Abstract

Context

The death of a child from cancer affects the entire family. Little is known about the long-term psychosocial outcomes of bereaved siblings.

Objectives

To describe: (1) the prevalence of risky health-behaviors, psychological distress, and social support among bereaved siblings; (2) potentially modifiable factors associated with poor outcomes.

Methods

Bereaved siblings were eligible for this dual-center, cross-sectional, survey-based study if they were ≥16 years-old and their parents had enrolled in one of three prior studies about caring for children with cancer at end of life. Linear regression models identified associations between personal perspectives before, during, and after the family's cancer experience and outcomes (health-behaviors, psychological distress, and social support).

Results

Fifty-eight siblings completed surveys (62% response rate). They were approximately 12 years bereaved, with a mean age of 26 years at the time of the survey (SD=7.8). Anxiety, depression, and illicit substance use increased during the year following their brother/sister's death, but then returned to baseline. Siblings who reported dissatisfaction with communication, poor preparation for death, missed opportunities to say “goodbye,” and/or a perceived negative impact of the cancer experience on relationships tended to have higher distress and lower social support scores (p<0.001-0.031). Almost all siblings reported their loss still affected them; half stated the experience impacted current educational and career goals.

Conclusion

How siblings experience the death of a child with cancer may impact their long-term psychosocial well-being. Sibling-directed communication and concurrent supportive care during the cancer experience and the year following sibling death may mitigate poor long-term outcomes.

Keywords: bereavement, siblings, pediatric cancer, psychological distress, resilience, psychosocial outcomes, survivorship

INTRODUCTION

Childhood cancer is a family illness[1-8]. The demands of treatment may be highly disruptive not only to parents, but also to siblings in the home. When children die from their cancer, the impact on the family may be profound. A growing body of literature has focused on psychosocial outcomes among bereaved parents[9], but comparatively few studies have described the perspectives and outcomes of bereaved siblings of children with cancer.

The potential negative impact of cancer on healthy siblings is self-evident; they receive less attention from parents and commonly report feelings of loneliness, sadness, anger, jealousy, anxiety, and guilt[10]. While most non-bereaved siblings ultimately recover from the emotional distress of their cancer experience, a significant subset endorse post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, depressed mood, poor quality of life, and diminished social support[8].

Studies conducted within the first year of bereavement suggest that almost all bereaved siblings report changes in perspectives, interests, and relationships, and these are often indicative of personal growth, new meaning, or purpose[11]. Peer relationships during the 3-12 month after a siblings death may be differentially affected by age, however; school-aged bereaved boys tend to be perceived as sensitive, isolated, or victimized by their peers, but bereaved adolescents may be seen as popular or as leaders[12].

Longer-term, one large Swedish cohort study of bereaved siblings up to 9 years after death from cancer identified increased risk of low self-esteem, low maturity, and sleep difficulties compared to population norms[13], and only 11% reported having completely worked through their grief[14]. Siblings’ long-term outcomes may be related to their experiences during and immediately after brother or sister's cancer treatment; many are dissatisfied with the information their receive from parents or health-care professionals[15,16], and their lack of involvement may translate to impaired bereavement, negative emotional reactions, and school difficulties[8,17].

Better understanding of the relationships between identifiable risk factors (e.g., age), elements of the cancer experience (e.g., communication), and long-term outcomes may provide opportunities for intervention. The objective of this study was to (1) describe long-term psychosocial outcomes (e.g., risky health-behaviors, psychological distress, and social support) among bereaved siblings (2) explore potentially modifiable factors of poor long-term psychosocial outcomes, including the role of the medical team in facilitating end-of-life communication.

METHODS

“To Lose a Sibling” was a dual-center, cross-sectional, survey-based study of siblings whose brother or sister had died from pediatric cancer between 1990 and 2004 and whose bereaved parents had participated in one of three earlier studies conducted at Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center (DF/BCCDC) and Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota (CHC)[18-24]. Siblings were enrolled from March 2008 to July 2009. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both centers.

Participants

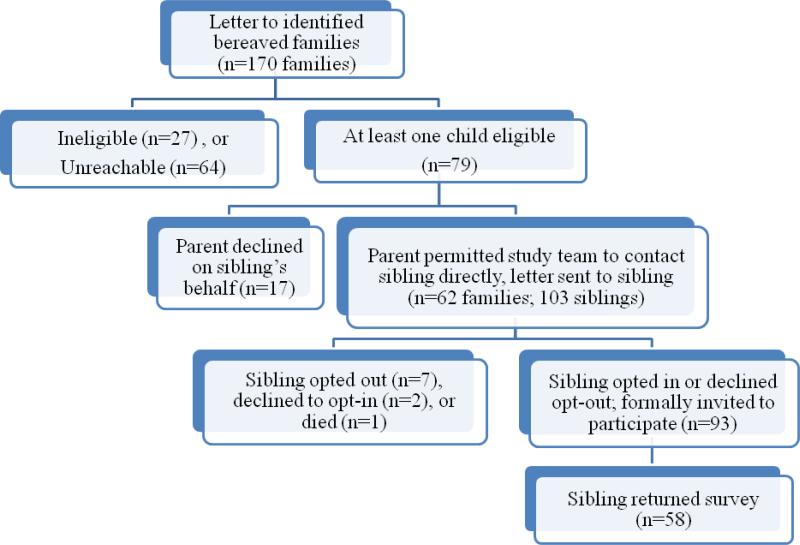

Bereaved siblings were defined as other children living in the home during the family's cancer experience. Full-, half- and adopted siblings were eligible to participate if they were at least 16 years old at the time of enrollment and had written command of the English language. They could have been any age during the cancer experience and there was no upper age limit for participation. They were approached as follows. First, the bereaved parents who participated in the above mentioned studies and had indicated they had other living children were sent an introductory letter with stamped opt-in/out cards (Figure 1). Opt-in/out cards were used to verify eligibility and willingness to participate, and to get siblings’ contact information. A follow-up phone call was made two weeks later, for families who did not answer the letter. Participating siblings ages 18 or older were required to return a signed opt-in card; siblings 16-17 had to provide verbal/signed assent and their parents a signed opt-in card. Once participation was confirmed, we mailed the survey packet with a stamped return envelope. Two reminder phone calls were in place at weeks 2 and 4 after the first mailing. All participating siblings received a thank you card.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Survey Instruments

The Survey for Bereaved Siblings (SBS) used in this study was adapted from the one developed for the Swedish Cohort Study[25,26]. The original survey was iteratively pre-tested and piloted, and was used in a recent study designed to assess the grief processes of bereaved siblings.[14] An adaption team included three bereaved parents, a bereaved sibling and members of the study team (UK, JW and VD). De novo items were developed using an evidence-based, step-wise approach[13,14,27] and validated subscales were used to measure general psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and social support. Once developed, the SBS was pre-tested and validated by content experts and through interviews with an additional three bereaved siblings to assess content, response burden, and cognitive validity.

Risky Health Behaviors and Emotional Well-Being

The SBS queries bereaved siblings’ health behaviors and emotional well-being at several time-points: (1) during the year before their sibling's diagnosis with cancer; (2) during their sibling's illness; (3) at the time of their sibling's death; (4) during the year immediately after their sibling's death, and; (5) currently. Risky health behaviors were assessed with a 5-point Likert scale gauging the frequency of illegal drug-use and alcohol intake at each time-point. For the present analyses, we defined any illegal drug use as “risky” and collapsed responses to “never” versus “rarely/regularly/most days/daily.” We defined alcohol consumption as “risky” only if participants endorsed at least regular drinking “to the point of being drunk”; responses were collapsed to “never/rarely” versus “regularly/most days/daily.”

The SBS measures current global psychological distress with the Kessler-6 (K6) psychological distress scale. This well-validated, 6-item scale is used by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to measure population level mental health[28]. It has excellent discriminatory properties as a screen, in particular for anxiety and depression[29]. The instrument asks, “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel: (a) nervous; (b) hopeless; (c) restless or fidgety; (d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up; (e) that everything was an effort; and (f) worthless.” Reponses options are scored on a Likert scale of “none of the time,” “a little of the time,” “some of the time,” and “all of the time.” Total scores range from 0 to 24; higher scores suggest greater distress and scores of 7 or more indicate “high” distress. The average K6 score among US adults is 2.5[29]. Self-reported feelings of anxiety and depression are measured with a visual-digital scale, where participants are asked to select the number (between 1 and 10, 10 being the highest) which best describes their degree of anxiety or depression during each time period[30].

Demographics and Social Support

Additional items query current demographic characteristics and social support. The latter is measured with the social support survey of the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS)[31]. This 9-item survey assesses functional dimensions of general social support including emotional, informational, and interactive domains. For example, the survey asks “How often is each of the following kinds of support available to you if you need it?” Items then include “someone to help you if you were confined to bed,” “someone who shows you love and affection,” and “someone to confide in or talk to about yourself or your problems.” Likert scale options are “none of the time,” “ a little of the time,” some of the time,” “ most of the time,” and “all of the time.” Total scores are summed and then transformed to a 100-point scale, with higher scores indicative of greater social support. The average MOS social support score among US adults is 70.1[31].

Perceptions of the Illness Experience

Finally, the SBS queries siblings’ perceptions of the illness experience at the same 5 time points. Specific items address perceived communication and involvement within the family and medical team. For example, siblings are asked if they were satisfied with the information provided by their parents and health care staff, and if they had an opportunity to say “goodbye.” Likewise, items address the overall impact of losing a sibling to cancer. For example, siblings are asked if their loss continues to affect them, if they perceive themselves to be more mature than others their age, and if/how their sibling's death has affected their social, educational, and professional experiences.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with the Stata 12 software package (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize bereaved respondents and their deceased siblings. Means and standard deviations (SD) were used for continuous variables when data distribution was close to normal, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) otherwise. Frequencies and percents were used for categorical variables. To describe changes in health behaviors and anxiety/depression over time, we limited analyses to those siblings who had provided responses for all time-points. Simple linear regression models were fitted to determine relationships between independent variables (demographic characteristics, perceptions of the cancer experience) and outcome variables (current psychological distress or social support). Multivariable linear regression models adjusted for covariates such as study-site, same-family siblings, age at diagnosis, current age, sex, time since sibling's death, education, employment, marital status, and type of cancer. Point estimates from adjusted models were similar to those from simple models; hence, results from simpler models are presented here. For all analyses, we used a two-sided alpha of 0.05.

RESULTS

Response Rate and Participant Characteristics

From the original studies, we identified 196 families with other living children and sent 170 (87%) introductory letters to those with valid contact information (Figure 1). Of these, 79 (46%) families had at least one child that met eligibility criteria, 27 (16%) had all ineligible children, and 64 (38%) were unreachable. Seventeen parents declined participation of their children (all from DF/BCCDC cohorts, CHC did not give the option to parents of adult siblings), resulting in 62 families with 103 potential sibling-participants. A total of 93 surveys were mailed (2 siblings did not send the opt-in card, 1 died during the process, and 7 had opted out). Fifty-eight siblings from 46 families returned surveys (62% of all who received a mail survey).

At the time of the survey, respondents’ mean age was 25.6 years (SD=7.8) and 11.8 years had passed since their sibling's death (SD=3.2, Table 1). Respondents were predominantly white females with at least some college-level education. Most were currently employed or in school and 41% were living with their parents. The mean age of their deceased siblings at the time of death was 12.8 years (SD=6.2). Approximately half died from hematologic malignancies.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of bereaved respondents and their siblings

| BEREAVED RESPONDENTS (N=58) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Range | |

| Age at time of survey (years) | 25.6 | (7.8) | 18-46 |

| Age at sibling's diagnosis of cancer (years) | 10.9 | (6.2) | 0-23 |

| Age at sibling's death (years) | 13.8 | (7.3) | 1-31 |

| Time since sibling's death (years) | 11.8 | (3.2) | 5-17 |

| n | (%) | ||

| Younger than sibling at time of diagnosis | 26 | (46) | |

| Sex | n | (%) | |

| Female | 40 | (69) | |

| Male | 18 | (31) | |

| Same sex as deceased | 29 | (50) | |

| Relationship | |||

| Full sibling | 49 | (84) | |

| Half-sibling | 8 | (14) | |

| Adopted sibling | 1 | (2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | n | (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 56 | 97 | |

| Other* | 2 | 3 | |

| Highest level of education | n | (%) | |

| High School | 24 | (41) | |

| College, Trade- or graduate-school | 34 | (59) | |

| Current employment status | n | (%) | |

| Employed | 25 | (43) | |

| Student | 26 | (45) | |

| Unemployed | 7 | (12) | |

| Marital status | n | (%) | |

| Married or living with partner | 21 | (36) | |

| Living with parents | 24 | (41) | |

| Living independently | 13 | (23) | |

| DECEASED SIBLINGS (N=46) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Range | |

| Age at diagnosis of cancer | 10.6 | (5.6) | 0-19 |

| Age at death | 12.8 | (6.2) | 0-23 |

| Cancer type | n | (%) | |

| Hematologic Malignancy | 22 | (48)† | |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) tumor | 14 | (30)† | |

| Non-CNS solid tumor | 8 | (17)† | |

| Don't know | 2 | (4)† | |

1 Non-Hispanic Black, 1 Native American/Pacific Islander

Percents do not add to 100% due to rounding

Risky Health Behaviors and Emotional Well-Being

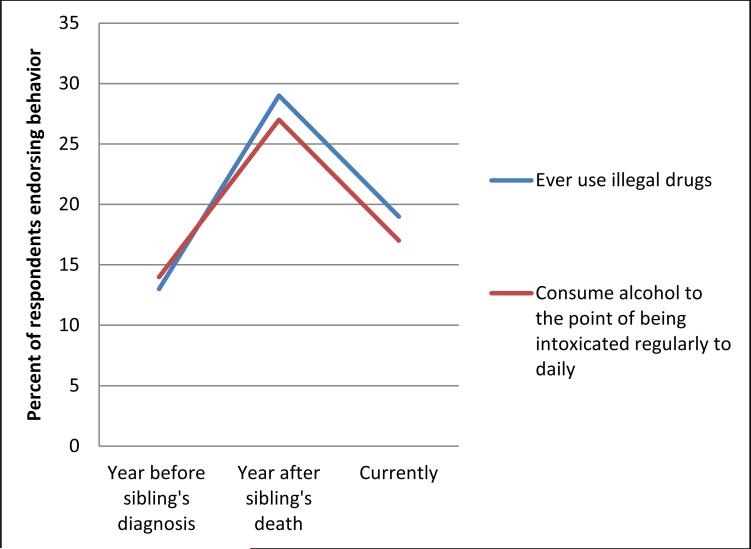

Thirty-eight and thirty-seven respondents had complete data regarding drug and alcohol use at all three time points, respectively. They reported higher illegal drug and alcohol use during the year immediately after their sibling's death than prior to their sibling's diagnosis. Although these behaviors returned to near baseline at the end of the survey, 11 (19%) reported using any illegal drugs and 10 (17%) reported being intoxicated from alcohol during the month prior to completing the survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bereaved siblings’ reported use of illegal drugs and alcohol over time. (n=38 with item-response for illegal drug use at all three time points, n=37 with item-response for alcohol consumption at all three time-points).

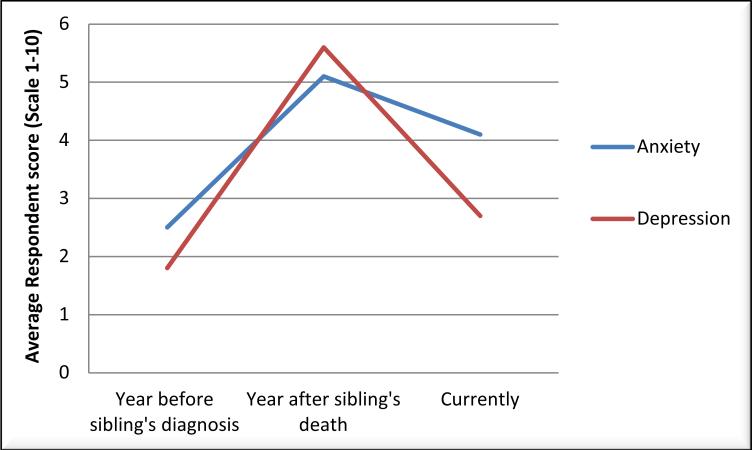

A similar pattern was observed in respondents’ trajectories of anxiety and depression, although slightly more reported current anxiety (Figure 3). While most K6 scores indicated no current psychological distress (median=3, IQR 2,6), approximately a quarter of respondents (n=13, 23%) had scores consistent with current “high” distress. Several elements of the cancer experience were associated with increased K6 scores. For example, bereaved respondents who reported that their peer relationships were negatively impacted by their sibling's cancer had K6 scores an average of 4.3 points higher (p=0.001, Table 2). Likewise, those who were unsatisfied (versus satisfied) with their parents’ or health care teams’ communication of information, those who were unprepared (versus prepared) for their sibling's death, those who were unable (versus able) to say “goodbye” and those who had not (versus had) completely worked through their grief all had higher distress scores (β=2.2 to 3.4, p<0.001-0.025).

Figure 3.

Bereaved siblings’ self-assessment of anxiety and depression over time (scale of 1-10, with 10 being highest anxiety/depression). (n=40 with anxiety item-response at all three time points, n=39 with depression item-response at all time points).

Table 2.

Average change in bereaved sibling psychological distress and social support scores given perceived factors of illness experience

| Psychological Distress | Social Support | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | |

| During the Illness Experience | |||||

| Age at the time of sibling's diagnosis of cancer | |||||

| 13 years or older | 24 (43) | −0.4 (−2.4, 1.6) | 0.675 | −22.7 (−41.4, −4.1) | 0.018 |

| 12 years and under | 29 (52) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| “To what extent were your relationships with others negatively impacted during your sibling's illness?” (n=49) | |||||

| “A lot”/“A great deal” | 9 (18) | 4.3 (1.8, 6.8) | 0.001 | −45.4 (−29.5, −61.3) | <0.001 |

| “Somewhat”/“A little”/“Not at all” | 40 (82) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| “Were you satisfied with the amount of information you received from your parents during your sibling's last month of life?” (n=51) | |||||

| No | 10 (20) | 3.4 (1.1, 5.7) | 0.004 | −45.7 (−31.3, −60.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 41 (80) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| “Were you satisfied with the amount of information you received from health care staff?” (n=43) | |||||

| No | 11 (26) | 3.7 (1.0, 6.4) | 0.008 | −40.2 (−23.4, −57.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 32 (74) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| At the time of sibling's death | |||||

| “Did you feel prepared for the circumstances at the time of your sibling's death?” (n=52) | |||||

| “Not at all”/“A little”/“To a certain extent” | 43 (83) | 2.6 (0.7, 4.5) | 0.009 | −22.8 (−2.1, −43.5) | 0.031 |

| “Yes, completely” | 9 (17) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| “Did you have the opportunity to say ‘goodbye’ to your sibling in a comfortable manner?” (n=53) | |||||

| “Not at all”/“A little”/“To a certain extent” | 27 (51) | 2.2 (0.3, 4.0) | 0.025 | −17.9 (−36.4 ,0.8 | 0.059 |

| “Yes, completely” | 26 (49) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

| After the sibling's death | |||||

| “Do you feel that you have worked through your grief?” (n=54) | |||||

| “Not at all”/“Somewhat”/“A lot” | 41 (76) | 3.4 (1.9, 4.9) | <0.001 | −8.6 (−27.7, 10.4) | 0.364 |

| “Completely | 13 (24) | (ref) | -- | (ref) | -- |

Social Support

The median social support score was 75 (IQR 28,91). Similar perceptions of the illness experience were associated with decreased current social support. For example, those who reported a negative impact on their relationships with others had average social support scores 45 points lower than those whose relationships were not impacted negatively (p<0.001, Table 2). Those who were unsatisfied with received information or who felt unprepared for their sibling's death also had lower social support scores (β =-22.8 to -45.7, p<0.001-0.031). In addition, bereaved respondents who were 13 years or older at the time of their sibling's diagnosis reported lower current social support than those who were younger than 13 years (β=-22.7, p=0.018).

Perceptions of the Illness Experience

Almost all respondents (88%) reported that the loss of their sibling continued to affect their lives (Table 3). Personal growth was reported in subsets of cases; 36%, reported that they were better communicators, 43% more mature, 45% more kindhearted, and 17% more confident than others their age. Approximately half reported that their sibling's death had impacted education and career choices. For example, 12% reported that their experience had negatively impacted their work/career while 45% reported a positive impact on work/career. None of these responses (personal growth, impact on education/career) were related to current distress or social support.

Table 3.

Effect of sibling's death on perspectives of life, education, and career

| Overall Perspectives (N=58) | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| “Do you feel that the loss of your brother or sister continues to affect your life?” | ||

| Yes | 51 | (88) |

| No | 7 | (12) |

| “I am a better communicator than most people my age” (n=56) | ||

| “Agree”/“Strongly Agree” | 20 | (36) |

| “Disagree”/“Strongly Disagree” | 38 | (64) |

| “I am more mature than most people my age” (n=55) | ||

| “Agree”/“Strongly Agree” | 22 | (43) |

| “Disagree”/“Strongly Disagree” | 29 | (57) |

| “I am more kindhearted than most people my age” | ||

| “Agree”/“Strongly Agree” | 26 | (45) |

| “Disagree”/“Strongly Disagree” | 32 | (55) |

| “I am more confident than most people my age” (n=48) | ||

| “Agree”/“Strongly Agree” | 8 | (17) |

| “Disagree”/“Strongly Disagree” | 40 | (83) |

| Education and Career (N=58) | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| “Did the death of your sibling impact any choices you made regarding your educational and career goals?” | ||

| “Somewhat”/“A lot”/“A great deal” | 28 | (48) |

| “Not at all”/“A little” | 30 | (52) |

| “Overall, do you believe your schoolwork has been affected negatively by your experience having lost a sister or brother to cancer?” | ||

| “Somewhat”/“A lot”/“A great deal” | 15 | (26) |

| “Not at all”/“A little” | 43 | (74) |

| “Overall, do you believe your schoolwork has been affected positively by your experience having lost a sister or brother to cancer?” | ||

| “Somewhat”/“A lot”/“A great deal” | 24 | (38) |

| “Not at all”/“A little” | 34 | (62) |

| “Overall, do you believe your work/career has been affected negatively by your experience having lost a sister or brother to cancer?” (n=51) | ||

| “Somewhat”/“A lot”/“A great deal” | 6 | (12) |

| “Not at all”/“A little” | 45 | (88) |

| “Overall, do you believe your work/career has been affected positively by your experience having lost a sister or brother to cancer?” (n=51) | ||

| “Somewhat”/“A lot”/“A great deal” | 23 | (45) |

| “Not at all”/“A little” | 28 | (55) |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence and factors of psychosocial outcomes beyond 10 years of bereavement and among siblings of children with cancer in the United States. We found that bereaved siblings are generally resilient: while almost all reported they were still affected by their experience, few reported ongoing negative sequelae, and some of their perceptions reflected personal growth or purpose. Although risky behaviors and psychological distress increased during the year after their brother or sister's death, most returned to baseline over time. Average psychological distress and social support scores were similar to population norms.

A subset of siblings had evidence of current psychological distress and/or low social support. These outcomes were related to experiences during and immediately after their brother or sister's cancer and death. Indeed, aspects of communication (how parents and health care professionals shared information), preparation for the sibling's death, and opportunities to say goodbye and work through grief were all associated with outcomes in our analyses, whereas the perceived impact of siblings’ cancer experience was not.

Much of the literature describing bereaved siblings of children with cancer comes from two distinct study populations. First, short-term data have come from a mixed-methods study of 99 bereaved family members, including 39 bereaved siblings, who were between 3 and 12 months bereaved[11,12,15,32,33]. These studies suggest that the majority of siblings report immediate changes in their personal world-view, vocational/educational goals, and relationships with family members and peers[11]. Most purposefully remember their sibling in daily activities[32]. In describing their experience with medical teams, siblings emphasize quality communication that includes the sibling[15].

Second, descriptions of longer-term experiences of bereaved siblings of children with cancer (e.g., those who are up to 9 years bereaved) have come from the Swedish cohort study[13,14,34]. Investigators have found that while most ultimately recover from their cancer experience without residual psychological distress[13], the vast majority have not yet worked through their grief[14]. Bereaved siblings in this cohort report adverse health outcomes including greater sleep difficulties when compared to non-bereaved siblings of children with cancer, but no greater use of illegal drugs or alcohol.[13]

Our findings underscore the above and confirm that bereaved siblings generally recover and find meaning from their cancer experience. Like other studies, we also found that age was associated with outcome. However, while our findings suggest that siblings who were older at the time of their brother or sister's diagnosis had inferior long-term social support than those who were younger, others have found that younger children were more socially vulnerable. [12]. These differences may be due to the fact that the prior study described teacher and peer perceptions of bereaved siblings in the year immediately after their brother or sister's death, whereas we described long-term self-reported outcomes. Indeed, our findings align with normal adolescent development of personal and social identities. It may be that both findings are simultaneously true: younger siblings are more likely to be seen as vulnerable in the early bereavement period, but older siblings are more likely to suffer long-term effects.

Our study has three key limitations. First, our participants represent three different cohorts of siblings whose cancer experiences date back as much as 20 years. Their experiences may not be typical of siblings in the current treatment era, or at all centers. Similarly, siblings were asked to describe experiences from approximately 10 years prior, subjecting our data to recall bias. Our findings are also limited to the subset of reachable siblings who agreed to participate. Nearly half of our initially identified cohort was unreachable by mail or phone, and those who responded may not be representative of bereaved siblings as a whole. We cannot determine if responders are more resilient or distressed than non-responders. Furthermore, responders were predominantly white women; the lack of racial and ethnic diversity of the sample may limit the application of our findings in other populations. Likewise, our sample size was relatively small. All of these limitations restrict the generalizability of our findings.

Second, we used single item questions to assess risky health behaviors, anxiety and depression over time. This design may enhance feasibility and diminish response burden for study participants; however, the cost may be more crude determinations of risk. For example, the visual digital scales we used to assess anxiety and depression have excellent negative-, but only moderate positive-predictive values.[30] As such, they are better at ruling out psychopathology than at ruling it in.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes directionality in the identified associations. We cannot conclude that experiences during the cancer experience lead to inferior outcomes. Rather, we can only generate hypotheses to be explored in future work. Likewise, our sample size limited the power of possible sub-analyses. We were unable to explore factors of current risky behaviors. Likewise, we lacked power to evaluate factors of current “high” distress and elected, instead, to describe changes in distress on a continuous scale. Future, prospective studies may focus on predictors of individual behaviors and distress.

This study has important implications for pediatricians, palliative care providers, and others involved in the care of healthy siblings who lose a brother or sister to serious illness. There appears to be a period of high vulnerability during and immediately after the illness experience (or death). Sharing information during this time may be challenging for parents. Most endeavor to protect their children[35], which may imply shielding the patient or sibling from difficult information. Doing so, however, may ultimately hamper bereavement processes[17]. Instead, parents should be encouraged to share as much information as possible in a developmentally target manner. Siblings may benefit from being prepared for the death of their brother or sister and having an opportunity to say “goodbye.” Other interventions may include explicit sibling-directed communication and psychosocial support during and, importantly, following the child's death.

In this study of bereaved siblings, we show that elements of the cancer experience including communication and preparation for death are associated with inferior outcomes. Future research should prospectively evaluate sibling perspectives, experiences, and outcomes. Indeed, bereaved siblings have reported they, too, believe more research is warranted[34]. In the mean-time, concurrent supportive care directed at the siblings may help promote resilience and mitigate distress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are intensely grateful to Diana Calla, beloved sister to Steven Calla, for her assistance in adapting this survey and to all of the bereaved siblings who generously participated in this study. ARR is supported by a St. Baldrick's Fellow Award.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None of the authors have financial relationships or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial needs. 2007 05/20/2011 < http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2007>. Accessed 05/20/2011.

- 2.Patterson JM, Holm KE, Gurney JG. The impact of childhood cancer on the family: a qualitative analysis of strains, resources, and coping behaviors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(6):390–407. doi: 10.1002/pon.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazak AE, Alderfer M, Rourke MT, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(3):211–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson KE, Gerhardt CA, Vannatta K, et al. Parent and family factors associated with child adjustment to pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(4):400–410. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barakat LP, Kazak AE, Meadows AT, et al. Families surviving childhood cancer: a comparison of posttraumatic stress symptoms with families of healthy children. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22(6):843–859. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala KL, et al. Promoting resilience among parents and caregivers of children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(6):645–652. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg AR, Dussel V, Kang T, et al. Psychological Distress in Parents of Children With Advanced Cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;1-7 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(8):789–805. doi: 10.1002/pon.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg AR, Baker KS, Syrjala K, et al. Systematic review of psychosocial morbidities among bereaved parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(4):503–512. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins KL, Woodgate RL. A review of qualitative research on the childhood cancer experience from the perspective of siblings: a need to give them a voice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(6):305–319. doi: 10.1177/1043454205278035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster TL, Gilmer MJ, Vannatta K, et al. Changes in siblings after the death of a child from cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(5):347–354. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182365646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerhardt CA, Fairclough DL, Grossenbacher JC, et al. Peer relationships of bereaved siblings and comparison classmates after a child's death from cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(2):209–219. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eilegard A, Steineck G, Nyberg T, et al. Psychological health in siblings who lost a brother or sister to cancer 2 to 9 years earlier. Psychooncology. 2013;22(3):683–691. doi: 10.1002/pon.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sveen J, Eilegard A, Steineck G, et al. They still grieve-a nationwide follow-up of young adults 2-9 years after losing a sibling to cancer. Psychooncology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pon.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steele AC, Kaal J, Thompson AL, et al. Bereaved parents and siblings offer advice to health care providers and researchers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(4):253–259. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31828afe05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nolbris M, Hellstrom AL. Siblings' needs and issues when a brother or sister dies of cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(4):227–233. doi: 10.1177/1043454205274722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovanola J. Sibling involvement at the end of life. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22(4):222–226. doi: 10.1177/1043454205276956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack JW, Joffe S, Hilden JM, et al. Parents' views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4759–4764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dussel V, Kreicbergs U, Hilden JM, et al. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child's location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dussel V, Bona K, Heath JA, et al. Unmeasured costs of a child's death: perceived financial burden, work disruptions, and economic coping strategies used by American and Australian families who lost children to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(8):1007–1013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards KE, Neville BA, Cook EF, Jr., et al. Understanding of prognosis and goals of care among couples whose child died of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1310–1315. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Anxiety and depression in parents 4-9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: a population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1431–1441. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9162–9171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlton R. Research: is an ‘ideal’ questionnaire possible? Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54(6):356–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onelov E, Steineck G, Nyberg U, et al. Measuring anxiety and depression in the oncology setting using visual-digital scales. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(6):810–816. doi: 10.1080/02841860601156124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foster TL, Gilmer MJ, Davies B, et al. Comparison of continuing bonds reported by parents and siblings after a child's death from cancer. Death Stud. 2011;35(5):420–440. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.553308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster TL, Gilmer MJ, Davies B, et al. Bereaved Parents' and Siblings' Reports of Legacies Created by Children With Cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2009;26(6):369–376. doi: 10.1177/1043454209340322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eilegard A, Steineck G, Nyberg T, et al. Bereaved siblings' perception of participating in research--a nationwide study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(2):411–416. doi: 10.1002/pon.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5979–5985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]