Abstract

Background - Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM) is a promising new breast imaging modality that is superior to conventional mammography for breast cancer detection. We aimed to evaluate correlation and agreement of tumor size measurements using CESM. As additional analysis, we evaluated whether measurements using an additional breast MRI exam would yield more accurate results.

Methods - Between January 1st 2013 and April 1st 2014, 87 consecutive breast cancer cases that underwent CESM were collected and data on maximum tumor size measurements were gathered. In 57 cases, tumor size measurements were also available for breast MRI. Histopathological results of the surgical specimen served as gold standard in all cases.

Results - The Pearson's correlation coefficients (PCC) of CESM versus histopathology and breast MRI versus histopathology were all >0.9, p<0.0001. For the agreement between measurements, the mean difference between CESM and histopathology was 0.03 mm. The mean difference between breast MRI and histopathology was 2.12 mm. Using a 2x2 contingency table to assess the frequency distribution of a relevant size discrepancy of >1 cm between the two imaging modalities and histopathological results, we did not observe any advantage of performing an additional breast MRI after CESM in any of the cases.

Conclusion - Quality of tumor size measurement using CESM is good and matches the quality of these measurement assessed by breast MRI. Additional measurements using breast MRI did not improve the quality of tumor size measurements.

Keywords: breast cancer, mammography, CESM, CEDM, MRI.

Introduction

Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography (CESM, or contrast-enhanced dual-energy mammography: CEDM) is a promising new breast imaging modality. In CESM, an iodine-based contrast agent is intravenously administered two minutes prior to the acquisition of the mammographic images. These consist of a dual-energy technique which results in the acquisition of both a low- and high-energy image 1. The low-energy image is similar to full-field digital mammography (FFDM) 2, whereas the high-energy image is used to generate a so-called 'recombined image', in which information on enhancing structures can be appreciated. A summary review of the most recent publications showed that the diagnostic accuracy of CESM in breast cancer detection was consistently superior to FFDM 3.

Breast MRI is currently regarded as the most accurate breast imaging modality available. Breast MRI is superior to all other imaging modalities for preoperative evaluation of breast cancer extent, since it assesses tumor diameter most accurately 4-6. However, since breast MRI and CESM are based on similar principles, CESM might show a similar performance. Previously, only one study reported on the quality of tumor diameter measurements using both CESM and breast MRI 7. In this paper the correlation of both measurements (with histopathological analysis as the gold standard) was presented. Studying the reproducibility of these results and more importantly the agreement between these two measurements provides additional information on the quality of these measurements 8.

In this study, our aims were two-fold: (1) to evaluate correlation and agreement of tumor size measurements using CESM, and (2) to evaluate whether measurements using an additional breast MRI exam would yield more accurate results.

Materials and Methods

In the Netherlands, research covered by the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act must be submitted to an accredited medical ethics committee for approval. Our medical ethics committee concluded that the research proposal of the current retrospective study does not, under Dutch law, require medical ethics approval because no extra burden is placed on research subjects. Therefore, the need for obtaining written informed consent was waived by Maastricht University Medical Center ethics committee (decision number: METC 14-4-071).

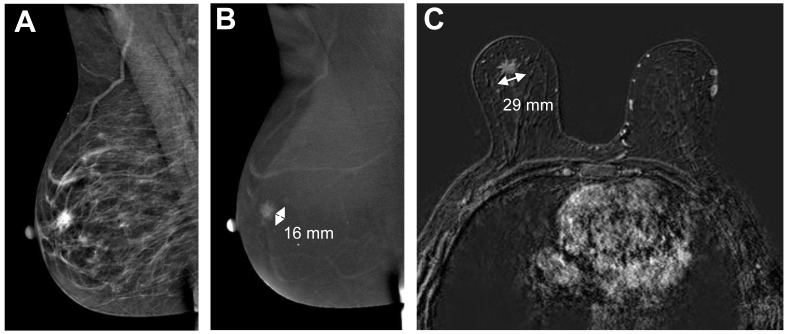

In our hospital, all women recalled from the breast cancer screening program who have no contra-indications for the intravenous administration of an iodine-based contrast agent are eligible for CESM (SenoBright*, GE Healthcare, United Kingdom). The CESM imaging protocol has been described elsewhere in detail 9. In short, a non-ionic monomeric low-osmolar contrast agent (iopromide; Ultravist® 300, Bayer Healthcare, Germany) is administered intravenously, after which CESM acquires a set of low and high energy images in quick succession. As a result, an image similar to a conventional mammogram (i.e. the low-energy CESM image) 2 and an image containing information on enhancement of structures can be reviewed (i.e. the recombined CESM image) (Figure 1).

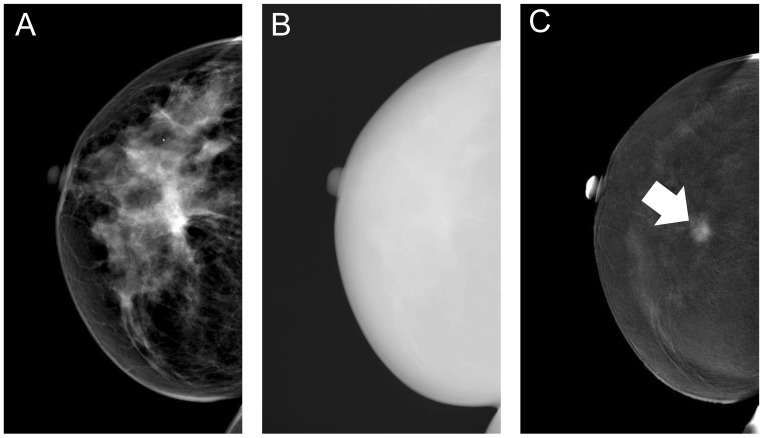

Figure 1.

Typical example of the different contrast-enhanced spectral mammography images. First, a low-energy image is acquired (A), immediately followed by the high-energy image (B), which is used in post-processing to create the recombined image (C), in which the invasive breast cancer is clearly visible (arrow).

All CESM exams performed between January 1st 2013 and April 1st 2014 were included in this retrospective study. Out of this database, all consecutive breast cancer cases were collected, including ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Since both low energy and recombined images are an integral part of the exam, maximum tumor diameter measurement is performed on the entire CESM exam (i.e. viewing both the low and recombined images together in both projection views) using calipers and a dedicated mammography workstation (IDI MammoWorkstation, GE Healthcare, United Kingdom). Core biopsies were performed immediately after the CESM exam.

In some cases, breast MRI was performed for preoperative staging, according to our national guidelines 10. These indications for preoperative breast MRI were: women considering breast conserving therapy with either invasive lobular carcinoma, high grade ductal carcinoma in situ or size discrepancies between mammography and ultrasound >1 cm, and young women with dense breast tissue. All breast MRI exams were performed on a single 1.5 Tesla scanner (Intera, Philips Healthcare, the Netherlands) using a dedicated 16-channel breast coil. The protocol consisted of a transverse T2w sequence and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), combined with a dynamic, contrast-enhanced T1w sequence in the transverse plane (consisting of 1.0 mm isotropic voxels and a temporal resolution of 93 seconds). Blinded for CESM measurements, tumor diameter measurements were performed on the first dynamic scan after contrast administration, i.e. at peak enhancement of the tumor, using calipers and a dedicated workstation (Dynacad, Invivo International, the Netherlands). We recorded the presence of hematomas or other post-biopsy effects seen on breast MRI which might influence the accuracy of tumor size measurements.

After surgery, specimens were received fresh, routinely handled at the pathology department, and tumor size was macroscopically measured in three dimensions. Histopathological examination was performed after formalin fixation and paraffin embedding. Hematoxillin and eosin stained sections were examined to assess tumor size. Microscopic carcinoma size was correlated with tumor size on gross examination. Tumor diameter (in mm) was defined as largest tumor size based on macroscopic and histopathologic examination. For the comparison of maximum lesion diameter found using CESM and pathology, surrounding DCIS was included in the final maximum diameter measurement. In case of multifocal breast cancer, the maximum diameter of the largest invasive tumor (i.e. the primary index tumor) was assessed.

Statistical analysis

The correlation between maximum tumor diameter based on CESM and histopathology, and breast MRI and histopathology was expressed using scatterplots and Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC). In addition, the agreement between these measurements was expressed using Bland-Altman plots and calculating the mean difference in diameter between these measurements, including their 95% limits of agreement (LOA) 11.

A relevant size discrepancy was defined as a size difference of >1 cm between CESM measurements and histopathological results, in line with previous publications 12, 13 and concordant with margins used by our surgeons. A 2x2 contingency table was created for both imaging modalities and their corresponding size estimations. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). All p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

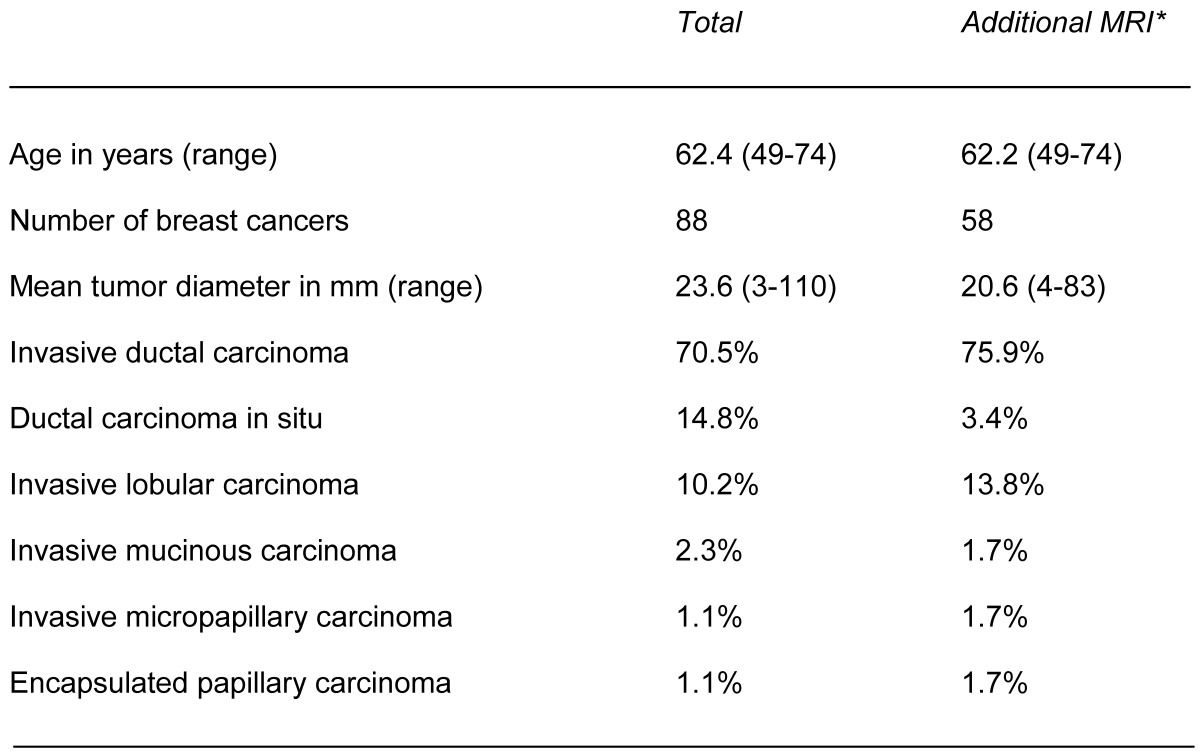

In the study period, a total of 325 patients were referred to our hospital because of a suspicious abnormality detected in the breast cancer screening program. Of these, 87 (26.8%) women were diagnosed with either an invasive breast cancer or DCIS, which is concordant with disease prevalence known from previous publications for this population 14. Mean age (of all patients) was 62.4 years, range 49-74 years. One patient had bilateral breast cancer, resulting in a total of 88 breast cancer lesions for the final analysis. For the additional analyses using breast MRI related data, 57 cases (58 lesions) were available (i.e. having both CESM and breast MRI exams performed within two weeks' time frame). Invasive ductal carcinoma was the most frequently observed cancer type (70.5%), followed by DCIS (14.8%) and invasive lobular carcinoma (10.2%). Mean tumor diameter was 23.6 mm, range 3 to 110 mm. We did not observe any post-biopsy effects on breast MR images that interfered with the accuracy of tumor size measurements. Table 1 presents detailed patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Patient characteristics for the total population and the cases that underwent both CESM and breast MRI (*).

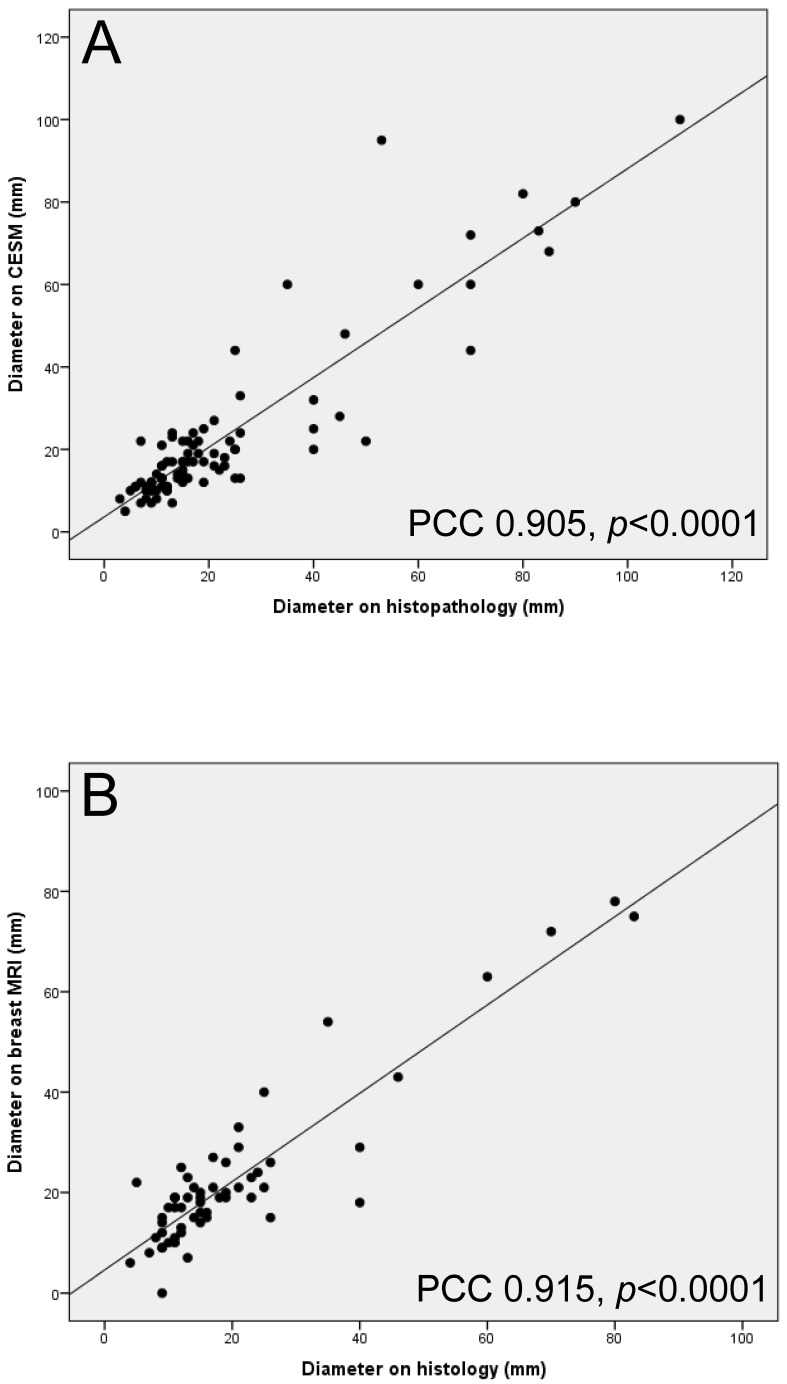

The correlations of maximum tumor diameter measurements between CESM and histopathology, and breast MRI and histopathology are presented in Figure 2. The PCC of CESM and histopathology was 0.905, p<0.0001. The PCC for the comparison between breast MRI and histopathology was slightly higher than the one for CESM: 0.915, p<0.0001.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots and Pearson's correlation coefficients (PCC) of maximum tumor diameter measurements between CESM and histopathology (A) and (B) breast MRI and histopathology.

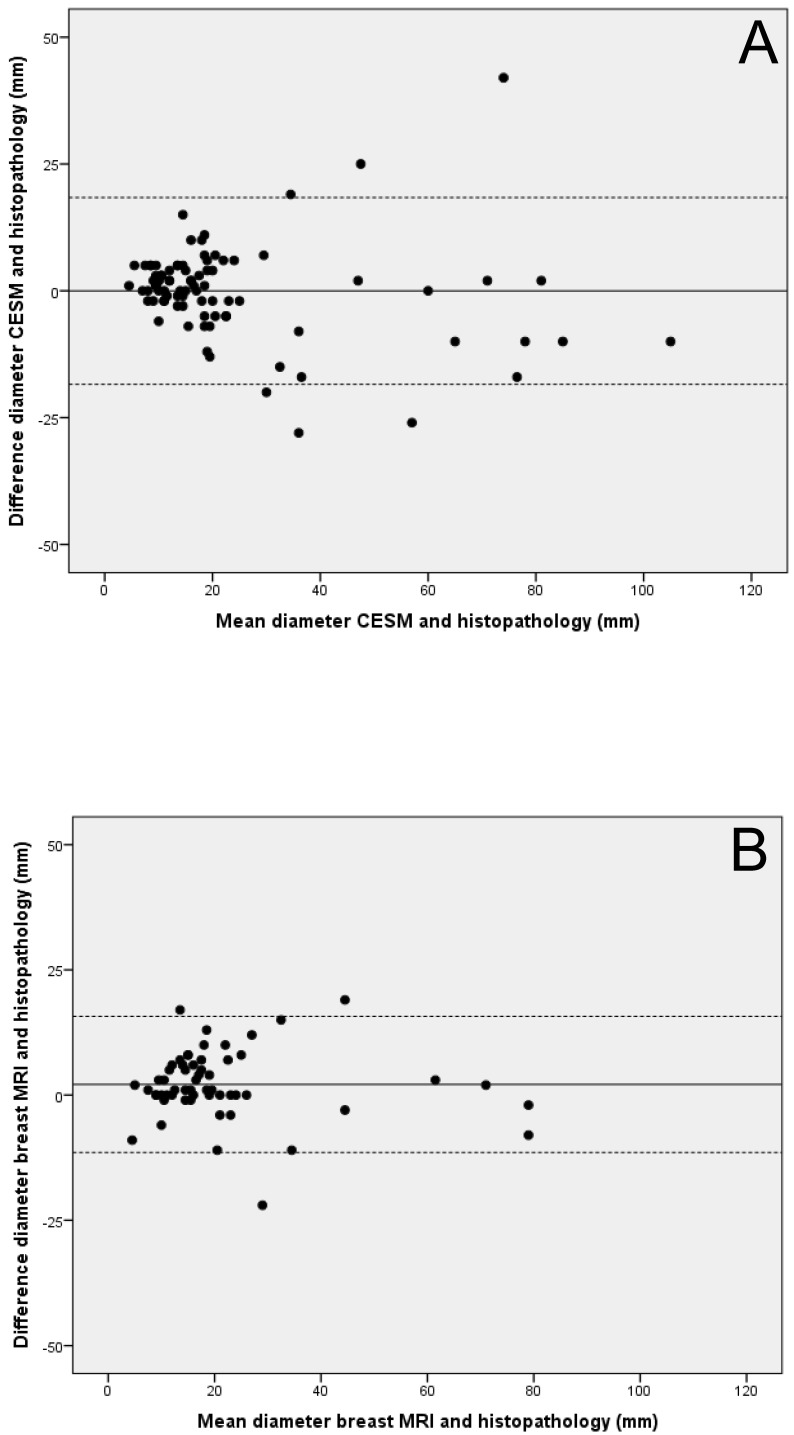

The agreement of maximum tumor diameter measurement between CESM and histopathology, and breast MRI and histopathology is presented in Figure 3. The mean difference between CESM and histopathology was only 0.03 mm, with 95% LOA of -18.44 and 18.40 mm, respectively. The mean difference between breast MRI and histopathology was 2.12 mm, with 95% LOA of -11.46 and 15.71 mm. In short, MRI shows a slight systematic overestimation of the tumor diameter measured, whereas CESM does not. The 95% LOA of breast MRI tumor measurements are smaller than those of CESM.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots for the comparison between (A) CESM and histopathology and (B) breast MRI and histopathology. Continuous lines represent the mean of the differences between measurements, the dotted lines represent upper and lower limits of 1.96 times the standard deviations of differences.

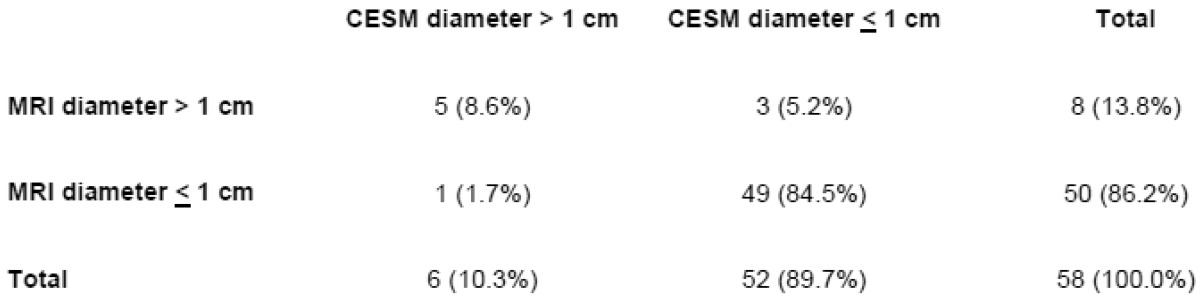

Table 2 shows a 2x2 contingency table displaying the frequency distribution of the studied variables for all 58 lesions that were measured with CESM and breast MRI. In most cases (84.5%), no size discrepancies were observed for both modalities. As is explained on a case-by-case basis below, the addition of breast MRI did not result in more accurate size estimations when compared to CESM.

Table 2.

2×2 contingency table of tumor diameter measurement assessed by CESM or breast MRI.

A relevant size discrepancy was observed for both techniques simultaneously in 5 cases (all invasive ductal carcinomas: four grade II and one grade III carcinoma). In two cases, tumor size was overestimated by both modalities. A 25 mm carcinoma was estimated to be 44 mm on CESM and 40 mm on breast MRI. A 35 mm carcinoma was estimated to be 60 mm on CESM and 54 mm on breast MRI. In three cases, tumor size was underestimated by both modalities. In these cases, the subsequent diameters were 25, 20 and 13 mm for CESM and 29, 18 and 15 mm for breast MRI. Final histopathological analysis showed these tumors to be 40, 40 and 26 mm. Although underestimation of tumor size carries the risk of positive surgical margins, these were not observed in these three cases.

In 3 cases, no relevant size discrepancy was observed for CESM, whereas the addition of breast MRI resulted in an inaccurate size estimation. All cases were invasive ductal carcinomas (two grade I, one grade III carcinomas). All tumor sizes were overestimated by MRI >1 cm. For CESM, tumor diameters were 27, 17 and 10 mm, respectively (versus 21, 12 and 5 mm at histopathological examination). For breast MRI, these measurements were 33, 25 and 22 mm, respectively. In these cases, CESM would already have estimated tumor size accurately and the addition of a breast MRI exam would increase the risk of unnecessary wider tumor excision.

Only one case showed a potential benefit of the addition of breast MRI. This invasive lobular carcinoma's maximum diameter was 13 mm. The diameters measured by CESM and breast MRI were 24 and 23 mm, respectively. Per definition, this resulted in a relevant size discrepancy for CESM and not for breast MRI, but it is obvious that the addition of breast MRI did not have any clinical impact.

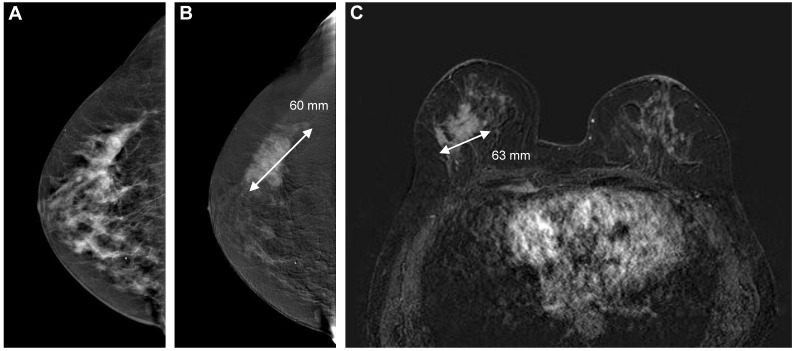

In Figure 4 and 5, examples of good and poor agreement between tumor diameter measurement between CESM and breast MRI can be appreciated.

Figure 4.

Image example of good agreement between tumor diameter measurements using CESM and breast MRI. The cancer is ill-defined on the low-energy CESM image (A) and can be measured more confidently on the recombined image (B, 60 mm). Subtracted contrast-enhanced T1w images (C) showed a similar irregular mass (63 mm). Final pathological results showed a 60 mm invasive ductal carcinoma.

Figure 5.

Example of poor agreement between CESM and breast MRI. The low-energy CESM image (A) shows an ill-defined mass behind the nipple, enhancing on the recombined images (B, 16 mm). Breast MRI showed a spiculated mass (C, 29 mm). Histopathological results showed a 21 mm invasive lobular carcinoma.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the quality of maximum tumor diameter measurements of CESM with histopathologic results as gold standard. Where available, the quality of tumor diameter measurements as assessed by breast MRI was also studied. We demonstrated a good correlation and agreement between these measurements. A 2x2 contingency table showed that the addition of a breast MRI exam after CESM did not yield more accurate tumor diameter measurements in any of the cases.

CESM is a new breast imaging tool that recently became commercially available. The CESM exam provides the radiologist with a so-called low-energy image (which is comparable to a regular mammogram) and a 'recombined' image, in which enhancing structures are visualized 15. In a recent summary review it was shown that CESM was consistently superior to conventional full-field digital mammography 2. However, these studies mainly focused on the ability of CESM to detect breast cancer, not on the quality of maximum tumor diameter measurements (which are essential for surgical planning).

There is only one prior publication that calculated PCC for CESM, breast MRI and histopathology 7. In this study by Fallenberg et al., the PCC for CESM and histopathology was 0.733 (p<0.0001), and 0.654 (p<0.0001) for breast MRI and histopathology. In our study, PCC's were 0.905 (p<0.0001) and 0.915 (p<0.0001) respectively. However, merely calculating the PCC can be misleading, since good correlation does not automatically imply good agreement between measurements of two different modalities 8, 11. If there is a systematic over- or underestimation in the two measurements, PCC can be high, while agreement can be poor. For these comparisons, a Bland-Altman plot might be a more suitable method of presenting the results, since it allows us to evaluate the range and magnitude of measurement errors and shows whether these errors are acceptable in terms of clinical consequences 11. As our Bland-Altman plots show, breast MRI shows a small tendency to overestimate tumor size (mean difference +2 mm), whereas CESM does not. However, the 95% LOA of breast MRI are smaller than CESM. These plots also show that the observed mean differences are in our opinion clinically neglible.

In a 2x2 contingency table, we studied the frequency distribution of relevant size discrepancies between measurements performed using CESM or breast MRI. A relevant size discrepancy was defined as >1 cm between CESM tumor size measurements and the final histopathological tumor size measurement. This approach allowed us to study in the 58 lesions that were measured by both CESM and breast MRI if an additional breast MRI after a CESM exam would results in more accurate tumor size estimations. In the majority of cases, no relevant size discrepancies were observed in both modalities. In three cases, CESM already assessed tumor size accurately, whereas an additional breast MRI exam would result in a larger overestimation of tumor size, resulting in unnecessary excision of healthy breast tissue. In three cases, both CESM and breast MRI underestimated breast cancer size, but this did not result in tumor-positive surgical margins. Only one case of a 13 mm tumor showed a potential benefit of the addition of breast MRI, but this was mainly caused by our predefined cut off value for size discrepancy of 1 cm. In short, this 2x2 contingency table did not show any benefit of additionally performing a breast MRI exam after CESM in any of the cases.

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size of the population is small, which refrained us from studying the ability of CESM to detect multifocal breast cancer in comparison to breast MRI. In a paper by Jochelson et al., CESM was compared to breast MRI with respect to cancer detection rates and false-positive findings, but also for the evaluation of multifocal breast cancer. In this study of 52 cancer cases, 88% of the additional ipsilateral breast cancers were detected by breast MRI, versus 56% detected by CESM 16. Consequently, breast MRI might be more accurate than CESM in detecting multifocal breast cancers. We could not perform any additional analysis on the ability of CESM to detect multifocal breast cancer ourselves due to the limited number of cases (n=4). As a result, there is currently insufficient evidence that CESM can also be reliably used in multifocal breast cancers, and as such additional breast MRI should be considered if multifocal breast cancer is suspected.

Second, studying the agreement between maximum tumor diameter using imaging methods and comparing them to histopathological results has some inherent limitations. For example, tumor diameter may be distorted during the process of removal and fixation of the surgical specimen 17-20. Due to the pliable nature of the breast, tumor diameter may vary depending on patient positioning during imaging exams 19. In addition, orientation of intact specimens so that tumor diameters are measured in the similar planes in histologic analysis as in imaging might be challenging 17. These potential errors in measurements are particularly important in retrospective analyses like our current study, since histopathological tumor size measurements were not performed for the purpose of this study.

Nonetheless, these promising results warrant larger studies which should be performed in multiple centers in order to include sufficient cases of especially multifocal breast cancers. In addition, these studies should also focus on the planned surgical treatment based on the different modalities and study how often the surgical management would be altered for the good or the worse. The results of this study show the potential of CESM as an alternative for tumor size measurements in hospitals with less access the MRI facilities.

In conclusion, the quality of tumor size measurement using CESM is good and the addition of a breast MRI exam for this purpose does not seem beneficial, unless multifocal breast cancer is suspected. CESM might be a suitable alternative for preoperative evaluation of tumor extent. Potential advantages of CESM over breast MRI are the short examination times, easy accessibility and fewer costs. Disadvantages are the use of an iodine based contrast agent instead of a gadolinium based agent and an increase in radiation dose as compared to FFDM 21. However, if multifocal breast cancer is suspected, breast MRI should remain the preferred imaging modality, as there is still insufficient evidence that CESM is equally accurate as breast MRI to assess the extent of multifocal breast cancers.

Abbreviations

- CEDM

contrast-enhanced dual-energy mammography

- CESM

contrast-enhanced spectral mammography

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

- DWI

diffusion-weighted imaging

- FFDM

full-field digital mammography

- LOA

limits of agreement

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PCC

Pearson's correlation coefficient.

References

- 1.Dromain C, Balleyguier C, Adler G. et al. Contrast-enhanced digital mammography. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Francescone MA, Jochelson MS, Dershaw DD. et al. Low energy mammogram obtained in contrast-enhanced digital mammography (CEDM) is comparable to routine full-field digital mammography (FFDM) Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:1350–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobbes MB, Smidt ML, Houwers J. et al. Contrast-enhanced mammography: techniques, current results, and potential indications. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:935–944. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Goethem M, Tjalma W, Schelfout K. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:901–910. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sardanelli F, Boetes C, Borisch B. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast: recommendations from the EUSOMA working group. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1296–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez SI, Scholle M, Buckmaster J. et al. Breast cancer tumor size assessment with mammography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging at a community based multidisciplinary breast center. American Surgeon. 2012;78:440–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallenberg EM, Dromain C, Diekmann F. et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography versus MRI: initial results in the detection of breast cancer and assessment of tumor size. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobbes MB, Nelemans PJ. Good correlation does not automatically imply good agreement: the trouble with comparing tumor size by breast MRI versus histopathology. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:e906–907. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobbes MB, Lalji U, Houwers J. et al. Contrast-enhanced spectral mammography in patients referred from the breast cancer screening programme. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:1668–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nationaal Borstkanker Overleg Nederland (NABON) National guideline breast cancer 2012. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: NABON; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schouten van der Velden AP, Boetes C, Bult P, Wobbes T. Magnetic resonance imaging in size assessment of invasive breast carcinoma with an extensive intraductal component. BMC Med Imaging. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann RM, Bult P, Van Laarhoven HW. et al. Breast cancer size estimation with MRI in BRCA mutation carriers and other high risk patients. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1416–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timmers JM, Van Doorne-Nagtegaal HJ, Zonderland HM. et al. The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) in the Dutch breast cancer screening programme: its role as an assessment and stratification tool. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1717–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2409-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jochelson M. Contrast-enhanced digital mammography. Radiol Clin N Am. 2014;52:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jochelson MS, Dershaw DD, Sung JS. et al. Bilateral contrast-enhanced dual-energy digital mammography: feasibility and comparison with conventional digital mammography and MR imaging in women with known breast cancer. Radiology. 2013;266:743–751. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12121084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Provencher L, Dioro C, Hogue JC. et al. Does breast cancer tumor size really matter that much? Breast. 2012;21:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behjatnia B, Sim J, Bassett LW. et al. Does size matter? Comparison study between MRI, gross, and microscopic tumor sizes in breast cancer in lumpectomy specimens. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;22:303–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pritt B, Tessitore JJ, Weaver DL. et al. The effect of tissue fixation and processing on breast cancer size. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:756–760. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker FL. Imaging-assisted large-format breast pathology: program rationale and development in a nonprofit health system in the United States. Int J Breast Cancer. 2012. 171792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jeukens CR, Lalji UC, Meijer E. et al. Radiation exposure of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography compared to full field digital mammography. Invest Radiol. 2014;49:659–665. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]