Abstract

Background

Follow-up after a positive colorectal cancer (CRC) screening test is necessary for screening to be effective. We hypothesized that nurse navigation would increase colonoscopy completion after a positive screening test.

Methods

This study was conducted between 2008 and 2012 at 21 primary care medical centers in Western Washington. Participants in the Systems of Support to Increase CRC Screening (SOS) study who had a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or flexible sigmoidoscopy were randomized to usual care (UC) or nurse navigator (Navigation). UC included an electronic health record (EHR)-based positive FOBT registry and physician reminder system. Navigation included UC plus care coordination and patient self-management support from a registered nurse who tracked and assisted patients until they completed or refused colonoscopy. The primary outcome was colonoscopy completion within 6 months. After 6 months, both groups received navigation.

Results

147 participants with a positive FOBT or sigmoidoscopy were randomized. Colonoscopy completion was higher in the intervention group at 6 months, but differences were not statistically significant (Navigation 91.0% vs. UC 80.8%, adjusted difference 10.1%; P=.0.10). Reasons for no or late colonoscopies included refusal, failure to schedule or missed appointments, concerns about risks or costs, and competing health concerns.

Conclusions

Navigation did not lead to a statistically significant incremental benefit at 6 months.

Impact

Follow-up rates after a positive CRC screening test are high in a health care system where UC included a registry and physician reminders. Because of small sample size we cannot rule out incremental benefits of nurse navigation.

Keywords: colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy, complete diagnostic evaluation, navigation

There is strong evidence that colorectal cancer (CRC) screening decreases CRC incidence and mortality.1 Despite the efficacy of screening, almost 40% of eligible adults are not screened at recommended intervals2, and many have never had any type of CRC screening. Screening failures occur not only from lack of screening but also from breakdowns in follow-up of positive tests, which obviate the benefits of screening.

Complete diagnostic evaluation with optical colonoscopy is recommended after a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or a positive flexible sigmoidoscopy, i.e., when precancerous lesions are found or polyp resection is incomplete. In randomized controlled trials, diagnostic evaluation completion rates have ranged between 83% and 90%.3–5 However, in community-based studies, completion of recommended follow-up is much lower, with rates of 30% to 65% reported.6–9 Lack of diagnostic follow-up after a CRC screening test has been associated with increased risk of CRC death10,11 and is potentially a medico-legal issue.12,13

To test a method of improving follow-up, patients who had a positive FOBT or sigmoidoscopy were randomized to receive either UC (which included a positive FOBT registry and provider reminder system) or this plus nurse navigation to support care coordination (colonoscopy scheduling) and patient self-care (preparing for and completing testing). We hypothesized that nurse navigation would lead to increased rates and more rapid completion of diagnostic testing after a positive screening test.

Methods

This study was a follow-up trial within the larger Systems of Support to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Study (SOS) conducted from August 2008 through June 2012. The methods and design14 and screening outcomes15 for the main study, which tested incremental levels of support to increase CRC screening rates, have been published. The study was conducted at 21 primary care clinics of Group Health Cooperative, a large nonprofit integrated health care delivery system in Washington State.

Participants aged 50–74 were eligible for the follow-up trial if they had a positive FOBT (Beckman Coulter, SENSA®, Brea CA), with one or more of three cards guaiac-positive for blood, or a flexible sigmoidoscopy with an adenomatous lesion or incomplete polyp resection while they were participating in the main SOS trial. Patients were not eligible for the follow-up study if they had a diagnosis of CRC prior to the positive test; had a colonoscopy after enrollment in the parent study but prior to the positive FOBT or flexible sigmoidoscopy; died; or left the health plan prior to the positive screening test. The Group Health Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number R01CA121125; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00697047.

Randomization

An electronic database captured positive screening tests and automatically randomized participants in equal proportions to usual care (UC) or nurse navigation (Navigation). Concealed random allocation sequences with a block size of 4, stratified by clinic and by whether the participant had a positive FOBT or a positive sigmoidoscopy were generated by a computer program.

Blinding

Investigators were blinded to outcomes until all data were collected. Because of the nature of the intervention, the navigator and patient could not be blinded to interventions.

Usual Care (UC) and Interventions

UC at Group Health included a positive FOBT registry.16 Primary care providers (mainly physicians) were sent electronic health record (EHR) reminders about their patients with a positive FOBT who had not completed a colonoscopy until either the patient completed testing or until the provider filled out an exception form stating why colonoscopy was not indicated (e.g., patient refused, too ill, or left health plan and had been notified to follow up with new provider). Medical center chiefs received lists of providers who had patients without diagnostic follow-up or exception forms. Follow-up after a positive sigmoidoscopy was the responsibility of the performing provider and/or the patient’s physician and was not part of the FOBT registry.

Patients randomized to the intervention arm received UC plus nurse navigation interventions that targeted the six domains of Wagner’s Chronic Care Model (CCM) including evidence-based decision and self-management support, clinical information systems, delivery system design, health care organization, and community resources.17 Some of these components were already part of UC at Group Health. The navigation intervention additionally emphasized delivery system design (care coordination, linking patients to community resources) and self-management support (addressing patients’ barriers).

Study nurse navigators were registered nurses already practicing within Group Health who had additional paid time to provide study interventions. They used the study database to identify new patients randomized to the Navigation arm and track ongoing interventions (referral, appointing, pre-colonoscopy preparation needs) until the patient completed a diagnostic colonoscopy or the provider adequately documented in the EHR the reason that colonoscopy was not done. Upon notification of a new participant, the nurse reviewed the patient’s EHR to determine what follow-up had already occurred. If processes of care were not underway, or were incomplete, the nurse contacted the patient and their physician as appropriate. The nurse assisted the patient in completing colonoscopy, including resolving barriers such as understanding insurance coverage, making an appointment, planning for preparation and transportation, and addressing concerns or ambivalence about testing. The nurses used motivational interviewing techniques and their phone conversations with participants were periodically monitored or directly observed by study personnel. After diagnostic testing was completed, the nurse also ensured that documentation was complete, including ensuring that a copy of the colonoscopy procedure report and pathology (if a biopsy was performed) had been entered into the EHR.

Measures

The primary outcome was completion of colonoscopy within 6 months (defined as 184 days) of the positive screening test. Colonoscopy is the preferred diagnostic test after a positive FOBT or sigmoidoscopy at Group Health. No study participants received alternative testing such as computerized colonography or sigmoidoscopy combined with barium enema. EHR procedure and claims data were used to determine if a colonoscopy was completed, and the date of the exam (nurse or patient self-report of colonoscopy were excluded because of the possibility of ascertainment bias). Secondary outcomes included time to completion and reasons for lack of or late colonoscopy. Late colonoscopy was defined as one occurring after 6 months. Chart audit and nurse navigator entries into the study database were used to assess reasons for non-completion.

Analysis

Power estimates were based on the assumptions that 7000 patients would be randomized in the main SOS study, 45% would complete a FOBT with a 6% positive rate, and 8.5% would complete a flexible sigmoidoscopy with a 12% positive rate.14 These assumptions resulted in an estimated 260 participants eligible for the follow-up study, providing 80% power to detect a 15% difference between groups, assuming the colonoscopy completion rate within 6 months was 65% among the UC group. Analyses were completed using Stata statistical software, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

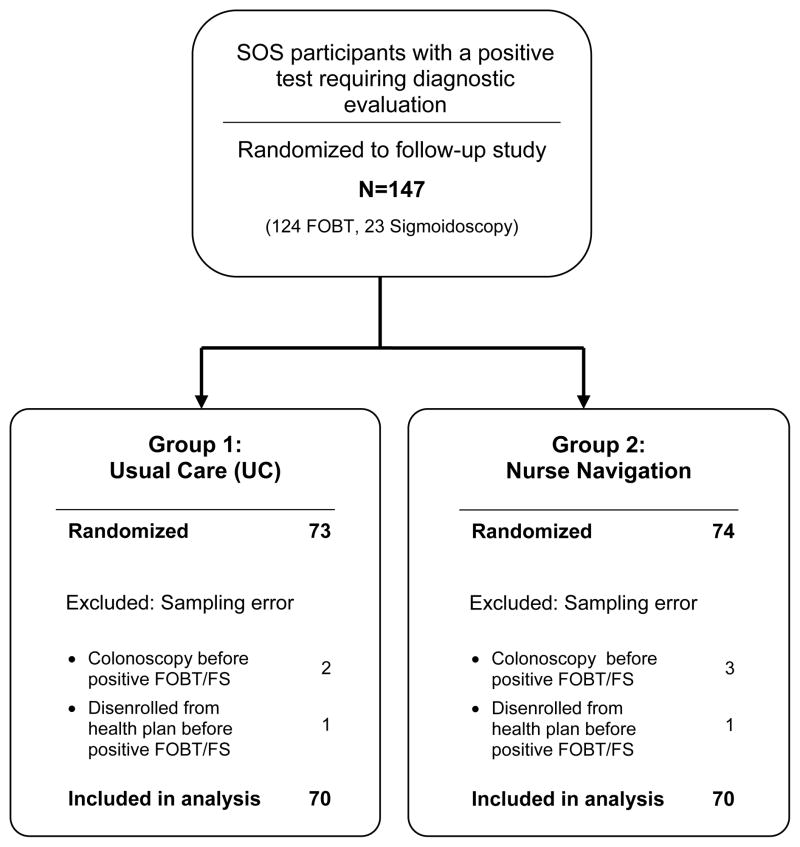

The analysis was based on intent-to-treat principles. Participants were included in the analysis according to the randomization group to which they were assigned regardless of intervention received. However, randomized participants were excluded from the analysis if they had been sampled in error, i.e., they had received a colonoscopy or disenrolled from the health plan after randomization into the main SOS study but prior to the positive FOBT or positive sigmoidoscopy that flagged them for the follow-up study (Figure 1). Logistic regression models were used to estimate predictive margins for the binary primary outcome of colonoscopy completion within 6 months of the positive screening test. Predictive margins are estimated probabilities adjusting across the covariate distribution in the sample. Differences between groups are reported as relative risks and risk differences, with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram of the System of Support Trial Study Participants with a Positive Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) or Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

Results

Of the 4664 participants in the main SOS trial, 124 participants had a positive FOBT and 23 had a sigmoidoscopy needing follow-up, with 147 randomized. Participants sampled in error were excluded from analysis, including 5 participants who received a colonoscopy prior to the positive FOBT and 2 who left the health plan prior to completing the FOBT, leaving 140 participants analyzed (Figure 1). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the UC and Navigation arms. The majority was younger than age 65 and white. UC was somewhat more likely to have less formal education and slightly more likely to be married.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomization Group of System of Support Trial Study Participants with a Positive Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) or Flexible Sigmoidoscopy (N = 140)

| Characteristics | Usual Care N=70 |

Nurse Navigation N=70 |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age group at baseline (years) | ||

| 50 – 64 | 54 (77) | 57 (81) |

| 65 – 73 | 16 (23) | 13 (19) |

| Female | 31 (44) | 33 (47) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 51 (73) | 55 (79) |

| General Health | ||

| Excellent/Very good | 41 (59) | 40 (57) |

| Good | 21 (30) | 23 (33) |

| Fair/Poor | 8 (11) | 7 (10) |

| Married or living with partner | 52 (74) | 44 (63) |

| Highest education | ||

| High school grad, GED, or less | 17 (24) | 8 (11) |

| Some college | 24 (34) | 22 (31) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 29 (41) | 40 (57) |

| Never been screened for CRC | 28 (40) | 27 (39) |

| First degree relative with CRC | 6 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Type of positive study test | ||

| FOBT | 59 (84) | 59 (84) |

| Flexible Sigmoidoscopy | 11 (16) | 11 (16) |

Overall, 85.7% (120/140) had a colonoscopy within 6 months of the positive screening test. Colonoscopy completion within 6 months was higher in the Navigation arm than UC, but differences were not statistically significant (adjusted proportions: Navigation 91.0% vs. UC 80.8%, adjusted net difference 10.1%; P=0.10). Six-month colonoscopy completion rates were not influenced by type of positive screening test (positive FOBT 79.7% vs. 90.0%; positive sigmoidoscopy 81.8% UC vs. 90.9% for UC compared to navigation respectively). The time between positive screening test and colonoscopy among participants who completed colonoscopy was similar across intervention groups, with a mean of 53.6 days (SD 35.6) in UC, and 56.5 days (SD 38.0) in the Navigation arm.

Of the 20 participants without colonoscopy at 6 months (14 in UC and 6 in Navigation), 9 had a colonoscopy within 12 months (5 in UC and 4 in Navigation). One additional participant in UC completed colonoscopy at 13 months, and 10 had no follow-up testing. The overall percent completing colonoscopy within 13 months was 92.9% (130/140).

Chart audits were done to assess reasons for lack of and late diagnostic follow-up (Supplemental Table 1). As previously noted, both arms received navigation interventions if a colonoscopy was not completed by 6 months. All UC and Navigation patients received colonoscopy referrals from their primary care physicians. In three instances UC patients with either a positive FOBT (N=2) or sigmoidoscopy (N=1) were referred but had not received an appointment until after the nurse navigator assisted them with scheduling. Other reasons for late colonoscopy for both UC and Navigation included canceled and missed appointments, concerns about colonoscopy risk, being too busy, competing health issues, or losing or changing health insurance. Reasons for no colonoscopy for both groups included active refusal, passive refusal by missing appointments, losing health insurance, and serious health issues.

Discussion

Although Navigation led to a 10% net increase over UC for receipt of a colonoscopy within 6 months, group differences were not statistically significant. A limitation of our study was that the power calculations were based on a planned sample size of 260, but only 147 participants were randomized. Budget cuts required decreasing the sample size of the main SOS trial from 7000 to 5000 participant, with fewer participants being eligible for the follow-up study.14 Additionally, the number of positive screening tests in the main trial was lower than projected.

Another explanation for lack of differences between the groups is a ceiling effect. Follow-up rates were high in UC, probably due to the registry, with physicians receiving ongoing reminders until either colonoscopy was completed or the reason for non-completion was documented in the EHR. Miglioretti et al.16 reported in 2008 that in this healthcare system, diagnostic evaluation follow-up rates within one-year of a positive FOBT were 60% between 1993 and 1996 but had increased to 82% by 2006 (3 years after implementation of the positive FOBT registry). The SOS study was already underway when we received this information and we chose to continue study interventions because of the possibility that we might still find significant differences between groups.

Other studies that included navigation interventions have had mixed results. Raich et al.18, using a community health worker navigator program in a safety-net clinic health care system, found improvements in rates of diagnostic resolution (79% vs. 58%, p<0.002) and time to resolution. In contrast, Wells et al.19, using a community health worker navigation intervention tailored for minority groups, failed to find significant differences in resolution rates after a positive FOBT. Paskett et al.20 tested whether nurse navigation improved time to resolution after abnormal cervical, breast, or colorectal screening tests or symptoms. Navigation decreased time to diagnostic resolution as compared to UC, with greater differences between groups appearing over time suggesting that prolonged interventions with persistent reminders might lead to eventual colonoscopy completion. In our study, UC received navigation after 6 months, and the overall proportion with colonoscopy follow-up continued to increase for both groups, particularly for Navigation (only two patients did not have colonoscopy), supporting the view that some patients may benefit from prolonged interventions. Follow-up interventions that included systems changes have been more consistently positive. In a cluster trial performed at Veteran’s Administration clinics (Humphrey et al.21), positive fecal tests directly sent to the gastroenterology clinic and use of a standard workflow for appointing patients led to a 31% increase in diagnostic evaluation at 180 days. However follow-up rates were low, with only 50% of the intervention patients completing colonoscopy.

Notable in our study was that all patients received a gastroenterology referral. However, instances of system breakdowns still arose, with patients not receiving calls or making an appointment until reminded by the nurse navigator. Myers et al22 showed that one-on-one physician training and audit and feedback (physicians receiving lists of their patients without complete diagnostic evaluations) resulted in improved completion of diagnostic testing (from a baseline rate of 50% to 63% compared to controls who remained unchanged at 53%, p<0.03). Singh et al.23 assessed a clinic-based quality improvement activity that included provider education, a positive FOBT registry, and improved gastroenterology access. Colonoscopy completion increased from 64% to 76%. In our study the combination of a systems approach (the positive FOBT registry) and either initial or delayed navigation resulted in colonoscopy follow-up rates exceeding 92%. We know of no clinic-based interventions reporting completion rates this high.

Study limitations included the requirement of verbal consent to participate in the main study and volunteers might be more compliant with both screening and completing diagnostic evaluations, and thus not representative of Group Health patients or the general population. Additionally, almost all participants had health insurance, with most policies covering diagnostic colonoscopy, thus these results may not generalize to those without health insurance or high deductible plans. Our interventions may also be less generalizable to community primary care practices that do not directly capture colonoscopy data from external providers and hospitals. However, most primary care practices have EHRs and are increasingly using these or registries for quality improvement and reporting efforts. Navigators could be used to assist community practices in capturing colonoscopy data and outcomes, and update EHRs and registries for the purposes of tracking population-based CRC screening completion, follow-up testing, and ongoing surveillance.

Our study also had several notable strengths. The study reported extremely high positive FOBT or sigmoidoscopy follow-up rates--higher than those previously reported in clinic settings. UC alone, which included a registry and physician reminders, led to very high completion rates and even though our findings were not significant, a 10% improvement could be important because 2–4% of patients with a positive FOBT will have CRC and up to one-third will have advanced adenomas at colonoscopy.24 Larger studies are needed to confirm the independent benefits of registries, potential incremental benefits of navigation, and whether navigation increases diagnostic evaluations beyond six months. Additionally, navigation may have differential benefits in settings without robust systems for follow-up or for populations with health disparities. Future studies in different populations should investigate these potential differences.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Receipt of Colonoscopy with 6 months after a Positive Fecal Occult Blood Test or Flexible Sigmoidoscopy by Randomization Group

| Usual Care N=70 |

Nurse Navigation N=70 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| p-value | |||

| Colonoscopy follow-up within 6-months | |||

| Number completing follow-up | 56 | 64 | |

| Percent* (95% CI) | 80.8 (71.7, 89.9) | 91.0 (84.1, 97.8) | 0.10 |

| Relative risk* (95% CI) | 1.0 (referent) | 1.13 (0.97, 1.28) | |

| Risk difference* (95% CI) | Referent | 10.1 (−1.5, 21.7) | |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, and education

Acknowledgments

Primary Funding Agency: The National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health Registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT00697047.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: the authors have none

References

- 1.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Nov 4;149(9):638–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use - United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(44):881–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(5):434–437. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996 Nov 30;348(9040):1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers RE, Turner B, Weinberg D, et al. Complete diagnostic evaluation in colorectal cancer screening: research design and baseline findings. Prev Med. 2001 Oct;33(4):249–260. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie JD, Welch HG. Diagnostic testing following fecal occult blood screening in the elderly. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Oct 6;91(19):1641–1646. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.19.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baig N, Myers RE, Turner BJ, et al. Physician-reported reasons for limited follow-up of patients with a positive fecal occult blood test screening result. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Sep;98(9):2078–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrat E, Le Breton J, Veerabudun K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: factors associated with colonoscopy after a positive faecal occult blood test. Br J Cancer. 2013 Sep 17;109(6):1437–1444. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torring ML, Frydenberg M, Hamilton W, Hansen RP, Lautrup MD, Vedsted P. Diagnostic interval and mortality in colorectal cancer: U-shaped association demonstrated for three different datasets. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012 Jun;65(6):669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomson CS, Forman D. Cancer survival in England and the influence of early diagnosis: what can we learn from recent EUROCARE results? Br J Cancer. 2009 Dec 3;101 (Suppl 2):S102–S109. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz RL, Rolph JE, Petersen L. Omission-related malpractice claims and the limits of defensive medicine. Med Care Res Rev. 1997 Dec;54(4):456–471. doi: 10.1177/107755879705400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace E, Lowry J, Smith SM, Fahey T. The epidemiology of malpractice claims in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e002929. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002929. pii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green BB, Wang CY, Horner K, et al. Systems of support to increase colorectal cancer screening and follow-up rates (SOS): design, challenges, and baseline characteristics of trial participants. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010 Nov;31(6):589–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green BB, Wang CY, Anderson ML, et al. An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Mar 5;158(5 Pt 1):301–311. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miglioretti DL, Rutter CM, Bradford SC, et al. Improvement in the diagnostic evaluation of a positive fecal occult blood test in an integrated health care organization. Med Care. 2008 Sep;46(9 Suppl 1):S91–S96. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817946c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raich P, Whitley E, Thorland W, Valverde P, Faircloth D Denver Patient Navigation Research Program. Patient navigation improves cancer diagnostic resolution: an individually randomized clinical trial in an underserved population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Oct;21(10):1629–1638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells KJ, Lee JH, Calcano ER, et al. A cluster randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of patient navigation in improving quality of diagnostic care for patients with breast or colorectal cancer abnormalities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Oct;21(10):1664–1672. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paskett ED, Katz ML, Post DM, et al. The Ohio Patient Navigation Research Program: does the American Cancer Society patient navigation model improve time to resolution in patients with abnormal screening tests? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Oct;21(10):1620–1628. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphrey LL, Shannon J, Partin MR, O’Malley J, Chen Z, Helfand M. Improving the follow-up of positive hemoccult screening tests: an electronic intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jul;26(7):691–697. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers RE, Turner B, Weinberg D, et al. Impact of a physician-oriented intervention on follow-up in colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004 Apr;38(4):375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh H, Kadiyala H, Bhagwath G, et al. Using a multifaceted approach to improve the follow-up of positive fecal occult blood test results. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Apr;104(4):942–952. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heitman SJ, Ronksley PE, Hilsden RJ, Manns BJ, Rostom A, Hemmelgarn BR. Prevalence of adenomas and colorectal cancer in average risk individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Dec;7(12):1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.