Abstract

Nitrous oxide (N2O) gas is a widely used anesthetic adjunct in dentistry and medicine that is also commonly abused. Studies have shown that N2O alters the function of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), GABAA, opioid, and serotonin receptors among others. However, the receptors systems underlying the abuse-related central nervous system effects of N2O are unclear. The present study explores the receptor systems responsible for producing the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O. B6SJLF1/J male mice trained to discriminate 10 minutes of exposure to 60% N2O + 40% oxygen versus 100% oxygen served as subjects. Both the high-affinity NMDA receptor channel blocker (+)-MK-801 maleate [(5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate] and the low-affinity blocker memantine partially mimicked the stimulus effects of N2O. Neither the competitive NMDA antagonist, CGS-19755 (cis-4-[phosphomethyl]-piperidine-2-carboxylic acid), nor the NMDA glycine-site antagonist, L701-324 [7-chloro-4-hydroxy-3-(3-phenoxy)phenyl-2(1H)-quinolinone], produced N2O-like stimulus effects. A range of GABAA agonists and positive modulators, including midazolam, pentobarbital, muscimol, and gaboxadol (4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[4,5-c]pyridine-3-ol), all failed to produce N2O-like stimulus effects. The μ-, κ-, and δ-opioid agonists, as well as 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 1B/2C (5-HT1B/2C) and 5-HT1A agonists, also failed to produce N2O-like stimulus effects. Ethanol partially substituted for N2O. Both (+)-MK-801 and ethanol but not midazolam pretreatment also significantly enhanced the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O. Our results support the hypothesis that the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O are at least partially mediated by NMDA antagonist effects similar to those produced by channel blockers. However, as none of the drugs tested fully mimicked the stimulus effects of N2O, other mechanisms may also be involved.

Introduction

Nitrous oxide gas (N2O), a widely used anesthetic adjunct in dentistry and surgical anesthesia, is subject to widespread abuse (Garland et al., 2009), with as many as 88,000 people aged 12–17 years annually initiating nonmedical recreational use (http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/inhalantTrends/inhalantTrends.htm). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimated in 2005 that 21% of adolescent inhalant abusers first experience using an inhalant was with N2O (http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/inhalantTrends/inhalantTrends.htm). At the present time, the neurotransmitter system or systems responsible for the subjective intoxication produced by N2O are not well understood (Zacny et al., 1994; Beckman et al., 2006), which significantly hampers the development of interventions to treat and prevent N2O abuse.

In vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that N2O modulates the activity of a number of neurotransmitter receptors. A significant body of evidence implicates the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor complex as an important mediator of N2O’s effects. N2O inhibits human NR1A and NR2A NMDA receptor subunits in Xenopus oocytes (Yamakura and Harris, 2000; Ogata et al., 2006). The locomotor incoordinating effects of N2O are reduced in Caenorhabditis elegans, with a nmr-1 gene loss-of-function mutation encoding a NMDA-type glutamate receptor (Nagele et al., 2004). NMDA receptors in rat hippocampal neurons are inhibited in a noncompetitive and voltage-dependent manner by N2O (Jevtović-Todovorić et al., 1998; Mennerick et al., 1998), and NMDA-evoked striatal dopamine release is reduced by N2O (Balon et al., 2003). Finally, N2O alters isoflurane (Petrenko et al., 2010) and sevoflurane (Sato et al., 2005) minimal alveolar concentration in NMDA receptor epsilon-1 subunit gene knockout in mice.

Considerable evidence also implicates GABAA receptors as a mediator of N2O’s effects. N2O potentiates GABAA receptor current in the presence of an agonist, suggesting it may act as a positive allosteric modulator (Hapfelmeier et al., 2000). N2O exposure increases the current flow in GABAA α1β2γ2S and α1β2γ2L receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Hapfelmeier et al., 2000; Yamakura and Harris, 2000). N2O also potentiates the effects of the GABAA agonist muscimol in cultured hippocampal neurons (Dzoljic and Van Duijn, 1998). In mice, the benzodiazepine site antagonist flumazenil and the GABAA competitive antagonist, SR-95531 [6-imino-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1(6H)-pyridazinebutanoic acid hydrobromide], reverse the anxiolytic-like effects of N2O (Czech and Green, 1992; Czech and Quock, 1993; Li and Quock, 2001). Finally, flumazenil reduces ratings of subjective “high” produced by N2O in human subjects (Zacny et al., 1995).

Opioid receptors have been implicated as being involved in the analgesic and antinociceptive properties of N2O. The κ-opioid antagonist nor-binaltorphimine but not the δ-opioid antagonist naltrindole attenuates N2O analgesia (Koyama and Fukuda, 2010). A mixed agonist/antagonist at μ-opioid receptors, β-chlornaltrexamine reverses N2O antinociceptive responses (Emmanouil et al., 2008). However, in humans naloxone does not alter N2O’s subjective or cognitive impairing effects nor N2O-induced changes in pain perception (Zacny et al., 1994, 1999). Lastly, N2O results in release of serotonin in the rat spinal cord (Mukaida et al., 2007), and other data suggest that the anxiolytic and antinociceptive effects of N2O may involve a serotonergic mechanism (Mueller and Quock, 1992; Emmanouil, et al., 2006).

Taken together these studies suggest that the pharmacologic properties of N2O are complex and that different receptor systems may be involved depending on the response that is being examined. It is presently unclear which, if any, of these receptor systems are responsible for the abuse-related subjective effects of N2O. We sought to address that question by use of the drug-discrimination procedure in mice. Drug discrimination models human subjective intoxication and is an extremely powerful behavioral research tool for examining the receptor mechanisms underlying abuse-related behavioral effects of drugs (Colpaert, 1999). We have previously demonstrated that 10 minutes of exposure to 60% N2O can be trained as a discriminative stimulus in mice (Richardson and Shelton, 2014). Our data showed that N2O shares discriminative stimulus effects with toluene, but there is little overlap between the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O and other abused inhalants and vapor anesthetics. In the present study, we examined the role of NMDA, GABAA, opioid, and serotonin receptors in transducing the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

Twenty-four adult male B6SJLF1/J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) served as subjects. These mice had previously been used in a study designed to determine whether it was possible to train a discrimination based on inhaled N2O (Richardson and Shelton 2014). The mice were maintained at 85% of their free-feed body weights by regulating food intake to 2–5 g of standard rodent chow per day (Harlan, Teklad, Madison, WI) after training. Water was available ad libitum except during experimental sessions. All subjects were individually housed in 31.5 cm × 19.5 cm clear polycarbonate cages with corncob bedding (Teklad, Madison, WI) on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on 6:00 AM) in a colony room maintained at 77°F with 44% humidity. Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University and conducted in accordance with the Institute of Laboratory Animal Research Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011).

Apparatus.

Exposures to oxygen and N2O/oxygen gas mixtures were conducted in one of four 26-l acrylic exposure cubicles that encased modified two-lever mouse operant conditioning chambers (model ENV-307AW; MED Associates, St. Albans, VT). Two yellow light-emitting diode stimulus lights, two response levers, and a liquid dipper were located on the front wall of each chamber. A single 5-watt light-emitting diode house light was located at the top center of the chamber rear wall. The drug-discrimination schedule conditions and data recordings were controlled by a MED Associates interface and MED-PC version 4 software (MED Associates). The milk solution used as a reinforcer consisted of 25% sugar, 25% nonfat powdered milk, and 50% tap water by volume.

N2O and oxygen exposure mixtures were controlled by a manually operated gas metering system. Briefly, an Airsep Onyx+ oxygen concentrator (Buffalo, NY) generated ≥98% oxygen. N2O gas was supplied by a compressed N2O cylinder and a single-stage regulator. The N2O and O2 flow rates were regulated by individual rotameters, and the individual gas streams were combined before passing into the inhalant exposure chamber. System components were connected with Tygon tubing (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). Waste gas was expelled into a fume hood.

Drugs.

Medical grade N2O gas cylinders were obtained from National Welders Supply (Richmond, VA). Memantine, CGS-19755 (cis-4-[phosphomethyl]-piperidine-2-carboxylic acid), muscimol, U50-488H [trans-(±)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)cyclohexyl]benzeneacetamide hydrochloride], 8-OH DPAT [(±)-8-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin hydrobromide], and mCPP [1-(3-chlorophenyl)piperazine hydrochloride] were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (St. Louis, MO). Pentobarbital, valproic acid, gaboxadol (4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[4,5-c]pyridine-3-ol), and (+)-MK-801 maleate [(5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate] were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Midazolam HCL was purchased from the VCU hospital pharmacy. Ethanol (95% weight/volume) was obtained from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). Morphine sulfate and L-701,324 [7-chloro-4-hydroxy-3-(3-phenoxy)phenyl-2(1H)-quinolinone] were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse drug supply program (Bethesda, MD). The SNC-80 [(+)-4-[(αR)-α-((2S,5R)-4-allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide] was generously provided by Kenner Rice at the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD).

The vehicle for SNC-80 was 0.9% saline, pH adjusted to between 6.0 and 7.0. L-701,324 was solubilized in 10% Cremophor in sterile water. All other injected compounds were prepared in 0.9% sterile saline. All drugs except ethanol were prepared to achieve a constant injection volume of 10 ml/kg. To prevent tissue damage, ethanol doses higher than 1000 mg/kg were produced by increasing injection volumes of a 100-mg/ml ethanol solution. Morphine sulfate was administered subcutaneously. All other injected compounds were administered intraperitoneally. SNC-80, memantine, muscimol, gaboxadol, CGS 19755, L-701,324, and U50-488H were administered 30 minutes before testing. The mCPP was administered 20 minutes before testing. All other injected drugs were administered 10 minutes before testing. N2O exposures were begun 10 minutes before the start of and continued for the duration of the operant test session. All drug doses are expressed as their salt weight.

Training, Acquisition, and Substitution Test Procedure.

Subjects were previously trained to discriminate a 10-minute exposure to 60% N2O + 40% O2 mixture from 100% O2 in once daily (Monday–Friday) milk-reinforced 5-minute operant sessions (Richardson and Shelton, 2014). In our present study, training sessions continued on Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday. Substitution test sessions were conducted each Tuesday and Friday. Briefly, the first 10 minutes of each training session was a time-out in which the animals were placed into the operant chambers and gas delivery was initiated. After 10 minutes of exposure, the house and lever lights were illuminated, and a 5-minute operant session commenced.

During the operant session, completion of a fixed-ratio 12 (FR12) response requirement on the active lever resulted in 3 seconds of access to a 0.01-ml milk dipper. Responding on the inactive lever reset the FR requirement on the correct lever. N2O and O2 vehicle training sessions were presented in a double alternation sequence across training days. Subjects were eligible to test if they maintained accurate stimulus control on training sessions between tests. Specifically, the subject must have emitted their first complete FR12 on the correct lever and a minimum 80% of total lever presses on the correct lever in all of the training sessions since the last test session. If an animal failed to maintain this level of performance, the double alternation training schedule was continued until the subject met the daily accuracy criteria for three consecutive days.

On test days, both levers were active, and completion of the FR12 requirement on either lever was reinforced. Generally, substitution concentration–effect or dose–effect curves were examined in ascending dose order and were preceded by 100% O2 and 60% N2O + 40% O2 control test sessions. When the test drug was an injected compound, both the O2 and N2O control test exposures were preceded by vehicle injections. When possible, doses were increased until maximal substitution was apparent or a test condition resulted in a greater than 50% mean suppression of responding compared with the O2 control.

Data Collection and Analysis.

The dependent measures collected were the percentage of N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.), the operant response rate (± S.E.M.), and the lever upon which the first fixed ratio was completed. Mean N2O-lever appropriate responding of less than 20% was defined as no substitution, 21%–79% as partial substitution, and 80%–100% as full substitution. Suppression of operant responding produced by each drug was examined by one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Geisser-Greenhouse corrections for sphericity. Significant main effects were followed by Dunnett post hoc tests comparing each dose to its vehicle control. Statistical analysis examining percentage N2O–lever selection resulting from combining N2O with MK-801, ethanol, and midazolam was by two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

To accommodate missing data due to the failure of some subjects at high-dose combinations to emit sufficient responses to generate a lever-selection value, each curve combining a single dose of pretreatment drug with increasing N2O concentrations was separately compared with the control curve combining N2O with vehicle. Only those dose combinations in which all subjects emitted at least one complete fixed ratio value were included in the analysis. Subsequent analyses of significant interactions were by Sidak post hoc tests.

Statistical analysis examining the response rate alterations resulting from combining N2O with MK-801, ethanol, and midazolam were by two-way repeated measures ANOVA comparing all N2O + drug pretreatment conditions. Subsequent analyses of significant interactions were by Sidak post hoc tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. All ANOVA and post hoc tests were performed using Prism version 6.0 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

In addition, when possible, confidence limits (CL), potencies, and half-maximal effective concentrations or doses (EC50 or ED50) of the percentage of N2O-lever responding and suppression of operant response rates were calculated using values on the linear portion of each mean dose-effect curve using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) based on published methods (Bliss, 1967; Tallarida and Murray, 1987).

Results

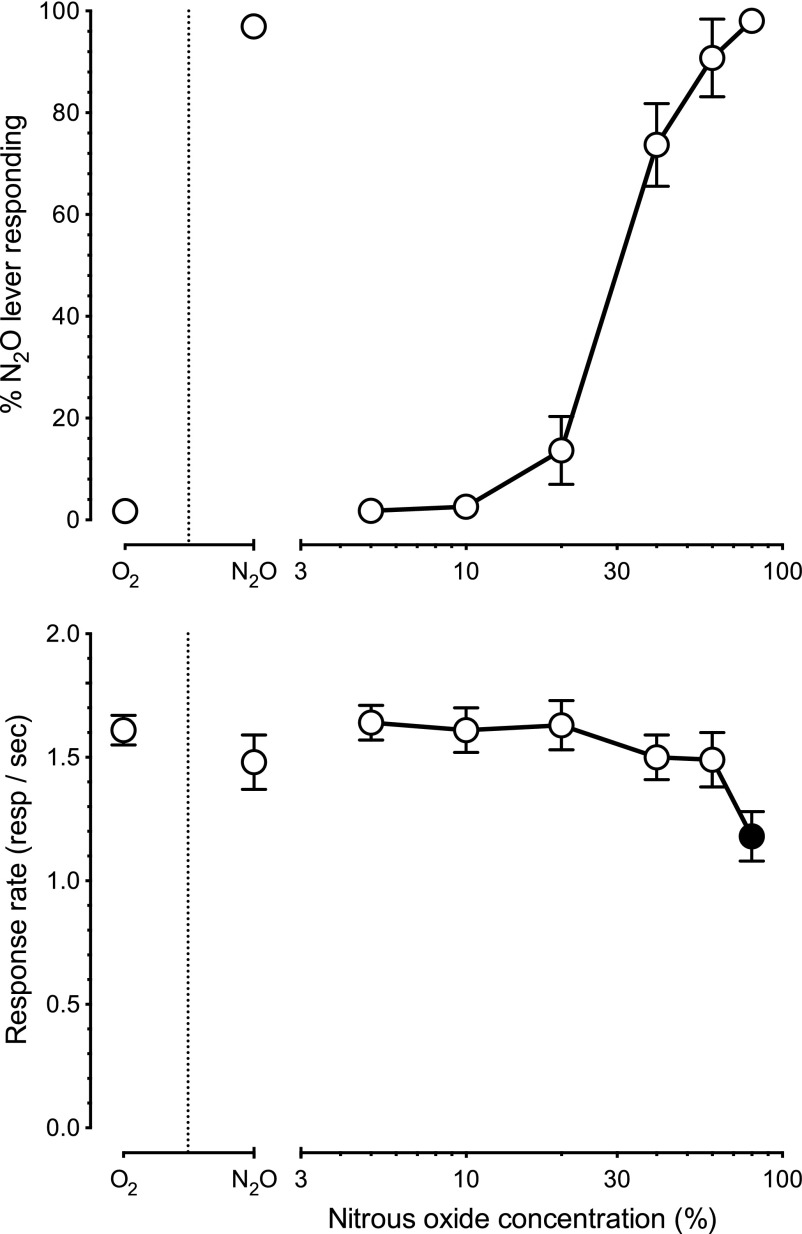

N2O (n = 24) produced concentration-dependent full substitution for the 60% training concentration with an EC50 of 33% (CL: 29%–37%) (Fig. 1, upper panel). Control tests of 100% O2 and 60% N2O + 40% O2 produced a mean of 2% (±1) and 97% (±1) N2O lever-selection, respectively. Full substitution was produced by both 60% and 80% N2O. There was a main effect of N2O concentration on operant responding [F(2.5,56.5) = 15.0, P < 0.01] but only 80% N2O (Fig. 1, lower panel, filled symbol) significantly (P < 0.05) attenuated operant responding below the O2 control response rates.

Fig. 1.

Mean percentage N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) shown in the upper panel and operant response rates shown in the lower panel for 24 mice trained to discriminate 10 minutes of exposure to 60% N2O + 40% oxygen from 100% oxygen. Points above O2 and N2O reflect the 100% oxygen and 60% N2O + 40% oxygen control conditions. Filled symbols in the lower panel indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) suppression of response rates relative to the oxygen control condition.

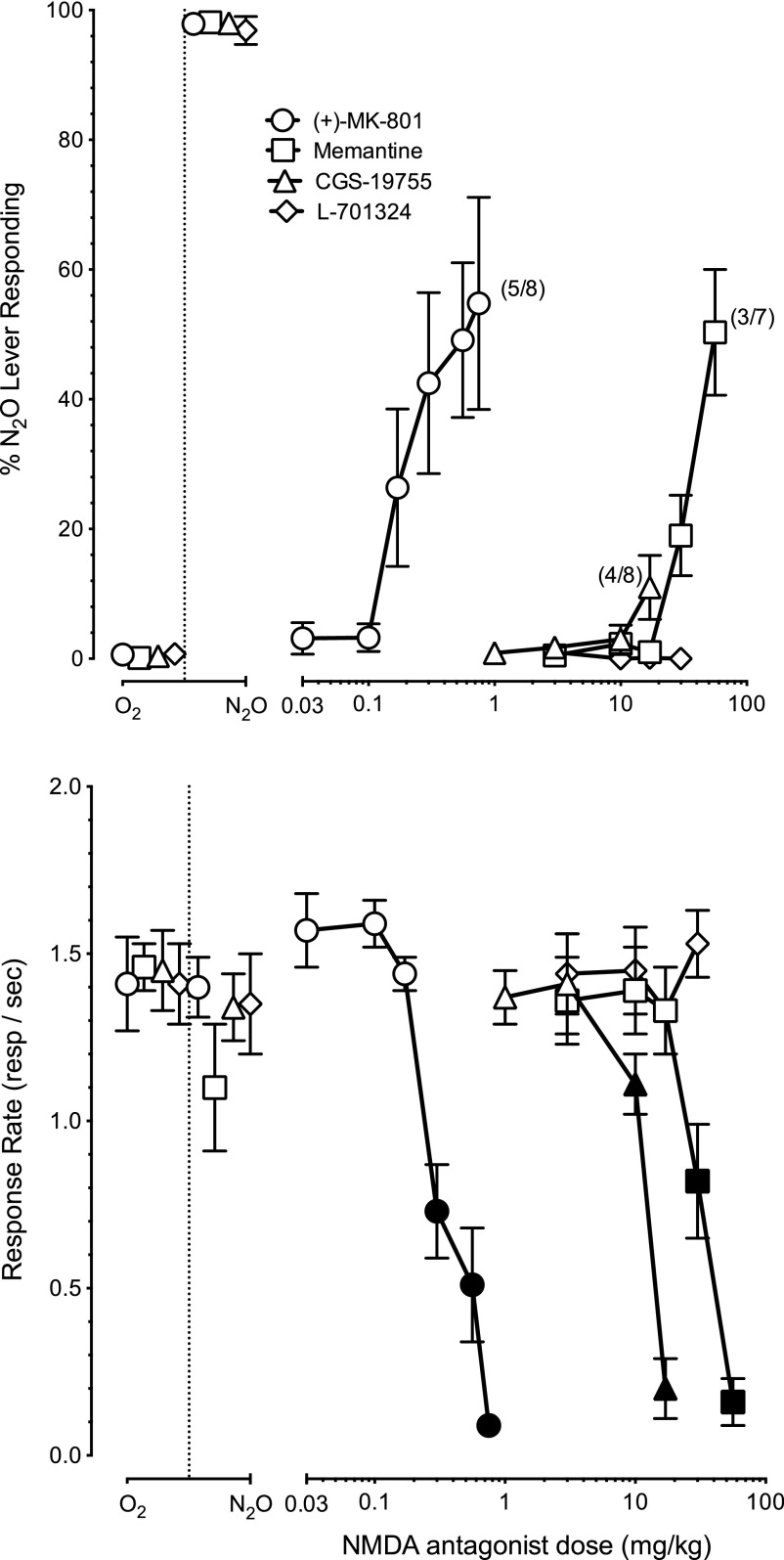

The high-affinity NMDA receptor channel blocker (+)-MK-801 (n = 8) produced dose-dependent partial substitution for 60% N2O (Fig. 2, upper panel, ○) with an ED50 of 0.39 mg/kg (CL: 0.20–0.77 mg/kg). Maximum mean N2O-lever selection of 55% (±16) was produced by a dose of 0.75 mg/kg (+)-MK-801. In addition, (+)-MK-801 (Fig. 2, lower panel, ○) attenuated operant responding with an ED50 of 0.39 mg/kg (CL: 0.30–0.50 mg/kg). There was a main effect of (+)-MK-801 dose on operant responding [F(2.4,16.4) = 30.6, P < 0.01] with suppression of responding (P < 0.05) at doses of 0.30–0.75 mg/kg (●).

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) shown in the upper panel and operant response rates (± S.E.M.) shown in the lower panel produced by (+)-MK-801 (n = 8) [○], memantine (n = 7) [□], CGS-19755 (n = 8) [▵], and L-701,324 (n = 7) [⋄] in mice trained to discriminate N2O from oxygen. Points above O2 and N2O reflect the 100% oxygen and 60% N2O + 40% oxygen control conditions. Numbers in brackets indicates the number of subjects that earned at least one reinforcer (first value) and the total number of subjects tested at that dose (second value). Filled symbols in the lower panel indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) suppression of response rates relative to the oxygen control condition.

The low-affinity NMDA receptor channel blocker memantine (n = 7) produced a maximum of 50% (±10) N2O-lever responding at a dose of 56 mg/kg (Fig. 2, upper panel, □). Memantine (Fig. 2, lower panel) also dose dependently [F(2.3, 14) = 24.16, P < 0.01] attenuated operant responding with an ED50 of 29.2 mg/kg (CL: 24.9–34.3 mg/kg). Operant responding relative to vehicle was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) by memantine doses of 30 and 56 mg/kg (▪).

The competitive NMDA antagonist CGS-19755 (n = 8) failed to substitute for 60% N2O (Fig. 2, upper panel, ▵). CGS-19755 (Fig. 2, lower panel, ▵) attenuated operant responding [F(2.5,17.5) = 40.8, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 12.0 mg/kg (CL: 8.1–17.9 mg/kg). Post hoc analysis indicated that responding was suppressed at doses of 10 and 17 mg/kg (P < 0.05, ▴). The NMDA receptor glycine site antagonist L-701,324 (n = 7) also failed to substitute for N2O, producing no greater than 1% N2O-lever selection at any dose (Fig. 2, upper panel, ⋄). L-701,324 (Fig. 2, lower panel, ⋄) failed to attenuate operant responding [F(2.5,17.5) < 1, P = 0.44] up to the maximum dose tested of 30 mg/kg.

Figure 3 shows the substitution concentration-effect curves (upper panel) and response rate effects (lower panel) produced by increasing concentrations of N2O after pretreatment with vehicle, or 0.03 or 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 (n = 7). The EC50 of N2O + vehicle (Fig. 3, ○) was 32% (CL: 25%–41%). Pretreatment with 0.03 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 (□) resulted in a N2O EC50 of 26% (CL: 17%–39%). Pretreatment with 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 (▵) produced a more pronounced 1.9-fold leftward shift in the N2O lever-selection curve, further reducing the EC50 of N2O to 17% (CL: 13%–23%). There was no statistically significant main effect of 0.03 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 treatment [F(1,6) = 2.2, P = 0.19], nor was there an interaction between 0.03 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 treatment and N2O exposure concentration [F(4,24) = 1.2, P = 0.33] on the percentage of N2O lever selection. There was a main effect of 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 treatment [F(1,6) = 7.9, P = 0.03] as well as an interaction between the 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 treatment dose and N2O exposure concentration [F(3,18) = 4.9, P = 0.01] on the percentage of N2O lever selection. Post hoc tests revealed that pretreatment with 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 enhanced (t = 4.6, P < 0.05) the discriminative stimulus effects of 20% N2O over that produced by N2O alone (upper panel, filled symbol). There was also both a main effect [F(2,12) = 13.6, P < 0.01] of (+)-MK-801 pretreatment dose as well as an interaction [F(8,48) = 6.5, P < 0.01] of the (+)-MK-801 pretreatment dose and N2O concentration on operant response rates. Post hoc tests revealed that 40% + 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 (t = 4.9) and 60% N2O + 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 (t = 9.8) resulted in a greater (P < 0.05) operant response rate suppression than 40% or 60% N2O alone (lower panel, filled symbols).

Fig. 3.

Mean percentage N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) shown in upper panel and operant response rates (± S.E.M.) shown in the lower panel after pretreatment with vehicle [○], 0.03 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 [□], or 0.17 mg/kg (+)-MK-801 [▵] before 10 minutes of exposure to increasing concentrations of N2O (n = 7). Points above O2 and N2O reflect the 100% oxygen and 60% N2O + 40% oxygen control conditions. Filled symbols in the upper and lower panels indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences from the corresponding N2O + vehicle control values.

Table 1 shows the results of substitution testing with GABAA receptor agonists and positive modulators. Gaboxadol (n = 8), a GABAA receptor agonist selective for δ-subunit–containing extrasynaptic receptors resulted in a maximum of 4% (±3) N2O-lever responding at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg. Gaboxadol attenuated operant responding [F(2.4,17.1) = 105, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 6.4 mg/kg (CL: 2.6–15.7 mg/kg). The synaptic GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (n = 8) produced a maximum of 22% (±22) N2O-lever responding at a dose of 1.7 mg/kg. Muscimol dose-dependently attenuated operant response rates [F(1.5,10.4) = 32.4, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 1.2 mg/kg (CL: 0.9–1.6 mg/kg).

TABLE 1.

Percentage of N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) and responses per second (± S.E.M.) produced by gaboxadol, muscimol, valproic acid, midazolam, and pentobarbital

Values in [brackets] indicate the number of subjects earning at least one reinforcer (first value) and subjects tested (second value).

| Test Drug | Drug Dose | Percentage of N2O Lever Responding (± S.E.M.) | Response Rate in Responses per Second (± S.E.M.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | |||

| Gaboxadol (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 0.0 (0.0) | 1.4 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 99.4 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.1) | |

| 0.3 | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 3.9 (2.6) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 3 | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | |

| 10 | — | 0.0 (0.0)* | |

| Muscimol (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 0.6 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 96.4 (2.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | |

| 0.3 | 1.0 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | |

| 1.7 | 21.8 (21.8) [4/8] | 0.6 (0.3)* | |

| 3 | — | 0.0 (0.0)* | |

| Valproic acid (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 95.8 (2.3) | 1.2 (0.2) | |

| 100 | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 300 | 2.3 (2.3) | 1.3 (0.1) | |

| 560 | 33.0 (14.8) [4/8] | 0.4 (0.2)* | |

| Midazolam (n = 9) | O2 + vehicle | 2.1 (1.7) | 1.4 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 98.4 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 4.9 (1.6) | 1.2 (0.1) | |

| 3 | 4.4 (3.5) | 1.3 (0.1) | |

| 10 | 11.3 (4.8) [8/9] | 0.6 (0.1)* | |

| 17 | 19.7 (8.7) | 0.5 (0.1)* | |

| 30 | 16.2 (9.1) | 0.6 (0.1)* | |

| 56 | 27.3 (7.2) | 0.5 (0.1)* | |

| Pentobarbital (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 95.8 (2.0) | 1.1 (0.2) | |

| 3 | 8.3 (6.5) | 1.4 (0.2) | |

| 10 | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 17 | 1.8 (1.2) | 1.5 (0.1) | |

| 30 | 9.5 (3.4) | 1.0 (0.1)* | |

| 50 | — | 0.2 (0.1)* |

Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference in response rates compared with the oxygen + vehicle control condition.

The anticonvulsant valproic acid, which inhibits GABA transaminase, produced a maximum of 33% (±15) N2O-lever responding. Valproic acid (n = 8) dose-dependently suppressed operant responding [F(2,14) = 27.6, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 430 mg/kg (CL: 384–481 mg/kg). The GABAA receptor benzodiazepine-site positive allosteric modulator midazolam (n = 9) produced a maximum of 27% (±7) N2O-lever responding. Midazolam dose-dependently attenuated operant responding [F(3.2,25.8) = 26.4, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 10.5 mg/kg (CL: 3.2–34.8 mg/kg). The GABAA receptor barbiturate-site positive allosteric modulator pentobarbital (n = 8) produced a maximum of 10% (±3) N2O-lever responding. Pentobarbital dose-dependently suppressed operant responding [F(2.9,20.2) = 26.2, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 28.9 mg/kg (CL: 17–49 mg/kg).

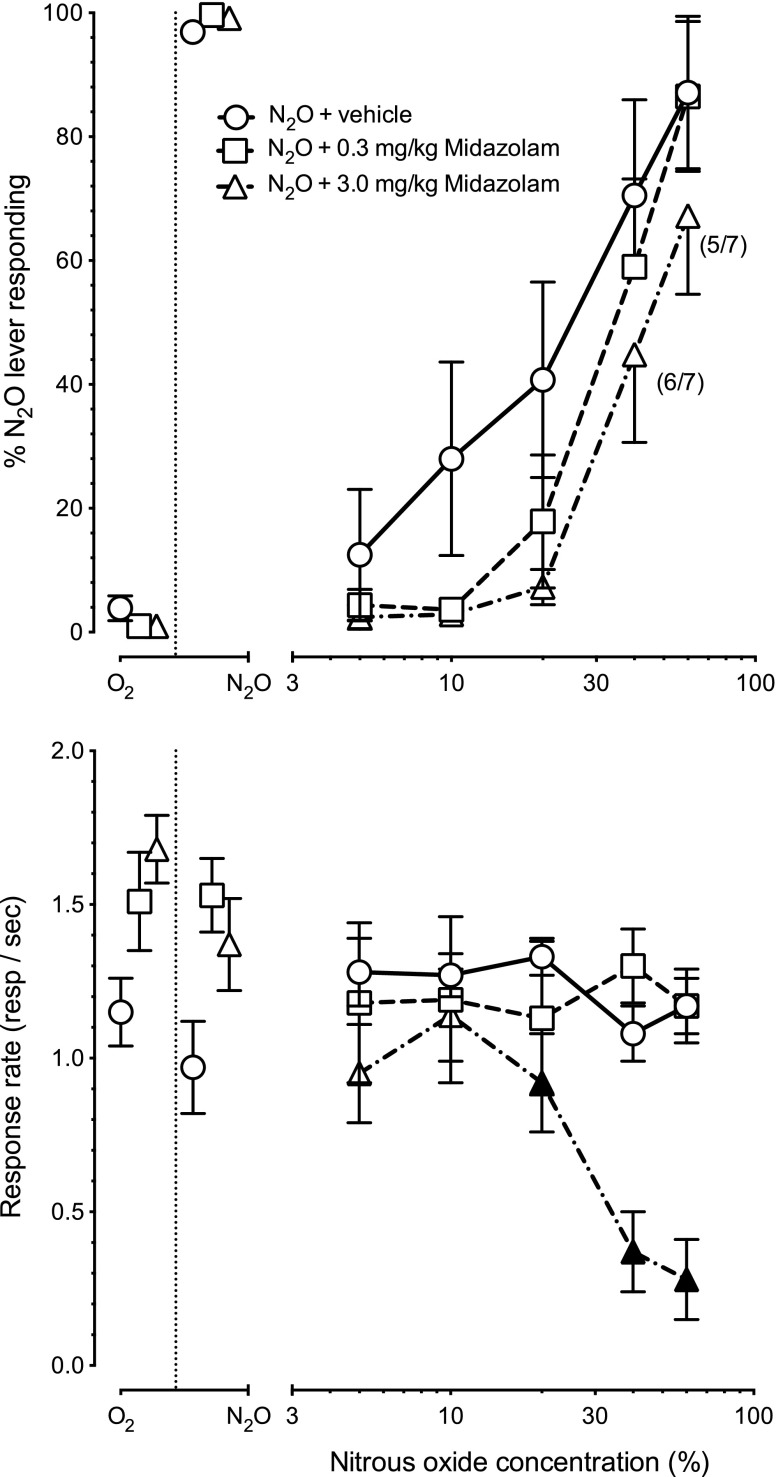

Figure 4 shows the results of pretreatment with vehicle, or 0.3 or 3 mg/kg i.p. midazolam before exposure to increasing concentrations of N2O (n = 8). The upper panel depicts N2O-lever selection and the lower panel the operant response rates. Vehicle administration before N2O exposure produced a N2O-lever selection EC50 of 25% (CL: 14%–44%). N2O combined with 0.3 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg midazolam produced N2O-lever selection EC50’s of 35% (CL: 25%–47%) and 44% (CL: 35%–56%), respectively. There was no main effect [F(1,7) = 1.6, P = 0.25] or interaction [F(4,28) < 1, P = 0.81] of 0.3 mg/kg midazolam pretreatment on N2O-lever selection.

Fig. 4.

Mean percentage N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) shown in upper panel and operant response rates (± S.E.M.) shown in the lower panel after pretreatment with vehicle [○], 0.3 mg/kg midazolam [□], or 3.0 mg/kg midazolam [▵] before 10 minutes of exposure to increasing concentrations of N2O (n = 8). Numbers in brackets indicates the number of subjects that earned at least one reinforcer (first value) and the total number of subjects tested at that dose (second value). Filled symbols in the lower panel indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) suppression of response rates from the corresponding N2O + vehicle control values.

Analysis of variance was not performed on lever selection data generated when combining 3 mg/kg midazolam + N2O because of missing data resulting from complete suppression of responding in some subjects in the higher dose-combination conditions. There was both a main effect of midazolam pretreatment dose [F(2,14) = 6.6, P < 0.01] as well as an interaction of midazolam pretreatment dose and N2O concentration [F(8,56) = 4.5, P < 0.01] on operant rate suppression (Fig. 4, lower panel). Post hoc analysis showed that 3 mg/kg of midazolam enhanced (P < 0.05) the response-rate suppression produced by concentrations of 20%–60% N2O (▴).

Table 2 shows the results of substitution testing with opioid receptor agonists, ethanol, and selected serotonergic agonists. The μ-opioid receptor agonist morphine (n = 8) produced a maximum of 33% (±33) N2O-lever responding at the highest test dose of 30 mg/kg. Morphine dose-dependently attenuated operant responding [F(2.5,17.9) = 39.13, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 7.9 mg/kg (CL 3.9–16.2 mg/kg). The κ-opioid receptor agonist U50-488H (n = 8) produced a maximum of 11% (±11) N2O-lever responding at a dose of 7 mg/kg. U50-488H dose-dependently reduced operant response rates [F(1.4,9.7) = 32.4, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 3.3 mg/kg (CL: 2.7–4.1 mg/kg). The δ opioid receptor agonist SNC-80 (n = 8) produced a maximum of 10% N2O-lever responding. SNC-80 dose-dependently attenuated operant responding [F(2.3,16.0) = 13.7, P < 0.01] with an ED50 of 28.6 mg/kg (CL: 16.8–48.6 mg/kg).

TABLE 2.

Percentage of N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) and response rate (± S.E.M.) produced by morphine, U-50488H, SNC-80, ethanol, mCPP, and 8-OH-DPAT

Values in [brackets] indicate number of subjects earning at least one reinforcer (first value) and subjects tested (second value).

| Test Drug | Drug Dose | Percentage of N2O Lever Responding (± S.E.M.) | Response Rate in Responses per Second (± S.E.M.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | |||

| Morphine (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 2.4 (1.6) | 1.8 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 96.1 (2.5) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 2.4 (1.6) | 1.7 (0.1) | |

| 3 | 15.1 (12.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | |

| 10 | 3.3 (2.2) | 0.9 (0.2)* | |

| 30 | 33.3 (33.3) [3/8] | 0.1 (0.0)* | |

| U-50488H (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 2.4 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 95.8 (2.4) | 1.3 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 2.4 (1.6) | 1.7 (0.1) | |

| 3.2 | 1.6 (1.6) [5/8] | 0.9 (0.3)* | |

| 7 | 10.7 (10.7) [3/8] | 0.1 (0.1)* | |

| SNC-80 (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 93.0 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.2) | |

| 1 | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.1) | |

| 10 | 10.3 (2.9) | 1.2 (0.1)* | |

| 17 | 7.9 (3.0) | 1.1 (0.2)* | |

| 30 | 8.7 (1.8) [7/8] | 0.8 (0.2)* | |

| 56 | 6.8 (1.8) [5/8] | 0.5 (0.2)* | |

| Ethanol (n = 9) | O2 + vehicle | 2.3 (1.5) | 1.6 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 96.6 (1.5) | 1.3 (0.2) | |

| 1000 | 9.6 (6.6) | 1.4 (0.1)* | |

| 1500 | 11.6 (5.5) | 1.3 (0.1)* | |

| 2000 | 44.9 (15.3) | 0.8 (0.1)* | |

| 2500 | 55.0 (13.2) | 0.4 (0.1)* | |

| mCPP (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 2.6 (1.7) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 96.9 (1.7) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 0.1 | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | |

| 1 | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.6 (0.1) | |

| 5.6 | 3.4 (1.7) | 0.9 (0.2)* | |

| 10 | 20.6 (17.0) [5/8] | 0.4 (0.2)* | |

| 8-OH DPAT (n = 8) | O2 + vehicle | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.6 (0.1) |

| N2O + vehicle | 98.3 (1.5) | 1.5 (0.1) | |

| 0.1 | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.4 (0.1) | |

| 0.3 | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.1)* | |

| 1 | 1.1 (1.1) [7/8] | 0.5 (0.1)* | |

| 1.56 | 4.3 (2.4) [6/8] | 0.4 (0.1)* |

Statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference in response rates compared with the oxygen + vehicle control condition.

Ethanol (n = 9) elicited a maximum of 55% (±13) N2O-lever responding at the highest test dose of 2500 mg/kg. The substitution ED50 of ethanol for N2O was 2238 mg/kg (CL: 1397–3587 mg/kg). Ethanol dose-dependently attenuated operant response rates [F(1.8,14) = 34.7, P<0.01] with an ED50 of 2109 mg/kg (CL: 1909–2332 mg/kg).

The 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 1B/2C (5-HT1B/2C) receptor agonist mCPP produced a maximum of 21% (±17) N2O-lever responding at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Also, mCPP (n = 8) dose-dependently attenuated operant responding with an ED50 of 3.7 mg/kg (CL 2.2–6.5 mg/kg) and suppressed operant responding at doses of 5.6 and 10 mg/kg [F(2.2,15.4) = 25.5, P < 0.01]. The 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH DPAT (n = 8) produced no greater than 4% N2O-lever selection at any dose; 8-OH DPAT dose-dependently attenuated operant responding with an ED50 of 0.5 mg/kg (CL: 0.38–0.71 mg/kg) and suppressed operant responding [F(2.3,15.8) = 31.4, P < 0.01] at doses of 0.3–1.56 mg/kg.

Figure 5 shows the effect of pretreatment with either 500 or 1500 mg/kg i.p. ethanol before exposure to increasing concentrations of N2O. The upper panel depicts N2O-lever selection and the lower panel the operant response rates. Vehicle pretreatment before N2O exposure (Fig. 5, upper panel, ○) resulted in a N2O-lever selection EC50 of 31% (CL: 27–36%). Pretreatment with a low dose of 500 mg/kg ethanol (Fig. 5, upper panel, □) resulted in a N2O-lever selection EC50 of 27% (CL: 23%–32%). Pretreatment with a higher dose of 1500 mg/kg ethanol (Fig. 5, upper panel, ▵) produced a 2.8-fold leftward shift in the N2O substitution concentration effect curve and a N2O-lever selection EC50 of 11% (CL: 7%–18%).

Fig. 5.

Mean percentage N2O lever responding (± S.E.M.) shown in upper panel and operant response rates (± S.E.M.) shown in the lower panel after pretreatment with vehicle [○], 500 mg/kg ethanol [□], or 1500 mg/kg ethanol [▵] before 10 minutes of exposure to increasing concentrations of N2O (n = 8). Points above O2 and N2O reflect the 100% oxygen and 60% N2O + 40% oxygen control conditions. Filled symbols in the upper and lower panels indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences from the corresponding N2O + vehicle control values.

There was no main effect [F(1,7) = 1.5, P = 0.3] or interaction [F(4,28) < 1, P = 0.51] between the 500 mg/kg ethanol pretreatment dose and N2O concentration on the percentage N2O-lever selection. However, there was a main effect [F(1,7) = 19.8, P < 0.01] as well as an interaction [F(3,21) = 3.9, P = 0.02] between the 1500 mg/kg ethanol pretreatment dose and N2O concentration on the percentage of N2O-lever selection. Post hoc analysis revealed that pretreatment with 1500 mg/kg ethanol enhanced (t = 5.6, P < 0.05) the discriminative stimulus effects of 20% N2O (Fig. 5, upper panel, ▴). There was a main effect of ethanol pretreatment dose [F(2,14) = 21.1, P < 0.01] as well as an interaction [F(8,56) = 4.1, P < 0.01] of ethanol pretreatment dose and N2O concentration on rates of operant responding (Fig. 5, lower panel). Post hoc analysis revealed that 1500 mg/kg ethanol suppressed (P < 0.05) operant responding at the 5% (t = 3.9), 10% (t = 2.7), 20%, (t = 6.4), and 60% (t = 9.4) N2O concentrations (Fig. 5, lower panel, ▴). Pretreatment with a lower dose of 500 mg/kg ethanol only enhanced (t = 2.4, P < 0.05) the operant response rate suppressing effects of 60% N2O. (Fig. 5, lower panel, ▪).

Discussion

The overarching goal of the present study was to explore the receptor mechanisms underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O. Given the strong in vitro evidence that N2O attenuates NMDA receptor function (Jevtović-Todovorić et al., 1998; Mennerick et al., 1998; Yamakura and Harris, 2000; Balon et al., 2003; Nagele et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2005; Ogata et al., 2006; Petrenko et al., 2010), a number of site-selective NMDA antagonists were tested for their ability to substitute for N2O (Fig. 2). Neither the competitive NMDA antagonist CGS-19755 nor the NMDA receptor glycine site antagonist L-710,324 produced appreciable substitution for N2O. However, doses up to 30 mg/kg of L-701,324 also failed to suppress operant responding. It is therefore possible that an adequate dose range of L-701,324 was not tested, but this seems unlikely given a report showing that 10 mg/kg of L-701,324 has behavioral effects in other rodent discrimination procedures (Nicholson and Balster, 2009) and doses lower than 10 mg/kg have other behavioral effects in rodents (Poleszak et al., 2011; Wlaz and Poleszak, 2011). In contrast, the high-affinity NMDA receptor channel blocker (+)-MK-801 produced 55% N2O-lever responding, suggesting a possible channel blocker-like effect of N2O.

To systematically replicate this finding, we also tested the low-affinity NMDA receptor channel blocker memantine, which produced a comparable level of 50% N2O-lever responding. The latter result not only confirmed the findings with (+)-MK-801 but also suggests that the relative affinity of NMDA receptor channel blockers is not critical for modulating N2O-like stimulus effects.

Although the data with (+)-MK-801 and memantine suggest that N2O may have channel blocker–like stimulus effects, the degree of substitution produced by both drugs was incomplete and could be due to drug effects unrelated to their subjective stimulus properties. For instance, NMDA antagonists disrupt glutamatergic neurotransmission in long-term potentiation (Manahan-Vaughan et al., 2008), which can interrupt memory recall (Florian and Roullet, 2004). A disruption of stimulus control could potentially result in levels of N2O-lever selection in the range of 50%, which is that which would be expected if the animals were responding randomly on both levers. However, (+)-MK-801 (Sanger and Zivkovic, 1989; Shelton and Balster, 2004) and other channel blockers (Bowen et al., 1999; Beardsley et al., 2002; Nicholson and Balster, 2003, 2009) are easily trained in drug-discrimination procedures. Further, if a simple disruption of performance were responsible for the present data, one might have also expected partial substitution with the competitive NMDA antagonist CGS-19755 rather than a complete failure of GCS-19755 to substitute for N2O.

A more plausible alternative explanation for the partial substitution produced by (+)-MK-801 and memantine is insufficient specificity of the drug-discrimination assay. This hypothesis is based on data showing that under some conditions NMDA channel blockers will generate intermediate levels of substitution in rodents trained to discriminate stimulants, central nervous system depressants, and serotonergics (Koek et al., 1995). The converse is also true in that benzodiazepines have been demonstrated to produce partial substitution in mice trained to discriminate (+)-MK-801 from vehicle (Shelton and Balster, 2004). To address whether the partial substitution produced by (+)-MK-801 was due to nonspecific effects, we examined whether pretreatment with (+)-MK-801 at doses that produced little or no substitution for N2O when administered alone would alter the discriminative stimulus properties of N2O (Fig. 3). Our hypothesis was that low doses of (+)-MK-801 would only enhance the stimulus effects of N2O if they were acting through a similar mechanism. Indeed, if (+)-MK-801 simply disordered behavior, it might be expected to produce a net antagonism of N2O’s stimulus effects at the higher N2O test concentrations. The results showing that (+)-MK-801 produced an orderly and significant enhancement of the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O support our hypothesis that the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O has a NMDA channel blocker-like component.

Because NMDA antagonists produced incomplete substitution for the training condition, it seems likely that another mechanism also contributes to the stimulus effects of N2O. To examine a potential GABAergic contribution to the stimulus effects of N2O, five site-selective GABA-positive drugs were tested for their ability to substitute for N2O (Table 1). Of the potential GABAergic mechanisms that might have played a role in the stimulus effects of N2O, positive allosteric modulation was most strongly implicated in the literature (Quock et al., 1992; Zacny et al., 1995; Hapfelmeier et al., 2000). However, neither the classic benzodiazepine-site positive allosteric modulator midazolam nor the barbiturate pentobarbital produced meaningful levels of substitution for N2O. Further, midazolam pretreatment failed to significantly enhance the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O, instead producing a trend toward diminishing the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O (Fig. 4). Likewise, neither the extrasynaptic GABAA receptor agonist gaboxadol nor the synaptic GABAA agonist muscimol were N2O-like. Lastly, the relatively nonselective GABA transaminase inhibitor valproic acid produced a low level of partial substitution for N2O, but only at doses that completely suppressed operant responding in four of eight test subjects.

Opioid receptors have been suggested to be involved in the analgesic and antinociceptive effects of N2O (Emmanouil et al., 2008). However, μ-, κ-, and δ-opioid receptors agonists all failed to produce greater than vehicle appropriate responding in N2O-trained mice (Table 2). The poor substitution produced by μ-opioid agonist morphine is consistent with data showing that the opioid antagonist naloxone does not attenuate the subjective effects of 30% N2O in humans (Zacny et al., 1994, 1999). Likewise, the failure of the δ-opioid agonist SNC-80 to substitute for N2O is consistent with reports that the δ-opioid receptor agonist naltrindole does not attenuate N2O analgesia (Koyama and Fukuda, 2010). Our data showing that the selective κ-opioid agonist U50-488H does not substitute for N2O is, however, in conflict with a previous study in which N2O generalized to the purported κ-opioid agonist ethylketocyclazocine in guinea pigs trained to discriminate ethylketocyclazocine from vehicle (Hynes and Hymson, 1984). More recent data have suggested that ethylketocyclazocine is a mixed μ-/κ-opioid agonist and that some of the discriminative stimulus effects of ethylketocyclazocine may result from μ-opioid receptor actions (Wessinger et al., 2011); however, this does not entirely reconcile the prior finding with our present data. It is possible that the differences between studies were the result of species or methods. Additional work will be necessary to resolve this conflict, but based on our present data it does not appear that N2O has opioid-like discriminative stimulus properties under our training conditions.

A number of studies suggest a relationship between the behavioral effect of N2O and ethanol. For instance, N2O reduces 10% ethanol consumption in alcohol-preferring and heavy-drinking strains of rats (Kosobud et al., 2006). Although alcohol drinking before N2O exposure does not appear to augment the subjective effects of N2O (Walker and Zacny, 2001), N2O is chosen more frequently by moderate alcohol drinkers than light drinkers (Zacny et al., 2008). Most recently, our laboratory reported that ethanol produces partial substitution in mice trained to discriminate N2O from vehicle (Richardson and Shelton, 2014). In our present study, we systematically replicated and expanded our prior results by demonstrating not only that ethanol partially substitutes for N2O but also that, like NMDA channel blockers, ethanol pretreatment robustly and significantly facilitates the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O (Fig. 5).

The discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol have been repeatedly demonstrated to be based upon a combination of GABAA positive modulation, NMDA antagonism, and 5-HT1B/2C agonism (Grant et al., 1997), any one of which alone is sufficient to elicit ethanol-like stimulus effects. As we had already determined the degree of NMDA and GABAergic involvement in the stimulus effects of N2O, we examined both the 5-HT1B/2C agonist mCPP, which has ethanol-like effects in drug discrimination, as well as the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH DPAT. Neither mCPP nor 8-OH-DPAT produced N2O-like stimulus effects (Table 2). Overall, these findings suggest that the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of N2O are probably mediated exclusively through a common NMDA channel blocker–like cue component (Grant and Colombo, 1993; Shelton and Grant, 2002; Vivian et al., 2002).

In summary, our results probe the most probable receptor mechanisms underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of N2O. Of these mechanisms, the only class of drugs that engendered meaningful levels of N2O-appropriate responding were NMDA receptor channel blockers. However, even the channel blockers failed to elicit full substitution, suggesting that other mechanisms are also involved in transducing the stimulus effects of N2O. Several additional candidate mechanisms have been suggested by the literature, including 5-HT3 antagonism (Yamakura and Harris, 2000; Suzuki et al., 2002), neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine inhibition (Yamakura and Harris, 2000; Suzuki et al., 2003), interactions with neuronal nitric oxide synthase enzymes (for a review, see Emmanouil and Quock, 2007), or TREK-1 potassium channel activation (Gruss et al., 2004). Additional research examining these mechanisms will be required to fully characterize the discriminative stimulus properties of N2O.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Galina Slavova-Hernandez for technical assistance as well as Kate Nicholson and Matthew Banks for input on test drug selection.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- gaboxadol

4,5,6,7-tetrahydroisoxazolo[4,5-c]pyridine-3-ol

- CGS-19755

cis-4-[phosphomethyl]-piperidine-2-carboxylic acid

- FR

fixed ratio

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin

- L-701,324

7-chloro-4-hydroxy-3-(3-phenoxy)phenyl-2(1H)-quinolinone

- mCPP

1-(3-chlorophenyl)piperazine hydrochloride

- (+)-MK-801 maleate

(5S,10R)-(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- N2O

nitrous oxide

- 8-OH DPAT

(±)-8-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin hydrobromide

- SNC-80

(+)-4-[(αR)-α-((2S,5R)-4-allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide

- SR-95531

6-imino-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1(6H)-pyridazinebutanoic acid hydrobromide

- U50-488H

trans-(±)-3,4-dichloro-N-methyl-N-[2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)cyclohexyl]benzeneacetamide hydrochloride

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Richardson, Shelton.

Conducted experiments: Richardson.

Performed data analysis: Richardson, Shelton.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Richardson, Shelton.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants R01-DA020553 and T32-DA007027].

References

- Balon N, Dupenloup L, Blanc F, Weiss M, Rostain JC. (2003) Nitrous oxide reverses the increase in striatal dopamine release produced by N-methyl-aspartate infusion in the substantia nigra pars compacta in rats. Neurosci Lett 343:147–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley P, Ratti E, Balster R, Willetts J, Trist D. (2002) The selective glycine antagonist gavestinel lacks phencyclidine-like behavioral effects. Behav Pharmacol 13:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman NJ, Zacny JP, Walker DJ. (2006) Within-subject comparison of the subjective and psychomotor effects of a gaseous anesthetic and two volatile anesthetics in healthy volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend 81:89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss CI. (1967) Statistics in biology: statistical methods for research in the natural sciences, McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Wiley J, Jones H, Balster R. (1999) Phencyclidine-and diazepam-like discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants in mice. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 7:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert F. (1999) Drug discrimination in neurobiology. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech DA, Quock RM. (1993) Nitrous oxide induces an anxiolytic-like effect in the conditioned defensive burying paradigm, which can be reversed with a benzodiazepine receptor blocker. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 113:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech DA, Green DA. (1992) Anxiolytic effects of nitrous oxide in mice in the light-dark and holeboard exploratory tests. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 109:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzoljic M, Van Duijn B. (1998) Nitrous oxide-induced enhancement of gamma-aminobutyric acid-A-mediated chloride currents in acutely dissociated hippocampal neurons. Anesthesiology 88:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouil DE, Dickens AS, Heckert RW, Ohgami Y, Chung E, Han S, Quock RM. (2008) Nitrous oxide-antinociception is mediated by opioid receptors and nitric oxide in the periaqueductal gray region of the midbrain. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 18:194–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouil DE, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Hagihara PT, Quock DG, Quock RM. (2006) A study of the role of serotonin in the anxiolytic effect of nitrous oxide in rodents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 84:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. (2007) Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog 54:9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian C, Roullet P. (2004) Hippocampal CA3-region is crucial for acquisition and memory consolidation in Morris water maze task in mice. Behav Brain Res 154:365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Howard MO, Perron BE. (2009) Nitrous oxide inhalation among adolescents: prevalence, correlates, and co-occurrence with volatile solvent inhalation. J Psychoactive Drugs 41:337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Colombo G, Gatto GJ. (1997) Characterization of the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of 5-HT receptor agonists as a function of ethanol training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 133:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant K, Colombo G. (1993) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol: effect of training dose on the substitution of N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 264:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss M, Bushell TJ, Bright DP, Lieb WR, Mathie A, Franks NP. (2004) Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane. Mol Pharmacol 65:443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapfelmeier G, Zieglgänsberger W, Haseneder R, Schneck H, Kochs E. (2000) Nitrous oxide and xenon increase the efficacy of GABA at recombinant mammalian GABAA receptors. Anesth Analg 91:1542–1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes MD, Hymson DL. (1984) Nitrous oxide generalizes to a discriminative stimulus produced by ethylketocyclazocine but not morphine. Eur J Pharmacol 105:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevtović-Todovorić V, Todorović SM, Mennerick S, Powell S, Dikranian K, Benshoff N, Zorumski CF, Olney JW. (1998) Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotectant and neurotoxin. Nat Med 4:460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koek W, Kleven M, Colpaert F. (1995) Effects of the NMDA antagonist, dizocilpine, in various drug discriminations: characterization of intermediate levels of drug lever selection. Behav Pharmacol 6:590–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosobud AE, Kebabian CE, Rebec GV. (2006) Nitrous oxide acutely suppresses ethanol consumption in HAD and P rats. Int J Neurosci 116:835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T, Fukuda K. (2010) Involvement of the kappa-opioid receptor in nitrous oxide-induced analgesia in mice. J Anesth 24:297–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Quock RM. (2001) Comparison of N2O-and chlordiazepoxide-induced behaviors in the light/dark exploration test. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 68:789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D, von Haebler D, Winter C, Juckel G, Heinemann U. (2008) A single application of MK-801 causes symptoms of acute psychosis, deficits in spatial memory, and impairment of synaptic plasticity in rats. Hippocampus 18:125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennerick S, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Shen W, Olney JW, Zorumski CF. (1998) Effect of nitrous oxide on excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission in hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci 18:9716–9726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JL, Quock RM. (1992) Contrasting influences of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in nitrous oxide antinociception in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 41:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaida K, Shichino T, Fukuda K. (2007) Nitrous oxide increases serotonin release in the rat spinal cord. J Anesth 21:433–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagele P, Metz L, Crowder C. (2004) Nitrous oxide (N2O) requires the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor for its action in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:8791–8796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2011) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson K, Balster R. (2003) Evaluation of the Pencyclidine-like discriminative stimulus effects of novel NMDA channel blockers in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 170:215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson K, Balster R. (2009) The discriminative stimulus effects of N-methyl-d-aspartate glycine-site ligands in NMDA antagonist-trained rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 203:441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata J, Shiraishi M, Namba T, Smothers CT, Woodward JJ, Harris RA. (2006) Effects of anesthetics on mutant N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318:434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Kohno T, Sakimura K, Baba H. (2010) Reduced immobilizing properties of isoflurane and nitrous oxide in mutant mice lacking the N-Methyl-d-aspartate receptor GluR epsilon 1 subunit are caused by the secondary effects of gene knockout. Anesth Analg 110:461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleszak E, Wlaz P, Szewczyk B, Wlaz A, Kasperek R, Wróbel A, Nowak G. (2011) A complex interaction between glycine/NMDA receptors and serotonergic/noradrenergic antidepressants in the forced swim test in mice. J Neural Transm 118:1535–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quock R, Emmanouil D, Vaughn L, Pruhs R. (1992) Benzodiazepine receptor mediation of behavioral effects of nitrous oxide in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 107:310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K, Shelton K. (2014) Discriminative stimulus effects of nitrous oxide in mice: comparison with volatile hydrocarbons and vapor anesthetics. Behav Pharmacol 25:2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DJ, Zivkovic B. (1989) The discriminative stimulus effects of MK-801: generalization to other N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists. J Psychopharmacol 3:198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Kobayashi E, Murayama T, Mishina M, Seo N. (2005) Effect of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor epsilon 1 subunit gene disruption of the action of general anesthetic drugs in mice. Anesthesiology 102:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton K, Balster R. (2004) Effects of abused inhalants and GABA-positive modulators in dizocilpine discriminating inbred mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 79:219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton K, Grant K. (2002) Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:747–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Koyama H, Sugimoto M, Uchida I, Mashimo T. (2002) The diverse actions of volatile and gaseous anesthetics on human-cloned 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Anesthesiology 96:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Ueta K, Sugimoto M, Uchida I, Mashimo T. (2003) Nitrous oxide and xenon inhibit the human (alpha7) 5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expressed in Xenopus oocyte. Anesth Analg 96:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ, Murray RB. (1987). Manual of pharmacologic calculations with computer programs. 2nd ed. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian JA, Waters CA, Szeliga KT, Jordan K, Grant KA. (2002) Characterization of the discriminative stimulus effects of N-methyl-d-aspartate ligands under different ethanol training conditions in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 162:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DJ, Zacny JP. (2001) Lack of effects of ethanol pretreatment on the abuse liability of nitrous oxide in light and moderate drinkers. Addiction 96:1839–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessinger W, Li M, McMillan D. (2011) Drug discrimination in pigeons trained to discriminate among morphine, U50488, a combination of these drugs, and saline. Behav Pharmacol 22:468–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlaz P, Poleszak E. (2011) Differential effects of glycine on the anticonvulsant activity of D-cycloserine and L-701,324 in mice. Pharmacol Rep 63:1231–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakura T, Harris RA. (2000) Effects of gaseous anesthetics nitrous oxide and xenon on ligand-gated ion channels: comparison with isoflurane and ethanol. Anesthesiology 93:1095–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny J, Coalson D, Lichtor J, Yajnik S, Thapar P. (1994) Effects of naloxone on the subjective and psychomotor effects of nitrous oxide in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 49:573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny J, Conran A, Pardo H, Coalson D, Black M, Klock PA, Klafta JM. (1999) Effects of naloxone on nitrous oxide actions in healthy volunteers. Pain 83:411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Yajnik S, Coalson D, Lichtor JL, Apfelbaum JL, Rupani G, Young C, Thapar P, Klafta J. (1995) Flumazenil may attenuate some subjective effects of nitrous oxide in humans: a preliminary report. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 51:815–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny J, Walker D, Derus L. (2008) Choice of nitrous oxide and its subjective effects in light and moderate drinkers. Drug Alcohol Depend 98:163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]