Abstract

Background:

The science of wound healing is advancing rapidly, particularly as a result of new therapeutic approaches. The wound healing effect of different herbal ointments have been enormous and are in wide practice these days.

Aim:

To evaluate the efficacy of Panchavalkala cream over wound debridement (wound infection and microbial load).

Materials and Methods:

Ghanasatwa (water extract) of the individual drugs of Panchavalkala was prepared and the extract formulated as herbal ointment. This was used to treat patients of infected chronic non healing wounds. The signs and symptoms of infection were graded before and during the course of treatment. Tissue biopsy to estimate the microbial load prior to and during the course of treatment was done.

Results:

The clinical symptoms like Slough, swelling, redness, pain, discharge, tenderness, and malodor in wounds showed statistically significant reduction following treatment. The microbial load of the wounds was also reduced significantly.

Conclusion:

In most of the cases, there was a progressive reduction in the microbial load with time, during the course of treatment indicating the efficacy of the formulation in reducing the microbial load and thus controlling infection, facilitating wound healing.

Keywords: Chronic non healing wounds, infection, microbial load, Panchavalkala, Vrana Shodhana

Introduction

Certain factors that influence wound healing include bacterial infection, nutritional deficiency, drugs, site of wound etc., All chronic wounds intrinsically contain bacteria, and the process of wound healing can still occur in their presence. It is, therefore not the presence of bacteria[1] but their interaction with the host that determines the organisms’ influence on chronic wound healing. However, the relative number of micro-organisms and their pathogenicity, in combination with host response and factors, such as immunodeficiency, dictate whether a chronic wound becomes infected or shows signs of delayed healing.

Wound infection is defined as the presence of replicating microorganisms within a wound with a subsequent host response that leads to delayed healing. Because of this it is important that infection is recognized as early as possible. The signs and symptoms of local infection are redness (erythema), warmth, swelling, pain, and loss of function. Foul odor and pus may accompany this. Eventually, the local bacterial burden will increase further and become systemically disseminated resulting in sepsis, which if not actively treated could progress to septicemia and multi-organ failure.[2,3]

There are several factors known to affect the bacterial burden of chronic wounds and increase the risk of infection. These include the number of microorganisms present in the wound, their virulence, and host factors. Experimental studies have demonstrated that regardless of the type of microorganism, impairment of wound repair may occur when there are more than 1 × 105 organisms per gram of tissue.[4,5,6,7] Hence, it becomes essential that a drug used to control the wound infection must necessarily reduce the microbial load.

In the Indian context, the formal descriptions of wound care have been vividly elaborated in the three great treatises (Brahatrayi) of Ayurveda viz. Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita and Astanga Sangraha. These documents not only describe Vrana (various types of wounds) but they also present their systematic classification along with their management including various systemic and local drugs and preparations. Sushruta, the father of Indian surgery in 1000 BC has elaborated the concept of Vrana. He not only gave an elaborate description of various types of wounds, but also presented a descriptive etiopathogenesis of wounds along with their management. Sixty different procedures for the management of wounds along with numerous herbal drugs, which he had used as local applicant for curing them, have been described. His techniques are broadly classified as Vrana Shodhana and Vrana Ropana. He advocated external application of various drugs under these categories. One among them is the Nyagrodhadi Varga mentioned in Vrana Ropana Kashaya which includes Panchavalkala.[8] Clinically, Panchavalkala i.e. group of barks of five trees – Vata (Ficus bengalensis L.), Ashwatha (Ficus religiosa L.), Udumbara (Ficus glomerata Roxb.), Plaksha (Ficus lacor Buch-Ham.), Parish (Thespesia populenea Soland. ex corea.), is found to be very effective in controlling wound infection when used externally in different forms, which suggests its action on Vrana Shodhana as well. Bearing this in mind, in the present study, the effect of Panchavalkala cream over wound debridement with special reference to wound infection and the microbial load was estimated so as to prove its efficacy on Vrana Shodhana.

Materials and Methods

The study employed a single arm before-after clinical trial design. Patients who met entry criteria with chronic wounds were assessed for signs and symptoms of localized infection, and viable wound tissue specimens were obtained for quantitative microbiological analyses prior to and during the course of the treatment. The approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) was taken (Ref. No. IMS/I 43/2009/301906) and informed consent from each patient obtained.

Setting and sample

The study population consisted of 50 subjects with nonmalignant chronic wounds. The outpatient department of the Department of Surgery in the Ayurvedic and modern wings, “Wound Clinic” under the modern wing and the Department of Microbiology in the same campus served as settings for the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The criteria of selection of cases of wounds were based on the symptomatology presented by the patients in accordance to description by Sushruta on Dushta Vrana (non-healing ulcers). Patients diagnosed to have chronic non healing wounds which were infected, were randomly selected, irrespective of age, sex, associated disease etc., Patients without infection and malignant wounds were excluded from the study.

Test drug - Panchavalakala cream

Method of preparation of Ghanasatwa (dry aqueous extract) from Panchavalkala drugs

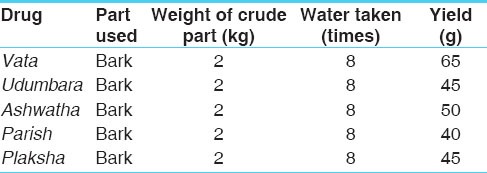

Fresh drugs were collected and cleaned with normal water and then dried for 10–15 days. They were then cut to small pieces (Yawakuta Choorna). Then decoction (Kwatha) of the individual drugs were prepared by adding 8 times of water, boiling at 100°C until the water reduced to ¼ of its initial volume, then it was filtered using a clean cloth and the liquid portion was separated from the Yawakuta of the drug. It was re-filtered to avoid presence of impurities. This liquid portion was kept in hot water bath for few hours and when it became concentrated; it was kept in incubator at 40°C for 4–5 days. When the drug dried up completely, it was powdered and stored in air tight containers. This powder is nothing but the Ghana Satwa or the aqueous extract of the drug. The yield of the individual drugs of Panchavalkala is depicted in Table 1. Each of the drugs was neatly labeled.

Table 1.

Yield of Ghanasatwa of Panchavalkala

Finally 40 g of each drug was taken and mixed to prepare a homogenous Panchavalkala extract.

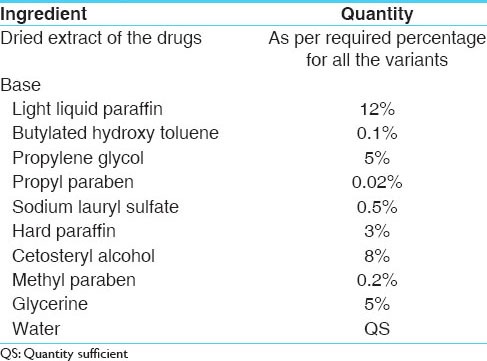

Method of preparation of the cream

Composition of the test drugs were depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition of the Panchavalkala cream

Step 1

Take light liquid paraffin, glycerine, butylated hydroxy toluene, methyl paraben and propyl paraben in stainless steel (SS) container. Gently heat while stirring until butylated hydroxy toluene, methyl paraben and propyl paraben fully dissolve.

Step 2

Take water in separate SS container and add Sodium Lauryl Sulphate (SLS). Heat gently until SLS dissolve. Add the required extract into the water and heat gently till it get fully dissolved. Filter the solution with 100# filter cloth.

Step 3

Heat hard paraffin and cetostearyl alcohol in separate container (at temp 80°C) to melt.

Step 4

Attach step 2 solution with homogenizer and mix properly. Add the step 1 solution into the container with step 2. After thoroughly mixing, mix the step 3 (melted part) into step 2. Solution will become viscous and formation of cream will start. After cooling smooth cream will form. Total mixing time is 12 min.

Thus prepared Panchavalkala cream in ointment form was packed in tubes.

Posology

Panchavalkala cream was administered by local application once daily for dressing of the wound until complete debridement. Surgical debridement was done as per the need. Internally, analgesics were administered whenever necessary.

Microbiological study

Wound biopsies were processed at a single microbiology laboratory. The tissue specimens were collected under strict sterile conditions. Tissue biopsy was done which is removal of a piece of tissue with a scalpel or by punch biopsy. Before performing a tissue biopsy for wound culture, the area was cleansed with sterile solution which did not contain antiseptic. The biopsy was performed and pressure applied to the area to control bleeding. The biopsy tissue was promptly transported to the laboratory where it was weighed, ground and homogenized, serially diluted in test tubes and plated onto blood agar. Plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 40°C for 24 h. Because dilutions were based on weight of tissue, the plate count multiplied by the dilution factor yielded the number of organisms per gram of tissue.

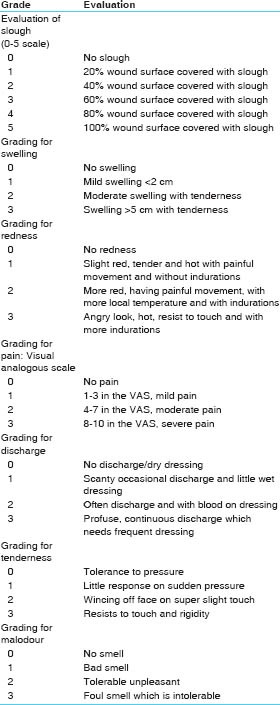

Criteria for assessment

The primary study variables were the following:

1. Clinical signs and symptoms of infection

A clinical signs and symptoms checklist was developed to measure the presence or absence of chronic wound infection (that is- slough,[9] swelling,[10] redness, discharge, malodor,[11] pain and tenderness[12]). A grading system for each sign and symptom was prepared under the guidance of wound experts.

The grades were noted before and after the treatment. Weekly assessment was done in all the patients and the grades of each of the above mentioned signs and symptoms were assessed during the course of treatment.

2. Culture findings based on viable wound tissue specimens.

Wound culture using tissue biopsy to assess the microbial load was done thrice during the course of treatment. The biopsy was taken at the first visit, which is prior to the treatment and the load assessed. The procedure was followed after 2 weeks and 4 weeks of treatment. The change in the microbial load prior and during the course of treatment was assessed.

For statistical evaluation, the above readings were divided into three grading - mildly infected (values with 105 and 106 dilutions), moderately infected (values with 107 and 108 dilutions) and severely infected (values > 108) given with Grades 1–3 respectively.

The statistical values were then inferred using Student's t-test (paired).

Observations

Among the 50 subjects, males outnumbered the females (71.4%), majority of them were found in the age group of 41–50 years (40%). Almost half the subjects belonged to the labor class (50%). In 64.3% of the subjects, the mode of onset was sudden and in 35.7% the duration of wound was between 3 and 6 months. About 83.3% of subjects complained of pain out of which 26.2% had mild pain, 35.7% moderate pain and 21.4% had severe pain. Nearly 88.1% of the subjects observed discharge out of which 52.4% had serous discharge, 19.0% sero-sanguineous and 16.7% had purulent discharge. The shape of the wound was irregular in 47.6% and 54.8% of the wounds were in the foot. 88.1% of the subjects had single wound and 11.9% had multiple wounds. About 14.3% observed glossy red and edematous areas surrounding the wound, whereas 11.9% observed eczematous and pigmented surroundings. The remaining 73.8% were either normal or in other forms. Based on the type of the wound 38.1% of the subjects had diabetic wound where as 35.7% had traumatic. 2.4% had tropical, 9.5% each had venous and arterial wounds. The remaining 4.8% of the subjects had leprotic wound.

Following observations were made on the 50 subjects based on their grade of slough - Grade 0–7.1%, Grade 1: 11.9%, Grade 2: 14.3%, Grade 3: 14.3%, Grade 4: 11.9% and Grade 5: 40.5%. More than half of the 50 subjects (59.5%) were classified under the Grade 0 category of swelling, where as 28.6% were under Grade 1 category. 4.8% of the subjects were classified under Grade 2 category and 7.1% under the Grade 3 category. 85.7% of the 50 subjects had Grade 0 category of redness around the wound, 11.9% had Grade 1 category of redness, and 2.4% had Grade 2 redness. There were no subjects with Grade 3 redness. Since an average of 16.7% of the 50 subjects did not complain of pain, out of the rest, 26.2% had mild pain, 35.7% had moderate pain whereas 21.4% had severe pain. Similarly, since an average of 11.9% of the 50 subjects did not complain of discharge, out of the rest, 52.4% had serous discharge, 19.0% had sero-sanguineous discharge whereas 16.7% had purulent discharge. Nearly about half of the 50 subjects (47.6%) had no tenderness. Of the rest, 35.7%belonged to Grade 1 category, 2.4% to Grade 2 category and remaining 14.3%to Grade 3 category. Of the 50 subjects, 19.0% did not have any malodor, 40.5% had Grade 1 malodor, 26.2% had Grade 2 and 14.3% had Grade 3 malodor.

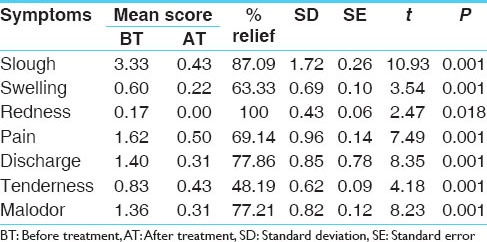

Results

Slough, swelling, redness, pain, discharge, tenderness, and malodor in wounds showed statistically significant reduction following treatment [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effect of therapy on different signs and symptoms

Effect of therapy on microbial load

The average microbial load of the wounds was reduced from 1.80 to 0.32 showing marked improvement with mean difference of 1.48 ± 0.71 and t value 10.362, which is statistically significant (P = 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Effect of therapy on microbial load

From the above observations, it is clear that Panchavalkala cream is effective in reducing the microbial load of the chronic non healing wounds. Anyhow the action on individual variety of pathogens cannot be explained as only quantitative assessment of the load was included in the study.

Discussion

Effect of therapy on individual symptoms:

Pain

Considering the mode of action by the Rasa, Panchavalkala must have been Vatakara and hence increase the Ruja (pain) which is predominantly due to Vata. But the effect of the drug on Ruja is found to be highly significant. This might due to the action of the Guna (Property). Having Guru (heavy) Guna it is supposed to be Vatahara and thus might have decreased the Ruja.[13]

Discharge

Panchavalkala is a drug with Kashaya Rasa (astringent taste) and by the action of the Rasa; it acts as a Stambhaka (arresting) and Grahi (that holds).[14] It also must be Atitwak Prasadaka (cleanses the skin and removes all the dirt from here).[15]

Due to all these properties, it must have reduced the Srava (discharge). The Stambhana effect might also be attributed to the Sheeta Veerya (cold in potency) of the drug.[16]

Redness

Panchavalkala are considered to be Pittaghna, that is both by the action of Rasa (taste) and Veerya (potency) they are Pittahara and therefore they must decrease the Raga (redness), which is mainly due to Pitta. By virtue of its Kashaya Pradhana Rasa, it must have acted as Rakta Shodhaka (blood purifier). Pitta Shamana, Varnya (giving color) and Twak Prasadana (purity/brightness of skin) actions aided to improve the skin color by improving the local blood circulation.

Swelling

In case of Panchavalkala, which is considered to be good Shothahara (that which reduces swelling), due to the Kashaya Rasa of the drug it acts with Peedana (act of squeezing), Ropana (heal) and Shodhana (curative effect) property. Due to these properties, it destroys or liquefies the accumulated substances and hence minimizes the swelling. Furthermore, the drug is Rooksha (dry) and Kaphahara. Even due to this, Shopha, which is Kaphaja, gets reduced. Moreover the Lekhana (scraping), Kledahara (arresting Dampness), Chedana (destroying/removing) and Raktashodhaka (blood purifier) properties of Kashaya Rasa also will facilitate the debridement of the slough.

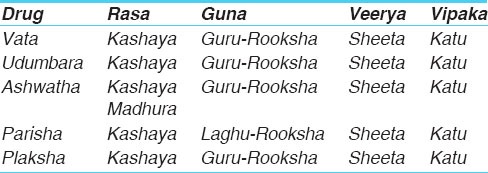

Pharmacological action of Panchavalkala

Pharmacological action of Panchavalkala proves that all the five drugs of Panchavalkala are found to have anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antimicrobial, and wound healing properties.[17,18,19,20,21,22] The pharmacodynamic properties of Panchavalkala are stated in Table 5.

Table 5.

Pharmacodynamic properties of Panchavalkala

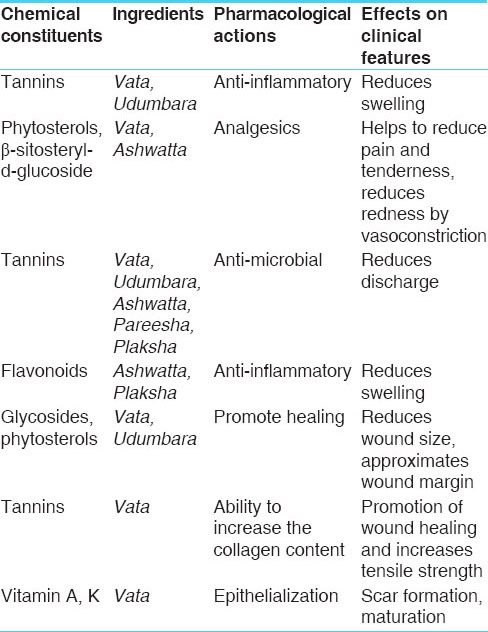

Chemical constituents of the trial drug-Panchavalkala cream are explained in Table 6. Tannins are known antioxidants and blood purifiers with anti-inflammatory actions.[23]

Table 6.

Chemical constituents of the trial drug-Panchavalkala cream

As the oxidation process hampers the wound healing, antioxidants protect the tissue from the oxidative damage. The flavonoids rich fraction of the bark of Pareesha, Vata, Ashwatha and Plaksha has proven to possess good in vitro antioxidant property. Tannins, phytosterols and flavonoids are anti-inflammatory; hence they prevent the prolongation of the initial phase. They also reduce the pain, tenderness, redness, swelling like features and thus help to control the infection.[24] Tannins and phytosterols promote the healing process by wound contraction with increased capillary formation. Tannins have been reported to possess ability to increase the collagen content, which is one of the factors for promotion of wound healing.[25] Vitamin A and K are essential for epithelialization promoting the healing.

The statistical data as stated above has revealed highly significant results in reducing the slough, swelling, redness, pain, discharge, tenderness, and malodour. Moreover, the tissue biopsy taken for the estimation of the microbial load supported the clinical study showing highly significant results for reduction of the load prior to and after treatment.

Conclusion

From the above clarifications, it can be concluded that Panchavalkala cream efficiently decreases the microbial load, clinically controls infection, hastens wound debridement and can be recommended in the management of chronic non healing wounds.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kerstein MD. Wound infection: Assessment and management. Wounds. 1996;8:141–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madsen SM, Westh H, Danielsen L, Rosdahl VT. Bacterial colonization and healing of venous leg ulcers. APMIS. 1996;104:895–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1996.tb04955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutting KF, Harding KG. Criteria for identifying wound infection. J Wound Care. 1994;3:198–201. doi: 10.12968/jowc.1994.3.4.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hultén L. Dressings for surgical wounds. Am J Surg. 1994;167:42S–44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Doebbeling BN. The validity of the clinical signs and symptoms used to identify localized chronic wound infection. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9:178–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krizek T, Robson M, Kho E. Bacterial growth in skin graft survival. Surg Forum. 1967;18:518. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson MC, Lea CE, Dalton JB, Heggers JP. Quantitative bacteriology and delayed wound closure. Surg Forum. 1968;19:501–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sushruta, Sushruta Samhita, Sutra Sthana. Mishrakamadhyayam 37/22. In: Acharya VJ, editor. reprint ed. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 2009. p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV. Chronic ulcer of the leg: Clinical history. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294:1389–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6584.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar PK, Ballantyne S. Management of leg ulcers. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:674–82. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.901.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biswas TK, Mukherjee B. Plant medicines of Indian origin for wound healing activity: A review. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2003;2:25–39. doi: 10.1177/1534734603002001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao CM, George KM, Bairy KL, Somayaji SN. An apprantial of the healing profiles of oral and external (gel) metronidazole on partial thickness burn wounds. Indian J Pharmacol. 2000;32:282–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shri Bhavamishra, Bhavprakasha, Poorva Khanda. Mishraprakaranam, 6/202. In: Mishra SB, Vaishya SR, editors. 8th ed. I. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Bhawan; 2012. p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibidem. Bhavprakasha, Mishraprakaranam, 192. :187. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vagbhata, Ashtanga Hridaya, Sutrasthana . Rasabhedeeya Adhyaya, 10/21. In: Vaidya BH, editor. 9th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Orientalia Publication; 2002. p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asolkar LV, Kakar KK, Chakraborty OJ. New Delhi: Publications and Information Directorate, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research; 1965. A Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants with Active Principal. Part-I; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villegas LF, Fernandez ID, Maldonado H, Torres R, Zavaleta A, Vaisberg AJ, Hammond GB. Evaluation of the wound-healing activity of selected traditional medicinal plants from Peru. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;55:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sukhlal MD. In vitro antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of some Ficus species. Pharmacogn Mag. 2008;4:124–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patil VV, Pimpikar VR. Pharmacognostical studies and evaluation of anti inflammatory activity of Ficus bengalensis linn. J Young Pharm. 2009;1:110–1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preeti R, Devanathan VV, Loganathan M. Antimicrobial and antioxidant efficacy of some medicinal plants against food born pathogens. Adv Biol Res. 2010;4:122–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mousa O, Vuorela P, Kiviranta J, Wahab SA, Hiltunen R, Vuorela H. Bioactivity of certain Egyptian Ficus species. J Ethnopharmacol. 1994;41:71–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakare NV, Suralkar AA. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Thespesia populnea bark extract. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikesh LS, Geeta W, Bechan S. Antioxidant activities and phenolic contents of the aqueous extracts of some Indian medicinal plants. J Med Plants Res. 2009;3:944–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hameed I, Dastagir G, Hussain F. Nutritional and elemental analyses of some selected medicinal plants of the Ficus species. Pak J Bot. 2008;40:2493–502. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiran KY, Mir KA. Element content analysis of plants of genus Ficus using atomic absorption spectrometer. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;5:317–21. [Google Scholar]