Abstract

Dhat syndrome as a clinical entity has been rarely described in females. Ethnographic studies suggest that as in males, whitish vaginal discharge in females is also associated with depressive and somatic symptoms and many women with symptoms of whitish discharge attribute their depressive and somatic symptoms to the whitish discharge. In this report, we describe two female patients who presented with psychiatric manifestations also with somatic symptoms and attributed their somatic complaints to whitish vaginal discharge. In this background, we discuss whether this entity requires nosological attention and what criteria can be used to define the same.

Keywords: Dhat syndrome, females, vaginal discharge

INTRODUCTION

Dhat syndrome is characterized by preoccupation of loss of semen, usually in a young man, during micturition, while straining to pass stools or in the form of night falls. The preoccupation of loss of semen is also associated with vague and multiple somatic and psychological complaints such as fatigue, listlessness, loss of appetite, lack of physical strength, poor concentration, and forgetfulness. Some patients may have accompanying anxiety or depressive symptoms and sexual dysfunction, which are usually psychological in nature. The patients usually attribute all their symptoms (somatic symptoms and sexual dysfunction) to the passage of semen.[1]

Although Dhat syndrome has been described in males, some researchers/clinicians have also talked of a female equivalent of this syndrome. Chaturvedi[2] for the first time equated the symptoms of vaginal discharge in females with Dhat syndrome in males. Singh et al.[3] described a case of female Dhat syndrome, who hailed from a conservative family, presented with complaints of aches and pains, headaches and poor concentration, which she attributed to the passage of “Dhat” in urine. Besides this, there are few studies, which have evaluated patients with vaginal discharge and have tried to evaluate the understanding and attribution of such symptoms by the patients.[4,5,6] In this report, we present two cases akin to Dhat syndrome in females and discuss the existing literature, which has described Dhat syndrome equivalent in females.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 33-year-old married, housewife, belonging to middle socioeconomic status from a rural background, who was premorbidly well-adjusted presented with an insidious onset illness characterized by multiple aches and pains since last 8 years. Detailed evaluation of history revealed that about 8 years back she developed whitish vaginal discharge, which was thick, transparent fluid, nonfoul smelling and intermittent initially, which later increased in frequency. Since her early days, she knew from her friends and relatives that “passage of whitish vaginal discharge is associated with the loss of energy and weakness,” and hence she started remaining distressed. Initially, she developed heaviness of head and over the next few months developed pain in the hands, forearm, elbow, knees, and lower limbs. Also would feel tired for the most time of the day. She discussed about her problem with her friends and relatives, who voiced their concern and told her that these symptoms would persist through her life. This led to increase in her distress and somatic symptoms. Over the years, she observed that symptoms of vaginal discharge would increase few days prior to menses and also noted that any change in the passage of vaginal discharge that is, reduction in discharge would be associated with relief or reduction in aches and pains. Further, she observed that symptoms of vaginal discharge would slightly reduce after intercourse that is, the amount of fluid would reduce for 3-4 days and would be associated with slight improvement in pain symptoms too.

Gradually, the vaginal discharge became more persistent and her distress and somatic symptoms increased. She visited many faith healers, traditional healers, physicians, gynecologists and was suggested various treatments, but did not perceive any improvement. She would frequently self-medicate with analgesics, but did not perceive any improvement.

Over the years, her symptoms became more severe. Three months prior to presentation to our outpatient, she developed fluctuating sadness of mood, lethargy, anhedonia, poor attention concentration, depressive ideations (ideas of hopelessness, worthlessness), further increase in distress due to vaginal discharge, decreased sleep, and appetite. Psychosocial history revealed that since her marriage she had interpersonal relationship problems with her mother-in-law and sister-in-law.

She was evaluated in different treatment settings. In the gynecology services of the hospital, she was evaluated for dysmenorrhea, prolapse of the uterus and lower genital tract infection, but no abnormality was detected. In the medical outpatient services she was evaluated for fibromyalgia, anemia, hypothyroidism, but all the investigations did not reveal any abnormality. She was treated with fluoxetine and amitriptyline from the medical outpatient, but did not perceive any improvement. Following this, she was referred to psychiatric outpatient. After detailed evaluation diagnoses of somatoform pain disorder and moderate depressive episode without somatic symptoms were considered. She was treated with duloxetine up to 60 mg/day along with psychological intervention for 6 weeks. The psychological intervention involved sex education, acknowledging her symptoms, addressing her explanatory models, explaining physiological nature of vaginal discharge, explaining psychological nature of her somatic symptoms, addressing the interpersonal relationship problems with mother-in-law and sister-in-law and limiting her help seeking (i.e. doctor shopping). Over the period of 6 weeks, she gradually improved, and her depressive symptoms resolved completely. Her preoccupation and distress with vaginal discharge also reduced, which led to partial benefit in symptoms of sadness and aches and pains.

Case 2

X, a 19-year-old woman presented with obsessive thoughts about contamination and compulsive cleaning in the form of bathing and washing since 1.5 years. On inquiry it emerged that the patient had vaginal discharge since last 2 years, and she characterized it as “Dhat.” The discharge was whitish, mucoid to watery (depending on the time period of her menstrual cycle), nonfoul smelling, not associated with any burning sensation during micturition. She denied any form of sexual fantasy/stimulation that was related to this discharge. Since the onset of this discharge, she believed that “Dhat” was “dirty” and also that such discharge was abnormal. In addition, she began to feel low in energy, would have body aches, would feel that her skin had lost its glow and her hair had lost its shine. She believed that this was due to the passage of “Dhat” and this belief was further strengthened following discussions with other female relatives who confirmed her beliefs. Her menstrual cycle was regular (cycles lasting 30 days, with 6 days of menstrual flow) and patient denied any form of sexual contact or masturbation.

Since the onset of symptoms patient had been visiting multiple traditional healers, local doctors and gynecologists for treatment of “Dhat” and other symptoms, but investigations did not reveal any abnormality and medication did not provide any relief. In addition, she was told by doctors on a few occasions that this discharge was normal, but she did not accept the same, as she believed that numerous others in her society could not be wrong.

About 6 months after the onset of symptoms of vaginal discharge (i.e. 1½ year back), she also began to experience repetitive, intrusive, anxiety provoking thoughts regarding her private parts and hand being dirty, following which she would repeatedly wash the same. Despite acknowledging her thoughts to be absurd, she would be unable to control herself. She however attributed these symptoms to Dhat as well. She would frequently ask female relatives/acquaintances if they too had such symptoms of vaginal discharge, and would constantly be preoccupied with the vaginal discharge, loss of her vigor, vitality and her “mental peace” due to the same. Gradually her symptoms increased, and she developed obsessive doubts, especially involving washing and checking, which involved all spheres of her life and led to marked psychosocial dysfunction. Following the increase in obsessive compulsive symptoms to such an extent that she was unable to perform her daily chores and self-care, she sought psychiatric consultation. She was diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), mixed thoughts and acts and Dhat syndrome. She was started on sertraline 200 mg/day. Psychoeducation sessions were taken regarding female reproductive and genital anatomy and physiology and her experiences were normalized. All this led to improvement in anxiety, health related concerns and preoccupation with vaginal discharge. Her symptoms of OCD also reduced significantly that is, by 80%.

DISCUSSION

The evidence of existence of female equivalent of Dhat syndrome comes from various studies from south Asia. In an ethnographic study from North India, Trollope-Kumar[5] observed that loss of genital secretion is a cause of concern for women too. The women usually present with complaints of safed panni (white water), dhatu or swed pradhar. They are worried about the loss of genital secretion and report that loss of secretions was associated with progressive weakness in the body. These women also had associated symptoms of vague somatic manifestations in the form of burning hands and feet, dizziness, backache, and weakness. Other ethnographic studies also provide credence to these observations and suggest that weakness attributed to white discharge is associated with physical weakness, mental weakness, and sexual weakness.[6] With regards to attribution or cause of whitish discharge studies suggests that patients usually attribute it to multitude of factors like undergoing tubectomy and faulty diet.[5] Trollope-Kumar[5] also observed that many patients and local health care professionals (e.g. dai) were worried about safed panni because they believed that “100 drops of blood was required to make drop of safed panni.” Further clinical evaluation of these females suggest little evidence of infection and the amount of discharge complained seems no more than normal physiological discharge.[5] Some of the reports from other parts of Asia also suggest the existence of similar syndrome. An anthropologist from Sri Lanka also noted problems related to dhatu in both men and women. It is suggested that the dhatu is expelled from the female's body in the form of whitish, odorless discharge and is associated with features of burning hands and feet, dizziness, and joint pain.[7]

Other studies which have evaluated the patients with whitish discharge or leukorrhea in different set ups have also suggested the existence of Dhat syndrome equivalent in women. In a study from South India, Chaturvedi[2] evaluated women presenting with leukorrhea and reported depression in about half of their patients and described the clinical picture as “psychoasthenic syndrome” and considered it to be akin to “Dhat syndrome” in males. Other authors have also shown the link between somatic symptoms and common mental disorders with vaginal discharge[8,9,10,11] and some consider leucorrhea to be a somatic idiom of expression of depression in South Asia.[12]

However, it can always be questioned that the leukorrhea may be actually associated with infective pathology and the clinical symptoms of weakness and backache, etc., may be secondary to the infection. To overcome this in a large sample study from Goa, authors studies women with vaginal discharge and evaluated the association of same with biological (infectious and reproductive), psychological (depression and somatoform disorders), and social (gender-based violence and poverty) factors.[10,11] The authors found that psychosocial factors, in the form of presence of common mental disorders or symptoms of somatoform disorders were most strongly associated with the complaint of vaginal discharge and reproductive tract infections had little association with vaginal discharge. The common causal models for vaginal discharge held by the patients were stress and emotional factors (36.6%), excess heat in the body (35.2%), and infection (30.5%). Further, in-depth interviews with these women revealed that most women linked the onset of their complaint or its causation with significant reproductive events in their lives, notably menarche, pregnancy, childbirth, and sterilization; especially menarche (n = 16). Other causative factors included the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices. Other causative factors which were linked to vaginal discharge were weakness, tension, hot and spicy foods and hot weather. With regards to tension and weakness, bidirectional relationship was suggested.[13] The interviews also suggested women's perception of link between vaginal discharge and somatic complaints.[13] It was also seen that women attributed the vaginal discharge to unwanted sex or concept of “heat” arising from the sexual act itself, which led to vaginal discharge. Further linking vaginal discharge with “hot-cold balance” reflects the importance of ayurvedic concepts in formation of these beliefs.[13] In terms of characteristics of the vaginal discharge, the most common color of discharge was white (82.5%) followed by yellow (14.1%) and was odorless in more than half of the patients (53.2%). About three-fifth (61.8%) of the women reported that the vaginal discharge occurred during the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle.[11]

The two cases described in this report also had preoccupation and distress associated with vaginal discharge and had associated somatic and depressive symptoms. The explanatory models held by patients were also very typical of those described in literature for patients with abnormal vaginal discharge.

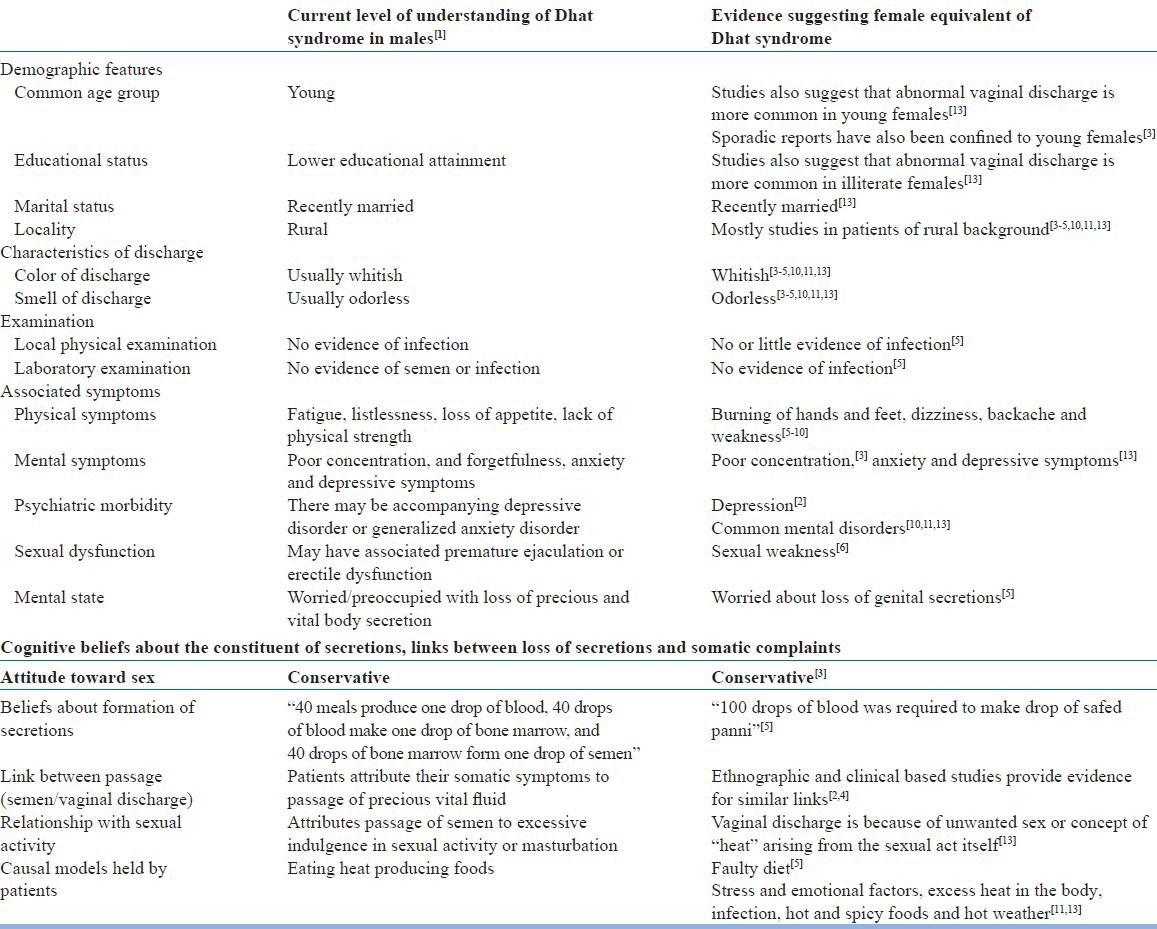

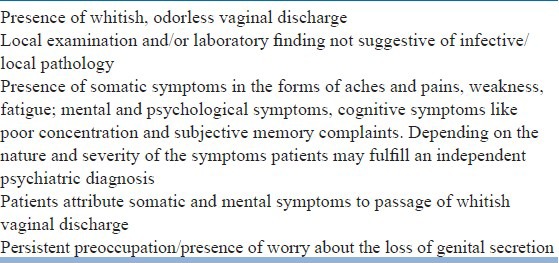

From the review of literature presented in this report and the description of typical cases as presented in this report, it is evident that there is a merit in considering a female equivalent of Dhat syndrome, as reported in males. The case for this becomes further stronger, when one tries to compare the clinical description of cases of vaginal discharge with findings reported in patients of Dhat syndrome in males. As evident from Table 1, a significant overlap appears between the both. Further, if one tries to rely on the traditional concepts that is, those of Ayurveda, many of the links and attributions associated with vaginal discharge are similar to those reported for Dhat syndrome in males.[5] Considering this overlap, it can be said that definitely there is a female equivalent of Dhat syndrome and there is a need for clinical characterization of the same. Considering the lack of definition, we propose operational definition [Table 2] for Dhat syndrome in females. It is expected that evolving this operational definition will help in proper identification of this entity and would pave the way for further research in this area. There is also a need to develop treatment modules for this disorder so as to reduce morbidity.

Table 1.

Evidence for clinical entity of female Dhat syndrome

Table 2.

Operational criteria for Dhat syndrome in females

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Avasthi A, Grover S, Jhirwal OP. Dhat Syndrome: A culture-bound sex related disorder in Indian subcontinent. In: Gupta S, Kumar B, editors. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2nd ed. New Delhi, India: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 1225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi S. Psychasthenic syndrome related to leucorrhea in Indian women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 1988;8:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh G, Avasthi A, Pravin D. Dhat syndrome in a female - A case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 2001;43:345–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS, Issac MK, Sudarshan CY. Somatization misattributed to non-pathological vaginal discharge. J Psychosom Res. 1993;37:575–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90051-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trollope-Kumar K. Cultural and biomedical meanings of the complaint of leukorrhea in South Asian women. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:260–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang R, Bang A. Perceptions of white vaginal discharge. In: Gittelsohn J, Bentley M, Pelto P, Nag M, Pachauri S, Harrison A, et al., editors. Listening to Women Talk About their Health. New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications; 1994. pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obeyesekere G. The impact of ayurvedic ideas on the culture and the individual in Sri Lanka. In: Leslie C, editor. Asian Medical Systems. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gittelsohn J, Bentley ME. New Delhi: Ford Foundation; 1994. Listening to Women Talk about their Health: Issues and Evidence from India. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatti LI, Fikree FF. Health-seeking behavior of Karachi women with reproductive tract infections. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:105–17. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel V, Pednekar S, Weiss H, Rodrigues M, Barros P, Nayak B, et al. Why do women complain of vaginal discharge? A population survey of infectious and pyschosocial risk factors in a South Asian community. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:853–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Weiss HA, Kirkwood BR, Pednekar S, Nevrekar P, Gupte S, et al. Common genital complaints in women: The contribution of psychosocial and infectious factors in a population-based cohort study in Goa, India. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1478–85. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V, Oomman NM. Mental health matters too: Gynecological morbidity and depression in South Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 1999;7:30–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel V, Andrew G, Pelto PJ. The psychological and social contexts of complaints of abnormal vaginal discharge: A study of illness narratives in India. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]