Abstract

Astrocytes are the most abundant glial cells in the brain and are responsible for diverse functions, from modulating synapse function to regulating the blood-brain barrier. In vivo, these cells exhibit a star-shaped morphology with multiple radial processes that contact synapses and completely surround brain capillaries. In response to trauma or CNS disease, astrocytes become reactive, a state associated with profound changes in gene expression, including upregulation of intermediate filament proteins, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The inability to recapitulate the complex structure of astrocytes and maintain their quiescent state in vitro is a major roadblock to further developments in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Here, we characterize astrocyte morphology and activation in various hydrogels to assess the feasibility of developing a matrix that mimics key aspects of the native microenvironment. We show that astrocytes seeded in optimized matrix composed of collagen, hyaluronic acid, and matrigel exhibit a star-shaped morphology with radial processes and do not upregulate GFAP expression, hallmarks of quiescent astrocytes in the brain. In these optimized gels, collagen I provides structural support, HA mimics the brain extracellular matrix, and matrigel provides endothelial cell compatibility and was found to minimize GFAP upregulation. This defined 3D microenvironment for maintaining human astrocytes in vitro provides new opportunities for developing improved models of the blood-brain barrier and studying their response to stress signals.

Keywords: astrocytes, GFAP expression, activation, extracellular matrix, hydrogel

1. Introduction

Astrocytes, the most prevalent type of glial cell in the brain, have traditionally been considered supporting cells for neural function. However, it is now recognized that astrocytes participate in a range of brain functions, including regulating the formation and dissolution of synapses, maintaining and repairing the blood-brain barrier, and responding to tissue damage [1-4]. In response to trauma or pathological tissue damage astrocytes become activated, a process known as reactive gliosis [5-7]. While activated astrocytes help to repair damage in the brain, they have also been implicated in causing neural damage [4, 6], and accelerating tumor growth and invasiveness [8, 9]. Astrocyte activation is characterized by marked changes in protein expression [5, 7, 10], a hallmark of which is the increased expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [5, 11].

Astrocytes typically have star-shaped morphologies with small cell bodies, and radial branched processes, and occupy distinct domains [12]. Protoplasmic astrocytes in the human cortex, have a cell body approximately 10 μm in diameter and an overall diameter of about 150 μm [12]. Astrocyte processes have been estimated to contact tens of thousands of neural synapses per cell [13], while process end-feet also completely surround brain capillaries [12]. GFAP is widely used as a marker for astrocyte identification [14].

The brain microenvironment plays a crucial role in regulating astrocyte structure and function. The brain is composed mostly of neurons and glial cells, which account for 75 - 90% of the total brain volume [15, 16]. The extracellular space contains a complex extracellular matrix that is primarily composed of hyaluronic acid (HA), proteoglycans, and tenascins [17, 18]. In addition, laminin is present in small quantities in the developing brain and in the injured adult brain [19]. Many common extracellular matrix proteins, such as fibronectin and collagen, are not present in the brain [17].

There are two major challenges in culturing astrocytes for brain research: (1) achieving physiological cell morphology and (2) maintaining a quiescent or non-activated state with low levels of GFAP expression. Rat astrocytes in primary cultures containing collagen adopt a rounded morphology with short processes and express high levels of GFAP expression after 24 h in culture [20]. Similar rounded morphology and high levels of GFAP expression were reported for a human astrocyte cell line in gels with 1 mg mL−1 collagen and different concentrations of HA [21]. Mouse astrocytes cultured in scaffolds formed from 1.2 μm diameter electrospun polyurethane fibers coated with poly-L-ornithine or lysine showed long, branched processes but exhibited high levels of GFAP expression [11], demonstrating that the local microenvironment has a profound influence on astrocyte phenotype. These studies highlight the difficulty in recapitulating the characteristic morphology and non-activated state in cell culture. Here we recapitulate the morphology and very low levels of activation of quiescent human astrocytes.

We hypothesized that astrocytes cultured in a 3D matrix that provides structural support and appropriate extracellular matrix factors will recapitulate the characteristic star-shaped morphology and low levels of GFAP expression typical of quiescent astrocytes. To test this hypothesis, we cultured human fetal derived astrocytes in four classes of gels: HA gels, collagen gels, collagen/HA gels, and gels composed of collagen, HA, and matrigel. We show that astrocytes cultured in gels with collagen I for structural support (provided in vivo by the high density of cell processes and dendrites), HA to mimic the brain ECM, and matrigel for endothelial cell compatibility, exhibit a highly branched morphology and very low levels of activation. Recapitulating the physiological properties of astrocytes in this in vitro environment provides a new platform to explore the role of astrocytes in diverse functions, such as cell and tissue regeneration, blood-brain barrier regulation, and tumerogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell culture

Primary human fetal-derived astrocytes were obtained as described previously [22-24], following approval by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board. Intraoperative human central nervous system tissues, gestational weeks 19 - 21, which were following written informed consent for clinical procedures, were used for this research as they are considered pathological waste. Neural cells were cultured first in suspension as neurospheres in low adherent flasks using DMEM/F12 (Sigma) medium with 2% B27 supplement, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), 20ng mL−1 of EGF (Peprotech) and bFGF (Peprotech), 10 ng mL−1 of LIF (Millipore), and 5 μg mL−1 of heparin (Sigma). In order to obtain astrocytes, neurospheres were mechanically dissociated and single cells were plated on tissue culture flasks in DMEM/f12 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). To ensure that the cell population did not contain microglia, cells were stained for CD11b (AbCam). The lack of CD11b positive cells confirmed that there was no contamination by microglia.

2.2 3D astrocyte culture in hydrogels

Cells were seeded in various combinations of ECM protein hydrogels (Table 1) at a concentration of approximately 10,000 cells mL−1. Collagen gels were formed by neutralizing rat tail collagen I (BD) with NaOH, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 10X DMEM/F12 (Sigma) and astrocytes in cold, serum-free media were then added to the neutralized collagen. For the mixed gels, hyaluronic acid (HA, Glycosan HyStem Kit) was combined with poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) cross-linker (Glycosan Xtralink) at the manufacturer’s recommended ratio (8:1 ratio of HA: crosslinker). The cross-linked HA was then added to the neutralized collagen, followed by the growth factor reduced matrigel (BD), if applicable, followed by the 10X media and cells. All gels were formed in an ice water bath under sterile conditions, and gels were seeded into Nunc Lab Tek II 8-well chamber slides. Wells and pipet tips were kept in the freezer prior to mixing the gels, to ensure thorough mixing before gelation occurred.

Table 1.

Summary of hydrogel compositions studied. Concentrations are in mg mL−1.

| Category | Collagen | HA | Matrigel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Collagen/HA | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | |

|

Collagen/HA/Matrigel |

2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| 4 | 2 | 2 |

2.3 Physical characterization of the gels

The structure of the gels was characterized using scanning electron microscopy. Acellular gels were prepared as described above, with additional serum-free media to replace the volume of cells. Gels were incubated with deionized water overnight and then frozen with liquid nitrogen. The gels were then lyophilized overnight, mounted on stubs, and coated with platinum. Gels were imaged using a scanning electron microscope (FEI Quanta 200 Environmental SEM) under vacuum at 2.5 kV.

The mechanical properties of the gels were characterized using an atomic force microscope [25]. A Dimension 3100 AFM (Bruker Nano, Santa Barbara, CA) was used for the AFM measurements. The measured spring constant and length of the cantilever was 4.22 N m−1 and 225 μm, respectively (Budget Sensors; MagneticMulti75-G Cantilever). A 50 μm diameter soda lime glass microsphere (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) was attached to the end the cantilever using fast setting epoxy (Hardman, Royal Adhesives and Sealants, South Bend, IN). The AFM cantilever was lowered onto the hydrogel surface using the mechanical motor of the AFM, with an average rate of approach of 35.4 μm s−1. The mechanical motor was reversed once the sphere indented the gel, as noted by the sudden change in the photodiode signal. In relaxation experiments, the microsphere was driven into the hydrogel and allowed to relax at the maximum indentation (Supplemental Figure S1). All measurements were performed in PBS (Sigma).

2.4 Confocal microscopy

Cells in gels were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde after 24 hours of culture. After 10 minutes of fixing at room temperature, cells were washed 3x with PBS and then permeabilized with 0.01% Triton-X 100 for 3 minutes. Cells were then washed again 3x with PBS and blocked with 10% donkey serum (Millipore) in PBS for 30 minutes. Cells were then incubated with a 1:50 dilution of goat anti-GFAP (Santa Cruz) in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. After primary antibody incubation, cells were washed with PBS 3x for 1 hour per wash. Donkey-anti goat IgG 488 (Invitrogen, 1:100 dilution), CellMask 647 membrane stain (Invitrogen, 1:1000) and DAPI nuclear stain (1:2500 dilution) were added to blocking buffer incubated with the gels for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed 3x with PBS for 1 hour per wash. Confocal z-stacks were acquired with a Nikon TiE microscope equipped with an Andor camera using NIS elements software. Cells were selected randomly in phase contrast to ensure no selection for or against strongly GFAP-expressing cells occurred.

2.5 Analysis of cell morphology and GFAP expression

3D reconstructions of astrocyte filaments were generated from confocal Z-stacks using Imaris (Bitplane) to obtain quantitative morphological data. Filament tracing was done on the CellMask membrane stain channel to provide information about the morphology of the entire cell rather than only the GFAP-positive regions. Scholl analysis was performed to ascertain the amount of astrocyte processes intersecting concentric spheres around the cell body [26]. Total additive process length, degree of branching (# process ends / # primary processes), weighted process straightness (end-to-end distance over arc-length), and the overall cell diameter were calculated for each cell analyzed. The normalized GFAP expression was determined quantitatively from the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes) to the average intensity of the gel background. This method accounts for any drift in the microscope setup over the seven month duration of the experiments. The cell perimeter was defined from the membrane stain channel using ImageJ.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences in morphology and activation within each gel subcategory (collagen, collagen/HA, collagen/HA/matrigel) were determined using a Student’s t-test. Statistical significance is reported with respect to the best condition (lowest level of activation) in each sub-category. For the overall comparison between the best conditions in each subcategory, the best collagen-only control was used as the reference. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*), with P ≤ 0.01 represented with **, and P ≤ 0.001 represented with ***.

2.7 Compatibility with brain microvascular endothelial cells

To test the compatibility of the gels with endothelial cells, immortalized human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) [27] were grown to confluence on fibronectin-coated glass chamber slides. After confluence was achieved, 1.5 mm thick acellular gels were formed of top of the monolayers and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and blocked as described above, and incubated with rabbit anti-human ZO-1 (BD, 1:200 dilution) in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. After primary antibody incubation, cells were washed with PBS 3x for 1 hour per wash. Donkey-anti rabbit IgG 568 (Invitrogen, 1:100 dilution), and DAPI nuclear stain (1:2500 dilution) were added to blocking buffer incubated with the gels for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed 3x with PBS for 1 hour per wash. Cells were imaged with a Nikon TiE microscope equipped with a Photometrics camera. A schematic of this setup is shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

3. Results

3.1 Gel characterization

Four classes of gels were assessed for astrocyte culture in 3D: HA gels, collagen gels, collagen/HA gels, and gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel. Although HA is the main component of the brain ECM, astrocytes cultured in HA gels were balled up and did not exhibit characteristic astrocytic processes (Supplemental Figure S3) and were not studied further. This is not surprising since the ECM in the brain represents only 10 - 25 % of the total volume and HA is a relatively soft material [15, 16]. Although collagen I is not present in the brain, it is relatively inert matrix and provides structural support for cell culture. Matrigel was studied as a matrix component for compatibility with endothelial cells in blood-brain barrier (BBB) models.

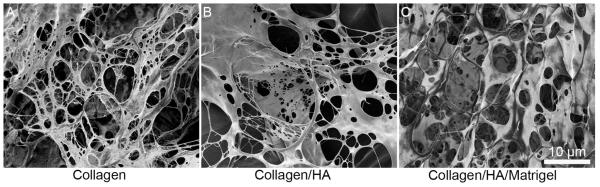

The structure of acellular gels was characterized using scanning electron microscopy. Collagen-only gels had a wide range of fiber sizes, with diameters from 100 to 1000 nm (Figure 1). Gels containing HA tended to have thicker fibers, in the range of 1 - 5 μm, with sheet-like regions characteristic of HA gels [21]. These larger fiber diameters may promote more physiological astrocyte morphology since most processes and dendrites in the brain have thicknesses within this fiber-size range.

Figure 1.

SEM images of acellular gels. (A) 6 mg mL−1 collagen. (B) 3 mg mL−1 collagen and 1 mg mL−1 HA. (C) 3 mg mL−1 collagen, 1.5 mg mL−1 HA, and 1.5 mg mL−1 matrigel. Collagen gels tended to have a very fibrous structure with smaller fibers, while the gels containing HA, had a hybrid fiber/sheet structure, with larger fibers.

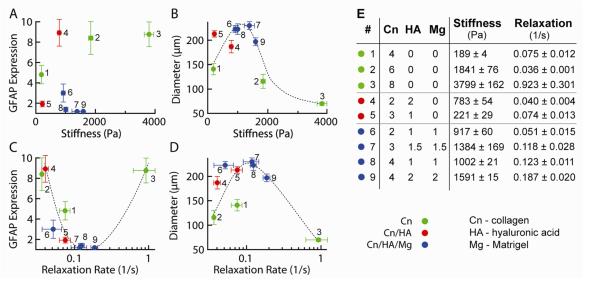

The mechanical properties of the acellular gels in buffer were characterized using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Force-distance measurements and relaxation curves were acquired for all gel compositions. The Hertz model was used to fit the indentation force curve to obtain Young’s modulus values, and relaxation curves were fit to an exponential decay curve to determine the relaxation rate. The stiffness of the gels varied from 150 to 4000 Pa and the relaxation rates from 0.03 to 0.9 s−1 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The modulus and relaxation time constant of the gel matrix influences astrocyte diameter and GFAP expression. (A) Normalized GFAP expression versus gel stiffness. (B) Astrocyte diameter versus gel stiffness. (C) Normalized GFAP expression versus gel relaxation rate. (D) Astrocyte diameter versus gel relaxation rate. (E) Gel compositions and relaxation and stiffness of each gel condition. Concentrations in mg mL−1, stiffness in Pa, relaxation in ×10−2 s−1.

3.2 Astrocyte characterization

Astrocytes were seeded in a variety of 3D matrices to determine the optimal composition for promoting physiological morphology and minimizing GFAP expression characteristic of inactive cells. The cell body and processes were delineated from the cell membrane stain. Cell morphology was determined from analysis of the number of processes as a function of distance around the cell body (Scholl analysis), the total additive process length, the degree of branching, the weighted process straightness, and the overall cell diameter.

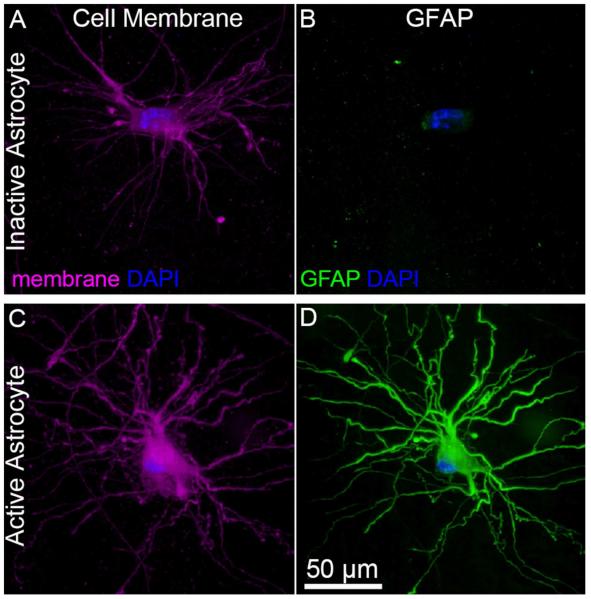

In general, fluorescence images of GFAP expression could be classified into two categories (Figure 2). For cells with low levels of GFAP expression in the cell body, the fluorescence intensity in the processes was nearly indistinguishable from the background. In contrast, cells with bright fluorescence throughout the cell body also tended to show enhanced fluorescence in the processes. Representative images of GFAP expression for all gels are shown in Supplemental Figure S4.

Figure 2.

Examples of inactive and active astrocytes in 3D cell culture. Human fetal derived astrocytes were seeded in a gel composed of 2 mg mL−1 collagen, 1 mg mL−1 HA, 1 mg mL−1 matrigel. Immunofluorescence images of DAPI (blue) and membrane (purple) or DAPI (blue) and GFAP (green). While both cells express the characteristic branched processes of physiological astrocytes, one cell expresses GFAP only in small quantities in the cell body, whereas the other cell shows very high expression levels of GFAP throughout the entire cell body and processes, characteristic of activation. The cell morphology and level of GFAP expression were quantitatively assessed for astrocytes in collagen gels, collagen/HA gels, and gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel (Figures 3 - 5). Comparison of the best gels from these three classes, including statistical analysis, is presented in Figure 6. We then analyze the relationship between the mechanical properties of the gels and the cell morphology and GFAP expression (Figure 7).

GFAP expression was determined quantitatively from the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes determined from the cell membrane stain) to the average intensity of the gel background. In general, for a normalized GFAP expression level less than 2, the cells showed low levels of expression in the cell body and negligible expression in the processes, whereas for a normalized GFAP expression level more than 4, most of the cells showed bright fluorescence in both the cell body and processes (Figure 2). Since GFAP overexpression is associated with astrocyte activation, we refer to cells with low levels of GFAP expression (ratio < 2) as inactive, and cells with high levels of GFAP expression (ratio > 8) as active.

Below we present quantitative analysis of cell morphology and GFAP expression of human astrocytes in the four classes of gels.

3.3 Astrocytes in HA gels

While the majority of the brain’s ECM is composed of hyaluronic acid (HA), culturing astrocytes in HA alone results in rounded, non-proliferative cells that do not extend processes (Supplemental Figure S3). Therefore, no further experiments were performed with HA gels.

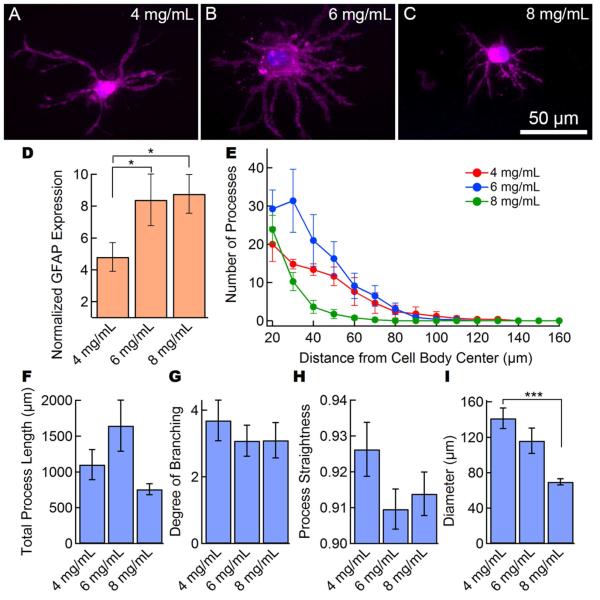

3.4 Astrocytes in collagen gels

Astrocytes in collagen gels, unlike cells in HA gels, expressed characteristic astrocyte processes (Figure 3), but almost all cells expressed high levels of GFAP in both the cell body and processes. In 4 mg mL−1 gels, the average normalized GFAP expression was 4.8, whereas in 6 mg mL−1 and 8 mg mL−1 gels, the normalized GFAP expression was 8.4 and 8.8, respectively (Figure 3D). A Scholl plot of the number of processes as a function of distance from the cell body (Figure 3E) shows that the average number of primary processes ranged from 20 to 30, although the extent of the processes was smallest for the 8 mg mL−1 gel. The total process length was 700 - 1600 μm, with the maximum process length at a gel concentration of 6 mg mL−1 (Figure 3F). The degree of branching, defined as the number of process ends divided by the number of primary processes, was 3 - 4 for all gels (Figure 3G), and the process straightness was 0.91 - 0.93 (Figure 3H) for all gel concentrations. The overall cell diameter decreased from about 140 μm for 4 mg mL−1 gels, to about 70 μm in the stiffer 8 mg mL−1 gels (Figure 3I). Overall, the 4 mg mL−1 and 6 mg mL−1 collagen gels resulted in astrocytes with longer processes and an overall diameter similar to astrocytes in the human brain [12].

Figure 3.

Astrocytes in collagen gels exhibit a star-shaped morphology but high levels of GFAP expression. Representative images of astrocytes in collagen gels: (A) 4 mg mL−1, (B) 6 mg mL−1, and (C) 8 mg mL−1 collagen type I. Images are maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks. Cells stained for CellMask membrane stain (purple) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). GFAP expression and morphological analysis of astrocytes in collagen gels (N = 8 - 12 cells per condition). (D) Activation analysis of the cells shows a high degree of activation at all collagen concentrations. The normalized GFAP expression is the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes) to the average intensity of the gel background. (E) Scholl analysis shows the overall morphological characteristics. (F) Total process length, (G) degree of branching, (H) process straightness, and (I) overall cell diameter for astrocytes in collagen gels. Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using a student’s t-test test compared to the 4 mg mL−1 collagen gel. *** P ≤ 0.001, ** P ≤ 0.01. * P≤ 0.05.

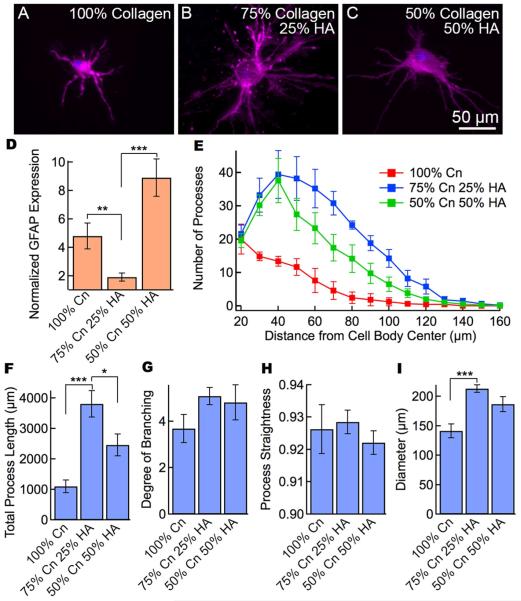

3.5 Collagen and HA gels

While astrocytes in the collagen-only gels exhibited numerous astrocyte-like processes, the high levels of GFAP expression indicate astrocyte activation. To assess the influence of HA on GFAP expression and cell morphology, we seeded astrocytes in collagen/HA gels (Figure 4A-C). All gels had a total monomer concentration of 4 mg mL−1. Gels with 25% HA exhibited a normalized GFAP expression of 1.9, significantly lower than any of the collagen gels (Figure 3), whereas cells cultured in gels with 50% collagen and 50% HA and showed higher GFAP expression than the corresponding pure collagen gel. The average number of primary processes was about 20 for all three conditions, however, with the addition of HA to the matrix the number of processes increased to about 40 at a distance of 40 - 50 μm from the cell body (Figure 4E). The addition of 25 - 50% HA to the matrix results in a significant increase in total process length (Figure 4F), although only small changes in the degree of branching (Figure 4G), and process straightness (Figure 4H). The overall astrocyte size increased from about 140 μm in collagen gels, to 180 - 210 μm with the addition of HA to the matrix (Figure 4I).

Figure 4.

The addition of HA to collagen gels modulates cell morphology and GFAP expression. Immunofluorescence images of astrocytes in collagen/HA gels with varying amounts of HA. (A) 100 % collagen HA (4 mg mL−1 collagen), (B) 75 % collagen and 25 % HA (3 mg mL−1 collagen + 1 mg mL−1 HA) and (C) 50 % collagen and 50 % HA (2 mg mL−1 collagen + 2 mg mL−1 HA). In all cases the total concentration of the gels was 4 mg mL−1. Images are maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks. Cells stained for CellMask membrane stain (purple) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Differences in overall cell diameter can be easily seen in these representative images upon the incorporation of HA in the hydrogels. GFAP expression and morphological analysis of astrocytes in gels containing collagen I and HA with a total monomer concentration of 4 mg mL−1 (N = 10 - 18 cells per condition). (D) Normalized GFAP expression shows that the incorporation of 25% HA results in very low GFAP expression. The normalized GFAP expression is the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes) to the average intensity of the gel background. (E) Scholl analysis of astrocytes showing overall morphological characteristics. (F) Total process length, (G) degree of branching, (H) process straightness, and (I) overall cell diameter for astrocytes in collagen gels. Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using a student’s t-test test compared to the 3 mg mL−1 collagen, 1 mg mL−1 HA gel. *** P ≤ 0.001, ** P ≤ 0.01. * P≤ 0.05.

3.6 Astrocytes in gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel

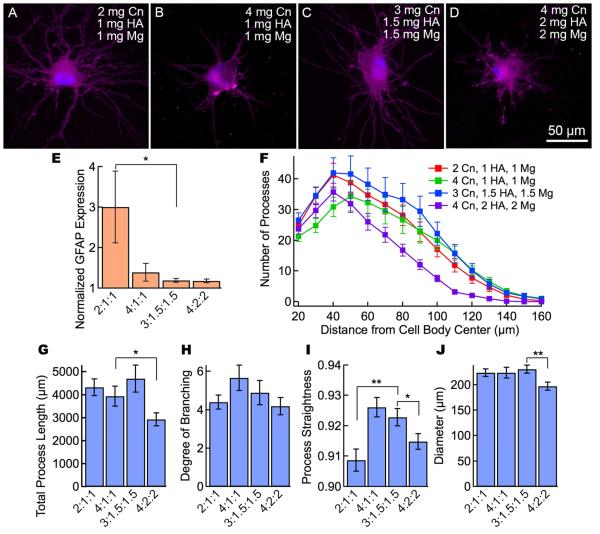

While gels containing 75% collagen and 25% HA resulted in low GFAP expression and enhanced morphology as compared to collagen only gels, the addition of matrigel to the matrix was necessary to ensure endothelial monolayer survival (Supplemental Figure S5). Astrocytes in gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel, similar to cells in collagen/HA gels, showed the characteristic star-shaped morphology with multiple radial processes (Figure 5A-D).

Figure 5.

Gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel at concentrations greater than 4 mg mL−1 show astrocytic morphology and very low levels of GFAP expression. Representative fluorescence images of astrocytes in gels containing collagen (Cn), HA, and matrigel (Mg). The ratio X:Y:Z corresponds to the monomer concentration in mg mL−1 (X - collagen, Y - HA, Z - matrigel). (A) 2 mg mL−1 collagen, 1 mg mL−1 HA, and 1 mg mL−1 matrigel (2:1:1). (B) 4 mg mL−1 collagen, 1 mg mL−1 HA, and 1 mg mL−1 matrigel (4:1:1). (C) 3 mg mL−1 collagen, 1.5 mg mL−1 HA, and 1.5 mg mL−1 matrigel (3:1.5:1.5). (D) 4 mg mL−1 collagen, 2 mg mL−1 HA, and 2 mg mL−1 matrigel (4:2:2). Images are maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks. Cells stained for CellMask membrane stain (purple) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). GFAP expression and morphological analysis of astrocytes in gels containing collagen I, HA, and matrigel (N = 22 - 28 cells per condition. (E) Activation analysis of the cells shows that the incorporation of HA and matrigel results in fewer cells expressing GFAP. The normalized GFAP expression is the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes) to the average intensity of the gel background. (F) Scholl analysis of the astrocytes shows overall morphological characteristics. (G) Total process length, (H) degree of branching, (I) process straightness, and (J) overall cell diameter for astrocytes in collagen gels. Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using a student’s t-test test compared to the 3 mg mL−1 collagen, 1.5 mg mL−1 HA, 1.5 mg mL−1 Matrigel gel. *** P ≤ 0.001, ** P ≤ 0.01. * P≤ 0.05.

The addition of matrigel to the matrix strongly influenced GFAP expression (Figure 5E). The 2:1:1 (Cn:HA:Mg) gel exhibited a normalized GFAP expression of 3.0, whereas the 4:1:1, 3:1.5:1.5 and 4:2:2 gels exhibited expression levels of 1.4, 1.2, and 1.2, respectively. The Scholl plots (Figure 5F) were similar to those for collagen/HA gels (Figure 4E), with about 20 primary processes increasing to a maximum of 35 - 40 process at a distance of 40 - 50 μm from the center of the cell body. The total process length (Figure 5G), the degree of branching (Figure 5H), and the overall diameter (Figure 5J) were relatively independent of matrigel concentration.

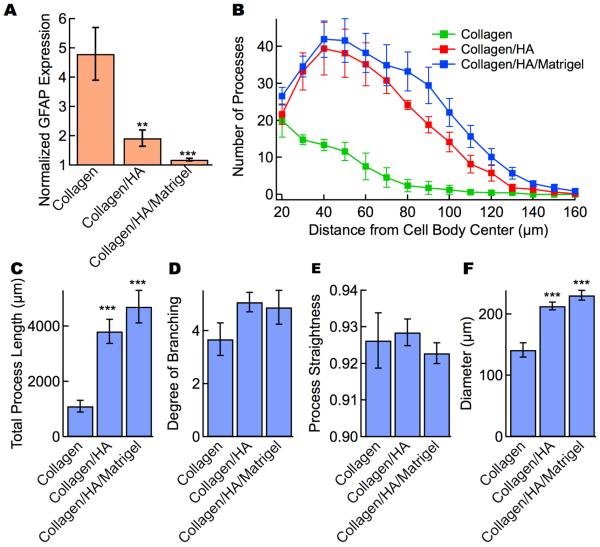

3.7 Comparison of astrocytes in collagen, collagen/HA, and collagen/HA/matrigel

To highlight the influence of matrix composition on astrocyte morphology and GFAP expression, we compare the best results for each of the three classes of gel (Figure 6): (1) 4 mg mL−1 collagen, (2) 3 mg mL−1 collagen + 1 mg mL−1 HA, and (3) 3 mg mL−1 collagen, 1.5 mg mL−1 HA, and 1.5 mg mL−1 matrigel. The latter two conditions had indistinguishable cell morphologies compared to the best collagen-only gel with diameters larger than 200 μm, total process lengths > 3800 μm, and a degree of branching > 4. The normalized GFAP expression for the best collagen/HA and collagen/HA/matrigel gels were 1.9 and 1.2, respectively, significantly lower than for the best collagen gel (4.8).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the best conditions of collagen gels, collagen/HA gels, and collagen/HA/matrigel gels. Collagen: 4 mg mL−1 collagen, collagen/HA: 3 mg mL−1 collagen + 1 mg mL−1 HA, and collagen/HA/matrigel: 4 mg mL−1 collagen, 2 mg mL−1 HA, and 2mg mL−1 matrigel. (A) Normalized GFAP expression. The normalized GFAP expression is the ratio of the average fluorescence per pixel in the cell (cell body and processes) to the average intensity of the gel background. (B) Scholl analysis of the astrocyte processes. Morphological parameters for astrocytes in gels: (C) total process length, (D) degree of branching, (E) process straightness, and (F) overall cell diameter. Data represent mean ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using a student’s t-test test compared to the 4 mg mL−1 collagen gel. *** P ≤ 0.001, ** P ≤ 0.01.

3.8 GFAP expression, cell morphology, and gel stiffness

The stiffness and relaxation rate of the gels also plays a role in modulating cell morphology (Figure 7). The elastic modulus and shear modulus of collagen gels increases with increasing monomer concentration, but is also dependent on the gel microstructure which, in turn, is dependent on experimental conditions such as gelation temperature and pH [28, 29]. For collagen gels with concentration from 3 mg mL−1 to 9 mg mL−1 the elastic modulus has been reported to increase from about 500 Pa to about 12 kPa and the shear modulus from about 200 Pa to about 5 kPa (an E/G′ ratio of 2.25) [29]. Using AFM indentation, we obtain elastic modulus values of 190 Pa for 2 mg mL−1 collagen and 3800 for 8 mg mL−1 collagen, in the range reported in the literature.

No clear correlation was observed between the measured gel stiffness and GFAP expression, although the lowest levels of GFAP expression were generally found for gel stiffnesses of 1000 - 1500 Pa (Figure 7A). The overall cell diameter shows a maximum of about 220 μm corresponding to gels with stiffness in the range from 900 - 1500 Pa (Figure 7A). The maximum in cell diameter occurs at a stiffness that is somewhat larger than the bulk shear modulus of 200 - 300 Pa reported for human, rat, and pig brain [30, 31], however, our gels have a very low density of cells compared to brain tissue. GFAP expression had a very strong correlation with the gel relaxation rate (Figure 7C), which is related to the stress relaxation modulus. The minimum in GFAP expression was observed at a relaxation rate of 0.1 - 0.2 s−1. The overall cell diameter also showed a maximum as a function of the gel relaxation rate (Figure 7D).

These results indicate that the mechanical properties of gels play an important role in modulating the morphology of astrocytes and their expression of GFAP. In soft gels, the matrix is easily deformed, however, the low stiffness and relaxation rate reduces the traction forces necessary for extending new processes. In stiff gels, there is sufficient traction for new processes but it is difficult to deform the matrix. Therefore, it appears there is an optimum range of stiffness and relaxation rate required for astrocytes to adopt a physiological morphology.

3.9 Compatibility with endothelial cells

To test the compatibility of these gels with brain microvascular endothelial cells, gels were formed on top of confluent monolayers of HBMECs. After 24 hours, HBMECs under collagen and collagen/HA gels showed low expression levels of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (Supplemental Figure S5). In contrast, HBMEC monolayers under gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel showed ZO-1 expression and localization at the cell-cell junctions typical of monolayers in 2D culture (Supplementary Figure S5) [22]. The presence of endothelial cell tight junctions is essential for the creation of physiologically relevant BBB models, indicating that these in vitro conditions are suitable for establishing key features of endothelial cells and astrocytes in brain.

4. Discussion

Astrocytes extend highly ramified processes that make contact with blood vessels, synapses, nodes of Ranvier, and other neuronal and non-neural elements, placing them in a unique position to control brain metabolism by providing an interface between the circulation and the brain parenchyma. How they perform this homeostatic function is not well understood. Much of our knowledge about the functions of these cells comes from studies in mice and rats. Although human astrocytes are larger and more diverse in their structure [12], much less is known about their physiological characteristics. Given the limitations associated with analysis of cellular properties in the intact human CNS, in vitro studies provide crucial insight to the characteristics of these cells, necessitating development of conditions that retain their in vivo properties. Here we examined how various culture conditions influence the morphological maturation of astrocytes and their reactive state and define a 3D matrix that enables vigorous process formation by astrocytes but retains their quiescent state.

GFAP is a widely used biomarker of reactive gliosis, providing a ready measure of the transformation of astrocytes in different pathological conditions. In our studies, the average normalized GFAP expression ranged from < 2 (1.4, 1.2, 1.2, and 1.9) for three Cn/HA/Mg gels and one Cn/HA gel, to 8 - 10 for two collagen gels and one Cn/HA (8.4, 8.4, and 8.7). Cells in the 4 mg mL−1 collagen gel, and the 2:1:1 (Cn:HA:Mg) gel, showed intermediate values of GFAP expression (4.8 and 3.0, respectively). For GFAP ratios < 2, fluorescence images of cells generally showed weak expression in the cell body and negligible expression in the processes. In contrast, cells with GFAP ratios > 8 showed high intensity in both cell body and processes. The maximum increase in GFAP expression between conditions is approximately 8-fold. A 7.5-fold increase in the gene encoding for GFAP has been reported for cortical astrocytes in a mouse model following activation induced by transient ischemia [10]. Taken together, these results suggest that astrocytes in 3D gels with low GFAP ratios are quiescent, whereas cells with high GFAP ratios are activated.

Although collagen gels are commonly used as a matrix for 3D cell culture [32, 33], astrocytes in collagen gels are smaller, less branched, and exhibit high levels of GFAP expression in the cell body and processes, characteristic of activated cells (Figure 3). Mixed collagen/HA gels were investigated as a matrix for astrocytes since HA is the major component of brain ECM. In addition, astrocytes express CD44, a receptor for HA, and hence the addition of HA to the matrix is expected to result in more physiological morphology [34]. The addition of HA results in an increase in the total process length, degree of branching, and overall cell diameter (Figure 4). The average normalized GFAP expression in gels with 75% collagen and 25% HA (4 mg mL−1 collagen + 1 mg mL−1 HA) was 1.9, significantly lower than in the corresponding 4 mg mL−1 collagen gel, where the normalized GFAP expression was 4.8. In gels with 50% collagen and 50% HA the normalized GFAP expression was 8.9 ± 1.3, similar to the higher collagen concentrations (Figure 4). Since cells in pure HA-crosslinker gels are rounded and do not exhibit radial processes, the increase in GFAP expression in 50% collagen - 50% HA gels can be ascribed to the increased HA concentration. The PEG-based crosslinker used in the HA-based gels is unlikely to have a significant influence on astrocyte activation, since PEG-based hydrogels implanted into primate brains have a minimal effect on GFAP expression in astrocytes [35].

Gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel exhibit similar morphological characteristics, typical of astrocytes in the human brain, and very low levels of GFAP expression (Figure 5). The 4:1:1, 3:1.5:1.5 and 4:2:2 gels exhibited expression levels of 1.4, 1.2, and 1.2, respectively, suggesting a quiescent or unactivated state. While laminin is known to promote neurite outgrowth [19, 36], and to exist in small quantities in the developing and injured brain [19], it is very rarely added to 3D matrices for brain cell culture. Matrigel, which is primarily composed of laminin, has been shown to promote endothelial cell growth and tubulogenesis in vitro [37].

Astrocytes imaged in collagen/HA and collagen/HA/matrigel gels were somewhat larger (≥ 200 μm diameter) compared to human protoplasmic astrocytes in vivo, which are approximately 150 μm in diameter [12, 14]. Detailed comparison of the size and morphology of astrocytes in the human brain is complicated by the fact that images are obtained from tissue sections from patients with epilepsy or brain cancer and use GFAP staining rather than a membrane stain [12]. In addition, human astrocytes in the brain tend to extend longer processes during development, which then retract into independent astrocyte domains as the cells are constrained by their neighbors [38]. In the experiments reported here, the astrocytes were seeded at a much lower density than in the brain for single-cell imaging, and hence were not confined by interactions with their neighbors. The degree of branching observed in these experiments was very similar to the degree of branching observed in astrocytes in the mouse optic nerve [39].

Comparison of cell morphology and GFAP expression (Supplemental Figure S6) suggests a correlation between cell morphology and activation. In general, cells with low GFAP expression had total processes length > 3000 μm, a degree of branching > 4, and a cell diameter > 180 μm.

Astrocytes in gels with collagen, HA, and matrigel were found to have nearly indistinguishable morphologies, likely due to the fact that all four conditions assayed had very similar stiffnesses (Figure 7). However, GFAP expression was significantly upregulated in 2:1:1 (Cn:HA:Mg) gels. Since this gel matrix had a much lower relaxation rate (which corresponds to slower stress relaxation) compared to all of the other conditions in this category (Figure 7), it is possible that the mechanical properties of this gel were responsible for the increased activation response. This effect likely also explains the dramatic difference in activation between the two gels containing both collagen and HA. The very low relaxation rate measured in the 2 mg/mL collagen, 2 mg/mL HA gel likely explains the increased GFAP expression of astrocytes in this gel. From these experiments, it seems that sufficiently low (<0.1 s−1) or high (>0.2 s−1) gel relaxation rates results in increased GFAP expression.

Astrocytes are known to be an essential component of the blood-brain barrier, participating in BBB repair and maintenance, producing proteins, such as GDNF and bFGF, that enhance BBB tightness, and regulating water, ion, and amino acid homeostasis [2, 40]. While many in vitro models of the human BBB incorporate astrocytes, most of these models involve the culture of astrocytes in 2D, and often do not include contact with endothelial cells [41-43]. These astrocytes tend to be spindle-shaped and almost always express markers associated with astrocyte activation [20]. Through this exploration of hydrogel compositions, we developed a new in vitro platform for the study of the blood-brain barrier may promote a deeper understanding of how astrocytes influence the formation and function of the BBB, and reveal new approaches for limiting damage from stroke, slowing tumor formation, and enhancing the entry of therapeutic molecules to the CNS.

5. Conclusions

The morphology and level of GFAP expression in human astrocytes is strongly dependent on the composition and mechanical properties of the 3D microenvironment. To test the hypothesis that astrocytes cultured in a 3D matrix that provides structural support and appropriate extracellular matrix factors will recapitulate the characteristic star-shaped morphology and low levels of GFAP expression typical of quiescent astrocytes, we cultured human astrocytes in four classes of gels: HA gels, collagen gels, collagen/HA gels, and gels composed of collagen, HA, and matrigel. Astrocytes cultured in gels composed of collagen, HA, and matrigel exhibited a highly branched morphology, typical of their morphology in vivo, and very low levels of GFAP expression, a hallmark of quiescent cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from NIH (AQH: R01NS070024; PCS: R01CA170629)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix. Supplementary Material

The supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the on-line version at doi:

References

- [1].Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: The revolution continues. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:626–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Figley CR, Stroman PW. The role(s) of astrocytes and astrocyte activity in neurometabolism, neurovascular coupling, and the production of functional neuroimaging signals. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;33:577–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oberheim NA, Wang XH, Goldman S, Nedergaard M. Astrocytic complexity distinguishes the human brain. Trends in Neurosciences. 2006;29:547–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ridet J, Privat A, Malhotra S, Gage F. Reactive astrocytes: cellular and molecular cues to biological function. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:570–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pekny M, Nilsson M. Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis. Glia. 2005;50:427–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends in Neurosciences. 2009;32:638–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fitzgerald DP, Palmieri D, Hua E, Hargrave E, Herring JM, Qian Y, et al. Reactive glia are recruited by highly proliferative brain metastases of breast cancer and promote tumor cell colonization. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2008;25:799–810. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Le DM, Besson A, Fogg DK, Choi K-S, Waisman DM, Goodyer CG, et al. Exploitation of astrocytes by glioma cells to facilitate invasiveness: a mechanism involving matrix metalloproteinase-2 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator–plasmin cascade. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:4034–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04034.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zamanian JL, Xu LJ, Foo LC, Nouri N, Zhou L, Giffard RG, et al. Genomic Analysis of Reactive Astrogliosis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:6391–410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6221-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Puschmann TB, Zanden C, De Pablo Y, Kirchhoff F, Pekna M, Liu J, et al. Bioactive 3D cell culture system minimizes cellular stress and maintains the in vivo-like morphological complexity of astroglial cells. Glia. 2013;61:432–40. doi: 10.1002/glia.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Oberheim NA, Takano T, Han X, He W, Lin JHC, Wang F, et al. Uniquely Hominid Features of Adult Human Astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:3276–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4707-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–31. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Oberheim NA, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Heterogeneity of astrocytic form and function. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;814:23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kinney JP, Spacek J, Bartol TM, Bajaj CL, Harris KM, Sejnowski TJ. Extracellular sheets and tunnels modulate glutamate diffusion in hippocampal neuropil. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2013;521:448–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.23181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Syková E, Nicholson C. Diffusion in brain extracellular space. Physiological reviews. 2008;88:1277–340. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yamaguchi Y. Lecticans: organizers of the brain extracellular matrix. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences CMLS. 2000;57:276–89. doi: 10.1007/PL00000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zimmermann DR, Dours-Zimmermann MT. Extracellular matrix of the central nervous system: from neglect to challenge. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2008;130:635–53. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liesi P. Laminin-immunoreactive glia distinguish regenerative adult CNS systems from non-regenerative ones. The EMBO journal. 1985;4:2505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].East E, Golding JP, Phillips JB. A versatile 3D culture model facilitates monitoring of astrocytes undergoing reactive gliosis. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2009;3:634–46. doi: 10.1002/term.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rao SS, DeJesus J, Short AR, Otero JJ, Sarkar A, Winter JO. Glioblastoma Behaviors in Three-Dimensional Collagen-Hyaluronan Composite Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:9276–84. doi: 10.1021/am402097j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Levy AF, Zayats M, Guerrero-Cazares H, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Searson PC. Influence of Basement Membrane Proteins and Endothelial Cell-Derived Factors on the Morphology of Human Fetal-Derived Astrocytes in 2D. PloS one. 2014;9:e92165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Guerrero-Cazares H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Soriano-Navarro M, Zamora-Berridi G, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Cytoarchitecture of the lateral ganglionic eminence and rostral extension of the lateral ventricle in the human fetal brain. J Comp Neurol. 2011;519:1165–80. doi: 10.1002/cne.22566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ravin R, Blank PS, Steinkamp A, Rappaport SM, Ravin N, Bezrukov L, et al. Shear forces during blast, not abrupt changes in pressure alone, generate calcium activity in human brain cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Young JL, Engler AJ. Hydrogels with time-dependent material properties enhance cardiomyocyte differentiation in vitro. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1002–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lye-Barthel M, Sun D, Jakobs TC. Morphology of Astrocytes in a Glaucomatous Optic Nerve. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2013;54:909–17. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Nizet V, Kim KS, Stins M, Jonas M, Chi EY, Nguyen D, et al. Invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells by group B streptococci. Infection and Immunity. 1997;65:5074–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5074-5081.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Raub CB, Unruh J, Suresh V, Krasieva T, Lindmo T, Gratton E, et al. Image correlation spectroscopy of multiphoton images correlates with collagen mechanical properties. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94:2361–73. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Raub CB, Putnam AJ, Tromberg BJ, George SC. Predicting bulk mechanical properties of cellularized collagen gels using multiphoton microscopy. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6:4657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Georges PC, Miller WJ, Meaney DF, Sawyer ES, Janmey PA. Matrices with compliance comparable to that of brain tissue select neuronal over glial growth in mixed cortical cultures. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90:3012–8. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Prange MT, Margulies SS. Regional, directional, and age-dependent properties of the brain undergoing large deformation. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering-Transactions of the Asme. 2002;124:244–52. doi: 10.1115/1.1449907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7:211–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Girgrah N, Letarte M, Becker LE, Cruz TF, Theriault E, Moscarello MA. Localization of the CD44 glycoprotein to fibrous astrocytes in normal white matter and to reactive astrocytes in active lesions in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 1991;50:779–92. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bjugstad K, Redmond D, Jr, Lampe K, Kern D, Sladek J, Jr, Mahoney M. Biocompatibility of PEG-based hydrogels in primate brain. Cell transplantation. 2008;17:409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Deister C, Aljabari S, Schmidt CE. Effects of collagen 1, fibronectin, laminin and hyaluronic acid concentration in multi-component gels on neurite extension. Journal of Biomaterials Science-Polymer Edition. 2007;18:983–97. doi: 10.1163/156856207781494377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ito KI, Ryuto M, Ushiro S, Ono M, Sugenoya A, Kuraoka A, et al. Expression of tissue-type plasminogen-activator and its inhibitor couples with development of capillary network by human microvascular endothelial-cells on matrigel. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1995;162:213–24. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041620207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Freeman MR. Specification and Morphogenesis of Astrocytes. Science. 2010;330:774–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1190928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Butt AM, Colquhoun K, Tutton M, Berry M. 3-dimensional morphology of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the intact mouse optic-nerve. Journal of Neurocytology. 1994;23:469–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01184071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Abbott NJ. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions and blood-brain barrier permeability. Journal of Anatomy. 2002;200:629–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Thanabalasundaram G, Schneidewind J, Pieper C, Galla HJ. The impact of pericytes on the blood-brain barrier integrity depends critically on the pericyte differentiation stage. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2011;43:1284–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hatherell K, Couraud PO, Romero IA, Weksler B, Pilkington GJ. Development of a three-dimensional, all-human in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier using mono-, co-, and tri-cultivation Transwell models. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2011;199:223–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Nakagawa S, Deli MA, Kawaguchi H, Shimizudani T, Shimono T, Kittel A, et al. A new blood-brain barrier model using primary rat brain endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Neurochemistry International. 2009;54:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.