Abstract

Background:

Cognitive decline and dementia are an important problem affecting quality-of-life in elderly and their caregivers. There is regional variation in prevalence of cognitive decline as well as risk factors from region to region.

Aim:

The aim was to determine the prevalence of dementia and cognitive decline and its various risk factors in the elderly population of more than 60 years in Eastern Uttar Pradesh (India).

Materials and Methods:

A camp-based study was conducted on rural population of Chiraigaon block of Varanasi district from February 2007 to May 2007. Block has 80 villages, of which 11 villages were randomly selected. Eleven camps were organized for elderly people in 11 randomly selected villages on predetermined dates. A total of 728 elderly persons of age >60 years were examined, interviewed and data thus collected was analyzed. Elderly who got Hindi-mini-mental state examination (HMSE) score developed by Ganguli based on the Indo-US Cross-National Dementia Epidemiology Study) score ≤23 were evaluated further and in those with confirmed cognitive and functional impairment, diagnosis of dementia was assigned according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorder fourth edition criteria after ruling out any psychiatric illness or delirium. Based on International Classification of Diseases-10 diagnostic criteria sub-categorization of dementia was done.

Results:

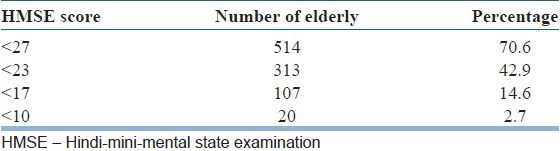

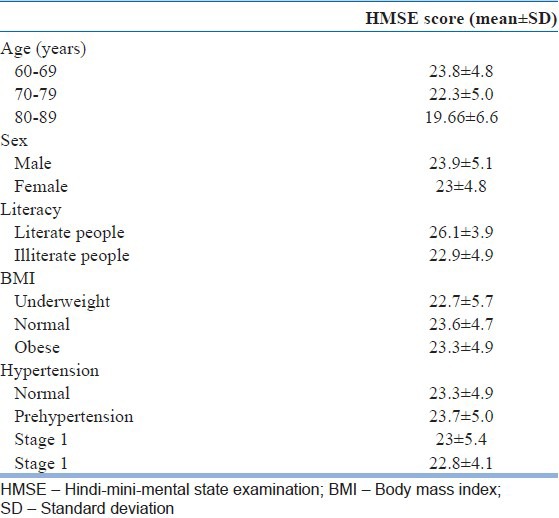

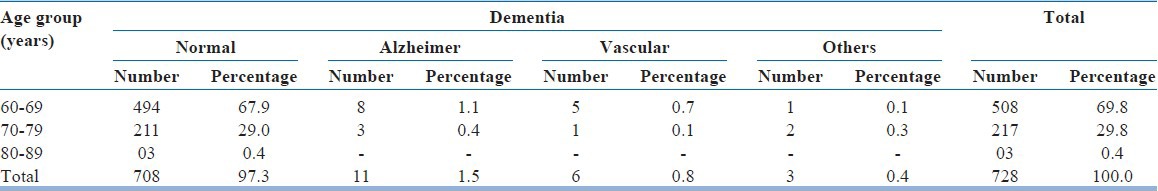

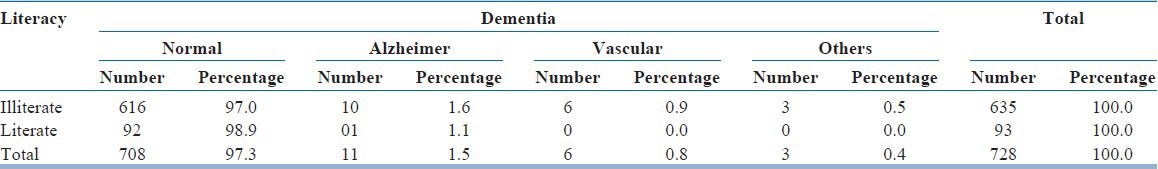

Mean, median and 10th percentile of HMSE of the study population were 23.4, 24 and 17, respectively. About 14.6% elderly had scored <17. 42.9% of rural elderly population had HMSE score <23, 70.6% <27 and 27.7% between 23 and 27. Literate people had statistically significant higher mean HMSE score (26.1 ± 3.9) than illiterate people (22.9 ± 4.9). Other risk factors were female gender, malnutrition, and obesity. Prevalence of dementia was 2.74%; in male 2.70% and in female 2.80%. Most common type of dementia was Alzheimer (male 1.5%, female 1.5%) followed by vascular (male 1.2%, female 0.6%) and others 0.6% (male 0%, female 0.6%).

Conclusions:

Study showed that a very high percentage of rural elderly attending health camps had poor cognitive function score; though the prevalence of dementia was relatively low. Alzheimer dementia was most common, followed by vascular dementia, which was predominant in males. Illiteracy, age, and under-nutrition were the most important risk factors for poor cognitive function. Our study suggest that cut-off of HMSE score should be 17 (10th percentile) for illiterate population.

Keywords: Dementia, elderly, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is an emerging health problem, as the elderly population is increasing so is the prevalence of dementia.[1,2,3,4,5,6] Cognitive impairment prevalence also increases with increasing age.[7,8,9] As such, there is scarcity of prevalence studies from Northern India due to ethnic and sociocultural diversities. There is regional variation in prevalence of cognitive decline as well as risk factors from region to region.[10] Epidemiological studies of dementia in person ≥60 years in urban and rural population of southern India had obtained prevalence rates of 27-33.6/1000 and 34-36/1000, respectively.[11,12,13] In a population aged ≥65 years from reported prevalence rate of dementia is 13.6/1000 and 18/1000 from a rural community of Ballabgarh, Northern India and urban community of Mumbai, India respectively.[14,15] Our study aimed at investigating the prevalence of cognitive decline as well as dementia and associated risk factors in the rural population of Varanasi district (Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

This study conducted on rural population of Chiraigaon block of Varanasi district of India from February 2007 to May 2007. This block has 80 villages, out of which 11 villages selected by random sampling method by using a random number table. Eleven camps were organized for elderly people in 11 randomly selected villages on predetermined dates.

Assessment tools

After obtaining informed consent from each subject, data were collected on a preformed performa. Hindi-mini-mental state examination (HMSE) was used in each subject. This is modified a modified version of mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in vernacular language with less emphasis on calculation ability, designed mainly for illiterate Hindi speaking population.[16] It is validated measure for evaluating cognitive decline. HMSE score of ≤23 has sensitivity of 81.3% and specificity of 60.2%.[17,18] In an elderly person with a HMSE score <23, detailed history and physical examination was done on a pretested performa. Clinical diagnostic criteria used was Diagnostic and statistical manual for Mental disorder fourth edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) for Alzheimer's Disease and Vascular dementia.[19]

Selection criteria

Elderly aged more than 60 years attending the camps were included in the study. Those having psychiatric illness, any serious illness or inability to communicate due to blindness, deafness or other problems were excluded.

Study design

The camps organized in 11 villages to examine elderly persons on preinformed date. Information about age, address, food habits, performance of activities of daily living, instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) were gathered by trained health staff. Physician did history taking and clinical examination. Elderly who got HMSE score ≤23 were evaluated further and those with confirmed cognitive and functional impairment were assigned diagnosis according to DSM-IV-TR criteria after ruling out any psychiatric illness or delirium.[19] International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria was used for sub-categorization of cases.[20]

Data analysis

Elderly persons interviewed, examined and data thus collected were analyzed with the help of SPSS statistical software (version 10 for Windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Chi-square test used for comparison of proportions. The difference considered significant if P < 0.05. The study had approval of Ethical Review Committee (Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India).

RESULTS

Sociodemographic profile

Survey evaluated 728 elderly of more than 60 years of age. Mean age of the population was 65.75 ± 5.78 years, with male having mean age of 66 ± 5.9 years and female 65 ± 5.7 years. In most of the villages, attendance of female in camps was more varying from 54% to 80% and it made 64.4% of total study population. Female to male ratio was 1.4:1. Literacy rate was very low varying from 2% to 20% with overall literacy rate of 12.8%. Male to female ratio in literate population was 2:1.

Nutritional status

In our study population, under-nutrition was very common, ranging from 25% to 70% in different villages accounting for overall prevalence of 39.3% when compared to obesity, which varied from 0% to 6% with an overall prevalence of 2.7%. Under-nutrition was more common in female (46.5%) than male (26.3%). Obesity was more common in male (4.6%) than female (1.7%). Females had lower mean body mass index (BMI) (20.0 ± 4.1) than males (20.66 ± 4.1). However, these observations lacked statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Activity of daily living

In our study, 7.2% elderly population have impaired performance of ADL; 4.3% in a single activity, 2.1% in two activities, and 0.8% in three activities. About 19.8% elderly have decreased IADL with 12.8% in a single activity, 6% in two activities, 1% in three activities and 0.1% in four activities.

Hypertension

In our study, 21.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 20.2-23.4) elderly had isolated systolic hypertension, 5.5% (95% CI: 4.8-6.2) elderly had isolated diastolic pressure and 53.8% (95% Cl: 51.6-56) elderly had both systolic and diastolic hypertension.

Cognitive status

The mean, median and 10th percentile of HMSE of our study population was 23.4, 24 and 17, respectively. In the study group, 42.9% of elderly had HMSE score lower than 23. Most of the elderly (28.3%) having low HMSE score had a score from 17 to 23 [Table 1].

Table 1.

HMSE score in study group

Table 2 depicts that literate people had statistically significant higher mean HMSE score (26.1 ± 3.9) than illiterate people (22.9 ± 4.9). Male have statistically significant higher mean HMSE score (23.9 ± 5.1) than female (23 ± 4.8). Underweight (22.7 ± 5.7) and obese (23.3 ± 4.9) had lower mean HMSE score than normal (23.6 ± 4.7) and preobese (23.1 ± 5.8). There was significant positive correlation between BMI and HMSE. Older people had lower mean HMSE score than relatively younger (60-69 years, 23.8 ± 4.8; 70–79 years, 22.3 ± 5.0; 80-89 years, 19.66 ± 6.6). There was significant negative correlation between age and HMSE score. Hypertensives had lower mean HMSE score than nonhypertensive (normal, 23.3 ± 4.9; Stage 1, 23.7 ± 5.0; Stage 2, 23 ± 5.4; Stage 3, 22.8 ± 4.1). Nevertheless, there was no significant correlation between blood pressure and HMSE. Person having lower HMSE score had statistically significant lower IADL, but not ADL. Literacy most strongly affected HMSE score followed by gender and age. Thus, cognitive functional status correlated with age, sex, literacy and nutritional status.

Table 2.

Comparison of HMSE score with various variables

There was significant positive correlation between HMSE and BMI as well as IADL. There were negative correlation of age with HMSE, BMI and IADL. ADL had a positive correlation with IADL, but no correlation with HMSE and other parameters. IADL had a positive correlation with HMSE and ADL, but negative correlation with age. HMSE has no correlation with systolic or diastolic blood pressure (SBP/DBP).

Dementia

Prevalence of dementia was 2.74% (male 2.70%, female 2.80%) in the study group with Alzheimer (male 1.5%, female 1.5%), vascular (male 1.2%, female 0.6%) and others (male 0%, female 0.6%). Most of the dementia people were of age group 65 years due to most of the population belong to this age group [Table 3]. There was no statistical significant difference in prevalence in different age group, due to the small number of the dementia patient. Dementia was more common in female (2.77%) than male (2.70%). Prevalence of Alzheimer dementia was equal in male and female (1.5%), vascular dementia was more common in male (1.2%) than female (0.6%). Others type of dementia was also more common in female (0.6%) than male (0.0%). However, these differences were not statistically significant. Table 4 shows that dementia was more common in illiterate (3.0%) than literate (1.1%). Prevalence of Alzheimer dementia was more common in illiterate (1.6%) than literate (1.1%) and vascular dementia too was more common in illiterate (0.9%) than literate (0.0%). Others type of dementia was also more common in illiterate (0.5%) than literate (0.0%). But these differences were also not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Dementia in relation to age group

Table 4.

Dementia in relation to literacy

DISCUSSION

Most of our study population was between the age group 60 and 70. This may be due to poor health facility, poor nutrition and camp interview methodology adapted. Distribution of age of the population, in other study was similar to our study. Female population was commoner in our study and also in other rural or urban studies.[14,21,22,23] Less occupation or more unmet needs of health facility in female may be cause of their more attendance in camps.

Literacy rate in our population was too low when compared with other rural and urban studies from India.[14,15,21,22] Eastern Uttar Pradesh is one of the most backward part of India, having high prevalence of illiteracy and poverty. Because poor and deprived people are more attracted toward free checkup camps, hence there may be some under representation of literate. Illiterates and female had lower mean BMI than literates and male respectively, but this was not statistically significant.

Hypertension

There was statistically no difference between genders or literacy status in relation with hypertension in our study. There was statistically no correlation with age. This may be because of most of study population were of age group 60-70 years and were undernourished. There was significant negative correlation of hypertension with BMI. It indicates that under-nutrition is not protective for hypertension and prevalence did not differ between sexes.

Cognitive status

In our study mean, median and 10th percentile of HMSE of study population were lower as compared to Indo-US rural population study figures of 25.4, 27 and 19, respectively.[15] This difference may be due to low literacy rate, dietary factors or more female participants. Observed range of HMSE score in nondemented elderly was similar to Indo-US rural population study.[15] In our study (literacy rate 12.8%), HMSE score was lower than 23 in 43%, in Shaji et al.[21] (literacy rate 89%) urban population study it was in 12% and in Vas et al.[14] urban study (literacy rate 68%) it was in 20%. A prospective based study from Sri Lanka done on elderly people presenting to tertiary care hospital showed prevalence of MMSE score ≤23 in 55.2% who received secondary education whereas 57.1% of elderly peoples who have not received secondary education had MMSE score <23.[14] This poor performance in our study group may be due to illiteracy, nutritional factor or poor development of cognition.[24] In rural illiterate population, HMSE has low positive predictive value if cut-off for dementia is 23. Our study suggest that cut-off of HMSE score should be 17 (10th percentile) for illiterate population.

Correlation and regression analysis

There was significant correlation between HMSE score and age (Pearson correlation coefficient is - 0.157, P < 0.01) in our study. Study of Mathuranath et al. has also shown that older people perform poorly on cognitive testing (HMSE scoring, Addenbrook's cognitive examination).[25] Male in our study had statistically significant higher mean HMSE score than female, which is similar to other published reports.[15] Literacy has strong correlation with MMSE/HMSE score, similar to other studies.[26,27,28,29]

There was no correlation between HMSE and SBP/DBP in our study, while Indo-US rural population study revealed significant correlation between HMSE and SBP or DBP in Ballabgarh in Northern India but not in Monongahella Valley, Pennsylvania, USA.[15] Their study showed for every 10 mmHg rise in SBP there was 10% reduction in cognition score and every 10 mmHg DBP rise associated with 13% reduction in cognition score. Framingham Study also showed decline in cognitive performance with every 10 mmHg rise in blood pressure. Antihypertensive treatment had been demonstrated to decrease cognitive decline.[30]

In our study, multivariate analysis showed that literacy (F = 2.5) was the most important factor, which affect the HMSE scoring followed by sex (F = 1.9), age (F = 1.8), blood pressure (F = 1.2), and BMI (F = 1.1). Mathuranath et al.'s study also showed education as the most important factor followed by age and sex.[25] There was significant correlation between HMSE and IADL (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.06, i.e. >0.01), people having lower HMSE score have lower ADL and IADL score (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.178, i.e. >0.01). There was significant positive correlation between BMI and HMSE score (Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.096, P < 0.01) in our study. It may be due to the high prevalence of under-nutrition in our study population. In contrast to this, other studies have shown a negative correlation between BMI and cognitive scores after adjustment for age, sex, educational level, blood pressure, diabetes, and other psychosocial covariables.[30,31] Both these studies were in an obese person. In our study, though the obese have lower mean HMSE score, but due to very low number of an obese person (2.7%) and high number of undernourished (39.3%), a significant positive correlation between HMSE and nutrition has been found.

Prevalence of dementia

The prevalence rate of 27.4/1000 in our study is well within the range of prevalence rates reported from other studies conducted in India.[12,13,14,15] A community-based study from Northern Italy reported prevalence of 9.8% in elderly more 60 years of age.[32] An epidemiological study from Brazil reported prevalence of 7.1% in elderly age ≥65 years.[33] A population-based study from urban area of Venezuela reported prevalence of 8.04% in people ≥55 years age.[34] Prevalence rate for dementia among elderly people reported from semi-urban area of Sri Lanka was 3.98%.[35] Low prevalence in India may be due under-recognition of cognitive impairment by family members, diet or cultural factors.[36,37]

Alzheimer's dementia was the most common (55%), followed by vascular dementia (30%) in our study. Alzheimer was common in both sexes, while vascular dementia was predominant in male. The relative proportion of Alzheimer's disease in the Indian studies ranged from 41% to 65% and the proportion of vascular dementia ranged from 22% to 58%.[12,13,14]

Risk factors

One of the consistent findings across various studies is that the prevalence of dementia increases proportionately with age.[38] Our study also confirmed this finding. Female sex and illiterate people are more predisposed to dementia.[38] We also found that people with dementia more often had under-nutrition and decreased IADL. Despite having illiteracy and under-nutrition, the lower rate of dementia may be explained by underrepresentation of very elderly, lower life expectancy or due to dietary factors, which need further work-up.

Limitations

Main limitation of this study is that it is a camp-based study, so result cannot be generalized to whole rural population. In addition, assessment of risk factors was based on the retrospective account of caregivers.

CONCLUSION

There was high rate of low cognitive scoring (43%) in this study even by HMSE but the prevalence of dementia was not high (27/1000). There was significant difference between literacy, age, sex, and poor cognitive scoring. There was positive correlation between BMI and cognitive scoring; due to high degree of malnutrition. Alzheimer's disease was the most common cause of dementia, followed by vascular dementia. Identification of risk factors such as illiteracy and under-nutrition points towards some possible methods of intervention to reduce the total prevalence of dementia in the community. Cut-off for HMSE score for diagnosing cognitive decline in illiterate people should be <17.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thanks the staff of Department of Community Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University for their generous help in organizing these camps.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaji KS, Jithu VP, Jyothi KS. Indian research on aging and dementia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S148–52. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaji KS, Iype T, Praveenlal K. Dementia clinic in general hospital settings. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:42–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.44904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das SK, Pal S, Ghosal MK. Dementia: Indian scenario. Neurol India. 2012;60:618–24. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.105197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganguli M. Depression, cognitive impairment and dementia: Why should clinicians care about the web of causation? Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(Suppl 1):S29–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dias A, Patel V. Closing the treatment gap for dementia in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(Suppl 1):S93–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirk-Sanchez NJ, McGough EL. Physical exercise and cognitive performance in the elderly: Current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:51–62. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S39506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galimberti D, Scarpini E. Progress in Alzheimer's disease research in the last year. J Neurol. 2013;260:1936–41. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6921-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramlall S, Chipps J, Pillay BJ, Bhigjee AL. Mild cognitive impairment and dementia in a heterogeneous elderly population: Prevalence and risk profile. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2013;16:6. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v16i6.58. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheffield KM, Peek MK. Changes in the prevalence of cognitive impairment among older Americans, 1993-2004: Overall trends and differences by race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:274–83. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sosa AL, Albanese E, Stephan BC, Dewey M, Acosta D, Ferri CP, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and impact of mild cognitive impairment in Latin America, China, and India: A 10/66 population-based study. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajkumar S, Kumar S, Thara R. Prevalence of dementia in a rural setting: A report from India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:702–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199707)12:7<702::aid-gps489>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajkumar S, Kumar S. Prevalence of dementia in the community-A rural-urban comparison from Madras, India. Aust J Ageing. 1996;15:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaji S, Promodu K, Abraham T, Roy KJ, Verghese A. An epidemiological study of dementia in a rural community in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:745–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vas CJ, Pinto C, Panikker D, Noronha S, Deshpande N, Kulkarni L, et al. Prevalence of dementia in an urban Indian population. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13:439–50. doi: 10.1017/s1041610201007852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandra V, Ganguli M, Pandav R, Johnston J, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in rural India: The Indo-US study. Neurology. 1998;51:1000–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, et al. A Hindi version of the MMSE: The development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–77. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsolaki M, Iakovidou V, Navrozidou H, Aminta M, Pantazi T, Kazis A. Hindi Mental State Examination (HMSE) as a screening test for illiterate demented patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:662–4. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200007)15:7<662::aid-gps171>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaji S, Bose S, Verghese A. Prevalence of dementia in an urban population in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:136–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llibre Rodriguez JJ, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Guerra M, Huang Y, Jacob KS, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America, India, and China: A population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2008;372:464–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saldanha D, Mani MR, Srivastava K, Goyal S, Bhattacharya D. An epidemiological study of dementia under the aegis of mental health program, Maharashtra, Pune chapter. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:131–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigo C, Perera S, Adhikari M, Rajapakse A, Rajapakse S. Cognitive impairment and symptoms of depression among geriatric patients in a tertiary care unit in Sri Lanka. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:279–80. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.71000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathuranath PS, Cherian JP, Mathew R, George A, Alexander A, Sarma SP. Mini mental state examination and the Addenbrooke's cognitive examination: Effect of education and norms for a multicultural population. Neurol India. 2007;55:106–10. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.32779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cournot M, Marquié JC, Ansiau D, Martinaud C, Fonds H, Ferrières J, et al. Relation between body mass index and cognitive function in healthy middle-aged men and women. Neurology. 2006;67:1208–14. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238082.13860.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahlke AR, Curtis LM, Federman AD, Wolf MS. The mini mental status exam as a surrogate measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:615–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2712-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgado J, Rocha CS, Maruta C, Guerreiro M, Martins IP. Cut-off scores in MMSE: A moving target? Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:692–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Jeong JH, Han SH, Ryu HJ, Lee JY, Ryu SH, et al. Reliability and validity of the short form of the literacy-independent cognitive assessment in the elderly. J Clin Neurol. 2013;9:111–7. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farmer ME, White LR, Abbott RD, Kittner SJ, Kaplan E, Wolz MM, et al. Blood pressure and cognitive performance. The Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:1103–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kretsch MJ, Green MW, Fong AK, Elliman NA, Johnson HL. Cognitive effects of a long-term weight reducing diet. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:14–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferini-Strambi L, Marcone A, Garancini P, Danelon F, Zamboni M, Massussi P, et al. Dementing disorders in North Italy: Prevalence study in Vescovato, Cremona Province. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:201–4. doi: 10.1023/a:1007340727385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrera E, Jr, Caramelli P, Silveira AS, Nitrini R. Epidemiologic survey of dementia in a community-dwelling Brazilian population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:103–8. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molero AE, Pino-Ramírez G, Maestre GE. High prevalence of dementia in a Caribbean population. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:107–12. doi: 10.1159/000109824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Silva HA, Gunatilake SB, Smith AD. Prevalence of dementia in a semi-urban population in Sri Lanka: Report from a regional survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:711–5. doi: 10.1002/gps.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prince MJ. The 10/66 dementia research group-10 years on. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(Suppl 1):S8–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albanese E, Dangour AD, Uauy R, Acosta D, Guerra M, Guerra SS, et al. Dietary fish and meat intake and dementia in Latin America, China, and India: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:392–400. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathuranath PS, Cherian PJ, Mathew R, Kumar S, George A, Alexander A, et al. Dementia in Kerala, South India: Prevalence and influence of age, education and gender. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:290–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]