Abstract

Background

Theileria and Anaplasma are especially important emerging tick-borne pathogens of animals and humans. Molecular surveys and identification of the infectious agents in Mongolian gazelle, Procapra gutturosa are not only crucial for the species’ preservation, but also provide valuable information on parasite and bacterial epidemiology.

Findings

A molecular surveillance study was undertaken to assess the prevalence of Theileria spp. and Anaplasma spp. in P. gutturosa by PCR in China. Theileria luwenshuni, A. bovis, A. phagocytophilum, and A. ovis were frequently found in P. gutturosa in China, at a prevalence of 97.8%, 78.3%, 65.2%, and 52.2%, respectively. The prevalence of each pathogens in the tick Haemaphysalis longicornis was 80.0%, 66.7%, 76.7%, and 0%, respectively, and in the tick Dermacentor niveus was 88.2%, 35.3%, 88.2%, and 58.5%, respectively. No other Theileria or Anaplasma species was found in these samples. Rickettsia raoultii was detected for the first time in P. gutturosa in China.

Conclusions

Our results extend our understanding of the epidemiology of theileriosis and anaplasmosis in P. gutturosa, and will facilitate the implementation of measures to control these tick-borne diseases in China.

Keywords: Theileria, Anaplasma, Detection, Procapra gutturosa, PCR, China

Findings

Background

Theileria is mainly transmitted by tick vectors and cause heavy economic losses to the livestock industry. The family Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales was reclassified in 2001, and includes several genera, including Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Neorickettsia, and Wolbachia. Of them, the genera Anaplasma and Ehrlichia are especially important as emerging tick-borne pathogens in both humans and animals [1]. Anaplasma phagocytophilum is the causative agent of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, an extremely dangerous disease associated with high mortality rates in humans [2-4]. Other Anaplasma spp., such as A. bovis, A. ovis, A. marginale, and A. centrale, infect the erythrocytes and other cells of ruminants [3,4]. Anaplasmosis is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas, but is also frequently reported in temperate regions. Six or seven Anaplasma species have been reported in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia [5-11], and some have also been reported in sheep, goats, and cattle throughout China [9,12,13].

The detection and isolation of Theileria and Anaplasma require specialized laboratories staffed by technicians with a high degree of expertise, primarily because the species’ life cycles are intracellular. Several sensitive molecular tools, such as PCR, have been used to detect and identify Theileria and Anaplasma species in both hosts and vectors [10-17].

The Mongolian gazelle, an endemic ungulate species designated a threatened species by the World Conservation Union, is facing human and livestock disturbances of varying intensity in northern China. Although several studies have demonstrated that various Theileria, Babesia, Ehrlichia, and Anaplasma species circulate among sheep, goats, cattle, cervids, and humans in China, almost no data are available on the possible role of P. gutturosa as a host organism. The aim of this study was to detect and identify Theileria and Anaplasma spp. in P. gutturosa, a potential natural host of animal theileriosis and anaplasmosis in China.

Methods

Sample collection

The region investigated in China is located at latitudes 35°03′–35°55′ north and longitudes 105°37′–108°08′ east. The study was performed in April 2014. A total of 92 blood samples were collected randomly from P. gutturosa, and 242 ticks were collected from both P. gutturosa and grass in its environment. Of them, 30 unfed adult ticks were collected directly from grass in the gazelles’ environment; 212 engorged nymph ticks collected from P. gutturosa were kept at 28°C and 80-90% relative humidity during molt, until nymph ticks were molted into adult ticks. All of adults were identified with Teng’s methods [18]. Blood smears were prepared from the ear blood of every P. gutturosa individual. During the blood collection process, cases of suspected theileriosis or anaplasmosis were investigated. Theileriosis and/or anaplasmosis should be suspected in tick-infested animals with fever, enlarged lymph nodes (theileriosis only), anemia, and jaundice.

Microscopic analysis of blood smears

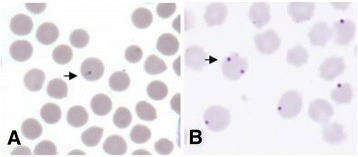

The blood smears were air-dried, fixed in methanol, stained with a 10% solution of Giemsa in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2), and then analyzed microscopically and photographed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theileria (A) and Anaplasma (B) in the blood smears from Mongolian gazelle.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from the 92 whole blood samples and 222 tick samples using a genomic DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA yields were determined with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Molecular detection of Theileria and Anaplasma using species-specific primers

PCR was used to detect and identify Theileria and Anaplasma spp. in P. gutturosa with the species-specific primers shown in Table 1 [10,11,14-17]. The PCR reactions were performed in an automatic DNA thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and the PCR products were used to assess the presence of specific bands indicative of Theileria and Anaplasma.

Table 1.

Sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Pathogen | Target gene | Primers | Final amplicon size (bp) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer name | Oligonucleotide sequences (5’-3’) | ||||

| Anaplasma & Ehrlichia | 16S rRNA | EC9 | TACCTTGTTACGACTT | 1462 | Kawahara et al., 2006 [10] |

| EC12A | TGATCCTGGCTCAGAACGAACG | ||||

| A. bovis | 16S rRNA | AB1f | CTCGTAGCTTGCTATGAGAAC | 551 | Kawahara et al., 2006 [10] |

| AB1r | TCTCCCGGACTCCAGTCTG | ||||

| A. phagocytophilum | 16S rRNA | SSAP2f | GCTGAATGTGGGGATAATTTAT | 641 | Kawahara et al., 2006 [10] |

| SSAP2r | ATGGCTGCTTCCTTTCGGTTA | ||||

| A. marginale | msp4 | Amargmsp4 F | CTGAAGGGGGAGTAATGGG | 344 | Torina et al., 2012 [11] |

| Amargmsp4 R | GGTAATAGCTGCCAGAGATTCC | ||||

| A. ovis | msp4 | Aovismsp4 F | TGAAGGGAGCGGGGTCATGGG | 347 | Torina et al., 2012 [11] |

| Aovismsp4 R | GAGTAATTGCAGCCAGGGACTCT | ||||

| Hemoparasite | 18S rRNA | Primer A | AACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAGT | 1750 | Medlin et al., 1988 [14] |

| Primer B | GATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC | ||||

| Theileria | 18S rRNA | 989 | AGTTTCTGACCTATCAG | 1100 | Allosop et al., 1993 [15] |

| 990 | TTGCCTTAAACTTCCTTG | ||||

| T. luwenshuni | 18S rRNA | Tl310 | GGTAGGGTATTGGCCTACTGA | 340 | Yin et al., 2008 [16] |

| Tl680 | TCATCCGGATAATACAAGT | ||||

| Babesia | 18S rRNA | Babesia F | TGTCTTGAATACTT(C/G)AGCATGGAA | 950 | Ramos et al., 2010 [17] |

| Babesia R | CGACTTCTCCTTTAAGTGATAAC | ||||

The DNA fragments were sequenced by the GenScript Corporation (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Representative sequences of the 18S rDNA/16S rDNA (or msp4) genes of the Theileria and Anaplasma spp. newly identified in this study were deposited in the GenBank database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses

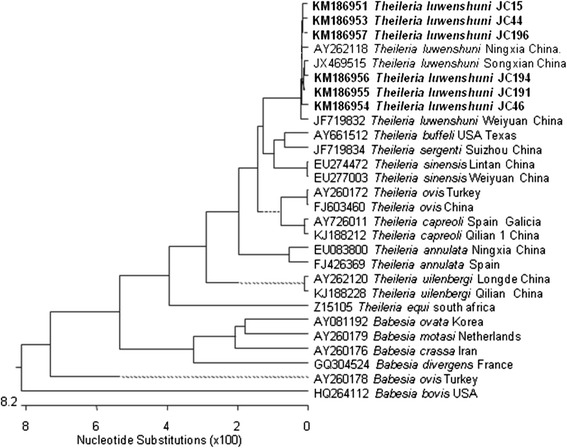

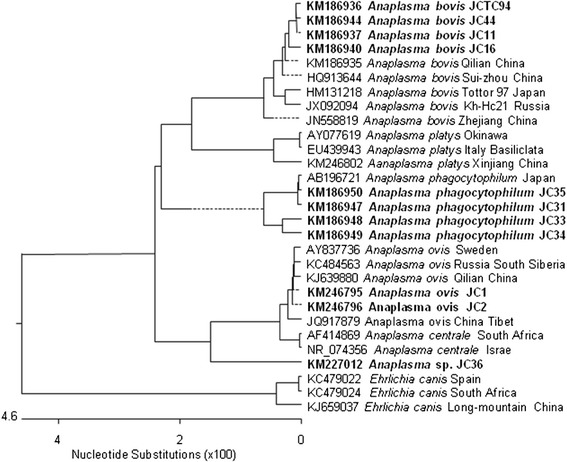

The MegAlign component of the Lasergene® program version 4.01 (DNASTAR) was used to generate multiple sequence alignments with the ClustalW algorithm (www.clustal.org/) and for the phylogenetic analyses using the neighbor-joining method. A phylogenetic tree was constructed (Figure 2) based on the Theileria and Babesia 18S rDNA gene sequences determined in this study, and others obtained from the GenBank database under accession numbers: KM186951–KM186957, AY262118, JX469515, JF719832, AY661512, JF719834, EU274472, EU277003, AY260172, FJ603460, AY726011, KJ188212, EU083800, FJ426369, AY262120, KJ188228, Z15105, AY081192, AY260179, AY260176, GQ304524, AY260178, and HQ264112. Another phylogenetic tree was constructed (Figure 3) based on sequences of the Anaplasma and Ehrlichia 16S RNA genes under the following accession numbers: KM186935–KM186937, KM186940, KM186944, KM186947-KM186950, KM246795, KM246796, KM227012, HQ913644, HM131218, JX092094, JN558819, AY077619, EU439943, KM246802, AB196721, AY837736, KC484563, KJ639880, JQ917879, AF414869, NR_074356, KC479022, KC479024, and KJ659037.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Theileria and Babesia based on 18S rDNA sequences.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Theileria and Babesia based on 16S rDNA sequences.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, CAAS (No. LVRIAEC2013-010). The use of these field samples was approved by the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guideline of China.

Results

Tick identification

In this study, all 242 ticks were collected from P. gutturosa or grass in its environment in north-western China. The identification result showed that the adult ticks were either Haemaphysalis longicornis (n = 130: 86 female; 44 male) or Dermacentor niveus (n = 112: 78 female; 34 male). The whole DNA of 120 H. longicornis ticks and 102 D. niveus ticks was extracted.

Microscopic examination of blood smears

Theileriosis and anaplasmosis was present in 50% of the gazelles tested (46/92). Theileria and Anaplasma infections were observed microscopically in 87.0% (80/92), and 13.0% (12/92) of the blood smears from P. gutturosa individuals, respectively (Figure 1). All infected animals exhibited low levels of parasitemia, with 0.01–6% for Theileria and 0.01–4% for Anaplasma.

PCR detection of Theileria and Anaplasma with species-specific primer sets

PCR analysis revealed that the prevalence of T. luwenshuni, A. bovis, A. phagocytophilum, and A. ovis in P. gutturosa was 97.8%, 78.3%, 65.2%, and 52.2%, respectively. Their prevalence in H. longicornis was 80.0%, 66.7%, 76.7%, and 0%, respectively, and their prevalence in D. niveus was 88.2%, 35.3%, 88.2%, and 58.8%, respectively (Table 2). No Babesia sp. was found in P. gutturosa, H. longicornis, or D. niveus. Only one (4.3%) of the 92 samples from P. gutturosa was positive for R. raoultii.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Theileria and Anaplasma in Procapra gutturosa and ticks in China

| Host | No. of samples | The prevalence of Theileria and Anaplasma in Procapra gutturosa and Ticks by PCR and Microscopic Examination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Microscopic Examination (ME) | By PCR | ||||||

| Theileria spp. | Anaplasma spp. | T. luwenshuni | A. bovis | A. phagocytophilum | A. ovis | ||

| Procapra gutturosa | 92 | 87.0% (80/92) | 13.0% (12/92) | 97.8% (90/92) | 78.3% (72/92) | 65.2% (60/92) | 52.2% (48/92) |

| H. Longicornis | 120 | / | / | 80.0% (96/120) | 66.7% (80/120) | 76.7% (92/120) | 0% |

| Dermacentor niveus | 102 | / | / | 88.2% (90/102) | 35.3% (36/102) | 88.2% (90/102) | 58.8% (60/102) |

Amplification of the 18S/16S rDNA or msp4 genes and their accession numbers

The nearly full-length 18S rDNA sequences of T. luwenshuni were 1745 bp with the primers A/B, and the accession numbers are KM186951–KM186957. The nearly full-length 16S rDNA sequences were 1457 bp in A. bovis (KM186936–KM186944), 1458 bp in A. phagocytophilum (KM186947–KM186950), and 1456 bp in A. ovis (KM246795 and KM246796) with primers EC12/EC12A, which are specific for Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp. An unknown Anaplasma sp. was isolated and its accession number was KM227012. The msp4 gene PCR products were 551 bp for A. bovis (KM226988, KM226999, KM227002, and KM227003), 641 bp for A. phagocytophylum (KM227007–KM227009), and 347 bp for A. ovis (KM227005 and KM227006) when species-specific primers were used.

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses

The phylogenetic tree based on the Theileria and Babesia 18S rDNA sequences showed that only one pathogen was detected, which was placed in the T. luwenshuni cluster (Figure 2). The phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rDNA sequences of Anaplasma and Ehrlichia revealed four pathogens existed and they were A. bovis, A. phagocytophilum, A. ovis, and Anaplasma sp., respectively, in the blood samples from P. gutturosa roaming northern China (Figure 3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the prevalence of theileriosis and anaplasmosis in P. gutturosa in China. Molecular screening of P. gutturosa in northern China showed that the most prevalent Theileria and Anaplasma species were, in descending order: T. luwenshuni > A. bovis > A. phagocytophilum > A. ovis. No other Theileria sp. or Anaplasma sp. was detected in P. gutturosa. The prevalence of T. luwenshuni and A. bovis in P. gutturosa was higher than their prevalence in H. longicornis or D. niveus. However, the prevalence of A. phagocytophilum was, in descending order: D. niveus > H. longicornis > P. gutturosa. We speculate that persistent pathogen reservoirs with high infection rates are well established in P. gutturosa in northern China.

Anaplasma bovis infections of cattle have been reported predominantly in African countries, and there have been few reports of bovine A. bovis infections in China. Recently, A. ovis and A. bovis were reported in goats in central and southern China, and A. marginale was detected in cattle in southern China [9]. A. bovis and A. ovis have also been reported in red deer, sika deer, and D. everestianus in north-western China [12]. In Japan, A. bovis and A. centrale have been detected in wild deer and H. longicornis ticks on Honshu Island, Japan [10]; A. bovis and A. phagocytophilum were initially detected in cattle on Yonaguni Island, Okinawa, Japan [19]. Therefore, H. megaspinosa is considered a dominant vector tick species for both these species in cattle in Japan [20]. In this study, four Anaplasma spp. (A. bovis, A. ovis, A. phagocytophilum, and an Anaplasma sp.) were detected in P. gutturosa. Rickettsia raoultii was also detected for the first time in P. gutturosa in China.

In this study, all 242 ticks were collected from gazelle or from their environment in the investigated area. They consisted of H. longicornis and D. vineus. Theileria luwenshuni and Anaplasma spp. (including A. bovis, A. phagocytophilum, A. ovis, and Anaplasma sp.) were detected and identified by PCR. Therefore, we speculate that these ticks play an important role as natural vectors of Anaplasma spp. in northern China. Theileria luwenshuni were first reported in sheep and goats, and widely distributed in north-western China [21]; recently, it was also reported in sheep and goats in central and southern China [22-24]. T. luwenshuni can be transmitted by H. qinghaiensis and H. longicornis in north-western China [25], but only H. longicornis and D. niveus were found in this study. Therefore, H. longicornis must play an important role as a natural vector of T. luwenshuni in P. gutturosa in northern China. However, whether T. luwenshuni can be transmitted by D. niveus remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Our results provide important data that extend our understanding of the epidemiology of theileriosis and anaplasmosis, and should facilitate the implementation of measures to control the transmission of Theileria and Anaplasma among P. gutturosa and other relative ruminants in China. Clarification of the role of P. gutturosa as a reservoir host for some Theileria and Anaplasma species is critical in determining whether P. gutturosa contributes to the spread of ruminant theileriosis and anaplasmosis in China.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported financially by the Natural Sciences of Foundation China (no. 31272556, no. 31372432, no. 31101621, no. 31201899), ASTIP, FRIP (2014ZL010), CAAS, Creative Research Groups of Gansu Province (no. 1210RJIA006), NBCIS (CARS-38), “948” (2014-S05), the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in Public Research (no. 201303035, no. 201303037), MOA; 973 Program (2010CB530206), Basic Research Program (CRP no. 16198/R0), Supporting Program (2013BAD12B03, 2013BAD12B05), Specific Fund for Sino-Europe Cooperation, MOST, China; and the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology Project. The research was also supported by CRP (no. 16198/R0 IAEA) and PIROVAC (KBBE-3-245145) of the European Commission. Thanks for the revision by Edanz Group Ltd (China).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

QR and GG collected the samples; YL, ZC, ZL, and JL performed the molecular genetic studies; JY, QL, YL, and SC performed the sequence alignments; YL, JL, and HY drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Youquan Li, Email: youquan-li@163.com.

Ze Chen, Email: chenze@caas.cn.

Zhijie Liu, Email: liuzhijie@caas.cn.

Junlong Liu, Email: liujunlong@caas.cn.

Jifei Yang, Email: yangjifei@caas.cn.

Qian Li, Email: liqian0225@126.com.

Yaqiong Li, Email: liyaqiong624@163.com.

Qiaoyun Ren, Email: renqiaoyun@caas.cn.

Qingli Niu, Email: niuqingli@caas.cn.

Guiquan Guan, Email: guanguiquan@caas.cn.

Jianxun Luo, Email: luojianxun@caas.cn.

Hong Yin, Email: yinhong@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Dumler JS, Choi KS, Garcia-Garcia JC, Barat NS, Scorpio DG, Garyu JW, Grab DJ, Bakken JS. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1828–1834. doi: 10.3201/eid1112.050898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen SM, Dumler JS, Bakken JS, Walker DH. Identification of a granulocy to tropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aktas M, Altay K, Dumanli N. Molecular detection and identification ofAnaplasmaandEhrlichiaspecies in cattle from Turkey. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aktas M, Altay K, Ozubek S, Dumanli N. A survey of ixodid ticks feeding on cattle and prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in the Black Sea region of Turkey. Vet Parasitol. 2012;187:567–571. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aktas M. A survey of ixodid tick species and molecular identification of tick-borne pathogens. Vet Parasitol. 2014;200:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silaghi C, Woll D, Hamel D, Pfister K, Mahling M, Pfeffer M. Babesia spp. and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in questing ticks, ticks parasitizing rodents and the parasitized rodents–analyzing the host-pathogen-vector interface in a metropolitan area. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:191. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silveira JA, Rabelo EM, Ribeiro MF. Molecular detection of tick-borne pathogens of the family Anaplasmataceae in Brazilian brown brocket deer (Mazama gouazoubira, Fischer, 1814) and marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus, Illiger, 1815) Transbound Emerg Dis. 2012;59:353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarih M, M’Ghirbi Y, Bouattour A, Gern L, Baranton G, Postic D. Detection and identification of Ehrlichia spp. in ticks collected in Tunisia and Morocco. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1127–1132. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1127-1132.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z, Ma M, Wang Z, Wang J, Peng Y, Li Y, Guan G, Luo J, Yin H. Molecular survey and genetic identification of Anaplasma species in goats from central and southern China. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:464–470. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06848-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawahara M, Rikihisa Y, Lin Q, Isogai E, Tahara K, Itagaki A, Hiramitsu Y, Tajima T. Novel genetic variants of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Anaplasma bovis, Anaplasma centrale, and a novel Ehrlichia sp. in wild deer and ticks on two major islands in Japan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1102–1109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1102-1109.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torina A, Agnone A, Blanda V, Alongi A, D'Agostino R, Caracappa S, Marino AM, Di Marco V, de la Fuente J. Development and validation of two PCR tests for the detection of and differentiation between Anaplasma ovis and Anaplasma marginale. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Chen Z, Liu Z, Liu J, Yang J, Li Q, Li Y, Cen S, Guan G, Ren Q, Luo J, Yin H. Molecular identification of Theileria parasites of north-western Chinese Cervidae. Parasit Vectors. 2014;14(7):225. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Liu Q, Liu JQ, Xu BL, Lv S, Xia S, Zhou XN. Tick-borne pathogens and associated co-infections in ticks collected from domestic animals in central China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:237. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medlin L, Elwood HJ, Stickel S, Sogin ML. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allsopp BA, Baylis HA, Allsopp MT, Cavalier-Smith T, Bishop RP, Carrington DM, Sohanpal B, Spooner P. Discrimination between six species of Theileria using oligonucleotide probes which detect small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Parasitol. 1993;107:157–165. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000067263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin H, Liu Z, Guan G, Liu A, Ma M, Ren Q, Luo J. Detection and differentiation of Theileria luwenshuni and T. uilenbergi infection in small ruminants by PCR. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2008;55:233–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2008.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramos CM, Cooper SM, Holman PJ. Molecular and serologic evidence forBabesia bovis-like parasites in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in south Texas. Vet Parasitol. 2010;172:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng KF, and Jiang ZJ: Economic Insect Fauna of China. Fasc 39, Acari: Ixodidae. Science Press 1991, 158–181.

- 19.Ooshiro M, Zakimi S, Matsukawa Y, Katagiri Y, Inokuma H. Detection of Anaplasma bovis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum from cattle on Yonaguni Island, Okinawa, Japan. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimoto K, Matsuyama Y, Matsuda H, Sakamoto L, Matsumoto K, Yokoyama N, Inokuma H. Detection of Anaplasma bovis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum DNA from Haemaphysalis megaspinosa in Hokkaido, Japan. Vet Parasitol. 2010;168:170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin H, Schnittger L, Luo JX, Ulrike S, Ahmed J. Ovine theileriosis in China: a new look at an old story. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:S191–S195. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, Chen Z, Yang J, He H, Guan G, Liu A, Ren Q, Niu Q, Liu J, Luo J, Yin H. An epidemiological survey of Theileria infections in small ruminants in central China. Vet Parasitol. 2014;200:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Mao Y, Kelly P, Yang Z, Luan L, Zhang J, Li J, El-Mahallawy HS, Wang C. A: pan-Theileria FRET-qPCR survey for Theileria spp. in ruminants from nine provinces of China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):413. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu XB, Na RH, Wei SS, Zhu JS, Peng HJ. Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:119. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Luo J, Liu Z, Guan G, Gao J, Ma M, Dang Z, Liu A, Ren Q, Lu B, Liu J, Zhao H, Li J, Liu G, Bai Q, Yin H. Experimental transmission of Theileria sp. (China 1) infective for small ruminants by Haemaphysalis longicornis and Haemaphysalis qinghaiensis. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:533–538. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]