Abstract

Neutrophil trafficking to sites of inflammation is essential for the defense against bacterial and fungal infections, but also contributes to tissue damage in TH17-mediated autoimmunity. This process is regulated by chemokines, which often show an overlapping expression pattern and function in pathogen- and autoimmune-induced inflammatory reactions. Using a murine model of crescentic GN, we show that the pathogenic TH17/IL-17 immune response induces chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 (CXCL5) expression in kidney tubular cells, which recruits destructive neutrophils that contribute to renal tissue injury. By contrast, CXCL5 was dispensable for neutrophil recruitment and effective bacterial clearance in a murine model of acute bacterial pyelonephritis. In line with these findings, CXCL5 expression was highly upregulated in the kidneys of patients with ANCA-associated crescentic GN as opposed to patients with acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Our data therefore identify CXCL5 as a potential therapeutic target for the restriction of pathogenic neutrophil infiltration in TH17-mediated autoimmune diseases while leaving intact the neutrophil function in protective immunity against invading pathogens.

Keywords: GN, immunology, neutrophils, IL-17, chemokines, CXCL5

Neutrophils are the most abundant type of leukocytes in the blood and form an indispensable part of the innate immune system. Their trafficking into peripheral tissues is pivotal in the defense against invading bacterial and fungal pathogens.1 To ensure that neutrophils reach the sites of tissue injury, their recruitment is regulated by the local expression of chemoattractants, including chemokines. However, the infiltration of neutrophils also significantly contributes to end-organ damage in autoimmune diseases mediated by T helper (TH) cell TH17,2 including human and experimental crescentic GN.3,4

Chemokines are a large family of small (8–12 kD) secreted proteins that are identified as attractants of different types of leukocytes, including neutrophils, to sites of infection and inflammation.5 They are produced locally in tissues and act through interaction with specific G protein–coupled receptors that are predominantly expressed on leukocytes. Neutrophil infiltration is mainly mediated by chemokines that have a glutamate-leucine-arginine motif (ELR+ chemokines). In humans, there are seven ELR chemokine ligands with a C-X-C motif (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL7, and CXCL8/IL-8). Their chemotactic effects are mediated via binding to the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2. Mice lack complete homologs of the seven human ELR chemokines and have only five members (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL7, which all bind to the murine CXCR2).6 Interestingly, previous reports show that IL-17A, the master effector cytokine of TH17 cells, induces the expression of the ELR+ chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL57,8 and thereby might drive the recruitment of pathogenic neutrophils in autoimmunity. The development of a therapeutic strategy targeting ELR+ neutrophil–attracting chemokines or their receptors is complicated by an often overlapping expression pattern and function of these molecules in pathogen- and autoimmune-induced inflammatory reactions.9

Here we describe for the first time a nonredundant function of the chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL5 in murine models of crescentic GN and acute bacterial pyelonephritis. CXCL1 mediated early glomerular neutrophil recruitment in the non-T cell–dependent initiation phase of GN, whereas CXCL5 was responsible for the infiltration of pathogenic neutrophils into sites of inflammation in later TH17-dependent phases of the disease. Of note, CXCL5 did not affect neutrophil infiltration and bacterial clearance in a murine model of acute bacterial pyelonephritis, one of the most prevalent kidney infections in humans. These findings suggest that CXCL5 has a unique function in the trafficking of neutrophils in TH17 cell–mediated autoimmunity, but not in the innate immune response. CXCL5 therefore represents an attractive therapeutic target for the restriction of pathogenic neutrophil infiltration in TH17-driven autoimmune diseases without affecting the vital functions of neutrophils in the defense against acute bacterial infections.

Results

Time- and Compartment-Specific Infiltration of Neutrophils in Murine Crescentic GN

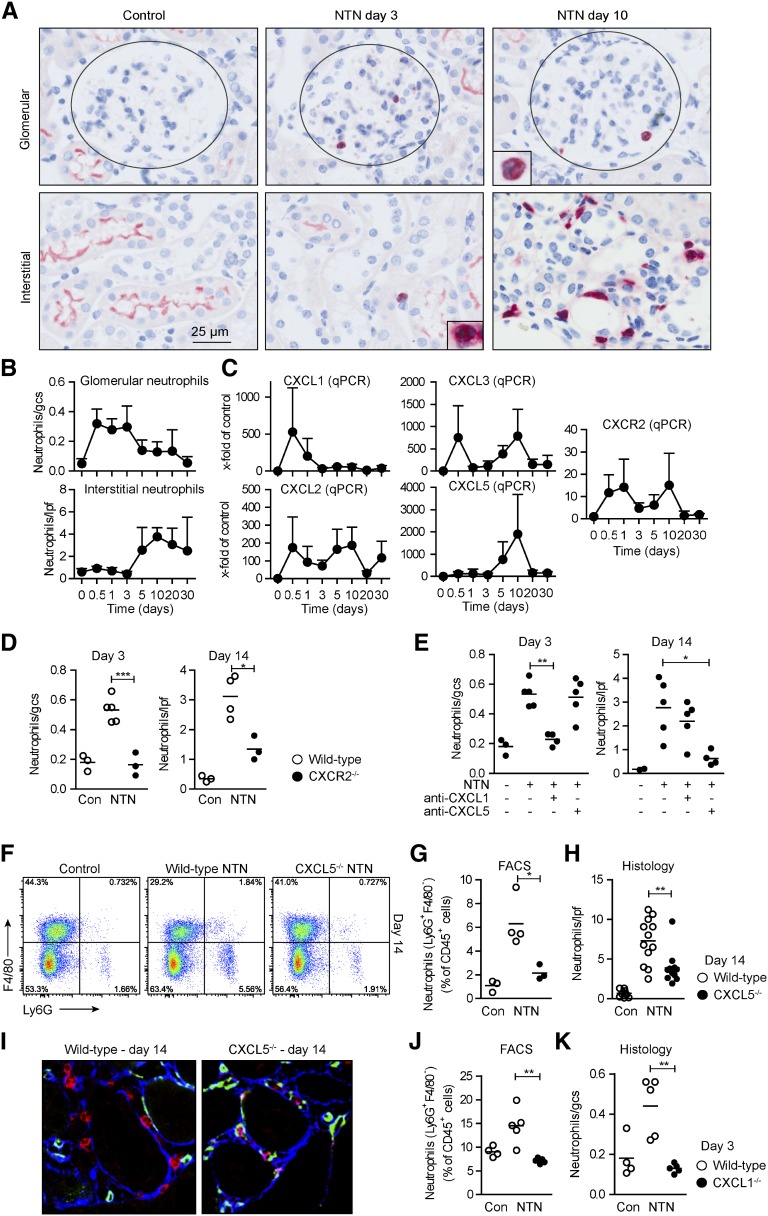

Nephrotoxic nephritis (NTN) is a well characterized model of murine crescentic GN, which is induced by the injection of sheep antiserum raised against kidney cortical components. During the early heterologous phase of the disease, the deposited antibodies result in glomerular complement activation and neutrophil recruitment, which cause substantial glomerular injury and renal dysfunction.10 An adaptive immune response against the foreign sheep protein develops in the subsequent autologous phase (starting from days 3 to 5), resulting in the activation of nephritogenic CD4+ TH17 and TH1 cells in lymphatic organs. First, TH17 cells and, subsequently, TH1 cells migrate into the kidney and promote renal tissue injury.11–13 The role of neutrophils in the T cell–mediated phase (starting from day 5) is largely unknown. We therefore assessed the time course of renal neutrophil infiltration using immunohistochemical staining for the neutrophil marker Gr1 (Ly6C/Ly6G) (Figure 1A). In the early stage of nephritis (until day 3), neutrophils were mainly found in the glomerulus (Figure 1, A and B). The infiltration of neutrophils into the tubulointerstitial area started at day 5, peaked around day 10, and then declined (Figure 1, A and B). This demonstrates a previously unknown time- and compartment-specific recruitment of neutrophils into the kidney.

Figure 1.

CXCL1 and CXCL5 have unique functions in the time- and compartment-specific infiltration of neutrophils in crescentic GN. (A) Immunohistochemistry of kidney sections stained for the neutrophil marker GR1 at indicated time points after nephritis induction. Inserts demonstrate the polymorphonuclear morphology of GR1+ cells (neutrophils). (B) Quantification of tubulointerstitial (per low-power field [lpf]) and glomerular (per glomerular cross-section [gcs]) PMN infiltration in the course of nephritis (n=3–6 per time point). (C) RT-PCR analysis of renal CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCR2 mRNA expression (n=4–6 per time point). (D) Quantification of tubulointerstitial and glomerular PMNs in nephritic WT and CXCR2−/− mice at day 3 or day 14 after induction of the disease (n=3–5 per time point). (E) Quantification of tubulointerstitial and glomerular PMNs in nephritic WT mice at day 3 or 14 of nephritis after administration of anti-CXCL1, anti-CXCL5, or isotype rat-IgG2B antibodies (n=3–5 per time point). (F) FACS analysis of renal leukocytes from nephritic WT and CXCL5−/− mice stained for the PMN marker Ly6G at day 14. Plots are representative of three independent experiments. (G and H) Quantification of neutrophils from FACS analysis (G) and quantification of tubulointerstitial PMNs from GR1 stained kidney sections (H) in nephritic WT and CXCL5−/− mice 14 days after nephritis induction. (I) Immunofluorescence staining of nephritic kidney section (day 14) of WT and CXCL5−/− mice using anti-CD31 (green/endothelial cells), anti-Ly6G (red/PMNs), and collagen type (blue/basement membrane). (J and K) Quantification of renal neutrophils by FACS analysis (J) and quantification of glomerular PMNs from GR1 stained kidney sections (K) in nephritic WT and CXCL1−/− mice 3 days after nephritis induction. Symbols/bars represent means±SDs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Original magnification, ×200. Con, control.

CXCL1 and CXCL5 Have Unique Functions in the Recruitment of Neutrophils in Crescentic GN

One important prerequisite for the infiltration of neutrophils into sites of inflammation is the expression of ELR+ chemokines, namely CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL7, which act via the chemokine receptor CXCR2. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the renal cortex revealed that CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL3 mRNA expression was strongly upregulated in the early stages of nephritis (12 and 24 hours) (Figure 1C). Renal CXCL7 expression was low throughout the disease course (data not shown). CXCL1 expression rapidly declined to the baseline level by day 3. By contrast, CXCL5 mRNA expression was not increased at early time points but markedly increased from day 5 onward, with maximum expression levels at day 10 (detectable after approximately 25 PCR cycles). Chemokines can be modified post-translationally by proteolytic cleavage in order to achieve the active form and stored intracellular, therefore, a discrepancy between local mRNA level and protein level/activity might occur. However, our attempts to quantify renal CXCL5 protein levels in nephritic mice by ELISA failed because of high background signals when using CXCL5 knockout (KO) mice as negative controls (data not shown).

Renal mRNA expression of CXCR2 was characterized by a bimodal course reaching two maxima after 24 hours and 10 days (Figure 1C). In line with this, glomerular and tubulointerstitial neutrophil recruitment was reduced in nephritic CXCR2−/− mice at days 3 and 14 (Figure 1D). This showed that CXCR2 drives both the “early” and “late” waves of neutrophil recruitment.

To elucidate whether the expression patterns of CXCL1 and CXCL5 might result in different functions of these chemokines in the disease course, we performed early (until day 3) and late (days 9 to 14) in vivo neutralization with specific anti-CXCL1 or anti-CXCL514 antibodies. In line with their temporal expression profile, neutralization of CXCL1 resulted in ameliorated glomerular neutrophil infiltration at day 3, whereas anti-CXCL5 antibody treatment at day 9 resulted in significantly reduced tubulointerstitial neutrophil recruitment at day 14 (Figure 1E). Accordingly, renal FACS analysis revealed a reduction in CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in nephritic CXCL5−/− mice at day 14 (Figure 1, F and G), but not at day 3 (Supplemental Figure 1A). Likewise, tubulointerstitial neutrophil accumulation was significantly decreased in nephritic CXCL5−/− mice at day 14 (Figure 1H), but not at day 3 (Supplemental Figure 1B). Immunofluorescence staining revealed that neutrophils in nephritic CXCL5−/− mice had a reduced capacity to exit the peritubular capillaries and to enter the tubulointerstitial space (Figure 1I).

By comparison, the infiltration of T cells and macrophages/dendritic cells was not significantly affected by CXCL5 deficiency or anti-CXCL5 treatment (Supplemental Figure 2, A–H, J). Furthermore, neutrophil, monocyte, CD4+, and CD8+ T cell abundance in the blood, spleen, and kidney under homeostatic and nephritic conditions was not significant different between wild-type (WT) and CXCL5−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 3). In addition, kidney morphology and function were not affected by CXCL5 deficiency under basal conditions (Supplemental Figure 4). This indicates that reduced neutrophil abundance in the kidney of nephritic CXCL5−/− animals was not a consequence of a developmental defect in the hematopoietic system or the kidney, but rather represents reduced recruitment to the inflamed tissue in CXCL5−/− mice.

To analyze the role of CXCL1 in the early infiltration of neutrophils into the kidney using a second, independent approach, we induced NTN in WT and CXCL1-deficient mice. In accordance with our anti-CXCL1 neutralization data, neutrophil recruitment was reduced in nephritic CXCL1−/− mice at day 3, thus underscoring the importance of this chemokine in the early course of nephritis (Figure 1, J and K).

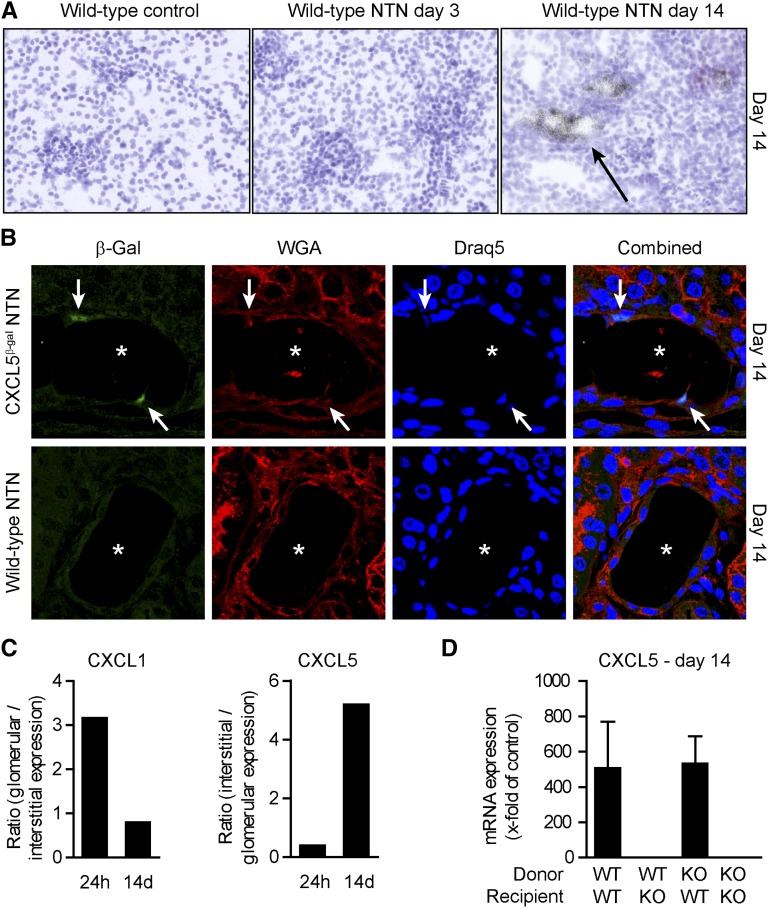

Kidney Tubular Cells Produce CXCL5 in Late Crescentic GN

To localize renal CXCL5 expression, we performed in situ hybridization experiments. CXCL5 expression was clearly detectable in tubular cells 14 days after nephritis induction, but not at day 3 or in control mice (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

CXCL5 is expressed by kidney tubular cells. (A) Representative CXCL5 in situ hybridizations of nephritic mice show that CXCL5 expression colocalizes with kidney tubular cells (arrow) at day 14. (B) Kidney sections of nephritic WT and CXCL5β-Gal are stained for β-Gal with specific antibodies (AF488; green), wheat germ agglutinin (TexasRed; red), and nuclear marker draq5 (blue) (arrow, β-Gal–positive cells; asterisk, tubulus lumen). (C) RT-PCR analysis of compartment-specific CXCL1 and CXCL5 expression (laser-microdissected glomeruli versus tubulointerstitium) at 24 hours and 14 days after induction of nephritis. Data are presented as the ratio of glomerular to tubulointerstitial expression and vice versa (n=3 per group). (D) RT-PCR analysis of renal CXCL5 expression in BM chimeric nephritic mice at day 14 (n=4–6 per group). Bars represent means±SDs.

Replacement of the CXCL5 gene by a β-galactosidase (β-Gal) gene in CXCL5-deficient mice enabled us to indirectly assess the renal CXCL5 protein expression by β-Gal detection. Nuclear β-Gal staining was observed exclusively in tissues collected from nephritic CXCL5−/− mice (Figure 2B). In line with the CXCL5 mRNA expression pattern, β-Gal–positive cells were detected in the tubular epithelium of nephritic mice (Figure 2B).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of glomerular and tubulointerstitial tissue samples isolated from nephritic mice using laser microdissection at days 3 and 14 after induction of NTN revealed that CXCL5 mRNA expression was predominantly upregulated at day 14 in the tubulointerstitial compartment, as indicated by the tubulointerstitial to glomerular expression ratio (Figure 2C). CXCL1 mRNA was mainly expressed in glomeruli at day 3, whereas glomerular and tubulointerstitial expression were at control levels at day 14 (Figure 2C).

To study whether CXCL5 is mainly produced by renal tissue cells, we generated bone marrow (BM) chimeras using WT and CXCL5−/− mice as donors (Figure 2D). Independent of the BM transplant used, 14 days after induction of nephritis, high CXCL5 mRNA expression levels were only present in animals with WT renal tissue cells. An approximately 500-fold increase in CXCL5 mRNA expression was found in both WT recipient mice transplanted with WT BM or CXCL5−/− BM compared with control mice. By contrast, CXCL5 mRNA expression in CXCL5−/− mice receiving WT BM or CXCL5−/− BM was not elevated (Figure 2D). As control, we used WT mice carrying the CD45.2 allele as recipients. Six weeks after transplantation, >90% of blood leukocytes, >98% of BM leukocytes, and >90% of splenic leukocytes expressed the phenotypic marker of the transplanted BM (n=6).

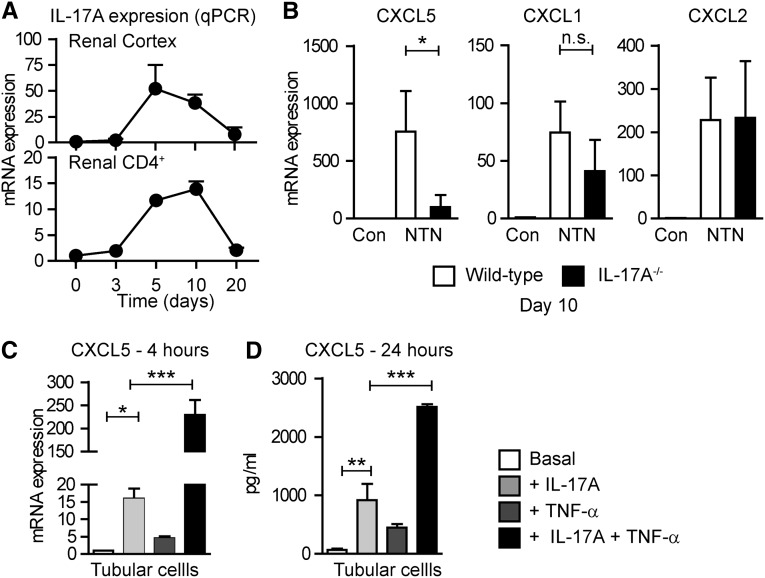

The TH17/IL-17 Immune Response Mediates Renal CXCL5 Expression in Crescentic GN

The striking temporal association between CXCL5 expression, tubulointerstitial neutrophil infiltration (Figure 1, A–H), and the recruitment of CD4+ TH17 cells into the kidney at day 10 (Figure 3A, Supplemental Figure 5) suggest a functional relationship. To determine whether IL-17A drives CXCL5 expression in vivo, we induced nephritis in IL-17A−/− mice. WT animals showed strong upregulation of CXCL5 mRNA at day 10 after nephritis induction, whereas IL-17A−/− mice displayed reduced upregulation (WT versus IL-17A−/−, P<0.01) (Figure 3B). By contrast, CXCL1 and CXCL2 expression was not significantly altered in nephritic IL-17A−/− mice (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

IL-17A drives renal CXCL5 expression. (A) RT-PCR analysis of renal IL-17A expression in the course of nephritis (n=5–6 per time point). RT-PCR analysis of IL-17A mRNA expression in FACS-sorted renal CD4+ T cells isolated from nephritic kidneys at days 3, 5, 10, and 20. (B) RT-PCR analysis of chemokine mRNA expression in nephritic WT (n=6) and nephritic IL-17A−/− mice (n=6) at day 10. (C) RT-PCR for CXCL5 expression in murine kidney tubular cells upon stimulation with IL-17A (10 ng/ml), TNF-α (10 ng/ml), and IL-17A+TNF-α for 4 hours. (D) CXCL5-specific ELISA from supernatant of stimulated tubular cells after 24 hours. Bars represent means±SDs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Con, control.

IL-17A and TNF-α Synergistically Induce CXCL5 Expression in Mouse Tubular Cells

Given the high renal expression of CXCL5, predominantly in tubular cells (Figure 2, A and B), we investigated whether IL-17A drives CXCL5 expression in kidney tubular cells. Because the biologic effects of IL-17A are mediated by activation of the IL-17 receptors A and C, we demonstrated the presence of these receptors in mouse tubular cells by RT-PCR (Supplemental Figure 6A). Next, we demonstrated that IL-17A induces CXCL5 mRNA and protein production in tubular cells in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Figure 6B), whereas IL-17F and IFN-γ had no effect (Supplemental Figure 6C).

The signal transduction pathway mediated by IL-17A is still incompletely characterized but involves NF-κB and extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) activation.15 Therefore, it is of interest that the combination of IL-17A and TNF-α synergistically amplified the RNA expression and protein secretion of CXCL5 (Figure 3, C and D), and synergistically induced ERK activation but not NF-κB signaling in tubular cells (Supplemental Figure 6D). Although the in vivo importance of this finding remains to be elucidated, the time kinetic of renal IL-17A (Figure 3A) and TNF-α expression in NTN (Supplemental Figure 6E) is consistent with CXCL5 formation in the inflamed kidney.

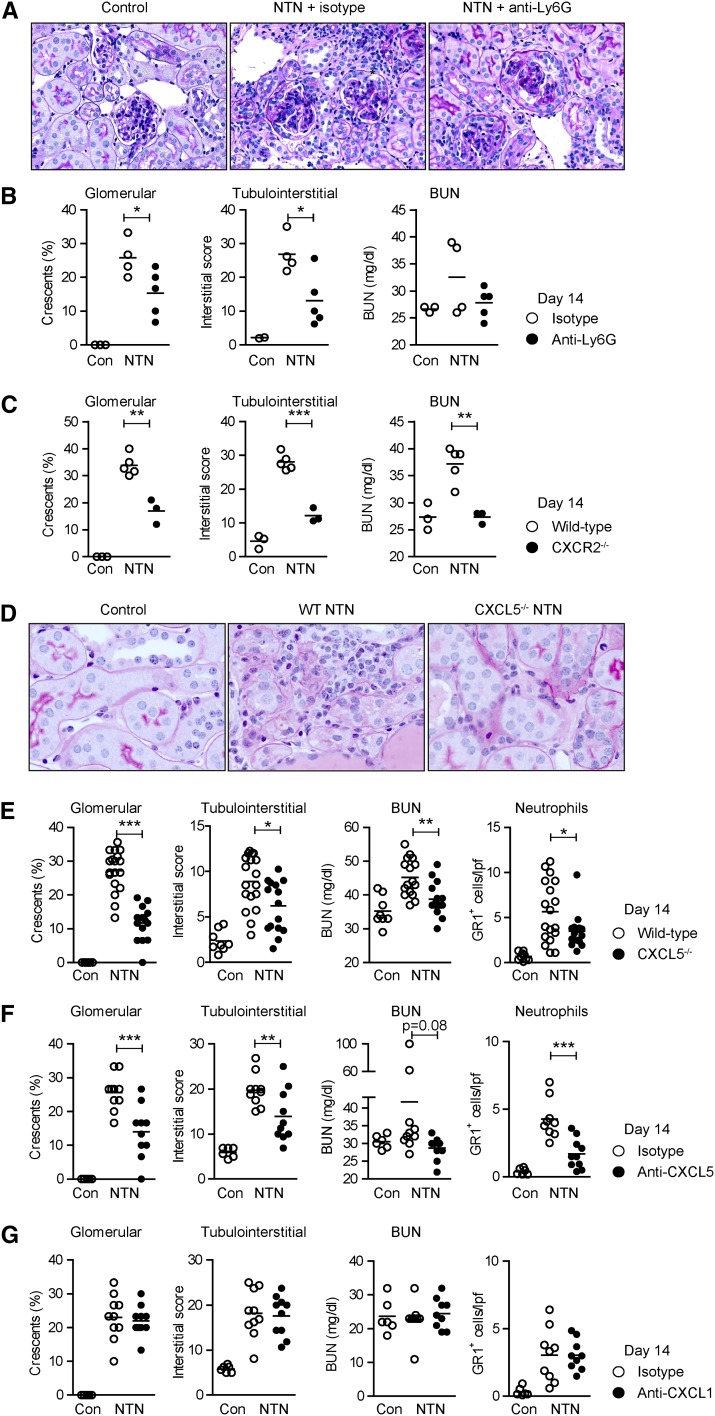

Tubulointerstitial Infiltration of CXCR2+ Neutrophils Promotes Renal Tissue Injury

To investigate the functional importance of the observed tubulointerstitial neutrophil recruitment, we depleted neutrophils in nephritic mice from days 9 to 14 by using a Ly6G-specific mAb16 (Supplemental Figure 7). Neutrophil depletion significantly reduced tubulointerstitial tissue injury and to a lesser degree glomerular crescent formation, demonstrating the pathogenic role of neutrophils during the TH17 cell–mediated phase of the disease (Figure 4, A and B). Levels of BUN, a marker inversely correlated with renal function, were slightly but not significantly reduced (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The CXCL5/CXCR2 axis promotes renal tissue injury. (A) Representative photographs of PAS-stained kidney sections of mice±neutrophil depletion (from days 9 to 14) at day 14 after induction of nephritis. (B) Quantification of glomerular crescent formation, tubulointerstitial damage, and BUN levels at day 14. (C) Quantification of renal tissue damage and renal function assessed by BUN levels at day 14 in WT and CXCR2−/− mice. (D) Representative photographs (PAS staining) of the tubulointerstitial compartment of control, nephritic WT, and nephritic CXCL5−/− mice at day 14. (E) Quantification of glomerular crescent formation, tubulointerstitial damage, BUN levels, and renal neutrophil recruitment 14 days after disease induction. (F and G) Quantification of glomerular crescent formation, tubulointerstitial damage, BUN levels, and neutrophil infiltration in animals treated with anti-CXCL5 (or IgG2B isotype antibody) (F) and anti-CXCL1 (or IgG2A isotype antibody) (G) 14 days after disease induction. Bars represent means±SDs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Original magnification, ×200 in A; ×400 in D. Con, control; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff.

Next, we showed that CXCR2-deficient mice developed less severe nephritis, in terms of renal tissue damage and BUN levels at day 14 (Figure 4C). This is in line with reduced neutrophil infiltration in nephritic CXCR2−/− mice (Figure 1D). The recruitment of CD3+ T cells and mononuclear phagocytes was not significantly affected by CXCR2 deficiency (Supplemental Figure 2I). Mouse anti-sheep globulin–specific IgG, subclass IgG1, subclass IgG2a, and IgG2b titers were unaffected in nephritic CXCR2−/− mice compared with the WT group (Supplemental Figure 8F).

Targeting of CXCL5 Reduces Renal Tissue Damage in the T Cell–Mediated Stage of Crescentic GN

To investigate whether CXCL5 contributes to renal tissue injury, nephritis was induced in CXCL5−/− and WT mice. At day 14, CXCL5−/− mice showed significantly less tubulointerstitial and glomerular injury compared with controls (Figure 4, D and E). In addition, BUN levels were reduced in nephritic CXCL5−/− mice compared with nephritic WT mice at day 14 (P<0.001; Figure 4E). Albuminuria was upregulated in all nephritic groups, but was not significantly different between nephritic WT and CXCL5 KO mice at day 14 (urine albumin/creatinine ratio: WT control [n=6], 0.1±0.1; WT NTN [n=8], 15.8±4.7; CXCL5−/− NTN [n=10], 9.7±8.9).

Treatment of nephritic mice with a neutralizing anti-CXCL5 antibody at day 9 significantly reduced renal tissue injury at day 14 (Figure 4F). The more pronounced protection of nephritic CXCL5−/− mice compared with anti-CXCL5–treated animals, in terms of BUN levels, is likely the result of a complete absence of CXCL5 in the KO mice and the timely restricted CXCL5 neutralization from days 9 to 14. The beneficial effect of neutrophil and CXCL5 targeting on glomerular injury might reflect reduced renal PMN infiltration.

By contrast, the treatment of nephritic mice with a neutralizing anti-CXCL1 antibody at day 9 (nephritic controls received IgG2a isotype control antibodies) had no effect on the clinical outcome of the disease at day 14 (Figure 4G).

Serum titers of anti-sheep IgG, IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b antibodies directed against the nephritogenic antigen and semiquantitative scoring of glomerular sheep and mouse IgG deposition revealed no differences between nephritic WT and CXCL5−/− mice (Supplemental Figure 8, A–E). Moreover, IL-17 and IFN-γ production of sheep IgG-stimulated splenocytes is not impaired in nephritic CXCL5 KO mice compared with nephritic WT mice at day 14 (Supplemental Figure 9), indicating that the absence of CXCL5 did not impair the systemic immune response against the nephritogenic antigen.

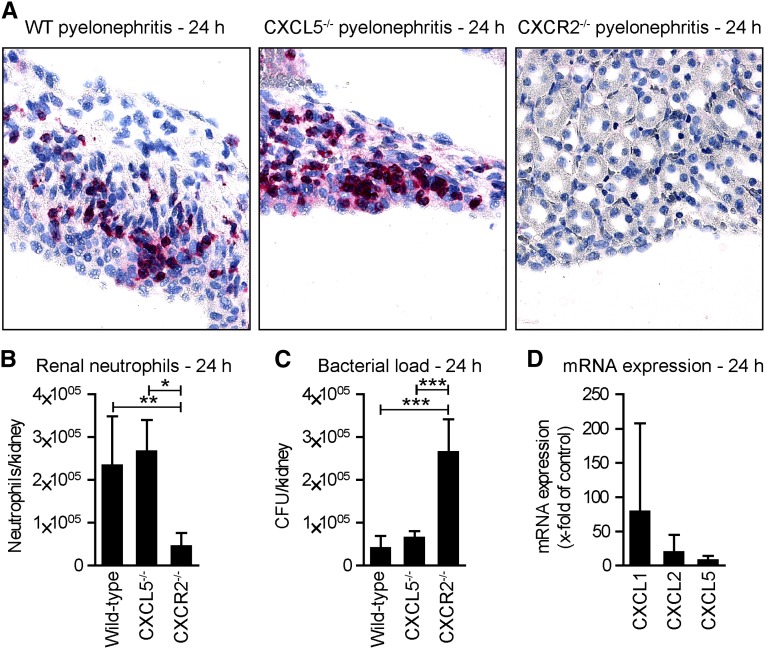

CXCL5 Is Dispensable for Neutrophil Recruitment and Bacterial Clearance in a Murine Model of Acute Bacterial Pyelonephritis

We next studied the role of CXCL5 in neutrophil trafficking and function in a well established model of acute bacterial pyelonephritis. This model is induced by transurethral instillation of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536 (UPEC),17 which invades the kidney and is subsequently cleared by recruited neutrophils. A massive infiltration of neutrophils into the kidney (assessed by immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry) was detected in WT mice 24 hours after UPEC infection (Figure 5, A and B). Of note, neutrophil recruitment was not affected by CXCL5 deficiency, whereas neutrophils were strongly reduced in infected CXCR2-deficient mice. In line with the pivotal role of neutrophils in bacterial clearance, the numbers of CFUs in the kidneys were significantly higher in CXCR2−/− mice compared with WT and CXCL5−/− animals (Figure 5C). Renal expression of CXCL1, and to a lesser degree of CXCL2, was markedly enhanced, whereas CXCL5 was only slightly upregulated 24 hours after infection (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

CXCL5 is dispensable for neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in a murine model of acute bacterial pyelonephritis. (A) Representative immunohistochemistry for the neutrophil marker GR-1 24 hours after transurethral instillation of UPEC. (B) Quantification of FACS analyses of renal PMNs (CD45+, GR-1HI, F4/80−, CD11c−), (numbers represent total cells per kidney; n=5–6 per group). (C) CFU per kidney at 24 hours (n=5–6). (D) RT-PCR analysis of renal CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5 expression 24 hours after UPEC infection. Bars/symbols represent means±SDs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; *** P<0.001. Original magnification, ×400.

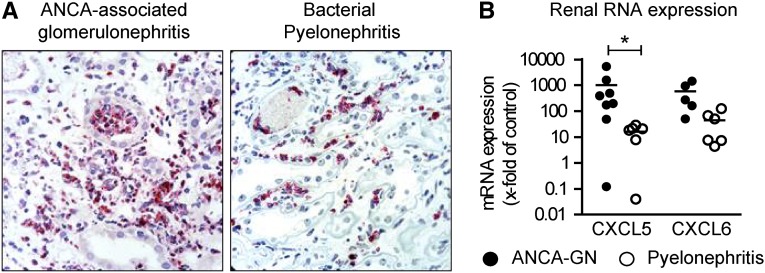

Renal CXCL5 Expression in Patients with ANCA-Associated GN and Acute Bacterial Pyelonephritis

We isolated RNA from renal biopsies and performed real-time PCR to analyze the renal expression of neutrophil-attracting chemokines in patients with acute ANCA-associated GN, the most common form of crescentic GN in humans, and in patients with acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Although neutrophil recruitment is common to ANCA-associated GN but even stronger in acute pyelonephritis (Figure 6A), upregulation of renal tissue CXCL5 expression was more profound in ANCA-associated GN (1013-fold; Figure 6B) compared with acute pyelonephritis (16-fold; Figure 6B). Similar results were obtained for CXCL6, which is a close homolog to human CXCL5.6 These results suggest a predominant role of CXCL5 in human autoimmune disease, but not in acute bacterial infection. Table 1 provides the clinical characteristics of the included patients.

Figure 6.

CXCL5 expression in patients with ANCA-associated GN and acute bacterial pyelonephritis. (A) Representative PMN staining (proteinase 3) in renal biopsies of patients with ANCA-associated GN and acute bacterial pyelonephritis. (B) RT-PCR analysis of renal chemokine mRNA expression (n=6–8 per group). Bars represent means±SDs. *P<0.05. Original magnification, ×990.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with acute ANCA-associated GN and bacterial pyelonephritis

| Patient | Age (yr) | Sex | ANCA Type | PR3/MPO ELISA (U/ml) | Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | Proteinuria (mg/24 h) | Immunosuppression before Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | Man | pANCA | MPO 32.6 | 2.7 | 5550 | No |

| 2 | 67 | Man | pANCA | MPO 17.2 | 1.6 | 1130 | No |

| 3 | 62 | Man | pANCA | MPO 34 | 2.5 | 580 | Steroid |

| 4 | 83 | Man | cANCA | PR3 109 | 4.8 | Anuric | Steroid + CyP |

| 5 | 47 | Man | cANCA | PR3 26.5 | 1.6 | 3000 | No |

| 6 | 41 | Woman | cANCA | PR3 >200 | 1.7 | 1730 | No |

| 7 | 18 | Woman | cANCA | PR3 >200 | 0.6 | 430 | No |

| 8 | 76 | Man | cANCA | PR3 >200 | 3.2 | 760 | Steroid |

| 9 | 80 | Woman | Negative | Not assessed | 5.5 | 900 | Steroid |

| 10 | 39 | Woman | Negative | Not assessed | 1.2 | Not assessed | No |

| 11 | 64 | Woman | Negative | Not assessed | 4.8 | Not assessed | No |

| 12 | 71 | Man | Negative | Not assessed | 5.0 | 490 | No |

| 13 | 50 | Man | Negative | Not assessed | 10.2 | >300 | No |

| 14 | 50 | Man | Negative | Not assessed | 6.8 | >3000 | No |

Clinical characteristics of patients with acute ANCA-associated GN (patients 1–8) and acute pyelonephritis (patients 9–14) at the time of renal biopsy. pANCA, perinuclear ANCA; cANCA, cytoplasmic ANCA; PR3, proteinase 3; MPO, myeloperoxidase; CyP, cypionate.

Discussion

In recent years, a large number of studies have established the crucial role of TH17 cells in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases,7,18–20 including proliferative and crescentic GN.3,11,21,22 Consequently, the findings from animal models have been translated into clinical practice, and IL-17A and related cytokines have been successfully targeted for treatment of psoriasis23 and Crohn’s disease.24

However, the mechanisms by which the TH17 immunity directly contributes to end-organ damage still remain to be fully elucidated. TH17 cells produce a variety of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, TNF-α, and GM-CSF, which drive the recruitment of neutrophils to sites of inflammation and thereby promote tissue injury by mechanisms that are thus far incompletely understood.7 Recent studies indicate that ELR+ chemokines play a pivotal role in this process and might therefore represent an attractive target for the prevention of neutrophil-induced tissue injury.25–27 This approach is complicated by an often overlapping/redundant expression pattern and function of chemokines in autoimmune and infectious disease.5 Targeting of chemokines in order to reduce pathogenic neutrophil infiltration in TH17-mediated autoimmunity might therefore impair defense against microbial pathogens.

Recent data by the Chou et al. and McDonald et al. suggest that neutrophil chemoattractants might have less redundant functions in the recruitment of neutrophils in vivo than previously thought.28,29 To investigate the role of the TH17 immune response for neutrophil recruitment and function in detail, we performed time-kinetic analyses in a well characterized TH17-dependent model of crescentic GN (NTN).30 Although NTN does not represent a human disease in all aspects of its pathophysiology (e.g., with respect to immune complex–GN, anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis, or ANCA-associated GN), it remains one of the most efficient mouse model of crescentic GN.31,32 Neutrophils showed a time- and compartment-specific migratory behavior during crescentic GN, suggesting that the interstitial “second wave” of neutrophil infiltration is promoted by renal TH17 cells.

It is generally thought that IL-17A, the major effector cytokine of the TH17 immune response, induces the expression of all neutrophil-attracting ELR+ chemokines in a redundant manner.25,26,33 In murine crescentic GN, however, we unexpectedly found that the expression of CXCL1 and CXCL2 was upregulated until day 3 and then declined even before infiltration of the first TH17 cells. By striking contrast, CXCL5 expression peaked 10 days after induction of the disease and was predominantly expressed by resident tubular cells when the renal TH17 immune response had reached its maximum level. In line with this, IL-17A resulted in a strong upregulation of CXCL5 mRNA and protein expression in murine tubular epithelial cells in vitro, which is further enhanced in the presence of TNF-α, potentially as a consequence of synergistic activation of the ERK signaling pathway. This finding is in accordance with a recent report by Liu et al. showing that CXCL5 mRNA is induced by IL-17A in alveolar epithelial cells.26 To further support our hypothesis that IL-17A (produced by renal TH17 cells) is directly involved in the induction of CXCL5 expression in tubular cells in vivo, the generation of mice that are deficient in the IL-17 receptors A and C or in the IL-17 receptor adaptor protein connection to IκB kinase and stress-activated protein kinases,34 specifically in renal tubular cells, would be of great interest.

IL-17A promoted renal CXCL5 expression and neutrophil infiltration in NTN, whereas CXCL1 and CXCL2 expression was IL-17A independent. These data further point to nonredundant roles of CXCR2 ligands in the attraction of neutrophils to the kidney, most likely resulting from the temporal and spatial segregation of their expression. CXCL1 and CXCL5 in vivo neutralization experiments indeed confirmed that early glomerular neutrophil migration is mainly driven by CXCL1, whereas the second wave of interstitial neutrophil infiltration is strongly dependent on IL-17A–induced CXCL5. Our finding is consistent with a recent study in a model of moderate airway inflammation in CXCL5−/− mice showing that neutrophil infiltration into the inflamed tissue was dependent on CXCL5.27 In contrast with a study by Mei et al. that indicates that enterocyte-derived CXCL5 in the gut regulates local IL-17A levels and contributes to CXCR2-dependent neutrophil homeostasis,35 our study did not show any indication of a role for CXCL5 in the kidney under noninflammatory conditions. The time-dependent role of CXCL5 in GN is further emphasized by the finding that CXCL5−/− mice and anti-CXCL5–treated WT animals displayed an ameliorated disease course at day 14, but not at day 3.

To determine whether the blockade of CXCL5 and CXCR2 generally interferes with neutrophil infiltration, we induced acute bacterial pyelonephritis in WT, CXCL5−/−, and CXCR2−/− mice. In this model, the antibacterial defense relies on the rapid recruitment of neutrophils. As reported, neutrophil trafficking and bacterial clearance critically depend on CXCR2, which is most likely activated by locally expressed CXCL1 and CXCL2,17,36–39 making CXCR2 an unfavorable candidate for therapeutic targeting in autoimmunity. By contrast, CXCL5 deficiency did not affect early neutrophil infiltration and bacterial clearance in this model of acute bacterial pyelonephritis.

A recent study in a murine model of ANCA-associated GN demonstrated that IL-17A–producing TH17 effector cells directly induce renal inflammation by effector responses involving neutrophils.40 Moreover, the first studies in human ANCA-associated GN suggest a prominent role for TH17/IL-17 responses in this form of crescentic GN.4,41 To examine whether our findings are relevant to human disease, we assessed the renal CXCL5 mRNA expression in patients with acute ANCA-associated GN and acute bacterial pyelonephritis, which are both characterized by neutrophil recruitment. In line with the results from our animal models, CXCL5 expression was much higher in renal biopsy specimens from patients with autoimmune-mediated ANCA-associated GN compared with those with acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Interestingly, van der Veen et al. recently reported an increased renal CXCL5 expression in a murine model of anti-myeloperoxidase IgG/LPS-induced crescentic GN, further supporting the role of CXCL5 in autoimmune-mediated ANCA disease.42 The similar expression pattern of CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5 during the course of the disease (assessed at two time points) might be a consequence of the coapplication of LPS in this model.

In conclusion, our study provides the first evidence for a previously unknown nonredundant effector mechanism of the TH17 immune response in experimental crescentic GN involving T cell–derived IL-17A–, CXCL5–, and CXCR2–bearing neutrophils that promote renal tissue injury. By contrast, CXCL5 seems to be dispensable for maintaining neutrophil-mediated innate immune surveillance. However, the potential renal functional benefit of an intervention to target CXCL5 in established crescentic GN remains to be fully elucidated.

Concise Methods

Animals

CXCR2−/− and IFN-γ−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). IL-17A–deficient mice were provided by Yoichiro Iwakura (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), CXCL5-deficient mice were provided by the Max Plank Institute for Infection Biology (Berlin, Germany)43 and CXCL1-deficient mice were provided by S. Lira (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY). All KO mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for at least 10 generations. All mice were raised under specific pathogen-free conditions. Animal experiments were performed according to national animal care and ethical guidelines, and were approved by local ethical committees.

Induction of NTN and Functional Studies

NTN was induced in male mice aged 8 to 10 weeks by intraperitoneal injection of 0.6 ml of nephrotoxic sheep serum per mouse, as previously described.30 Controls were injected intraperitoneally with an equal amount of nonspecific sheep IgG. Urinary albumin excretion was determined by standard ELISA analysis (Mice-Albumin Kit; Bethyl, Montgomery, TX), whereas urinary creatinine and serum BUN were measured using standard laboratory methods. For neutralization/depletion experiments, anti–Ly6G-Ab (clone 1A8),16 anti-CXCL1 Ab (clone 48415; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN),14 or anti-CXCL5 Ab (clone 61905; Leinco Technologies, St. Louis, MO)14 was used at 100 μg per mouse (intraperitoneally). Nephritic control mice in interventional studies received 100 μg rat IgG2A (clone 54447; R&D Systems) or rat IgG2B (clone 61905; Leinco Technologies) antibodies intraperitoneally. Anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 antibodies were given either the day before NTN induction in the case of early neutralization studies (analysis was performed at day 3) or at day 9 in the late stages of the interventional experiments (analysis was performed at day 14).

Acute Bacterial Pyelonephritis Model

Female mice aged 8 to 12 weeks were infected by transurethral instillation of 1×109 UPEC. Three hours later, the procedure was repeated to induce pyelonephritis. Twenty-four hours after infection, the number of ascended bacteria was quantified by scoring CFUs after overnight culture of kidney collagenase digest as previously described.17

Real-Time RT-PCR Analyses

Total RNA of the renal cortex was prepared according to standard laboratory methods. RNA from microdissected tissues was isolated using the RNA Nano prep kit (PALM, Bernried, Germany) as previously described.44 Real-time PCR was performed on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as described.45 In brief, the CXCL5 cRNA probe was labeled with α[35S]UTP (1250 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) of subcloned cDNA corresponding to nucleotides 208–532 of cDNA sequence NM_009141.2. In situ hybridization was performed on 16-µm cryosections using the 35S-labeled antisense and sense RNA probes. Sections were dipped into Kodak NTB nuclear track emulsion and exposed for 3 weeks; after development, sections were stained with Mayer’s hemalaun.

Morphologic Analyses

Glomerular crescent formation was assessed in 30 glomeruli per mouse in a blinded fashion in paraffin sections stained with periodic acid–Schiff.45 To assess tubulointerstitial injury, photographs of four nonoverlapping cortical areas from kidney sections stained with periodic acid–Schiff were taken per mouse and counted in low-magnification fields (×200). The interstitial area was then determined by superimposing the photographs with a grid containing 40 points and by counting the matches of points with interstitial tissue (excluding glomeruli, blood vessels, and tubules) in a blinded fashion. Dividing the positive matches of four photographs by 160 provided the percentage of positive tissue equal to the interstitial injury score.11,45

For immunohistochemical stainings, paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with the following antibodies: GR-1 (1:50, Ly6 G/C, NIMP-R14; Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands), CD3 (1:1000, A0452; Dako, Germany), F4/80 (1:400, BM8; BMA, Germany), MAC-2 (1:1000, M3/38; Cedarlane, ON, Canada), sheep IgG/mouse IgG (both Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), and proteinase 3 to detect PMN in humans. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubation with proteinase type XXIV (5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 15 minutes at 37°C (F4/80, GR1, sheep IgG/mouse IgG) or by microwave antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (DAKO 52367), pH 6.1, for 25 minutes (CD3, MAC-2). Nuclear β-Gal was revealed after protease-mediated antigen retrieval using a polyclonal antibody (Europa Bioproducts, Cambridge, UK). Slides were counterstained with wheat germ agglutinin (Vector, Auckland, New Zealand) and draq 5 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Tissue sections were developed with the Vectastain ABC-AP kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Glomerular GR1+, MAC-2+, and CD3+cells in 30 glomerular cross-sections and tubulointerstitial F4/80+ and CD3+ cells in 30 high-power fields (×400) per kidney were counted in a blinded manner. To quantify tubulointerstitial GR1+ cells, at least 20 low-power fields (×200) were counted. All slides were evaluated under an Axioskop light microscopy (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and photographed with an Axiocam HRc (Zeiss) or by confocal microscopy with a LSM 510 meta microscope using the LSM software.

Isolation of Leukocytes from Kidney and Spleen

Previously described methods for leukocyte isolation from murine kidneys were used.30 In brief, kidneys were finely minced and digested for 45 minutes at 37°C with 0.4 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Spleens were minced to isolate splenocytes. Both cell suspensions were sequentially filtered through 70-µm and 40-µm nylon meshes and washed with HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Invitrogen). Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue staining before flow cytometry or cell transfer experiments.

Flow Cytometry

The following antibodies were used for FACS analysis: CD45 (30-F11), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), Ly6G (1A8), F4/80 (BM8), MHCII (AF6-120.1), CD3 (506A2), and IL-17A (TC11-18H10) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; eBioscience, San Diego, CA; or R&D Systems).46 Analyses were performed on a B&D LSRII system using Diva software and were analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Culture of Mouse Kidney Epithelial Tubular Cells and Stimulation

Mouse kidney tubular cells47 were cultured in DMEM with 3% FCS (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) and stimulated with varying concentrations of IL-17A, IL-17F, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, as indicated (all from Pepro Tech, Hamburg, Germany). CXCL5 mRNA expression levels were analyzed after 4 hours of incubation. Protein levels were determined after 8 and 24 hours in the supernatants by specific CXCL5 ELISA (R&D Systems). Antibodies to detect NF-κB p65 (D14E12) and phospho-NFκ-B p65 (93H1) as well as ERK and phospho-ERK (D13.14.4E) in immunoblots were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Laser Microdissection

Microdissection was carried out on mouse kidney tissue using the PALM MicroBeam IP 230V Z microscope.44 Under direct visual control, selected tissue compartments (glomeruli or cortical tubulointerstitium) were dissected. RNA from microdissected tissue was prepared using the PALM RNA extraction kit.

BM Transplantation

Male CXCL5−/− or WT mice aged 5 to 6 weeks received 9.5 Gy total body irradiation. Each recipient mouse (WT or CXCL5−/−) was intravenously injected with 5×106 BM cells (WT or CXCL5−/−) within 6 hours of irradiation.48 The efficiency of BM replacement was assessed using congenic CD45 mouse strains (CD45.1 and CD45.2). After irradiation and transplantation, >90% of circulating leukocytes, >98% of BM leukocytes, and >90% of splenic leukocytes expressed the phenotypic marker of the transplanted BM (n=6; data not shown). NTN was induced 4 weeks after BM transplantation.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Analysis in Human Patients

RNA was isolated with the RNA Micro Kit (Roche) from paraffin-embedded renal specimens of patients with ANCA-associated GN or acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Chemokine expression was analyzed by RT-PCR. Baseline kidney allograft biopsies before transplantation (without significant pathology) served as controls. All samples were run in duplicate and were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA to account for small RNA and cDNA variability. Human analysis was approved by the local ethics committee (PV3162).

Statistical Analyses

Data were expressed as the means±SDs. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS package and GraphPad Prism 5 software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The t test was used for comparison between two groups. In the case of three or more groups, one-way ANOVA was used, followed by a post hoc analysis with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (KFO 228: PA 754/7-2 to U.P. and C.F.K.; MI 476/4-2 to H.-W.M.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013101061/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P: Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 159–175, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eyles JL, Hickey MJ, Norman MU, Croker BA, Roberts AW, Drake SF, James WG, Metcalf D, Campbell IK, Wicks IP: A key role for G-CSF-induced neutrophil production and trafficking during inflammatory arthritis. Blood 112: 5193–5201, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summers SA, Steinmetz OM, Li M, Kausman JY, Semple T, Edgtton KL, Borza DB, Braley H, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR: Th1 and Th17 cells induce proliferative glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2518–2524, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velden J, Paust HJ, Hoxha E, Turner JE, Steinmetz OM, Wolf G, Jabs WJ, Özcan F, Beige J, Heering PJ, Schröder S, Kneißler U, Disteldorf E, Mittrücker HW, Stahl RA, Helmchen U, Panzer U: Renal IL-17 expression in human ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1663–F1673, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallusto F, Baggiolini M: Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nat Immunol 9: 949–952, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O: The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity 36: 705–716, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK: IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 485–517, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fogli LK, Sundrud MS, Goel S, Bajwa S, Jensen K, Derudder E, Sun A, Coffre M, Uyttenhove C, Van Snick J, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rao A, Grunig G, Durbin J, Casola SS, Rajewsky K, Koralov SB: T cell-derived IL-17 mediates epithelial changes in the airway and drives pulmonary neutrophilia. J Immunol 191: 3100–3111, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schall TJ, Proudfoot AE: Overcoming hurdles in developing successful drugs targeting chemokine receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 355–363, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devi S, Li A, Westhorpe CL, Lo CY, Abeynaike LD, Snelgrove SL, Hall P, Ooi JD, Sobey CG, Kitching AR, Hickey MJ: Multiphoton imaging reveals a new leukocyte recruitment paradigm in the glomerulus. Nat Med 19: 107–112, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paust HJ, Turner JE, Riedel JH, Disteldorf E, Peters A, Schmidt T, Krebs C, Velden J, Mittrücker HW, Steinmetz OM, Stahl RA, Panzer U: Chemokines play a critical role in the cross-regulation of Th1 and Th17 immune responses in murine crescentic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 82: 72–83, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odobasic D, Gan PY, Summers SA, Semple TJ, Muljadi RC, Iwakura Y, Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR: Interleukin-17A promotes early but attenuates established disease in crescentic glomerulonephritis in mice. Am J Pathol 179: 1188–1198, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heymann F, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Hamilton-Williams EE, Hammerich L, Panzer U, Kaden S, Quaggin SE, Floege J, Gröne HJ, Kurts C: Kidney dendritic cell activation is required for progression of renal disease in a mouse model of glomerular injury. J Clin Invest 119: 1286–1297, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pickens SR, Chamberlain ND, Volin MV, Gonzalez M, Pope RM, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Kolls JK, Shahrara S: Anti-CXCL5 therapy ameliorates IL-17-induced arthritis by decreasing joint vascularization. Angiogenesis 14: 443–455, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaffen SL: Recent advances in the IL-17 cytokine family. Curr Opin Immunol 23: 613–619, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE: Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol 83: 64–70, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tittel AP, Heuser C, Ohliger C, Knolle PA, Engel DR, Kurts C: Kidney dendritic cells induce innate immunity against bacterial pyelonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1435–1441, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones SA, Sutton CE, Cua D, Mills KH: Therapeutic potential of targeting IL-17. Nat Immunol 13: 1022–1025, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JE, Paust HJ, Steinmetz OM, Panzer U: The Th17 immune response in renal inflammation. Kidney Int 77: 1070–1075, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong X, Bachman LA, Miller MN, Nath KA, Griffin MD: Dendritic cells facilitate accumulation of IL-17 T cells in the kidney following acute renal obstruction. Kidney Int 74: 1294–1309, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR: The emergence of TH17 cells as effectors of renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 235–238, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulone C, Giorgini A, Freeley S, Coughlan A, Robson MG: Transferred antigen-specific T(H)17 but not T(H)1 cells induce crescentic glomerulonephritis in mice. Am J Pathol 179: 2683–2690, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Krueger JG, Kricorian G, Aras G, Li J, Russell CB, Thompson EH, Baumgartner S: Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N Engl J Med 366: 1181–1189, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Gao LL, Blank MA, Johanns J, Guzzo C, Sands BE, Hanauer SB, Targan S, Rutgeerts P, Ghosh S, de Villiers WJ, Panaccione R, Greenberg G, Schreiber S, Lichtiger S, Feagan BG, CERTIFI Study Group : Ustekinumab induction and maintenance therapy in refractory Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 367: 1519–1528, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Lindén A: Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol 162: 2347–2352, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Mei J, Gonzales L, Yang G, Dai N, Wang P, Zhang P, Favara M, Malcolm KC, Guttentag S, Worthen GS: IL-17A and TNF-α exert synergistic effects on expression of CXCL5 by alveolar type II cells in vivo and in vitro. J Immunol 186: 3197–3205, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mei J, Liu Y, Dai N, Favara M, Greene T, Jeyaseelan S, Poncz M, Lee JS, Worthen GS: CXCL5 regulates chemokine scavenging and pulmonary host defense to bacterial infection. Immunity 33: 106–117, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou RC, Kim ND, Sadik CD, Seung E, Lan Y, Byrne MH, Haribabu B, Iwakura Y, Luster AD: Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascade drives neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Immunity 33: 266–278, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald B, Pittman K, Menezes GB, Hirota SA, Slaba I, Waterhouse CC, Beck PL, Muruve DA, Kubes P: Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science 330: 362–366, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paust HJ, Turner JE, Steinmetz OM, Peters A, Heymann F, Hölscher C, Wolf G, Kurts C, Mittrücker HW, Stahl RA, Panzer U: The IL-23/Th17 axis contributes to renal injury in experimental glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 969–979, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Couser WG: Basic and translational concepts of immune-mediated glomerular diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 381–399, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, Rees AJ: The immune system and kidney disease: Basic concepts and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 738–753, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sadik CD, Kim ND, Alekseeva E, Luster AD: IL-17RA signaling amplifies antibody-induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 6: e26342, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisitkun P, Ha HL, Wang H, Claudio E, Tivy CC, Zhou H, Mayadas TN, Illei GG, Siebenlist U: Interleukin-17 cytokines are critical in development of fatal lupus glomerulonephritis. Immunity 37: 1104–1115, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mei J, Liu Y, Dai N, Hoffmann C, Hudock KM, Zhang P, Guttentag SH, Kolls JK, Oliver PM, Bushman FD, Worthen GS: Cxcr2 and Cxcl5 regulate the IL-17/G-CSF axis and neutrophil homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest 122: 974–986, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hang L, Haraoka M, Agace WW, Leffler H, Burdick M, Strieter R, Svanborg C: Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 is required for neutrophil passage across the epithelial barrier of the infected urinary tract. J Immunol 162: 3037–3044, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svensson M, Irjala H, Svanborg C, Godaly G: Effects of epithelial and neutrophil CXCR2 on innate immunity and resistance to kidney infection. Kidney Int 74: 81–90, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svensson M, Yadav M, Holmqvist B, Lutay N, Svanborg C, Godaly G: Acute pyelonephritis and renal scarring are caused by dysfunctional innate immunity in mCxcr2 heterozygous mice. Kidney Int 80: 1064–1072, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frendéus B, Godaly G, Hang L, Karpman D, Lundstedt AC, Svanborg C: Interleukin 8 receptor deficiency confers susceptibility to acute experimental pyelonephritis and may have a human counterpart. J Exp Med 192: 881–890, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gan PY, Steinmetz OM, Tan DS, O’Sullivan KM, Ooi JD, Iwakura Y, Kitching AR, Holdsworth SR: Th17 cells promote autoimmune anti-myeloperoxidase glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 925–931, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Timmeren MM, Heeringa P: Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis: Recent insights from animal models. Curr Opin Rheumatol 24: 8–14, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Veen BS, Petersen AH, Belperio JA, Satchell SC, Mathieson PW, Molema G, Heeringa P: Spatiotemporal expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in experimental anti-myeloperoxidase antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis. Clin Exp Immunol 158: 143–153, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nouailles G, Dorhoi A, Koch M, Zerrahn J, Weiner J, 3rd, Faé KC, Arrey F, Kuhlmann S, Bandermann S, Loewe D, Mollenkopf HJ, Vogelzang A, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Mittrücker HW, McEwen G, Kaufmann SH: CXCL5-secreting pulmonary epithelial cells drive destructive neutrophilic inflammation in tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 124: 1268–1282, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panzer U, Steinmetz OM, Reinking RR, Meyer TN, Fehr S, Schneider A, Zahner G, Wolf G, Helmchen U, Schaerli P, Stahl RA, Thaiss F: Compartment-specific expression and function of the chemokine IP-10/CXCL10 in a model of renal endothelial microvascular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 454–464, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riedel JH, Paust HJ, Turner JE, Tittel AP, Krebs C, Disteldorf E, Wegscheid C, Tiegs G, Velden J, Mittrücker HW, Garbi N, Stahl RA, Steinmetz OM, Kurts C, Panzer U: Immature renal dendritic cells recruit regulatory CXCR6(+) invariant natural killer T cells to attenuate crescentic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1987–2000, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner JE, Krebs C, Tittel AP, Paust HJ, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Bennstein SB, Steinmetz OM, Prinz I, Magnus T, Korn T, Stahl RA, Kurts C, Panzer U: IL-17A production by renal γδ T cells promotes kidney injury in crescentic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1486–1495, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolf G, Mueller E, Stahl RA, Ziyadeh FN: Angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy of cultured murine proximal tubular cells is mediated by endogenous transforming growth factor-beta. J Clin Invest 92: 1366–1372, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kluger MA, Zahner G, Paust HJ, Schaper M, Magnus T, Panzer U, Stahl RA: Leukocyte-derived MMP9 is crucial for the recruitment of proinflammatory macrophages in experimental glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 83: 865–877, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.