Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor-23 is a bone-derived hormone that increases urinary phosphate excretion and inhibits hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Recent studies suggest that fibroblast growth factor-23 may be an early biomarker of CKD progression. However, its role in kidney function decline in the general population is unknown. We assessed the relationship between baseline (1990–1992) serum levels of intact fibroblast growth factor-23 and incident ESRD in 13,448 Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study participants (56.1% women, 74.7% white) followed until December 31, 2010. At baseline, the mean age of participants was 56.9 years and the mean eGFR was 97 ml/min per 1.73 m2. During a median follow-up of 19 years, 267 participants (2.0%) developed ESRD. After adjustment for demographic characteristics, baseline eGFR, traditional CKD risk factors, and markers of mineral metabolism, the highest fibroblast growth factor-23 quintile (>54.6 pg/ml) compared with the lowest quintile (<32.0 pg/ml) was associated with risk of developing ESRD (hazard ratio, 2.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.31 to 3.36; trend P<0.001). In a large, community-based study comprising a broad range of kidney function, higher baseline fibroblast growth factor-23 levels were associated with increased risk of incident ESRD independent of the baseline level of kidney function and a number of other risk factors.

Keywords: ESRD, mineral metabolism, risk factors

CKD is a global public health problem due to its high prevalence and strong association with cardiovascular disease, ESRD, and mortality.1–4 Exploring novel biomarkers for risk of future CKD, particularly among those with relatively preserved kidney function, may contribute to understanding of CKD pathogenesis and new targets for therapy. Fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) was recently proposed as an early indicator of kidney injury.5,6

FGF-23 is a 32-kD bone-derived hormone with several endocrine functions in the kidney, including the promotion of urinary phosphate excretion and the inhibition of the hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, to reduce the production of the active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.7 Recent studies suggest that FGF-23 is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease as well as all-cause mortality, and that these associations may be stronger among persons with CKD.8–15 Furthermore, higher levels of FGF-23 are linked to kidney disease progression in persons with established CKD, although this association may not be independent of baseline eGFR and albuminuria.11,16,17 There is limited information about the association between FGF-23 and the development of CKD in the general population.

The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that higher baseline serum levels of intact FGF-23 are associated with an elevated risk of incident kidney disease, independent of baseline kidney function and a large number of risk factors among participants of the community-based Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

Results

Participant Baseline Characteristics

There were 13,448 ARIC study participants. Of the participants, 72.7% had a creatinine-based eGFR (eGFRCr)≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 based on the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation, 25.3% had eGFRCr of 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and 2.0% had eGFRCr<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Overall, 56.1% of participants were women and 74.7% were white. The mean age was 56.9 years and the mean baseline eGFRCr was 97 ml/min per 1.73 m2. At baseline, participants with higher FGF-23 levels were more likely to have eGFRCr<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, diabetes, or a history of coronary heart disease and were more likely to use antihypertensive medications (Table 1). Participants with higher FGF-23 levels also had higher blood concentrations of parathyroid hormone, phosphate, calcium, and β2-microglobulin, as well as lower eGFRCr (r=–0.21), cystatin C–based eGFR (eGFRCys) (r=–0.27), and creatinine-based and cystatin C–based eGFR (eGFRCr-Cys) (r=–0.27). FGF-23 was weakly, positively correlated with calcium only among those with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, r=0.12; eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, r=0.02).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by quintile of serum level of FGF-23 in the ARIC study (1990–2010; n=13,448)

| Characteristic | Quintile of Serum Level of FGF-23 (pg/ml) | P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (<32.0) | 2 (32.0–38.5) | 3 (38.6–45.3) | 4 (45.4–54.6) | 5 (>54.6) | ||

| Participants (n) | 2690 | 2690 | 2689 | 2690 | 2689 | |

| Median FGF-23 (pg/ml) | 27.5 | 35.6 | 41.9 | 49.5 | 63.5 | <0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 56.3 (5.7) | 56.6 (5.7) | 56.7 (5.7) | 57.2 (5.7) | 57.6 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Women | 60.0 | 56.8 | 54.1 | 53.0 | 56.4 | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 74.1 | 76.6 | 76.7 | 74.2 | 72.1 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.0 (5.4) | 27.7 (5.3) | 28.0 (5.2) | 28.3 (5.4) | 29.1 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 53.0 (17.6) | 50.6 (16.6) | 49.4 (16.5) | 48.0 (16.1) | 47.5 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes status | 14.3 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 15.2 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 120.0 (18.3) | 120.7 (18.4) | 121.0 (18.3) | 122.0 (19.1) | 123.7 (19.6) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 25.9 | 28.0 | 30.5 | 34.9 | 45.6 | <0.001 |

| History of coronary heart disease | 4.3 | 5.4 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | ||||||

| eGFRCr category | ||||||

| <60 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 6.5 | <0.001 |

| 60–89 | 18.7 | 22.0 | 24.9 | 29.3 | 31.6 | <0.001 |

| ≥90 | 80.9 | 77.4 | 74.3 | 69.1 | 61.9 | <0.001 |

| eGFRCr | 100.0 (13.9) | 98.1 (13.7) | 97.3 (14.2) | 95.6 (15.1) | 91.7 (19.1) | <0.001 |

| eGFRCys | 96.3 (16.2) | 93.8 (16.3) | 92.4 (16.6) | 89.1 (17.8) | 82.5 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| eGFRCr-Cys | 100.5 (15.3) | 97.7 (14.9) | 96.4 (15.1) | 93.6 (16.3) | 87.9 (19.8) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 4.41 (8.87) | 3.98 (5.99) | 4.06 (5.96) | 4.43 (6.86) | 5.07 (7.81) | <0.001 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml) | 40.5 (20.4) | 41.3 (15.6) | 41.7 (15.6) | 42.8 (16.6) | 45.1 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.47 (0.47) | 3.51 (0.47) | 3.51 (0.47) | 3.56 (0.47) | 3.63 (0.52) | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.28 (0.41) | 9.31 (0.44) | 9.33 (0.40) | 9.39 (0.42) | 9.45 (0.46) | <0.001 |

| β2-Microglobulin (mg/L) | 1.80 (0.41) | 1.84 (0.43) | 1.88 (0.40) | 1.95 (0.47) | 2.19 (1.07) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as the mean (SD) or percentage unless otherwise specified.

ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables.

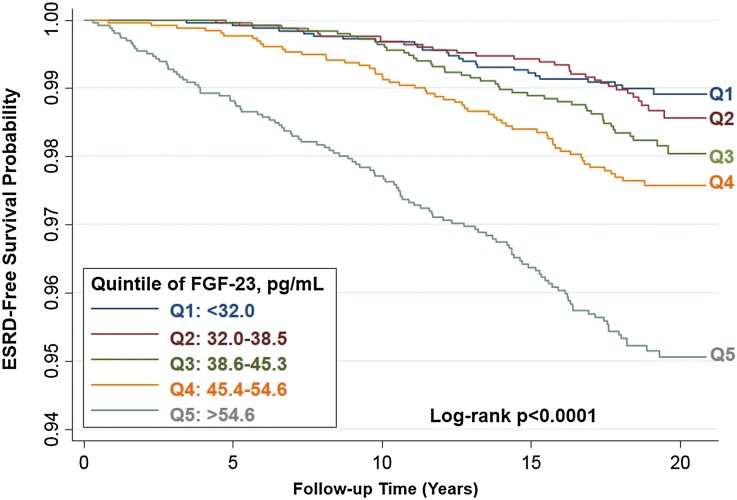

FGF-23 Level Associated with Risk of ESRD

During a median follow-up of 19 years, 267 participants (2.0%) had developed ESRD. Those participants with baseline levels of FGF-23 in higher quintiles had a higher cumulative incidence of ESRD (log-rank P<0.001; Figure 1). For example, participants with baseline levels of FGF-23 in the highest quintile (corresponding to >54.6 pg/ml) developed ESRD at nearly five times the rate of those with FGF-23 levels in the lowest quintile (corresponding to <32.0 pg/ml; hazard ratio [HR], 4.88; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 3.16 to 7.52; P for trend across all quintiles, P<0.001; Table 2, model 1).

Figure 1.

Probability of survival without incident ESRD is lower among those with higher quintiles of baseline serum level of FGF-23.

Table 2.

Frequency, incidence rates, HRs, and 95% CIs for incident ESRD by quintile of serum levels of FGF-23 in the ARIC study (1990–2010; n=13,448)

| Rate | Quintile of Serum Level of FGF-23 (pg/ml) | P Value for Trenda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (<32.0) | 2 (32.0–38.5) | 3 (38.6–45.3) | 4 (45.4–54.6) | 5 (>54.6) | ||

| Participants (n) | 2690 | 2690 | 2689 | 2690 | 2689 | |

| Events | 25 (0.9) | 30 (1.1) | 43 (1.6) | 56 (2.1) | 113 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Incidence rateb | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.78) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.90) | 0.91 (0.67 to 1.22) | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.57) | 2.55 (2.12 to 3.06) | <0.001 |

| Modelc | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Ref] | 1.19 (0.70 to 2.03) | 1.72 (1.05 to 2.81) | 2.30 (1.43 to 3.68) | 4.88 (3.16 to 7.52) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1 [Ref] | 1.20 (0.70 to 2.04) | 1.72 (1.05 to 2.82) | 2.18 (1.36 to 3.50) | 4.47 (2.89 to 6.90) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 1 [Ref] | 1.10 (0.65 to 1.87) | 1.41 (0.86 to 2.32) | 1.42 (0.88 to 2.28) | 1.92 (1.23 to 3.02) | <0.001 |

| 4 | 1 [Ref] | 1.08 (0.63 to 1.85) | 1.48 (0.90 to 2.45) | 1.33 (0.82 to 2.17) | 1.97 (1.25 to 3.11) | <0.001 |

| 5 | 1 [Ref] | 1.10 (0.64 to 1.91) | 1.58 (0.95 to 2.64) | 1.37 (0.83 to 2.25) | 2.10 (1.31 to 3.36) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or HR (95% CI) unless otherwise specified. Ref, reference group.

Linear trend across the quintiles using the median of each quintile.

Unadjusted incidence rate (95% CI) per 1000 person-years.

Models are as follows: model 1 is unadjusted (no covariates included in the model); model 2 is adjusted for age, sex, and race; model 3 is adjusted for the variables in model 2 plus eGFRCr, eGFRCys, and eGFRCr-Cys; model 4 is adjusted for the variables in model 3 plus diabetes, systolic BP, antihypertensive medication, HDL cholesterol, body mass index, C-reactive protein, and β2-microglobulin; and model 5 is adjusted for variables in model 4 plus phosphate, calcium, and parathyroid hormone.

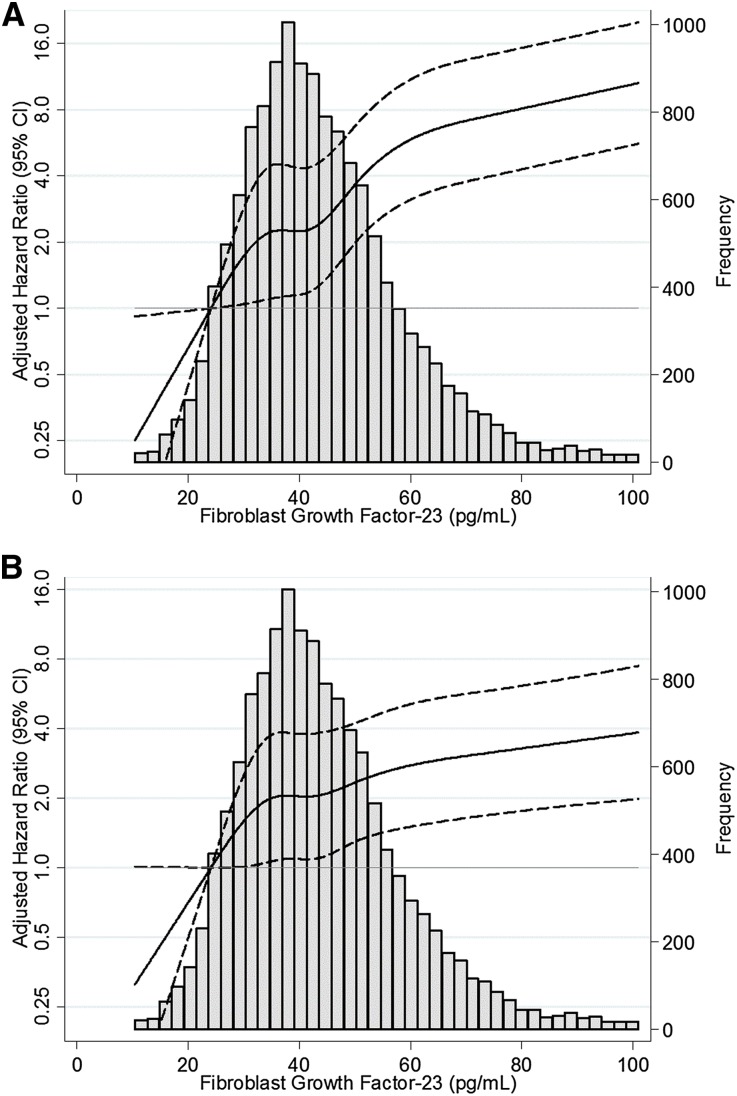

In demographic-adjusted analyses, the relationship between higher FGF-23 and increased risk of ESRD remained (Figure 2A). For example, participants with levels of FGF-23 in the highest quintile had a risk of ESRD that was 4.47 times higher than those in the lowest quintile (95% CI, 2.89 to 6.90; P for trend across all quintiles, P<0.001; Table 2, model 2).

Figure 2.

Relative hazard of ESRD is higher at higher baseline levels of FGF-23. (A) Adjusted for age, sex, and race. (B) Adjusted for age, sex, race, eGFRCr-Cys, diabetes, systolic BP, antihypertensive medication, HDL cholesterol, body mass index, C-reactive protein, β2-microglobulin, phosphate, calcium, and parathyroid hormone. Restricted cubic spline with knots at 24.1, 34.8, 41.9, 50.6, and 72.3 pg/ml. The shaded area represents the 95% CI.

After adjustment for baseline eGFRCr-Cys, risk estimates for ESRD associated with FGF-23 quintile were substantially attenuated but remained statistically significant (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.23 to 3.02; Table 2, model 3). Results were qualitatively similar after adjusting for other estimates of GFR (quintile 5 versus quintile 1: HR adjusted for age, sex, race, and eGFRCr, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.67 to 4.05; HR adjusted for age, sex, race, and eGFRCys, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.29 to 3.14).

In fully adjusted models, higher FGF-23 levels were associated with a higher risk of ESRD (Figure 2B). For each 10-pg/ml increase of FGF-23, the fully adjusted risk of ESRD was 12% higher (model 5: HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.17; P<0.001). There was a 2.10-fold higher risk of ESRD for those in the highest FGF-23 quintile compared with those in the lowest quintile, after adjusting for demographics, eGFRCr-Cys, kidney disease risk factors, and markers of mineral metabolism (95% CI, 1.31 to 3.36; P for trend across all quintiles, P<0.001; Table 2, model 5).

There was no observed effect modification between FGF-23 and age, sex, or race. Baseline eGFR category was not a statistically significant effect modifier of the association between FGF-23 quintile and ESRD (P for interaction, P>0.20). However, given inherent interest, stratified analyses by baseline eGFR category were conducted. The association between FGF-23 and ESRD risk persisted when the sample was restricted to those with baseline eGFR≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (HR per 10-pg/ml FGF-23 increment, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.22; P=0.03; Table 3, model 5).

Table 3.

HRs and 95% CIs for ESRD per 10-pg/ml FGF-23 increment according to category of baseline kidney function in the ARIC study (1990–2010; n=13,448)

| eGFR Model (ml/min per 1.73 m2)a | Participants (n) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | P Value for Interactionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFRCr≥90 | ||||

| Model 1 | 9779 | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15) | <0.001 | — |

| Model 5 | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) | 0.03 | — | |

| eGFRCr 60–89 | 3404 | |||

| Model 1 | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | 0.001 | 0.78 | |

| Model 5 | 1.07 (0.95 to 1.21) | 0.25 | 0.56 | |

| eGFRCr<60 | 265 | |||

| Model 1 | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.13) | <0.001 | 0.60 | |

| Model 5 | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.23) | 0.03 | 0.21 |

Models are as follows: model 1 is unadjusted (no covariates included in the model); and model 5 is adjusted for age, sex, race, diabetes, systolic BP, antihypertensive medication, eGFRCr, eGFRCys, eGFRCr-Cys, HDL cholesterol, body mass index, C-reactive protein, β2-microglobulin, phosphate, calcium, and parathyroid hormone.

Interaction of GFR category using eGFRCr≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 as the reference group (all P>0.20). Dash represents reference group for test of interaction.

FGF-23 Level Associated with Risk of CKD

There were 1818 cases (13.8%) of incident CKD (n=13,180). A higher FGF-23 level at baseline was associated with incident CKD in the unadjusted analysis (quintile 5 versus quintile 1: HR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.51 to 2.02; P for trend across all quintiles, P<0.001; Table 4, model 1). This association was attenuated with adjustment for baseline eGFR, and was not statistically significant in the fully adjusted model (model 5, quintile 5 versus 1: HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.29; P for trend across all quintiles, P=0.07). In all models with FGF-23 as a continuous variable, FGF-23 was statistically significantly associated with incident CKD, independent of demographics, eGFRCr-Cys, kidney disease risk factors, and markers of mineral metabolism (model 1: HR per 10-pg/ml increment, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.10; P<0.001; model 5: HR per 10-pg/ml increment, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.06; P=0.03).

Table 4.

Frequency, incidence rates, HRs, and 95% CIs for incident CKD (hospitalizations and deaths) by quintile of serum levels of FGF-23 in the ARIC study (1990–2010; n=13,180)

| Rate | Quintile of Serum Level of FGF-23 (pg/ml) | P Value for Trenda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (<32.0) | 2 (32.0–38.5) | 3 (38.6–45.3) | 4 (45.4–54.6) | 5 (>54.6) | ||

| Participants (n) | 2678 | 2674 | 2665 | 2649 | 2514 | |

| Eventsb | 303 (11.3) | 307 (11.5) | 338 (12.7) | 410 (15.5) | 460 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| Incidence ratec | 6.76 (6.04 to 7.57) | 6.81 (6.09 to 7.61) | 7.55 (6.79 to 8.40) | 9.49 (8.62 to 10.5) | 11.6 (10.6 to 12.7) | <0.001 |

| Modeld | ||||||

| 1 | 1 [Ref] | 1.01 (0.86 to 1.18) | 1.12 (0.96 to 1.31) | 1.42 (1.22 to 1.65) | 1.74 (1.51 to 2.02) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1 [Ref] | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.15) | 1.08 (0.92 to 1.26) | 1.30 (1.12 to 1.51) | 1.59 (1.37 to 1.84) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 1 [Ref] | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.08) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.12) | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.25) | 1.20 (1.03 to 1.39) | 0.001 |

| 4 | 1 [Ref] | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.11) | 1.00 (0.86 to 1.18) | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.24) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.29) | 0.05 |

| 5 | 1 [Ref] | 0.95 (0.80 to 1.12) | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.18) | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.25) | 1.10 (0.94 to 1.29) | 0.06 |

Data are presented as n (%) or HR (95% CI) unless otherwise specified. Ref, reference group.

Linear trend across the quintiles using the median of each quintile.

Among all incident CKD patients, 20.5% (n=373) developed a eGFRCr<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and at least a 25% decline in eGFRCr, 7.9% (n=143) developed ESRD identified by the USRDS registry, and 71.6% (n=1302) had a CKD-related hospitalization or death.

Unadjusted incidence rate (95% CIs) per 1000 person-years.

Models are as follows: model 1 is unadjusted (no covariates included in the model); model 2 is adjusted for age, sex, and race; model 3 is adjusted for the variables in model 2 plus eGFRCr, eGFRCys, and eGFRCr-Cys; model 4 is adjusted for the variables in model 3 plus diabetes, systolic BP, antihypertensive medication, HDL cholesterol, body mass index, C-reactive protein, and β2-microglobulin; and model 5 is adjusted for variables in model 4 plus phosphate, calcium, and parathyroid hormone.

Phosphate Level Associated with Risk of ESRD

We used multivariable regression models to evaluate whether FGF-23 was a mediator of the relationship between phosphate and ESRD. When FGF-23 was excluded from the covariates, phosphate levels >3.5 mg/dl were significantly associated with higher risk of ESRD in models 1–3, but not in models 4 and 5 after accounting for β2-microglobulin. In models 3–5, when log10-transformed FGF-23 was added to the model, the association between phosphate level and ESRD was substantially attenuated and no longer statistically significant.

Sensitivity Analyses

To evaluate whether albuminuria confounded the association between FGF-23 and ESRD, a sensitivity analysis was performed with adjustment for the available data on the urine albumin/creatinine ratio (measured at study visit 4, 1996–1998, in 79.1% of participants) and restricting the analysis to incident ESRD after the measurement of urine albumin/creatinine ratio. Adjusting for the urine albumin/creatinine ratio did not materially affect the results. For example, in the full model (model 5), after adjusting for demographics, eGFRCr-Cys, kidney disease risk factors, markers of mineral metabolism, and urine albumin/creatinine ratio, there was a 1.85-times higher risk of ESRD for those in the highest FGF-23 quintile relative to the lowest quintile (95% CI, 1.02 to 3.37).

To assess the effect of misclassification of ESRD status as a result of death before RRT, analyses were repeated after accounting for the competing risk of death. The results of the competing risk analyses were consistent with the main findings.

Discussion

In a large, community-based study of middle-aged, healthy at enrollment, black and white men and women with up to 21 years of follow-up, higher baseline levels of FGF-23 were associated with an increased risk ESRD after adjustment for demographic characteristics, kidney function, other risk factors, and mineral metabolism markers. These findings were robust to sensitivity analyses accounting for the strong competing risk of death as well as in analyses adjusting for a measure of albuminuria.

Three studies have investigated the association between FGF-23 and kidney disease in CKD cohorts.11,16,17 In the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) cohort study of 177 participants with CKD (mean GFR 63.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2) followed for a median of 53 months, intact FGF-23 levels above the median value (35 pg/ml) were associated with kidney disease progression, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine concentration or need for RRT.16 This association was independent of age, sex, eGFRCr, proteinuria, and serum levels of calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone (HR per 10-pg/ml increment, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.11; P=0.01). In the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK), among 809 participants with CKD (mean GFR 45.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2) followed for a median of 7.9 years, the highest (≥64.4 pg/ml) versus lowest (≤30.7 pg/ml) quartile of intact FGF-23 level was associated with higher risk of ESRD or death, independent of demographics, kidney disease risk factors, kidney function (GFR, urine protein/creatinine ratio), and markers of mineral metabolism (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.34 to 3.83; P for trend, P<0.01).17 In the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study of 3879 participants with CKD (mean GFR 42.8 ml/min per 1.73 m2) followed for a median of 42 months, higher quartiles of C-terminal FGF-23 were associated with ESRD risk, but not after adjustment for eGFR.11 However, in a subgroup analysis, FGF-23 was independently associated with ESRD among participants with an eGFR of 30–45 ml/min per 1.73 m2and ≥45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, but not among those with eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Our findings are similar to some aspects of these three prior studies of FGF-23 and CKD progression. The cross-sectional relationships between FGF-23, eGFR, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone were similar in direction and magnitude in the ARIC, MMKD, AASK, and CRIC studies.11,16,17 Our fully adjusted risk estimates for ESRD, when expressed per 10-pg/ml increment of FGF-23, were very similar to those from the MMKD study (MMKD: HR per 10-pg/ml increment, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.11; P=0.01; ARIC: HR per 10-pg/ml increment, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.17; P<0.01).16 Our fully adjusted risk estimates for ESRD were also similar in magnitude to those from the AASK trial, with a 2-fold increased risk of ESRD for the highest versus lowest quantile.17

However, differences between this study and the CRIC study were noted in the relationship between FGF-23 and ESRD risk, which may be the because of adjustment factors, FGF-23 measurement, or the study populations. First, in the CRIC study, fully adjusted models included baseline albuminuria, a key risk factor that was not measured at baseline in the ARIC study. However, sensitivity analyses adjusting for albuminuria at ARIC study visit 4 did not substantially alter the observed relationship. Second, C-terminal FGF-23 was measured in the CRIC study, whereas intact FGF-23 was measured in the MMKD, AASK, and current ARIC studies. Whereas C-terminal FGF-23 levels appear to be correlated with FGF-23 bioactivity, intact FGF-23 is thought to be the biologically active moiety and the predominant circulating form of FGF-23 in the setting of renal impairment.18 Third, the study populations differ in that ARIC participants represent the range of kidney function seen in the general population. By contrast, the CRIC study specifically selected participants on the basis of having CKD.

In addition to analyses of ESRD, we report in this study that higher baseline levels of FGF-23 are associated with incident CKD after accounting for demographic characteristics and GFR. This relationship remained significant in some, but not all, models after adjusting for kidney disease risk factors and other markers of mineral metabolism. Our findings are generally consistent with the Women’s Health and Aging Study I that investigated the relationship between FGF-23 and incident CKD.19 Among 307 older, disabled women (median eGFR 70.3 ml/min per 1.73 m2) followed for a maximum of 2 years, a 1-SD increase (0.45 pg/ml) in log-transformed intact FGF-23 was associated with incident stage 3 CKD defined as eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, after adjusting for baseline eGFR, demographics, kidney disease risk factors, other markers of mineral metabolism, and history of cardiovascular disease (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.06 to 2.16; P=0.02). The stronger estimates of incident CKD risk in the Women’s Health and Aging Study I may be attributed to the older study population (mean age of 74 years versus 57 years in this study), a shorter follow-up period (2 years versus 21 years in this study), or differences in FGF-23 increments used for estimating risk. The observation that FGF-23 is more strongly related to incident ESRD than incident CKD in this study suggests that FGF-23 may be a marker of faster kidney disease progression.

There are several potential mechanisms to explain the association between FGF-23 and ESRD. First, FGF-23 may be a proxy for abnormalities of mineral metabolism, such as elevated phosphate. Higher circulating levels of phosphate may promote vascular calcification and lead to kidney injury due to calcium phosphate deposition in the kidney.20–22 However, our findings suggest that the association between FGF-23 and ESRD is statistically independent of serum phosphate and other markers of mineral metabolism, namely, calcium and parathyroid hormone. Another major role of FGF-23 is to inhibit 1α-hydroxylase activity in the kidney, reducing the conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D into the active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, that may in turn contribute to kidney disease progression.7,23 Animal studies have shown that elevated levels of active vitamin D contribute to factors that are hypothesized to be associated with a reduction of kidney disease progression, including reduction in proteinuria, decrease in TGF-β, inhibition of mesangial cell proliferation, and preservation of the structural integrity of glomerular podocytes.24–27 Finally, FGF-23 might directly contribute to kidney injury, similar to the direct effect of FGF-23 on cardiac myocytes.9 Previous studies suggest that FGF-23 elevation precedes abnormalities in other mineral metabolism markers, which supports the potential role of FGF-23 as an early indicator of renal pathology.28–30

This study has several strengths. The ARIC study is a large, well characterized cohort. The representation of men and women, African Americans and Caucasians, and four United States communities allows for relatively broad generalizability of the study results. Many important factors, including kidney function measured by multiple filtration markers as well as calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone, were measured and included in adjusted regression models. Participants were followed for an extended period (up to 21 years) and we identified cases of ESRD with linkage to the US Renal Data System (USRDS) registry.

Certain limitations are important to consider in interpreting these results. There was a single measurement of FGF-23 obtained from stored samples. Intact FGF-23 has high intraindividual biologic variability and preanalytical instability.31,32 However, the assay used in this study demonstrated the best analytical performance characteristics compared with other available commercial assays of intact FGF-23.33 Given that ARIC participants were selected to be representative of community-dwelling adults regardless of disease status, there were relatively few participants with a baseline eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. As such, there was limited statistical power to make definitive conclusions in this subgroup. We did not have baseline measurements of albuminuria, which is a strong risk factor for kidney failure.34 However, results were robust to adjustment for a measure of albuminuria at an intermediate time point. The incident CKD outcome in this study identifies stage 3 and worse, but not patients with CKD with proteinuria and preserved kidney filtration (CKD stages 1 and 2) due to the lack of albuminuria measurements. Furthermore, the incident CKD outcome is a composite of eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, 25% eGFR decline, USRDS-identified ESRD, hospitalizations, and deaths, with the majority of patients being identified through CKD-related hospitalizations and deaths. Given the long span of time between study visits and creatinine measurements, this composite variable was created to mitigate selection bias caused by potential differential loss to follow-up based on kidney disease status.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that high serum levels of intact FGF-23 are associated with an elevated risk of incident ESRD in a community-based population, independent of demographic characteristics, kidney disease risk factors, baseline eGFR, and mineral metabolism markers. Future research should investigate whether FGF-23 plays a direct role in kidney disease pathogenesis, separate from or in combination with other markers of mineral metabolism.

Concise Methods

Study Design and Study Participants

The ARIC study is a community-based cohort originally designed to study risk factors for cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis.35 The participants at enrollment (1987–1989) included 15,792 predominantly black and white men and women aged 45–64 years, randomly selected and recruited from four Unite States communities: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland. Of these, 14,348 participants (90.9%) attended ARIC study visit 2 during 1990–1992 (baseline for this study). Participants who attended ARIC study visit 2 (1990–1992), had stored serum samples, did not have ESRD at baseline, and were either black or white were eligible for inclusion in this study (n=13,448, 93.7%).

The institutional review board at each participating study center approved the study protocol, and all study participants provided written documentation of informed content. Procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurements

Study participants provided 12-hour fasting blood samples and spot urine samples at baseline (study visit 2, 1990–1992). Blood samples were centrifuged within 30 minutes of venipuncture at 3000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C, aliquoted into multiple vials, frozen at −70°C, shipped to the ARIC central laboratory, and stored at −70°C until analysis.

Several biochemical analyses were performed on the specimens as part of the original ARIC study visit 2 protocol (1990–1992). Fasting glucose was measured by the modified hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. HDL cholesterol levels were measured enzymatically after precipitation with dextran sulfate-magnesium.36 Creatinine was measured by the modified kinetic Jaffé method, and values were calibrated to the National Institute of Standards and Technology standard.37 GFR was estimated using standardized eGFRCr, eGFRCys, and eGFRCr-Cys by CKD-EPI estimating equations.38,39

Additional biochemical analyses were performed on these ARIC visit 2 stored blood samples in 2012–2013 at the University of Minnesota Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory and were quantified using the Roche Modular P800 Chemistry Analyzer unless otherwise specified (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Serum levels of intact FGF-23 were measured using a commercially available, two-site sandwich ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Kainos Laboratories, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). The coefficient of variation (CV) for FGF-23 based on ARIC blind duplicate samples was 16.6%, and the CV for internal laboratory quality control samples was 8.8% at 41.4 pg/ml. Serum β2-microglobulin was measured turbidimetrically after agglutination of antigens from the sample to latex-bound anti-β2-microglobulin antibodies (CV=5.9%–7.3%). Calcium and phosphate were measured using colorimetric methods (CV=2.3% and 2.2%, respectively). Intact parathyroid hormone was measured using a sandwich immunoassay and quantified using a Roche Elecsys 2010 Analyzer (CV=2.9%–5.1%). C-reactive protein was measured using a high-sensitivity latex-particle–enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay kit (CV=4.5%). Cystatin C was measured using a particle-enhanced turbidimetric assay (Gentian, Moss, Norway; CV=2.1%–3.5%).

Baseline information on demographic characteristics, lifestyle habits, medical history, and medication use was obtained using a questionnaire administered in person by trained interviewers at the same study visit 2 (1990–1992). Participants were classified as having diabetes if they had fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl, had nonfasting glucose ≥200 mg/dl, reported a history of diabetes, or were taking diabetes medication in the past 2 weeks. Three seated measurements of BP were taken by a certified technician using a random-zero sphygmomanometer after 5 minutes of rest, and the mean of the second and third readings was used for analysis. Body mass index was calculated as weight (in kilograms)/height (in meters squared) using measurements taken while participants wore light clothing without shoes.

Definition of Incident ESRD

The ARIC cohort was linked with the USRDS registry to obtain cases of incident ESRD between baseline (ARIC study visit 2, 1990–1992) through December 31, 2010, as reported to the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on the Medical Evidence Form 2728 within 45 days of RRT initiation. Participants with USRDS-identified ESRD at baseline were excluded from analyses of incident ESRD (n=12).

Definition of Incident CKD

As a secondary outcome, CKD was defined by CKD-related International Classification of Disease diagnostic codes (revisions 9 and 10) for hospitalizations and deaths that occurred from baseline through December 31, 2010, USRDS-identified ESRD, or eGFR decline (defined as eGFRCr<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and at least 25% decline in eGFRCr from baseline). This outcome definition uses both study visit data and intervening hospitalization data in an attempt to mitigate selection bias caused by potential differential loss to follow-up based on kidney disease status. This definition is based on Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes criteria and was previously validated in the ARIC study.2,40 Compared with an outpatient eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the sensitivity was 34.7% and specificity was 96.2% for this diagnostic code CKD definition. Participants with CKD at baseline were excluded from analyses of incident CKD (n=268).

Statistical Analyses

For descriptive purposes, we examined the associations of baseline levels of serum FGF-23 quintiles with demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants using means, medians, SDs, and proportions. We tested for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics across FGF-23 quintiles using ANOVA and chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. In a cross-sectional analysis, pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for FGF-23, other mineral metabolism biomarkers, and eGFR. Because of the non-normal distribution of FGF-23 levels, we used logarithmic transformation and categorized values by quintiles.

Cox proportional regression models were used to assess the association between baseline levels of serum FGF-23 and incident ESRD during follow-up, incorporating time until event. Restricted cubic splines were used to present age, sex, and race-adjusted as well as fully adjusted HRs for ESRD by continuous FGF-23 level with five knots at 24.1, 34.8, 41.9, 50.6, and 72.3 pg/ml corresponding to the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th, and 95th percentiles, respectively, as suggested by Harrell.41 For the splines, FGF-23 levels were truncated at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to visually depict ESRD-free survival probabilities over follow-up time according to FGF-23 quintiles.

To examine the independent association of FGF-23 with incident ESRD, multivariable models were adjusted for several baseline covariates. Model 1 did not include any covariates. Model 2 included basic demographic characteristics (age, sex, and race). Model 3 included all variables in model 2 plus eGFRCr-Cys. Model 4 included kidney disease risk factors (diabetes status, systolic BP, antihypertensive medication use, HDL cholesterol, body mass index, C-reactive protein, β2-microglobulin) in addition to all the variables in model 3. Finally, model 5 included all variables in model 4 plus markers of mineral metabolism (phosphate, parathyroid hormone, calcium). The quintile with the lowest baseline FGF-23 level was used as the reference group. To test for linear trend, the median FGF-23 value in each quintile was treated as a continuous variable in regression models. In a continuous analysis, ESRD risk was expressed per 10-pg/ml FGF-23 increment. To determine whether serum phosphate was independently associated with ESRD, the same modeling approach described above was utilized, except FGF-23 was the last covariate added to the multivariable models. Phosphate was modeled as a linear spline with one knot at 3.5 mg/dl. The linear spline was used to better characterize the shape of the association since ESRD risk changed at phosphate level of 3.5 mg/dl.

In a sensitivity analysis, the available data on the urine albumin/creatinine ratio (measured at study visit 4, 1996–1998) was included as a covariate in regression models, and the observation period was limited to follow-up time after measurement of the urine albumin/creatinine ratio among participants without ESRD at study visit 4 (n=10,642; 79.1%). The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals and by assessing the statistical significance of FGF-23 quintiles and ln(follow-up time). Interaction terms were tested in all of the main regression models to assess effect modification by age, sex, race, and eGFR on the association between FGF-23 and kidney disease outcomes. Competing risk regression models were used to examine the association between FGF-23 and kidney disease outcomes, accounting for the competing risk of death before kidney events.42 All tests were two-sided and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using Stata software (version 12; StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Roche reagents were provided gratis by the Roche Diagnostics Corporation. Roche Diagnostices had no involvement in the design, analysis, or reporting of results.

The ARIC study is conducted as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C). Measurement of the main analytes in this article was supported by grants from the NHLBI (R01-HL103706 to P.L.) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (R01-DK089174 to E.S.). C.M.R. is supported in part by an NHLBI cardiovascular epidemiology training grant (T32-HL007024). This study was partially supported by grants from the NIDDK (U01-DK085649, U01-DK085673, U01-DK085660, U01-DK085688, U01-DK085651, and U01-DK085689 to the Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarkers Consortium).

The Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarkers Consortium Investigators are listed online (www.ckdbiomarkersconsortium.org). The following individuals contributed to this article: Shawn Ballard, Charles Girard, and Krista Whitehead (University of Pennsylvania, Coordinating Center); and John W. Kusek (NIDDK).

Some of the data reported here were supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology, held November 5–10, 2013, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “The Biomarker Niche for Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Testing in CKD,” on pages 7–9.

References

- 1.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, Johnson RJ, Köttgen A, Levey AS, Levin A: Evolving importance of kidney disease: From subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 382: 158–169, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, James MT, Klarenbach S, Quinn RR, Wiebe N, Tonelli M, Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 303: 423–429, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El Nahas M, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, Kasiske BL, Eckardt KU: The definition, classification, and prognosis of chronic kidney disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference report. Kidney Int 80: 17–28, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf M: Forging forward with 10 burning questions on FGF23 in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1427–1435, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf M: Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 82: 737–747, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T: FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res 19: 429–435, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominguez JR, Shlipak MG, Whooley MA, Ix JH: Fractional excretion of phosphorus modifies the association between fibroblast growth factor-23 and outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 647–654, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, Hu MC, Sloan A, Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Aguillon-Prada R, Lincoln J, Hare JM, Mundel P, Morales A, Scialla J, Fischer M, Soliman EZ, Chen J, Go AS, Rosas SE, Nessel L, Townsend RR, Feldman HI, St John Sutton M, Ojo A, Gadegbeku C, Di Marco GS, Reuter S, Kentrup D, Tiemann K, Brand M, Hill JA, Moe OW, Kuro-O M, Kusek JW, Keane MG, Wolf M: FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 121: 4393–4408, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Jüppner H, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 359: 584–592, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, Xie D, Anderson AH, Scialla J, Wahl P, Gutiérrez OM, Steigerwalt S, He J, Schwartz S, Lo J, Ojo A, Sondheimer J, Hsu CY, Lash J, Leonard M, Kusek JW, Feldman HI, Wolf M, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group : Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 305: 2432–2439, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ix JH, Katz R, Kestenbaum BR, de Boer IH, Chonchol M, Mukamal KJ, Rifkin D, Siscovick DS, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG: Fibroblast growth factor-23 and death, heart failure, and cardiovascular events in community-living individuals: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 200–207, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker BD, Schurgers LJ, Brandenburg VM, Christenson RH, Vermeer C, Ketteler M, Shlipak MG, Whooley MA, Ix JH: The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Ann Intern Med 152: 640–648, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scialla JJ, Lau WL, Reilly MP, Isakova T, Yang HY, Crouthamel MH, Chavkin NW, Rahman M, Wahl P, Amaral AP, Hamano T, Master SR, Nessel L, Chai B, Xie D, Kallem RR, Chen J, Lash JP, Kusek JW, Budoff MJ, Giachelli CM, Wolf M, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators : Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney Int 83: 1159–1168, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor EN, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC: Plasma fibroblast growth factor 23, parathyroid hormone, phosphorus, and risk of coronary heart disease. Am Heart J 161: 956–962, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fliser D, Kollerits B, Neyer U, Ankerst DP, Lhotta K, Lingenhel A, Ritz E, Kronenberg F, Kuen E, König P, Kraatz G, Mann JF, Müller GA, Köhler H, Riegler P, MMKD Study Group : Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: The Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2600–2608, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scialla JJ, Astor BC, Isakova T, Xie H, Appel LJ, Wolf M: Mineral metabolites and CKD progression in African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 125–135, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada T, Urakawa I, Isakova T, Yamazaki Y, Epstein M, Wesseling-Perry K, Wolf M, Salusky IB, Jüppner H: Circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 in patients with end-stage renal disease treated by peritoneal dialysis is intact and biologically active. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 578–585, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semba RD, Fink JC, Sun K, Cappola AR, Dalal M, Crasto C, Ferrucci L, Fried LP: Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 and risk of incident chronic kidney disease in older community-dwelling women. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 85–91, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stubbs JR, Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, Wang Y, Yao X, Quarles LD: Role of hyperphosphatemia and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in vascular calcification and mortality in fibroblastic growth factor 23 null mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2116–2124, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haut LL, Alfrey AC, Guggenheim S, Buddington B, Schrier N: Renal toxicity of phosphate in rats. Kidney Int 17: 722–731, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfrey AC: The role of abnormal phosphorus metabolism in the progression of chronic kidney disease and metastatic calcification. Kidney Int Suppl 90: S13–S17, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández-Juárez G, Luño J, Barrio V, de Vinuesa SG, Praga M, Goicoechea M, Lahera V, Casas L, Oliva J, PRONEDI Study Group : 25 (OH) vitamin D levels and renal disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy and blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1870–1876, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panichi V, Migliori M, Taccola D, Filippi C, De Nisco L, Giovannini L, Palla R, Tetta C, Camussi G: Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 in experimental mesangial proliferative nephritis in rats. Kidney Int 60: 87–95, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aschenbrenner JK, Sollinger HW, Becker BN, Hullett DA: 1,25-(OH(2))D(3) alters the transforming growth factor β signaling pathway in renal tissue. J Surg Res 100: 171–175, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migliori M, Giovannini L, Panichi V, Filippi C, Taccola D, Origlia N, Mannari C, Camussi G: Treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 preserves glomerular slit diaphragm-associated protein expression in experimental glomerulonephritis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 18: 779–790, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makibayashi K, Tatematsu M, Hirata M, Fukushima N, Kusano K, Ohashi S, Abe H, Kuze K, Fukatsu A, Kita T, Doi T: A vitamin D analog ameliorates glomerular injury on rat glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol 158: 1733–1741, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakanishi S, Kazama JJ, Nii-Kono T, Omori K, Yamashita T, Fukumoto S, Gejyo F, Shigematsu T, Fukagawa M: Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 levels predict the future refractory hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients. Kidney Int 67: 1171–1178, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutierrez O, Isakova T, Rhee E, Shah A, Holmes J, Collerone G, Jüppner H, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor-23 mitigates hyperphosphatemia but accentuates calcitriol deficiency in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2205–2215, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1370–1378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith ER, Cai MM, McMahon LP, Holt SG: Biological variability of plasma intact and C-terminal FGF23 measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 3357–3365, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith ER, Ford ML, Tomlinson LA, Weaving G, Rocks BF, Rajkumar C, Holt SG: Instability of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23): Implications for clinical studies. Clin Chim Acta 412: 1008–1011, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith ER, McMahon LP, Holt SG: Method-specific differences in plasma fibroblast growth factor 23 measurement using four commercial ELISAs. Clin Chem Lab Med 51: 1971–1981, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, Tighiouart H, Djurdjev O, Naimark D, Levin A, Levey AS: A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 305: 1553–1559, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The ARIC Investigators : The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol 129: 687–702, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ: Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem 28: 1379–1388, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lustgarten JA, Wenk RE: Simple, rapid, kinetic method for serum creatinine measurement. Clin Chem 18: 1419–1422, 1972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS, CKD-EPI Investigators : Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med 367: 20–29, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grams ME, Rebholz CM, McMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Selvin E, Wruck L, Coresh J: Identification of incident CKD stage 3 in research studies [published online ahead of print April 10, 2014]. Am J Kidney Dis 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrell FE: Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis, New York, Springer, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fine JP, Gray RJ: A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509, 1999 [Google Scholar]