Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the most common cause of ESRD in the United States. Podocyte injury is an important feature of DKD that is likely to be caused by circulating factors other than glucose. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is a circulating factor found to be elevated in the serum of patients with FSGS and causes podocyte αVβ3 integrin-dependent migration in vitro. Furthermore, αVβ3 integrin activation occurs in association with decreased podocyte-specific expression of acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b (SMPDL3b) in kidney biopsy specimens from patients with FSGS. However, whether suPAR-dependent αVβ3 integrin activation occurs in diseases other than FSGS and whether there is a direct link between circulating suPAR levels and SMPDL3b expression in podocytes remain to be established. Our data indicate that serum suPAR levels are also elevated in patients with DKD. However, unlike in FSGS, SMPDL3b expression was increased in glomeruli from patients with DKD and DKD sera-treated human podocytes, where it prevented αVβ3 integrin activation by its interaction with suPAR and led to increased RhoA activity, rendering podocytes more susceptible to apoptosis. In vivo, inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase reduced proteinuria in experimental DKD but not FSGS, indicating that SMPDL3b expression levels determined the podocyte injury phenotype. These observations suggest that SMPDL3b may be an important modulator of podocyte function by shifting suPAR-mediated podocyte injury from a migratory phenotype to an apoptotic phenotype and that it represents a novel therapeutic glomerular disease target.

Keywords: podocyte, FSGS, diabetic nephropathy, proteinuria, glomerular disease

The pathogenesis of FSGS and diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is associated with podocyte injury.1–5 Acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase 3b (SMPDL3b) is a protein with homology to acid sphingomyelinase (ASMase), and it is involved in the sphingomyelin (SM) catabolic processes. SMPDL3b exists in two isoforms and is mainly localized in the lipid rafts of podocytes.6,7 We reported that decreased SMPDL3b expression is associated with actin cytoskeleton remodeling in podocytes, rendering them more susceptible to injury in recurrent FSGS.7 In addition, circulating factors are thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of podocyte injury in both FSGS8–11 and DKD.12–16 In sera of patients with FSGS, increased levels of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) were described.11 While increased suPAR levels are associated with other conditions, such as diabetes,17 cardiovascular diseases,18 inflammation,19 and different types of cancers,20 additional investigations are needed to establish the value of suPAR as a disease-specific biomarker.19,21–23 In FSGS, suPAR was found to cause lipid-dependent activation of αVβ3 integrin in podocytes,11,24 but whether this activation occurs in glomerular diseases other than FSGS remains to be established. Furthermore, a link between suPAR and SMPDL3b has not been established.

We hypothesized that suPAR and SMPDL3b functionally interact, and we investigated their respective roles in FSGS and DKD.

Results

Differential Expression of SMPDL3b in FSGS and DKD Protects Podocytes from Injury

Microarray data obtained by glomerular transcriptome analysis of kidney biopsies from patients with FSGS and DKD indicate that SMPDL3b mRNA expression shows a trend to be decreased in patients with FSGS but is significantly increased in patients with DKD (Figure 1A). SMPDL3b protein expression was significantly decreased in podocytes cultured in the presence of high-risk FSGS patient sera (Concise Methods) compared with podocytes cultured in the presence of DKD patient sera or normal human sera (NHS) and upregulated in podocytes cultured in the presence of DKD patient sera compared with podocytes cultured in the presence of NHS (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

SMPDL3b expression in FSGS and DKD. (A) Transcriptional analysis of glomerular SMPDL3b expression in 70 patients with DKD and 18 patients with FSGS compared with 32 living donors. Glomerular SMPDL3b mRNA expression is significantly increased in diabetic glomeruli compared with normal controls but showing a trend to be decreased in glomeruli from FSGS patients compared with controls. Numbers reflect fold change in disease compared with living donors. *q<0.05. (B) SMPDL3b protein expression is significantly decreased in podocytes treated with high-risk FSGS patient sera (*P<0.05) and increased in podocytes treated with DKD+ sera (*P<0.05) compared with podocytes treated with the sera from healthy controls (NHS). SMPDL3b protein expression is also significantly increased in podocytes treated with DKD+ sera compared with podocytes treated with high-risk FSGS patient sera (#P<0.05). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (C) Immunofluorescence staining using phalloidin (red) indicates a loss of stress fibers in podocytes treated with high-risk FSGS sera. SMPDL3b OE podocytes are protected from high-risk FSGS sera-induced actin cytoskeleton rearrangement. (D) Treatment of podocytes with DKD+ sera induces cell blebbing in normal but not in SMPDL3b KD podocytes. (E) Apoptosis in DKD− and DKD+ sera-treated podocytes is significantly increased compared with podocytes treated with NHS. SMPDL3b KD podocytes are protected from DKD+ sera-induced podocyte apoptosis (**P<0.01).

We previously described that podocytes exposed to sera of high-risk FSGS or DKD patients show disease-specific morphologic changes of the actin cytoskeleton7,15 (i.e., a disruption of stress fibers and cell blebbing, respectively). Interestingly, increased expression of SMPDL3b protected podocytes from high-risk FSGS sera-induced cytoskeletal changes (Figure 1C), whereas decreased expression of SMPDL3b protected podocytes from DKD sera-induced cytoskeletal remodeling (Figure 1D). Because podocyte apoptosis is a pathophysiological characteristic observed in DKD,2 we analyzed caspase-3 activity. Caspase-3 activity was significantly increased in DKD patient sera (DKD+)-treated podocytes and in podocytes cultured in the presence of sera from diabetic patients (DKD−) when compared to podocytes cultured in the presence of sera from healthy controls (NHS). DKD+ sera-induced apoptosis was abrogated in SMPDL3b knockdown (SMPDL3b KD) podocytes (Figure 1E).

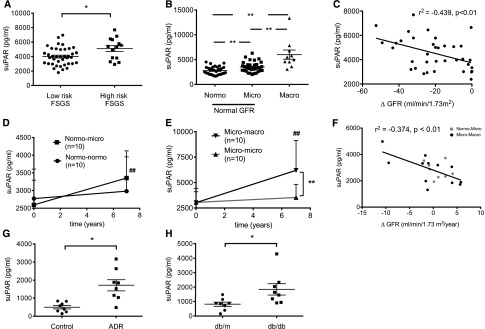

Circulating suPAR Levels Are Elevated in Sera from Patients with FSGS and DKD and Experimental Models of FSGS and DKD

Circulating suPAR levels are increased in a majority of patients with FSGS (primarily those patients at risk for FSGS recurrence after transplantation).25 We measured suPAR levels in the sera of the patients with DKD and compared them with the levels of patients with FSGS. We found elevated suPAR levels in high-risk FSGS patients compared with low-risk FSGS patients (Figure 2A) and high but comparable suPAR levels in patients with microalbuminuric or macroalbuminuric DKD compared with patients with normoalbuminuria and diabetes (Figure 2B, Table 1). In high-risk FSGS patients, suPAR levels were similar and significantly correlated with the decline in GFR within 1 year of follow-up (Figure 2C). In patients with diabetes, suPAR levels significantly increased in patients who progressed from normo- to microalbuminuria (Figure 2D) and patients who progressed from micro- to macroalbuminuria (Figure 2E) but not in patients who remained normo- or microalbuminuric in a 7-year longitudinal study (Figure 2, D and E). Of note, the DKD patients with elevated suPAR levels at baseline analysis had also normal GFR (Table 1, Figure 2B). Furthermore, suPAR levels significantly correlated with the yearly change in GFR (Figure 2F). In experimental animal models, suPAR levels were also significantly elevated in both the adriamycin-induced (ADR) FSGS-like nephropathy model (Figure 2G) and diabetic db/db mice (Figure 2H) compared with their respective controls.

Figure 2.

Serum suPAR in patients with and mouse models of FSGS and DKD. (A) Serum suPAR levels in 14 high-risk FSGS patients are significantly higher compared with low-risk FSGS patients (*P<0.05). (B) Serum suPAR levels are significantly increased in 34 microalbuminuric and 10 macroalbuminuric DKD patients compared with 30 patients with diabetes but normoalbuminuria (**P<0.01). Serum suPAR levels are further significantly increased in 10 macroalbuminuric compared with 34 microalbuminuric DKD patients (**P<0.01). (C) Serum suPAR levels significantly correlate with the renal disease progression in patients enrolled in the FSGS clinical trial cohort (P<0.01). (D) Longitudinal analysis in patients with diabetes showing that suPAR levels at baseline are not significantly different in the nonprogression group (normo-normo) compared with the progression group (normo-micro) but are significantly elevated in the progression group 7 years later (##P<0.01). (E) Longitudinal analysis in patients with diabetes shows that suPAR levels at baseline are not significantly different in the nonprogression group (micro-micro) compared with the progression group (micro-macro) but are significantly elevated in the progression group 7 years later (##P<0.01) and significantly increased compared with the nonprogression group (**P<0.01). (F) Serum suPAR levels significantly correlate with the renal disease progression in diabetic patients (P<0.01). (G and H) suPAR levels in a mouse model of FSGS (ADR-induced nephropathy) and a mouse model of DKD (db/db mice) are significantly increased compared with their respective controls (*P<0.05 ADR versus control; *P<0.05 db/db versus db/m).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with type 1 diabetes at baseline

| Characteristics | Normal AER | Normal AER | Microalbuminuria | Microalbuminuria |

| Sex (m/f) | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/6 |

| Age (yr) | 37±8 | 34±11 | 40±7 | 34±13 |

| Age at onset (yr) | 19±9 | 17±12 | 14±11 | 13±8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9±2.5 | 24.7±4.4 | 27.0±5.4 | 25.3±3.9 |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | 76 [70–81] | 80 [72–93] | 85 [69–94] | 84 [54–106] |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2)a | 99 [91–103] | 95 [82–108] | 92 [79–105] | 101 [61–117] |

| DKD progression | (−) | (+) | (−) | (+) |

| Follow-up time (yr) | 5.6±1.6 | 6.0±1.3 | 5.9±1.4 | 6.1±2.3 |

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. Median [interquartile range]. AER, albumin excretion rate; m, male; f, female.

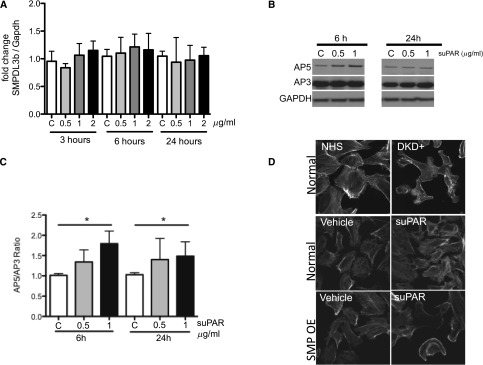

suPAR Does Not Modulate SMPDL3b Expression Levels but Modulates β3 Integrin Activation in Cultured Human Podocytes

To determine if SMPDL3b expression is regulated by suPAR, we treated normal human podocytes with 0.5, 1, and 2 μg/ml suPAR (R&D Systems) for 3, 6, and 24 hours and determined SMPDL3b expression by quantitative real-time PCR. No significant change in SMPDL3b expression levels was observed (Figure 3A), indicating that the physiologic form of suPAR does not regulate SMPDL3b mRNA expression in podocytes. However, SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions followed by Western blot analysis using activated β3 integrin (AP5) and total β3 integrin (AP3) antibodies showed that β3 integrin activation was significantly induced in normal human podocytes treated with suPAR in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 3, B and C).

Figure 3.

In vitro effects of suPAR treatment of human podocytes on SMPDL3b expression levels and β3 integrin activation. (A) Treatment of human podocytes with different concentrations of suPAR (0, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg/ml) for different time spans (3, 6, and 24 hours) indicates that suPAR concentrations and time of exposure to suPAR do not change SMPDL3b mRNA expression levels. (B) Western blot analysis followed by (C) quantitative analysis of normal human podocytes treated with different concentrations of suPAR (0, 0.5, and 1 μg/ml) for 6 and 24 hours reveal significant β3 integrin activation at 24 hours of treatment (*P<0.05). AP5 antibody was used to detect activated β3 integrin and AP3 antibody was used to detect total β3 integrin. (D) Normal human podocytes treated with the sera from patients with DKD (top panel) show a characteristic cytoskeletal remodeling phenotype in the form of cell blebbing. The same cytoskeletal phenotype was observed when SMPDL3b OE podocytes were treated with suPAR (bottom panel) but not when human podocytes expressing endogenous levels of SMPDL3b (middle panel) were exposed to suPAR. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

We previously reported that human podocytes that are cultured in the presence of sera from patients with DKD experience actin cytoskeleton remodeling in the form of cell blebbing (Figure 3D, top panel).15 To test if suPAR treatment of human podocytes is sufficient to induce the same phenotype, we treated normal and SMPDL3b overexpressing (SMPDL3b OE) podocytes with 1 μg/ml suPAR for 24 hours. As expected, suPAR treatment of normal human podocytes did not cause cytoskeleton remodeling in the form of cell blebbing. However, suPAR treatment of SMPDL3b OE podocytes led to cytoskeletal remodeling in the form of cell blebbing, indicating that increased SMPDL3b expression is necessary to cause an suPAR-mediated DKD-like phenotype in human podocytes (Figure 3D).

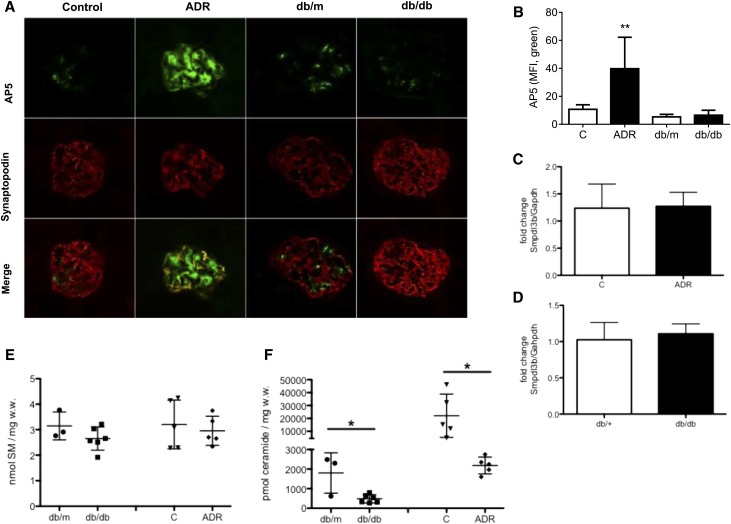

β3 Integrin Is Activated in ADR-Induced Nephropathy but Not db/db Mice

It was previously reported that suPAR can activate β3 integrin in rodent FSGS.11,26 We, therefore, investigated β3 integrin activation in glomeruli of ADR-treated and db/db mice. Fluorescence intensity of glomerular AP5 (a mAb against the activation-dependent conformation of β3 integrin) staining was significantly increased in glomeruli of ADR-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated controls. In contrast, no changes were observed in the glomeruli of db/db mice compared with db/m mice (Figure 4, A and B), indicating that suPAR-mediated activation of β3 integrin is blocked in this DKD model.

Figure 4.

Analysis of mouse models for FSGS and DKD. (A) Immunofluorescence staining with AP5 to detect activated β3 integrin (green) and synaptopodin (red) of glomeruli from db/db and ADR-treated mice. Original Magnification, ×40. (B) Bar graph analysis showing a significant increase of AP5 staining in podocytes and mesangial cells after treatment of the mice with ADR (**P<0.01) compared with vehicle-treated control mice. However, AP5 staining intensity does not change in db/db mice compared with db/m mice. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (C and D) Real-time PCR analysis reveals that Smpdl3b mRNA levels in total kidney cortex are not changed in (C) db/db and (D) ADR-treated mice compared with their respective controls. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (E) Analysis of the SM content in kidney cortexes shows no differences in db/db and ADR-treated mice compared with their respective controls. w.w., wet weight. (F) Analysis of the ceramide content of kidney cortexes shows significantly decreased ceramide levels in db/db and ADR-treated mice compared with their respective controls. *P<0.05.

Decreased Ceramide Levels and Unchanged SMPDL3b Expression Occur in Kidney Cortexes from ADR-Treated or db/db Mice

We analyzed Smpdl3b expression by quantitative real-time PCR in RNA isolated from kidney cortexes of ADR-treated and db/db mice. Smpdl3b mRNA expression in kidney cortex was not significantly changed in ADR-treated (Figure 4C) or db/db mice (Figure 4D) compared with their respective controls. We analyzed the SM and ceramide lipid content in kidney cortexes of ADR-treated and db/db mice. We were not able to detect any difference in the SM content in kidney cortexes of ADR-treated or db/db mice compared with their respective controls (Figure 4E). However, ceramide content quantification revealed significant decreases in ceramide in kidney cortexes of both db/db and ADR-treated mice compared with their respective controls (Figure 4F).

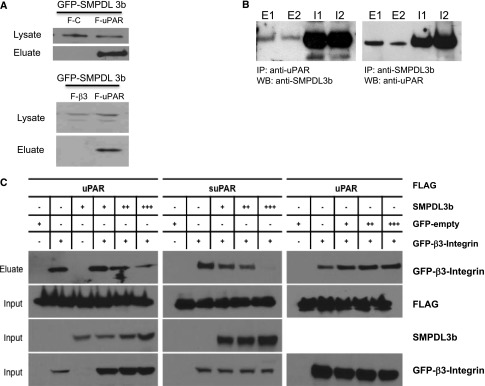

SMPDL3b Interferes with the suPAR/Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor and β3 Integrin Interaction

Because SMPDL3b expression levels are conversely regulated in FSGS and DKD but suPAR serum levels are elevated in both diseases, we hypothesized that SMPDL3b may play a role in suPAR-mediated β3 integrin activation in podocytes. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments performed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells revealed an interaction between SMPDL3b and suPAR but not between SMPDL3b and β3 integrin (Figure 5A). This interaction between suPAR and SMPDL3b was further confirmed by endogenous immunoprecipitation using isolated glomeruli from C57Bl/6 mice injected with PBS or LPS (Figure 5B). Competitive Co-IP experiments using increasing amounts of GFP-SMPDL3b showed that SMPDL3b physically interacts with suPAR/urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) but not with β3 integrin. More importantly, SMPDL3b binding to suPAR/uPAR interfered with suPAR/uPAR and β3 integrin interaction in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Interaction of suPAR and SMPDL3b. (A) Co-IP experiments performed in HEK293 cells showing an interaction between GFP-SMPDL3b and FLAG-uPAR (F-uPAR; upper panel) but not between GFP-SMPDL3b and FLAG-β3 integrin (F-β3; lower panel). FLAG-empty vector (F-C) was used as a negative control (upper panel). (B) Endogenous immunoprecipitation showing interaction of SMPDL3b and suPAR in glomeruli isolated from mice injected with PBS or LPS. E1, eluate from PBS-injected mice; E2, eluate from LPS-injected mice; I1, input (glomerular lysate) from PBS-injected mice; I2, input (glomerular lysate) from LPS-injected mice; IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. (C) Competitive Co-IP experiments performed in HEK293 show that increasing amounts of GFP-SMPDL3b interfere with the interaction of FLAG-uPAR/suPAR and GFP-β3 integrin. However, transfection of GFP-empty vector used as a control does not affect the interaction between uPAR/suPAR and β3 integrin. GFP, green fluorescent protein.

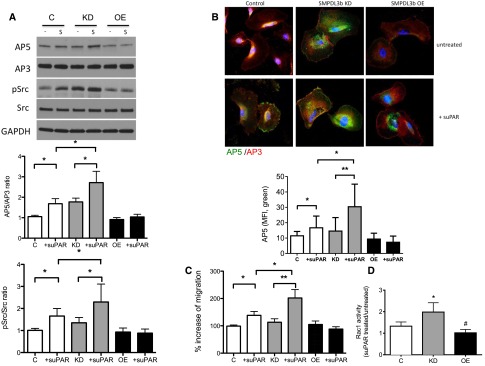

SMPDL3b Regulates suPAR-Mediated Activation of β3 Integrin and Downstream Signaling in Podocytes

To further assess the effect of differential SMPDL3b expression on β3 integrin activation and dependent signaling, we performed Western blot analysis using antibodies to detect AP5 and a downstream integrin effector, Src. Treatment of normal human podocytes with suPAR significantly increased β3 integrin activation as assessed by Western blot analysis (Figures 3, B and C and 6A) and immunofluorescence staining (Figure 6B). However, increased SMPDL3b expression (SMPDL3b OE) protected from suPAR-mediated β3 integrin activation (Figure 6, A and B), whereas decreased expression of SMPDL3b (SMPDL3b KD) rendered podocytes more susceptible to suPAR-mediated β3 integrin activation (Figure 6, A and B). Because the focal adhesion kinase/Src complex acts as a suppressor of RhoA activity downstream of intregrin signaling, thus favoring integrin-mediated migration,27 we determined phospho-Src levels in suPAR-treated human podocytes. As expected, the phospho-Src/Src ratio was significantly increased in suPAR-treated normal podocytes and SMPDL3b KD podocytes but remained unchanged in suPAR-treated SMPDL3b OE podocytes (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Decreased SMPDL3b expression is associated with β3 integrin activation, resulting in a migratory FSGS-like phenotype in podocytes. (A) Human podocytes were incubated for 24 hours with or without suPAR (1 μg/ml). suPAR treatment (S) significantly increased AP5 and phospho-Src protein expression in podocytes, and these changes are more prominent in suPAR-treated human SMPDL3b KD podocytes compared with control podocytes. However, human SMPDL3b OE podocytes are protected from suPAR-induced increases in AP5 (activated β3 integrin) and Src expression (*P<0.05). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) Immunofluorescence staining using antibodies for AP5 (green) and AP3 (red) reveals that human SMPDL3b KD podocytes are characterized by activation of β3 integrin at baseline compared with normal podocytes. Furthermore, although β3 integrin can be activated by suPAR in control podocytes, human SMPDL3b OE podocytes are protected from suPAR-induced β3 integrin activation (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (C) Migration assay showing that suPAR-induced cell migration is significantly increased in control human podocytes and even more accentuated in human SMPDL3b KD podocytes (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). However, suPAR does not increase migration in human SMPDL3b OE podocytes. (D) Rac1 activity is significantly increased in suPAR-treated human SMPDL3b KD podocytes compared with control podocytes and SMPDL3b OE podocytes (*P<0.05, control versus SMPDL3b KD podocytes; #P<0.05, control versus SMPDL3b OE podocytes).

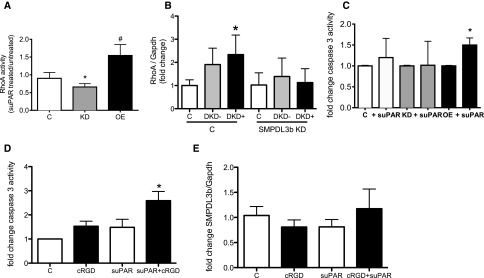

SMPDL3b Regulates suPAR-Mediated Podocyte Migration and Apoptosis

Using transwell migration assays, we showed that suPAR-induced cell migration is more prominent in SMPDL3b KD podocytes compared with normal human podocytes, whereas SMPDL3b OE podocytes are protected from suPAR-induced cell migration (Figure 6C). Because small guanosine 5′-triphophatases are associated with podocyte motility24 and pathogenesis of DKD,28 we analyzed Rac1 (Figure 6D) and RhoA (Figure 7A) activity in suPAR-treated podocytes with differential expression of SMPDL3b. Rac1 activity was significantly higher in suPAR-treated SMPDL3b KD podocytes compared with normal podocytes, whereas SMPDL3b OE podocytes were protected from suPAR-induced Rac1 activation (Figure 6D).

Figure 7.

Increased SMPDL3b expression is associated with the suppression of β3 integrin, resulting in an apoptotic DKD-like phenotype in podocytes. (A) RhoA activity is significantly increased in human SMPDL3b OE podocytes and decreased in SMPDL3b KD podocytes compared with control podocytes (*P<0.05, control versus SMPDL3b KD podocytes; #P<0.05, control versus SMPDL3b OE podocytes). (B) Treatment of normal human podocytes with sera from patients with DKD leads to increased RhoA expression, and SMPDL3b KD podocytes are protected from DKD sera-induced increases in RhoA expression (*P<0.01). (C) suPAR treatment significantly increase apoptosis in SMPDL3b OE podocytes, whereas control and SMPDL3b KD podocytes are not susceptible to suPAR-induced apoptosis (*P<0.01). (D and E) Inhibition of β3 integrin signaling renders (D) normal human podocytes susceptible to suPAR-induced apoptosis, whereas (E) SMPDL3b mRNA expression levels remain unchanged (*P<0.05). cRGD, cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

In contrast, RhoA was activated in SMPDL3b OE but not SMPDL3b KD podocytes (Figure 7A), and SMPDL3b KD podocytes were protected from DKD sera-induced increases in RhoA expression (Figure 7B). These findings suggest that SMPDL3b binding to suPAR leads to differential activation of small guanosine 5′-triphophatases and that a Rac1-dependent migratory phenotype may occur in FSGS, whereas a more stationary and RhoA-dependent phenotype may occur in DKD. Because podocytopenia is a feature of both FSGS and DKD and may result from either excessive migration or apoptosis, we also investigated how the differential expression of SMPDL3b in FSGS and DKD affects podocyte susceptibility to apoptosis. We found that suPAR significantly increased caspase-3 activity in SMPDL3b OE podocytes, whereas SMPDL3b KD podocytes are protected from suPAR-induced apoptosis (Figure 7C). Because increased SMPDL3b expression prevented β3 integrin activation, we investigated whether inhibition of β3 integrin signaling in the presence of suPAR would also be sufficient to induce apoptosis. Interestingly, normal human podocytes simultaneously treated with suPAR and an αVβ3 integrin inhibitor (cyclo RGD) were characterized by significantly increased apoptosis (Figure 7D). This activation occurred in the absence of SMPDL3b mRNA modulation (Figure 7E) and further shows that inactive αVβ3 integrin is necessary to promote suPAR-mediated apoptosis, similar to what we observed in suPAR-treated SMPDL3b OE podocytes.

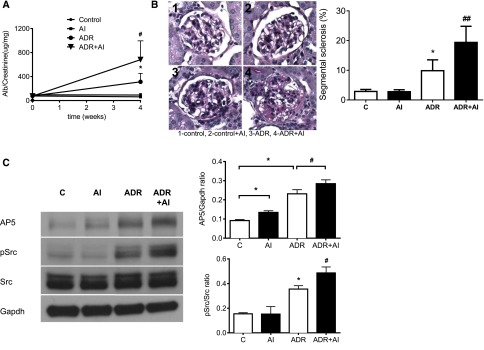

ASMase Inhibitor Aggravates Podocyte Injury in ADR-Induced Nephropathy but Protects from Podocyte Injury in db/db Mice

We previously showed that decreased SMPDL3b expression occurs in parallel with decreased ASMase activity in podocytes treated with sera from patients with recurrent FSGS.7 On the basis of our in vitro observations, we hypothesized that treatment with an ASMase inhibitor would worsen the glomerular phenotype of mice with an FSGS-like podocyte injury, whereas mice with a DKD-like phenotype would be protected from podocyte injury.

As expected, ASMase inhibitor treatment of mice with ADR-induced nephropathy worsened proteinuria (Figure 8A), increased segmental sclerosis (Figure 8B), and increased glomerular β3 integrin and Src activation (Figure 8C) compared with ADR alone.

Figure 8.

ASMase inhibitors (AIs) worsen the phenotype in a mouse model for FSGS. (A) Urine albumin (Alb)-to-creatinine ratio is significantly higher in ADR mice compared with control mice, and AI treatment significantly increases proteinuria in ADR mice (*P<0.05, ADR versus control; #P<0.05, ADR versus ADR+AI). (B) Segmental sclerosis assessed by periodic acid–Schiff staining is significantly worse in ADR mice than control mice (*P<0.05), and the extent of segmental sclerosis is further significantly increased by AI treatment (##P<0.01). (C) Glomerular AP5 (activated β3 integrin) and phospho-Src protein expressions are significantly higher in ADR mice, and these changes are markedly increased after AI treatment (*P<0.05; #P<0.05). cRGD, cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

On the contrary, a 3-month treatment of db/db mice with the same ASMase inhibitor showed a significant reduction of proteinuria compared with untreated mice (Figure 9A). This was associated with a preservation of the glomerular surface area in treated db/db mice that was comparable with that in db/+ mice (Figure 9B). Increased apoptosis (Figure 9C), as shown by increased caspase-3 activation, and RhoA activation (Figure 9D), as shown by immunostaining, were detected in db/db mice compared with control mice or ASMase inhibitor-treated mice.

Figure 9.

ASMase inhibitors (AIs) ameliorate the phenotype in a mouse model for DKD. (A) Urine albumin (Alb)-to-creatinine ratio is significantly higher in db/db mice compared with db/m mice (**P<0.01), and AI treatment significantly abrogates proteinuria in db/db mice compared with untreated db/db mice (#P<0.05). (B) Glomerular surface area is increased in db/db mice compared with db/m mice (*P<0.05); however, glomerular surface area is significantly smaller in ASMase-treated db/db mice compared with untreated db/db mice (#P<0.05) and seems to not be significantly changed compared with db/m mice. (C) Glomerular cleaved caspase-3 expression is significantly higher in db/db mice compared with db/m mice (*P<0.05), and expression is significantly reduced by AI treatment (#P<0.05). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (D) Glomerular active RhoA expression is increased in db/db mice (**P<0.01) and attenuated by AI treatment (#P<0.05). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

Our study provides three novel findings. First, podocyte SMPDL3b levels are contrasted in FSGS (low) versus DKD (high); second, serum suPAR levels are similarly elevated in FSGS and DKD, and third, increased SMPDL3b expression shifts suPAR-mediated podocyte injury from a migratory to an apoptotic phenotype.

We recently described that decreased SMPDL3b expression occurs in glomeruli from patients with recurrent FSGS.7 Using microarray analysis, we showed that SMPDL3b expression is increased in glomeruli from patients with DKD and decreased (although not significantly) in a cohort of patients with FSGS and variable degrees of progression to ESRD. In addition, we showed that FSGS sera-treated podocytes exhibit decreased SMPDL3b expression, increased cortical actin, and loss of stress fibers, whereas DKD sera-treated podocytes show increased SMPDL3b expression associated with actin reorganization in cell blebs (Figure 1).

Increased and similar suPAR levels were detected in the sera from patients with FSGS and DKD and correlate with the yearly change in GFR. Increased levels of suPAR were also observed in mouse models of FSGS and DKD (Figure 2). Because SMPDL3b levels were differentially regulated, whereas suPAR levels were similarly elevated in patients with FSGS and DKD, we hypothesized that SMPDL3b is an important regulator of suPAR-induced activation of αVβ3 integrin signaling in podocytes.

SM is a critical component of the plasma membrane and abundant in lipid rafts.6 Because SMPDL3b is a protein with homology to ASMase, it may activate SM metabolic pathways, leading to the redistribution of SM and cholesterol from the lipid raft domains to intracellular compartments. Such concomitant loss of SM and cholesterol is often observed during apoptosis and may be associated with membrane blebbing.29,30 It is also possible that increased SMPDL3b levels (as observed in DKD) lead to increased cellular sphingosine, which is a ceramide metabolite. This finding could explain why we detected decreased cellular ceramide levels in kidney cortexes from db/db mice (Figure 4). In support of this possibility, an increased sphingosine content in glomerular mesangial cells in db/db mice was previously described,31 and increased sphingosine levels in the presence of decreased SM and ceramide levels were observed in adipocytes of ob/ob mice.32 Thus, increased sphingosine production could explain why we observed increased apoptosis, cell blebbing, and RhoA activation in suPAR-treated SMPDL3b OE podocytes (Figures 3 and 7). Rho kinase was previously shown to play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression in DKD, and Rho kinase inhibition decreases glomerular injury in diabetic animal models.28,33 Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), another metabolite of ceramide, was shown to affect RhoA and Rac1 activity. In vascular smooth muscle cells, S1P binding to the receptor S1P3 leads to RhoA activation.34 In contrast, in human and mouse endothelial cells, S1P-induced cell migration was shown to occur by activation of Rac1.35 Increased S1P production as a result of increased ceramide metabolism could, therefore, explain the migratory phenotype observed in SMPDL3b KD podocytes (Figure 6) and the decreased ceramide levels observed in kidney cortexes of ADR-treated mice (Figure 4).

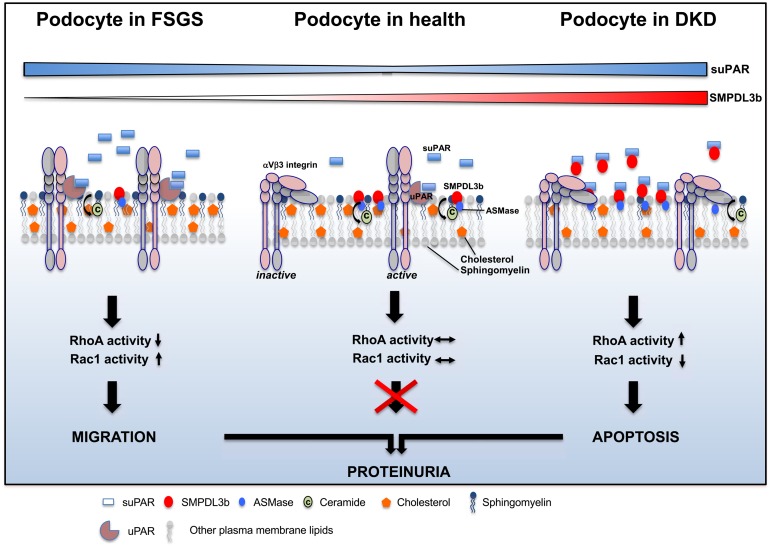

uPAR, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, is a cellular receptor for urokinase36 and signals through association with other transmembrane receptors, including integrin.37 Previous reports showed that uPAR translocates to the lipid raft domain in podocytes after LPS stimulation and that blocking of its localization to the lipid raft by cyclodextrin can prevent the β3 integrin activation.24 Co-IP experiments in transfected HEK293 cells revealed interaction of SMPDL3b with uPAR but not with β3 integrin, and SMPDL3b/uPAR interaction was further confirmed in glomeruli isolated from C57Bl/6 mice. Using competitive Co-IP, we show that SMPDL3b interferes with binding of suPAR/uPAR and β3 integrin, attenuating β3 integrin activation and signaling (Figure 5). We show that, in SMPDL3b KD podocytes, suPAR/uPAR-mediated β3 integrin activation and signaling are functional, whereas they are impaired in SMPDL3b OE podocytes (Figure 6). Our results suggest that, in the absence of SMPDL3b, suPAR can activate β3 integrin signaling (FSGS), whereas in the presence of SMPDL3b, SMPDL3b binds to suPAR, preventing β3 integrin activation (DKD). The mechanistic model for podocyte damage suggested by our findings is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Mechanistic model of podocyte injury in FSGS and DKD. In FSGS, increased circulating suPAR together with low or absent SMPDL3b expression lead to αVβ3 integrin activation, resulting in increased Src phosphorylation and Rac1 activity and ultimately causing a migratory podocyte phenotype. In DKD, increased circulating suPAR in the presence of high SMPDL3b expression leads to competitive binding of SMPDL3b to suPAR, thus preventing αVβ3 integrin activation but allowing for RhoA activation and increased apoptosis.

Furthermore, our study shows that suPAR increases Rac1 activity in SMPDL3b KD podocytes (Figure 6) and that an ASMase inhibitor worsens proteinuria in a model of FSGS (Figure 8), which may be because of decreased Smpdl3b expression in podocytes. On the contrary, suPAR increases RhoA activity in SMPDL3b OE podocytes (Figure 7) and diabetic animals, and an ASMase inhibitor ameliorates proteinuria in an in vivo model of DKD, possibly because of increased Smpdl3b expression in podocytes (Figures 4 and 9). However, we were not able to detect regulation of Smpdl3b in RNA isolated from kidney cortexes of these mice, which may be explained by the fact that podocytes represent only a very small percentage of the cells present in the kidney.

In summary, our study suggests an important role for podocyte SMPDL3b expression in the pathogenesis of FSGS and DKD. We show that high circulating suPAR levels are necessary but not sufficient to induce podocyte injury in FSGS and DKD. We also show that, in the presence of high suPAR levels, reduced podocyte SMPDL3b expression leads to activation of β3 integrin signaling and Rac1 and induction of a migratory, FSGS-like podocyte phenotype. In contrast, high suPAR in the presence of increased podocyte SMPDL3b levels will not allow for β3 integrin activation but will lead to RhoA activation and podocyte apoptosis. The fact that ASMase inhibition partially prevented proteinuria and the increase in glomerular surface area (within limitations of the method used38) underlines the potential role of SMPDL3b in DKD.

To our knowledge, this study shows, for the first time, how suPAR can affect the same cell through a different effector pathway, thus challenging the concept that targeted interventions to treat FSGS are also suitable for the treatment of DKD. Furthermore, our study suggests that, in addition to the removal or neutralization of suPAR, therapeutic targeting of SMPDL3b expression in podocytes may prove beneficial for the treatment of FSGS and DKD.

Concise Methods

Affymetrix Gene Chip Analyses of Human Glomeruli and Microarray Data in Human Glomeruli

Renal biopsy samples from healthy pretransplant kidney donors (n=32) and patients with primary FSGS (n=18) were obtained from the European Renal cDNA Bank following the guidelines of the respective local ethics committees.39 For glomerular mRNA expression profiles specific to patients with DKD, kidney biopsy specimens were procured from 70 Southwestern American Indians enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the renoprotective efficacy of losartan in type 2 diabetes.40 Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The biopsy tissue specimens were manually microdissected,41–43 and glomerular gene expression profiling was performed as previously described.15

Measurements of suPAR

Circulating suPAR levels were determined in the sera from 53 patients with FSGS from the FSGS clinical trial25 and 30 patients with type 1 diabetes and normoalbuminuria, 34 patients with type 1 diabetes and microalbuminuria, and 10 patients with type 1 diabetes and macroalbuminuria from the FinnDiane study cohort using Quantikine Human uPAR Immunoassay (R&D Systems) performed following the manufacturer’s protocol. Among those patients, only 40 patients had two sample collections for longitudinal determination of suPAR, and the clinical characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Patients belonging to the high-risk group of FSGS were defined by an onset age of <15 years or progression to a GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 within 6 months after onset of disease. Urinary albumin excretion rate was assessed from two of three urine collections as normal albumin excretion rate (<30 mg/24 h), microalbuminuria (≥30 to <300 mg/24 h), and macroalbuminuria (≥300 mg/24 h).

Animal Studies and Glomerular Isolation

All animal procedures were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Thirty-two 7- to 8-week-old BALB/C mice were used. FSGS-like lesions were induced by single intravenous ADR (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) injection (12 mg/kg). Eight mice were injected with ADR, eight mice were injected with ADR and desipramine hydrochloride, eight mice were injected with desipramine hydrochloride, and eight mice without treatment served as a control group. Desipramine hydrochloride, an ASMase inhibitor (10 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intraperitoneally every other day for 4 weeks. Mice were euthanized after 4 weeks. Sixteen B6.Cg-m+/+Leprdb/Leprdb (db/db) and sixteen B6.Cg-m+/+Leprdb/+ (db/+) female mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). At 8 weeks of age, eight db/db and eight db/+ mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 mg/kg ASMase inhibitor every other day for 12 weeks. At euthanasia, mice were perfused, kidneys were fixed, and glomerular protein lysates were prepared as described.15 Body weight and random glycemia were measured monthly, and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratios were determined at baseline and euthanasia. Blood glucose levels and urinary albumin content were determined as previously described.15 Circulating suPAR levels were measured in serum using the DuoSet ELISA Development Kit (DY531; R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Values are expressed as picograms suPAR per milliliter serum. Periodic acid–Schiff staining of 3-µm-thick slides was performed for the analysis of segmental sclerosis in ADR mice as previously described.15 For glomerular volume determination, the glomerular surface was delineated, and the mean surface area was then calculated as previously described.44 Determination of the lipid content in kidney cortexes was determined by the Wake Forest University Bioanalytical Laboratory, Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, according to their standard protocols.

Co-IP, Competitive Co-IP, and Endogenous Immunoprecipitation

Co-IP experiments were performed following the previous published protocols.11 For Co-IP experiments, HEK-293 cells were transfected with 1 μg plasmid containing GFP-SMPDL3b and FLAG-empty vector, FLAG-uPAR/suPAR, or FLAG-β3 integrin. For competitive Co-IP experiments, HEK-293 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of GFP-tagged SMPDL3b cDNA or a plasmid containing a GFP-tag without any fused cDNA (empty vector) together with 1 μg each FLAG-suPAR/uPAR and GFP-β3 integrin plasmid in HEK-293 cells. For endogenous immunoprecipitation experiments, C57Bl/6 mice were injected with LPS (250 μg) or vehicle (PBS), and glomeruli were prepared by sieving technique 24 hours later. To immunoprecipitate endogenous protein complexes, protein lysates of the isolated mouse glomeruli were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. One milliliter mouse glomerular extract solution was incubated for 1 hour with the dynabeads M-270 Epoxy (Invitrogen) coupled with antibodies (SMPDL3b; Genway or uPAR; R&D Systems) at 4°C under rotation. Immune complexes were eluted in 60 μl elution buffer. Both eluates and protein lysates (input) were loaded for Western blot analysis.

Podocyte Culture, Protein Extraction, and Western Blotting

Normal human podocytes were cultured as described.15,45 Stable SMPDL3b OE or SMPDL3b KD podocyte cell lines were previously described.7

Differentiated podocytes were serum-restricted for 24 hours followed by 24 hours of treatment with recombinant suPAR (1 μg/ml; R&D Systems) and cyclo RGD, a cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp) peptide (1 μg/ml; Enzo Life Sciences) with 4% patient serum from the FinnDiane study cohort of patients with DKD15 or pretransplant serum from patients with high risk for FSGS recurrence after transplant7 if not indicated otherwise; 22 pretransplant FSGS patient sera, five age-matched control sera, and 30 patient sera from the FinnDiane study were used as previously described.7,15

Glomeruli or cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) or 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic (CHAPS) acid buffer. Western blot analysis was performed as previously described15 using the following primary antibodies: anti-AP5, anti-AP3 (1:1000; Gen-Probe, Wakukesha, WI), antiphospho-Src, anti-Src (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Temecula, CA), anticleaved caspase-3 (1:250; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Gapdh (1:5000; Calbiochem), anti-FLAG (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-GFP (1:1000; Abcam, Inc.), and anti-SMPDL3b (1:1000; Novus Bio). Anti-mouse IgG HRP (1:10,000; Promega) or anti-rabbit IgG HRP (1:10,000; Promega) was used as secondary antibody.

Immunofluorescence Staining

A standard immunofluorescence protocol was followed. AP5 and AP3 monoclonal mouse antibodies (Gen-Probe), polyclonal anti-rabbit synaptopodin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or active RhoA mouse mAb (New East Biosciences) were used. Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies from Invitrogen were used. Images were acquired by confocal microscopy.

Transwell Migration Assay

Transwell migration assay was performed as previously described46 using normal, SMPDL3b KD, or SMPDL3b OE podocytes untreated or treated with recombinant human suPAR (1 μg/ml; R&D Systems).

Apoptosis Analyses

Apoptosis in human podocytes treated with the sera from patients with FSGS, DKD, or suPAR was assessed as previously described15 using the Caspase 3/CPP32 Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Inc.) or the Caspase 3 HTS Kit (Biotium). Absorbance values were expressed as fold change to controls.

Rac1 and RhoA Activity Assay

Rac1 and RhoA activity was assessed using the Rac1 Activation Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs) and RhoA pull-down assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturers’ protocols. After 24 hours of recombinant suPAR (1 μg/ml) treatment, podocyte lysates were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour with agarose beads specific for the p21-binding domain of p21-activated protein kinase (Rac1 pull-down assay) or glutathione-sepharose beads coupled with glutathione-S-transferase–Rhodekin fusion protein for determination of RhoA activity. Expression analysis was performed by Western blotting using anti-Rac1 and RhoA antibody.

Statistical Analyses

Values are expressed as means and SDs. Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS for Windows, version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Results were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test for multiple comparisons. Significant differences were confirmed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed to determine changes in suPAR levels between baseline and 7 years in the FinnDiane study group. Pearson correlation analysis was used to clarify the relationship between suPAR levels and GFR decline slope in FSGS patients. P values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

C.W., J.R., G.W.B., A.F., and S.M. are inventors on pending or issued patents aimed to diagnose or treat proteinuric renal diseases. They stand to gain royalties from their future commercialization. A.F. is a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche and Mesoblast on subject matters that are unrelated to this publication.

Acknowledgments

Nurses A. Sandelin and J. Tuomikangas at the Folkhälsan Institute of Genetics are acknowledged for their contribution to this work. We also thank the FinnDiane Study Group for their valuable contributions.

This study was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Part of this project was supported by Grant 1UL-1TR00046 (University of Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. This study was supported by Yonsei University College of Medicine Faculty Research Grant 6-2013-0143 (to T.-H.Y.) for 2013. The study was also supported by the Wilhelm and Else Stockmann Foundation (M.L. and P.-H.G.), the Novo Nordisk Foundation (M.L. and P.-H.G.), the Folkhälsan Research Foundation (P.-H.G.), and Academy of Finland Grant 134379 (to P.-H.G.). J.R. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK089394, R01-DK073495, and R01-DK101350. G.W.B., A.F., and S.M. are supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK090316. A.F. and S.M. are supported by the Diabetes Research Institute Foundation, the Nephcure Foundation, the Peggy and Harold Katz Family Foundation, and the Diabetic Complications Consortium (DiaComp). S.M. is supported by a Stanley J. Glaser Foundation Research Award.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Kim YH, Goyal M, Kurnit D, Wharram B, Wiggins J, Holzman L, Kershaw D, Wiggins R: Podocyte depletion and glomerulosclerosis have a direct relationship in the PAN-treated rat. Kidney Int 60: 957–968, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagtalunan ME, Miller PL, Jumping-Eagle S, Nelson RG, Myers BD, Rennke HG, Coplon NS, Sun L, Meyer TW: Podocyte loss and progressive glomerular injury in type II diabetes. J Clin Invest 99: 342–348, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer TW, Bennett PH, Nelson RG: Podocyte number predicts long-term urinary albumin excretion in Pima Indians with Type II diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabetologia 42: 1341–1344, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White KE, Bilous RW, Marshall SM, El Nahas M, Remuzzi G, Piras G, De Cosmo S, Viberti G: Podocyte number in normotensive type 1 diabetic patients with albuminuria. Diabetes 51: 3083–3089, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faul C, Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Kim K, Mundel P: Actin up: Regulation of podocyte structure and function by components of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol 17: 428–437, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wymann MP, Schneiter R: Lipid signalling in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 162–176, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fornoni A, Sageshima J, Wei C, Merscher-Gomez S, Aguillon-Prada R, Jauregui AN, Li J, Mattiazzi A, Ciancio G, Chen L, Zilleruelo G, Abitbol C, Chandar J, Seeherunvong W, Ricordi C, Ikehata M, Rastaldi MP, Reiser J, Burke GW, 3rd: Rituximab targets podocytes in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Sci Transl Med 3: 85ra46, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattran D, Neogi T, Sharma R, McCarthy ET, Savin VJ: Serial estimates of serum permeability activity and clinical correlates in patients with native kidney focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 448–453, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy ET, Sharma M, Savin VJ: Circulating permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2115–2121, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savin VJ, Sharma R, Sharma M, McCarthy ET, Swan SK, Ellis E, Lovell H, Warady B, Gunwar S, Chonko AM, Artero M, Vincenti F: Circulating factor associated with increased glomerular permeability to albumin in recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 334: 878–883, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asanuma K, Kim K, Oh J, Ciardino L, Chabanis S, Faul C, Reiser J, Mundel P: Synaptopodin regulates the actin-bundling activity of alpha-actinin in an isoform-specific manner J Clin Invest 115: 1188–1198, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández-Real JM, Vendrell J, García I, Ricart W, Vallès M: Structural damage in diabetic nephropathy is associated with TNF-α system activity. Acta Diabetol 49: 301–305, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohda T, Niewczas MA, Ficociello LH, Walker WH, Skupien J, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Johnson AC, Crabtree G, Smiles AM, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict stage 3 CKD in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 516–524, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eugen-Olsen J, Andersen O, Linneberg A, Ladelund S, Hansen TW, Langkilde A, Petersen J, Pielak T, Møller LN, Jeppesen J, Lyngbaek S, Fenger M, Olsen MH, Hildebrandt PR, Borch-Johnsen K, Jørgensen T, Haugaard SB: Circulating soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor predicts cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mortality in the general population. J Intern Med 268: 296–308, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merscher-Gomez S, Guzman J, Pedigo CE, Lehto M, Aguillon-Prada R, Mendez A, Lassenius MI, Forsblom C, Yoo T, Villarreal R, Maiguel D, Johnson K, Goldberg R, Nair V, Randolph A, Kretzler M, Nelson RG, Burke GW, 3rd, Groop PH, Fornoni A, FinnDiane Study Group : Cyclodextrin protects podocytes in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 62: 3817–3827, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Walker WH, Rosetti F, Cullere X, Eckfeldt JH, Doria A, Mayadas TN, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 507–515, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heraclides A, Jensen TM, Rasmussen SS, Eugen-Olsen J, Haugaard SB, Borch-Johnsen K, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, Witte DR: The pro-inflammatory biomarker soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is associated with incident type 2 diabetes among overweight but not obese individuals with impaired glucose regulation: Effect modification by smoking and body weight status. Diabetologia 56: 1542–1546, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sehestedt T, Lyngbæk S, Eugen-Olsen J, Jeppesen J, Andersen O, Hansen TW, Linneberg A, Jørgensen T, Haugaard SB, Olsen MH: Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is associated with subclinical organ damage and cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis 216: 237–243, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Backes Y, van der Sluijs KF, Mackie DP, Tacke F, Koch A, Tenhunen JJ, Schultz MJ: Usefulness of suPAR as a biological marker in patients with systemic inflammation or infection: A systematic review. Intensive Care Med 38: 1418–1428, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bock CE, Wang Y: Clinical significance of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression in cancer. Med Res Rev 24: 13–39, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toldi G, Szalay B, Bekő G, Bocskai M, Deák M, Kovács L, Vásárhelyi B, Balog A: Plasma soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. Biomarkers 17: 758–763, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankland SJ, Pollak MR: A suPAR circulating factor causes kidney disease. Nat Med 17: 926–927, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trachtman H, Gipson DS, Kaskel F, Ghiggeri GM, Faul C, Gupta V, Fornoni A, Burke GW, 3rd, Thomas DB, Barisoni L, Schaefer F, Wei C, Reiser J: Regarding Maas’s editorial letter on serum suPAR levels. Kidney Int 82: 492, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei C, Möller CC, Altintas MM, Li J, Schwarz K, Zacchigna S, Xie L, Henger A, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Cowan P, Kretzler M, Parrilla R, Bendayan M, Gupta V, Nikolic B, Kalluri R, Carmeliet P, Mundel P, Reiser J: Modification of kidney barrier function by the urokinase receptor. Nat Med 14: 55–63, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei C, Trachtman H, Li J, Dong C, Friedman AL, Gassman JJ, McMahan JL, Radeva M, Heil KM, Trautmann A, Anarat A, Emre S, Ghiggeri GM, Ozaltin F, Haffner D, Gipson DS, Kaskel F, Fischer DC, Schaefer F, Reiser J, PodoNet and FSGS CT Study Consortia : Circulating suPAR in two cohorts of primary FSGS. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 2051–2059, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B, Xie S, Shi W, Yang Y: Amiloride off-target effect inhibits podocyte urokinase receptor expression and reduces proteinuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 1746–1755, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huveneers S, Danen EH: Adhesion signaling - crosstalk between integrins, Src and Rho. J Cell Sci 122: 1059–1069, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peng F, Wu D, Gao B, Ingram AJ, Zhang B, Chorneyko K, McKenzie R, Krepinsky JC: RhoA/Rho-kinase contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic renal disease. Diabetes 57: 1683–1692, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tepper AD, Ruurs P, Wiedmer T, Sims PJ, Borst J, van Blitterswijk WJ: Sphingomyelin hydrolysis to ceramide during the execution phase of apoptosis results from phospholipid scrambling and alters cell-surface morphology. J Cell Biol 150: 155–164, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taha TA, Hannun YA, Obeid LM: Sphingosine kinase: Biochemical and cellular regulation and role in disease. J Biochem Mol Biol 39: 113–131, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gennero I, Fauvel J, Nieto M, Cariven C, Gaits F, Briand-Mésange F, Chap H, Salles JP: Apoptotic effect of sphingosine 1-phosphate and increased sphingosine 1-phosphate hydrolysis on mesangial cells cultured at low cell density. J Biol Chem 277: 12724–12734, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samad F, Hester KD, Yang G, Hannun YA, Bielawski J: Altered adipose and plasma sphingolipid metabolism in obesity: A potential mechanism for cardiovascular and metabolic risk. Diabetes 55: 2579–2587, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolavennu V, Zeng L, Peng H, Wang Y, Danesh FR: Targeting of RhoA/ROCK signaling ameliorates progression of diabetic nephropathy independent of glucose control. Diabetes 57: 714–723, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryu Y, Takuwa N, Sugimoto N, Sakurada S, Usui S, Okamoto H, Matsui O, Takuwa Y: Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a platelet-derived lysophospholipid mediator, negatively regulates cellular Rac activity and cell migration in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 90: 325–332, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heller R, Chang Q, Ehrlich G, Hsieh SN, Schoenwaelder SM, Kuhlencordt PJ, Preissner KT, Hirsch E, Wetzker R: Overlapping and distinct roles for PI3Kbeta and gamma isoforms in S1P-induced migration of human and mouse endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res 80: 96–105, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith HW, Marshall CJ: Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 23–36, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blasi F, Carmeliet P: uPAR: A versatile signalling orchestrator. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 932–943, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, Zimanyi MA, Bertram JF: Towards a definition of glomerulomegaly: Clinical-pathological and methodological considerations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 2202–2208, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yasuda Y, Cohen CD, Henger A, Kretzler M, European Renal cDNA Bank (ERCB) Consortium : Gene expression profiling analysis in nephrology: Towards molecular definition of renal disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 10: 91–98, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weil EJ, Fufaa G, Jones LI, Lovato T, Lemley KV, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Yee B, Myers BD, Nelson RG: Effect of losartan on prevention and progression of early diabetic nephropathy in American Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 62: 3224–3231, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berthier CC, Zhang H, Schin M, Henger A, Nelson RG, Yee B, Boucherot A, Neusser MA, Cohen CD, Carter-Su C, Argetsinger LS, Rastaldi MP, Brosius FC, Kretzler M: Enhanced expression of Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway members in human diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 58: 469–477, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen CD, Frach K, Schlöndorff D, Kretzler M: Quantitative gene expression analysis in renal biopsies: A novel protocol for a high-throughput multicenter application. Kidney Int 61: 133–140, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M, Boucherot A, Berra S, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Eichinger F, Gaiser S, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, Schrier RW, Schlöndorff D, Cohen CD: Interstitial vascular rarefaction and reduced VEGF-A expression in human diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1765–1776, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doi T, Striker LJ, Quaife C, Conti FG, Palmiter R, Behringer R, Brinster R, Striker GE: Progressive glomerulosclerosis develops in transgenic mice chronically expressing growth hormone and growth hormone releasing factor but not in those expressing insulinlike growth factor-1. Am J Pathol 131: 398–403, 1988 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saleem MA, O’Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P: A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 630–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Faul C, Tomino Y, Kim K, Mundel P: Synaptopodin orchestrates actin organization and cell motility via regulation of RhoA signalling. Nat Cell Biol 8: 485–491, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]