethnicity are not shown. Solid lines represent statistically significant (p < .05) paths. Dashed lines were estimated but were not statistically significant. Numbers on significant paths are unstandardized estimates with standard errors in parentheses. For the path from internalizing symptoms at Grades 6 & 7 to internalizing symptoms at Grade 8, the estimates for boys are in bold and the estimates for girls are in italics. Fit statistics are χ2(24, N = 981) = 79.50, p < .01, CFI =.97, and RMSEA = .06. * p < .05, ** p < .01

Releasing the cross-gender constraint on the path from internalizing symptoms at Grade 6/7 to internalizing symptoms at Grade 8 improved model fit significantly (ΔMLRχ2(1) = 7.45, p < .01), reflecting greater stability in this construct across this time period for girls than boys (fit of the modified model: χ2(36, N = 981) = 90.23, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06). Evidence for reciprocal predictive relationships was found in that more externalizing behaviors at Grades 4/5 predicted more internalizing symptoms at Grades 6/7, which in turn predicted more externalizing behaviors at Grade 8. The standardized coefficients, which differ slightly by gender due to differences in variances across groups, are β = .09 (boys) and β = .06 (girls) for the first path and β = .05 (boys) and β = .07 (girls) for the second.

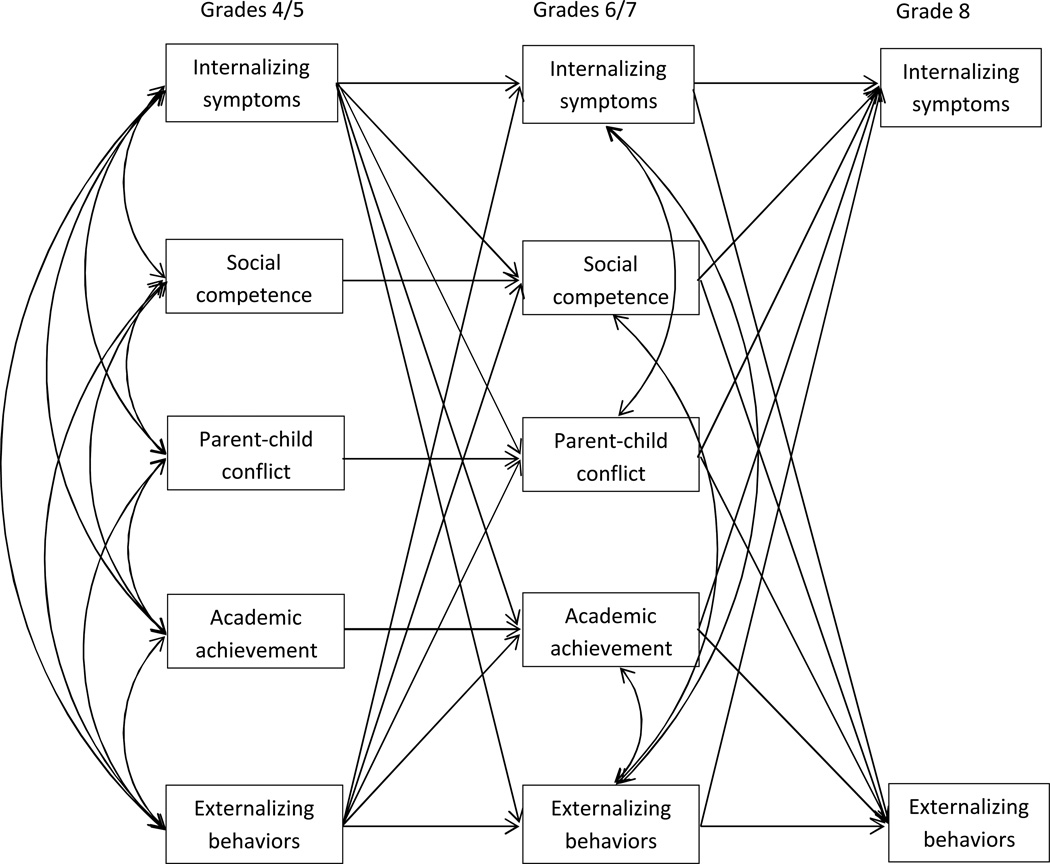

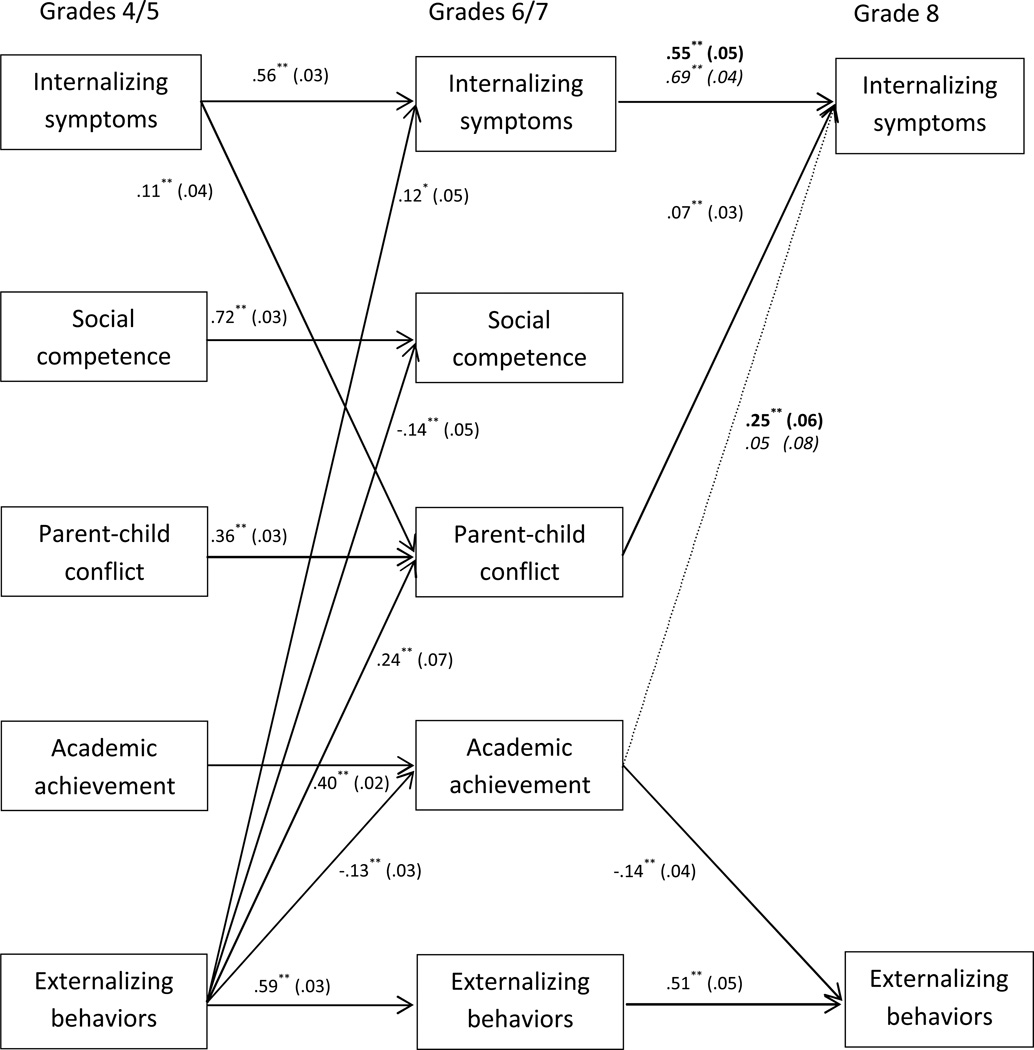

The next path model included mediating variables and was specified as shown in Figure 2. Externalizing and internalizing variables at Grades 4/5 predicted the mediating variables at Grades 6/7, which in turn predicted externalizing and internalizing problems at Grade 8. All the variables at Grades 4/5 were allowed to covary with one another while only the significant covariances among the residuals of the measures at Grades 6/7 and Grade 8 were included for parsimony. This model attained a good fit to the data (χ2(128, N = 983) = 193.53, p < .01, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03). After inspecting modification indices from the constrained multiple group model, it was found that, in addition to releasing the stability path for internalizing symptoms between Grades 6/7 and Grade 8, releasing the cross-gender constraint on the path from Grade 7 academic achievement to Grade 8 internalizing symptoms improved model fit (ΔMLRχ2(1) = 4.31, p < .05; fit of the modified model: χ2(127, N = 983) = 189.85, p < .01, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03). As shown in Figure 3, Grade 7 academic achievement scores were unexpectedly positively predictive of Grade 8 internalizing problems for boys but not for girls.

Figure 2. Covariances and path coefficients that were estimated in the model with mediating variables.

Average family income and race/ethnicity (represented by two dummy variables) were entered into the model as a covariates.

Figure 3. Path model of mediation between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms.

Numbers on significant paths are unstandardized estimates with standard errors in parentheses. The dotted line is a significant (p < .05) path for boys but a non-significant path for girls. Where separate estimates are shown by gender, estimates for boys are in bold and estimates for girls are in italics. Significant covariances among variables at Grades 4/5 and those among the residuals of the variables at Grades 6/7 are omitted. Fit statistics are CFI = .98, and RMSEA = .03. * p < .05, ** p < .01

For simplicity of presentation, the statistically significant paths in this final partially constrained model are shown in Figure 3, but significant covariances are not shown. Parent-child conflict was the only significant mediator in the predictive association from externalizing behaviors to internalizing symptoms across the transition from late childhood to early adolescence (unstandardized indirect effect = .02, 95% CI: .002, .03; standardized estimate = .01 for both boys and girls). The indirect path through academic achievement was not significant for girls, but it was significant for boys (unstandardized indirect effect = −.03; 95% CI: −.06, −.01; standardized estimate = −.02). The significant indirect path through academic achievement for boys was not as hypothesized because while childhood externalizing behaviors predicted poor academic achievement (β = −.15), this in turn predicted fewer internalizing symptoms (β = .15). Considering that the zero-order correlations between academic achievement and internalizing symptoms were generally non-significant for boys and that there was a positive association between academic achievement at Grade 4 and internalizing symptoms at Grade 8, the unexpected result was considered to be consistent with the pattern of zero-order correlations. A re-analysis of the data using an alternative measure of academic achievement in the data set, namely, teacher reported academic competence, resulted in a similar pattern of association with internalizing problems, attesting to the robustness of the finding. For girls, academic achievement did not predict internalizing symptoms significantly. However, the zero-order correlations between academic achievement and internalizing symptoms showed that they were significantly associated with each other within and across time points but with decreasing magnitude by Grade 8. Social competence was not found to be a significant mediator for either the externalizing to internalizing path or the internalizing to externalizing path. However, externalizing problems at Grades 4/5 did predict less social competence at Grades 6/7 (β = −.09 for boys; β = −.07 for girls).

Parent-child conflict and academic achievement partially accounted for some of the stability of internalizing symptoms and externalizing behaviors, respectively. Parent-child conflict uniquely contributed to the stability of internalizing symptoms as it was predicted by late childhood internalizing problems (β = .10 for boys; β = .11 for girls) and, in turn, predicted more internalizing symptoms in early adolescence (β = .09 for boys; β = .07 for girls; unstandardized indirect effect = .01; 95% CI: .0002, .02; standardized estimate = .01 for both boys and girls). Academic achievement uniquely contributed to the stability of externalizing behaviors since childhood externalizing behaviors predicted lower academic achievement (β = −.15 for boys; β = −.14 for girls), which in turn predicted more externalizing behaviors during adolescence (β = −.12 for boys; β = −.14 for girls; unstandardized indirect effect = .02; 95% CI: .01, .03; standardized estimate = .02 for both boys and girls).

Discussion

The first objective of the current study was to test the predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms while controlling for the initial levels of the problems. Results show that for a sample of youth followed from late childhood to early adolescence, externalizing behaviors during childhood predicted later internalizing symptoms, which in turn predicted externalizing behaviors during adolescence. Although the estimates for the standardized paths between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms were small (β < .10), test of these paths were conservative, adjusting for within construct stability. This evidence supports failure theory and cascading effects theories where dysfunction in one area is hypothesized to spread to other areas of development. The second objective was to simultaneously test several mediating variables, namely, social competence, parent-child conflict, and academic achievement. The results support the hypothesis that parent-child conflict was a mediator in the path from externalizing behaviors in late childhood to internalizing symptoms in early adolescence although, again, estimates of effects were small based on a conservative test of mediation. On the other hand, social competence and academic achievement did not emerge as significant mediators. In early adolescence, internalizing symptoms showed higher stability over time in girls than boys. Additionally, academic achievement and parent-child conflict uniquely contributed to the stability of externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms, respectively. Two results were contrary to the hypotheses – low academic achievement did not predict increase in girls’ internalizing symptoms and academic achievement predicted increase in internalizing symptoms for boys.

Across childhood and adolescence, longitudinal evidence is available to support the predictive associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms. The results of the current study are consistent with this general finding. We found significant cross-construct paths across certain time spans but not others. Within a period of one to two years, externalizing behaviors were related to increases in internalizing symptoms and vice versa. The direction of effects and the developmental timing of these pathways may be associated with the earlier onset and higher prevalence of externalizing behaviors during childhood and the later onset and higher prevalence of internalizing symptoms during adolescence (Keenan et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2005; Lewinsohn & Hops, 1993). Through cascading effects, disruptive and aggressive behaviors during childhood become associated with a range of psychosocial impairment over time and also put individuals at risk of internalizing symptoms by adolescence. Such a mechanism may account for the saliency of the externalizing behaviors to internalizing symptoms pathway during this period. During adolescence, internalizing symptoms tend to become more stable and serious (Hammen & Rudolph, 2003). This increased severity in emotional dysregulation, while affecting other areas of functioning, may also be associated with behavioral dysregulation and acting-out behaviors (Selby, Anesti, & Joiner, 2008). Hence, the internalizing symptoms to externalizing behaviors pathway may emerge most commonly during adolescence.

Parent-child conflict

The current study is the first to investigate the role of parent-child conflict as a mediator between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms. We identified a robust indirect effect of externalizing behaviors on internalizing symptoms through parent-child conflict. This is consistent with studies showing that children with externalizing behaviors experience relatively higher levels of parent-child conflict (Campbell et al., 2010; R. Chen & Simons-Morton, 2009) and that poor quality parent-child relationship increases vulnerability for adolescent depression (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004; Stice et al., 2004). Parents are more likely to encounter parenting challenges and conflicts with children who exhibit externalizing behaviors such as non-compliant and non-cooperative behaviors in response to parental directions and family routines (McMahon & Forehand, 2003). Their children’s impulsive and aggressive tendencies may also make problem-solving and negotiation difficult, thereby increasing emotional stress and conflicts for both parties (Patterson et al., 1998). As a result of more negative interactions, the parent-child relationship is likely to deteriorate and become negatively focused, resulting in lower self-worth and higher internalizing symptoms for the youth (McLeod et al., 2007). Stress in parent-child relationships may also diminish parents’ emotional support of their children, making them more vulnerable to internalizing problems during an important transition period from childhood to adolescence (McLeod et al., 2007; Stice et al., 2004).

Even though empirical evidence suggests that poor parent-child relationships increase the risk of adolescent externalizing problems (Boots et al., 2011; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004), the predictive longitudinal association from parent-child conflict to externalizing behaviors did not reach significance in our study. It is important to note that bivariate correlations between parent-child conflict and externalizing behaviors were significant, but our multivariate models which controlled for the contributions of social competence, academic achievement, and early externalizing problems did not yield an association between these two variables. Prior studies that found significant predictive associations from parent-child conflict to externalizing behaviors had not controlled for academic achievement (Boots et al., 2011; Klahr et al., 2011; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004). Results of the current study attest to the strong associations between academic achievement and externalizing behaviors, in both directions.

The pattern of associations also highlights parent-child conflict as a mediator of the longitudinal association between early and later internalizing symptoms such that childhood internalizing symptoms increases parent-child conflicts, which in turn uniquely contributes to the stability of internalizing problems into adolescence. Internalizing symptoms which are associated with dysfunctional problem solving, coping, and emotional regulation may affect social functioning and result in conflicts with parents (Hamilton et al., 1997; Kaslow et al., 1994). During negative interactions between parents and children, parental hostility and criticism, as well as reduced positive regard for the child are common (Hamilton et al., 1997). Such negativity can undermine children’s self-esteem and adversely affect their self-schemas and sense of efficacy, thus resulting in the stability of their internalizing symptoms (McLeod et al., 2007, Stice et al., 2004). This conceptualization is consistent with the literature on the risk factors for depression. These factors include negative family environments, high levels of conflict, and low parental support (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Marmorstein & Iacono, 2004; Stice et al., 2004).

Social competence

Social competence was not a significant mediator between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms, consistent with two other studies (Bornstein et al., 2010; Burt et al., 2008) but not with another (Obradović & Hipwell, 2010). In spite of this, low social competence was predicted by childhood externalizing behaviors, lending support to the conception that externalizing behaviors interfere with social development and interpersonal relations (Campbell et al., 2010; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Kiesner, 2002; Renouf & Kovacs, 1997; Stice et al., 2004). However, in contrast to some other findings (Boots et al., 2011; Bornstein et al., 2010; Burt et al., 2008; Cole et al., 1996; Sørlie, Hagen, & Ogden, 2008), social competence did not predict externalizing behaviors during adolescence, after controlling for the contribution of academic achievement. Also consistent with the literature, social competence was not as consistently associated with internalizing symptoms (Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Mesman et al., 2001) as it was with externalizing behaviors (Campbell et al., 2010; Capaldi & Stoolmiller, 1999; Kiesner, 2002; Stice et al., 2004. Poor interpersonal skills did not appear to contribute to the emergence of internalizing symptoms in the current study. It is possible that the adverse social and interpersonal consequences that result from poor social competence are more directly predictive of internalizing symptoms than poor social competence per se. For example, peer rejection has often been found to be a significant mediator in the relationship between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms (Gooren et al., 2011; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005; Van Lier & Koot, 2010). It is also possible that parent ratings of social competence during adolescence may not accurately reflect adolescents’ social adjustment since parents do not always have opportunities to observe their adolescents’ social interactions with peers and other adults across multiple settings.

Academic achievement

The current study did not find that academic achievement was a significant mediator in the longitudinal association between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms during the developmental period from late childhood to early adolescence. Controlling for prior levels of academic achievement, externalizing behaviors predicted low academic achievement for both genders like in other studies (Campbell et al., 2006; X. Chen & Rubin, 1997). However, low academic achievement did not predict more internalizing problems as hypothesized. For girls, academic achievement was not related to later internalizing problems, which is consistent with some studies (Ansary & Luthar, 2009; Cole et al., 1996; Lehtinena et al., 2006) but not others (McCarty et al., 2008; Pomerantz et al., 2002). As discussed previously, the empirical support for the path from low academic achievement to internalizing symptoms is still mixed as reflected in the current study (Moilanen et al., 2010; Ansary & Luthar, 2009). It is possible that the effects of academic achievement on depression is indirect and mediated or moderated by factors such as perceived control (Herman et al., 2008), social status, self-perception (Pelkonen, Marttunen, & Aro, 2003), parental rejection, and conflicting parental relationships (X. Chen et al., 1995). Consequently, the associations between academic achievement and internalizing problems are likely to be complex and involve other psychological mechanisms (Lehtinena et al., 2006).

For boys, academic achievement predicted an increase in internalizing symptoms from sixth and seventh to eighth grade, which is in the opposite direction as hypothesized. In this sample, boys who performed well academically appeared to report more internalizing symptoms in adolescence, controlling for prior levels of internalizing symptoms. Behaviors and attitudes necessary for academic success have been associated with feminine traits (Keyder & Kessels, 2013; Kessels & Steinmayr, 2013). Hence, boys who try hard in school or achieve well may be perceived to lack masculinity and be teased, resulting in low social status and poor self-esteem (Hudley & Graham, 2001; Oyserman, Brickman, Bybee, & Celious, 2006) and putting them at-risk of internalizing symptoms. On the other hand, such negative achievement stereotypes are less likely to affect girls (Hudley & Graham, 2001; Cokley, 2002).

Like social competence, academic achievement was more strongly associated with externalizing than internalizing problems. In fact, academic achievement was a significant mediator in the longitudinal association between childhood and adolescence externalizing behaviors and uniquely added to its stability between childhood and adolescence. Childhood externalizing behaviors contributed to low academic achievement which, in turn, predicted more externalizing behaviors in adolescence.

Implications

Evidence for the mediating role of parent-child relationship is consistent with recent literature demonstrating that evidence-based parent training interventions initially designed to target externalizing behaviors have a positive effect on internalizing symptoms (Chase & Eyberg, 2008; Herman, Borden, Reinke, & Webster-Stratton, 2011). However, these studies investigated treatments for young children between the ages of 2 and 8 years. One study on multisystemic therapy, a family and parent-focused therapy for adolescents with externalizing behaviors, measured both externalizing and internalizing behaviors but found only positive outcomes for externalizing but not internalizing symptoms (Henggeler & Rowland, 1999). Although experimental evidence is presently limited for adolescents, the results of the current study suggest that parent training or family-focused programs effective in alleviating externalizing behaviors and improving the parent-child relationship during late childhood and early adolescence may also have a benefit of reducing risks for later internalizing symptoms.

The significant longitudinal associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms across late childhood to early adolescence suggests that youth with behavioral or emotional difficulties are likely to be at-risk of other co-occurring problems. Such reciprocal effects are likely to exacerbate functioning and development across many domains, particularly parent-child relationships. It has been uncommon for treatment studies to measure both externalizing and internalizing symptoms since treatments are often developed to target either one or the other. This trend, however, appears to be changing as more attention is given to co-occurring problems and the effects of treatments in the presence of other co-occurring psychopathology (Kendall, Brady, & Verduin, 2001). As many treatments focused on improving parent-child relationships are designed for children, there is a need for similar types of treatment that are developmentally appropriate for adolescents. We also recommend that treatment studies assess co-occurring symptomatology in youth and measure outcomes related to both externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms.

The high level of stability of internalizing symptoms among girls from late childhood to adolescence suggests that girls with early internalizing symptoms should be carefully monitored throughout development for signs of escalation or need for intervention. Additionally, the stability in internalizing symptoms was largely accounted for by parent-child conflict, whereas the stability in externalizing symptoms was largely accounted for by academic achievement, suggesting differential foci for intervention to address these issues.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of the current study is the use of longitudinal data to model the predictive associations among the variables over the important developmental period of early adolescence. Temporal sequencing of the variables across these transitional years provides a stronger support for causal reasoning about the directions of effects. The second strength is the simultaneous modeling of mediating variables that allows for the evaluation of each effect after adjusting for the effects of other mediating variables. In addition, autoregressive paths were included to control for the previous levels of the mediating variables and symptoms. Overall, these statistical controls allowed for a conservative evaluation of pathways and provided some evidence of cross-construct effects and mediation. The third strength is that the large sample size was adequate for evaluating the moderating effects of gender. Fourth, the data were reported by multiple informants suggesting that the associations between the symptoms and mediators were robust across reporters, such as the path from teacher-reported externalizing behaviors to youth-reported parent-child conflict and the path from standardized measures of academic achievement to youth-report of internalizing symptoms.

One limitation of the study is that a rigorous analysis to compare across racial/ethnic groups was not possible as this study was based on a community sample that was almost 80% Caucasian. Hence, generalizing the findings to other populations should be done with caution. Another limitation is that externalizing and internalizing measures used are not as well validated as standardized scales such as the Childhood Behavioral Checklist and the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. However, many items are similar to those in standardized scales and they have been used in other studies (Greenberg & Kusche, 1990; Kusche & Greenberg, 1988; Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991), thus providing some validity evidence for the measures. It is also acknowledged that the six-item internalizing measure is a limited measure of internalizing symptoms since it focuses primarily on depressive symptoms and has only one or two items in the scale that measure anxiety. Another limitation with respect to measures is that, even though teachers are reliable reporters of youths’ externalizing behaviors in the earlier grades (Severson, Walker, Hope-Doolittle, Kratochwill, & Gresham, 2007), their observation of externalizing behaviors may be limited by eighth grade due to the widening range of settings in which adolescents may exhibit externalizing behaviors. Regarding the analysis strategy, a three-wave model was chosen to test specific mediation hypotheses in a parsimonious manner but it did not allow for the evaluation of the temporal stability of path coefficients across time. More time points would need to be included to assess if the associations remain significant at other time points during the developmental period under investigation. As the effect sizes of the mediation pathways are small, it may be argued that the contribution of these pathways in predicting externalizing behaviors or internalizing symptoms may not be important. However, given that the mediation pathways were significant after controlling for previous levels of the problems, they do offer unique contribution to the stability of externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms.

Even though many inconsistencies in findings remain about the temporal predictive association between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms, the differential developmental significance of the associations, and gender differences, the results of the current study provided some support for the failure theory and cascading effects through the demonstration of indirect mediation effects. This study is the first to show that parent-child conflict plays a mediating role in the development of co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problems from late childhood to early adolescence. Externalizing behaviors during childhood are likely to be related to an increase in parent-child conflict which, in turn may be related to an increase in internalizing symptoms by adolescence. As research continues to clarify the longitudinal associations between externalizing behaviors and internalizing symptoms in youth and their associations with other social and developmental processes, increasing knowledge in this area will provide a stronger theoretical basis for effective treatments for youth with co-occurring psychopathology. Research on co-occurring problems in youth also fits into the wider literature on comorbidity of disorders and could help to explicate the mechanisms for the complex interactions between the disorders and how these processes impact functioning.

References

- Ansary NS, Luthar SS. Distress and academic achievement among adolescents of affluence: a study of externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors and school performance. Development And Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):319–341. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Loeber R. Untangling Developmental Relations Between Depressed Mood and Delinquency in Male Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(3):247. doi: 10.1023/a:1023225428957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots DP, Wareham J, Weir H. Gendered perspectives on depression and antisocial behaviors: An extension of the failure model in adolescents. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38(1):63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C, Haynes OM. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development & Psychopathology. 2010;22(4):717–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Adolescent Substance Use Outcomes in the Raising Healthy Children Project: A Two-Part Latent Growth Curve Analysis. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):699–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Obradović J, Long JD, Masten AS. The Interplay of Social Competence and Psychopathology Over 20 Years: Testing Transactional and Cascade Models. Child Development. 2008;79(2):359–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD. Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2006;47(8):791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Vandergrift N, Belsky J, Burchinal M. Predictors and sequelae of trajectories of physical aggression in school-age boys and girls. Development & Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):133–150. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: I. Familial factors and general adjustment at Grade 6. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3(3):277–300. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: II. A 2-year follow-up at Grade 8. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4(1):125–144. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Stoolmiller M. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: III. Prediction to young-adult adjustment. Development And Psychopathology. 1999;11(1):59–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron C, Rutter M. Comorbidity in Child Psychopathology: Concepts, Issues and Research Strategies. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1991;32(7):1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Mazza JJ, Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Haggerty KP, Fleming CB. Raising healthy children through enhancing social development in elementary school: Results after 1.5 years. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41(2):143. [Google Scholar]

- Chase RM, Eyberg SM. Clinical presentation and treatment outcome for children with comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(2):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Simons-Morton B. Concurrent changes in conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescents: a developmental person-centered approach. Development And Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):285–307. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH. Relation between academic achievement and social adjustment: Evidence from Chinese children. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(3):518. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rubin KH, Li BS. Depressed mood in Chinese children: relations with school performance and family environment. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(6):938–947. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokley KO. Ethnicity, gender and academic self-concept: A preliminary examination of academic disidentification and implications for psychologists. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2002;8(4):378–388. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.4.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Jacquez FM, Maschman TL. Social Origins of Depressive Cognitions: A Longitudinal Study of Self-Perceived Competence in Children. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2001;25(4):377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LA, Seroczynski AD, Fier J. Children's over- and underestimation of academic competence: a longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development. 1999;70(2):459–473. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B, Truglio R. Modeling causal relations between academic and social competence and depression: a multitrait-multimethod longitudinal study of children. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(2):258–270. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM. A Competency-based Model of Child Depression: A Longitudinal Study of Peer, Parent, Teacher, and Self-evaluations. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1997;38(5):505–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Gresham FM, Kern L, Barreras RB, Thornton S, Crews SD. Social Skills Training for Secondary Students With Emotional and/or Behavioral Disorders: A Review and Analysis of the Meta-Analytic Literature. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16(3):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Dart E, Collins T, Restori A, Daikos C, Delport J. Preliminary Study of the Confined, Collateral, and Combined Effects of Reading and Behavioral Interventions: Evidence for a Transactional Relationship. Behavioral Disorders. 2012;38(1):38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Archives Of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CTB. Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills. 4th ed. Monterey, California: Macmillan/McGraw-Hill Company; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Henrich CC. Trajectories of Pure and Co-Occurring Internalizing and Externalizing Problems From Age 2 to Age 12: Findings From the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(5):1159–1175. doi: 10.1037/a0020659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooren EMJC, Van Lier PAC, Stegge H, Terwogt MM, Koot HM. The Development of Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms in Early Elementary School Children: The Role of Peer Rejection. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(2):245–253. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Kusche CA. Manual for Seattle Personality Scale for Children (Revised) Seattle: University of Washington; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty KP, Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Harachi TW, Abbott RD. Raising healthy children: examining the impact of promoting healthy driving behavior within a social development intervention. Prevention Science: The Official Journal Of The Society For Prevention Research. 2006;7(3):257–267. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton EB, Asarnow JR, Tompson MC. Social, academic, and behavioral competence of depressed children: Relationship to diagnostic status and family interaction style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1997;26(1):77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph KD. Childhood mood disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 233–278. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Rowland MD. Home-Based Multisystemic Therapy as an Alternative to the Hospitalization of Youths in. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(11):1331. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199911000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Borden LA, Reinke WM, Webster-Stratton C. The impact of the incredible years parent, child, and teacher training programs on children's co-occurring internalizing symptoms. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0025228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Lambert SF, Reinke WM, Ialongo NS. Low academic competence in first grade as a risk factor for depressive cognitions and symptoms in middle school. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(3):400–410. doi: 10.1037/a0012654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyder A, Kessels U. Is school feminine? Implicit gender stereotyping of school as a predictor of academic achievement. Sex Roles. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Hishinuma ES, McArdle JT, Chang JY. Potential Causal Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Academic Achievement in the Hawaiian High Schools Health Survey Using Contemporary Longitudinal Latent Variable Change Models. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(5):1327–1342. doi: 10.1037/a0026978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- Hudley C, Graham S. Stereotypes of achievement striving among early adolescents. Social Psychology of Education. 2001;5(2):201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Kohl GO, McMahon RJ, Lengua L. Conduct Problems, Depressive Symptomatology and Their Co-Occurring Presentation in Childhood as Predictors of Adjustment in Early Adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(5):602–620. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Deering CG, Racusin GR. Depressed children and their families. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(1):39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Brady EU, Verduin TL. Comorbidity in Childhood Anxiety Disorders and Treatment Outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(7):787. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels U, Steinmayr R. Macho-man in school: Toward the role of gender role self-concepts and help seeking in school performance. Learning & Individual Differences. 2013;23:234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives Of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J. Depressive Symptoms in Early Adolescence: Their Relations with Classroom Problem Behavior and Peer Status. Journal of Research on Adolescence (Blackwell Publishing Limited) 2002;12(4):463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, Rueter MA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA. The relationship between parent-child conflict and adolescent antisocial behavior: confirming shared environmental mediation. Journal Of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(5):683–694. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9505-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]