Abstract

Circularization was recently recognized to broadly expand transcriptome complexity. Here, we exploit massive Drosophila total RNA-sequencing data, >5 billion paired-end reads from >100 libraries covering diverse developmental stages, tissues and cultured cells, to rigorously annotate >2500 fruitfly circular RNAs. These mostly derive from back-splicing of protein-coding genes and lack poly(A) tails, and circularization of hundreds of genes is conserved across multiple Drosophila species. We elucidate structural and sequence properties of Drosophila circular RNAs, which exhibit commonalities and distinctions from mammalian circles. Notably, Drosophila circular RNAs harbor >1000 well-conserved canonical miRNA seed matches, especially within coding regions, and coding conserved miRNA sites reside preferentially within circularized exons. Finally, we analyze the developmental and tissue specificity of circular RNAs, and note their preferred derivation from neural genes and enhanced accumulation in neural tissues. Interestingly, circular isoforms increase dramatically relative to linear isoforms during CNS aging, and constitute a novel aging biomarker.

Introduction

While bulk cellular RNAs are generally believed to be linear, RNA can also exist in circular form. Scattered examples were described decades ago, including plant viroids (Sanger et al., 1976) and products of Tetrahymena ribosomal RNA (rRNA) loci (Grabowski et al., 1981), murine SRY (Capel et al., 1993), human ets-1 (Cocquerelle et al., 1993) and DCC (Nigro et al., 1991) genes. Other circles have emerged across a broad range of species, especially as empowered by advances in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technology (Jeck and Sharpless, 2014).

Circular species are depleted from typical dT-primed libraries aimed at enriching mRNA, but are captured in total RNA-seq libraries depleted of rRNA. In particular, circular RNAs can be inferred via split reads that map out-of-order with respect to the genome. As out-of-order mappings might be explained by other processes, such as exon-shuffling (Al-Balool et al., 2011), additional evidence is needed to support the interpretation of nonlinearity. For example, circular RNAs are resistant to RNase R, which preferentially degrades linear species (Jeck and Sharpless, 2014). Altogether, recent studies reveal a plethora of RNA circles in bacterial and metazoan species (Danan et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2014; Memczak et al., 2013; Salzman et al., 2013; Salzman et al., 2012).

Most circular RNAs arise from ”back-splicing”, where a 5′ splice donor joins an upstream 3′ splice acceptor (Jeck and Sharpless, 2014). The specificity of this process is not well understood, but introns that flank mammalian circular RNAs are longer than average (Salzman et al., 2012) and are enriched for flanking repeat elements (Jeck et al., 2013). However, the abundance of circular RNAs can vary between tissues, and does not necessarily correlate with host mRNAs (Salzman et al., 2013). This might reflect different decay rates of circular and linear isoforms, but may hint at regulation of the circularization process.

Little is known of circular RNA biology. Select circles act as microRNA (miRNA) sponges that titrate miRNA/Argonaute (Ago) complexes. The clearest case is the circular RNA cIRS7 from the vertebrate CDR1 antisense transcript (CDR1as). It contains ~70 conserved target sites for miR-7, is bound by Ago proteins and competes for miR-7 targeting (Hansen et al., 2013; Memczak et al., 2013). For the most part, though, possible functions of the vast majority of circular RNAs remain unclear, since they seem infrequently to contain conserved miRNA target sites (Memczak et al., 2013). It might be that circular RNAs are a spurious, but tolerated, aspect of the transcriptome (Guo et al., 2014).

In this study, we mined 10 billion total RNA-seq reads (5 billion paired-end reads) from >100 libraries covering diverse Drosophila tissues and cell lines to annotate >2500 circular RNAs with high confidence. This enabled comprehensive analyses regarding their sequence and structural properties. Notably, strongly lengthened flanking introns are a major determinant that correlates with circular RNA accumulation. In terms of biology, our analyses provided reiterative focus of circular RNAs to the nervous system and especially the aging CNS. We also find evidence for thousands of conserved miRNA binding sites within circles, and that coding miRNA sites preferentially reside within circularizing regions. Altogether, we provide a knowledge base for studies of circular RNA biogenesis and function in this model system.

Results

Annotation of circular RNAs from Drosophila tissue and cell line total RNA-seq data

We recently annotated the Drosophila melanogaster transcriptome using stranded, poly(A)+ RNA data from diverse developmental stages, tissues and cell lines (Brown et al., 2014b). However, as various transcript intermediates and some mature transcripts are not polyadenylated, we generated companion stranded, paired-end, rRNA-depleted, total RNA-seq data (B.R.G. and S.E.C., in preparation). Here, we mined >5 billion read pairs from 103 total RNA libraries (Table S1) for circular RNAs. In principle, these might be inferred via read pairs that map out-of-order with respect to the linear genome. In practice, we found substantial uncertainties when simply analyzing out-of-order read pairs. This might be due, in part, to chimeric transcripts generated during library preparation (McManus et al., 2010). We therefore focused on individual uniquely-mapped reads exhibiting split mappings to out-of-order positions (Figure 1A). Our initial survey yielded >3 million such candidates.

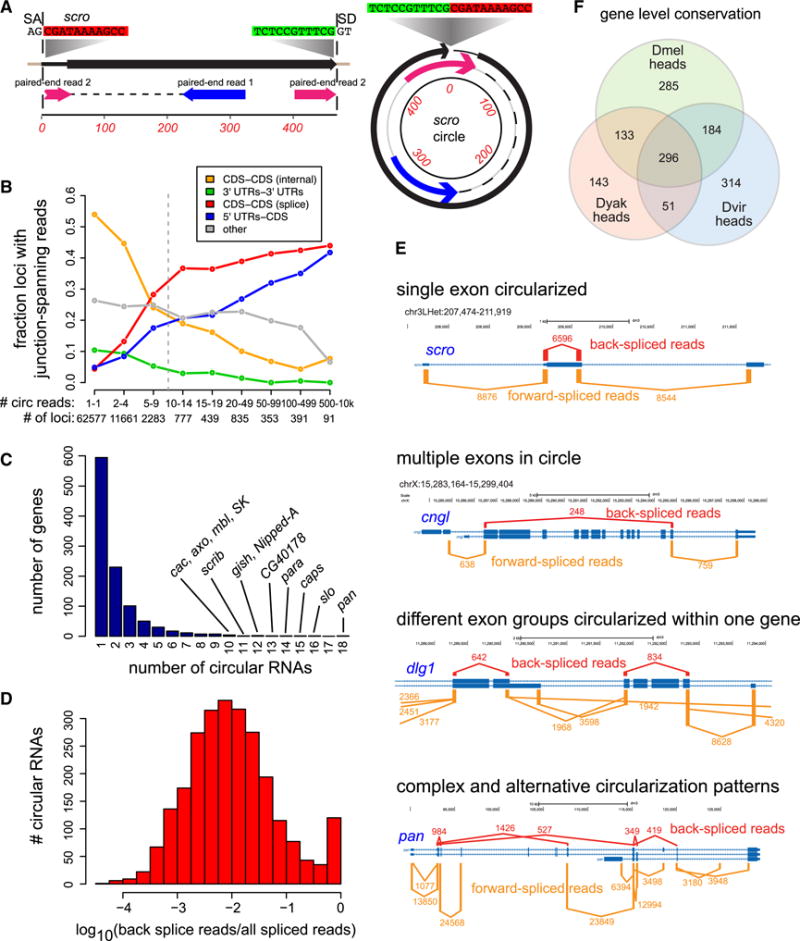

Figure 1. Annotation and examples of Drosophila circular RNAs.

(A) Example of a circularizing exon from scro. A paired-end read maps with an out-of-order junction spanning a splice junction (left gene model), consistent with derivation from a back-splicing event that generates a circular RNA (right gene model). (B) Analysis of all loci to which reads were mapped to putative out-of-order genomic junctions. These exhibit progressive enrichment of annotated CDS-CDS and 5′UTR-CDS splice sites amongst higher expressed loci. (C) Distribution of circular RNAs amongst genes. (D) Fraction of back-spliced relative to all spliced reads amongst well-accumulated circles (≥10 back-spliced reads). For reference, log10(−1) is 10% of reads, and log10(−2) is 1%. (E) Examples that illustrate the diversity in configurations of circularizing exons. The red bars above and orange bars below the gene models denote the number of back-spliced and forward-spliced reads at each junction, respectively, and are drawn to scale. Not shown are other alternative forward-spliced junctions, including skipped exons, or lower-expressed back-spliced junctions. (F) Gene-based assessment of the conservation for 1:1:1 D. melanogaster/D. yakuba/D. virilis orthologs to generate circular RNAs, based on analysis of head total RNA-seq data. All two-way species overlaps were significant by chi-squared test to p<2.2E-16, as was the three-way overlap. See also Figures S1–S2.

Known circular RNAs are typically flanked by GT/AG splice sites reflecting back-splicing (Jeck and Sharpless, 2014). We observed progressive increases in flanking GT/AG in bins of increasing circular RNA levels (Figure S1). While 3% of junctions with 1–10 reads were flanked by GT/AG (7x over background), ~80% of junctions with >1000 reads had flanking GT/AG (~200x enrichment). Of the highest expressed junctions not flanked by GT/AG, most overlapped rRNA or repeats. As sequence errors within repetitive sequences might generate fortuitous “unique” mappings, we focused subsequent analyses on ~80,000 junction events flanked by GT/AG.

Most of these were recovered just once, and only a minority were located at known splice sites. Notably, a large fraction of lower-expressed (1–9 reads) out-of-order junctions overlapped with mRNAs, but did not align with annotated splice sites (Figure 1B, orange line, “internal CDS”). In contrast, the fraction of loci matching known splice junctions increased progressively across bins of higher-expressed out-of-order junctions (Figure 1B, red and blue lines). Inspection of “internal CDS” loci often showed heterogeneous patterns with multiple out-of-order read junctions, instead of specific out-of-order junction reads characteristic of higher-expressed loci. As these appeared to represent artifacts, we filtered out ~40,000 such “internal CDS” loci. A minority of these accounted for a substantial number of reads: only ~350 had 10 or more out-of-order reads mapped to them, and the top 5 loci produced 3075 out-of-order junctions (Figure S2A). We also noted some specific, well-supported, out-of-order loci flanked by GT/AG, which did not overlap splice junctions (Figure S2B).

The 38,115 remaining loci generated at least one out-of-order read that precisely spanned an annotated splice site. We set a cutoff of 10 reads for subsequent analyses of confidently circularized exons, yielding 2513 loci. Most genes generated one or two circles, but some genes yielded multiple distinct circularized products (Figure 1C). We provide the coordinates, associated genes, and levels of circular RNAs in Table S2, including higher (≥10) and lower (<10) confidence loci.

General features of circularizing loci

Consistency of mate-pair read locations

If back-spliced reads genuinely derive from circular species, we expect their mate pairs to be located within the bounds of the circular RNA. Amongst 18 head datasets, we identified >120,000 back-spliced reads. Of these, only 0.468% of mate pairs mapped outside of circles. Half of these were accounted by 9 loci, most of whose mates mapped to the same transcript but outside the circle boundary, mapped to the antisense strand, or mapped to a neighboring gene model. These rare events may potentially derive from scrambled exons, genomic rearrangements, or molecular biology artifacts. Of the remainder, 8.70% of mate pairs were unmapped, while 90.8% of mate pairs mapped within the inferred circle limits. Thus, the vast majority of back-spliced reads are consistent with derivation from circular species.

Depletion of circular reads amongst poly(A)+ transcripts

Circular RNAs are expected to lack poly(A) tails, which are normally required for stable accumulation of mRNA. We examined this using several 2×100nt mRNA-seq libraries from 1 day heads, generated from the same RNA samples as corresponding total RNA-seq libraries (Table S1). The total RNA and poly(A) data contained similar numbers of raw read pairs (263 and 250 million, respectively) and similar numbers of forward-spliced reads across circularizing junctions (2,483,732 and 2,222,897, respectively). In contrast, we identified 33,706 back-spliced reads in the total RNA data but only 276 in the poly(A)+ data; the data are tabulated per locus in Table S3. The >100 fold depletion of back-spliced reads in mRNA-seq data indicates the inferred circles indeed lack poly(A) tails.

Abundance of circular transcripts relative to linear counterparts

Loci might meet the 10 back-splice read cutoff by virtue of rare processing of highly-expressed transcripts, or via splicing events with a more palpable “choice” between forward- and back-splicing. If their role was in trans, it might not matter which strategy generated a set level of circular RNA. In this regard, the highest-expressed circles were from mbl and Dbp80, which generated >20,000 and >10,000 back-spliced reads of specific junctions (Table S2). On the other hand, circularization might have roles in cis; i.e., back-splicing should oppose protein-coding potential. In this scenario, it would be relevant to know if back-spliced reads comprise a substantial fraction of forward-spliced reads recovered at circularizing junctions.

We observed a range of apparent back-splicing efficiencies. Across the aggregate data, >1000 circles accumulated back-spliced reads at >1% of forward-spliced reads, with 274 circles where back-splicing accounted for >10% of splice events, and 123 circles that were the majority of splice events (Figure 1D and Table S3). As discussed later, there is tissue-specific accumulation of back-spliced reads. Notably, circular species are substantially higher in heads, where 300 genes have higher levels of back-spliced reads than forward-spliced reads. Thus, back-splicing is abundant at hundreds of loci, especially in particular settings.

Diversity of circularization patterns

We illustrate structural complexities amongst well-expressed circular RNAs. The first example shows a typical high-efficiency singleexon circularization event at scro (Figure 1E). Most circles contain one or a few exons; however, a circular RNA from cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel-like (cngl) is supported by abundant back-spliced reads that specifically traverse 13 exons (Figure 1E). A subset of genes generated multiple circular RNAs. For example, the guanylate kinase discs large 1 (dlg1) is not only alternatively spliced, it also yields two multi-exon circular RNAs (Figure 1E). Finally, we highlight the Wnt pathway transcription factor pangolin for its complex circularization patterns. Of 18 circular products from this gene, the top 5 are depicted in Figure 1E. We observe alternative and interleaved events, where the same splice sites can participate in multiple forward and backward splicing reactions, either to adjacent exons or to distant skipped exons.

Experimental validation of circular RNAs

We validated circular RNAs using several strategies. Our first assays utilized Northern blotting. Although Northerns are not very sensitive, they have the distinct advantage of distinguishing transcripts bearing similar sequences. We confirmed longer full-length and shorter circular transcripts for muscleblind (mbl), the sole fly circular RNA from the “pre-RNA-seq” literature (Houseley et al., 2006), as well as for plexA, dlg1, and scro (Figure 2A). Tests of two tissues detected two circles (mbl and plexA) in ovaries, whereas all four were detected in heads. Unlike their mRNA counterparts, circular RNAs were depleted following poly(A) selection (Figure 2A). To provide evidence of their nonlinearity, we treated samples with exonuclease RNase R. This reduced levels of mRNAs but not of circular species (Figure 2B).

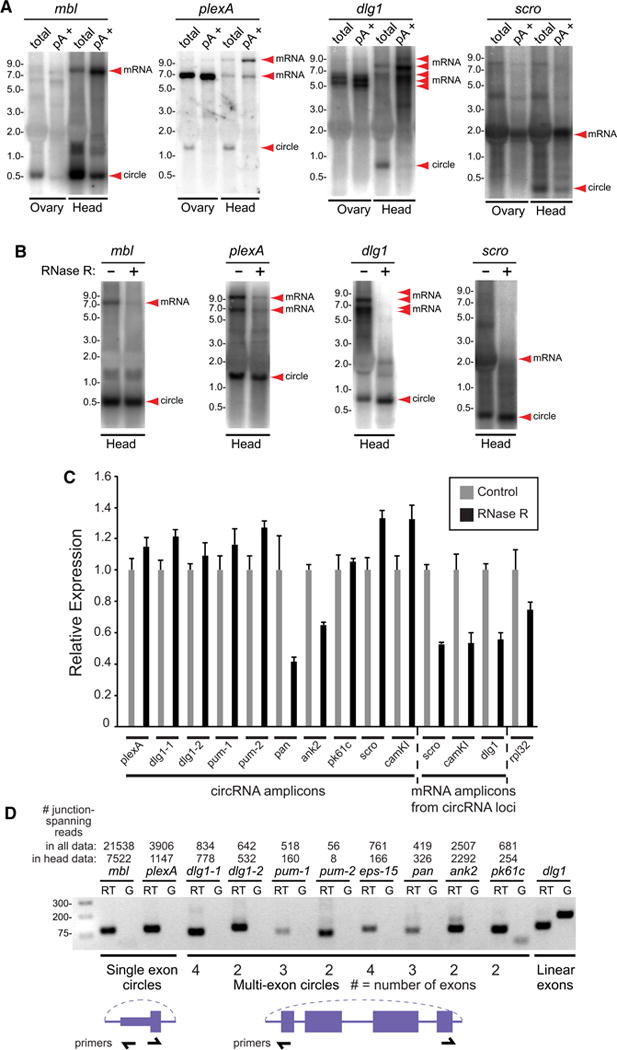

Figure 2. Experimental validation of circular RNAs.

(A) Northern blots of total and polyadenylated (pA+) RNAs from ovary and head. Linear mRNAs are enriched in pA+ samples while circular species are depleted. (B) Northern analysis comparing total and exoribonuclease RNase R-treated RNAs from heads. Linear mRNA forms are depleted by RNase R while circular species are resistant. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNase R-treated samples. Signals were normalized to those obtained using controls samples that were not treated with RNase R. Most of the circular RNA amplicons were maintained or even increased following RNase R treatment. (D) End-point RT-PCR verifies back-splicing of single-exon and multi-exon circles. Genomic DNA (G) was used a negative control template for these reactions. These tests validate circularization of pan and ank2, which appeared to be sensitive in the RNase R tests.

We next performed qPCR tests of control and RNase R-treated samples using inward-facing primer sets (that amplify mRNA species) and outward-facing primer sets (that amplify circular species). In practice, we found it difficult to achieve a high degree of discrimination, possibly since qPCR can amplify partially degraded transcripts. Nevertheless, we generally confirmed that under conditions where linear mRNAs from heads were substantially decreased by RNase R, most circular RNA amplicons were not affected, or even increased slightly (Figure 2C).

We also used a non-quantitative assay to detect circular RNAs using end-point RT-PCR. We confirmed specific products for all cases tested (Figure 2D), including pangolin and ank2, both of which had appeared sensitive to RNase R. Finally, we sequenced circular junctions from cloned rt-PCR products, two from pangolin and two from dlg1. All were formed precisely by back-splicing across junctions inferred from total RNA-seq data (not shown). Altogether, these tests validate that our computational pipeline identified circular RNAs accurately.

Conservation of circular RNAs amongst Drosophila species

We assessed the conservation of circularization across Drosophila. We sequenced total RNA from heads of D. yakuba, a close relative to D. melanogaster (<10 million years apart, MYA) and from D. virilis, which is very divergent (40–60 MYA). The application of our circle detection pipeline in D. melanogaster in the other species was complicated by shorter read length (75 vs 100 nt paired end data). To facilitate comparisons, we supplemented the output of our circular RNA annotation pipeline by directly mapping reads across potential back-splices using slightly relaxed parameters, requiring 15 instead of 20 nt mapping (see Methods). We confirmed this procedure still specifically identified species of interest, since only 1–2% of matepairs to back-spliced reads mapped outside of inferred circles. Annotations of circular RNAs in D. yakuba and D. virilis are found in Table S2.

Since many genes produced multiple circles in D. melanogaster, and sampling was lower in the other species, we performed a conservative gene-level comparison using only D. mel head circles. Using only genes with 3-way orthologs across this phylogeny, we categorized the distribution of loci that generated multiple (two or more) back-spliced reads in each respective species. While there are candidately a number of species-specific back-splicing events, the propensity of Drosophila genes to generate circular RNAs is broadly conserved, with nearly 300 genes that were subject to back-splicing in all three species (Figure 1F).

As the breadth and depth of datasets in D. melanogaster is far greater than in these species, we expect the degree of overlaps detected to be a minimum estimate. Nevertheless, these data are consistent with the notion that particular features and/or functions of circularization are under substantial evolutionary constraint.

Structural properties of circular RNAs

While back-splicing events encompass diverse patterns (Figure 1), we sought characteristic features enriched amongst well-expressed circles. To do so, we stratified circular RNAs by level, to highlight if any given feature correlated with increasing circular RNA accumulation. We normalized circle expression as the number of junction spanning reads per million raw reads per host gene RPKM, and divided these into five bins: 0–0.0001 (263 circles), 0.0001–0.0005 (632 circles), 0.0005–0.001 (301 circles), 0.001 to 0.005 (445 circles) and >0.005 (160 circles).

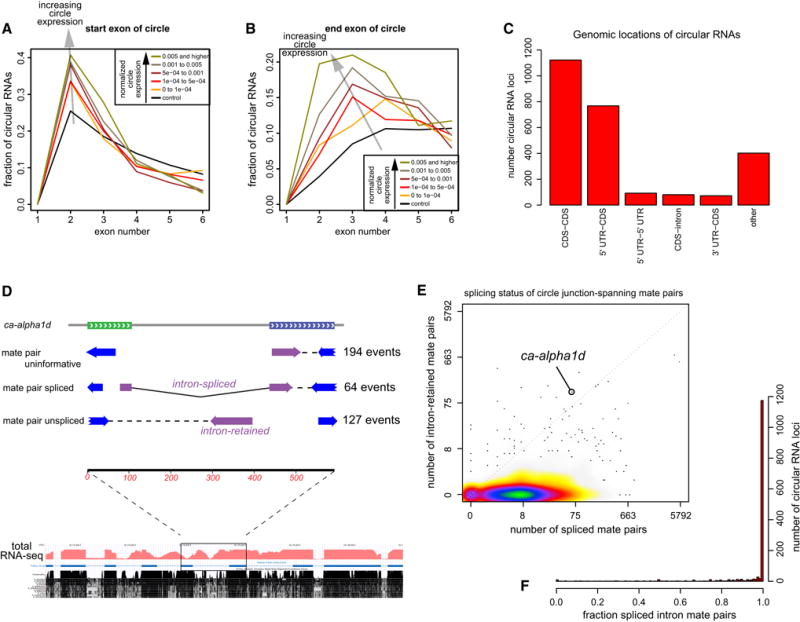

5′ positional bias of circularizing exons

We observed circularization was biased to involve second exons of protein-coding genes (Figure 3A). Although random sampling of circularizing exons amongst aggregate multi-exon gene models yields an excess of second exon events, there was significantly elevated bias of second exon involvement amongst genuine circular RNAs (0–0.0001 bin, p=8.1E-02, 0.0001–0.0005 and 0.0005–0.001, both p<5.3E-04, 0.001 to 0.005 and 0.005 and higher, both p<1.2E-09). The location of the last exon in the circular RNA was also biased towards the 5′ end compared to the control set (all bins: p<1E-10). These trends were significantly enhanced across each pairwise comparison of progressively increasing bin of higher-expressed circular RNAs (p=2.1E-01, 5.0E-02, 6.7E-03, 2.2E-03, respectively, Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Circular RNAs exhibit characteristic exonic positions and are internally spliced.

(A, B) Analysis of exon positions. To identify functional correlations, we binned circular RNAs according to levels of back-spliced reads. Properties of background circles generated from random exons are shown in black. (A) Start exon of circular RNAs. Background circles exhibit bias to initiate with second exons (e.g., for genes with 3 exons, the only possibility is to circularize exon 2). However, circular RNAs exhibit enhanced involvement of second exons. (B) End exon of circular RNAs. Circular RNAs are most enriched for exons involving positions 2–4 of gene models, and the bias towards the 5′ end increases progressively with higher levels of junction-spanning reads. (C) Genomic annotations of circular RNAs. The dominant classes involve 5′-UTR-CDS exons and CDS-only exons. (D) Assessment of internal splicing of multi-exon circles. Shown is an example from ca-alpha1d, for which some mate-pairs of back-spliced reads are spliced and some derive from the intron. Total RNA-seq data below shows that intronic reads accumulate broadly across neighboring introns not involved in the circle. (E) Genomewide analysis shows that the vast majority of RNA circles from individual genomic loci are mostly spliced. (F) Barplot summary showing that aggregate circular RNAs are predominantly internally spliced.

Generally efficient splicing of internal introns within circles

Circularizing events typically encompassed 1–4 exons and mostly comprised 5′ UTR-CDS and CDS-CDS junctions (Figure 3C). Given that a substantial fraction of circular RNAs are multi-exonic, a question arises if they are internally spliced. Figure 3D illustrates Ca2+-channel α1 subunit D (ca-alpha1d), for which we recovered ~400 reads that consistently circularize exons 7 and 8. Amongst informative mate-pairs of back-spliced reads (i.e., reads that do not simply contain continuous exonic sequence) 64 were spliced while 127 contained intronic sequence (Figure 3D). Thus, splicing is well-suppressed within this circle.

We examined this issue comprehensively. The paired-end data contained 1590 circles for which mate pair reads were informative with respect to splicing status. We tabulated the number of spliced and intron-retained mate pairs for each of these circles, and observed that 90% of loci exhibited >90% of spliced mate pair reads. We summarized these data in Figure 3E, which emphasizes that intron-retaining circles such as ca-alpha1d are extremely rare. The bias towards splicing of internal exons was even more extreme when summing all informative mate pairs (Figure 3F). Inspection of total RNA-seq data at ca-alpha1d showed abundant intronic reads not only within the circularizing region, but also from upstream and downstream introns (Figure 3D). Thus, intron retention at ca-alpha1d is not a specific attribute of the circle. Otherwise, multi-exon circles in Drosophila are nearly always spliced.

Apparent lack of flanking nucleotide motifs or intronic pairing

Human circular RNAs are enriched for flanking Alu repeat elements, especially in complementary orientation (Jeck et al., 2013). To investigate involvement of specific sequence motifs in biogenesis of circular RNAs, we performed de-novo motif finding in circularizing flanks. We first analyzed regions flanking (<500nt windows) the 485 “high stringency” circular RNAs from (Jeck et al., 2013), and confirmed we could identify motifs associated with ALU repeats, as described (Figure S3A). In contrast, similar analysis of circular RNA loci in D. melanogaster (which lacks ALU repeats) yielded only canonical splice-donor and splice-acceptor motifs, along with some simple repeats (Figure S3B). However, we recovered precisely the same motifs at similar frequencies and expectancies in intronic sequences flanking random control exon pairs. We also studied nucleotide composition and sequence conservation between circles and controls, but this did not reveal any differences (Figure S4A and data not shown).

We also performed many analyses for potential enrichment of secondary structures formed between various windows of flanking intronic sequences, also by stratifying these by G:C content. These tests showed modest overall tendencies for increased duplexing between introns flanking circular RNAs compared to control exons, especially within smaller size flanking windows (20 and 50nt) and in mid-ranges of G:C content (Figure S4B–E). However, when we stratified the data by circle levels, we did not observe correlations between increased pairing with circle accumulation (see also Supplementary Text), suggesting this is not a primary determinant of the process. We also note a modest tendency for statistically less pairing within the local regions on the distant exonic regions that are brought together by circularization, compared to control exon pairs (Figure S4F). However, overall, it appears that Drosophila RNA circularization does not appear to be driven by flanking sequence or structural complementarity, as in mammals.

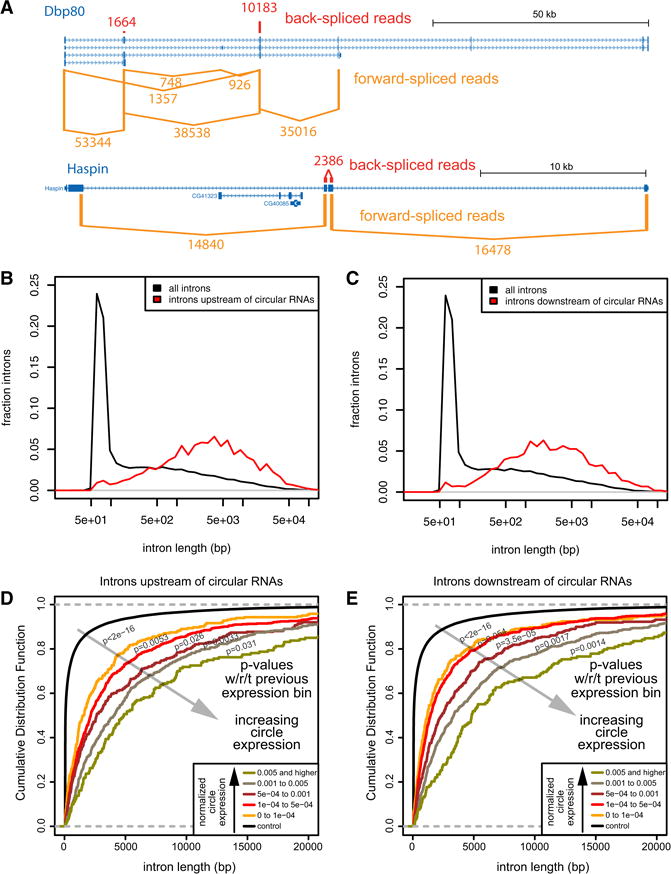

Strong bias for long flanking introns

Some of the most abundant circular RNAs are derived from exons with long flanking introns. For example, the dead box helicase/kinase Dbp80 generates two abundant circles from 5′-biased exons, each of which is flanked by 10–30 kb introns, while the kinase Haspin generates an abundant two-exon circle with a small internal intron and flanking >15kb introns (Figure 4A). We therefore examined flanking intron lengths more systematically. D. melanogaster intron lengths are bimodal (Lim and Burge, 2001), with a predominant peak of 50–150 bp followed by a broad distribution of longer introns.

Figure 4. Long flanking introns are a major determinant for RNA circularization.

(A) Examples of well-expressed circular RNAs that are flanked by long upstream and downstream introns. (B) Comparison of upstream intron length. Drosophila introns exhibit a bimodal distribution of short lengths and a broad tail of longer lengths. Circular RNAs are biased to be flanked by longer upstream introns than the typical “long” intron class. (C) Circular RNAs are also biased to be flanked by long downstream introns. (D, E) The correlation of flanking intron length was examined across five different different cutoffs of junction-spanning reads. For both upstream (D) and downstream (E) flanking introns, circular RNAs supported by progressively higher numbers of junction-spanning reads were biased for progressively longer flanking intron lengths. Wilcoxons rank-sum tests showed that the increase in overall flanking intron length was significantly greater for each successive bin of increasing circular RNA expression examined. See also Figures S3–S5.

We observed that circularized exons were flanked by significantly longer introns than average, both upstream and downstream (Figure 4B,C). Total Drosophila introns have a median length of 96 bp, and the median length of all >200 bp introns was 1099 bp. By contrast, the introns upstream and downstream of circular RNAs had median lengths of 4662 and 2962 bp, respectively. Thus, introns flanking circularizing exons are much longer than expected, even when excluding the dominant class of short introns. The functional correlation of flanking intron length and circular RNA abundance was evident upon binning circular RNA levels. We observe independently for upstream and downstream introns that progressively higher-expressed RNA circles were associated with progressively longer average flanking intron lengths (Figure 4D,E). Statistical analysis showed that not only were flanking intron lengths significantly different from background introns (<2E-16 in all cases), for each of five progressively increasing bins of circular RNA expression, the average length distributions of both flanking upstream and downstream introns became significantly larger (Figure 4D,E).

Since first introns in Drosophila are often longer than other introns, the properties of long flanking introns and 5′ exon bias (Figure 3A) are potentially linked. However, some prime examples of circular species with long flanking introns did not involve second exons (Figure 4A). To test if we dissociate these features, we performed the analyses above using 684 circles that were not adjacent to first introns. We still observed progressive increases in flanking intron lengths with higher circular RNA accumulation (Figure S5), for both upstream and downstream introns. Although increased flanking intron length was observed in mammalian circular RNAs (Salzman et al., 2013), these data suggest that long flanking introns are an intrinsic determinant for circularization in Drosophila.

Relevance of Drosophila circular RNAs to miRNA regulation

We assessed the extent to which miRNA sites reside on Drosophila circular RNAs, which predominantly involve 5′ UTRs and coding regions (Figure 3C). A relevant fact is that Drosophila coding regions exhibit much greater utilization of conserved miRNA target sites than mammals (Schnall-Levin et al., 2010). We typically consider miRNAs that are conserved throughout Sophophora to be well-conserved, and catalogued 2–8 or 6merA seed matches to such miRNAs (Ruby et al., 2007). We also implemented a stricter criterion for coding sites, in order to surpass simple coding constraints, by requiring putative sites of pan-Drosophilid miRNAs to be present in 11/12 genomes. As well, since miRNA* (star) strands frequently have conserved regulatory activity (Okamura et al., 2008), we similarly catalogued matches to conserved miRNA* strands (Table S4). However, so as not to inflate site numbers, we kept their tallies separate, and also filtered their matches for low-complexity motifs.

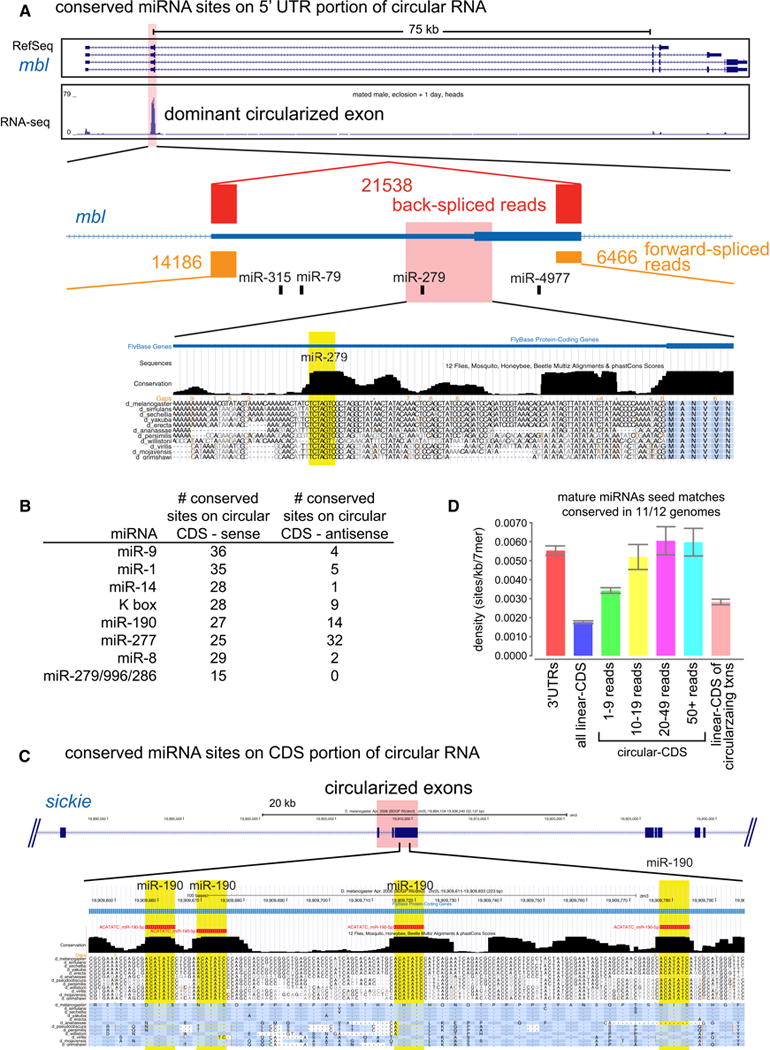

These analyses indicate that Drosophila circular RNAs bear a substantial population of constrained miRNA sites. From the most conservative view, there are ~150 deeply conserved 2–8 seed sites for pan-Drosophilid mature miRNAs strictly within UTRs. This rises to >800 for Sophophoran-conserved mature or star miRNAs of both target site definitions, again considering only UTRs. While miRNA sites are generally considered to reside in 3′ UTRs, as circular RNAs frequently involve 5′ UTRs, there are more conserved miRNA binding sites in circularized 5′ UTRs than 3′ UTRs (Table S4). Thus, circular RNAs may explain the atypical location of some conserved miRNA sites. For example, the highest-expressed circular RNA derives from a 5′ UTR/coding exon of muscleblind (mbl). The mbl circle is preferentially expressed in the nervous system (Figure 2A), and contains highly conserved 5′ UTR sites for several miRNAs, including neural miR-279 and miR-315 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. miRNA binding sites within circular RNAs.

(A) A highly expressed circle from muscleblind (mbl), which involves its 5′ UTR and first coding exon and is flanked by long introns. Far greater numbers of back-spliced reads were recovered than for forward-spliced reads. The mbl 5′ UTR includes well-conserved binding sites for several neural miRNAs, including for the miR-279 seed family. (B) Summary of the top pan-Drosophilid-conserved miRNA binding sites located with coding regions of circular RNAs. In general, these are dominantly found on the sense strands of these genes. (C) Example of a coding circular RNA from sickie, which contains a remarkable density of deeply-conserved miR-190 binding sites. It is evident that each miR-190 site has been selectively constrained for primary sequence, relative to the neighboring coding regions. (D) Comparison of density of well-conserved 2–8 seed matches for well-conserved miRNAs in circularizing versus linear coding regions. Circularizing coding regions are subject to much higher miRNA targeting than bulk linear coding transcriptome. This holds true when restricting the comparison directly to linear coding regions of transcripts that undergo circularization. Comparison of different bins of circular RNA accumulation shows that the lowest expression bin has a lower site density compared to the higher bins, which exhibit similar density to 3′ UTRs.

The numbers of putative miRNA binding sites on circular RNAs increase dramatically when considering coding regions. Even in the most cautious interpretation, focusing only on the most deeply-conserved 2–8 seed matches of pan-Drosophilid mature miRNAs, there are still ~1000 such sites (Table S4). Many-fold higher numbers of coding sites were recorded with slightly less stringent parameters. To control for the possibility that coding regions might intrinsically encode amino acids that preferentially overlap miRNA seeds, we compared the numbers of deeply conserved seed matches on the antisense strands of circular RNA coding regions. The miRNAs with the highest number of strictly-conserved coding region seed matches had far fewer matches to the antisense strands of these circles (Figure 5B).

A striking example of a circular RNA bearing coding miRNA sites derives from sickie, a calponin homology domain/ATPase (Figure 5C). Although its circles were modestly sequenced (24 total reads), they contain four deeply-conserved 2–8 seed matches for miR-190 within ~120 bp. There are few Drosophila 3′ UTRs with this many conserved seed matches for an individual miRNA (Ruby et al., 2007), and these are invariably located within larger regions. For example, Hs3st-A is the only Drosophila 3′ UTR bearing four well-conserved 2–8 seed matches for miR-190, but these are distributed across 1.3 kb. Although the four miR-190 sites are found within sickie coding sequence, the conservation pattern clearly shows the miRNA sites are selectively constrained. Moreover, one of the miR-190 sites resides in a different frame than the others, demonstrating primary sequence constraint independent of coding sequence.

We noticed that 7/10 top miRNAs that target circular RNAs overlap a previous analysis of top seed matches across all Drosophila coding regions (Schnall-Levin et al., 2010). We were thus curious if Drosophila coding miRNA sites might exhibit preference for residence on circular RNAs. We first compared the density of miRNA binding sites in circular versus linear coding regions, focusing on pan-Drosophilid miRNAs and the high-stringency definition for their seed matches (11/12 species). Notably, circular coding regions harbored ~3 times the density of well-conserved miRNA binding sites as did linear portions of the coding transcriptome, and were similar to 3′ UTRs (Figure 5D). As well, the lowest expressed circular RNAs (supported by fewer than 10 reads) contained about half as many miRNA sites as did various higher-expressed bins of circular RNAs.

These data suggested a preference for miRNA sites to reside on well-expressed circular RNAs. However, an alternate scenario might be that circularizing transcripts are preferentially subject to miRNA targeting, but not specifically within their circular exons. To address this, we directly compared the distribution of well-conserved miRNA sites within the circular and non-circularizing portions of transcripts that generate circular RNAs. We observed that linear coding exons of circularizing transcripts had much lower density of conserved miRNA sites than their circularizing portions (Figure 5D).

Altogether, these analyses uncover a novel facet of the previously described propensity of Drosophila coding regions to harbor miRNA sites. In particular, the fact that circularizing coding regions preferentially harbor deeply-conserved miRNA sites relative to various classes of linear coding regions implies they are so-positioned to have impact on post-transcriptional regulatory networks.

Circular RNAs are biased for neural-related genes and for neural expression

The >100 libraries analyzed permit diverse analyses of the stage-, tissue-, and cell-specificity of circular RNA expression in D. melanogaster. The levels of circular RNA junction reads in each individual library, normalized per million raw reads in each dataset, are presented in Table S5. To assess circular RNA abundance more compactly and more specifically, we depict circular junction spanning reads per million raw reads per host gene RPKM in a heatmap (Figure 6A). This rubric normalizes for the possibility that genes that generate circular RNAs might themselves exhibit regulated expression.

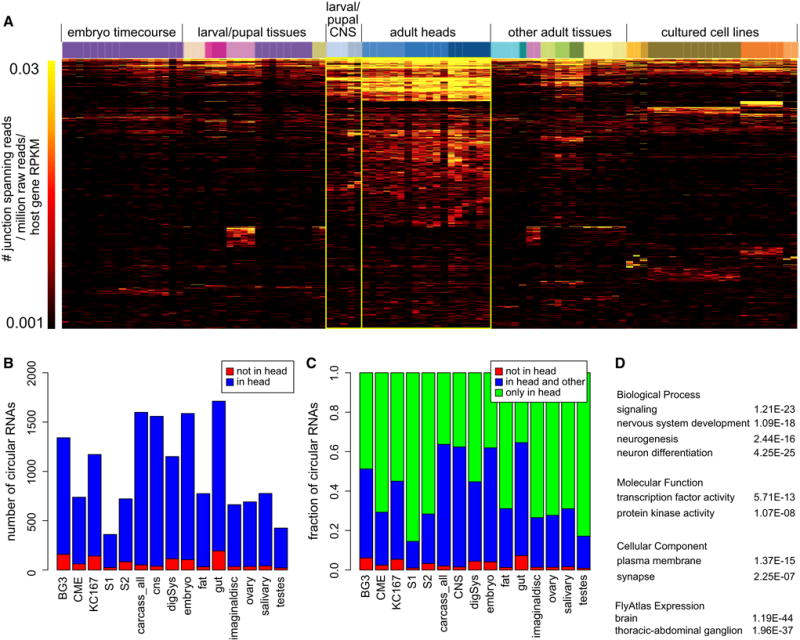

Figure 6. Neural-biased expression and relevance of circular RNAs.

(A) Heatmap of circle abundance across 103 Drosophila libraries. Each column represent a library, and each row represents a circular RNA ordered by highest abundance in an individual library. The main trends visible from this summary include a mild increase in circle accumulation across embryonic development, enhanced accumulation of circular RNAs in larval/pupal CNS relative to other dissected tissues of these stages, and predominant accumulation of circles in adult heads relative to all samples. In addition, the ordering of circular RNAs by rows highlights that few circles are well-expressed in a manner that is exclusive of adult heads. (B, C) Comparison of circular RNA expression in heads versus many individual developmental stages, tissues, or cell lines. Plots of numbers of loci (B) and frequency of loci (C) emphasize that few circular RNAs are not expressed in heads, and heads express many circles that are not detected elsewhere. (D) Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichments of circular RNAs reveal many gene sets that relate to neural development and/or neural function. See also Figure S6.

The well-segmented embryonic timecourse revealed progressive increase of circles with time (Figure 6A and 7A). While this might indicate that circularization correlates with development, it might also reflect that circularization occurs preferentially in tissues not present during earlier stages. For example, 3′ UTR lengthening increases with embryonic development, but this is due to a regulatory process that occurs in the CNS (Hilgers et al., 2011; Smibert et al., 2012). A similar phenomenon may occur with circularization, since levels of circular reads were elevated in dissected larval and pupal CNS relative to all embryonic samples, and were higher still in dissected adult heads. By comparison, other larval, pupal, adult tissues expressed far fewer circular reads than adult heads. The overall picture for cell lines was that they express levels of circular RNAs that are intermediate relative to the tissue panel, and biased to a more limited set of loci. We note many cell datasets are from BG3-c2, which derive from larval CNS, but these cells accumulated lower levels of circles than all other cell lines analyzed. In summary, the intact fly nervous system particularly accumulates circular RNAs.

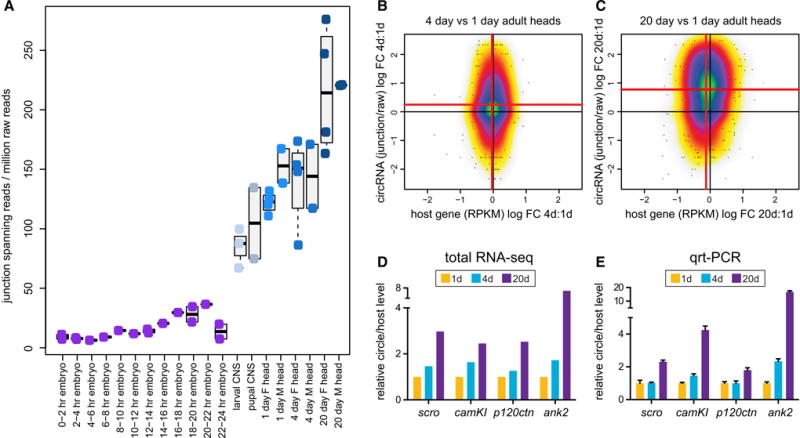

Figure 7. Age-dependent increase in circular RNAs in the nervous system.

(A) Developmental timecourse emphasizes that dissected larval/pupal CNS accumulates much higher levels of circular RNAs than does any embryonic stage. Adult heads accumulate even higher levels circular RNAs, and these increase with adult aging, as measured in independent datasets of female and male head libraries. Note the two 20 day male libraries gave nearly identical numbers. (B, C) Analysis of individual circular RNA loci demonstrates their globally increased accumulation at 4 days (B) and 20 days (C) compared to 1 day. To ensure these shifts did not represent selective increases in transcription of genes that generate RNA circles, we plotted changes in RNA circles against the changes in host gene expression. Between 1 and 4 days, the circular RNAs showed significant increase in abundance (Wilcoxon p=1.1e-4) while the host mRNA transcripts were unchanged (p=0.88). Between 1 day and 20 days the increase in circle expression was even more significant (p<2e-16), while host mRNAs showed a slight decrease (p=0.035). (D) Age-dependent changes in selected RNA circles in total RNA-seq data. (E) qPCR assays validate age-dependent increases in accumulation of circular RNAs. See also Figure S7.

The limited diversity of circular RNAs expressed specifically outside of the nervous system was apparent when we compared the circular RNAs of each tissue/stage/cell-type directly to heads. We find that 90–95% of circles that could be annotated from any Drosophila sample were also observed in heads (Figure 6B). Reciprocally, half of the circles observed in the head were not detected in other samples (Figure 6C). Notably, even the larval/pupal central nervous system expressed 40% fewer circular RNAs than did heads. The latter result indicates the mature nervous system is enriched for circular RNAs. This is highlighted by the increased numbers of loci that generate substantial numbers of back-spliced reads. Whereas 274 circular RNAs generate ≥10% back-spliced reads in the aggregate data, there are 502 such loci in pooled head data (Table S3 and Figure S6).

Gene ontology terms enriched amongst circular RNAs are enriched for neural functions, even amongst circular RNAs expressed in non-neural settings

We assessed Gene Ontology (GO) terms amongst circularizing genes. Amongst bulk loci, numerous GO terms relating to development and signaling, neurogenesis, neural morphology or function, and neural subcellular compartments (e.g. synapse) were highly enriched (Figure 6D). Genes that generated circular RNAs were also enriched for genes with neural expression as defined by FlyAtlas (Chintapalli et al., 2007), and depleted for genes expressed in testis. Finally, we found significant overlaps between circularzing genes and specific modENCODE temporal expression clusters (Roy et al., 2010). The full GO and expression comparisons are given in Table S6.

As circularization is enhanced in the CNS, it may seem trivial that GO terms associated with circular RNAs are neural-related. However, this result was not dependent on annotating neural-expressed circles. For example, GO analysis of circular RNAs annotated from 0–2 hour embryos and S2 cells, which definitively lack neurons, still generated varieties of neural-related terms (Table S6). Thus, genes that undergo circularization are enriched for functions that are manifest with respect to the nervous system, even when such genes are expressed more broadly in the animal.

Progressive accumulation of circular RNAs in the adult central nervous system

Our datasets include several that span adult timepoints, providing an opportunity to analyze whether circular RNAs vary with age. Given that circular RNAs accumulated most prominently in heads, we focused on 1, 4 and 20 days post-eclosion, for which data were collected independently for virgin and mated females, and mated males.

Intriguingly, overall levels of circular reads per million raw library reads increased mildly from 1 to 4 days (due to variation in 1 day male data), but were elevated substantially in both sexes at 20 days (Figure 7A). Plotting junction-spanning reads per million raw library reads highlighted that aged heads accumulated, by far, the highest levels of circular RNAs of any tissue (Figure 7A). We analyzed this further by comparing levels of individual circles as a function of host mRNA levels. In the 1:4 day comparison, we observed a clear directional shift indicating a specific increase in circular RNAs relative to linear isoforms of the same transcripts (Figure 7B). This trend was much more pronounced when comparing 1:20 day samples (Figure 7C), and these trends were also seen when separating the data by sex (Figure S7).

Assessing differential expression of circular RNAs with limited numbers of junction-spanning reads was challenging, but we nonetheless identified 262 circular RNAs with significantly higher expression in 20 day versus 1 day heads (p<0.05, fold change >2, see Table S5). These genes are enriched for functional annotations related to (neural) signaling: synaptic transmission (p=2.3e-6), synapse part (2.2e-5), kinase activity (4.8e-5), as well as development: developmental process (2.9e-5).

We validated these trends for several circular RNAs. For example, scro, camKI, p120ctn, and ank2 were elevated in aged heads in the total RNA-seq data (Figure 7D), and these were similarly increased in qRT-PCR tests using independently aged head RNA samples (Figure 7E). It remains to be seen whether progressive circle accumulation has impact on brain function, but at the very least, these data indicate that circular RNAs are a novel aging biomarker in the CNS.

Discussion

Deep annotation of circular RNAs in Drosophila melanogaster

Like other classes of atypical transcripts (e.g., miRNAs), individual cases of circular RNAs were recognized decades ago (Grabowski et al., 1981; Sanger et al., 1976), but received broader attention since the advent of deep sequencing. Still little is known about how circular RNAs are made and what they do, but the foundation for these questions is a thorough annotation.

Here, we conduct the deepest and broadest effort for circular RNA annotation to date, utilizing 10 billion total RNA-seq reads (5 billion paired-end reads) from 103 libraries that cover the gamut of Drosophila developmental stages, tissues, and cell lines. These data permit a more comprehensive view into RNA circularization than initially reported (Salzman et al., 2013). We used stringent criteria to identify thousands of circular RNA junctions, and observe the bulk of confident events derive from back-splicing of annotated exons. Thus, RNA circularization broadly diversifies the Drosophila transcriptome. Even with multiple “cutting-edge” re-annotations of the Drosophila genome in recent years (Berezikov et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2014b; Graveley et al., 2011; Smibert et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2014), it seems we are still some way from understanding the genic output of what is arguably one of the best-understood animal genomes.

Biogenesis of circular RNAs

Only a small fraction of all possible back-spliced events are executed, and the substantial tissue preference of this process strongly suggests regulation of circularization. We analyzed the structural features of Drosophila circular RNAs, and determined core properties that correlate well with their accumulation. These include the presence of long flanking introns and a bias for 5′ exon positions within the transcripts, but did not include any bias for flanking intronic sequence or structural complementarity. Notably, the latter features were reported to be strongly enriched around mammalian circular RNAs (Jeck et al., 2013). While this work was in revision, flanking intronic complementarity was confirmed as a major determinant for circularization in mammals (Zhang et al., 2014). However, our studies suggest that this is not a critical feature of Drosophila circularization. Instead, our studies particularly highlight extended lengths of flanking upstream and downstream introns as mechanistic determinants. Functional tests of whether manipulating intron lengths can impact back-splicing await.

While this work was in revision, another study reported that circularization in Drosophila is promoted by the RNA binding protein Mbl (Ashwal-Fluss et al., 2014). As noted, mbl was the highest-expressed circular RNA in our studies, and it will be interesting to see how well Mbl explains tissue-specific differences in circularization. Notably, we observe less circularization in ovary than in head, correlating with less mbl mRNA and circle in ovary than in head (Figure 2A). Beyond this, our studies suggest substantial possibilities for interactions between alternative splicing and circularization (e.g., Figure 1E). Moreover, the strong CNS-bias of circularization is notable in light of the fact that the nervous system is unique in its degree of exon skipping (Brown et al., 2014a; Calarco et al., 2009), which may plausibly generate circular RNAs.

Function and biological significance of circular RNAs

A general challenge is to understand the biological impact of RNA circularization. Perhaps the best-known circular RNA encodes a miRNA sponge (CDR1as) (Hansen et al., 2013; Memczak et al., 2013), but this appears to be an exception. Although it is conceivable that circularized exons represent tolerable processing errors, their broad conservation across the Drosophilid phylogeny indicates that their production is frequently maintained. Moreover, we identify hundreds of back-splicing events that comprise a substantial fraction of forward-splicing events, especially in specific settings (e.g. heads). Such attributes argue that circularization is a functional regulatory process.

miRNAs are best-known for gene regulation via 3′ UTRs, since Argonaute complexes are susceptible to displacement by ribosomes (Grimson et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2009). Thus, the impact of 5′ UTR and coding miRNA binding sites, while functionally documented, is usually considered limited. However, Drosophila genomes exhibit greater usage of conserved coding miRNA targeting than do mammalian genomes (Schnall-Levin et al., 2010). Our studies reveal that 5′ UTRs and coding regions are the dominant exons involved in Drosophila circular RNAs, and they collectively harbor thousands of well-conserved miRNA binding sites. Since these would no longer be impeded by ribosome occupancy, the collective impact of circular RNAs on miRNA-mediated regulation in Drosophila might be substantial. More generally, we uncover that circularizing coding regions in Drosophila harbor substantially increased density of miRNA target sites with respect to bulk linear coding regions, as well as the linear portions of circularizing transcripts in particular. Therefore, Drosophila circular RNAs are preferred locations for coding-region miRNA targeting.

Even if many RNA circles prove not to have substantial trans-regulatory properties, it is undeniable that back-splicing events frequently represent a substantial fraction of forward-splicing events, and sometimes exceed those of transcripts with linear splicing. Circularization necessarily opposes the production of protein-coding mRNAs, which implies a regulatory event. In particular, our studies highlight potential impact for RNA circularization on neural gene regulation, since this is the predominant in vivo spatial location of this process.

Finally, we provide first evidence for age-related modulation of circular RNA accumulation. Not only does the adult CNS express by far the highest level of circular RNAs, it continues to accumulate circular RNAs during aging. These observations might have implications for RNA circularization during aging and/or senescence processes. For example, it is intriguing to consider whether the collective “sponging” of miRNAs by neural circular RNAs increases with aging, and whether this serves any beneficial purpose, or contributes to functional neural decline. Even if this process proves to be incidental, circular RNAs may serve as a novel class of aging biomarker. Future studies will be aimed at profiling circular RNAs in more detailed aging timecourses, as well as addressing their modulation during aging of the mammalian brain.

Methods

Annotation of Drosophila circular RNAs

We used a large set of Drosophila melanogaster 100nt-PE total RNA-seq libraries that will be described in detail elsewhere (B.R.G. and S.E.C., in preparation). All data are available in the NCBI Short Read Archive under IDs summarized in Table S1. We identified circular RNAs using a custom computational pipeline that uses the STAR read aligner (Dobin et al., 2013). Reads were aligned using the following parameters to identify chimeric transcripts: –chimSegmentMin 20 –chimScoreMin 1 –alignIntronMax 100000 –outFilterMismatchNmax 4 –alignTranscriptsPerReadNmax 10000 – outFilterMultimapNmax 2. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Text, and the scripts are available at https://github.com/orzechoj/circRNA_finder.git.

Circular RNAs were annotated to genomic features by overlapping coordinates of to FlyBase 5.40 gene models, snoRNAs and tRNAs, and repeat annotations from RepeatMasker. Sets of genes with circular isoforms were analyzed for enrichment of Gene Ontology (Ashburner et al., 2000) annotations and modENCODE expression clusters (Roy et al., 2010) using Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Sets of genes were also analyzed for enrichment of FlyAtlas tissue enriched genes (Chintapalli et al., 2007). For each tissue, all genes with enrichment scores of at least 2 were selected.

To assess circle conservation in other species, we utilized 75ntPE total RNA-seq data from D. yakuba and D. virilis heads that will be described in detail elsewhere (P.S., S.S., E.C.L., in preparation). The data are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under GEO-IDs summarized in Table S1. These data were run through the main pipeline and the Dyak r1.2 and Dvir r1.2 genome references. However, due to the shorter read length and potentially incomplete genome annotations in these species, we supplemented circular RNA annotations from these data with direct mapping to a virtual index of intragenic back-splices (see Supplementary Text for details).

Analysis of circular RNA features

We assessed the frequency with which back-spliced reads are mated to reads that are inconsistent with circular RNA interpretation. However, as STAR does not report all such reads of interest, we mapped all mate pairs independently, filtered these to identify reads that spanned back-spliced junctions, and then assessed the properties of back-spliced mate-pairs. A fuller description is provided in the Supplemental Methods.

De-novo motif finding was done using MEME, with the following parameters: -minw 6 -maxw 15 -mod anr. Regions of 500 bp flanking the circular RNAs were searched for motifs. The same parameters were also used to analyze regions flanking 485 “high stringency” circular RNAs reported in (Jeck et al., 2013).

Based on FlyBase 5.40 gene models, genomic features of the circular RNAs that could be assigned to mRNA transcripts were analyzed: length of flanking introns, position in the transcript of the first and last exons of the circular RNA and total number of exons. These numbers were compared to the corresponding numbers from a control set of randomly sampled exon pairs, from the same set of transcripts as those generating the circular RNAs. In this analysis, circular RNAs were stratified according to expression (normalized to host gene mRNA expression).

To assess splicing or retention of internal introns of circular RNAs, we analyzed the mate-pairs of junction-spanning reads. Such reads with spliced mappings were taken as evidence of splicing of the internal introns. If the reads were not spliced, but instead overlapped an annotated intron (by more than 5 bp), they were taken as evidence of intron retention. Using these criteria, for each circular RNA with internal introns the total number of reads supporting splicing and intron retention were tallied up.

For miRNA site analysis, we downloaded whole genome multiple alignments (.maf) of Drosophila genomes from UCSC genome browser and scanned them to identify all instances of conserved 7mers. We parsed these to identify seed matches to conserved miRNAs, star strands, or control sequences, on sense or antisense transcript strands, across various stringencies of species conservation, as appropriate to the analysis.

Expression analysis

Expression levels of circular RNAs were quantified using the number of junction spanning reads. This number was normalized to the total number of reads in the library and to the RPKM of the host mRNA transcript, to obtain an estimate of relative expression [as (# junction spanning reads/million raw reads)/host gene RPKM].

These normalized expression values were also used to quantify increased circular RNA expression in the head time course data. Here special care was taken to make sure that the analysis was not skewed by different numbers of reads in the libraries at the different time points: For example, in a comparison of time points A and B with 90 and 100 million sequenced reads respectively, a circular RNA supported by N reads in both time points will appear to have higher expression levels in time point A. To ensure results were not distorted by library size, we subsampled the data so that all time points had the same number of sequenced reads when analyzing expression differences between time points.

To obtain circular RNAs that accumulate with age, we compared the number of junction spanning reads normalized to library size and host mRNA expression between the head 1 day (6 libraries) and 20 day (libraries) samples. Table S5 contains all circular RNAs with a t-test p-value of < 0.05 and fold change >2.

Molecular biology

We isolated total RNA from Canton S flies raised at 25°C, and purified poly(A)+ RNA using Oligotex mRNA mini kit (Qiagen). To degrade linear RNA, we treated 60 μg of total RNA with 120 units RNAse R (Epicentre) for 45 minutes at 37°C. Northern blots, cDNA preparation and RT-PCRs were performed as described (Miura et al., 2013). Relevant oligo sequences are listed in Table S7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Dobin for helpful discussion of STAR. J.O.W. was supported by the Swedish Society for Medical Research. P.M. was supported by the CIHR. S.E.C. and B.R.G. were supported by the NHGRI modENCODE Project, contract U54-HG006994 (PI SEC) under DOE contract #DE-AC02-05CH11231. E.C.L.’s group was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (#1004721) and NIH R01-GM083300 and R01-NS083833.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Balool HH, Weber D, Liu Y, Wade M, Guleria K, Nam PL, Clayton J, Rowe W, Coxhead J, Irving J, et al. Post-transcriptional exon shuffling events in humans can be evolutionarily conserved and abundant. Genome research. 2011;21:1788–1799. doi: 10.1101/gr.116442.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature genetics. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal-Fluss R, Meyer M, Pamudurti NR, Ivanov A, Bartok O, Hanan M, Evantal N, Memczak S, Rajewsky N, Kadener S. circRNA Biogenesis Competes with Pre-mRNA Splicing. Molecular cell. 2014;56:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Robine N, Samsonova A, Westholm JO, Naqvi A, Hung JH, Okamura K, Dai Q, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Martin R, et al. Deep annotation of Drosophila melanogaster microRNAs yields insights into their processing, modification, and emergence. Genome research. 2011;21:203–215. doi: 10.1101/gr.116657.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Boley N, Eisman R, May G, Stoiber M, Duff M, Booth B, Park S, Suzuki A, Wan K, et al. Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature. 2014a;512:393–399. doi: 10.1038/nature12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JB, Boley N, Eisman R, May GE, Stoiber MH, Duff MO, Booth BW, Wen J, Park S, Suzuki AM, et al. Diversity and dynamics of the Drosophila transcriptome. Nature. 2014b doi: 10.1038/nature12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarco JA, Superina S, O’Hanlon D, Gabut M, Raj B, Pan Q, Skalska U, Clarke L, Gelinas D, van der Kooy D, et al. Regulation of vertebrate nervous system alternative splicing and development by an SR-related protein. Cell. 2009;138:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capel B, Swain A, Nicolis S, Hacker A, Walter M, Koopman P, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell. 1993;73:1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nature genetics. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocquerelle C, Mascrez B, Hetuin D, Bailleul B. Mis-splicing yields circular RNA molecules. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1993;7:155–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danan M, Schwartz S, Edelheit S, Sorek R. Transcriptome-wide discovery of circular RNAs in Archaea. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:3131–3142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski PJ, Zaug AJ, Cech TR. The intervening sequence of the ribosomal RNA precursor is converted to a circular RNA in isolated nuclei of Tetrahymena. Cell. 1981;23:467–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley BR, Brooks AN, Carlson JW, Duff MO, Landolin JM, Yang L, Artieri CG, van Baren MJ, Boley N, Booth BW, et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature09715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Molecular cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Jin L, Zhang F, Sarnow P, Kay MA. Biological basis for restriction of microRNA targets to the 3′ untranslated region in mammalian mRNAs. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2009;16:144–150. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Agarwal V, Guo H, Bartel DP. Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome biology. 2014;15:409. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0409-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 2013;495:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgers V, Perry MW, Hendrix D, Stark A, Levine M, Haley B. Neural-specific elongation of 3′ UTRs during Drosophila development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:15864–15869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112672108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseley JM, Garcia-Casado Z, Pascual M, Paricio N, O’Dell KM, Monckton DG, Artero RD. Noncanonical RNAs from transcripts of the Drosophila muscleblind gene. The Journal of heredity. 2006;97:253–260. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeck WR, Sharpless NE. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK, Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF, Sharpless NE. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Burge CB. A computational analysis of sequence features involved in recognition of short introns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11193–11198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201407298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus CJ, Duff MO, Eipper-Mains J, Graveley BR. Global analysis of trans-splicing in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:12975–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura P, Shenker S, Andreu-Agullo C, Westholm JO, Lai EC. Widespread and extensive lengthening of 3′ UTRs in the mammalian brain. Genome research. 2013;23:812–825. doi: 10.1101/gr.146886.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro JM, Cho KR, Fearon ER, Kern SE, Ruppert JM, Oliner JD, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Scrambled exons. Cell. 1991;64:607–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90244-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Phillips MD, Tyler DM, Duan H, Chou YT, Lai EC. The regulatory activity of microRNA* species has substantial influence on microRNA and 3′ UTR evolution. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:354–363. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Ernst J, Kharchenko PV, Kheradpour P, Negre N, Eaton ML, Landolin JM, Bristow CA, Ma L, Lin MF, et al. Identification of Functional Elements and Regulatory Circuits by Drosophila modENCODE. Science. 2010;330:1787–1797. doi: 10.1126/science.1198374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Stark A, Johnston WK, Kellis M, Bartel DP, Lai EC. Evolution, biogenesis, expression, and target predictions of a substantially expanded set of Drosophila microRNAs. Genome research. 2007;17:1850–1864. doi: 10.1101/gr.6597907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman J, Chen RE, Olsen MN, Wang PL, Brown PO. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman J, Gawad C, Wang PL, Lacayo N, Brown PO. Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PloS one. 2012;7:e30733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ, Kleinschmidt AK. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73:3852–3856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnall-Levin M, Zhao Y, Perrimon N, Berger B. Conserved microRNA targeting in Drosophila is as widespread in coding regions as in 3′UTRs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15751–15756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006172107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Miura P, Westholm JO, Shenker S, May G, Duff MO, Zhang D, Eads B, Carlson J, Brown JB, et al. Global patterns of tissue-specific alternative polyadenylation in Drosophila. Cell reports. 2012;1:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Mohammed J, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Tsai H, Robine N, Westholm JO, Ladewig E, Dai Q, Okamura K, Flynt AS, et al. Diversity of miRNAs, siRNAs and piRNAs across 25 Drosophila cell lines. Genome research. 2014;24:1236–1250. doi: 10.1101/gr.161554.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XO, Wang HB, Zhang Y, Lu X, Chen LL, Yang L. Complementary sequence-mediated exon circularization. Cell. 2014;159:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.