Abstract

South Africa has among the highest rates of forced sex worldwide, and alcohol use has consistently been associated with risk of forced sex in South Africa. However, methodological challenges impact the accuracy of forced sex measurements. This study explored the assessment of forced sex among South African women attending alcohol-serving venues and identified factors associated with reporting recent forced sex. Women (n=785) were recruited from 12 alcohol-serving venues in a peri-urban township in Cape Town. Brief self-administered surveys included questions about lifetime and recent experiences of forced sex. Surveys included a single question about forced sex and detailed questions about sex by physical force, threats, verbal persuasion, trickery, and spiked drinks. We first compared the single question about forced sex to a composite variable of forced sex as unwanted sex by physical force, threats or spiked drinks. We then examined potential predictors of recent forced sex (demographics, drinking behavior, relationship to the venue, abuse experiences). The single question about forced sex had low sensitivity (0.38); over half of the respondents who reported on the detailed questions that they had experienced forced sex by physical force, threats or spiked drinks reported on the single question item that they had not experienced forced sex. Using our composite variable, 18.6% of women reported lifetime and 10.8% reported recent experiences of forced sex. In our adjusted logistic regression model, recent forced sex using the composite variable was significantly associated with hazardous drinking (OR=1.92), living farther from the venue (OR=1.81), recent intimate partner violence (OR=2.53), and a history of childhood sexual abuse (OR=4.35). The findings support the need for additional work to refine the assessment of forced sex. Efforts to prevent forced sex should target alcohol-serving venues, where norms and behaviors may present particular risks for women who frequent these settings.

Introduction

South Africa reportedly has among the highest rates of forced sex worldwide (Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002). Estimates of forced sex prevalence among South African women range from 3–30%, depending on the setting, scope of the study, and data collection methods used (Gass, Stein, Williams, & Seedat, 2011; Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002; Jewkes et al., 2006). This wide range is in part attributable to the methodological challenges of measuring self-reported experiences of forced sex (Cook, Gidycz, Koss, & Murphy, 2011; Stanton, 1993). Women in South Africa who consume alcohol at high rates, and particularly those who attend alcohol-serving venues in their communities, may be particularly vulnerable to forced sex experiences. Their heightened vulnerability is in part due to the cognitive and behavioral impacts of alcohol (Boles & Miotto, 2003; Bushman & Cooper, 1990; Graham, Bernards, Wilsnack, & Gmel, 2011; Leonard, 2001; Strebel et al., 2006), as well as risks associated with the venue context (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, Kalichman, et al., 2012; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012; Weir et al., 2003; Wojcicki, 2002). Developing effective community- and individual-level interventions to respond to forced sex requires both being able to capture its prevalence, especially in high-risk settings such as alcohol-serving venues, and also to identify modifiable factors that could decrease women’s vulnerability to forced sex experiences.

Several methodological challenges impact the accuracy of forced sex measurement and resulting estimates, particularly in resource-limited settings. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines “forced sex” as an act of unwanted sex against a person’s consent, compelled by physical force or threats of force (Cook et al., 2011; Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002; WHO, 2005). The South African Police Service further defines forced sex to include vaginal, oral, and/or anal penetration of a sexual nature by whatever means and without consent (S.A.P.S., 2011; Stanton, 1993). However, individuals do not always interpret the term “forced sex” in the same way as one another, or in accordance with standard definitions (Kahn, Jackson, Kully, Badger, & Halvorsen, 2003; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004; Wood, Lambert, & Jewkes, 2007). Women may differ in considering sex to be “forced” depending on the nature of the act or the relationship with the perpetrator (Kahn et al., 2003; Mugweni, Pearson, & Omar, 2012; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004). For example, women who are forced to have sex by their intimate partner are less likely to label this as forced sex, and therefore forced sex within intimate partner relationships is under-reported and harder to quantify than forced sex outside of these relationships (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002; Jewkes, Levin, & Penn-Kekana, 2002). Women’s subjective definition of forced sex not only impacts their likelihood to seek police and medical services after a forced sexual experience (Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002), but it also impacts their responses to questions about experiences of forced sex on surveys. Data from multiple settings suggest that forced sex is consistently under-reported, which is likely attributable in part to individual perceptions about forced sex experiences and to the nature of the question or questions asked about forced sex (Cook et al., 2011; Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002; Koss, 1992).

Although perceptions of forced sex vary among women, it is still reported at high rates in South Africa. The most recently available data from the South African Demographic and Household Survey reported that 7% of sexually active women reported having ever experienced forced sex (South African Department of Health, Medical Research Council, & Macro, 2007). However, cohort studies conducted in South Africa have reported rates of forced sex as high as 30% (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2006; Jewkes et al., 2008), and studies among men suggest that over a third of South African men report perpetrating forced sex (Jewkes, Sikweyiya, Morrell, & Dunkle, 2011). The high rates of forced sex among South African women may be explained in part by contextual risk factors, including low educational attainment (Gass et al., 2011), gender-based norms about sexual violence and relationship dynamics (Kalichman et al., 2005; Shannon et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2007; Wood, Lambert, & Jewkes, 2008), and unequal gender power dynamics (Ackermann & de, 2002; Jewkes, Vundule, Maforah, & Jordaan, 2001). This gender inequality also contributes to other forms of gender-based violence in South Africa (Jewkes, 2002), such as childhood sexual abuse and intimate partner violence, and may cause a cycle of abuse that results in the revictimization of women through forced sex (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005).

Alcohol use has been shown to increase women’s risk of forced sex victimization in multiple settings, including South Africa (Chersich & Rees, 2010; Foran & O’Leary, 2008; Gass et al., 2011; Testa & Livingston, 2009; Tsai et al., 2011). While only 16% of South African women nationwide report that they drink alcohol, those who drink often do so at hazardous levels (South African Department of Health et al., 2007). Alcohol use makes women more vulnerable to experiencing sexual violence from partners and non-partners (Jewkes, 2002; Kalichman & Simbayi, 2004), because it may reduce women’s inhibitions, affect judgment, and place them in socially vulnerable situations (Abbey, Ross, McDuffie, & McDuffie, 1994; Jewkes, 2002). Men who drink heavily are more likely to perpetrate violence against women and to cause bodily harm as a result (White & Chen 2002; Graham et al. 2011; Kyriacou et al., 1999; Testa, Quigley, & Leonard, 2003). Despite alcohol being a significant risk factor for forced sex, women who experience forced sex while intoxicated are less likely to report the incident to local authorities than those who experience forced sex while sober (Felson & Pare, 2005).

The established association between alcohol use and forced sex victimization and perpetration suggests that alcohol serving venues are sites where women may be particularly vulnerable to forced sex (Demers et al. 2002; Freisthler, 2011; Harfrod et al 2002; Van de Good et al. 1990). South African drinking venues have a predominately male patronage, and therefore tend to be places that exacerbate cultural norms around male dominance (Cunradi, 2010). Violence against women in South Africa, including forced sex, may be viewed by some as normative behavior, and venue owners may tolerate or even promote these norms in the venues (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012). In addition, qualitative studies have documented norms and patterns around alcohol consumption whereby men purchase alcohol for women, and in turn feel a sense of sexual entitlement that could lead to forced sex (Jewkes, Fulu, Roselli, & Garcia-Moreno, 2013; Jewkes et al., 2011; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, Kalichman, et al., 2012; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012). Women may face further risks for forced sex when they leave the bars to walk home, particularly if they are intoxicated (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, Kalichman, et al., 2012; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012). Given the heightened and particular risk for forced sex that is embedded in drinking establishments, there is a need to situate research on forced sex experiences among women in alcohol serving venues, in an effort to identify prevention strategies in these settings.

The goal of this study was to examine experiences of forced sex among a sample of female patrons of alcohol-serving venues in Cape Town, South Africa, with two specific aims. First, we examined issues of measurement by describing differences in endorsing a single question about forced sex compared to endorsing more specific questions about forced sex experiences. Second, we examined factors associated with recent forced sex in this sample.

Methods

Setting

The data presented here are part of a community-based longitudinal study of HIV risk in the context of alcohol-serving establishments in a single township in Cape Town, South Africa. Alcohol-serving venues in the community were identified through street intercept surveys using the PLACE methodology (Weir et al., 2003). A total of 124 venues were first identified and visited to assess eligibility (space for patrons to sit and drink in the venue, >50 unique patrons per week, >10% female patrons, and willing to have the research team visit the venue on a regular basis). The final twelve venues were selected to have geographic diversity, a mix of large and small sites, and an equal number of venues with predominantly Black African or Coloured (an ethnic group unique to the South African setting) patrons.

Procedures

Data were collected by six study staff, all South Africans (four women and two men) who had university education and/or several years of prior research experience. They received extensive training and oversight by the local principal investigator (DS) and the study coordinator (DP). The staff were matched by race and language to the venues. In each venue, they first conducted one week of observation, in order to understand the setting and establish rapport, and then conducted one week of cross-sectional surveys among venue patrons. During the data collection period, patrons were approached immediately upon entering the venues. The study staff assessed patrons’ sobriety using informal questioning and observation, and patrons were only asked to complete the survey if the researchers felt confident that they were not intoxicated. After providing oral consent, participants were given the option of completing the survey in Xhosa, Afrikaans, or English, either as a self-administered written survey or as a staff-administered survey. Almost all participants (96.9%) chose to complete the survey themselves and of the 3.1% that were staff-administered, only seven cases were administered by a male staff. Researchers ensured that participants had privacy to complete the survey, and then had the participants place their survey inside an envelope with other surveys, in order to emphasize the anonymity of the data. The survey included 106 questions and took on average 10–15 minutes to complete. Study participants received a cup with the study logo in appreciation for completing the survey. All study procedures were approved by the ethical review boards of Stellenbosch University, University of Connecticut and Duke University.

Measures

Forced sex

Experience of forced sex was measured first with a single question about lifetime experience of forced sex and a single question about recent experience of forced sex, and second with a series of detailed questions about forced sex experience (both lifetime and recent). The single lifetime question was phrased: “Has someone ever forced you to have sex when you didn’t want to?” and the single recent question was phrased: “In the last 4 months, has someone forced you to have sex when you didn’t want to?” The phrasing of these questions were adapted from the Demographic and Health Survey (USAID, 2011). Notably, no definition of force is provided in the question, so the respondent is free to interpret “force” as she wishes (e.g., physical force, emotional force, or anything else that the respondent considers as force). Response options were yes and no.

The detailed questions about forced sex were intended to provide greater definition to the term “forced”. They were informed by our team’s prior qualitative work (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, Kalichman, et al., 2012; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012) that explored this population’s sexual experiences, including forced sex. The five detailed lifetime questions asked were: “Has anyone ever done the following to make you have sex when you didn’t want to: 1) used physical force? 2) used threats? 3) talked you into it? 4) used trickery or manipulation? 5) spiked your alcohol/drink?” The same questions were repeated for the period “in the past 4 months.” Response options for each question were yes and no.

Based on the responses to the detailed questions, we created a composite variable for forced sex (lifetime and recent), with women who endorsed that they had been made to have sex using physical force, threats, or spiked drink classified as experiencing forced sex (αlifetime=0.68, and αrecent=0.72). This composite variable was based on the most common definitions of forced sex (Krug et al., 2002; WHO, 2005), and was meant to exclude some of the more nuanced experiences of trickery or manipulation that happen in the absence of physical force, threats or spiked drinks.

Predictor variables

Demographics included questions about the participant’s age, self-identified race (Black African, Coloured, or Other), highest level of education completed, relationship status, and socio-economic status (employment and whether the home had water and electricity).

Alcohol use was assessed with the AUDIT-c, the first three questions from the full Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Participants reported their frequency of drinking alcohol (1= “never” to 5 = “more than four times per week”), quantity of drinks consumed on a typical day (1 = “none” to 5 = “10 or more”), and frequency of binge drinking (1 = “never” to 5 = “daily or almost daily”) (α=0.79). Participants who drank 3 or more drinks per occasion or reported binge drinking (6 or more drinks in one sitting) on at least a weekly basis were classified as hazardous drinkers.

Recent intimate partner violence (IPV) was assessed by asking whether “a sex partner hit you” in the past four months. Response options were yes and no.

History of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was assessed with a single question: “As a child, were you ever sexually abused (that is, forced to have some kind of sexual contact, like touching, oral sex or intercourse)?” Response options were yes and no.

Distance to venue was assessed with a single question: “How long does it take you to walk from your home to this bar?” Response options ranged from 1=“less than 15 minutes” to 4=“more than one hour”. This variable was included based on our previous findings that living farther from the venue conferred risk in sexual behavior (Eaton et al., 2013) and gender-based violence (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012).

Frequency of attending the venue was assessed with a single question: “About how often do you come to this bar?” Responses options ranged from 1=“this is my first time” to 5=“almost daily”.

Analysis

The completed surveys were scanned into a database using Remark Office OMR Version 6 (Gravic, Inc, Malvern, PA), and manual checks were performed to identify errors. SPSS Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. For the purposes of this analysis, only data from the female participants (n=785) were included. To address our first aim, we first examined the prevalence of both recent and lifetime experiences of forced sex, considering both the single questions and the detailed questions about forced sex. We then examined the extent to which the single question of recent forced sex correctly classified respondents, compared to our composite variable (endorsing forced sex by physical force, threats, or spiked drink). For purposes of analysis, the single question was considered the “screener” and compared to the “gold standard” of the composite variable. We calculated sensitivity (the proportion of actual positives that are correctly classified) and specificity (the proportion of actual negatives that are correctly classified) for the single question. We also calculated the positive predictive value (ratio of true positives to combined true and false positives) and negative predictive value (ratio of true negatives to combined true and false negatives) of the single question, compared with the composite variable.

To address our second aim, we examined factors associated with recent forced sex in this sample, using logistic regression to predict our composite measure of recent forced sex. Demographic characteristics (age, race, education, marital status, and employment) and factors that were associated with the outcome in the unadjusted model at p<.10 were included in the adjusted model.

Results

Description of the sample

As shown in Table 1, the female patrons were 18–90 years old (M = 32.2, SD = 11.4), predominantly Black (41.6%) or Coloured (56.1%), and mostly (74.7%) unmarried. More than two-thirds had not completed secondary school (68.1%) and nearly three quarters were unemployed (74.1%). The majority of the participants (67.9%) met our criteria for hazardous drinking. Most (77.9%) lived within walking distance of the venue, and nearly half (46.9%) attended the venue at least weekly. Almost a fifth of the sample (17.9%) reported experiencing intimate partner violence in the previous four months, and a tenth (9.9%) reported having a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Table 1.

Description of the sample (n=785)

| Age | ||

| Mean(SD) | 32.2 (11.4) | |

| Range | 18–90 | |

| n | % | |

| Race | ||

| Black African | 327 | 41.6% |

| Coloured | 440 | 56.1% |

| Other | 18 | 2.3% |

| Education | ||

| Grade 7 or less | 155 | 19.8% |

| Grade 8–11 | 378 | 48.3% |

| Completed secondary | 194 | 24.8% |

| Post-secondary | 55 | 7.0% |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 197 | 25.3% |

| Unmarried | 582 | 74.7% |

| SES indicators | ||

| Unemployed | 577 | 74.1% |

| Lives in a house without electricity/water | 123 | 15.7% |

| Relationship to the drinking venue | ||

| Lives within 15 min walk from venue | 607 | 77.9% |

| Visits venue on at least a weekly basis | 366 | 46.9% |

| Hazardous drinking | 532 | 67.9% |

| Recent physical intimate partner violence | 140 | 17.9% |

| History of childhood sexual abuse | 77 | 9.9% |

Measurement of forced sex

The first aim of the study was to examine the assessment of forced sex. When responding to the single question regarding forced sex, 18.9% of the participants reported experiencing forced sex in their lifetime and 9.0% reported forced sex within the last four months (Table 2). Based on detailed questions about the types of forced sex, 153 women (19.5%) endorsed at least one of the recent forced sex items, and 223 (28.4%) endorsed at least one of the lifetime forced sex items. Using our composite variable of forced sex (any occasion of forced sex by physical force, threats, or spiked drinks), 10.8% reported recent forced sex and 18.6% reported lifetime forced sex.

Table 2.

Reports of forced sex by various questions (n=785)

| 4 months | Lifetime | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Single question: “Has someone forced you to have sex when you didn’t want to?” | 71 | 9.0% | 148 | 18.9% |

| Specific questions on forced sex by: | ||||

| Physical force | 57 | 7.3% | 92 | 11.7% |

| Threats | 59 | 7.5% | 105 | 13.4% |

| Talked into it | 107 | 13.6% | 151 | 19.2% |

| Trickery/manipulation | 68 | 8.7% | 103 | 13.1% |

| Spiked drinks | 44 | 5.6% | 57 | 7.3% |

| New definition: Forced sex by physical force, threats or spiked drinks | 85 | 10.8% | 146 | 18.6% |

Each detailed recent forced sex question significantly and positively correlated with the single item measure (Table 3). “Physical force” had the strongest positive correlation with the single item (r = 0.36, p < .001), while “talked into it” had the weakest positive correlation with the single item (r = 0.24, p < .001). In addition, the detailed questions were significantly correlated to each other, with correlation values ranging from 0.38–0.67 (p<.001). Our composite variable of forced sex was significantly correlated with the single item (r = 0.33, p < .001).

Table 3.

Correlations among recent forced sex measures (n=776)

| Single item | Physical force | Threats | Talked into it | Trickery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single item | - | ||||

| Physical force | 0.364 | - | |||

| Threats | 0.256 | 0.666 | - | ||

| Talked into it | 0.244 | 0.443 | 0.452 | - | |

| Trickery | 0.320 | 0.588 | 0.582 | 0.482 | - |

| Spiked drink | 0.308 | 0.558 | 0.574 | 0.378 | 0.481 |

Note: Correlations calculated using Phi coefficient. All correlations were significant at the level of p < .001.

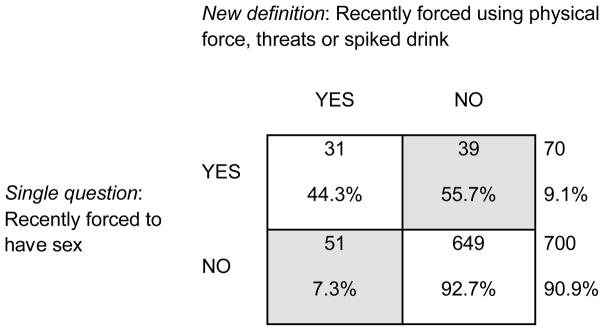

The responses on the single item were compared to the new composite measure to examine issues of measurement (Table 4). Combining the endorsement of either the single item or the composite variable, 15.9% of the participants reported that they had experienced forced sex. The single item misclassified 51 participants as not having experienced forced sex, even though they endorsed one of the detailed questions that made up the composite variable for forced sex experiences. In other words, 51 participants reported that they had recently been forced to have sex when someone used physical force, threats, or had their drink spiked; however, when asked the single question about any recent forced sex experience, they reported “no”. The sensitivity of the single item was low (0.38, 95% CI: 0.27–0.48), with a Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of 44% (95% CI: 33–56%), indicating that the single item identified less than half of the “true” positive cases of forced sex, as confirmed by the more robust composite measure. However, the specificity of the single item was high (0.94, 95% CI: 0.93–0.96), with a Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of 93% (95% CI: 91–95%), indicating that the single item identified most of the participants who reported not having experienced forced sex as confirmed by the composite measure.

Table 4.

Comparison of single question on recent forced sex with new definition of forced sex (n=770)

|

χ2= 91.6 p<.001

Sensitivity: 0.38 (95% CI 0.27 – 0.48) Specificity: 0.94 (95% CI 0.93 – 0.96)

Factors associated with forced sex

The second aim of the study was to describe the factors associated with forced sex among the female venue patrons (Table 5). In the unadjusted univariate analysis predicting forced sex, recent physical IPV, a history of childhood sexual abuse, hazardous drinking, and living >15 minutes walking distance to the venue were significantly related to forced sex experiences. In an adjusted regression model including all of the significant predictors, all of these variables remained significant with other abuse experiences being particularly strong predictors. Demographic factors were not associated with forced sex. Women were twice as likely to report forced sex if they had experienced recent physical IPV (OR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.48–4.34) and more than four times more likely to report forced sex if they had a history of childhood sexual abuse (OR = 4.35, 95% CI = 2.39–7.92). Drinking and venue characteristics were also positively associated with forced sex. Hazardous drinkers were more likely to report forced sex (OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.03–3.58), and women who lived >15 minutes walking distance from the venue were more likely to report forced sex, compared to those who lived closer (OR = 1.81, 95% CI =1.05–3.11)

Table 5.

Logistic regression model of factors associated with women’s reports of recent forced sex (using physical force, threats, or spiked drinks) (n=767)

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.97 – 1.01) | .328 | 1.00 (0.97 – 1.02) | .797 |

| Race (Ref: Coloured or Other) | 1.28 (0.81 – 2.01) | .286 | 1.09 (0.63 – 1.90) | .752 |

| Education (Ref: Did not complete secondary school) | 1.27 (0.78 – 2.05) | .327 | 0.98 (0.55 – 1.74) | .932 |

| Marital status (Ref: Not married) | 1.12 (0.65 – 1.93) | .681 | 1.06 (0.57 – 2.00) | .847 |

| Employment (Ref: Not employed) | 0.99 (0.59 – 1.67) | .964 | 0.93 (0.53 – 1.64) | .802 |

| Abuse experience | ||||

| Recent IPV | 3.89 (2.39 – 6.35) | <.001 | 2.53 (1.48 – 4.34) | <.001 |

| History of childhood sexual abuse | 6.45 (3.70 – 11.21) | <.001 | 4.35 (2.39 – 7.92) | <.001 |

| Drinking & venue | ||||

| Hazardous drinking | 2.48 (1.37 – 4.52) | .003 | 1.92 (1.03 – 3.58) | .041 |

| Walking distance to venue (Ref: <15 min) | 2.15 (1.32 – 3.51) | .002 | 1.81 (1.05 – 3.11) | .033 |

| Frequency of attending venue (Ref: Weekly or more) | 0.81 (0.51 – 1.29) | .381 | ||

Discussion

This research sought to gain insights into and refine the assessment of forced sex among South African women, and to examine factors that increase risk for forced sex among women who attend alcohol-serving venues. Consistent with other studies in South Africa (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes & Abrahams, 2002; Jewkes et al., 2006), about a fifth of all women in our sample (18.6%) reported that they had experienced forced sex in their lifetimes. The sample was fairly young, suggesting that if patterns of forced sex persist, the overall lifetime prevalence will likely be far higher as individuals age.

Our findings confirm the challenges of measuring forced sex (Kahn et al., 2003; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004; Wood et al., 2007), and point to the limitations of survey measurement, where items about forced sex may be subject to individual respondents’ interpretation. In our data, the single question about recent forced sex had low sensitivity; it missed 51 cases that were reported when women were asked more specific questions (forced sex by physical force, threats, or spiked drinks). At the same time, 39 women who reported that they had not recently experienced any of those specific forms of forced sex answered yes to the single question about forced sex. It is likely that these 39 individuals were recalling a forced sex experience that did not meet the criteria of forced sex by physical force, threats, or spiked drinks. The utility of a forced sex measure with three specific questions is that it provides a more uniform and consistent definition of what “counts” as forced sex. Nevertheless, forced sex is a nuanced concept that will continue to benefit from addressing issues related to its measurement. Qualitative work, specifically cognitive interviewing techniques, is necessary to better understand how women respond to questions about forced sex and to identify the most appropriate items to capture forced sex experiences.

This sample of women recruited from alcohol-serving venues reported high levels of drinking, with a majority of the sample reporting that they typically drank 3 or more drinks per sitting or participated in binge drinking at least weekly. Women who drank at hazardous levels had a two-fold increase of reporting recent forced sex. This finding is consistent with other studies that have linked alcohol consumption to forced sex experiences in South Africa (Chersich & Rees, 2010; Kalichman et al., 2005). In addition, women who attended venues farther from their homes had an increased risk of forced sex. There is a potential protective effect of drinking in local settings, where people know each other, and a potential risk of experiencing forced sex when traveling to/from venues that are farther from the home. Our mixed-methods work in this setting confirms that smaller, more neighborhood-focused venues may confer less risk related to sexual behavior and violence, compared with larger, less localized settings (Eaton et al., 2013; Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions to address forced sex should focus both on patterns of alcohol consumption, as well as the venue setting itself as sites of risk.

Forced sex was also more common among women who reported other abuse experiences, notably childhood sexual abuse and intimate partner violence. A large collection of studies have documented the linkage between early sexual victimization and repeated victimization as an adult (Classen et al., 2005), due in large part to mental health distress and maladaptive coping behaviors (Noll, Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003). The relationship between forced sex and recent intimate partner violence (IPV) could be a reflection of physical and sexual violence co-occurring in relationships, or of one type of abuse predisposing women to another type of abuse. Our findings suggest that organizations that provide services for abused women should concurrently address physical and sexual violence, and should assess and treat exposure to childhood sexual abuse and resultant mental health and behavioral sequelae that might predispose women to forced sex experiences in adulthood. It is also important that trauma organizations assess and treat alcohol use and dependence in the context of trauma treatment.

This study provides lessons for measuring forced sex, and points to opportunities to prevent forced sex in this setting. Our findings support the need for additional work on the measurement of forced sex, in order to capture the range of forced sex experiences. Multiple questions about forced sex, each providing specificity about the nature of the forced sex experience, can control for subjective interpretation. In addition, developing a narrated introduction and considering the appropriate ordering of the questions may promote more accurate reporting (Cook et al., 2011). Future measures of forced sex should also collect information on the woman’s relationship with the perpetrator and the context of the abuse experience. Information about the perpetrator (e.g., whether the perpetrator was previously known to the victim, whether the perpetrator was an intimate partner, whether the perpetrator frequents the study venue) and the context of the abuse (e.g., one-time repeated abuse experiences, the role of substance use) would help to interpret the findings. Quantification of forced sex experiences should ideally be complemented with qualitative exploration to understand the various types of forced sex experiences in the setting and to identify the most salient entry points for intervention.

The data presented here also has implications for efforts to prevent forced sex in South Africa. Importantly, these efforts should target alcohol-serving venues, where norms and behaviors may present risks for women who frequent these settings. Reducing risky drinking patterns by directly addressing women’s alcohol dependence, confronting the behavioral and psychological sequelae of abuse histories, and increasing community policing in and around alcohol-serving venues may be particularly meaningful and impact interventions. Increasingly, greater attention has been directed at the need to develop male-focused interventions for these settings to change attitudes and behaviors that contribute to high rates of sexual perpetration (Jewkes et al., 2013; Kalichman et al., 2009; van den Berg et al., 2013). Although this study did not assess male attitudes and behaviors, there is evidence that pro-violence attitudes and male perpetration behaviors in South Africa are high (Jewkes et al., 2011). In alcohol-serving venues, interventions may include working with venue owners in their roles as community leaders (Watt, Aunon, Skinner, Sikkema, MacFarlane, et al., 2012) to enable them to become advocates for the prevention of forced sex, and to confront entrenched norms about masculinity and gender hierarchies through peer-led interventions.

In interpreting the findings, this paper has some limitations that must be considered. The study included a small number of alcohol-serving venues in a single South African township, and the findings may not generalize to other settings. We did not include an objective measure of intoxication, and it is therefore possible that some participants had been drinking prior to participating in the survey, which may have influenced accuracy of responses. The surveys were conducted in the venue setting, and although the study staff made every effort to ensure privacy and confidentiality, women may have been reluctant to disclose highly personal and sensitive information about forced sex while in a public social space. The presence of male research staff may have heightened this hesitation to disclose. Our items about forced sex did not include definitions of sex (e.g., vaginal, anal, oral, or other sexual acts), and they did not explicitly state that forced sex could include experiences with a spouse or partner. This lack of definition may have influenced consistency of interpretation across respondents. Additionally, the absence of event-level data makes it impossible to understand whether endorsement of the detailed questions reflected multiple forced sex experiences, or whether one event may have included multiple expressions of forced sex. Finally, this study employed a cross-sectional methodology, and inferences about causality are unwarranted.

Sexual assault against women in South Africa is a public health crisis, impacting women’s psychological and physical well-being, and harming the social fabric of families and communities. Adequately responding to this crisis requires having proper tools to quantify the prevalence of forced sex experiences. The findings shed light on the challenges of measuring forced sex, and point to the need to move away from single item measures to more detailed questions about women’s experiences. Additionally, the findings suggest that sexual assault prevention efforts would benefit from targeted interventions in alcohol-serving venues, which may be particularly risky environments for the sexual assault of women. Intervention approaches in these settings should focus on responsible consumption of alcohol, safety traveling to and from the venues, and addressing the sequelae of other abuse experiences from childhood and adulthood. Targeted programs in these high-risk environments, combined with changes at the policy and social levels, are needed to stem the tide of sexual assault in South Africa.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant R01 AA018074. We also appreciate the support and infrastructure we received from the Duke Center for AIDS Research (NIAID grant P30 AI064518). We are grateful to all the men and women who participated in this study. We would like to acknowledge the South African research team that collected the data, specifically Simphiwe Dekeda, Albert Africa, Judia Adams, Bulelwa Nyamza and Jabulile Mantantana. We thank Jessica MacFarlane and Karmel Choi for their early contributions that led towards this manuscript.

References

- Abbey A, Ross LT, McDuffie D. Alcohol’s role in sexual assault. Addictive Behaviors in Women. 1994:97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann L, de K. Social factors that make South African women vulnerable to HIV infection. Health Care for Women International. 2002;23(2):163–172. doi: 10.1080/073993302753429031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles SM, Miotto K. Substance abuse and violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8(2):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, Cooper HM. Effects of alcohol on human aggression: an integrative research review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(3):341–354. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chersich M, Rees H. Causal links between binge drinking patterns, unsafe sex and HIV in South Africa: its time to intervene. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2010;21(1):2–7. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2000.009432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen CC, Palesh OG, Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: a review of the empirical literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(2):103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SL, Gidycz CA, Koss MP, Murphy M. Emerging issues in the measurement of rape victimization. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(2):201–218. doi: 10.1177/1077801210397741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB. Neighborhoods, alcohol outlets and intimate partner violence: addressing research gaps in explanatory mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7(3):799–813. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7030799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Pitpitan EV, Cain DN, Watt MH, Sikkema KJ, Skinner D, Pieterse D. The relationship between attending alcohol serving venues nearby versus distant to one’s residence and sexual risk taking in a South African township. J Behav Med. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(14):2764–2789. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Wilsnack SC, Gmel G. Alcohol may not cause partner violence but it seems to make it worse: a cross national comparison of the relationship between alcohol and severity of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(8):1503–1523. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(7):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Koss MP, Levin JB, Nduna M, Jama N, Sikweyiya Y. Rape perpetration by young, rural South African men: Prevalence, patterns and risk factors. Social science & medicine. 2006;63(11):2949–2961. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Fulu E, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C. Prevalence of and factors associated with non-partner rape perpetration: findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. The Lancet Global Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70069-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(9):1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A, Duvvury N. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, Dunkle K. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e29590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52(5):733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, Halvorsen J. Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27(3):233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Clayford M, Arnolds W, Mxoli M, Smith G, Cherry C, Shefer T, Crawford M, Kalichman MO. Integrated gender-based violence and HIV Risk reduction intervention for South African men: results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10(3):260–269. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Cherry C, Jooste S, Mathiti V. Gender Attitudes, Sexual Violence, and HIV/AIDS Risks among Men and Women in Cape Town, South Africa. The Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(4):299–305. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. The under detection of rape: Methodological choices influence incidence estimates. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48(1):61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. The lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. Domestic violence and alcohol: what is known and what do we need to know to encourage environmental interventions? Journal of Substance Use. 2001;6(4):235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mugweni E, Pearson S, Omar M. Traditional gender roles, forced sex and HIV in Zimbabwean marriages. Culture, health & sexuality. 2012;14(5):577–590. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.671962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Horowitz LA, Bonanno GA, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Revictimization and self-harm in females who experienced childhood sexual abuse: results from a prospective study. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18(12):1452–1471. doi: 10.1177/0886260503258035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, Muehlenhard CL. Was it rape? The function of women’s rape myth acceptance and definitions of sex in labeling their own experiences. Sex Roles. 2004;51(3–4):129–144. [Google Scholar]

- SAPS. Crime Report 2010/2011. South African Police Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Leiter K, Phaladze N, Hlanze Z, Tsai AC, Heisler M, Iacopino V, Weiser SD. Gender Inequity Norms Are Associated with Increased Male-Perpetrated Rape and Sexual Risks for HIV Infection in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e28739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South African Department of Health, Medical Research Council, & Macro, O. South African Demographic and Health Survey. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Department of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton S. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of empirical data on violence against women in greater Cape Town from 1989 to 1991. University of Cape Town: Institute of Criminology; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Strebel A, Crawford M, Shefer T, Cloete A, Henda N, Kaufman M, Simbayi L, Magome K, Kalichman S. Social constructions of gender roles, gender-based violence and HIV/AIDS in two communities of the Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance (SAHARA) 2006;3(3):516–528. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2006.9724879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA. Alcohol consumption and women’s vulnerability to sexual victimization: can reducing women’s drinking prevent rape? Substance Use and Misuse. 2009;44(9–10):1349–1376. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Leiter K, Heisler M, Iacopino V, Wolfe W, Shannon K, Phaladze N, Hlanze Z, Weiser SD. Prevalence and Correlates of Forced Sex Perpetration and Victimization in Botswana and Swaziland. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1068–1074. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USAID. Domestic Violence Module: Questionnaire, Interviewer’s Manual, and Tabulation Plan. Demographic and Health Surveys Toolkit 2011 [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg W, Hendricks L, Hatcher A, Peacock D, Godana P, Dworkin S. ‘One Man Can’: shifts in fatherhood beliefs and parenting practices following a gender-transformative programme in Eastern Cape, South Africa. Gend Dev. 2013;21(1):111–125. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2013.769775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Aunon FM, Skinner D, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC, Pieterse D. Because he has bought for her, he wants to sleep with her”: Alcohol as a currency for sexual exchange in South African drinking venues. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(7):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Aunon FM, Skinner D, Sikkema KJ, MacFarlane JC, Pieterse D, Kalichman SC. Alcohol-serving venues in South Africa as sites of risk and potential protection for violence against women. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47(12):1271–1280. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.695419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. From people to places: focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17(6):895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Addressing violence against women and achieving the Millennium Development Goals 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Wojcicki JM. “She drank his money”: survival sex and the problem of violence in taverns in Gauteng province, South Africa. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2002;16(3):267–293. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K, Lambert H, Jewkes R. “Showing roughness in a beautiful way”: talk about love, coercion, and rape in South African youth sexual culture. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2007;21(3):277–300. doi: 10.1525/maq.2007.21.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood K, Lambert H, Jewkes R. “Injuries are beyond love”: physical violence in young South Africans’ sexual relationships. Medical Anthropology. 2008;27(1):43–69. doi: 10.1080/01459740701831427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]