Abstract

Silicon dioxide (SiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles are widely used in various applications, raising issues regarding the possible adverse effects of these metal oxide nanoparticles on human cells. In this study, we determined the cytotoxic effects of differently charged SiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles, with mean sizes of either 100 or 20 nm, on the U373MG human glioblastoma cell line. The overall cytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles against U373MG cells was significantly higher than that of SiO2 nanoparticles. Neither the size nor the surface charge of the ZnO nanoparticles affected their cytotoxicity against U373MG cells. The 20 nm SiO2 nanoparticles were more toxic than the 100 nm nanoparticles against U373MG cells, but the surface charge had little or no effect on their cytotoxicity. Both SiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles activated caspase-3 and induced DNA fragmentation in U373MG cells, suggesting the induction of apoptosis. Thus, SiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles appear to exert cytotoxic effects against U373MG cells, possibly via apoptosis.

Keyword: apoptosis

Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) are objects with at least one dimension less than 100 nm.1 Many NPs offer unique and beneficial properties, and they have been widely used in medical, pharmaceutical, food, cosmetics, electronics, and other industries (reviewed in Uskokovic).2 Silicon dioxide (SiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs have photocatalytic activities and are commonly used in various consumer products (eg, cosmetics) and biomedical applications (eg, drug delivery and theranostics) (reviewed in Fan and Lu3 and Fine et al4).

Given their widespread use, humans are constantly exposed to SiO2 and ZnO NPs, which can enter the body via ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption.5 NPs may interact with tissue macromolecules and adversely affect cellular physiology.6–10 Numerous studies have investigated the cytotoxic effects of SiO2 and ZnO NPs,11–19 but many controversies remain due to the physical and chemical properties of these NPs.

Furthermore, we do not yet fully understand the underlying cell-death mechanisms induced by SiO2 and ZnO NPs. For example, SiO2 and ZnO NPs reportedly trigger the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inducing the p53 pathway to activate the caspase cascade.20–23 Both SiO2 and ZnO NPs were shown to activate the initiator caspase-9 and the executioner caspase-3 in human lung epithelial cells and dermal fibroblasts.20–23 However, a recent study found that ZnO NP-mediated apoptosis was not related to ROS generation or the p53 pathway.24 Thus, the cell-death pathways mediated by SiO2 and ZnO NPs are still the subject of some debate.

In this study, we investigated the cytotoxic effects of SiO2 and ZnO NPs on the U373MG human glioblastoma cell line. Since cytotoxic potentials may be affected by the physical and chemical properties of NPs, such as their sizes and surface charges, we selected SiO2 and ZnO NPs of different sizes (100 nm and 20 nm) and surface charges and examined their cytotoxic and apoptotic effects on U373MG cells.

Materials and methods

Cells, reagents, and preparation of NPs

The U373MG cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Biowest, Nuaille, France) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowest), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Zinc chloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The 20 and 100 nm ZnO NPs were purchased from Sumitomo Osaka Cement Co, Ltd (Lot number 141319) (Tokyo, Japan) and American Elements (Lot number 1871511079-673) (Los Angeles, CA, USA), respectively. The surface charge of the ZnO NPs was modified with citrate (for a negative charge) and L-serine (for a positive charge), as previously reported.25 The 20 and 100 nm SiO2 NPs were purchased from E&B Nanotech Co, Ltd (Ansan-si, South Korea). To reduce their negative charge, the SiO2 NPs were treated with L-arginine (R). Detailed information regarding the characterizations and physicochemical properties of the SiO2 and ZnO NPs can be found in Kim et al.26

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were harvested, fractionated, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as described previously.27 Antibodies to poly-(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and alpha-tubulin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively. Enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and secondary peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were used according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Cell viability and DNA fragmentation assays

Cell viability was determined by using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. DNA fragmentation was determined by using the DeadEnd™ Fluorometric terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) System (Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Nuclei were stained using Vectasheild mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA).

Results

Effect of SiO2 or ZnO NPs on the viability of U373MG human glioblastoma cells

The U373MG cells were treated with various concentrations of SiO2 or ZnO NPs with different sizes and surface charges (ZnOAE100(+), ZnOAE100(−), ZnOSM20(+), ZnOSM20(−), SiO2EN100(R), SiO2EN100(−), SiO2EN20(R), and SiO2EN20(−)). After 24 hours, cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo assay, which determines the presence of live and metabolically active cells by measuring adenosine triphosphate (Figure 1). Treatment with 6 mg/mL of SiO2EN100(R) and SiO2EN100(−) reduced the viability of U373MG cells by 68% and 65%, respectively (Figure 1A and B). Interestingly, the 20 nm SiO2 NPs were more toxic to U373MG cells than 100 nm SiO2 NPs. Treatment with 0.6 and 0.9 mg/mL of SiO2EN20(R) reduced the viability of U373MG cells by 90% and 98%, respectively (Figure 1C). Similarly, treatment with 0.6 and 0.8 mg/mL of SiO2EN20(−) reduced the viability of U373MG cells by 23% and 96%, respectively (Figure 1D). The cytotoxicity of SiO2 NPs was not cell-type specific as we observed similar levels of cytotoxicity against human dermal fibroblast and HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cells (data not shown). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration values for the cytotoxicity of SiO2EN100(R), SiO2EN100(−), SiO2EN20(R) and SiO2EN20(−) against U373MG cells at 24 hours after treatment were 4.36, 4.93, 0.41, and 0.68 mg/mL, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of SiO2 NPs on the viability of U373MG cells.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with various concentration of (A) SiO2EN100(R), (B) SiO2EN100(−), (C) SiO2EN20(R), or (D) SiO2EN20(−) NPs. At 24 hours after treatment, cell viability was determined with the CellTiter-Glo assay. To calculate the relative luciferase activities, the luciferase activities at 0 hours after treatment were set to 100%. The data shown here represent the results from three independent experiments.

Abbreviations: NPs, nanoparticles; RLU, relative luminescence units; SiO2, silicon dioxide.

Table 1.

The IC50 values for the cytotoxicity of SiO2 or ZnO NPs against U373MG cells at 24 hours

| NPs | IC50(μg/mL) |

|---|---|

| ZnOAE100(+) | 19.67±0.78 |

| ZnOAE100(−) | 20.47±0.84 |

| ZnOSM20(+) | 16.82±0.42 |

| ZnOSM20(−) | 19.67±1.85 |

| SiO2EN100(R) | 4,360.0±0.10 |

| SiO2EN100(−) | 4,930.0±0.16 |

| SiO2EN20(R) | 410.0±0.01 |

| SiO2EN20(−) | 680.0±0.03 |

Abbreviations: IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; NPs, nanoparticles; SiO2, silicon dioxide; ZnO, zinc oxide.

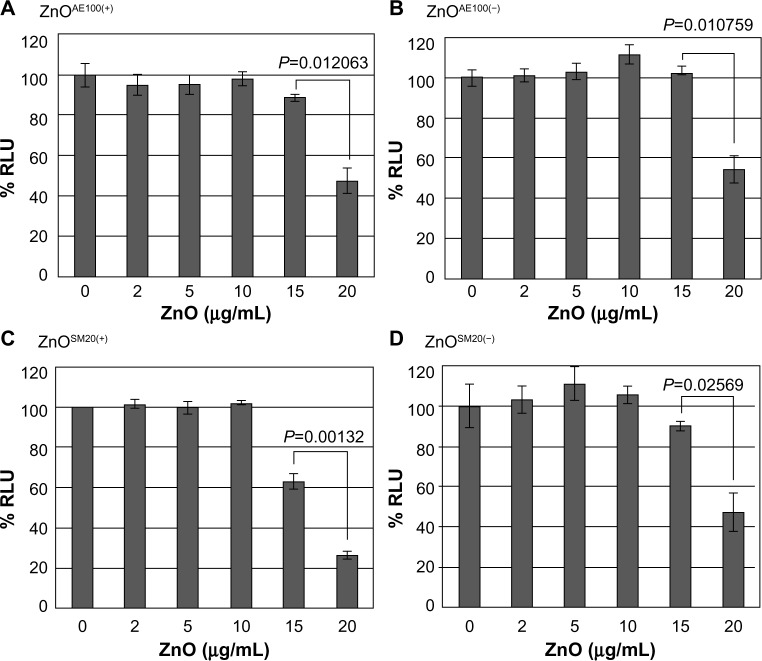

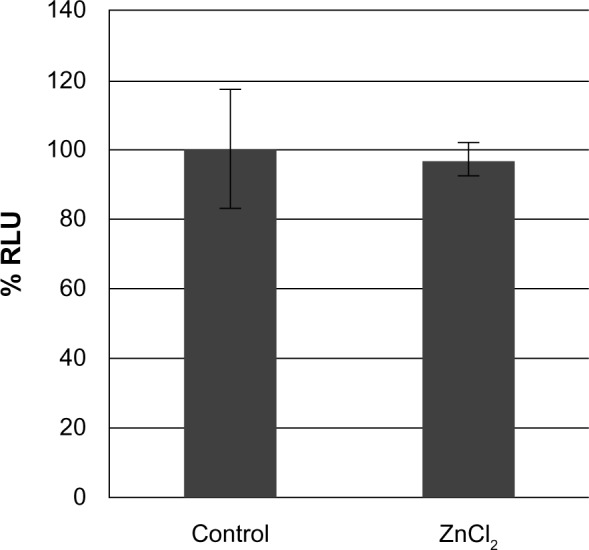

Compared to the SiO2 NPs, the ZnO NPs were significantly more toxic to U373MG cells as treatment with 20 μg/mL of ZnOAE100(+), ZnOAE100(−), ZnOSM20(+), and ZnOSM20(−) for 24 hours reduced the viability of U373MG cells by 53%, 47%, 74%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). The half- maximal inhibitory concentration values for the cytotoxicity of ZnOAE100(+), ZnOAE100(−), ZnOSM20(+), and ZnOSM20(−) on U373MG cells at 24 hours after treatment were 19.67, 20.47, 16.82, and 19.67 μg/mL, respectively (Table 1). Since treatment with 20 μg/mL of zinc chloride exhibited no cytotoxic effect against U373MG cells, the observed cytotoxicity appeared to have been due to the effect of the ZnO NPs (rather than Zn2+) on U373MG cells (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The effect of ZnO NPs on the viability of U373MG cells.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, or 20 μg/mL of (A) ZnOAE100(+), (B) ZnOAE100(−), (C) ZnOSM20(+), or (D) ZnOSM20(−) NPs. At 24 hours after treatment, cell viability was determined with the CellTiter-Glo assay. To calculate the relative luciferase activities, the luciferase activities at 0 hours after treatment were set to 100%. The data shown here represent the results from three independent experiments. Significant differences between samples were determined by the P-value of a two-sample t-test (P<0.05).

Abbreviations: NPs, nanoparticles; RLU, relative luminescence units; ZnO, zinc oxide.

Figure 3.

The effect of non-nano ZnCl2 on the viability of U373MG cells.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with or without 20 μg/mL ZnCl2. At 24 hours after treatment, cell viability was determined with the Celltiter-Glo assay. To calculate the relative luciferase activities, the luciferase activities of mock-treated cells were set to 100%. The data shown here represent the results from three independent experiments.

Abbreviations: RLU, relative light unit; ZnCl2, zinc chloride.

Taken together, these results indicate that the ZnO NPs were more toxic than SiO2 NPs against U373MG cells. Furthermore, the 20 nm SiO2 NPs were more toxic than the 100 nm NPs, whereas the cytotoxicity of ZnO NPs was not affected by their size or surface charge in our experimental systems.

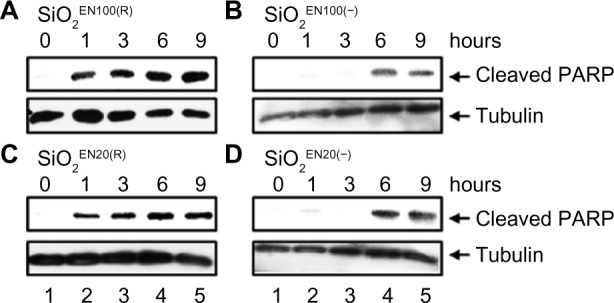

Effect of SiO2 or ZnO NPs on caspase-3 activation

To determine whether SiO2 or ZnO NPs induce apoptosis, U373MG cells were treated with the above-described SiO2 or ZnO NPs, and caspase-3 activation was assessed by determining the proteolytic cleavage of PARP (from the native 116 kDa to 89 kDa) at 0, 1, 3, 6, and 9 hours after treatment. The treatment of U373MG cells with SiO2 NPs at the concentrations shown to reduce cell viability by 85% to 90% was found to rapidly induce PARP cleavage at 1 hour after treatment (Figure 4; compare lane 2 with lane 1). ZnOAE100(−) and ZnOSM20(−) also rapidly induced PARP cleavage in U373MG cells at 1 hour after treatment (Figure 5A and B; compare lane 2 with lane 1), whereas ZnOAE100(+) and ZnOSM20(+) induced PARP cleavage at later time points at 9 and 6 hour, respectively (Figure 5C and D; compare lane 2 with lane 1). These data indicate that both SiO2 and ZnO NPs induce caspase-3 activation, further suggesting that they both induce apoptosis.

Figure 4.

The effect of SiO2 NPs on caspase activation.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with 9 mg/mL of (A) SiO2EN100(R) or (B) SiO2EN100(−) NPs, or 0.8 mg/mL of (C) SiO2EN20(R) or (D) SiO2EN20(−) NPs. At 0, 1, 3, 6 and 9 hours after treatment, PARP cleavage was determined by Western blot analysis.

Abbreviations: NPs, nanoparticles; PARP, poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase; SiO2, silicon dioxide.

Figure 5.

The effect of ZnO nanoparticles on caspase activation.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with 20 μg/mL of (A) ZnOAE100(−), (B) ZnOSM20(−), (C) ZnOAE100(+), or (D) ZnOSM20(+) NPs. At 0, 1, 3, 6, 9 hours after treatment, PARP cleavage was determined by Western blot analysis.

Abbreviations: NPs, nanoparticles; PARP, poly-(adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase; ZnO, zinc oxide.

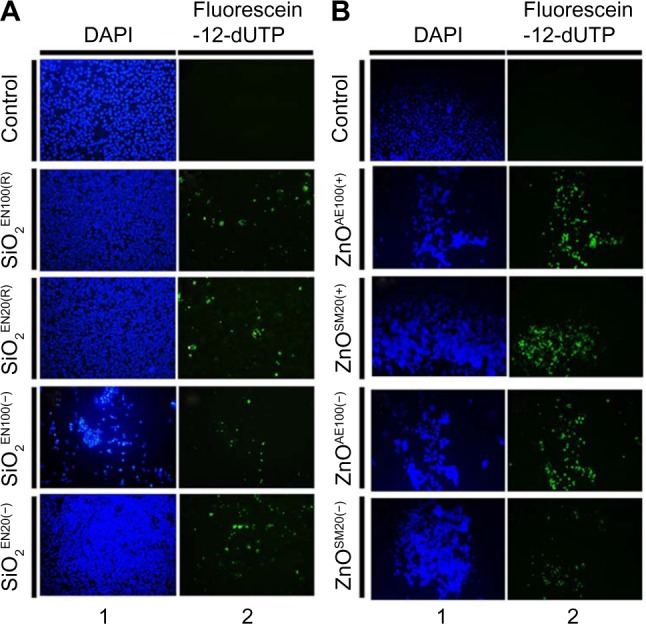

Effect of SiO2 or ZnO NPs on chromosomal DNA fragmentation and damage

To further assess the apoptotic effects of SiO2 or ZnO NPs, U373MG cells were treated with the above-described NPs for 6 hours, and chromosomal DNA fragmentation was determined using a TUNEL assay. As expected, SiO2 NPs and ZnO NPs induced chromosomal DNA fragmentation in U373MG cells (Figure 6). At 6 hours after treatment with SiO2EN100(R), SiO2EN100(−), SiO2EN20(R), and SiO2EN20(−), 11.7%, 12.9%, 10.8%, and 10.1% of the cells were found to be TUNEL positive (Figure 6A). Compared to the SiO2 NPs, the ZnO NPs were more potent in inducing chromosomal DNA fragmentation as 42.7%, 60.4%, 42.8%, and 19.5% of the cells treated with ZnOAE100(+), ZnOAE100(−), ZnOSM20(+), and ZnOSM20(−), respectively, were found to be TUNEL positive (Figure 6B). These data suggest that the ZnO NPs may be more effective at inducing chromosomal DNA fragmentation in these cells (Figure 6B). In addition to the TUNEL assay, the comet assay was employed to examine DNA damage in SiO2 or ZnO NP-treated cells. Consistent with the TUNEL data, both SiO2 and ZnO NPs induced DNA damage in U373MG cells (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that both SiO2 and ZnO NPs reduce the viability of U373MG cells by inducing apoptosis, and further suggest that ZnO NPs may be more effective than SiO2 NPs for inducing apoptosis in U373MG cells.

Figure 6.

The effect of SiO2 or ZnO NPs on DNA fragmentation.

Notes: U373MG cells were treated with (A) SiO2 or (B) ZnO NPs with different sizes and surface charges at the concentrations described above. At 6 hours after treatment, fragmented DNA was labeled with fluorescein-12-UTP (green) and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining (blue).

Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; NPs, nanoparticles; SiO2, silicon dioxide; ZnO, zinc oxide; UTP, uridine triphosphate.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the cytotoxic effects of SiO2 and ZnO NPs with two different sizes (20 and 100 nm) and charges (positive and negative) against the U373MG human glioblastoma cell line. The SiO2 and ZnO NPs both reduced the viability of U373MG cells at 24 hours after treatment. The ZnOSM20(+), ZnOSM20(−), ZnOAE100(+), and ZnOAE100(−) NPs were 24-, 34-, 222-, and 241-fold more toxic to U373MG cells than their corresponding SiO2 NP counterparts. These differences in the cytotoxicities of the SiO2 and ZnO NPs may reflect differences in solubility, dissolution rate in the media, protein interactions, ROS generation, and/or the ability to activate the intrinsic apoptotic and/or necrotic pathways.

Other studies have indicated that both size and surface charge can influence the cytotoxicity of SiO2 and ZnO NPs.28–31 Consistent with these studies, we observed that particle size affected the cytotoxicity of SiO2EN20(R) and SiO2EN20(−) NPs, which were, respectively, eleven- and sevenfold more toxic than 100 nm counterparts against U373MG cells. Smaller NPs may be more effective at entering cells and organelles (eg, mitochondria), allowing them more opportunity to induce oxidative stress and apoptosis.14,31–33 In contrast to the previous reports, however, we found that the surface charge of SiO2 NPs had almost no effect on their cytotoxicity against U373MG cells. Although SiO2EN100(R) and SiO2EN20(R) NPs were slightly more toxic than SiO2EN100(−) and SiO2EN20(−), respectively, these differences were not significant. Also, inconsistent with the previous reports, we found that the cytotoxicity of ZnO NPs against U373MG cells was unaffected by their size and surface charge. Future work will be needed to examine these apparent discrepancies.

Treatment of U373MG cells with SiO2 NPs was found to rapidly activate caspase-3 and induce apoptosis within 1 hour. Treatment with ZnOAE100(−) and ZnOSM20(−) NPs also activated caspase-3 by 1 hour after treatment, whereas ZnOAE100(+) and ZnOSM20(+) activated caspase-3 later (9 and 6 hours after treatment, respectively). Previous reports showed that SiO2 and ZnO NPs may induce the intrinsic pathway for apoptosis via ROS-mediated p53 activation.20–23 ROS-induced DNA damage activates p53, which triggers apoptosis by transactivating proapoptotic genes and activating other transcription-independent mechanisms.34 However, Wilhelmi et al reported that ZnO NPs induce necrosis and apoptosis in macrophages via ROS- and p53-independent pathway.24 Consistent with the latter study, we found that both SiO2 and ZnO NPs induced apoptosis in U373MG cells, which express mutant p53. Other authors have suggested that, in addition to the ROS-mediated p53 activation pathway, SiO2 and ZnO NPs may activate the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and/or c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathways to transactivate proapoptotic genes and induce apoptosis.23,35

Since DNA damage induces the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint to arrest the cell cycle,36 it is not surprising that silica NPs induce cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase.37 More specifically, they induce the G2/M DNA damage checkpoint via the activation of Chk1, which phosphorylates p53.37,38 Since Cdk2 has been reported to play an important role in p53-independent G2/M checkpoint control,39 we speculate that SiO2 and ZnO NPs may arrest the cell cycle at the G2/M phase in U373MG cells, possibly via a Cdk2-dependent pathway. In addition to apoptosis, SiO2 and ZnO NPs may induce necrotic cell death in U373MG cells. Thus, further studies are needed to examine how SiO2 and ZnO NPs induce apoptotic and/or necrotic cell death in human cell lines.

Conclusion

We herein investigated the cytotoxic effects of SiO2 and ZnO NPs with different sizes and surface charges on the human glioblastoma cell line, U373MG. The overall cytotoxicity of the ZnO NPs was significantly higher than that of the SiO2 NPs against U373MG cells. The cytotoxicity of the SiO2 NPs was affected by the particle size, but not the surface charge, in our system, with the smaller SiO2 NPs showing a higher cytotoxicity. In contrast, changes in the size and surface charge of the ZnO NPs had little or no effect on their cytotoxicity against U373MG cells. Both SiO2 and ZnO NPs were found to activate caspase-3 and induce DNA fragmentation in our system. Thus, we report that the tested SiO2 and ZnO NPs exhibited cytotoxic effects against U373MG cells, at least partly via the induction of apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (10182MFDS991) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2010–2011.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ma H, Williams PL, Diamond SA. Ecotoxicity of manufactured ZnO nanoparticles – a review. Environ Pollut. 2013;172:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uskoković V. Entering the era of nanoscience: time to be so small. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2013;9(9):1441–1470. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2013.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan Z, Lu JG. Zinc oxide nanostructures: synthesis and properties. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2005;5(10):1561–1573. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2005.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fine D, Grattoni A, Goodall R, et al. Silicon micro- and nanofabrication for medicine. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2(5):632–666. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasir A. Nanotechnology and dermatology: part II – risks of nanotechnology. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(5):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng ZJ, Mortimer G, Schiller T, Musumeci A, Martin D, Minchin RF. Differential plasma protein binding to metal oxide nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2009;20(45):455101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/45/455101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundqvist M, Stigler J, Cedervall T, et al. The evolution of the protein corona around nanoparticles: a test study. ACS Nano. 2011;5(9):7503–7509. doi: 10.1021/nn202458g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okoturo-Evans O, Dybowska A, Valsami-Jones E, et al. Elucidation of toxicity pathways in lung epithelial cells induced by silicon dioxide nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekkapongpisit M, Giovia A, Follo C, Caputo G, Isidoro C. Biocompatibility, endocytosis, and intracellular trafficking of mesoporous silica and polystyrene nanoparticles in ovarian cancer cells: effects of size and surface charge groups. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:4147–4158. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S33803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Pie JE, Kim YR, Lee HR, Son SW, Kim MK. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on gene expression profile in human keratinocytes. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2012;8(2):113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer AT, Strozyk EA, Gorzelanny C, et al. Cytotoxicity of silica nanoparticles through exocytosis of von Willebrand factor and necrotic cell death in primary human endothelial cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8385–8393. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabolli V, Thomassen LC, Princen C, et al. Influence of size, surface area and microporosity on the in vitro cytotoxic activity of amorphous silica nanoparticles in different cell types. Nanotoxicology. 2010;4(3):307–318. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.482749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbalan JJ, Medina C, Jacoby A, Malinski T, Radomski MW. Amorphous silica nanoparticles trigger nitric oxide/peroxynitrite imbalance in human endothelial cells: inflammatory and cytotoxic effects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:2821–2835. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, et al. Comparison of the mechanism of toxicity of zinc oxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles based on dissolution and oxidative stress properties. ACS Nano. 2008;2(10):2121–2134. doi: 10.1021/nn800511k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma V, Anderson D, Dhawan A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and genotoxicity in human liver cells (HepG2) J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2011;7(1):98–99. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2011.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma V, Singh P, Pandey AK, Dhawan A. Induction of oxidative stress, DNA damage and apoptosis in mouse liver after sub-acute oral exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mutat Res. 2012;745(1–2):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma V, Anderson D, Dhawan A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and ROS-triggered mitochondria mediated apoptosis in human liver cells (HepG2) Apoptosis. 2012;17(8):852–870. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho WS, Duffin R, Poland CA, et al. Metal oxide nanoparticles induce unique inflammatory footprints in the lung: important implications for nanoparticle testing. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1699–1706. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kermanizadeh A, Pojana G, Gaiser BK, et al. In vitro assessment of engineered nanomaterials using a hepatocyte cell line: cytotoxicity, pro-inflammatory cytokines and functional markers. Nanotoxicology. 2013;7(3):301–313. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.653416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z, Chou L, Sun J. Effects of SiO2 nanoparticles on HFL-I activating ROS-mediated apoptosis via p53 pathway. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32(5):358–364. doi: 10.1002/jat.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahamed M. Silica nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative stress and apoptosis in cultured A431 and A549 cells. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2013;32(2):186–195. doi: 10.1177/0960327112459206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahamed M, Akhtar MJ, Raja M, et al. ZnO nanorod-induced apoptosis in human alveolar adenocarcinoma cells via p53, survivin and bax/bcl-2 pathways: role of oxidative stress. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(6):904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer K, Rajanahalli P, Ahamed M, Rowe JJ, Hong Y. ZnO nanoparticles induce apoptosis in human dermal fibroblasts via p53 and p38 pathways. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25(8):1721–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilhelmi V, Fischer U, Weighardt H, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce necrosis and apoptosis in macrophages in a p47phox- and Nrf2-independent manner. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K-M, Kim T-H, Kim H-M, et al. Colloidal behaviors of ZnO nanoparticles in various aqueous media. Toxicol Environ Health Sci. 2012;4(2):121–131. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KM, Choi MH, Lee JK, et al. Physicochemical properties of surface charge-modified ZnO nanomaterials with different particle sizes. 2014 doi: 10.2147/IJN.S57923. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song YJ, Stinski MF. Inhibition of cell division by the human cytomegalovirus IE86 protein: role of the p53 pathway or cyclin-dependent kinase 1/cyclin B1. J Virol. 2005;79(4):2597–2603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2597-2603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park YH, Bae HC, Jang Y, et al. Effect of the size and surface charge of silica nanoparticles on cutaneous toxicity. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2013;9(1):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greish K, Thiagarajan G, Herd H, et al. Size and surface charge significantly influence the toxicity of silica and dendritic nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2012;6(7):713–723. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.604442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pujalté I, Passagne I, Brouillaud B, et al. Cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by different metallic nanoparticles on human kidney cells. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malvindi MA, Brunetti V, Vecchio G, Galeone A, Cingolani R, Pompa PP. SiO2 nanoparticles biocompatibility and their potential for gene delivery and silencing. Nanoscale. 2012;4(2):486–495. doi: 10.1039/c1nr11269d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae HC, Ryu HJ, Jeong SH, et al. Oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by ZnO nanoparticles in HaCaT cells. Mol Cell Toxicol. 2011;7(4):333–337. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao IL, Huang YJ. Effects of various physicochemical characteristics on the toxicities of ZnO and TiO nanoparticles toward human lung epithelial cells. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409(7):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Speidel D. Transcription-independent p53 apoptosis: an alternative route to death. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNamee LM, Brodsky MH. p53-independent apoptosis limits DNA damage-induced aneuploidy. Genetics. 2009;182(2):423–435. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.102327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cuddihy AR, O’Connell MJ. Cell-cycle responses to DNA damage in G2. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;222:99–140. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)22013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan J, Yu Y, Li Y, Zhou X, Huang P, Sun Z. Toxic effect of silica nanoparticles on endothelial cells through DNA damage response via Chk1-dependent G2/M checkpoint. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ou YH, Chung PH, Sun TP, Shieh SY. p53 C-terminal phosphorylation by CHK1 and CHK2 participates in the regulation of DNA-damage- induced C-terminal acetylation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(4):1684–1695. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung JH, Bunz F. Cdk2 is required for p53-independent G2/M checkpoint control. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(2):e1000863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]