Abstract

The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) of the kidney is necessary for extracellular volume homeostasis and normal arterial BP. Activity of ENaC is enhanced by proteolytic cleavage of the γ-subunit and putative release of a 43-amino acid inhibitory tract from the γ-subunit ectodomain. We hypothesized that proteolytic processing of γENaC occurs in the human kidney under physiologic conditions and that proteinuria contributes to aberrant proteolytic activation. Here, we used monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with specificity to the human 43-mer inhibitory tract (N and C termini, mAbinhibit, and mAb4C11) and the neoepitope generated after proteolytic cleavage at the prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site (K181-V182 and mAbprostasin) to examine human nephrectomy specimens. By immunoblotting, kidney cortex homogenate from patients treated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists (n=6) or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n=6) exhibited no significant difference in the amount of full-length or furin-cleaved γENaC or the furin-cleaved–to–full-length ratio of γENaC compared with homogenate from patients on no medication (n=5). Patients treated with diuretics (n=4) displayed higher abundance of full-length and furin-cleaved γENaC, with no significant change in the furin-cleaved–to–full-length γENaC ratio. In patients with proteinuria (n=6), the inhibitory tract was detected only in full-length γENaC by mAbinhibit. Prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved γENaC was detected consistently only in tissue from patients with proteinuria and observed in collecting ducts. In conclusion, human kidney γENaC is subject to proteolytic cleavage, yielding fragments compatible with furin cleavage, and proteinuria is associated with cleavage at the putative prostasin/kallikrein site and removal of the inhibitory tract within γENaC.

Keywords: cell and transport physiology, epithelial sodium channel, kidney, ion channel, proteinuria

The aldosterone-stimulated heteromultimer epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) is expressed predominantly in kidney, colon, sweat glands, and lung.1,2 The critical role of renal ENaC activity is emphasized by the observation that gain-of-function mutations lead to hypertension (Liddle’s syndrome), whereas loss-of-function mutations lead to renal salt-wasting (pseudohypoaldosterism).3,4 ENaC is an established target for antihypertensive treatment with aldosterone receptor antagonists and channel inhibitors (e.g., amiloride and benzamil).

Proteolytic processing of α- and γ-subunits stimulates the activity of ENaC, and this mode of regulation results in larger incremental increase in current compared with changes in channel abundance or agonist stimulation.5–9 Proteolytic processing of the subunit occurs during biosynthesis and maturation and at the apical plasma membrane. The Golgi-residing proprotein convertase furin can cleave the α-subunit two times and the γ-subunit one time during maturation before the channel reaches the plasma membrane.10–13 Membrane-associated ENaC channels that are near-silent can be activated by additional extracellular proteolysis of the γ-subunit.14,15 In the γ-subunit, putative cleavage sites for prostasin,16 kallikrein17 (similar site as prostasin), elastase,18 and plasmin19 exist. Aldosterone stimulation leads to an increased level of proteolytically processed γENaC,20–22 and in rat, prostasin expression is positively regulated by aldosterone.23 Prostasin is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored apical serine protease24 expressed in the collecting duct25–27 that activates γENaC at a site close to but in the C-terminal direction to the furin cleavage with putative release of an 43-residue inhibitory tract.9,14,16,28 We and other groups have shown that, in pathologic conditions with proteinuria, urine contains aberrantly filtered plasmin that activates ENaC current in vitro—either directly or in low concentrations, through prostasin.5,29–31 However, it is not known whether human kidney ENaC is cleaved under physiologic conditions and if the proteolysis is augmented in conditions with proteinuria. In this study, it was hypothesized that human kidney displays physiologic proteolytic processing of γENaC by furin and prostasin/kallikrein, that the degree of proteolysis differs between conditions with expected differences in aldosterone, and that proteolysis is amplified by proteinuria. To address the hypotheses, a retrospective design was applied to examine human kidney tissue from nephrectomy specimens with known presurgery pharmacologic treatment by Western immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and cytochemistry with three murine mAbs directed against selected epitopes within γENaC.

Results

An Antibody Directed against the Inhibitory Peptide Tract Produces Distinct Bands by Immunoblotting of Human Kidney Tissue and Yields Specific Labeling of Human Kidney Sections

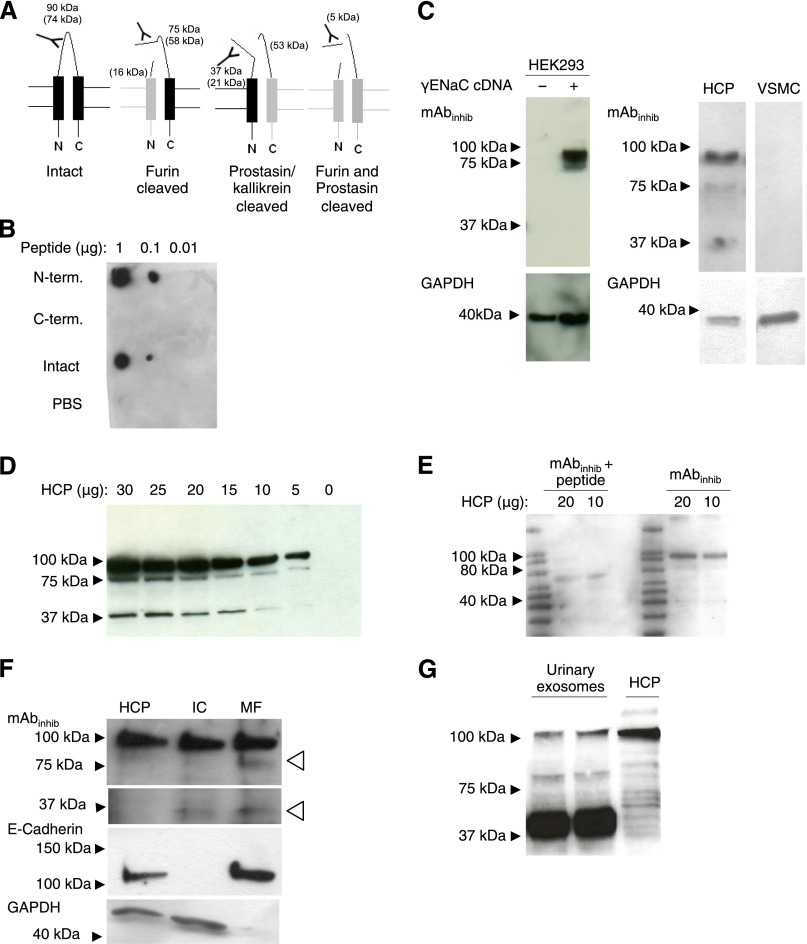

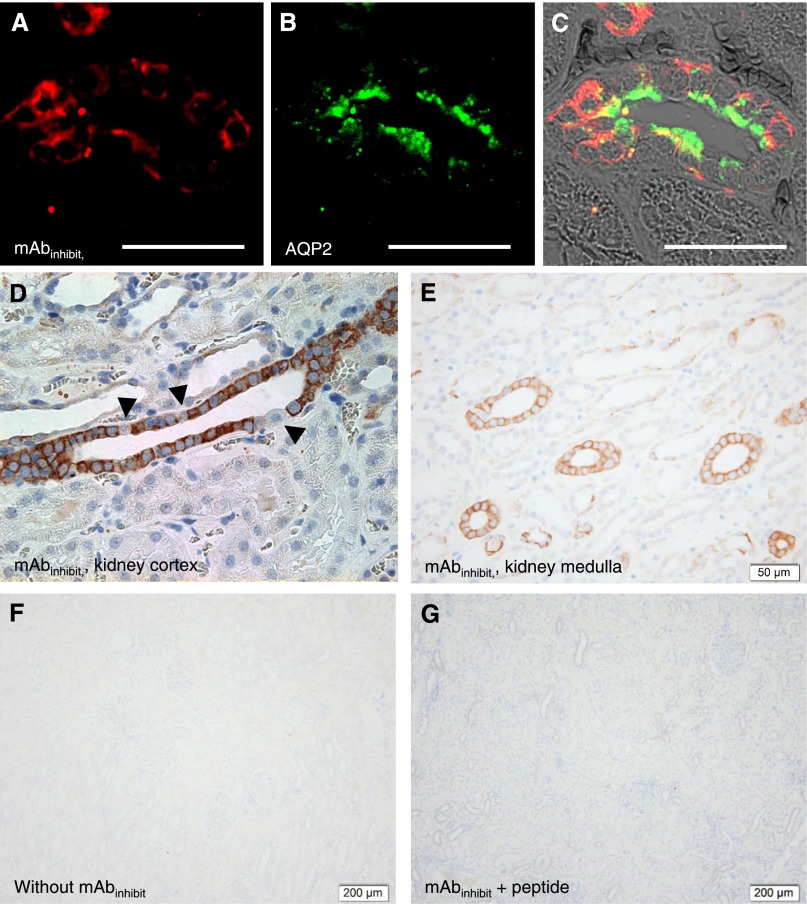

An mAb directed against the inhibitory peptide (mAbinhibit) was generated against the N-terminal one half of the inhibitory tract of human γENaC. The mAbinhibit antibody was designed to recognize full-length, furin-cleaved γENaC and γENaC with a second C-terminal cleavage only by, for example, prostasin (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 1A). The free inhibitory peptide would be below the range of detection (5 kD) with the immunoblotting protocol used in this study. Dot blots showed that mAbinhibit reacted with the peptide corresponding to the full-length and the N-terminal one half of the inhibitory peptide, whereas no reactivity against the C-terminal one half was detected (Figure 1B). Immunoblotting of homogenates from human embryonic kidney-293 (HEK-293) cells transfected with human γENaC cDNA displayed a readily detectable band at approximately 90 kD and a less abundant product at approximately 75 kD, which was not present in mock-transfected HEK-293 cells (Figure 1C). The mAbinhibit did not produce any band in homogenate of human cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), which is in contrast to homogenates of a human kidney cortex pool (HCP) (Figure 1C). Immunoblotting of serially diluted HCP from five patients displayed three distinct bands with molecular sizes corresponding to approximately 90, approximately 75, and approximately 37 kD (Figure 1D). An mAb directed against the C-terminal one half of the inhibitory tract (mAb4C11) recognized only the C-terminal one half of the peptide but mimicked the pattern of mAbinhibit with HCP (Supplemental Figure 1B). The intensities of the three bands decreased proportionally with decreasing amounts of loaded homogenate in the range of 5–20 µg protein (Supplemental Figure 1C). The three bands were abolished by preabsorption of mAbinhibit with the immunogenic peptide (Figure 1E). Subcellular fractioning of HCP into intracellular compartment (IC) and membrane fraction (MF) showed that mAbinhibit reacted with an epitope at approximately 90 kD in the IC and MF (Figure 1F). An approximately 75-kD band appeared only in the MF (Figure 1F, open arrows), whereas an approximately 37-kD band was detectable in the IC and MF. E-cadherin was detected in MF only, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was detected in cytoplasm only (Figure 1F). Using urine exosomes from a healthy control person for mAbinhibit immunoblotting yielded a similar pattern of molecular sizes at approximately 90, 75, and 37 kD as in the HCP but with an opposite pattern of relative abundances (i.e., the 90-kD variant was low in abundance compared with the fragment at 37 kD that was vastly predominant) (Figure 1G). Immunohistochemical and fluorescence labeling of kidney sections produced a signal that was limited to the colleting ducts judged from labeling in confluent cortical tubules and colocalization with aquaporin 2 (AQP2) in serial sections (Supplemental Figure 1E) and double immunofluorescence (Figure 2, A–C). Of note, mAbinhibit signal was associated predominantly with cytoplasm and less conspicuous in apical membranes where AQP2 was abundant (Figure 2C). Labeling signal spared single cells along the cortical collecting ducts and was restricted to principal cells (Figure 2D). In the medulla, labeling was continuously associated with collecting ducts (Figure 2E). In the absence of primary antibody, incubation with secondary antibody yielded no signal (Figure 2F), and incubation of mAbinhibit with surplus of immunizing peptide before addition to the sections prevented the signal (Figure 2G).

Figure 1.

mAbinhibit recognizes intact, furin-cleaved and prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved γENaC by Western immunoblotting. (A) mAbinhibit was generated against an epitope within the N-terminal one half of the putative inhibitory tract in the human γENaC subunit. The proteolytic processing of γENaC theoretically leads to four fragments: intact, furin-cleaved, prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved, and furin- and prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved γENaC. The experimentally measured sizes are indicated as well as the formula molecular mass (in parenthesis). The furin- and prostasin/kallikrein-released fragment has a molecular mass of 5 kD, which is not resolvable by Western blotting in our setup. (B) Dot blot of the N- and C-terminal one half of the inhibitory peptide as well as the full-length inhibitory peptide (Intact) shows that mAbinhibit only displayed immunoreactivity to the N-terminal one half of the full-length inhibitory peptide. PBS was used as a negative control. (C) In HEK-293 cells transfected with human γENaC expression vector, a band at approximately 90 kD and a less abundant product at 75 kD were detected using mAbinhibit, whereas no bands were detected in mock-transfected HEK293 cells. In contrast to the HCP from five patients, no bands were detected in VSMCs. GADPH was used as loading control. (D) Western blotting of a serially diluted pool of five human kidney cortex samples displayed three bands with molecular mass of approximately 90, 75, and 37 kD. (E) The immunoreactivity of the three γENaC fragments was abolished by peptide preabsorption with the immunogenic peptide. (F) Fractioning of the cellular compartments of HCP samples showed that mAbinhibit reacted with an epitope present in the IC and MF. Note the presence of 75- and 37-kD fragments in the MF (open arrows). GAPDH was used as a loading control for the intracellular fraction, whereas E-cadherin was used a loading control for the membrane fraction. (G) Using urine exosomes from a healthy control person for immunoblotting, mAbinhibit yielded molecular sizes at 90, 75, and 37 kD. The intensity of the bands showed an opposite pattern of relative abundances compared with the HCP (i.e., the 90-kD band was low in abundance compared with the fragment at 37 kD that was predominant).

Figure 2.

mAbinhibit Yields specific collecting duct labeling of human kidney sections. (A and C) The fluorescence labeling signal obtained by mAbinhibit was confined to (B) AQP2-expressing cells as seen in (C) the overlay and associated primarily with cytoplasm in human kidney collecting ducts. Scale bar, 50 µm. By immunohistochemistry, mAbinhibit labeling yielded signals from collecting duct in (D) cortical and (E) medullary regions of human kidney tissue sections. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D) Note that mAbinhibit reacts with the majority of cells in the cortical collecting duct (likely principal cells) in human kidneys, whereas it spares single cells, likely intercalated cells (arrows in D). Omission of mAbinhibit and (F) preabsorption with (G) the immunogenic peptide abolished labeling. Scale bar, 200 µm.

An Antibody Directed against the Prostasin/Kallikrein-Specific Cleavage Site in γENaC Recognizes a Distinct Protein

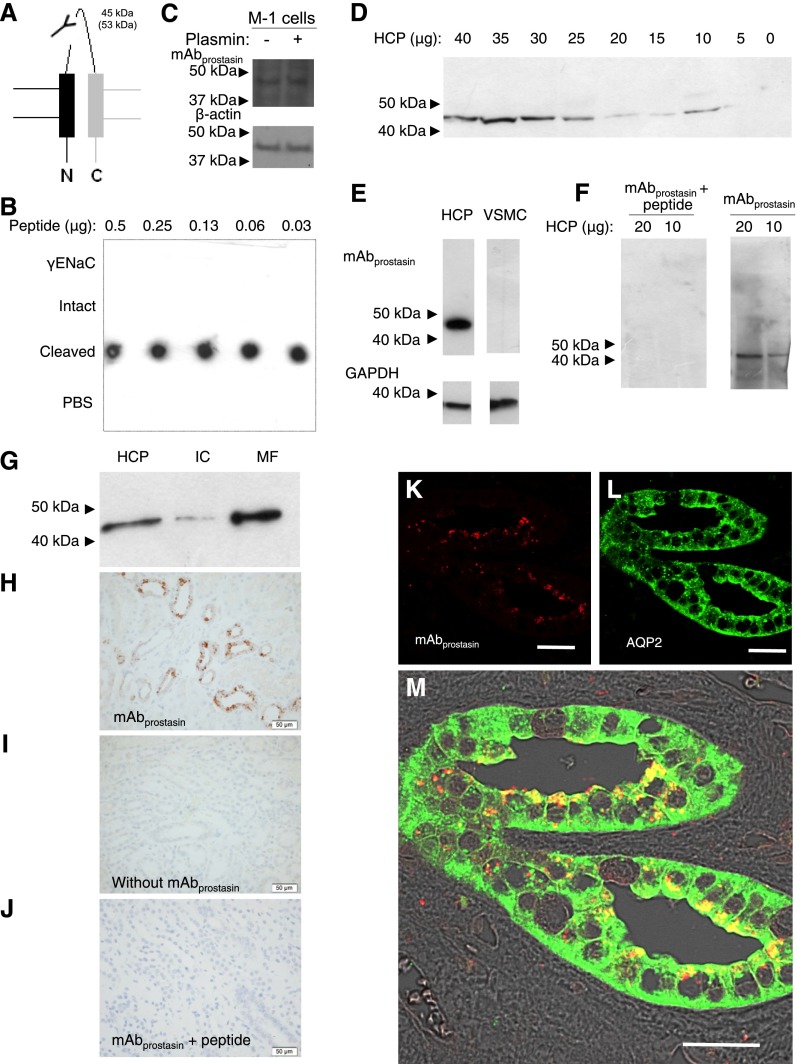

An mAb directed against the prostasin/kallikrein-specific cleavage site (mAbprostasin) was generated against the C-terminal neoepitope exposed after proteolytic cleavage between K181 and V182 common to prostasin and kallikrein in the human γENaC subunit (Figure 3A, Supplemental Figure 1E). Dot blot and ELISA confirmed that mAbprostasin reacted with the immunogenic peptide sequence (Figure 3B, Cleaved, Supplemental Figure 1A) but not with the inhibitory peptide (γENaC) or a peptide spanning the cleavage site (Figure 3B, Intact). Immunoblotting of M-1 cells using mAbprostasin showed a band of approximately 45 kD (Figure 3C). Similarly, immunoblotting of serially diluted HCP detected an approximately 45-kD band (Figure 3D). Two clones showed the same result, and serial dilution of primary antibody resulted in disappearance of Western signal (Supplemental Figure 1, G and H). Equal amounts of protein from VSMC homogenate did not display any immunoreactivity to mAbprostasin compared with HCP, whereas GAPDH was readily detected in both (Figure 3E). Preincubation of mAbprostasin with surplus of immunizing peptide abolished the signal (Figure 3F). Using identical subcellular fractions as shown in Figure 1F, prostasin-cleaved γENaC was associated preferentially with the MF, whereas only a faint band was detected in the IC (Figure 3G). Immunohistochemical labeling of kidney sections with mAbprostasin showed staining of cells in part of the tubular system (Figure 3H), which was not detectable in the absence of primary antibody (Figure 3I) or after preincubation of mAbprostasin with surplus of immunizing peptide (Figure 3J). The signal was at or close to the apical membrane and associated with subapical vesicles and apical membranes (Figure 3, K and M) in cells expressing AQP2 (Figure 3, L and M).

Figure 3.

mAbprostasin Recognizes the neoepitope generated after proteolytic cleavage at the prostasin/kallikrein-site in γENaC. (A) mAbprostasin was directed against the C-terminal neoepitope exposed after proteolytic processing at the putative prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site in the human γENaC subunit. (B) The reactivity of mAbprostasin was tested by dot blot using full-length γENaC inhibitory peptide (γENaC) and peptides spanning the proposed prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site (Intact) or exposing the distal part of the γENaC subunit after proteolytic processing by prostasin/kallikrein (Cleaved). mAbprostasin only reacted with the exposed cleavage site. PBS was used as a negative control. (C) Western blot of M-1 cells showing that the approximately 45-kD band is detected with or without plasmin stimulation. (D) Western blot of a pool of five HCP samples displayed a single band with immunoreactivity to mAbprostasin with a molecular mass of approximately 45 kD. (E) In contrast to the HCP, VSMCs displayed no detectable prostasin-cleaved γENaC. (F) The immunoreactivity was neutralized by peptide preabsorption with the immunogenic peptide. (G) Western blotting after cellular fractioning of HCP showed that mAbprostasin displayed immunoreactivity to an epitope present predominantly in the MF compared with low abundance in the cytoplasmic fraction. (H) Immunohistochemical labeling using mAbprostasin was associated with the collecting duct. (I) Omission of mAbprostasin and (J) preabsorption with the immunogenic peptide abolished labeling. Scale bar, 50 μm. Immunofluorescence double labeling for the prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site with (K and M) mAbprostasin (red) and (L and M) an AQP2-specific antibody (green) showed immunofluorescence signal in the same cell and mAbprostasin-labeled apical membranes and subapical vesicular structures. Scale bar, 30 µm.

Intact and Processed γENaC in Human Kidney Tissue from Patients Who Received Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors

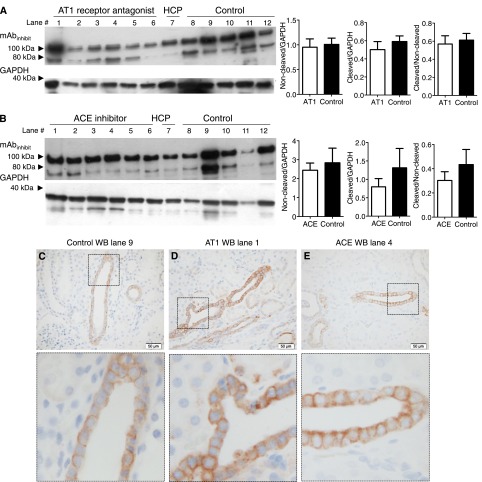

Kidney tissue from patients receiving no medication (n=5), angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor antagonists (n=6), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (n=6) was collected (Supplemental Table 1). There was no significant difference in the amounts of full-length and 75-kD furin-cleaved γENaC as well as the ratio between furin-cleaved and noncleaved γENaC in patients receiving AT1 receptor antagonists (Figure 4A) and ACE inhibitors (Figure 4B) compared with patients taking no preoperative medication (the uncropped Western blot in Supplemental Figure 2, A and B). In tissue sections from patients who received no medication (n=2) and AT1 receptor-blocked (n=2) and ACE inhibitor-treated patients (n=2), immunostaining was readily detectable in collecting ducts in cortex (Figure 4, C–E) and medulla (Supplemental Figure 2, E–G).

Figure 4.

Treatment with angiotensin II AT1 receptor blocker (AT1) and ACE inhibition in human patients does not significantly alter the proteolytic processing of the γENaC subunit. (A) Western blot of kidney cortex from patients receiving AT1 receptor antagonists (n=6) and control patients (n=5) displayed no significant difference between the GAPDH-normalized densities of the full-length (90-kD band) and cleaved (75-kD band) γENaC. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 2A. (B) Western blot of kidney cortex from patients receiving ACE inhibitors (n=6) compared with control patients (n=5). No significant differences were detected between the densities of the full-length (90-kD band), cleaved (75-kD band), and cleaved-to-noncleaved ratio of γENaC. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 2B. The HCP from five patients used for validation was included in each blot. (C, upper panel) Immunohistochemical staining of kidney sections from control patients yielded readily detectable labeling in the collecting ducts. (C, lower panel) Magnification of the area covered by the square in C, upper panel. The kidney section corresponds to lane 9 in A. A similar labeling was seen in kidney sections from patients treated with (D) AT1 receptor antagonist and (E) ACE inhibitors. The kidney section corresponds to (D) lane 1 in A and (E) lane 4 in B. HCP, human kidney cortex pool. Scale bar, 50 µm.

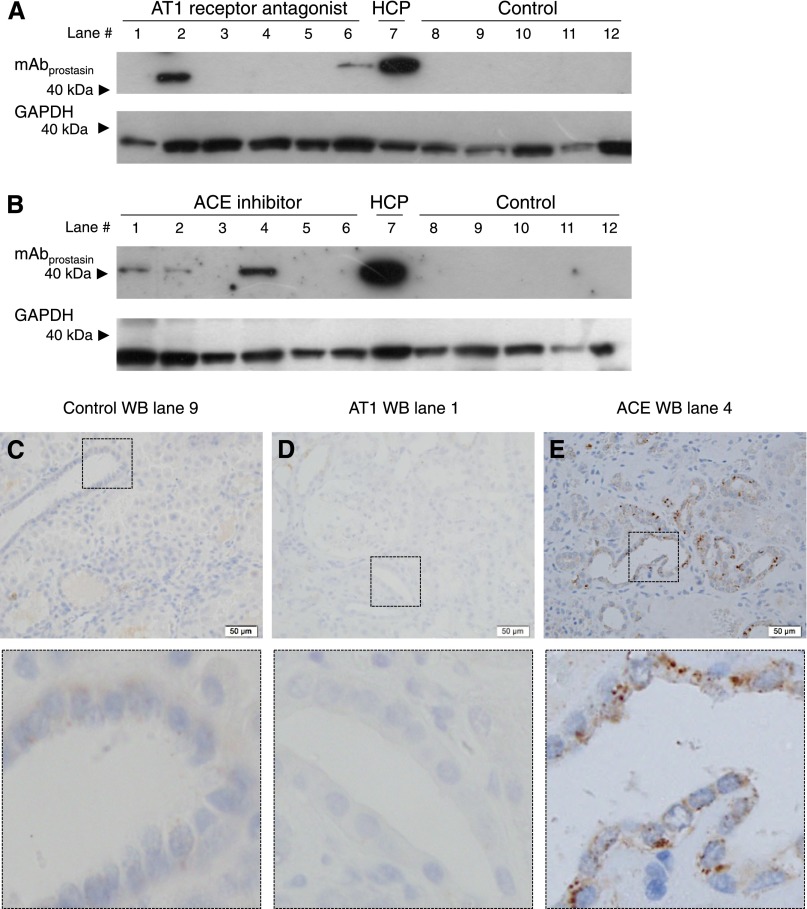

Using mAbprostasin, immunoblotting analysis detected a band in the HCP (Figure 5, A and B), whereas no band was detectable in samples from the no medication group, even after prolonged exposure times (Figure 5, A and B, the uncropped Western blot in Supplemental Figure 2, C and D). GAPDH was readily detectable and at similar levels in five patients who received no medication (Figure 5, A and B). In kidney homogenate from patients receiving AT1 receptor antagonist, immunoblotting with mAbprostasin yielded an immunoreactive band in two of six patients (Figure 5A), and three of six patients receiving ACE inhibitor treatment were positive (Figure 5B), whereas GAPDH was present in equal amounts in all samples. Immunohistochemical labeling of kidney sections displayed no distinct mAbprostasin signal in the cortical region in control and AT1 receptor antagonist-treated patients (Figure 5, C and D). Staining was detected in the kidney cortex in the ACE inhibitor-treated patient (lane 4) who was positive by immunoblotting (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Treatment with AT1 receptor antagonists and ACE inhibitors is not consistently associated with higher levels of prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved γENaC. (A and B) No bands are detected in Western blots made from kidney cortex from the control patients, whereas (A) two of six AT1 receptor antagonist-treated patients (lanes 2 and 6) and (B) three of six ACE inhibitor-treated patients (lanes 1, 2, and 4) displayed γENaC cleavage at the putative prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 2, C and D. mAbprostasin labeling was not detectable in the cortical region of human kidneys from (C) control (corresponding to lane 9 in A) and (D) AT1 receptor antagonist-treated patients (corresponding to lane 1 in A), whereas (E) labeling was present in kidney sections from a patient receiving ACE inhibitors (corresponding to lane 4 in B). The areas covered by the squares in the upper panels of C–E are magnified in the lower panels of C–E. HCP, human kidney cortex pool. Scale bar, 50µm.

Intact and Processed γENaC in Human Kidney Tissue from Patients Treated with Diuretics and Patients with Proteinuria

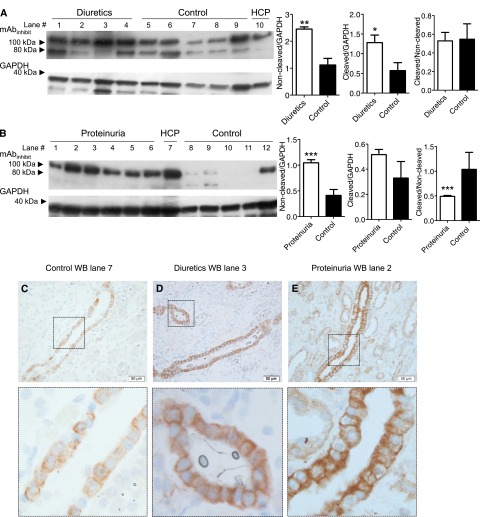

Kidney tissue from patients who received diuretics only (n=4) or displayed proteinuria (n=6) was collected (Supplemental Table 1). In patients treated with diuretics, a significantly higher abundance of full-length and furin-cleaved γENaC protein was apparent compared with controls (Figure 6A, uncropped Western blot in Supplemental Figure 3A). There was no significant difference in GAPDH levels (Figure 6A). There was no significant difference in the ratios between furin-cleaved and noncleaved γENaC (Figure 6A). Patients with proteinuria displayed significantly higher levels of full-length γENaC abundance normalized for GAPDH abundance compared with controls (Figure 6B). No difference in furin-cleaved γENaC abundance was detected compared with control patients (Figure 6B, uncropped Western blot and longer exposure time in Supplemental Figure 3B). There was, thus, a significantly lower ratio between furin-cleaved and intact full-length γENaC protein in proteinuric patients (Figure 6B). In kidney sections from controls, patients treated with diuretics, and patients displaying proteinuria, the mAbinhibit yielded intracellular labeling signal readily detectable in collecting ducts in the cortical (Figure 6, C–E) and medullary regions (Supplemental Figure 3, E and F).

Figure 6.

Higher levels of γENaC in kidney tissue from patients treated with diuretics and patients with proteinuria. (A) Western immunoblotting for the inhibitory peptide with kidney homogenate from patients receiving diuretics (n=4) and patients who did not receive medication (control; n=5). Patients treated with diuretics displayed a significantly higher protein level of full-length (90-kD band) and cleaved (75-kD band) γENaC, whereas no significant difference was detected between the cleaved and noncleaved ratios. Exposure time: 30 seconds. *P<0.05; **P<0.01. GAPDH was used as an internal loading and housekeeping control. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 3A. (B) Western blotting on kidney cortex homogenate from patients with proteinuria (n=6) and control patients (n=5). Proteinuric patients displayed a significantly higher level of full-length (90-kD band) γENaC, whereas no significant difference was detected in the level of cleaved (75-kD band; faint signal) γENaC. The ratio between noncleaved and cleaved was significantly reduced in proteinuric patients compared with controls. Exposure time: 5 seconds. ***P<0.001. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 3B as well as a blot with a 1-minute exposure time. The HCP was a positive control. (C–E) In kidney sections from control, patient treated with diuretics, and patient with proteinuria, respectively, the mAbinhibit labeling was present in the collecting duct cells. The lower panels in C–E show magnifications of selected tubular segments. HCP, human kidney cortex pool. Scale bar, 50 µm.

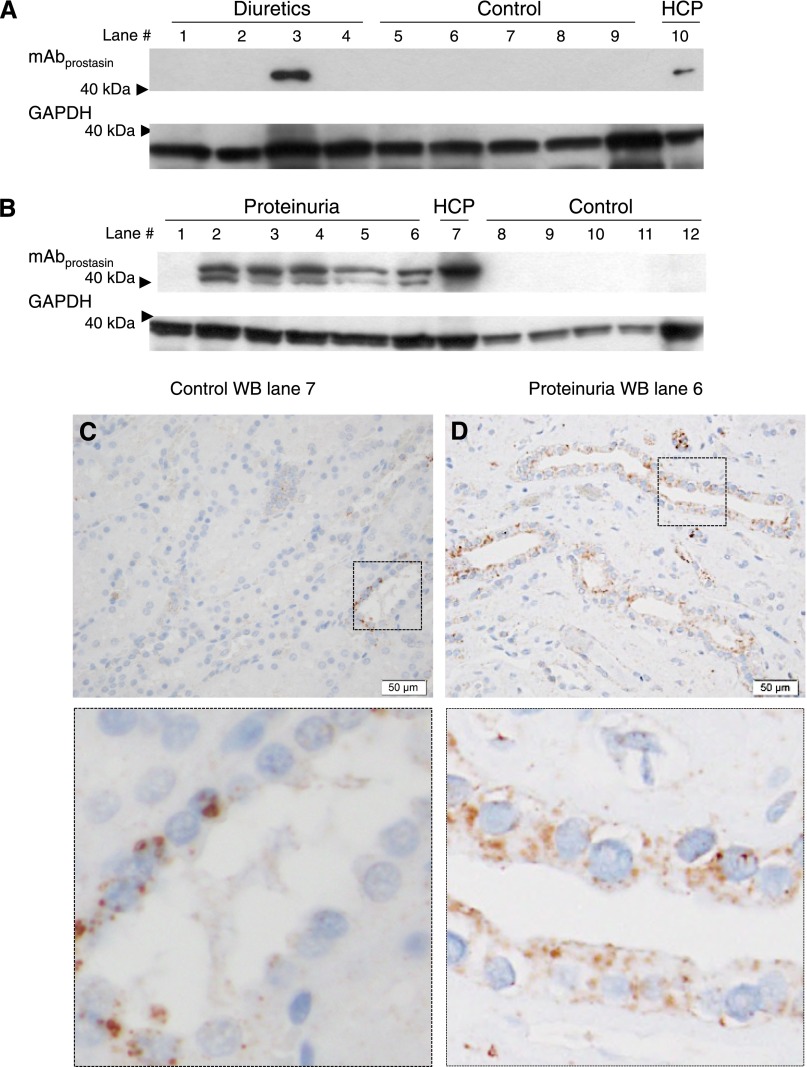

In immunoblots of cortical kidney samples from patients treated with diuretics, one of four patients yielded an mAbprostasin immunoreactive band, whereas GAPDH was equally present between the two groups (Figure 7A, uncropped Western blot in Supplemental Figure 3C). This patient showed labeling of the collecting ducts cells (not shown). Kidney homogenates from patients with proteinuria showed a significant double band with mAbprostasin in five of six patients (Figure 7B, uncropped Western blot in Supplemental Figure 3D). Kidney sections from patients with proteinuria showed distinct punctual labeling associated with collecting duct apical membranes in the cortex (Figure 7D) and medulla (Supplemental Figure 3H) in contrast to sections from a control (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Proteinuria is associated with higher levels of prostasin/kallikrein-cleaved γENaC and positive immunolabeling. (A and B) Result of immunoblotting experiments with kidney cortex homogenate from (A) patients treated with diuretics, (B) patients who displayed proteinuria, and (A and B) patients who received no medication (control). (A) No bands were detected in Western blots made from control patients, whereas (B) one of four patients treated with diuretics (lane 3) and (B) five of six proteinuric patients (lanes 2–6) displayed immunoreactivity with the prostasin cleavage site-specific antibody. (B) Note that the mAbprostasin band is present as a double band in homogenate from proteinuric patients. The uncropped Western blot is shown in Supplemental Figure 3, C and D. (C) Immunohistochemical staining detected a few cells with immunoreactive protein in kidney sections from controls (corresponding to lane 7 in A). (D) In a patient displaying proteinuria, immunohistochemical staining showed labeling in the collecting duct cells (corresponding to lane 6 in B). HCP, human kidney cortex pool. Scale bar, 50 µm.

Discussion

This study examined γENaC proteolysis variants in human kidney tissue, and data were consistent with physiologic proteolytic processing of γENaC by furin and proteinuria-dependent second-hit processing by prostasin/kallikrein. Moreover, abundance of full-length γENaC protein was higher in kidney tissue from patients who received diuretics, consistent with many observations from experimental animals.

On the basis of a number of observations, the applied mAbs were accepted to be specific. mAbinhibit detected full-length human γENaC in a heterologous expression system with predicted size. In kidney cortex homogenates, mAbinhibit and mAb4C11 directed against the N and C termini of the inhibitory tract yielded similar bands. Immunohistochemical and fluorescence labeling of kidney sections showed that mAbinhibit-labeled cells were positive for AQP2, consistent with the localization of ENaC.20 Dot blots showed that the antibodies mAbinhibit, mAb4C11, and mAbprostasin reacted with the immunogenic peptide and not related peptides. Peptide preabsorption prevented signal in both Western immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry. Nonepithelial cell homogenate (VSMCs) showed no Western signal, and subcellular fractioning of cortical homogenate yielded predicted compartmental association.

Western immunoblotting for γENaC in the kidney homogenate pool with mAbinhibit (and mAb4C11) revealed three distinct bands. The approximately 90–95- and approximately 75-kD bands were compatible with previously published molecular sizes of intact, full-length γENaC protein and the C-terminal fragment of γENaC after proteolytical processing by furin, respectively.10,12,20,23 The mAbinhibit was directed against an epitope that resides in the inhibitory tract, and putative two-hit cleavage distal to the furin cleavage site would remove the epitope. In case of proteolysis by a distally acting protease only (e.g., prostasin or kallikrein), a third fragment containing the N terminus of γENaC would be observed with mAbinhibit. The observed N-terminal product at approximately 37 kD has a lower electrophoretic mobility than would be predicted on the basis of the amino acid sequence of this fragment (i.e., 21 kD). An origin as cleavage product was supported by an inverse abundance pattern between homogenate and urine exosomes, with predominance of the full-length form in the homogenate and vice versa in exosome fraction. Because two hit-processed γENaC would not be detected by mAbinhibit, an antibody directed against the putative prostasin/kallikrein site, mAbprostasin, was generated. A priori, this antibody should detect a protein with a predicted size of 53 kD spanning the region from the prostasin cleavage site to the C-terminal end. In the HCP, mAbprostasin reacted with a protein with an estimated molecular mass of approximately 45 kD. The reason for the discrepancy is not known but could potentially be because of an additional proteolytic cleavage by proteases, such as channel-activating protease 2, that induces cleavage near the second transmembrane domain in γENaC.32 However, addition of the molecular mass of this C-terminal fragment to the putative N-terminal fragment detected by mAbinhibit adds up to 82 kD, which matches the full length rather precisely.

Patients who received AT1 receptor antagonists and ACE inhibitors would be predicted to have suppressed aldosterone. There was no difference in full-length and furin-cleaved γENaC abundance compared with patients with no medication. Because aldosterone was not measured and patients did not receive medication at the day of surgery, it could be because of unchanged aldosterone levels in these patients. Thus, it cannot be excluded from these data that aldosterone affects γENaC cleavage in humans. In patients treated with diuretics only, there was a higher abundance of full-length and furin-cleaved γENaC in kidney tissue compared with patients who received no medication. By inference, this result is consistent with but does not show regulation of γENaC level by extracellular volume contraction/aldosterone.21

In rats, the majority of collecting duct γENaC at the apical plasma membrane is cleaved in low-salt intake conditions and after aldosterone infusion,20,21,23 and the shift is inhibited by a serine protease/prostasin inhibitor.23 The mAbinhibit antibody would not detect two-hit cleaved γENaC directly. Cleavage at, for example, the putative prostasin cleavage site would lead to release of the epitope, which would be detected indirectly as a reduction in the level of the furin-cleaved fragment. We did not detect changes in abundance of full-length versus furin-cleaved isoforms of γENaC, indicating that furin cleavage of γENaC is constitutive and that physiologic prostasin/kallikrein cleavage of γENaC is not the predominant means of regulating ENaC activity in human kidneys.

Expression and urinary excretion of prostasin is regulated by aldosterone in rat.33 Urinary prostasin levels have been suggested as a candidate marker for ENaC activation in humans.34 However, mAbprostasin detected the cleavage epitope only in a minority of human kidney cortex samples from patients who received no drugs, AT1 receptor antagonists, ACE inhibitors, or diuretics. This observation supports only a minor role for prostasin/kallikrein cleavage during physiologic conditions in humans.

Prostasin-cleaved γENaC was detected consistently only in patients with proteinuria. The mAbinhibit revealed an increased level of full-length intact γENaC in proteinuric patients, whereas cleaved fragments with the inhibitory tract epitope contained were hardly detectable. The significantly reduced ratio between furin-cleaved and noncleaved γENaC is consistent with the dual cleavage of γENaC in proteinuric patients, leading to putative release of the inhibitory peptide and detection of intact moiety in whole tissue. This finding is also in accordance with proteinuric animal models that are characterized by a shift in molecular mass of the γENaC.35,36 We have previously shown that protein-rich urines from adult and pediatric nephrotic patients and rats5,29 as well as patients with preeclampsia30 contain the serine protease plasmin, which cleaves γENaC and activates ENaC current.5,19,29,30 Plasmin-induced cleavage and activation of ENaC are dependent on cell surface expression of prostasin in the mouse cortical collecting duct cell line M-1.29 Because the prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site would be absent if plasmin cleavage occurred, these data strongly suggest that, during proteinuria in humans, proteolytic activation of γENaC converges on prostasin/kallikrein.

This study is limited by the retrospective, cross-sectional design. Noninvasive human studies are needed to assess whether γENaC cleavage is affected by plasma aldosterone level and in diseases with proteinuria. An attractive way of determining the proteolytic cleavage status of γENaC noninvasively is by urinary exosomes, which are vesicles retracted and later released from the apical membrane.37 In vitro data show that changes in cellular levels of AQP2 are reflected in the exosomes.38 Thus, the exosome data indicate that it is mainly proteolytically processed ENaCs that are excreted in the urine.

This study suggests that human renal γENaC is proteolytically modified and that a higher abundance of γENaC protein is present in patients treated with diuretics. Proteinuria is associated with proteolytical cleavage at the prostasin/kallikrein cleavage site and loss of the inhibitory tract from γENaC. The results of this study are consistent with our previous studies5,30,31 and support the concept that proteinuria induces cleavage and activation of ENaC. Urinary protease activity could be an attractive pharmacologic target to counter excessive sodium retention in the collecting ducts.

Concise Methods

Production and Cloning of mAbs

Three mAbs (mAbinhibit, mAb4C11, and mAbprostasin) directed against the inhibitory tract and the putative prostasin cleavage site within the human γENaC were generated (Figures 1A and 3A). The mAbinhibit was as described previously.29 mAb4C11 was developed using the synthetic peptide (CLIFDQDEKGKARDFFTGRKRK) corresponding to amino acids 161–181 of the human γENaC subunit. The antibody against the prostasin-cleaved human γENaC (GenBank accession no. NM_001039) was developed using the synthetic peptide (VGGSIIHKAC) corresponding to amino acid residues 182–190. The peptides were synthesized (EzBiolab, Carmel, IN) with an extra cysteine residue to facilitate conjugation to diphtheria toxin. Production and cloning are described in Supplemental Material.

Human Kidney Tissue and Patient Data

Human kidney tissue samples were obtained from patients undergoing nephrectomy at the Department of Urology, Odense University Hospital. The patients fasted 6 hours before the operation. The only medication that was continued on the day of surgery was low-dose heparin and for diabetic patients, insulin; 45–60 minutes after removal of the kidney, tissue was separated into cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. All patients gave informed written consent to the use of tissue for research purpose. The use of the tissue was approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethical Committee (approval no. 20010035). The patient characteristics are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Preparation of Urinary Exosomes

Collection of urine for exosome analysis was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Region of Southern Denmark (approval no. 20110146). Spot urine sample (100 ml) from a healthy 22-year-old woman was collected, immediately supplemented with two complete miniature tablets (Roche), and stored overnight at 4°C. The sample was thoroughly vortexed and subsequently centrifuged at 1363×g at 4°C for 30 minutes. Exosomes were pelleted by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant at 220,000×g for 100 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 100 µl resuspension buffer (0.3 M sucrose, 25 mM imidazole, 1 mM EDTA-disodium salt [pH 7.2], and complete miniature tablet [Roche]). The resuspended pellet was used immediately for Western blotting as described below.

Subcellular Fractioning

For subcellular fractionation, the Qproteome Cell Compartment Kit (QIAGEN) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Five human kidney cortex samples were cut into three to four pieces, washed with PBS, and lysed (Lysis Buffer with Protease Inhibitor; QIAGEN). The samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant, containing the cytosolic fraction, was stored. The pellet was resuspended in Extractions Buffer (Buffer CE2; QIAGEN) and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C on an end-over-end shaker. Then, the suspension was centrifuged at 6000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant, containing the membrane fraction, was transferred and stored.

Immunohistochemistry

The kidney samples were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for a maximum of 24 hours and embedded in paraffin. The blocks were cut in 1- to 4-µm sections, dewaxed, and rehydrated through a series of Tissue-Tec–Tissue-Clear (Sakura ProHosp) and ethanol baths (99%–70%). Antigen retrieval was performed in Target Retrieval Solution (Dako) at 60°C overnight (for mAbinhibit) or 80°C for 2 hours (for mAbprostasin). When staining with mAbinhibit, the sections were washed two times for 5 minutes and one time for 15 minutes in 0.05% Tween 20/Tris-buffered saline (TBST; 20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.6) and then, blocked in 3% BSA in TBST (all from Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were incubated with mAbinhibit (1:500) in 1.5% BSA in TBST overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (polyclonal goat anti-mouse, P0447; Dako) diluted 1:1000 in TBST followed by extensive washing. For the prostasin cleavage-specific mAb, the CSA II Biotinfree Tyramide Signal Amplification System (Dako) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HRP localization was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine+substrate (K3468; Dako), and the slides were counterstained with Mayer Hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Pictures were taken with an Olympus BX51 microscope mounted with a DP26 camera using Olympus cellSens software.

Western Immunoblotting Analyses

Human kidney cortex was homogenized in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 1% Triton-X 100, complete protease inhibitor; Roche Diagnostic) on ice for 30 minutes. The tissues were further homogenized (Polyton PT 3100) and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000×g. Supernatant was collected for further use. After vortexing, the lysates were centrifuged for 1 minute at 13,000×g. Supernatants were mixed with 10× reducing agent (NuPAGE; Bio-Rad) and 4× LDS Sample Buffer (NuPAGE; Bio-Rad) and heat-denatured at 95°C. The samples were loaded on a 4%–15% Tris-HCl SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad). Precision Plus Protein Standard (Bio-Rad) or MagicMark XP Western Protein Standard (Invitrogen) was used as the size marker. Subsequently, the samples were blotted onto a poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membrane (pore size is 0.45 µm, Immobilon-P; EMD Millipore). The membranes were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich) to verify equal blotting.

Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in tris-buffered saline/Tween 20. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated either 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After washing, the primary antibodies were detected with HRP-coupled goat anti-mouse antibodies (P0447; Dako) diluted 1:2000 in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. The membranes were washed, and antibody binding was detected using the ECL System (Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare) before exposure to x-ray film (Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare). For reprobing, membranes were striped two times for 5 minutes each with TBST (pH 2) before blocking. GAPDH was used as loading control (1:4000, ab9485; Abcam, Inc.). The film was scanned in grayscale with resolution set on 600 ppi. The quantification was done using Quantity One analysis software (4.6.3; Bio-Rad).

Dot Blot

Dot blot was performed to test the specificity of the mAbs. PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; EMD Millipore) were activated in 99.99% ethanol for 15 seconds, washed in demineralized water, and placed in TBST. TBST was poured away, and the peptide of interest was slowly applied onto the PVDF membrane (2 µL each sample). Different concentrations of the peptide were used. The membrane was allowed to dry and blocked 1 hour in 5% milk in TBST. Primary mAb was added, and the procedure was finished as for normal Western blot as described above.

Overexpression of γENaC in HEK293 Cells

HEK293 cells were grown in DMEM:F12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen) and Pen/Strep (Invitrogen) at 5% CO2 and 37°C. HEK293 cells were transfected with human γENaC cDNA (catalog no. RC209264; OriGene Technologies) using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested and lysed 48 hours after transfection and subjected to Western immunoblotting as described above.

Plasmin Stimulation of M-1 Cells

M-1 cells were stimulated as previously described.29 Briefly, M-1 cells were grown in 12-well plates for 2 days. Cells were washed one time in HBSS (Gibco) and stimulated with or without human plasmin (5 µg/ml; Innovative Research) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Cells were lysed and processed for Western blotting as described above.

Confocal Laser-Scanning Microscopy

Human kidney sections were processed as described above and probed with mAbinhibit and goat anti-AQP2 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed extensively in TBST and subsequently incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with AlexaFluor488 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen) and AlexaFluor555 donkey anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). The sections were then washed with TBST, mounted, and imaged using an Olympus FV1000 confocal laser-scanning microscopy as previously described.29

Statistical Analyses

Results are expressed as means±SEMs; n corresponds to the number of subjects. Differences between groups were evaluated with the t test, and normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A P value<0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lars Vitved, Lis Teusch, Inger Nissen, Kenneth Andersen, Mie Rytz Hansen, and Susanne Hansen for skillful technical assistance.

This study was supported by grants from the Danish Strategic Research Council and the Danish Research Council for Health and Disease and by the Lundbeck Foundation, the AP Moller Foundation, and the Region of Southern Denmark. The bioimaging experiments reported here were performed at Danish Molecular Biomedical Imaging Center (DaMBIC), a bioimaging research core facility at the University of Southern Denmark. DaMBIC was established by an equipment grant from the Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation and internal funding from the University of Southern Denmark.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Cutting It Out: ENaC Processing in the Human Nephron,” on pages 1–3.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013111173/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Canessa CM, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC: Epithelial sodium channel related to proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Nature 361: 467–470, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC: Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature 367: 463–467, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimkets RA, Warnock DG, Bositis CM, Nelson-Williams C, Hansson JH, Schambelan M, Gill JR, Jr., Ulick S, Milora RV, Findling JW, Canessa CM, Rossier BC, Lifton RP: Liddle’s syndrome: Heritable human hypertension caused by mutations in the beta subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. Cell 79: 407–414, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossier BC, Pradervand S, Schild L, Hummler E: Epithelial sodium channel and the control of sodium balance: Interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Annu Rev Physiol 64: 877–897, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svenningsen P, Bistrup C, Friis UG, Bertog M, Haerteis S, Krueger B, Stubbe J, Jensen ON, Thiesson HC, Uhrenholt TR, Jespersen B, Jensen BL, Korbmacher C, Skøtt O: Plasmin in nephrotic urine activates the epithelial sodium channel. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 299–310, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleyman TR, Carattino MD, Hughey RP: ENaC at the cutting edge: Regulation of epithelial sodium channels by proteases. J Biol Chem 284: 20447–20451, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planes C, Randrianarison NH, Charles RP, Frateschi S, Cluzeaud F, Vuagniaux G, Soler P, Clerici C, Rossier BC, Hummler E: ENaC-mediated alveolar fluid clearance and lung fluid balance depend on the channel-activating protease 1. EMBO Mol Med 2: 26–37, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruan YC, Guo JH, Liu X, Zhang R, Tsang LL, Dong JD, Chen H, Yu MK, Jiang X, Zhang XH, Fok KL, Chung YW, Huang H, Zhou WL, Chan HC: Activation of the epithelial Na+ channel triggers prostaglandin E₂ release and production required for embryo implantation. Nat Med 18: 1112–1117, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallet V, Chraibi A, Gaeggeler HP, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC: An epithelial serine protease activates the amiloride-sensitive sodium channel. Nature 389: 607–610, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughey RP, Bruns JB, Kinlough CL, Kleyman TR: Distinct pools of epithelial sodium channels are expressed at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 279: 48491–48494, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughey RP, Mueller GM, Bruns JB, Kinlough CL, Poland PA, Harkleroad KL, Carattino MD, Kleyman TR: Maturation of the epithelial Na+ channel involves proteolytic processing of the alpha- and gamma-subunits. J Biol Chem 278: 37073–37082, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughey RP, Bruns JB, Kinlough CL, Harkleroad KL, Tong Q, Carattino MD, Johnson JP, Stockand JD, Kleyman TR: Epithelial sodium channels are activated by furin-dependent proteolysis. J Biol Chem 279: 18111–18114, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris M, Garcia-Caballero A, Stutts MJ, Firsov D, Rossier BC: Preferential assembly of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunits in Xenopus oocytes: Role of furin-mediated endogenous proteolysis. J Biol Chem 283: 7455–7463, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caldwell RA, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ: Serine protease activation of near-silent epithelial Na+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C190–C194, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caldwell RA, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ: Neutrophil elastase activates near-silent epithelial Na+ channels and increases airway epithelial Na+ transport. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L813–L819, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruns JB, Carattino MD, Sheng S, Maarouf AB, Weisz OA, Pilewski JM, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR: Epithelial Na+ channels are fully activated by furin- and prostasin-dependent release of an inhibitory peptide from the gamma-subunit. J Biol Chem 282: 6153–6160, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel AB, Chao J, Palmer LG: Tissue kallikrein activation of the epithelial Na channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F540–F550, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adebamiro A, Cheng Y, Rao US, Danahay H, Bridges RJ: A segment of gamma ENaC mediates elastase activation of Na+ transport. J Gen Physiol 130: 611–629, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Passero CJ, Mueller GM, Rondon-Berrios H, Tofovic SP, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR: Plasmin activates epithelial Na+ channels by cleaving the gamma subunit. J Biol Chem 283: 36586–36591, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masilamani S, Kim GH, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA: Aldosterone-mediated regulation of ENaC alpha, beta, and gamma subunit proteins in rat kidney. J Clin Invest 104: R19–R23, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frindt G, Ergonul Z, Palmer LG: Surface expression of epithelial Na channel protein in rat kidney. J Gen Physiol 131: 617–627, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ergonul Z, Frindt G, Palmer LG: Regulation of maturation and processing of ENaC subunits in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F683–F693, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uchimura K, Kakizoe Y, Onoue T, Hayata M, Morinaga J, Yamazoe R, Ueda M, Mizumoto T, Adachi M, Miyoshi T, Shiraishi N, Sakai Y, Tomita K, Kitamura K: In vivo contribution of serine proteases to the proteolytic activation of γENaC in aldosterone-infused rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F939–F943, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu JX, Chao L, Chao J: Prostasin is a novel human serine proteinase from seminal fluid. Purification, tissue distribution, and localization in prostate gland. J Biol Chem 269: 18843–18848, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steensgaard M, Svenningsen P, Tinning AR, Nielsen TD, Jørgensen F, Kjaersgaard G, Madsen K, Jensen BL: Apical serine protease activity is necessary for assembly of a high-resistance renal collecting duct epithelium. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 200: 347–359, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adachi M, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, Narikiyo T, Iwashita K, Shiraishi N, Nonoguchi H, Tomita K: Activation of epithelial sodium channels by prostasin in Xenopus oocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1114–1121, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuagniaux G, Vallet V, Jaeger NF, Pfister C, Bens M, Farman N, Courtois-Coutry N, Vandewalle A, Rossier BC, Hummler E: Activation of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel by the serine protease mCAP1 expressed in a mouse cortical collecting duct cell line. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 828–834, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passero CJ, Carattino MD, Kashlan OB, Myerburg MM, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR: Defining an inhibitory domain in the gamma subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F854–F861, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svenningsen P, Uhrenholt TR, Palarasah Y, Skjødt K, Jensen BL, Skøtt O: Prostasin-dependent activation of epithelial Na+ channels by low plasmin concentrations. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1733–R1741, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buhl KB, Friis UG, Svenningsen P, Gulaveerasingam A, Ovesen P, Frederiksen-Møller B, Jespersen B, Bistrup C, Jensen BL: Urinary plasmin activates collecting duct ENaC current in preeclampsia. Hypertension 60: 1346–1351, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen RF, Buhl KB, Jensen BL, Svenningsen P, Friis UG, Jespersen B, Rittig S: Remission of nephrotic syndrome diminishes urinary plasmin content and abolishes activation of ENaC. Pediatr Nephrol 28: 1227–1234, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Caballero A, Dang Y, He H, Stutts MJ: ENaC proteolytic regulation by channel-activating protease 2. J Gen Physiol 132: 521–535, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narikiyo T, Kitamura K, Adachi M, Miyoshi T, Iwashita K, Shiraishi N, Nonoguchi H, Chen LM, Chai KX, Chao J, Tomita K: Regulation of prostasin by aldosterone in the kidney. J Clin Invest 109: 401–408, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olivieri O, Castagna A, Guarini P, Chiecchi L, Sabaini G, Pizzolo F, Corrocher R, Righetti PG: Urinary prostasin: A candidate marker of epithelial sodium channel activation in humans. Hypertension 46: 683–688, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bou Matar RN, Malik B, Wang XH, Martin CF, Eaton DC, Sands JM, Klein JD: Protein abundance of urea transporters and aquaporin 2 change differently in nephrotic pair-fed vs. non-pair-fed rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1545–F1553, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Seigneux S, Kim SW, Hemmingsen SC, Frøkiaer J, Nielsen S: Increased expression but not targeting of ENaC in adrenalectomized rats with PAN-induced nephrotic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F208–F217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA: Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 13368–13373, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Street JM, Birkhoff W, Menzies RI, Webb DJ, Bailey MA, Dear JW: Exosomal transmission of functional aquaporin 2 in kidney cortical collecting duct cells. J Physiol 589: 6119–6127, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.