Abstract

Aβ42 peptides associate into soluble oligomers and protofibrils in the process of forming the amyloid fibrils associated with Alzheimer’s disease. The oligomers have been reported to be more toxic to neurons than fibrils, and have been targeted by a wide range of small molecule and peptide inhibitors. With single touch atomic force microscopy (AFM), we show that monomeric Aβ42 forms two distinct types of oligomers, low molecular weight (MW) oligomers with heights of 1–2 nm and high MW oligomers with heights of 3–5 nm. In both cases, the oligomers are disc-shaped with diameters of ∼10–15 nm. The similar diameters suggest that the low MW species stack to form the high MW oligomers. The ability of Aβ42 inhibitors to interact with these oligomers is probed using atomic force microscopy and NMR spectroscopy. We show that curcumin and resveratrol bind to the N-terminus (residues 5–20) of Aβ42 monomers and cap the height of the oligomers that are formed at 1–2 nm. A second class of inhibitors, which includes sulindac sulfide and indomethacin, exhibit very weak interactions across the Aβ42 sequence and do not block the formation of the high MW oligomers. The correlation between N-terminal interactions and capping of the height of the Aβ oligomers provides insights into the mechanism of inhibition and the pathway of Aβ aggregation.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques in the brain. These plaques are composed mostly of Aβ peptides generated by proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by two proteases, β- and γ-secretase.1,2 The primary cleavage product is an Aβ peptide with a length of 40 residues (Aβ40). However, proteolysis is not highly specific and ∼10% of the cleavage products of APP are peptides with two additional amino acids at the C-terminus (Aβ42). The Aβ42 peptide is more toxic to neuronal cells than Aβ40,3 and post-mortem analysis reveals Aβ42 to be the principal component of amyloid plaques in AD patients.4 Several familial mutations in the APP gene associated with early onset AD have been found to increase the ratio of Aβ42-to-Aβ40.5 These observations have led to the conclusion that Aβ42 plays a pivotal role in the progression of AD.

One of the challenges in designing Aβ42 inhibitors and understanding their ability to block Aβ toxicity has been that the Aβ42 monomers rapidly associate to form low molecular weight (MW) oligomers which can subsequently combine to form higher MW oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils. This association results in a complex mixture of Aβ aggregates whose structures change over time. Although early findings in the amyloid field implicated the fibrillar deposits in the brains of AD patients as the cause of neuronal toxicity, more recent results have suggested that small soluble oligomers are the primary toxic species.6−8

There is rich literature on the pathways for Aβ association and the structures of possible intermediates en route to forming fibrils.6,7,9,10 There is general agreement that monomeric Aβ produced by γ-secretase cleavage is not toxic.11 There is much less agreement on the pathway(s) of oligomer formation, and the size and composition of the oligomers. In in vitro studies, the monomer concentration and solution temperature are two critical parameters controlling Aβ oligomer formation. The Aβ42 peptide is monomeric up to a concentration of ∼3 μM at 25 °C,12 and low temperature (4 °C) can be used to stabilize the monomer at higher concentrations.13,14 Oligomers readily form at higher concentrations and temperature; the kinetics of oligomer and fibril formation are strongly dependent on the concentration and temperature used.15,16 The temperature dependence of the association suggests that monomeric Aβ42 first associates through hydrophobic interactions to form soluble oligomers.

Although a host of other factors influence the aggregation of the Aβ peptides, including salt concentration, pH, and the presence of metal ions,17 there appear to be two general size classifications of soluble oligomers, low and high MW. Low MW oligomers of Aβ42 have been observed at ∼20 kDa by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis.6,18,19 This MW roughly corresponds to a tetramer. Ion mobility measurements obtained using mass spectrometry show that the low MW forms are predominantly tetramers with smaller amounts of dimers and hexamers.20 On the basis of photochemical cross-linking, Bitan, Teplow, and co-workers21 concluded that the stable Aβ42 oligomers isolated by size-exclusion chromatography are predominantly pentamers and hexamers. Together, these results show that while there is a small range of low MW oligomer sizes, the low MW oligomers do not have a defined composition or structure.

High MW oligomers are a second general size classification of soluble oligomers. The most commonly observed high MW oligomer has a molecular mass of ∼56 kDa, corresponding to a dodecamer. The high MW oligomers appear to be more toxic in vitro and in vivo compared to Aβ42 monomers, low MW oligomers, and fibrils,9,22−24 although Aβ dimers isolated from the AD brains were shown to impair synaptic plasticity.25 For example, Lesne et al.9 found that an oligomeric species, which they term Aβ*56 on the basis of an apparent MW of 56 kDa, can impair memory in transgenic mice expressing human APP. Barghorn et al.24 also describe the production of a ∼60 kDa Aβ42 oligomer that binds to dendritic processes of neurons in cell culture and blocks long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal slices. Ion mobility studies with mass spectrometry showed that dodecamers are the predominant higher order oligomeric form of Aβ42.20 The absence of an 18-mer species in these studies suggested that the hexamers (or other small oligomers) do not associate with the dodecamer. Rather, it was proposed that the dodecamer rearranges and forms fibrils.

Many Aβ inhibitors prevent fibril formation or disrupt mature fibrils,26−32 and potentially give rise to toxic Aβ species.33 Aβ42 inhibitors have been shown by NMR to interact with the N-terminus (residues 1–20) and C-terminus (residues 31–42) of the peptide. Both the N- and C-termini influence the transition of Aβ monomers to fibrils. The hydrophobic C-terminus of Aβ42 has long been recognized as important in driving fibril formation.34 Structural models place the C-terminus at the core of Aβ4035 and Aβ4236 fibrils, and inhibitors have been designed to disrupt the packing within the C-terminus.36,37 Although the N-terminus is unstructured in fibril models and believed to not be important in the final folded fibril,38,39 several studies suggest that it has a role in fibril formation.40−43

In this study, we combine high resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) and NMR to characterize the size of the oligomers and their interaction with several different types of Aβ42 inhibitors. Due to differences in oligomer height, AFM allows us to distinguish low and high MW oligomers. We have previously shown that single touch AFM provides a low force method to image oligomers with high resolution under hydrated conditions.44 NMR spectroscopy provides a way to assess the sites of Aβ–inhibitor interaction. Two-dimensional 1H–15N correlation experiments allow one to monitor the specific residues that contribute to inhibitor binding using previous backbone assignments for Aβ42.13,45 Our current studies focus on the incubation of Aβ42 at concentrations of ∼50–200 μM, above the critical concentration for Aβ42 aggregation.46

We investigate two classes of inhibitors that interact predominantly either with the N-terminus (and central KLVFF region) of the Aβ peptide or with the hydrophobic C-terminus. Curcumin, the yellow pigment in turmeric, has been studied extensively as an inhibitor of Aβ42 fibril formation (for a review, see ref (47)), and falls into the class of N-terminal inhibitors. Ono et al.48 found that curcumin can block fibril formation and lower toxicity. NMR studies show that interactions predominantly occur at the N-terminus of the peptide. There are many polyphenolic compounds that appear to behave like curcumin in terms of binding to Aβ42 and inhibiting fibril formation. We also target resveratrol, another common natural product found in wine, which inhibits Aβ42 fibril formation and cytotoxicity but not Aβ42 oligomerization.49

The second class of inhibitors we target are small molecule nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that have been developed to treat acute or chronic inflammation, but have also been studied extensively as therapeutics for AD. We present AFM and NMR data on two NSAIDs, sulindac sulfide and indomethacin, which have similar structures and have been reported to bind to Aβ42 and inhibit fibril formation.37,50 Importantly, Richter et al.37 found that the addition of sulindac sulfide in a 1:3 molar ratio of Aβ42 to inhibitor resulted in changes in the chemical shifts of residues in the Aβ42 C-terminus (Ile32, Leu34, Met35, and Val39) using NMR spectroscopy.

Curcumin and resveratrol are natural products that are widely consumed, while sulindac sulfide and indomethacin are representative of a class of pharmaceuticals (NSAIDs) commonly prescribed for chronic inflammation. Our studies directly compare these two types of Aβ inhibitors and address whether the location of inhibitor binding influences the structure or formation of the different size oligomers.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Oligomers

Aβ42 peptides were synthesized using tBOC-chemistry on an ABI 430A solid-phase peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using linear water–acetonitrile gradients containing 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. Based on analytical reverse phase HPLC, the purity of the peptides was 90–95%. The mass of the purified peptide was measured using matrix-assisted laser desorption or electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, and was consistent with the calculated mass for the peptide.

Monomeric Aβ42 was prepared by dissolving purified peptide in 100 mM NaOH, diluting into low salt buffer (10 mM phosphate, 10 mM NaCl) at low temperature (4 °C), and adjusting the pH to 7.4. The Aβ solutions were then filtered two times with 0.2 μm cellulose acetate filters to remove insoluble aggregates that can nucleate and influence aggregation. Unless otherwise indicated, the final concentration of Aβ42 monomer was adjusted to 200 μM for the studies described below. To initiate Aβ aggregation, the solutions of monomeric peptide at 4 °C were placed in a 37 °C incubator and slowly shaken. For AFM measurements and fluorescence measurements, aliquots of the peptide solution were removed at time points between 0 and 48 h and diluted to <20 μM immediately before the measurement. In parallel with this study, we have undertaken a detailed characterization of the influence of concentration and temperature on Aβ42 aggregation (Fu et al., unpublished results). The concentration (200 μM) and temperature (37 °C) used here are favorable for the conversion of monomeric Aβ to oligomers prior to fibril formation through the mechanism of nucleated conformational conversion.

Small molecule inhibitors were cosolubilized with Aβ42 in selected experiments by mixing concentrated stock solutions of inhibitors and Aβ42 in 100 mM NaOH, and then diluting the mixture into low salt buffer (10 mM phosphate, 10 mM NaCl) at low temperature (4 °C) and adjusting the pH to 7.4. All experiments reported here used a molar ratio of Aβ42:inhibitor of 1:1. Since curcumin is unstable in aqueous solution and in the presence of light,51 the solutions were kept in the dark, and absorption spectra were obtained to estimate the amount of degradation (Supporting Information Figure S2). Over the 10 h time course of the AFM measurements, we lose ∼50% of the initial curcumin in these samples, and consequently we cannot rule out that curcumin degradation products contribute to the observed capping of low MW oligomers.

For NMR experiments, 15N- labeled Aβ42 peptide (rPeptide, Bogart, GA) was dissolved in 100 mM NaOH at a concentration of 2.2 mM, then diluted in low salt buffer containing 10% D2O to a 200 μM concentration. The concentrations of the peptide stock solutions were determined by absorbance at 275 nm using the extinction coefficient for tyrosine of 1420 M–1 cm–1. The concentrations of the inhibitor stock solutions were determined by absorbance and/or NMR spectroscopy. The stock solutions in NaOH were made immediately prior to use.

Atomic Force Microscopy

AFM images were obtained using a MultiMode microscope (Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) with a custom-built controller (LifeAFM, Port Jefferson, NY) that allows one low force contact (30–50 piconewtons) of the AFM tip to the sample surface per pixel. The single touch approach is rapid and allows one to image a 1 μm × 1 μm field in ∼4 min. The AFM operation is embedded in a computer program that provides subangstrom linear control of cantilever base and tip position, including programmed contact and programmed separation of the tip by a magnetic force ramp. Supersharp silicon probes with a tip width of typically 3–5 nm (at a height of 2 nm) were modified for magnetic retraction by attachment of samarium cobalt particles. Figure S3 presents an image of DNA showing the helical repeat of 3.4 nm, which provides an estimate of the resolution in the single touch AFM experiments and shows how the tip width of the AFM probe influences the observed width of the sample, but not the height. The oligomer diameters that are reported account for the width of the AFM probe.18,44 Samples for AFM were diluted to a concentration of 0.5 μM deposited onto freshly cleaved ruby mica (S & J Trading, Glen Oaks, NY) and imaged under hydrated conditions. The AFM instrument used in our studies does not have temperature control, and in the case of our initial t = 0 h time point, the Aβ42 oligomers rapidly form from monomeric Aβ as the sample temperature increases from 4 °C as the sample is layered on the mica surface for measurements. The total time for layering the samples and acquiring images is ∼15 min. At least five regions of the mica surface were examined to ensure that similar structures existed throughout the sample. Histograms were compiled using Microsoft Excel from nonoverlapping particles in multiple fields.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence experiments were performed using a Horiba Jobin Yvon Fluorolog FL3-22 spectrofluorimeter. At each time point, aliquots were taken and mixed with 30 μM thioflavin T to produce mixtures with a peptide-to-thioflavin T ratio of 1:20. Thioflavin T fluorescence emission spectra were obtained from 475 to 550 nm using an excitation wavelength of 461 nm.

Solution NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectra of Aβ42 oligomers were obtained at 700 MHz on a Bruker AVANCE spectrometer with a TXI probe. The temperature was maintained at 4 °C to reduce peptide fibrillization. NMR measurements were made with standard 5 mm NMR tubes containing a Teflon tube liner (Norell, Inc.). The Teflon liner prevents glass catalyzed Aβ aggregation. 1H–15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra were acquired using pulse field gradient water suppression and GARP decoupling with the transmitter offset placed at the water frequency. The number of points acquired in the direct dimension (1H) was 2048, and the number of increments in the indirect dimension (15N) was 128. The data in the indirect dimension were linear predicted to 256 points before Fourier transformation for a spectral resolution of 1.38 Hz/point in the 1H dimension and 8.82 Hz/point in the 15N dimension. Assignments were taken from refs (13) and (45).

Results

Stacking of Aβ42 Oligomers

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) are used to visualize the formation of oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils from monomeric Aβ peptides. AFM (Figure 1A,B) is most often used for imaging oligomers, while TEM is used primarily for imaging protofibrils and fibrils. Monomeric Aβ42 is not generally observed by either method. However, there is general agreement in the literature that low temperature can be used to stabilize monomeric Aβ.13,14,52 In the Supporting Information (Figure S4) and Materials and Methods, we describe the preparation of monomeric Aβ42 by disaggregating in NaOH, titrating to pH 7.4, and diluting into buffer at 4 °C. The solutions are then filtered at 4 °C prior to use in order to remove aggregated Aβ that can seed fibril formation. Diffusion measurements are used to show that the Aβ42 peptide is monomeric at 4 °C and converts to a low MW oligomeric species with a size corresponding to a hexamer after incubation at 20 °C (Figure S4).

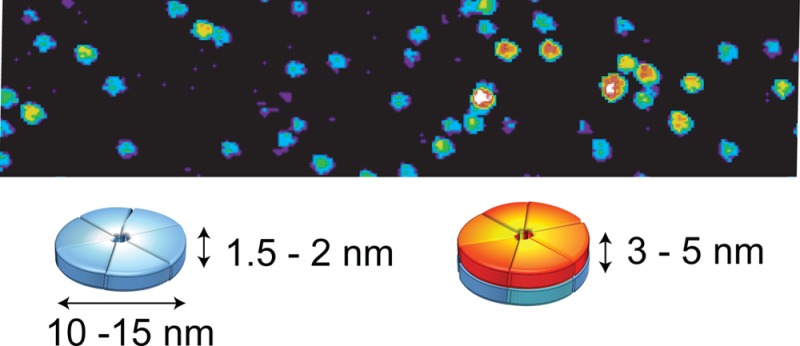

Figure 1.

Single-touch AFM of Aβ42 oligomers. The AFM image in (A) was obtained of oligomers starting with monomeric Aβ42 stabilized at low temperature (4 °C) for 72 h in 10 mM phosphate, 10 mM NaCl buffer prior to AFM measurements. The peptides are largely monomeric prior to warming the solution as it is layered on the mica grid for imaging. Warming to room temperature causes a rapid conversion to Aβ42 oligomers with heights of ∼1.5–2.5 nm. (B) At higher temperature (37 °C, 6 h), the number of 3–5 nm high oligomers rapidly increases. The height measurements by AFM are accurate to within ∼0.1 nm.44 The scale bars are 100 nm. (C) Cartoon of Aβ42 low and high MW oligomers illustrating that stacking doubles the height of the oligomers without changing their diameter. NMR diffusion measurements were used to establish the presence of monomeric Aβ42 at low temperature (Figure S4). Mass spectrometry20 and cross-linking21 suggest that the low MW oligomers correspond to tetramers, pentamers, and hexamers. On native gels, we observe a band at ∼20 kDa, corresponding to the MW between a tetramer and pentamer. Diffusion measurements reveal the formation of oligomers with a diffusion coefficient close to that of a 26 kDa globular protein (Figure S4).

Figure 1A presents an AFM image of low MW oligomers. These oligomers rapidly form from Aβ42 monomers after increasing the temperature or increasing the Aβ concentration. One of the advantages of AFM is the ability to image the size and shape of the Aβ oligomers during the aggregation process. Figure 1A shows that monomeric Aβ42 at 4 °C, when warmed to room temperature, yields a relatively homogeneous field of oligomers with heights of ∼1.0–2.0 nm. Incubation of Aβ42 at ∼15 °C or higher allows formation of oligomers, protofibrils and finally mature fibrils. Figure 1B shows that after 6 h of incubation at 37 °C the oligomers predominantly have heights of 3–5 nm.

One can follow the transition of the short (low MW) oligomers to tall (high MW oligomers) by measuring the oligomer heights as a function of incubation time (Figure 2A). There is a gradual shift of the low MW oligomers to high MW oligomers over an 8 h incubation period at 37 °C. Figure 2B summarizes this shift in height by counting oligomers in the range of 1.0–2.5 nm and in the range of 3–5 nm.

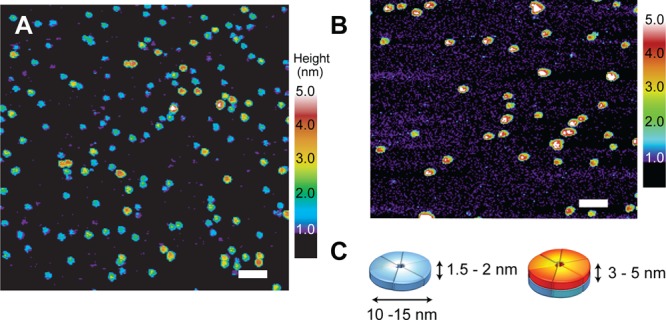

Figure 2.

Time course of oligomer and fibril formation. (A) Histograms of Aβ42 oligomer height after 0–8 h of incubation. The heights of the Aβ42 oligomers were obtained by AFM at 37 °C in low salt buffer. (B) Conversion of short to tall Aβ42 oligomers over 8 h of incubation based on heights measured by AFM. The plot shows the number of oligomers with heights between 1.0–2.5 nm (black squares) and between 3–5 nm (gray circles). The analysis in (B) was based on at least three independent data sets for each time point. The AFM measurements only yield the relative numbers of each oligomer type as a function of the incubation time. The total number of oligomers decreases with time. However, here we normalize the total number of oligomers to 100 at each incubation time point. The change in thioflavin T fluorescence over a similar time scale is shown on the same plot (blue diamonds, solid line).

The time course for oligomer heights is plotted on the same graph as the change in thioflavin T fluorescence. Thioflavin T has been widely used to characterize the time dependence of fibril formation. Thioflavin T exhibits an increase in fluorescence intensity at 490 nm when bound to Aβ42 fibrils, but not when bound to monomeric Aβ.53 In Figure 2B (blue trace), we show that when incubated with Aβ42 the thioflavin T fluorescence exhibits a lag phase typical of nucleation dependent fibril formation. A sharp increase in fluorescence is observed after 6–7 h. The time course of fibril formation reflected by the thioflavin T fluorescence is largely consistent with the TEM images showing oligomers and protofibrils prior to 6 h and protofibrils and fibrils after 6 h (Figure S5). These images are consistent with the AFM studies showing that the high MW oligomers are formed prior to fibril formation. Similar experiments were undertaken with Aβ42 originally solubilized in DMSO rather than NaOH (Figure S1). The DMSO leads to a delay in the Aβ aggregation kinetics, but the transition of low to high MW oligomers is still observed prior to fibril formation.

The AFM images of Aβ42 oligomers in Figure 1A and B reveal a mixture of two distinct populations characterized by their heights. The height measurement in AFM is extremely accurate (±0.1 nm) and the low force, single touch approach reduces distortion of the height during the imaging process.44 Although the heights of the Aβ42 oligomers increase as a function of time, the diameters remain roughly the same, between ∼10 and 15 nm (Figure 1A, B). The diameters of the oligomers observed in the AFM images are sensitive to the width of the tip of the AFM probe (see Figure S3).44 With relatively broad tips, the apparent oligomer widths can be on the order of 25 nm. However, even in these cases, the low and high MW oligomers have similar diameters. The observation of two populations that differ in height without a large change in diameter argues that the oligomers are disc-shaped rather than spherical. The disc shape, along with the time-dependent increase in height, suggests that the low MW oligomers stack to form the high MW oligomers, and that this stacking precedes fibril formation.

Small Molecule Inhibitors Cap Oligomers of Aβ42

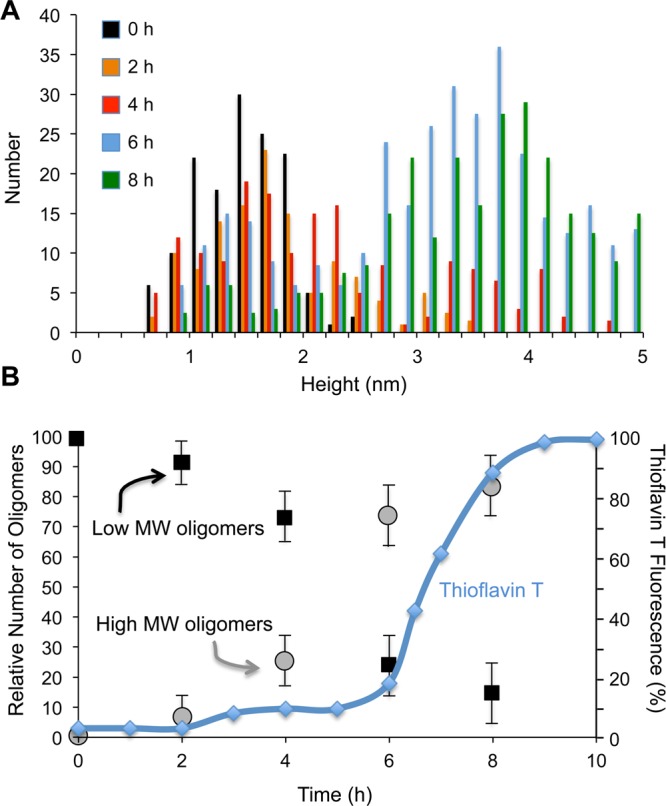

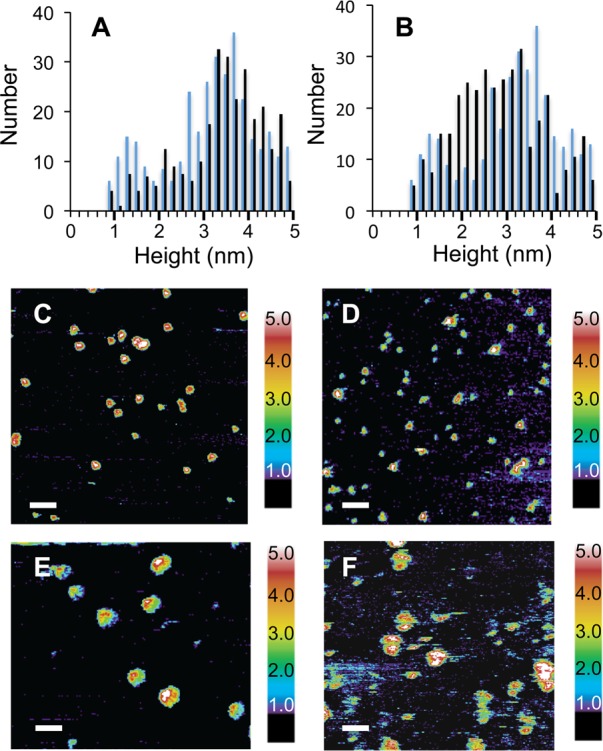

The influence of Aβ42 inhibitors on the distribution of the low and high MW oligomers was assessed by AFM. We selected several inhibitors that bind to Aβ and either slow or prevent fibril formation.33 Figure 3A and B compares the distribution of heights of Aβ42 after 6 h of incubation with and without curcumin or resveratrol added at a 1:1 molar ratio of Aβ monomer-to-inhibitor. The 6 h time point corresponds to the end of the lag phase observed by thioflavin T fluorescence. At this time point, which is prior to the rapid appearance of fibrils in TEM images, there is a large increase in the high MW oligomers and protofibrils relative to the low MW oligomers. When incubated with either curcumin or resveratrol at a 1:1 molar ratio, the heights of the Aβ42 oligomers are capped at ∼2.5 nm. Representative AFM images of inhibited samples after 6 h of incubation are shown in Figure 3C and D. It is well-known that curcumin is unstable in aqueous solution, and degrades to vanillin, ferulic acid, feruloyl methane, and trans-6-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-2,4-dioxo-5-hexenal.51 While the stability of curcumin is enhanced by binding to Aβ42 (Figure S2), there is still significant degradation over the time course of these experiments and consequently the degradation products may contribute to capping of the low MW oligomers.

Figure 3.

Capping of oligomer heights by inhibitors. (A) Capping of Aβ42 oligomer heights by curcumin. Histograms are shown of oligomer heights obtained from AFM images after 6 h of incubation of Aβ42 either with (black bars) or without (blue bars) curcumin. The temperature was maintained at 37 °C and the molar ratio of curcumin-to-Aβ42 was 1:1. (B) Capping of Aβ42 oligomer heights by resveratrol. Histograms are shown of oligomer heights after 6 h of incubation of Aβ42 either with (black bars) or without (blue bars) resveratrol at 37 °C and a molar ratio of resveratrol-to-Aβ42 of 1:1. (C–F) AFM images of Aβ42 with curcumin (C,E) or resveratrol (D,F) after incubation for 6 h. Scale bars are 100 nm in (C,D) and 50 nm in (E,F).

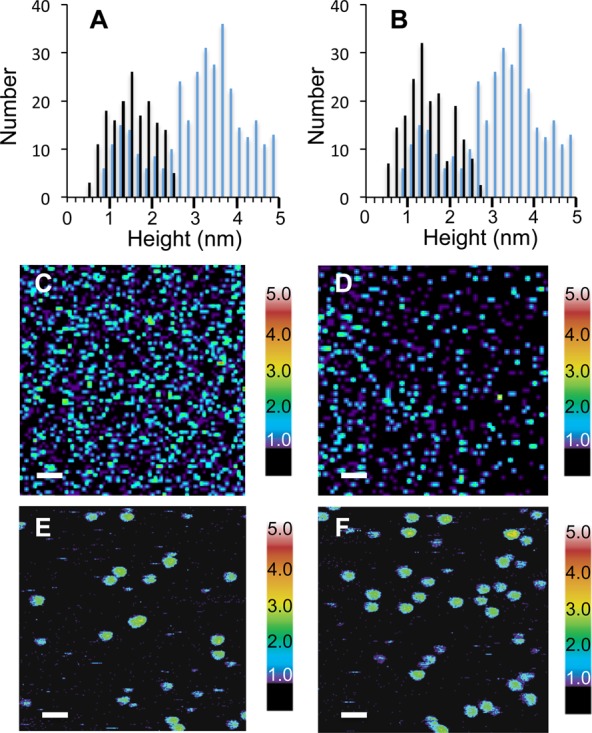

In contrast to curcumin and resveratrol, we also characterized Aβ inhibitors that do not cap the oligomer height. Figure 4A and B compares the distribution of heights of Aβ42 after 6 h of incubation with and without sulindac sulfide and indomethacin. There is a broad range of heights from ∼1.0–5 nm with a maximum of ∼3–3.5 nm, consistent with the average height corresponding to a high MW oligomer. Representative AFM images are shown in Figure 4C and D. In contrast to curcumin, sulindac sufide has previously been shown to interact with the C-terminus of Aβ42.37

Figure 4.

AFM of Aβ42 with indomethacin and sulindac sulfide. Panels (A) and (B) present histograms of heights observed of Aβ42 incubated for 6 h with (black bars) or without (blue bars) indomethacin and sulindac sulfide, respectively. In contrast to the results with curcumin and resveratrol, these Aβ inhibitors do not cap the height of the Aβ42 oligomers. (C–F) AFM images are shown of Aβ42 with indomethacin (C,E) or sulindac sulfide (D,F) after incubation for 6 h. Scale bars are 100 nm in (C,D) and 50 nm in (E,F).

Capping Inhibitors Have a Common Binding Mode to Aβ42

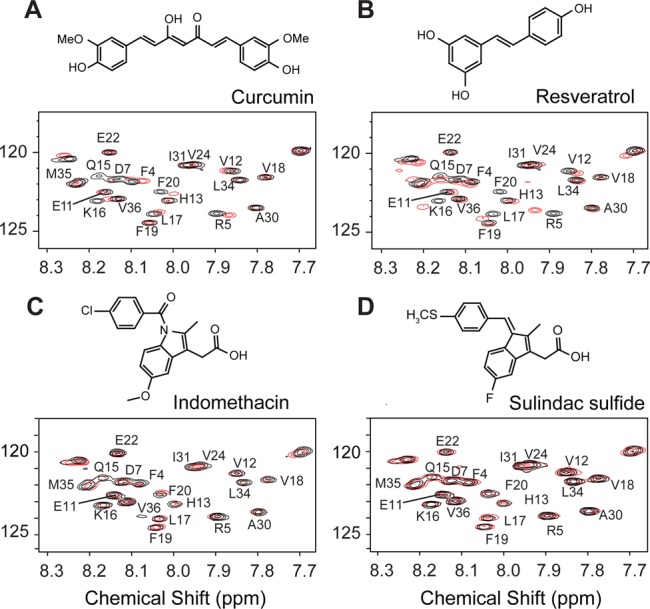

We next evaluated the mechanism by which curcumin and other small molecules bind to Aβ and modulate their oligomerization using 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectroscopy. This two-dimensional NMR experiment yields resonances that correspond to the directly bonded 1H–15N sites in the protein. In these studies, changes in the chemical shifts of the 1H–15N resonances of Aβ42 are expected at those sites where the inhibitor binds to the peptide. The 1H–15N NMR spectra of 15N-labeled Aβ42 are shown in Figure 5 in the absence and presence of curcumin, resveratrol, indomethacin, and sulindac sulfide. The spectrum of Aβ42 with thioflavin T was acquired as a negative control (Figure S6). Thioflavin T is reported to only bind to Aβ42 fibrils and not to monomers or oligomers,54 and has no ability to inhibit fibrillization as compared to the Aβ42 inhibitors.54 In agreement with these observations, thioflavin T does not induce changes in the 1H–15N spectrum of Aβ42, although it is worth noting recent reports on α-synuclein indicating that thioflavin T can interact with the disordered monomer.55

Figure 5.

Solution NMR spectroscopy of Aβ42 oligomers with small molecule inhibitors. 1H–15N HSQC spectra were obtained of Aβ42 alone (black) and after coincubation (red) with curcumin (A), resveratrol (B), indomethacin (C), and sulindac sulfide (D). Molecular structures of the inhibitors are drawn above their corresponding spectra. Only the central portions of the 2D NMR spectrum are shown. Inhibitors were added in a 1:1 molar ratio of inhibitor to Aβ42 (200 μM concentration). Relatively large chemical shift changes are observed with the addition of curcumin and resveratrol. In contrast, there are no appreciable changes in chemical shift with indomethacin and sulindac sulfide (see also Table S1).

The binding of curcumin or resveratrol results in several similar changes in specific 1H–15N chemical shifts of Aβ42. The largest chemical shift changes are observed in residues in the N-terminus and middle region of the Aβ42 sequence, including Phe4, Arg5, Gln15, Lys16, Leu17 and Phe20. The binding occurs predominantly at the positions of polar residues that are found to be surface exposed and accessible to exchange of their NH protons by water (Figure S7). In contrast, the NMR chemical shifts corresponding to the hydrophobic C-terminal residues of Aβ42 are unchanged. The temperature dependence of oligomer formation suggests that hydrophobic (C-terminal) interactions are involved in monomer association, and the absence of changes in the C-terminus upon inhibitor binding agrees with the observation that adding inhibitor to monomeric Aβ does not prevent the formation of low MW oligomers.

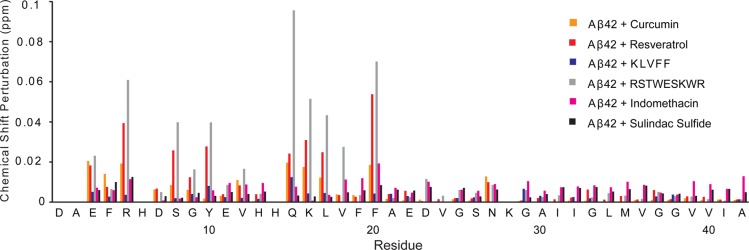

The chemical shift differences along the peptide backbone are shown in Figure 6 for Aβ42 in the presence and absence of curcumin or resveratrol. These plots highlight the similar spectral changes upon binding of these inhibitors, notably at Arg5, Gln15, and Phe20, and the absence of chemical shift perturbations in the C-terminus of the peptide.

Figure 6.

NMR chemical shift changes in Aβ42 upon inhibitor binding. The chemical shift differences are shown between Aβ42 alone and Aβ42 with curcumin (orange), between Aβ42 alone and Aβ42 with resveratrol (red) and with the other inhibitors studied. The largest changes are observed for residues in the hydrophilic N-terminus of the Aβ42 peptide. The RSTWESKWR peptide (gray), which was designed to interact with Aβ42,36 shows large chemical shift changes in the N-terminus and middle region of the peptide. Indomethacin (pink) and sulindac sulfide (black) are γ-secretase modulators that interact with both the C-terminal fragment of the amyloid precursor protein and Aβ42 to reduce neuronal toxicity.37,50,74 The NMR chemical shift changes upon the addition of these inhibitors are minor. No effect of the KLVFF peptide inhibitor (blue) on Aβ chemical shifts was observed. To account for the differences in the 1H and 15N chemical shift ranges, the chemical shift perturbations were calculated as the average chemical shift change75 (Δδ) using the equation Δδ = [{(ΔCSH)2 + (ΔCSN/5)2}/2]1/2. The chemical shifts differences are tabulated in Tables S1–S7. The resolution in the1H dimension is 1.38 Hz/point (∼0.002 ppm/point) and in the 15N dimension is 8.82 Hz/point (∼0.12 ppm/point). The largest chemical shift changes in 1H (0.077 ppm) and 15N (−0.955 ppm) were observed for the I1 inhibitor (Table S1).

The 1H–15N HSQC spectra of the γ-secretase modulators, indomethacin and sulindac sulfide, are presented in Figure 5C and D. In our studies, when indomethacin and sulindac sulfide were incubated with Aβ42 at 1:1 molar ratio, no appreciable shifts were observed in the 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectra. Rather, there were smaller shifts distributed over the length of the peptide (see Figure 6, Supporting Table S1). The difference between our results and the previous studies may be related to the higher concentration used by Richter et al.37 (3:1 molar ratio of sulindac sulfide-to-Aβ42). These inhibitors were not able to cap the oligomers (Figure 3) as found for resveratrol and curcumin (Figure 3) at a 1:1 molar ratio. Nevertheless, in the previous studies, sulindac sulfide exhibits more significant binding than indomethacin, consistent with the larger differences in the height distributions observed by AFM (Figure 4).

Discussion

Stacking of Low MW Aβ Oligomers

The AFM images of two types of oligomers with similar diameters and different heights suggest that stacking of two shorter species may form the taller oligomers. This hypothesis is supported by two observations. First, only the low MW form is found in the presence of specific inhibitors, consistent with the high MW oligomers being formed from the low MW species. Second, we show that the decrease in the number of low MW oligomers as a function of incubation time is correlated with a gain in the number of high MW oligomers.

The idea that the oligomers can stack was previously proposed on the basis of ion mobility measurements using mass spectrometry.20 In this study, the dominant oligomer forms were tetramers, hexamers, and dodecamers. The authors suggested that the addition of a third hexamer to the dodecamer form was energetically unfavorable and that the dodecamer is metastable and rearranges to a nucleating species that rapidly adds monomeric Aβ to form fibrils. In addition, this group has recently shown that the addition of a small molecule Aβ inhibitor (Z-Phe-Ala-diazomethylketone) blocks the formation of Aβ42 dodecamers.56 This peptide derivative has structural similarities to curcumin and to a designed inhibitor peptide (I1, RGTFEGKF-NH2), which was previously shown to stabilize or cap the low MW oligomers.44 Z-Phe-Ala-diazomethylketone and curcumin both contain two 6-membered aromatic groups separated by 7 and 8 bonds, respectively.

More recently, ion mobility spectrometry studies have shown the presence of aggregates that are larger than dodecamers.57 These studies were carried out at higher concentrations (200 μM) than that of Bowers and colleagues (30 μM).20 In a parallel study, we have shown that at 200 μM Aβ42 the low and high MW oligomers are able to laterally associate in addition to their ability to stack (Fu et al., unpublished results). The lateral association of oligomers into protofibrils is directly on the pathway to fibrils through the mechanism of nucleated conformational conversion.

Structural Implications of Aβ Oligomer Stacking

Many of the early models of Aβ oligomers proposed that they were spherical micelles with a hydrophobic core formed by an unstructured C-terminus and a hydrophilic surface formed from the polar N-terminus.46 Since these early proposals, considerable data have revealed that both the monomers and oligomers adopt partial structure. In the case of the Aβ monomer, NOE and chemical shift data show there is residual β-strand structure at Leu17-Ala21 and Ile31-Val36 and turn structures at Asp7-Glu11 and Phe20-Ser26.13 Water accessibility studies show that regions in both N- and C-termini are protected from exchange (Figure S7) and that the C-terminus has less flexibility.58 A recent solution NMR structure of the Aβ40 monomer shows that residues from His13 to Asp23 form a 310 helix, and that both the N- and C-termini pack against the helix due to a clustering of hydrophobic residues.59

The observation that the monomers are partially structured is important for developing models of the low and high MW oligomers, and understanding the transition from oligomers to fibrils. Within the monomers comprising the Aβ oligomers, solid-state NMR studies have shown that a β-hairpin allows intrastrand hydrogen bonding between the β-strand structures at Leu17-Ala21 and Ile31-Val36.18 Studies incorporating intramolecular disulfide linkages have shown that locking the β-hairpin structure in place prevents a transition to β-sheet secondary structure formed by interstrand hydrogen bonding between the LVFFA and the IIGLMV sequences on adjacent peptides.60 The transition to interstrand hydrogen bonding is essential for forming fibrils with cross-β sheet structure.

The model that emerges is one where the oligomers rapidly form through hydrophobic interactions involving the C-terminus. The low MW oligomers appear to have two distinct surfaces, where one surface is able to mediate the association to form the high MW species. This face-to-face interaction explains the lack of 18-mers observed in our AFM studies as well as in the previous mass spectrometry experiments.20 One can speculate that the interacting surface is more hydrophobic. We find that the oligomers associate strongly with the polar mica surface in AFM. In AFM studies using graphite that has a hydrophobic surface, more fibril-like structures are observed, suggesting that the hydrophobic surface destabilizes the oligomers and serves as template for fibril formation.61

As described above, in parallel with the studies described here, we have addressed the ability of the low and high MW oligomers to laterally associate and form protofibrils. The lateral association of the unstructured oligomers can be reversed until they begin to develop the β-sheet structure characteristic of mature fibrils (Fu et al. unpublished results). The stacking of oligomers to generate a hydrophobic core may facilitate the rearrangement of the central hydrophobic LVFFA sequence and C-terminal sequence to form a β-hairpin structure that precedes fibril formation.

Inhibitors That Cap Aβ42 Oligomers Are Associated with N-Terminal Interactions

A large number of Aβ42 inhibitors have been described in the literature, and one of the objectives of this study is to compare how they interact with Aβ42 monomers and oligomers. Comparing the chemical shift changes induced in Aβ42 by our small molecule inhibitors, the largest shifts upon inhibitor binding to Aβ42 involve residues in the N-terminal and central portions of the peptide (Figure 6). Arg5, Ser8, Tyr10, Gln15, Lys16, Leu17, and Phe20 were the most affected residues. Measurements of water accessibility indicate that these residues that interact with Aβ42 inhibitors are also solvent accessible (Figure S7). For example, Phe20 is water accessible and undergoes a large change in chemical shift upon inhibitor binding. In contrast, the adjacent Phe19 is inaccessible to solvent and insensitive to inhibitor binding, arguing that Phe19 and Phe20 have opposite orientations in the folded Aβ42 monomer. Our observations agree with recent computational studies. Zhu et al.62 found that regions of the Aβ42 peptide have different propensities to bind small molecules, particularly the hydrophobic residues from Leu17-Ala21.

The mechanism for how the N-terminus blocks or slows oligomer stacking and fibril formation is not yet known. The observation of large inhibitor-induced changes at Arg5 and Phe20 suggests that Arg5 may interact directly with Phe20 of the central KLVFF sequence. The KLVFF sequence is known to mediate fibril formation; parallel and in-register cross-β-structure is found for the KLVFF sequence in both in Aβ4035 and Aβ42.36 As a result, the intramolecular interaction of the N-terminus with the KLVFF sequence may interfere with the formation of intramolecular β-hairpin structure and intermolecular β-sheet formation.

A peptide inhibitor corresponding to the KLVFF sequence was one of the earliest peptides described as an inhibitor to Aβ aggregation.63 For comparison, we also characterized the interaction of this inhibitor with Aβ42. No effect of the KLVFF peptide inhibitor on Aβ chemical shifts was observed (Figure S6C) or on the height of Aβ oligomers (data not shown). In contrast, the RSTWESKWR peptide, which was designed to interact with Aβ42,36 shows large chemical shift changes in the N-terminal and central regions of the peptide (Figure S6B). The peptide inhibitor RSTWESKWR is a second-generation peptide inhibitor designed in our laboratory based on modifications of our earlier inhibitors,36 which have been previously shown to cap Aβ42 oligomers.44 We found that the RSTWESKWR peptide interacts with the same amino acids on Aβ42 as curcumin and resveratrol, namely Glu3 through Ser8, Gln15 through Leu17 and Phe20 (Figure S6B). However, the chemical shift changes are larger upon binding of RSTWESKWR. The similarity in binding and ability to cap the Aβ oligomers suggests a similar mechanism of inhibition for curcumin, resveratrol and RSTWESKWR.

Our original designed peptide inhibitor I1 (RGTFEGKF-NH2) was based on the C-terminal G33xxxG37 sequence in the Aβ peptide.36 The two phenylalanines in the I1 sequence are predicted to lie on the same side of a β-strand and interact with the GxxxG sequence in the Aβ C-terminus. The RSTWESKWR peptide contains two serines in the positions of the glycines, which improve solubility, and two tryptophans at the positions of the phenylalanines. These peptide inhibitors are similar to the C-terminal fragments of Aβ described by Bitan and co-workers64,65 (i.e., Aβ(30–42) and Aβ(31–42)) that were found to be potent inhibitors of Aβ42 oligomerization and toxicity. This group found that N-methyl amino acids at positions 3,8,9, 11 (i.e., G33, G38, V39, I41) improved solubility and increased inhibition of toxicity.66 They proposed that the peptides disrupted the association of both intramolecular and intermolecular β-strands.67 They found that the C-terminal tetra peptide interacted with the N-terminus of Aβ (residues D1, R5, D7, as well as D23).68

N-terminal interactions have also been observed with the binding of the myelin basic protein, a natural Aβ inhibitor in the brain.69 The myelin basic protein also has the ability to cap the height of Aβ and block fibril formation. In studies on an Aβ40 sequence containing the Dutch (E22Q) and Iowa (D23N) mutations, the addition of myelin basic protein resulted in short protofibril-like oligomers that were ∼2 nm in height (i.e., half the height of mature fibrils).70

In all of the Aβ inhibitors that capped the height of the soluble oligomers, there was an observed reduction in toxicity. We present results showing that both curcumin and resveratrol reduce toxicity using the MTT assay in Figure S8. This supports the idea that the monomers and low MW oligomers are less toxic than the high MW oligomers and protofibrils. These results are in close agreement with Li et al.23 who found that stabilizing small oligomers (hydrodynamic radius of 8–12 nm) reduced toxicity, while formation of oligomers with a radius of 20–60 nm increased toxicity. Gazit and co-workers also found that their inhibitors reduced the formation of toxic ∼56 kDa Aβ42 oligomers, but did not affect the formation of the low MW Aβ42 oligomers.22

Possible Mechanisms of Noncapping Small Molecule Inhibitors

In contrast to inhibitors that bind to the N-terminus, the two NSAIDs (sulindac sulfide and indomethacin), which were previously found to bind to Aβ42, were not effective in capping the low MW oligomers. For both of these inhibitors, the 1H–15N HSQC spectra revealed only small chemical shift changes across the length of the Aβ42 sequence in our comparative study (Figure 6, Table S1), suggesting very weak interactions, at least with the Aβ monomer.

One possibility is that these molecules primarily interact with the high MW Aβ oligomers. In the discussion above, we have suggested that formation of the high MW oligomers is through stacking of the hydrophobic surface of low MW oligomers. This hydrophobic core (composed of the C-terminal Aβ residues) may serve as the binding site for this second class of Aβ inhibitor.

A second possibility is that these inhibitors do not interact with oligomers but rather interact with Aβ42 protofibrils or fibrils. Sulindac sulfide, which was reported to interact with the C-terminus of Aβ42, was proposed to bind to the β-sheet structure within Aβ fibrils.37 In two similar studies, binding of inhibitors to the hydrophobic C-terminus of Aβ led to increased fibril formation. In the first study, Wanker and colleagues recently found that an orcein-related small molecule inhibitor (O4) interacts with the C-terminus and inhibits Aβ42 toxicity by increasing the rate of protofibril formation.71 They modeled the interaction of this inhibitor with the surface of Aβ fibrils, and suggested that these inhibitors lower the concentration of toxic oligomers by increasing the rate of conversion of high MW oligomers into fibrils.71 Connors et al.72 found that the binding of tranilast to residues in the hydrophobic C-terminal region of Aβ monomers led to increased fibril formation. They suggested that binding of the inhibitor within a hydrophobic pocket formed by the C-terminal residues causes a shift to Aβ species capable of seed formation and fibril elongation.

Summary

In this study, we compare the interaction of two natural products (curcumin and resveratrol) and two nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (sulindac sulfide and indomethacin) with Aβ42 monomers and oligomers. We first show that monomeric Aβ42 forms low MW oligomers with heights (measured by AFM) of ∼1.0–2.5 nm, and suggest that these oligomers stack to form the high MW oligomers with heights of 3–5 nm. Our studies show that the location of inhibitor binding influences their ability to block the formation of the high MW oligomers. We observe a correlation between N-terminal binding of three different inhibitors (curcumin, resveratrol, and RSTWESKWR) and capping of the low MW oligomers. In contrast, the inhibitors that have nonspecific binding across the Aβ sequence (indomethacin and sulindac sulfide) do not cap oligomers and function by a different mechanism of inhibition. These compounds may be part of a larger set of small molecules that bind to Aβ fibrils and possibly shift the equilibrium from toxic high MW oligomers and protofibrils.73 Further studies on these inhibitors that only very weakly bind to Aβ will be needed to understand their mechanism of inhibition.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- MW

molecular weight

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NSAIDs

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Supporting Information Available

Figure S1, DMSO slows the kinetics of Aβ42 fibril formation; Figure S2, stability of curcumin increases in the presence of Aβ42; Figure S3, single touch AFM of B-DNA; Figure S4, low temperature-stabilized Aβ42 is largely monomeric; Figure S5, TEM images of Aβ42 as a function of incubation time; Figure S6, solution NMR spectroscopy of Aβ42 with peptide inhibitors and thioflavin T; Figure S7, structure and water accessibility of Aβ42 monomers; Figure S8, toxicity of Aβ42 peptides in the presence and absence of curcumin and resveratrol; Table S1, chemical shift changes upon inhibitor binding; Tables S2–S7, individual 1H and 15N chemical shifts of Aβ42 with inhibitors. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ Z.F. and D.A. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Selkoe D. J.; Schenk D. (2003) Alzheimer’s disease: Molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 545–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. W.; Thompson R.; Zhang H.; Xu H. (2011) APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Brain 4, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. (1999) Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 399, A23–A31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portelius E.; Bogdanovic N.; Gustavsson M.; Volkmann I.; Brinkmalm G.; Zetterberg H.; Winblad B.; Blennow K. (2010) Mass spectrometric characterization of brain amyloid beta isoform signatures in familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 120, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe M. S. (2007) When loss is gain: Reduced presenilin proteolytic function leads to increased Aβ42/Aβ40 - Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. EMBO Rep. 8, 136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M. P.; Barlow A. K.; Chromy B. A.; Edwards C.; Freed R.; Liosatos M.; Morgan T. E.; Rozovsky I.; Trommer B.; Viola K. L.; Wals P.; Zhang C.; Finch C. E.; Krafft G. A.; Klein W. L. (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D. M.; Klyubin I.; Fadeeva J. V.; Cullen W. K.; Anwyl R.; Wolfe M. S.; Rowan M. J.; Selkoe D. J. (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C.; Selkoe D. J. (2007) Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S.; Koh M. T.; Kotilinek L.; Kayed R.; Glabe C. G.; Yang A.; Gallagher M.; Ashe K. H. (2006) A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature 440, 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. I. A.; Linse S.; Luheshi L. M.; Hellstrand E.; White D. A.; Rajah L.; Otzen D. E.; Vendruscolo M.; Dobson C. M.; Knowles T. P. J. (2013) Proliferation of amyloid-beta 42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9758–9763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida M. L.; Caraci F.; Pignataro B.; Cataldo S.; De Bona P.; Bruno V.; Molinaro G.; Pappalardo G.; Messina A.; Palmigiano A.; Garozzo D.; Nicoletti F.; Rizzarelli E.; Copani A. (2009) β-Amyloid monomers are neuroprotective. J. Neurosci. 29, 10582–10587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S.; Sarkar B.; Bandyopadhyay A.; Sahoo B.; Sreenivasan V. K. A.; Kombrabail M.; Muralidharan C.; Maiti S. (2011) Nature of the amyloid-β monomer and the monomer-oligomer equilibrium. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13827–13833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L. M.; Shao H. Y.; Zhang Y. B.; Li H.; Menon N. K.; Neuhaus E. B.; Brewer J. M.; Byeon I. J. L.; Ray D. G.; Vitek M. P.; Iwashita T.; Makula R. A.; Przybyla A. B.; Zagorski M. G. (2004) Solution NMR studies of the Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) peptides establish that the met35 oxidation state affects the mechanism of amyloid formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1992–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi N. L.; Ying J.; Ghirlando R.; Torchia D. A.; Clore G. M. (2011) Atomic-resolution dynamics on the surface of amyloid-β protofibrils probed by solution NMR. Nature 480, 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers E. T.; Powers D. L. (2008) Mechanisms of protein fibril formation: Nucleated polymerization with competing off-pathway aggregation. Biophys. J. 94, 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomakin A.; Chung D. S.; Benedek G. B.; Kirschner D. A.; Teplow D. B. (1996) On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta-protein fibrils: Detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 1125–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine W. B.; Dahlgren K. N.; Krafft G. A.; LaDu M. J. (2003) In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11612–11622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M.; Davis J.; Aucoin D.; Sato T.; Ahuja S.; Aimoto S.; Elliott J. I.; Van Nostrand W. E.; Smith S. O. (2010) Structural conversion of neurotoxic amyloid-β1–42 oligomers to fibrils. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chromy B. A.; Nowak R. J.; Lambert M. P.; Viola K. L.; Chang L.; Velasco P. T.; Jones B. W.; Fernandez S. J.; Lacor P. N.; Horowitz P.; Finch C. E.; Krafft G. A.; Klein W. L. (2003) Self-assembly of Aβ1–42 into globular neurotoxins. Biochemistry 42, 12749–12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein S. L.; Dupuis N. F.; Lazo N. D.; Wyttenbach T.; Condron M. M.; Bitan G.; Teplow D. B.; Shea J.; Ruotolo B. T.; Robinson C. V.; Bowers M. T. (2009) Amyloid-β protein oligomerization and the importance of tetramers and dodecamers in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Chem. 1, 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G.; Kirkitadze M. D.; Lomakin A.; Vollers S. S.; Benedek G. B.; Teplow D. B. (2003) Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly: Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 330–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman-Marom A.; Rechter M.; Shefler I.; Bram Y.; Shalev D. E.; Gazit E. (2009) Cognitive-performance recovery of Alzheimer’s disease model mice by modulation of early soluble amyloidal assemblies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 48, 1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Monien B. H.; Lomakin A.; Zemel R.; Fradinger E. A.; Tan M.; Spring S. M.; Urbanc B.; Xie C.-W.; Benedek G. B.; Bitan G. (2010) Mechanistic investigation of the inhibition of Aβ42 assembly and neurotoxicity by Aβ42 C-terminal fragments. Biochemistry 49, 6358–6364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barghorn S.; Nimmrich V.; Striebinger A.; Krantz C.; Keller P.; Janson B.; Bahr M.; Schmidt M.; Bitner R. S.; Harlan J.; Barlow E.; Ebert U.; Hillen H. (2005) Globular amyloid β-peptide1–42 oligomer - a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 95, 834–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M.; Li S. M.; Mehta T. H.; Garcia-Munoz A.; Shepardson N. E.; Smith I.; Brett F. M.; Farrell M. A.; Rowan M. J.; Lemere C. A.; Regan C. M.; Walsh D. M.; Sabatini B. L.; Selkoe D. J. (2008) Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D. J.; Meredith S. C. (2003) Probing the role of backbone hydrogen bonding in β-amyloid fibrils with inhibitor peptides containing ester bonds at alternate positions. Biochemistry 42, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes E.; Burke R. M.; Doig A. J. (2000) Inhibition of toxicity in the β-amyloid peptide fragment β-(25–35) using N-methylated derivatives—A general strategy to prevent amyloid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25109–25115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapurniotu A.; Schmauder A.; Tenidis K. (2002) Structure-based design and study of non-amyloidogenic, double N-methylated IAPP amyloid core sequences as inhibitors of IAPP amyloid formation and cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 315, 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C.; Kindy M. S.; Baumann M.; Frangione B. (1996) Inhibition of Alzheimer’s amyloidosis by peptides that prevent β-sheet conformation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 226, 672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C.; Sigurdsson E. M.; Morelli L.; Kumar R. A.; Castano E. M.; Frangione B. (1998) β-sheet breaker peptides inhibit fibrillogenesis in a rat brain model of amyloidosis: Implications for Alzheimer’s therapy. Nat. Med. 4, 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adessi C.; Frossard M. J.; Boissard C.; Fraga S.; Bieler S.; Ruckle T.; Vilbois F.; Robinson S. M.; Mutter M.; Banks W. A.; Soto C. (2003) Pharmacological profiles of peptide drug candidates for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13905–13911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjernberg L. O.; Lilliehook C.; Callaway D. J. E.; Naslund J.; Hahne S.; Thyberg J.; Terenius L.; Nordstedt C. (1997) Controlling amyloid β-peptide fibril formation with protease-stable ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12601–12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necula M.; Kayed R.; Milton S.; Glabe C. G. (2007) Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation indicate that amyloid β oligomerization and fibrillization pathways are independent and distinct. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10311–10324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett J. T.; Berger E. P.; Lansbury P. T. (1993) The carboxy terminus of the β-amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation—Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 32, 4693–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko R. (2011) Solid-State NMR sudies of amyloid fibril structure. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 62, 279–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T.; Kienlen-Campard P.; Ahmed M.; Liu W.; Li H.; Elliott J. I.; Aimoto S.; Constantinescu S. N.; Octave J. N.; Smith S. O. (2006) Inhibitors of amyloid toxicity based on β-sheet packing of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Biochemistry 45, 5503–5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L.; Munter L.-M.; Ness J.; Hildebrand P. W.; Dasari M.; Unterreitmeier S.; Bulic B.; Beyermann M.; Gust R.; Reif B.; Weggen S.; Langosch D.; Multhaup G. (2010) Amyloid beta 42 peptide (Aβ42)-lowering compounds directly bind to Aβ and interfere with amyloid precursor protein (APP) transmembrane dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 14597–14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. D.; Portelius E.; Kheterpal I.; Guo J. T.; Cook K. D.; Xu Y.; Wetzel R. (2004) Mapping Aβ amyloid fibril secondary structure using scanning proline mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. D.; Shivaprasad S.; Wetzel R. (2006) Alanine scanning mutagenesis of Aβ(1–40) amyloid fibril stability. J. Mol. Biol. 357, 1283–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandersteen A.; Hubin E.; Sarroukh R.; De Baets G.; Schymkowitz J.; Rousseau F.; Subramaniam V.; Raussens V.; Wenschuh H.; Wildemann D.; Broersen K. (2012) A comparative analysis of the aggregation behavior of amyloid-β peptide variants. FEBS Lett. 586, 4088–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nostrand W. E.; Porter M. (1999) Plasmin cleavage of the amyloid beta-protein: Alteration of secondary structure and stimulation of tissue plasminogen activator activity. Biochemistry 38, 11570–11576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y.; Hashimoto T.; Wakutani Y.; Urakami K.; Nakashima K.; Condron M. M.; Tsubuki S.; Saido T. C.; Teplow D. B.; Iwatsubo T. (2007) The Tottori (D7N) and English (H6R) familial Alzheimer disease mutations accelerate A beta fibril formation without increasing protofibril formation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4916–4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fede G.; Catania M.; Morbin M.; Rossi G.; Suardi S.; Mazzoleni G.; Merlin M.; Giovagnoli A. R.; Prioni S.; Erbetta A.; Falcone C.; Gobbi M.; Colombo L.; Bastone A.; Beeg M.; Manzoni C.; Francescucci B.; Spagnoli A.; Cantu L.; Del Favero E.; Levy E.; Salmona M.; Tagliavini F. (2009) A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science 323, 1473–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo I. A.; Ahmed M.; Sato T.; Liu W.; Wang C.; Hough P.; Smith S. O. (2006) High-resolution atomic force microscopy of soluble Aβ42 oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 358, 106–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. L.; Wang C. Y. (2006) Aβ42 is more rigid than Aβ40 at the C terminus: Implications for Aβ aggregation and toxicity. J. Mol. Biol. 364, 853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreghan B.; Kosmoski J.; Glabe C. (1994) Surfactant properties of Alzheimers Aβ peptides and the mechanism of amyloid aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28551–28554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi T.; Ono K.; Yamada M. (2010) Curcumin and Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 16, 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K.; Li L.; Takamura Y.; Yoshiike Y.; Zhu L.; Han F.; Mao X.; Ikeda T.; Takasaki J.; Nishijo H.; Takashima A.; Teplow D.; Zagorski M.; Yamada M. (2012) Phenolic compounds prevent amyloid β-protein oligomerization and synaptic dysfunction by site specific binding. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 14631–14643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Wang X. P.; Yang S. G.; Wang Y. J.; Zhang X.; Du X. T.; Sun X. X.; Zhao M.; Huang L.; Liu R. T. (2009) Resveratrol inhibits beta-amyloid oligomeric cytotoxicity but does not prevent oligomer formation. Neurotoxicology 30, 986–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirohata M.; Ono K.; Naiki H.; Yamada M. (2005) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have anti-amyloidogenic effects for Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. Neuropharmacology 49, 1088–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. J.; Pan M. H.; Cheng A. L.; Lin L. L.; Ho Y. S.; Hsieh C. Y.; Lin J. K. (1997) Stability of curcumin in buffer solutions and characterization of its degradation products. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 15, 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi N. L.; Ying J. F.; Torchia D. A.; Clore G. M. (2010) Kinetics of amyloid β monomer-to-oligomer exchange by NMR relaxation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9948–9951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine H. (1999) Quantification of β-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 309, 274–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs M. R. H.; Bromley E. H. C.; Donald A. M. (2005) The binding of thioflavin-T to amyloid fibrils: Localisation and implications. J. Struct. Biol. 149, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho-Cerqueira E.; Pinheiro A. S.; Follmer C. (2014) Pitfalls associated with the use of thioflavin-T to monitor anti-fibrillogenic activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3194–3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Gessel M. M.; Wisniewski M. L.; Viswanathan K.; Wright D. L.; Bahr B. A.; Bowers M. T. (2012) Z-Phe-Ala-diazomethylketone (PADK) disrupts and remodels early oligomer states of the Alzheimer disease Aβ42 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 6084–6088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kłoniecki M.; Jabłonowska A.; Poznański J.; Langridge J.; Hughes C.; Campuzano I.; Giles K.; Dadlez D. (2011) Ion mobility separation coupled with MS detects two structural states of Alzheimer’s disease Aβ1–40 peptide oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 110–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riek R.; Guntert P.; Döbeli H.; Wipf B.; Wüthrich K. (2001) NMR studies in aqueous solution fail to identify significant conformational differences between the monomeric forms of two Alzheimer peptides with widely different plaque-competence, Aβ(1–40)ox and Aβ(1–42)ox. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 5930–5936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivekanandan S.; Brender J. R.; Lee S. Y.; Ramamoorthy A. (2011) A partially folded structure of amyloid-beta(1–40) in an aqueous environment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 411, 312–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hard T. (2011) Protein engineering to stabilize soluble amyloid beta-protein aggregates for structural and functional studies. FEBS J. 278, 3884–3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski T.; Holtzman D. M. (1999) In situ atomic force microscopy study of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide on different substrates: new insights into mechanism of β-sheet formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 3688–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; De Simone A.; Schenk D.; Toth G.; Dobson C. M.; Vendruscolo M. (2013) Identification of small-molecule binding pockets in the soluble monomeric form of the Aβ42 peptide. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjernberg L. O.; Naslund J.; Lindqvist F.; Johansson J.; Karlstrom A. R.; Thyberg J.; Terenius L.; Nordstedt C. (1996) Arrest of β-amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 8545–8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B.; Betnel M.; Cruz L.; Li H.; Fradinger E. A.; Monien B. H.; Bitan G. (2011) Structural basis for abeta(1–42) toxicity inhibition by abeta C-terminal fragments: discrete molecular dynamics study. J. Mol. Biol. 410, 316–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Y.; Monien B. H.; Fradinger E. A.; Urbanc B.; Bitan G. (2010) Biophysical characterization of Aβ 42 C-terminal fragments: Inhibitors of Aβ 42 neurotoxicity. Biochemistry 49, 1259–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Zemel R.; Lopes D. H. J.; Monien B. H.; Bitan G. (2012) A two-step strategy for structure-activity relationship studies of N-methylated Aβ42 C-terminal rragments as Aβ42 toxicity inhibitors. ChemMedChem 7, 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.; Murray M. M.; Bernstein S. L.; Condron M. M.; Bitan G.; Shea J.-E.; Bowers M. T. (2009) The structure of Aβ42 C-terminal fragments probed by a combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Mol. Biol. 387, 492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Du Z.; Lopes D. H. J.; Fradinger E. A.; Wang C.; Bitan G. (2011) C-terminal tetrapeptides inhibit Aβ42-induced neurotoxicity primarily through specific interaction at the N-terminus of Aβ42. J. Med. Chem. 54, 8451–8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotarba A. E.; Aucoin D.; Hoos M. D.; Smith S. O.; Van Nostrandt W. E. (2013) Fine mapping of the amyloid β-protein binding site on myelin basic protein. Biochemistry 52, 2565–2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoos M. D.; Ahmed M.; Smith S. O.; van Nostrand W. E. (2007) Inhibition of familial cerebral amyloid angiopathy mutant amyloid β-protein fibril assembly by myelin basic protein. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9952–9961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke J.; Herbst M.; Wiglenda T.; Friedrich R. P.; Boeddrich A.; Schiele F.; Kleckers D.; del Amo J. M. L.; Grüning B. A.; Wang Q.; Schmidt M. R.; Lurz R.; Anwyl R.; Schnoegl S.; Fändrich M.; Frank R. F.; Reif B.; Günther S.; Walsh D. M.; Wanker E. E. (2012) Small-molecule conversion of toxic oligomers to nontoxic β-sheet-rich amyloid fibrils. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman D. J.; Connors C. R.; Chen W.; Wang C.; Garcia A. E. (2013) Abeta monomers transiently sample oligomer and fibril-like configurations: ensemble characterization using a combined MD/NMR approach. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 3338–3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.; Liu C.; Leibly D.; Landau M.; Zhao M. L.; Hughes M. P.; Eisenberg D. S. (2013) Structure-based discovery of fiber-binding compounds that reduce the cytotoxicity of amyloid beta. eLife 2, e00857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzenko K. A.; Weltzien R. B.; Pachter J. S. (1997) Suppression of A beta-induced monocyte neurotoxicity by antiinflammatory compounds. J. Neuroimmunol. 80, 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J.; Park S. H.; Opella S. J.; Marsilje T. H.; Michellys P. Y.; Seidel H. M.; Tian S. S. (2007) NMR structural studies of interactions of a small, nonpeptidyl Tpo mimic with the thrombopoietin receptor extracellular juxtamembrane and transmembrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 14253–14261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.