Abstract

Background

Meniscus tear patterns in the pediatric population have not been well described.

Hypothesis/Purpose

The purpose of this study was to delineate the pattern of meniscus tears and the likelihood of repair at the time of surgery in both children and adolescents.

Study Design

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods

Retrospective review was performed on all patients between the age of 10 and 19 years who underwent arthroscopic surgery for meniscus pathology. Patients were classified into two groups: those with open growth plates were classified as children while those with closed growth plates were classified as adolescents. Demographic data was documented, including: age, sex, BMI, mechanism of injury, and duration from injury to surgery. Operative reports and intraoperative photographs were used to assess tear pattern: type, location, zone, as well as all concomitant procedures and pathology. Tears were classified as discoid, vertical, bucket-handle, radial, oblique, horizontal, fray, root detachment, or complex. ANOVA and chi-squared tests were then performed.

Results

Of the 293 patients reviewed, 197 (67%) had lateral meniscus tears, 65 (22%) had medial meniscus tears, and 31 (11%) had tears to both menisci. The cohort was separated into groups: 119 (41%) children (open growth plates) and 174 (59%) adolescents (closed growth plates). The mean age between groups was 13.5 years compared to 16.4 years (p < 0.001), respectively. Children were more likely to have discoid meniscus tears, lower BMI, and meniscus pathology not associated with ligamentous injuries (p<0.05). The rate of associated ligament injuries in children was 29% compared to 51% in adolescents. Overall, the most frequent tear pattern was complex (28%) followed by vertical (16%), discoid (14%), bucket-handle (14%), radial (10%), horizontal (8%), oblique (5%), fray (3%), and root detachment (2%). Complex tears were associated with boys (32% vs. 20% girls, p < 0.03) and greater mean BMI (27.4 vs. 25.1 kg/m2, p < 0.002), even when taking sex into account. Surgical repair was performed in 46% of all cases (56% in those treated within 3 months of injury compared to 42% in those treated after 6 months (p<0.03) and there was no difference in repair rate based on patient age (46% vs 48%; p>0.05)).

Conclusions

Adolescents and children sustain more complex meniscus injuries that are often less repairable than previously reported in the literature. Factors that are associated with greater tear complexity include: male sex and obesity. Our findings also suggest that earlier treatment of meniscus tears may increase the likelihood of repair in younger patients.

Keywords: Meniscus tear, children, adolescents, repair

Introduction

With the rise of youth participation in athletics, an increasing number of meniscal tears have been seen in the pediatric and adolescent age groups.5, 25, 29 An estimated 80 to 90% of meniscal injuries are associated with athletic activity and are often seen in conjunction with other acute injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, chondral injuries, and tibial fractures.1, 29

The menisci are C-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures that are critical to shock absorption, load sharing, reduction of contact stresses, and stability within the knee joint.10, 14, 19, 21, 26 The importance of the menisci is apparent in complete or partial meniscectomies, where early osteoarthritic and degenerative changes are often seen.9, 27, 30 Anatomically, the meniscus is fully vascularized at birth, but the area of vascularity recedes toward the periphery with age; such that, by the age of 10, only the peripheral 10–30% of the meniscus is vascularized, as is seen in the adult meniscus.17, 18 The higher vascularity in the young meniscus and in the periphery of the adult meniscus have both been shown to provide better healing outcomes to surgical repair.3, 15

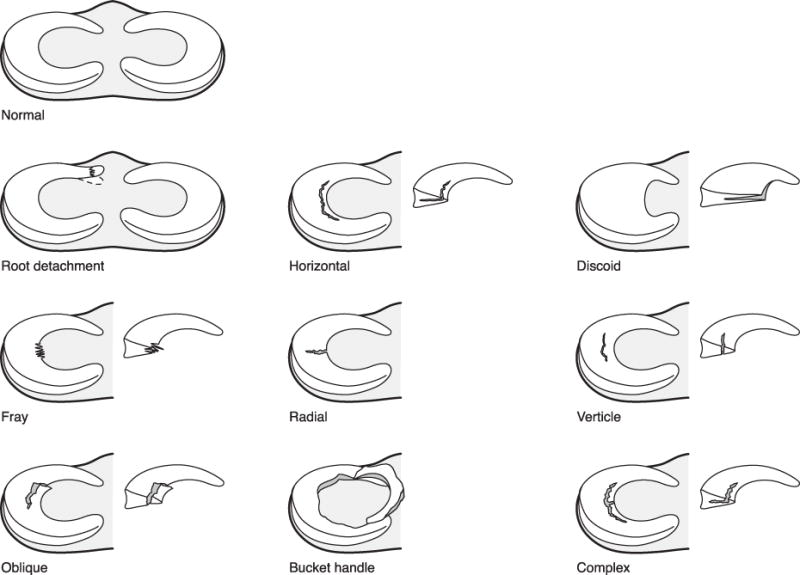

Tear patterns may be classified according to their orientation relative to the plane of the meniscus and the direction of collagen fibers.22, 28 All tears occur in one of two ways: horizontal or vertical. Horizontal tears represent axial plane tears parallel to the articular joint surface. Vertical tears can occur in a longitudinal, transverse, or mixed fashion and as such are further divided into the sub-categories: longitudinal, radial, and oblique. Longer and complete tears are often displaceable and are commonly referred to as “bucket-handle” tears due to their resemblance in shape and ability to flip into the notch. Tears with multiple components are referred to as complex.

The surgical approach to meniscal tears is typically determined by the type of the tear in conjunction with the tear location, patient age, and the chronicity of the tear. Longitudinal vertical and bucket-handle tears are often able to be repaired surgically with various suturing techniques while radial, oblique, horizontal, and complex tears do not respond as well to surgical repair.6 Meniscal tear patterns have been well characterized in the adult population, but extensive studies have not been performed on the pediatric and adolescent populations. Previous studies have found that young patients typically present with longitudinal vertical (50–90%) and bucket-handle meniscal tears to the medial meniscus.2, 11, 13, 17 However, differences in meniscus tears that occur in children who are skeletally immature and tears that occur in adolescent patients that are skeletally mature have not been previously elucidated. The purpose of this study was to describe meniscus tear patterns and to assess the incidence of repair during surgery in these two youthful groups.

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, a retrospective chart review of all pediatric and adolescent patients between the ages of 10 and 19 who underwent arthroscopic knee surgery for meniscus pathology at our institution between October 2008 and July 2012 was performed. After imposing the exclusion criterion of a previous meniscus procedure, they were classified as child or adolescent based on skeletal maturity as determined by X-rays and MRIs taken when patients first presented to clinic. Those with open growth plates were classified as children while those with closed growth plates were classified as adolescents. Demographic data was documented, including sex, age and BMI at time of surgery, and duration from injury to surgery. Operative reports and intraoperative photographs were used to assess tear pattern and location, as well as all concomitant procedures and pathology. Tear patterns were classified in the following categories: discoid, vertical, bucket-handle, radial, oblique (parrot beak), horizontal, fray, root detachment, or complex. (Fig. 1) Patients who were treated within three months of injury were considered to have an acute injury while those treated after six months were considered chronic. To more accurately differentiate acute and chronic tears, those treated between 3 to 6 months from injury were not included in either chronicity group because injury dates were often estimated by patients or family members. Ninety-three patients fell into this subacute group. Tears with no evidence of peripheral instability upon probing, measuring less than 1 cm, and/or incomplete were considered stable and were excluded from repair rate calculations. ANOVA and chi-squared tests were performed with a significance set at p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Meniscal tear classification.

Results

A total of 293 patients (186 boys and 107 girls) were included in the study: 153 had surgery on their left knee while 140 had surgery on their right (52% vs. 48%, p<0.45). There were 197 patients (67%) with lesions of the lateral meniscus, 65 (22%) with lesions of the medial meniscus, and 31 (11%) with lesions of both menisci, giving a total of 324 torn menisci.

Based on physeal status (open versus closed), closed), 119 (59%) were defined as children with open growth plates while 174 (41%) were defined as adolescents with closed growth plates. Children had lower mean age (13.5 vs. 16.4 years, p < 0.001) and mean BMI (23.0 vs. 27.5 kg/m2, p < 0.01) than adolescents. Discoid meniscus tears accounted for 25% of all tears in children, but only 7% of tears in adolescents (p < 0.0001). Concomitant ligament injury was observed in 51% of adolescents compared to 28% of children (p < 0.0001). The ACL was involved in 96% of all ligamentous injuries. One patient had an associated tibial spine fracture. There were no significant differences in meniscal tear complexity, location, zone, or surgeon-determined ability to repair the tear between the two groups.

However, when assessing the associated injuries within the children and adolescent groups, a few differences were identified. Among children, complex tears were associated with the boys (32% vs. 10% in girls, p < 0.01). Among the adolescent population, decreased repair rates were associated with boys (41% vs. 56% in girls, p < 0.04) and chronic tears (37% vs. 58% in acute, p < 0.03).

There were 46 discoid tears, representing 14% of the cohort, and all of these involved the lateral meniscus. One of these patients also had a vertical tear to the medial meniscus. Children accounted for 71% of all discoid tears and 41% required repair along the periphery after saucerization. Patients with discoid tears had a lower mean age (12.7) than that of non-discoid tears (15.7) (p<0.0001) with a lower mean BMI (22.1 vs. 26.5 kg/m2, p<0.0001) and a female preponderance (56% to 44%, p<0.23).

The most frequent tear pattern was complex (28%) followed by vertical (16%), discoid (14%), bucket-handle (14%), radial (10%), horizontal (8%), oblique (5%), fray (3%), and root detachment (2%) (Table 1). Complex tears were associated with boys (32% vs. 20% girls, p < 0.03) and greater mean BMI (27.4 vs. 25.1 kg/m2, p < 0.002), even when taking sex into account.

Table 1.

Patient data

| Type | Children | Adolescents | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 119 (41%) | 174 (59%) | 293 (100%) | ||

| Meniscus tears | 126 (39%) | 198 (61%) | 324 (100%) | ||

| Patients with associated ligament injury | 33 (28%) | 89 (51%) | 122 (42%) | ||

| Discoid | 32 (25%) | 14 (7%) | 46 (14%) | ||

| # of Complex meniscus tears | 31 (25%) | 60 (30%) | 91 (28%) | ||

| Meniscus repair rates | 59 (49%) | 89 (46%) | 148 (47%) | ||

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | ||

| Complex tears | 27 (32%) | 4 (10%) | 40 (33%) | 20 (27%) | 91 (28%) |

| Repair rates | 41 (51%) | 18 (45%) | 49 (41%) | 40 (56%) | 148 (47%) |

| Acute | Chronic | Acute | Chronic | ||

| Complex tears | 14 (29%) | 10 (21%) | 22 (29%) | 21 (36%) | 67 (29%) |

| Repair rates | 25 (53%) | 21 (46%) | 43 (58%) | 21 (37%) | 110 (49%) |

The posterior horn was involved in 71% of the tears, the body in 50%, and the anterior horn in 23%. Ligamentous injury primarily involving the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) was visualized arthroscopically in 45% of all patients, and of these, 54% had pathology to the lateral meniscus, 25% to the medial, and 21% to both. In comparison, in patients without ligamentous injury, 77% had pathology to the lateral meniscus, 20% to the medial, and 4% to both. Surgical repair was performed in 46% of cases, partial menisectomy was performed in 51%, and 4% were stable tears that the surgeon felt did not require intervention. All, but one, of the 11 stable tears were vertical. A majority of root detachment, vertical, bucket-handle, and horizontal tears were repairable, while a minority of complex tears were repaired. None of the radial, oblique or fray tear patterns were repaired. Repair rates dropped from 56% in patients treated within 3 months to 42% in patients treated after 6 months (p<0.03). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Meniscal tear types in children and adolescents

| Type | Children | Adolescents | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | 31 (25%) | 60 (30%) | 91 (28%) |

| Vertical | 16 (13%) | 37 (19%) | 53 (16%) |

| Discoid | 32 (25%) | 14 (7%) | 46 (14%) |

| Bucket-handle | 13 (10%) | 32 (16%) | 45 (14%) |

| Radial | 9 (7%) | 22 (11%) | 31 (10%) |

| Horizontal | 13 (10%) | 13 (7%) | 26 (8%) |

| Oblique | 4 (3%) | 14 (7%) | 18 (6%) |

| Fray | 6 (5%) | 3 (2%) | 9 (3%) |

| Root detachment | 2 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 5 (2%) |

| Total | 126 | 198 | 324 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe meniscal tear patterns in the pediatric and adolescent populations. Previous studies in this population have shown that peripheral longitudinal and bucket-handle tears were most frequent along with a predominance of medial meniscus tears.11, 16, 29 In contrast, our results suggest that meniscus tears more often affect the lateral meniscus than the medial and are also more likely to be complex in the age groups we studied. Furthermore, complex tears were more likely to occur in boys and those with higher BMI.

As expected, discoid menisci are predominantly seen in the lateral meniscus and primarily affect skeletally immature children. Adolescents were more likely to have concurrent ligamentous injuries, which might be explained in part by the increased participation in competitive sports of that age group. There were no significant differences in meniscus tear type, location, or zone between the two groups, and more importantly, the repair rate was similar in the two groups. Therefore, clinicians should expect to find more discoid menisci in children and ligament injuries in adolescents but similar tear patterns and repair rates in both.

Breaking down the two age groups further, it appears that adolescent boys and those treated after six months from injury had lower rates of repair. Among children, boys were more likely to have complex meniscal tears, which inherently have lower repair rates. However, because children also present with more discoid and repairable tears, repair rates were not significantly lower in this group.

Lawrence et al. recently reported that skeletally immature patients with ACL tears who underwent surgical reconstruction more than 12 weeks after the injury had significantly more irreparable meniscus pathology.20 Similarly, our study showed a significant association between irreparable meniscal tears and longer time from injury to surgery. Patients treated within 3 months after injury had a 56% rate of repair compared to 42% in the group treated more than 6 months from injury. In adolescents, the repair rate dropped from 58% to 37%, indicating that earlier surgical intervention may increase the likelihood of repair in younger patients, especially in adolescent boys.

In the adult population, meniscus tears are associated with acute ACL injuries, but to varying degrees. Studies have shown that meniscus tears may occur in 33% to 65% of patients with acute ACL injuries.8, 12, 24, 31 There is also little agreement on the frequency of tears to the lateral versus medial meniscus, ranging from 56% medial7, 12 to 65% lateral23. In acute ACL tears, lateral meniscus tears occur about 56% of the time4. Our study instead focused on all patients who were found to have meniscus tears, with the data showing that over 45% of all patients with meniscus tears also had a ligament injury. Most of the patients with ligament injury were adolescents, and the lateral meniscus was more frequently involved, though this number was decreased from the group without ligament injury.

There were a few limitations to this study. The intraoperative assessment of tear types, as well as the determination of ability to repair the tear was subject to assessment by the operating surgeon. Patient BMI was based on height and weight on the date of surgery rather than the date of injury. Injury history, including mechanism of injury and time to surgery, for each patient was based on estimates provided by the patients and their families, as recorded at the initial visit. However, most of these limitations are basic flaws to a retrospective study design and only a prospective study could have potentially generated more accurate and complete information.

As acute knee injuries become more frequent with increased participation in recreational and competitive youth sports, the ability to repair such injuries becomes even more important for long-term joint health. This study has provided meniscal tear data on a large sample size that we believe reflects current knee injury trends in youth sports. Meniscus tears in adolescent and pediatric patients are more complex, preferentially affect the lateral meniscus, and are often less repairable than previously reported in the literature. Factors associated with greater tear complexity include male sex and obesity. Skeletally mature adolescents are more likely to present with concomitant ligament tears while skeletally immature children more often present with a discoid meniscus; but, both groups are affected by the same meniscal tear patterns. The ability to repair meniscal tears was significantly lower in patients treated after six months from injury, especially in male adolescents. The data suggest that earlier surgical intervention in pediatric and adolescent patients may result in greater repair rates of meniscus tears.

Table 3.

Meniscal repair rates

| Type* | Children | Adolescent | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Repaired | Stable | Repaired (% of tear type) | Not Repaired | Stable | Repaired (% of tear type) | Repaired (% of tear type) | |

| Complex | 18 | – | 13 (42%) | 37 | – | 23 (38%) | 36 (40%) |

| Vertical | 1 | 4 | 11 (92%) | 6 | 6 | 25 (81%) | 36 (84%) |

| Discoid | 18 | – | 14 (44%) | 9 | – | 5 (36%) | 19 (41%) |

| Bucket-handle | 3 | – | 10 (77%) | 11 | – | 21 (66%) | 31 (69%) |

| Radial | 9 | – | 22 | – | – | 0 (0%) | |

| Horizontal | 3 | 1 | 9 (75%) | 1 | – | 12 (92%) | 21 (84%) |

| Oblique | 4 | – | – | 14 | – | – | 0 (0%) |

| Fray | 6 | – | – | 3 | – | – | 0 (0%) |

| Root detachment | – | – | 2 (100%) | – | – | 3 (100%) | 5 (100%) |

| Total | 62 | 5 | 59 (49%) | 103 | 6 | 89 (46%) | 148 (47%) |

Repair percentages excluded stable tears

What is known about the subject

Meniscus tear patterns in adults have been well described in the literature, but little is known about tear patterns in children and adolescents.

What this study adds to existing knowledge

This study describes meniscus tear patterns assessed arthroscopically in a large cohort of pediatric patients revealing that a large number of these tears are more complex and less repairable than previously reported.

References

- 1.Andrish JT. Meniscal Injuries in Children and Adolescents: Diagnosis and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996 Oct;4(5):231–7. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel KR, Hall DJ. The role of arthroscopy in children and adolescents. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(3):192–6. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(89)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. Microvasculature of the Human Meniscus. Am J Sport Med. 1982;10(2):90–5. doi: 10.1177/036354658201000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR., Jr Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate-deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1997;26(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellisari G, Samora W, Klingele K. Meniscus tears in children. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2011 Mar;19(1):50–5. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318204d01a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown TD, Davis JT. Meniscal injury in the skeletally immature patient. In: Micheli LJ, Kocher MS, editors. The Pediatric and Adolescent Knee. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 236–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerabona F, Sherman MF, Bonamo JR, Sklar J. Patterns of meniscal injury with acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(6):603–9. doi: 10.1177/036354658801600609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeHaven KE. Diagnosis of acute knee injuries with hemarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(1):9–14. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948 Nov;30B(4):664–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fithian DC, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties and structure-function relationships in the menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990 Mar;(252):19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu F, Baratz M. Meniscal injuries. In: DeLee JC, Drez DJ, editors. Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994. pp. 1146–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilcoyne KG, Dickens JF, Haniuk E, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Epidemiology of meniscal injury associated with ACL tears in young athletes. Orthopedics. 2012;35(3):208–12. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120222-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King AG. Meniscal lesions in children and adolescents: a review of the pathology and clinical presentation. Injury. 1983 Sep;15(2):105–8. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(83)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King D. The function of semilunar cartilages. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1936 Oct 01;18(4):1069–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King D. The healing of semilunar cartilages. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936;18:333–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocher MS. The pediatric knee: Evaluation and treatment. In: Insall JN, Scott WN, editors. Surgery of the Knee. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 2001. pp. 1356–97. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocher MS, Klingele K. Meniscal Disorders. In: Insall JN, Scott WN, editors. Surgery of the Knee. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 1223–1233. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer DE, Micheli LJ. Meniscal Tears and Discoid Meniscus in Children: Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Sur. 2009 Nov;17(11):698–707. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause WR, Pope MH, Johnson RJ, Wilder DG. Mechanical changes in the knee after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976 Jul;58(5):599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrence JTR, Argawal N, Ganley TJ. Degeneration of the knee joint in skeletally immature patients with a diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament tear: is there harm in delay of treatment? Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(12):2582–7. doi: 10.1177/0363546511420818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy IM, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The effect of medial meniscectomy on anterior-posterior motion of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982 Jul;64(6):883–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalf MH, Barrett GR. Meniscectomy. In: Callaghan JJ, Rosenberg AG, Rubash HE, Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, editors. The Adult Knee. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. pp. 585–606. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paletta GA, Jr, Levine DS, O’Brien SJ, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Patterns of meniscal injury associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament injury in skiers. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(5):542–7. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poehling GG, Ruch DS, Chabon SJ. The landscape of meniscal injuries. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(3):539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purvis JM, Burke RG. Recreational injuries in children: incidence and prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001 Nov-Dec;9(6):365–74. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radin EL, de Lamotte F, Maquet P. Role of the menisci in the distribution of stress in the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984 May;(185):290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rangger C, Klestil T, Gloetzer W, Kemmler G, Benedetto KP. Osteoarthritis after Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy. Am J Sport Med. 1995 Mar-Apr;23(2):240–4. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg TD, Kolowich PA. Arthroscopic diagnosis and treatment of meniscal disorders. In: Scott WN, editor. Arthroscopy of the Knee. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanitski CL, Harvell JC, Fu F. Observations on acute knee hemarthrosis in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993 Jul-Aug;13(4):506–10. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vahvanen V, Aalto K. Meniscectomy in Children. Acta Orthop Scand. 1979;50(6):791–5. doi: 10.3109/17453677908991311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren RF, Levy IM. Meniscal lesions associated with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1983;(172):32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]