Abstract

Background

Limited health literacy is a known barrier to medication adherence among people living with HIV. Adherence improvement interventions are urgently needed for this vulnerable population.

Purpose

This study tested the efficacy of a pictograph-guided adherence skills building counseling intervention for limited literacy adults living with HIV.

Methods

Men and women living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART, N=446) who scored below 90% correct on a test of functional health literacy were partitioned into marginal and lower literacy groups and randomly allocated to one of three adherence-counseling conditions: (a) pictograph-guided adherence counseling, (b) standard adherence counseling, or (c) general health improvement counseling. Participants were followed for 9-months post-intervention with unannounced pill count adherence and blood plasma viral load as primary endpoints.

Results

Preliminary analyses demonstrated the integrity of the trial and more than 90% of participants were retained. Generalized estimating equations showed significant interactions between counseling conditions and levels of participant health literacy across outcomes. Participants with marginal health literacy in the pictograph-guided and standard-counseling conditions demonstrated greater adherence and undetectable HIV viral loads compared to general health counseling. In contrast and contrary to hypotheses, participants with lower health literacy skills in the general health improvement counseling demonstrated greater adherence compared to the two adherence counseling conditions.

Conclusions

Patients with marginal literacy skills benefit from adherence counseling regardless of pictographic tailoring and patients with lower literacy skills may require more intensive or provider directed interventions.

Keywords: HIV Treatment, Adherence Intervention, Health Literacy

Introduction

HIV epidemics remain concentrated in the poorest and most disadvantaged communities. Significant advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART) result in better management of HIV infection but these benefits are not equally shared by all people living with HIV. (1, 2) Among factors known to impede medication adherence are poor health literacy skills, particularly difficulty reading and interpreting medical information. (3) While the most prevalent reasons for missing medications are based on memory lapses, poor-literacy skills preclude the use of written reminders and other verbal systems commonly used to enhance adherence.(4) Patients with lower-literacy skills may not understand the repercussions of non-adherence, which can lead to intentionally missing medications to relieve side-effects, taking drug holidays, or cleansing their body. (5–9) Indeed, impediments to adherence may account for the poorer health outcomes consistently observed in lower-literacy medical populations.(10, 11)

The association between health literacy and ART adherence appears quite robust (7, 12–18) Unfortunately, few adherence interventions have addressed literacy skills and we are not aware of any ART adherence interventions tailored for limited literacy populations tested in controlled trials.(19–21) The purpose of the current research was to test a pictograph-guided patient education and skills-building intervention to improve ART adherence for people with marginal and lower literacy skills. We designed a counseling intervention for use in clinical care with minimal demands on reading skills and pictographically presented treatment-relevant information. We tested the pictograph-guided intervention in comparison to both standard adherence counseling and time-matched general health improvement counseling. We hypothesized that for patients with lower-literacy skills, pictograph-guided counseling would result in greater use of adherence skills, HIV suppression and ART adherence compared to both standard adherence and general health improvement counseling. We also hypothesized that the benefits of pictograph-guided counseling would not be observed in patients with marginal literacy skills.

Methods

Participants and setting

Participants were men and women recruited from AIDS services and community outreach in Atlanta, GA a city with among the fastest growing HIV epidemics in the United States. (22) The study commenced November 2008, enrollment ended in April 2011, and follow-ups were completed April 2012.

Ethical review

This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT01061762. All study protocols were approved by the University of Connecticut IRB and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. There were two adverse events that were unrelated to study activities: participant injuries sustained while coming to the study.

Overview of intervention conditions

The three experimental conditions in this trial were implemented using matched operational protocols and procedures. All interventions were conducted at the same community-based research site. The three counseling conditions were grounded in Social-Cognitive Theory of behavior change (23, 24) and designed for use in HIV treatment settings. The interventions were formatted to deliver two 60 min. one-on-one counseling sessions over two weeks and a third 30 min. booster session two weeks later. The same interventionists delivered all three manual-based and patient-education flipchart driven counseling conditions. All counselors received extensive training in each condition and attended weekly supervision.

Pictograph-guided adherence counseling

Following the initial formative study period, we designed a treatment adherence intervention tailored for people with lower-health literacy skills. This intervention was extensively pilot tested in a Phase-I trial described elsewhere. (25) The content of the intervention relied on pictographic information particularly relevant to an individual’s medication regimen. The intervention concentrated on delivering the most relevant information for treatment adherence including the importance of following prescribed instructions for each drug. We also included motivational enhancement techniques including providing direct feedback on participant health status and training in self-monitoring skills for changes in adherence and viral load. We tailored medication instructions to lower levels of reading literacy, including the use of memory cues for fitting medications into daily routines using strategies described in earlier research. (26)

A primary aim of the intervention was to integrate intensive interactions with pictograph-guided instructions. (27) The intervention materials were developed with minimal words, modeled after similar interventions that have been effective in other areas of health promotion (e.g., (27, 28) The intervention sessions were guided by a tabletop flipchart that moved the counselor and participant together through each intervention component. In addition, a pocket-size pamphlet was developed to represent the participant’s medication regimen, as well as dosing times and administration instructions. The counselor and participant therefore created an individualized adherence plan within the context of two counseling sessions. Participants were given an array of adherence tools of their choosing, including pillboxes, watch alarms, reminder notes etc. The adherence tools were discussed in the context of current medications and current efforts to remain adherent. Planning and problem solving skills were central to the goals of the counseling sessions. The third and final session was a booster that applied problem solving strategies to challenging situations that occurred since the previous session (two weeks earlier). Situations in which medications may have been missed or not taken on schedule were recreated and role-played for problem solving with the aim of improving future adherence.

Standard adherence counseling

As a comparison condition, we included interactive counseling that delivered educational information about HIV treatments, viral suppression, side effects, and the role of adherence in preventing viral resistance. The standard counseling was guided by a participant education flipchart that included brief verbal descriptions of concepts that the participant and counselor could read together as they talked. Text was used throughout the materials that included illustrations of HIV infection processes and comic strips depicting the HIV disease process as an alien invasion. Problem solving skills were applied to situations that create challenges for medication adherence. Participants were given a pillbox and discussed how they could use it and other tools to improve adherence. The third session was a brief booster guided by challenges to adherence that the participant experienced during the previous two weeks.

General health improvement counseling

The control arm was contact-matched non-contaminating health improvement counseling for individuals living with HIV. This condition concentrated on improving general health and well-being in relation to living with HIV. The first session focused on understanding nutrition in terms of food groups including how to read a food label and relate nutritional information to diet and food choices. The second session focused on stress reduction, relaxation and exercise to improve health and well-being. The session ended with participants setting personal health goals and selecting health improvement tools such as pillboxes, pedometers, hand-squeeze balls, and nutrition guides. The third session was a brief booster that discussed and problem solved barriers to achieving personal health improvement goals.

Measures

Reading literacy

Reading-literacy was assessed at screening with the reading comprehension scale of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults [TOFHLA, (29, 30)] The scale is timed and includes 50 multiple-choice items, in which selecting the correct word among four options completes sentences from standard medical instructions. Scores ranged from 0 to 50 with the percent correct computed for the total score.

Numeracy literacy

We also administered the TOFHLA Numeracy Scale that assesses numerical reasoning for medical instructions.(30) For the purposes of the current study, the Numeracy Scale was used to internally validate literacy groups based on the TOFHLA reading comprehension scale.

Vision

Participants were asked a series of questions regarding their vision and use of corrective lenses. Participants who complained of blurred vision during reading were offered non-prescription reading glasses.

Computerized interviews

For self-report instruments participants completed 30 min. audio-computerized self-interviewing (ACASI) at baseline and 3-month and 9-month post-intervention follow-ups. (13, 14) Participants reported demographic information, the date they tested HIV positive, and their income/disability status. We also assessed 14 HIV-related symptoms of 2-weeks duration. (15) Adherence strategies and skills were also assessed to serve as secondary outcomes. (31) Specifically, participants indicated whether they had used 13 common memory-based strategies for improving medication adherence. (32, 33)

Baseline viral load and CD4 counts

We used a participant assisted method for collecting baseline chart abstracted viral load and CD4 cell counts from participants’ medical records. Participants were given a form that requested their doctor’s office to provide results and dates of their most recent viral load and CD4 cell counts. The form included a place for the provider’s office stamp or signature to assure authenticity.

Primary outcomes: HIV RNA viral load and ART adherence

HIV RNA viral load

Participants provided blood specimens to test for HIV (RNA) viral load at the final follow-up assessment. Blood samples were provided at the project offices using standard phlebotomy and were couriered to the lab for processing. Whole blood specimens in EDTA tube (Becton Dickinson) were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min within 4 hrs of collection. The plasma was recovered and aliquoted into 1 ml samples and stored at −70°C. Prior to August 2010 HIV-1 viral load was determined using the ultra-sensitive version of the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test (Roche Diagnsotics, Indianapolis, IN), with a lower limit of quantification of 50 copies/ml. From August 2010 forward HIV-1 viral load was measured using the RealTime HIV-1 assay (Abbott Molecular) with a lower limit of quantification of 40 copies/ml. For consistency across assays and baseline chart values, we defined undetectable viral load as less than 50 copies/ml.

ART adherence

HIV treatment adherence was monitored with monthly-unannounced telephone-based pill counts. Unannounced pill counts are a reliable and valid measure of ART adherence when conducted in participants’ homes and on the telephone (34, 35), including demonstrated reliability and validity among people with poor literacy skills.(36–38) Unannounced pill counts are an objective measure of adherence, not subject to reporting biases. In order for participants to fabricate their pill counts they would have to mentally calculate missed doses into missed pills since the last unannounced call which occurred a month earlier while also knowing how many pills they should have taken and how many pills they had counted on the previous call, an exceedingly difficult task. Participants were provided with a free cell phone that restricted service for project contacts and emergency use. Following the initial office-based training in the pill counting procedure, participants were called every 21 to 35 days at unscheduled times by a phone assessor. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was also collected to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed, taking into account the number of pills dispensed. The first three pill counts occurred prior to the baseline assessment allowing us to calculate pre-intervention adherence.

Sample size

A moderate effect size (d=.35) was used to calculate statistical power for both primary endpoints.(39, 40) We assumed 80% retention and estimated a sample of 140 for each primary outcome to achieve 90% chance of detecting differences between groups.

Recruitment and enrollment

We notified AIDS service providers and infectious disease clinics throughout Atlanta about the study opportunity. Interested persons phoned the research site to schedule an intake appointment. People living with HIV and taking ART were enrolled in a run-in study to screen for literacy skills. Participants with TOFHLA scores below 90% correct were recruited for participation in the trial. We selected this liberal cut-off to screen out individuals with higher reading ability while minimizing the exclusion of lower-literacy participants. The additional study entry criteria were (a) age 18 or older and (b) proof of positive HIV status and current use of ART with a photo ID matching a current ART prescription bottle.

Literacy groups

Within the sample, we defined marginal literacy as scoring between 85% and 90% correct on the TOFHLA and lower-literacy as scoring below 85% correct (29) Marginal / lower literacy was treated as a blocking variable in all outcome analyses.

Randomization and blinding

Following the baseline assessment and the first three unannounced phone assessments, the Project Manager randomly assigned participants to conditions. Allocation was accomplished using an automated randomization generator accessed at www.randomizer.org. Randomization was not breached throughout the trial. Recruitment, screening, office-based assessment, and telephone assessment staff remained blinded to condition throughout the study and interventionists never conducted assessments.

Statistical analyses

We first examined differences between conditions on demographic and health characteristics using analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous measures and contingency table chi-square tests for categorical variables. We also used procedures suggested by Jurs and Glass (41) to test baseline equivalence between conditions and effects of attrition on dependent measures.

Primary and secondary outcome analyses used an intent-to-treat approach where all available follow-up data from participants was included in the analyses regardless of their exposure to the intervention sessions. Primary outcome analyses for adherence and viral load used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with unstructured working correlation matrixes. All outcome analyses controlled for baseline values. Counseling condition, literacy level, time of assessment, and all interactions were entered as model effects. Planned contrasts with least significant difference adjustment were used to test for simple effects. Adherence outcomes represent over-dispersed count data and therefore used Poisson distribution. To simplify interpretation of results we report the 95% ART adherence outcomes at each assessment point. For viral load outcomes, we performed GEE models for both the log-values (continuous scale) and dichotomously coded detectable/undetectable (binomial). Finally, secondary outcomes for adherence strategies at 3- and 9-month post-intervention follow-ups were analyzed using logistic regression models for use or non-use of each strategy among participants who did not report using the strategy at baseline. We also created a composite score for total aggregated adherence strategies reported at the 3- and 9-month follow-ups. Differences between intervention and literacy groups for aggregated strategies were tested using ANOVA, controlling for number of strategies used at baseline. All main outcome analyses and planned comparisons defined statistical significance as p < .05.

Results

Preliminary analyses showed that there were no differences between intervention conditions at baseline. (see Table 1). Participants’ ART regimens included Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (RTIs, N =404, 90%), Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs, N = 51, 11%), Protease Inhibitors (PIs, N = 296, 66%), Integrase inhibitors (N = 38, 9%), and multi-class single pills (N = 83, 18%). ART classes were proportional across conditions as were the number of pills and doses taken per day and there were no differences on baseline measures of adherence, viral load, or behavioral skills. Marginal literacy participants were younger (M = 46.0, SD = 8.0) and had more years of education (M = 12.5, SD = 1.6) than lower-literacy participants [M = 48.0, SD = 7.9, t(444) = 2.6, p < .01; M = 11.6, SD = 1.8, t(444) = 5.09, p < 01, respectively]. The literacy groups did not differ on any other demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and health characteristics of clinical trial participants.

| Characteristic | Pictograph Guided (N = 148) | Standard Adherence (N = 157) | General Health Improvement (N = 141) | F | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Age | 46.7 | 7.3 | 47.0 | 8.4 | 47.8 | 8.3 | 0.6 | ns |

| Years of education | 12.0 | 1.7 | 12.0 | 1.8 | 11.9 | 1.8 | 0.5 | ns |

| Years since testing HIV+ | 14.0 | 7.4 | 13.6 | 7.3 | 13.0 | 6.6 | 0.7 | ns |

| HIV symptoms | 5.1 | 3.1 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 0.1 | ns |

| CD4 cell count | 411 | 313.2 | 404 | 250.2 | 437 | 288.9 | 0.5 | ns |

| Number of pills/day | 3.0 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 1.3 | ns |

| % Correct reading literacy | 72.2 | 22.9 | 73.9 | 20.8 | 72.4 | 21.4 | 0.3 | ns |

| % Correct numeracy literacy | 64.1 | 25.4 | 67.7 | 27.3 | 64.3 | 26.2 | 0.9 | ns |

|

|

||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | X2 | ||

|

|

||||||||

| Men | 104 | 70 | 115 | 73 | 91 | 65 | ||

| Women | 44 | 30 | 42 | 27 | 50 | 36 | 2.7 | ns |

| African-American | 137 | 93 | 152 | 97 | 132 | 94 | 2.8 | ns |

| Currently unemployed | 42 | 28 | 50 | 32 | 38 | 27 | 6.4 | ns |

| Disabled status | 96 | 65 | 95 | 60 | 100 | 71 | ||

| Income < $10,000 year | 101 | 69 | 111 | 71 | 105 | 75 | 1.1 | ns |

| TOFLA < 85% correct | 86 | 58 | 84 | 53 | 57 | 40 | 1.2 | ns |

| CD4 count < 200 cell/cc | 39 | 26 | 39 | 25 | 30 | 21 | 1.1 | ns |

| Medication doses/day | ||||||||

| 1 | 74 | 50 | 89 | 57 | 76 | 54 | ||

| 2 | 74 | 50 | 67 | 43 | 64 | 46 | 0.9 | ns |

| Number HIV Hospitalizations | ||||||||

| 0 | 66 | 45 | 69 | 44 | 61 | 43 | 1.7 | ns |

| 1 | 21 | 14 | 28 | 18 | 29 | 21 | ||

| 2 | 13 | 9 | 18 | 12 | 26 | 18 | ||

| 3+ | 48 | 37 | 42 | 26 | 25 | 18 | ||

| Knows CD4 count | 115 | 78 | 128 | 82 | 118 | 84 | 1.7 | ns |

| Knows viral load | 108 | 73 | 116 | 74 | 105 | 75 | 0.1 | ns |

| Alcohol in the past 3 months | 69 | 47 | 77 | 50 | 59 | 42 | 5.5 | ns |

| Brings someone to doctor to help with reading | 28 | 17 | 21 | 13 | 18 | 12 | 2.4 | ns |

|

| ||||||||

| Assisted with completing medical forms | 54 | 34 | 62 | 38 | 51 | 33 | 0.7 | ns |

| Wears reading glasses | 98 | 62 | 107 | 66 | 101 | 67 | 0.8 | ns |

| Experiences difficulty reading | 74 | 50 | 77 | 47 | 81 | 53 | 1.7 | ns |

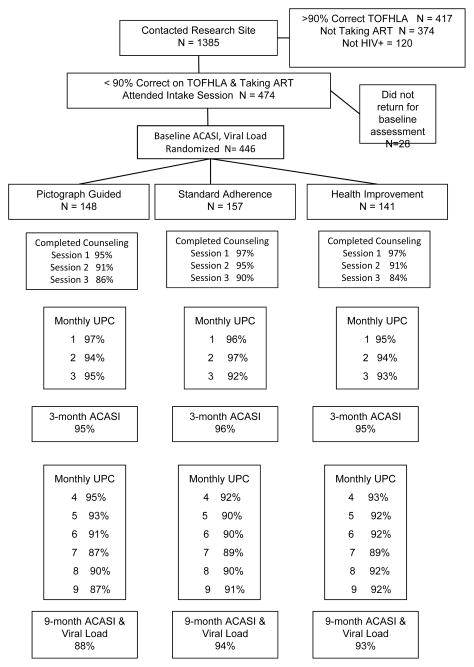

As shown in Figure 1, counseling session attendance was proportional across conditions: 96% of participants attended at least one counseling session and 86% attended all three sessions. The trial retained over 92% of participants randomized to conditions for ACASIs and 90% for monthly telephone assessments; 78% (n=348) completed all 9 monthly post-intervention assessment calls (Mean = 8.3, SD=1.6). Two participants were known to have died during the trial, three withdrew and three moved out of state. Attrition was proportional for the two conditions at 3- and 9-month follow-ups. Planned attrition analyses did not find differences between participants retained and lost by condition.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participants in the randomized clinical trial of ART adherence for people with lower health literacy. ART = Antiretroviral therapy; ACASI = Audio computer assisted self-interview; UPC = Unannounced pill count; TOFHLA = Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults;

HIV RNA viral load primary outcomes

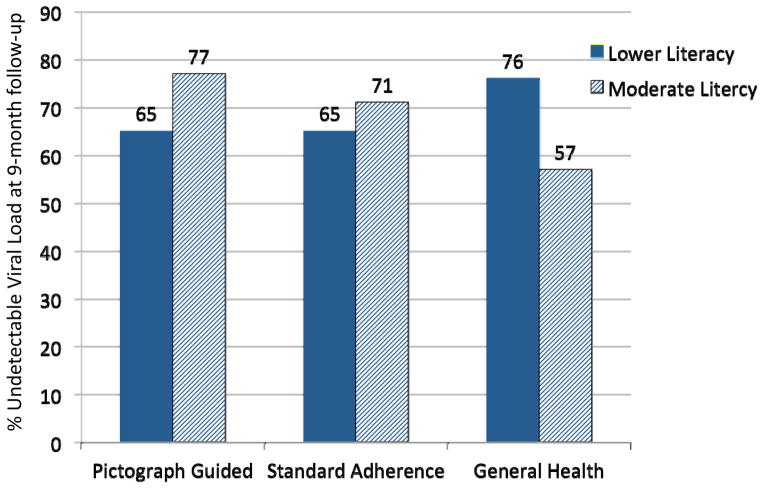

The mean log-values for HIV RNA viral load at baseline and follow-ups for the counseling conditions and literacy groups are shown in Table 2. Analyses indicated that there were no main effects at the follow-up viral load testing for counseling conditions, Wald X2(2) = 0.45, p > .1, or literacy groups, Wald X2(1) = 1.88, p > .1. However, there was a significant counseling condition by literacy group interaction, Wald X2(2) = 6.80, p < .03. The condition by literacy group interaction effect was also significant for participants achieving undetectable viral loads nine months after counseling, Wald X2(2) = 2.05, p < .01 (see Figure 2). Among the marginal literacy participants who had a detectable viral load at baseline, 40% of the pictograph-guided and 45% of the standard adherence counseling conditions achieved an undetectable viral load at the follow-up, compared to 33% of the general health improvement condition. In contrast, for the lower-literacy participants only 28% who received pictograph-guided counseling who had detectable viral loads at baseline achieved an undetectable viral load at the follow-up compared to 35% of participants in the standard adherence counseling and 40% of those in the general health improvement condition.

Table 2.

Log-viral load and proportion of participants achieving 95% adherence at baseline and follow-up unannounced pill counts for the three intervention conditions.

| Marginal Literacy Participants | Pictograph Guided | Standard Adherence | General Health Improvement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Baseline viral load | 2.10 | 0.72 | 2.18 | 0.98 | 1.98 | 0.64 |

| 9-month viral load1 | 2.07a | 0.95 | 2.08a | 0.90 | 2.25b | 0.96 |

|

|

||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

|

|

||||||

| Baseline adherence | 19 | 30 | 25 | 34 | 18 | 34 |

| 1-month adherence | 23 | 42 | 30 | 42 | 20 | 41 |

| 2-month adherence | 29 | 55a | 32 | 45b | 24 | 49b |

| 3-month adherence | 24 | 44 | 29 | 42 | 20 | 42 |

| 4-month adherence | 28 | 53a | 27 | 40b | 18 | 38b |

| 5-month adherence | 22 | 42 | 26 | 41 | 19 | 41 |

| 6-month adherence | 24 | 47 | 26 | 42 | 21 | 45 |

| 7-month adherence | 19 | 31 | 19 | 26 | 14 | 25 |

| 8-month adherence | 21 | 35 | 23 | 31 | 19 | 35 |

| 9-month adherence | 20 | 45 | 22 | 37 | 21 | 45 |

|

|

||||||

| Lower Literacy Participants | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

|

|

||||||

| Baseline viral load | 2.08 | 0.81 | 2.23 | 1.00 | 2.10 | 0.81 |

| 9-month viral load1 | 2.29a | 1.19 | 2.25a | 1.14 | 2.00b | 0.88 |

|

|

||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

|

|

||||||

| Baseline adherence | 28 | 33 | 28 | 34 | 33 | 39 |

| 1-month adherence | 31 | 43a | 36 | 51b | 47 | 61c |

| 2-month adherence | 26 | 34a | 38 | 55b | 40 | 54b |

| 3-month adherence | 30 | 41 | 33 | 48 | 37 | 51 |

| 4-month adherence | 32 | 44a | 30 | 43a | 40 | 56b |

| 5-month adherence | 26 | 36 | 34 | 51 | 36 | 52 |

| 6-month adherence | 29 | 42 | 32 | 50 | 31 | 45 |

| 7-month adherence | 17 | 21 | 28 | 33 | 27 | 32 |

| 8-month adherence | 30 | 36 | 36 | 43 | 33 | 40 |

| 9-month adherence | 28 | 45 | 30 | 44 | 39 | 57 |

Note:

Different letter superscripts indicate significant group differences;

Main effect on viral load for intervention condition, Wald X2 = 0.45, ns; Interaction effect on viral load for intervention x literacy group controlling for baseline, Wald X2 = 6.80, p < .05.

Figure 2.

Percent participants with undetectable HIV RNA viral loads (< 50 copies/ml) at 9-months follow-up for people with marginal and lower health literacy randomized to three ART adherence counseling interventions.

Treatment adherence primary outcomes

Table 2 shows the percentages of participants in each condition within literacy groups who achieved greater than 95% adherence at each time point. GEE models for monthly-unannounced pill count adherence indicated that there were no main effects for condition or literacy group, although there was a main effect for time, Wald X2 (8) = 19.72, p < .01. Paralleling the viral load outcomes, there was a significant intervention condition by literacy group interaction effect, Wald X2(2) = 5.93, p < .05. Planned comparisons showed that significant differences between conditions were observed at the 1-month follow-up, Wald X2(2) = 4.66, p < .05, 2-month follow-up, Wald X2(2) = 4.73, p < .05, and 4-month follow-up, Wald X2(2) = 4.75, p < .05. Results showed that among marginal health literacy participants, the pictograph-guided and standard adherence counseling conditions demonstrated greater adherence compared to the general health improvement counseling. The difference between the pictographic and standard conditions was not significant. In contrast, lower-literacy participants in the general health improvement counseling condition demonstrated greater adherence than those in the pictograph-guided and standard adherence counseling.

Behavioral adherence strategy secondary outcomes

Results of logistic regression models testing the use and non-use of 13 behavioral adherence strategies controlling for baseline use and including literacy group, indicated significant intervention condition differences at the 3-month follow-up. (see Table 3) Analysis of the behavioral strategy composite measure indicated a main effect for condition, F(2, 426) = 3.40, p < .05; the two adherence counseling interventions used significantly more strategies than the health improvement counseling condition. There was also a significant intervention condition by literacy group interaction, F(2, 426) = 3.1, p < .05; lower literacy participants in the pictograph-guided and standard counseling conditions used more strategies than the health improvement condition. However, among the marginal literacy participants, the pictograph-guided counseling condition reported greater use of adherence strategies compared to the standard and health improvement counseling conditions.

Table 3.

Behavioral strategies for medication adherence among participants in the three intervention conditions.

| 3-Month Follow-up | Pictograph Guided (N = 158) | Standard Adherence (N = 163) | General Health Improvement (N = 151) | OR | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Pill Box | 102 | 73 | 82 | 54 | 65 | 49 | 0.56 | .01 |

| Kept medications in an easily seen place | 103 | 72 | 99 | 65 | 79 | 59 | 0.62 | .01 |

| Used a case or bag | 98 | 69 | 91 | 60 | 80 | 60 | 0.85 | ns |

| Clock/timer | 53 | 37 | 36 | 24 | 33 | 25 | 0.56 | .01 |

| Watch alarm | 45 | 31 | 30 | 20 | 28 | 21 | 0.62 | .05 |

| Friend or family | 46 | 32 | 44 | 29 | 42 | 31 | 0.95 | ns |

| Meal time | 92 | 65 | 94 | 62 | 76 | 57 | 0.79 | ns |

| Bed time | 83 | 58 | 101 | 67 | 72 | 54 | 0.89 | ns |

| Routine activity | 75 | 52 | 77 | 51 | 55 | 41 | 0.75 | ns |

| Moved medications | 44 | 31 | 49 | 32 | 34 | 25 | 0.87 | ns |

| Written notes/post its | 22 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 0.99 | ns |

| Calendar | 51 | 36 | 59 | 39 | 42 | 31 | 0.90 | ns |

| Reminders | 35 | 25 | 35 | 23 | 20 | 15 | 0.58 | .01 |

| Total strategies (M,SD) | ||||||||

| Total Sample | 5.9a | 3.1 | 5.3a | 3.0 | 4.8b | 3.2 | 3.4a | .05 |

| Lower Literacy | 6.1a | 3.0 | 5.6a | 3.4 | 4.7b | 3.5 | 3.1b | .05 |

| Marginal Literacy | 5.7a | 3.2 | 5.0b | 3.6 | 4.9b | 2.9 | ||

| 9-Month Follow-up | ||||||||

| Pill Box | 80 | 61 | 73 | 49 | 63 | 48 | 0.64 | .05 |

| Kept medications in an easily seen place | 93 | 71 | 99 | 67 | 76 | 58 | 0.74 | ns |

| Used a case or bag | 88 | 67 | 96 | 65 | 74 | 56 | 0.80 | ns |

| Clock/timer | 49 | 37 | 38 | 25 | 22 | 16 | 0.37 | .01 |

| Watch alarm | 38 | 29 | 42 | 28 | 18 | 14 | 0.61 | .01 |

| Friend or family | 37 | 28 | 43 | 29 | 36 | 27 | 0.90 | ns |

| Meal time | 79 | 60 | 89 | 60 | 70 | 53 | 0.84 | ns |

| Bed time | 73 | 55 | 95 | 65 | 74 | 56 | 0.83 | ns |

| Routine activity | 63 | 48 | 75 | 51 | 49 | 37 | 0.69 | .05 |

| Moved medications | 41 | 31 | 4 | 30 | 36 | 27 | 0.97 | ns |

| Written notes/post its | 17 | 13 | 20 | 13 | 18 | 13 | 0.85 | ns |

| Calendar | 47 | 25 | 53 | 35 | 39 | 30 | 0.88 | ns |

| Reminders | 27 | 21 | 31 | 21 | 21 | 16 | 0.75 | ns |

| Total strategies (M,SD) | ||||||||

| Total Sample | 5.5a | 3.0 | 5.3a | 3.3 | 4.5b | 3.1 | 2.70a | ns |

| Lower Literacy | 5.6a | 3.0 | 5.5a | 3.5 | 4.3b | 3.2 | ||

| Marginal Literacy | 5.5a | 3.0 | 5.1a | 2.9 | 4.8b | 2.9 | 3.4b | .05 |

Note:

F-test for main effect of intervention condition;

F-test for interaction effect of intervention x literacy group.

Similar results were observed at the 9-month follow-up. The pictograph-guided counseling condition reported the greatest use of strategies. The main effect for intervention condition was not significant, F(2, 409) = 2.70, p < .06. However, the intervention condition by literacy group interaction was significant, F(2, 409) = 3.40, p < .05; lower literacy participants in the pictograph-guided and standard adherence counseling interventions again reported more use of adherence strategies than the general health counseling condition, whereas among marginal literacy participants, the pictograph-guided counseling condition reported more adherence strategies than the standard adherence and general health counseling conditions.

Discussion

Similar to past research, we observed poor ART adherence among persons with marginal and lower health literacy (18). To our knowledge this is the first randomized clinical trial of an ART adherence improvement intervention for people with poor literacy skills. We designed an intervention using established principles for enhancing health communication and education for medical patients with lower health literacy. (10, 27) The experimental ART counseling was guided by pictographic representations of HIV disease processes, actions of ART in suppressing HIV, and consequences of ART non-adherence. The intervention underwent extensive preliminary testing and demonstrated promising outcomes in a pilot study. (25) For participants with marginal levels of health literacy, the current findings failed to show any added benefit of the pictograph-guided counseling for adherence improvement beyond those observed from a standard approach to adherence counseling. Among participants with lower health literacy, neither the pictographic nor the standard adherence counseling demonstrated positive outcomes. This unexpected pattern of results suggests that individuals who demonstrate modest health literacy deficits can benefit from brief and focused adherence counseling. However, persons who experience more difficulty reading and understanding health information may require more intensive provider directed approaches to adherence.

The current trial was conducted in a city in the southeastern United States that may not be generalizable to other cities and regions. Generalizability was also limited by recruiting with outreach and referral procedures. Thus, while our sample extends across multiple clinics, our convenience sample cannot be considered representative of people living with HIV receiving care. Another limitation of the study was our use of self-reported measures of medication adherence strategies. The primary behavioral endpoint in this study was ART adherence measured by unannounced phone-based pill counts, which has not shown evidence of assessment reactivity. (37) Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the potential for monthly assessment calls prompting participant adherence across conditions. It is also possible that the literacy groups were confounded by unmeasured characteristics including neurocognitive disorders. In addition, we did not differentiate changes in viral load attributable to poor adherence from viral load increases resulting from treatment failure. With these limitations in mind, we believe that the current trial results have implications for HIV treatment adherence interventions for limited literacy adults.

HIV infections are most prevalent in low-income, disadvantaged communities. Poor health literacy likely plays a predominant role in HIV treatment outcomes and health disparities. (42) Results from the current study encourage screening patients for basic health literacy skills in risk assessments for difficulties adhering to treatment. Patients who do not experience difficulty reading as well as those who are less proficient readers may benefit from brief skills-based adherence counseling. However, patients who are unable to read and those who read with greater difficulty will require closer clinical monitoring and may benefit from more intensive approaches to adherence such as modified direct observation therapies, blister-packs, and mobile medication alert systems. (43) Literacy skills are associated with verbal memory, planning skills, motor speed and other neurocognitive functions that can all interfere with adherence. (44) Interventions are therefore still needed to achieve optimal ART adherence and positive treatment outcomes for patients with lower health literacy skills.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures and conflicts of interest:

This project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant R01-MH82633, Kalichman, PI. Detorio, Caliendo, and Schinazi were supported by the Center for AIDS Research, Emory University School of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P30 AI050409; Detorio and Schinazi were supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

No conflicts reported.

References

- 1.Bangsberg DR, Ragland K, Monk A, Deeks SG. A single tablet regimen is associated with higher adherence and viral suppression than multiple tablet regimens in HIV+ homeless and marginally housed people. AIDS. 2010;24(18):2835–40. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340a209. Epub 2010/11/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raboud J, Li M, Walmsley S, Cooper C, Blitz S, Bayoumi AM, et al. Once daily dosing improves adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1397–409. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9818-5. Epub 2010/09/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer DS. Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health promotion international. 2005;20(2):195–203. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah609. Epub 2005/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Majeed A, Car J. Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: A systematic review. Psychology, health & medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.701310. Epub 2012/07/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham J, Bennett IM, Holmes WC, Gross R. Medication beliefs as mediators of the health literacy-antiretroviral adherence relationship in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS and behavior. 2007;11(3):385–92. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9164-9. Epub 2006/10/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osborn CY, Davis TC, Bailey SC, Wolf MS. Health literacy in the context of HIV treatment: introducing the Brief Estimate of Health Knowledge and Action (BEHKA)-HIV version. AIDS and behavior. 2010;14(1):181–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9484-z. Epub 2008/11/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass PF, 3rd, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. American journal of health-system pharmacy : AJHP : official journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2006;63(11):1048–55. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050469. Epub 2006/05/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Osborn CY, Skripkauskas S, Bennett CL, Makoul G. Literacy, self-efficacy, and HIV medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.006. Epub 2006/11/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. Epub 2011/07/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkman ND, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP, Sheridan SL, Lohr KN, Lux L, et al. Literacy and health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2004 Summ;(87):1–8. Epub 2005/04/12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ownby RL. Medication adherence and health care literacy: filling in the gap between efficacy and effectiveness. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11920-005-0013-8. Epub 2005/02/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn CY, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Health literacy: an overlooked factor in understanding HIV health disparities. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;33(5):374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.022. Epub 2007/10/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waldrop-Valverde D, Jones DL, Jayaweera D, Gonzalez P, Romero J, Ownby RL. Gender differences in medication management capacity in HIV infection: the role of health literacy and numeracy. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):46–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9425-x. Epub 2008/07/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Functional health literacy is associated with health status and health-related knowledge in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(4):337–44. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200012010-00007. Epub 2000/12/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999;14(5):267–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. Epub 1999/05/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, Middlebrooks M, Kennen E, Baker DW, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21(8):847–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x. Epub 2006/08/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;145(12):887–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. Epub 2006/12/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paasche-Orlow MK, Cheng DM, Palepu A, Meli S, Faber V, Samet JH. Health literacy, antiretroviral adherence, and HIV-RNA suppression: a longitudinal perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):835–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00527.x. Epub 2006/08/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Servellen G, Carpio F, Lopez M, Garcia-Teague L, Herrera G, Monterrosa F, et al. Program to enhance health literacy and treatment adherence in low-income HIV-infected Latino men and women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17(11):581–94. doi: 10.1089/108729103322555971. Epub 2004/01/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khachani I, Harmouche H, Ammouri W, Rhoufrani F, Zerouali L, Abouqal R, et al. Impact of a Psychoeducative Intervention on Adherence to HAART among Low-Literacy Patients in a Resource-Limited Setting: The Case of an Arab Country--Morocco. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11(1):47–56. doi: 10.1177/1545109710397891. Epub 2011/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SA, Moore EJ. Health Literacy and Depression in the Context of Home Visitation. Maternal and child health journal. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0920-8. Epub 2011/11/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murri R, Cingolani A, De Luca A, Di Giambenedetto S, Marasca G, De Matteis G, et al. Asymmetry of the regimen is correlated to self-reported suboptimal adherence: results from AdUCSC, a cohort study on adherence in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(3):411–2. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ed1932. Epub 2010/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. Epub 1977/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. p. xv.p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalichman SC, Cherry J, Cain D. Nurse-delivered antiretroviral treatment adherence intervention for people with low literacy skills and living with HIV/AIDS. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC. 2005;16(5):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.07.001. Epub 2006/01/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jolly BT, Scott JL, Feied CF, Sanford SM. Functional illiteracy among emergency department patients: a preliminary study. Annals of emergency medicine. 1993;22(3):573–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81944-4. Epub 1993/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houts PS, Bachrach R, Witmer JT, Tringali CA, Bucher JA, Localio RA. Using pictographs to enhance recall of spoken medical instructions. Patient education and counseling. 1998;35(2):83–8. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00065-2. Epub 1999/02/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson TA, Thomas DM, Morton FJ, Offutt G, Shevlin J, Ray S. Use of a low-literacy patient education tool to enhance pneumococcal vaccination rates. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(7):646–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.646. Epub 1999/10/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. Epub 1995/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient education and counseling. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. Epub 2003/10/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amico KR, Barta W, Konkle-Parker DJ, Fisher JD, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, et al. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of ART adherence in a Deep South HIV+ clinic sample. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):66–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9311-y. Epub 2007/09/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):124–33. Epub 2000/04/13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Cherry C, Kalichman M, Pope H. Pillboxes and antiretroviral adherence: Prevalence of use, perceived benefits, and implications for electronic medication monitoring devices. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19:49–55. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Chesney M, Moss A. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:275–81. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Cherry C, Flanagan JA, Pope H, Eaton L, et al. Monitoring Antiretroviral adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: Reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clinical Trials. 2008;9:298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):841–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9597-z. Epub 2009/08/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Strebel A, Henda N, Kalichman SC, Cherry C, et al. HIV/AIDS risk reduction and domestic violence intervention for South African men: theoretical foundations, development, and test of concept. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2008;44(5):494–600. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Stearns H, White D, Flanagan J, Pope H, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1003–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0171-y. Epub 2007/03/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crepaz N, Lyles C, Wolitski R, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–57. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: a research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):285–97. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. Epub 2006/03/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jurs S, Glass G. The effect of experimental mortality on the internal and external validity of the randomized comparative experiment. Journal of Experimental Education. 1971;40:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):34–41. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499994. Epub 2010/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haberer JE, Kahane J, Kigozi I, Emenyonu N, Hunt P, Martin J, et al. Real-time adherence monitoring for HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1340–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9799-4. Epub 2010/09/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Wilkie FL, Mack A, Kumar M, Metsch L. Neurocognitive aspects of medication adherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):287–97. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9062-6. Epub 2006/02/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]