Abstract

Bariatric procedures, associated with gastrointestinal malabsorption of vitamins and microelements, may constitute a risk factor for nutritional optic neuropathy (NON). We present a case of a 34-year-old female patient who developed bilateral NON after sleeve gastrectomy. Despite postoperative ophthalmological supervision, 10 months after the procedure the woman presented with a bilateral decrease in visual acuity down to 0.8, bilateral visual field loss and abnormal visual evoked potential recordings. Laboratory abnormalities included decreased serum concentration of vitamin B12 (161 pg/ml). Treatment was based on intramuscular injections of vitamin B12 (1000 units per day). After 1 week of the treatment, we observed more than a three-fold increase in the serum concentration of vitamin B12 and resolution of the bilateral symptoms of NON. The incidence of NON is likely to increase due to the growing number of these bariatric procedures performed worldwide. Therefore, all persons subjected to such surgery should receive long-term ophthalmological follow-up and supplementation with vitamins and microelements.

Keywords: nutritional optic neuropathy, sleeve gastrectomy, vitamin B12 deficiency

Introduction

Nutritional optic neuropathy (NON) results from complete lack or insufficient dietary supply of nutrients vital for normal functioning of nerve fibers. This is usually associated with vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency due to unbalanced diet, undernutrition, chronic alcoholism or malignant anemia [1, 2]. Aside from these well-established risk factors, bariatric procedures emerged recently as a new cause of NON due to the worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity. According to epidemiological data, a considerable percentage of humans (e.g. up to one-third of the US population) are obese. Obesity leads to serious medical complications, such as arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, etc. [3, 4]. Therefore, management of obesity constitutes a serious challenge for modern medicine. Bariatric surgery remains the only option in the case of morbidly obese patients who did not respond to conservative methods of treatment. This places bariatric surgery among the most rapidly expanding surgical disciplines. The aim of bariatric surgery is to reduce body weight via limited gastrointestinal absorption of nutrients or decreased dietary intake thereof. However, despite their many positive effects, these procedures are also associated with significant risks resulting from malabsorption of nutrients, especially vitamin B complex (B1, B6 and B12), folic acid, vitamin D, vitamin E, zinc and copper [5–7]. Shortage of these vitamins exerts an unfavorable effect on functioning of the neural tissue. According to the literature, up to 16% of patients after various types of bariatric procedures suffer from neurological complications [8–10]. However, little is known about the effects of bariatric procedures on the function of the optic nerve. Sparse literature data point to potential risk of NON in patients subjected to bariatric procedures [11, 12]. Nutritional neuropathies develop slowly and “insidiously”, and can lead to permanent loss of vision when diagnosed too late and/or left untreated. Therefore, individuals subjected to bariatric procedures should be subject to continuous ophthalmological surveillance, and the evidence of any early signs of NON should constitute an indication for appropriate supplementation with vitamins.

To emphasize the importance of the problem in question, we present a case of a female patient after sleeve gastrectomy who developed bilateral NON despite postoperative ophthalmological follow-up.

Case report

A 34-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Ophthalmology, Medical University of Bialystok, due to a 2-week history of gradually progressing, bilateral symmetrical loss of visual acuity. The patient had no previous history of ophthalmic disorders, systemic conditions or injuries, and apart from oral contraceptives did not take any medications on a regular basis. She did not smoke, and drank alcohol only sporadically. Ten months earlier the patient was subjected to uncomplicated sleeve gastrectomy. Prior to the procedure, her body weight and body mass index (BMI) were 120 kg and 41.5 kg/m2, respectively; body weight and BMI determined on admission to the Department of Ophthalmology were 65 kg and 22.5 kg/m2, respectively. Both prior to the bariatric surgery and after the procedure, the patient was consulted by an ophthalmologist. The examination included basic ophthalmological tests and visual field testing, with particular emphasis on optic nerve function. The status determined at the postoperative examination constituted the baseline for further follow-up. The woman was supervised by specialists from the Surgical and Ophthalmology Outpatient Departments. Follow-up ophthalmological examinations were scheduled 1, 3 and 6 months after the bariatric surgery. As no abnormalities were found during these visits, the next check-up was scheduled in 6 months; however, the patient was asked to refer earlier if any alarming eye symptoms emerged. Therefore, she referred 4 months after the last visit due to a decrease in visual acuity and was admitted for detailed evaluation at the Department of Ophthalmology.

An ophthalmological examination performed at the time of admission revealed a bilateral decrease in distance visual acuity down to 0.8 (norm: 1.0), normal bilateral near visual acuity, normal color perception with somewhat lower saturation on the Ishihara color test, normal intraocular pressure and symmetrical pupillary reflexes. No abnormalities were found in the anterior and posterior segments of the eyes, including both optic nerve discs. Additional neuro-ophthalmic tests, such as pattern visual evoked potential (pattern VEP) testing and computerized static perimetry, were conducted to examine the optic nerve function. Pattern VEP recordings were characterized by bilaterally decreased amplitudes with normal latencies, corresponding to impaired neural transmission in the optic fibers (Figures 1, 2). Perimetry revealed peripheral, usually inferior, scotomas in both eyes, located 40–60° from the vertical meridian (Figures 3, 4). The results of the optical coherence tomography of the maculae and optic nerve discs were normal. Further evaluation of the patient included laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging. The list of documented abnormalities included decreased serum concentration of vitamin B12 (161 pg/ml, normal limit: 187–883 pg/ml) and presence of nitrates and ketone bodies in the urine. The remaining parameters of the blood (complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, protein electrophoresis, lipid profile, 24-h glycemic profile, coagulation profile, activities of liver and pancreatic enzymes, bilirubin level, concentrations of folic acid, zinc, copper, magnesium and iron) were normal. Furthermore, no pathologies of the visual pathway were detected on the computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the head and orbits. Heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature of the patient remained normal throughout the entire hospitalization period. Also neurological examination did not show any abnormalities.

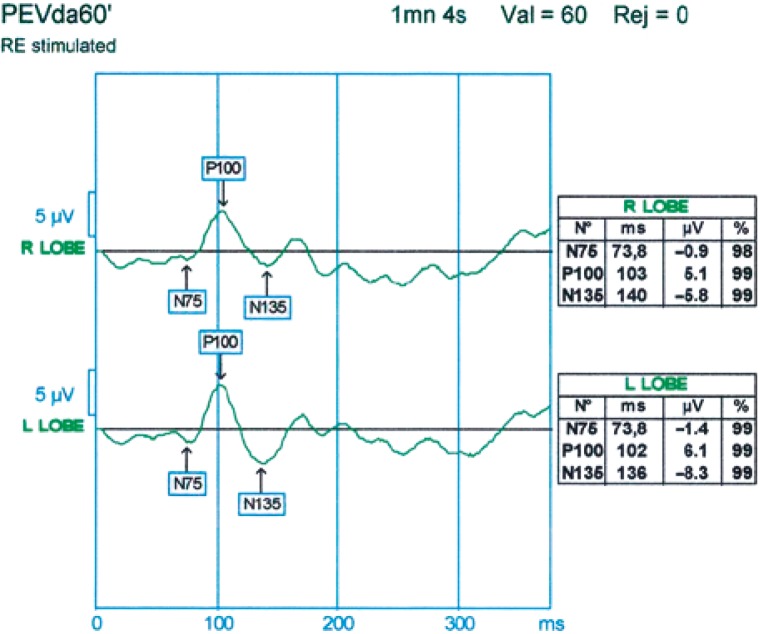

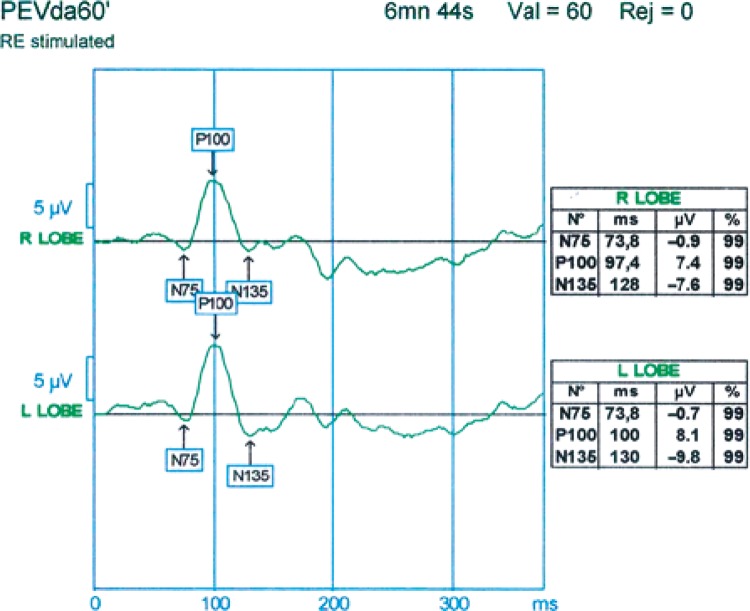

Figure 1.

Visual evoked potential recording from the right eye: decreased amplitude of P100 wave (5.1 µV over the right hemisphere and 6.1 µV over the left hemisphere)

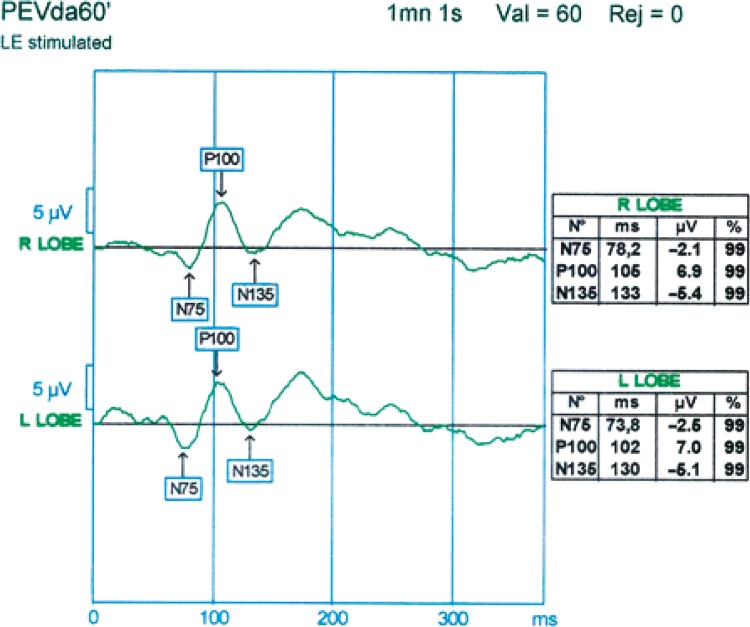

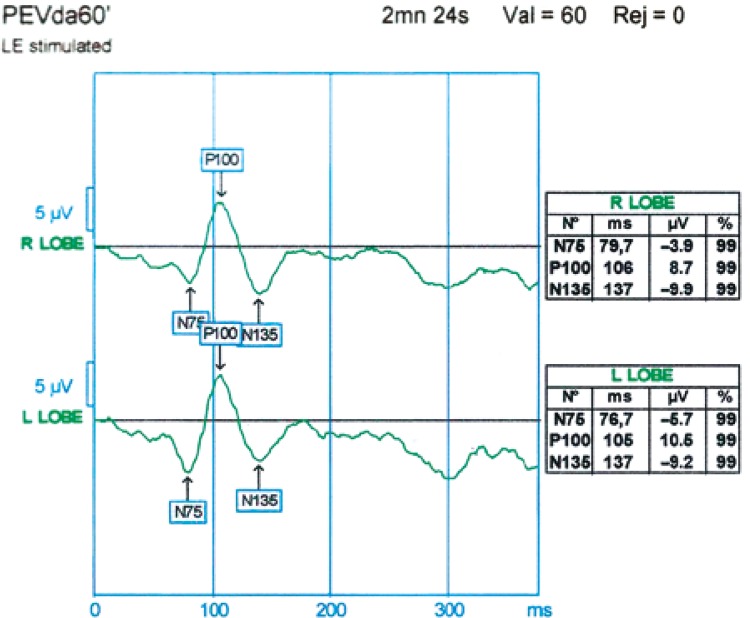

Figure 2.

Visual evoked potential recording from the left eye: decreased amplitude of P100 wave (6.9 µV over the right hemisphere and 7.0 µV over the left hemisphere)

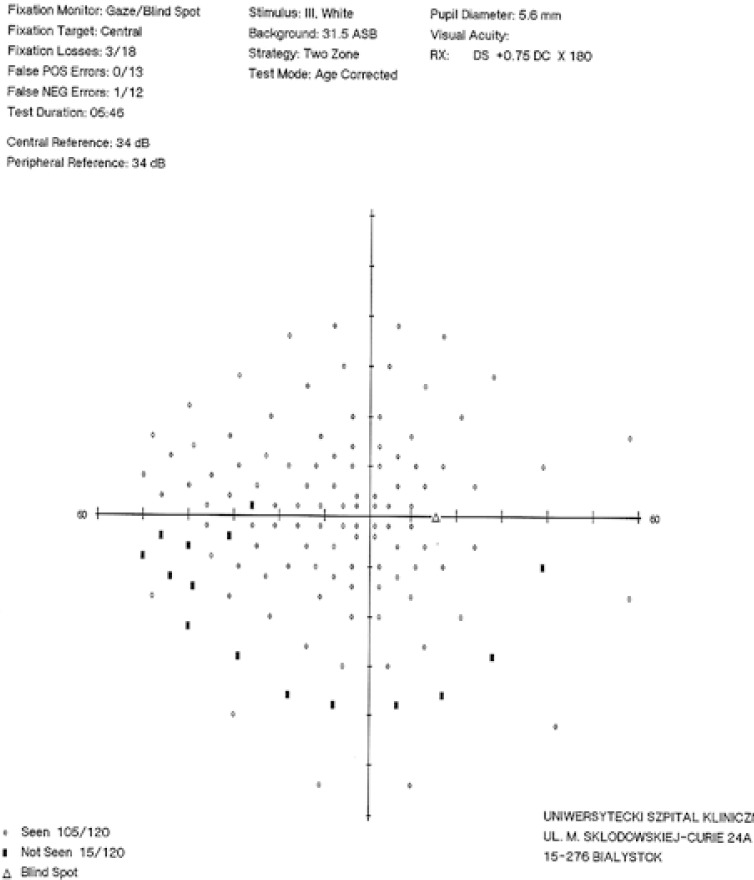

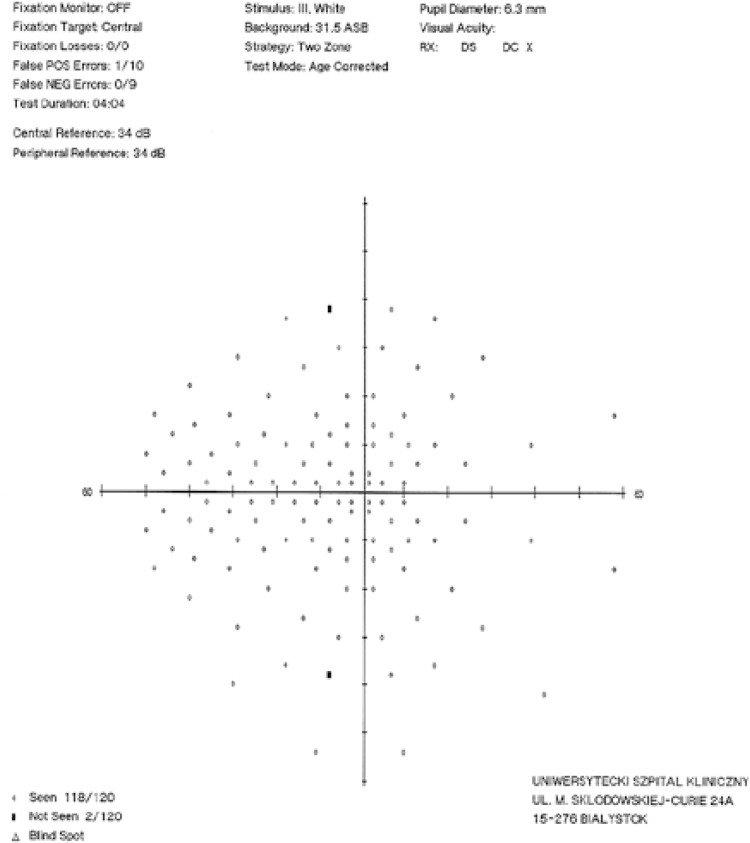

Figure 3.

Visual field of the right eye at the time of admission: inferior arcuate scotoma located 40° from the vertical meridian

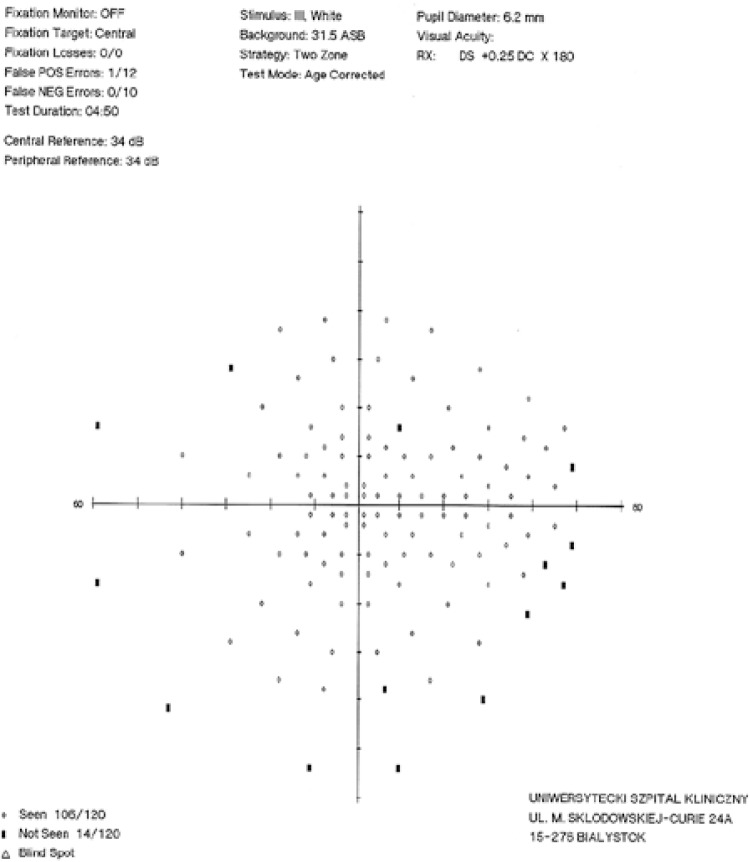

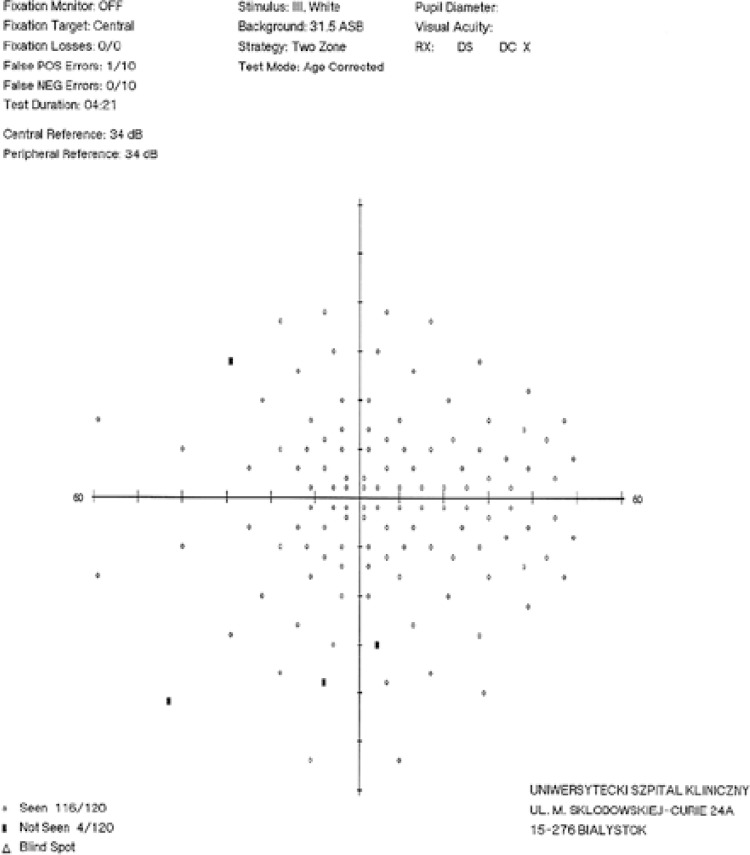

Figure 4.

Visual field of the left eye at the time of admission: peripheral scotoma located 40– 60° from the vertical meridian

On the basis of the abovementioned tests, the patient was diagnosed with bilateral nutritional neuropathy associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. The treatment was based on a well-balanced diet rich in protein and vitamin B complex, and intramuscular injections of vitamin B12 (1000 units per day for 7 days). Considerable improvement of bilateral visual acuity and resolution of the previously reported subjective ophthalmic ailments were documented after one week of the treatment. Serum concentration of vitamin B12 increased more than three-fold, up to 517 µg/dl. VEP recordings were normal (Figures 5, 6), and most of the previously documented visual field abnormalities resolved (Figures 7, 8). The patient was discharged home with normal visual acuity in both eyes. She was prescribed a well-balanced, protein- and vitamin-rich diet, along with additional oral supplementation with vitamin B12. Although the patient does not present any ophthalmic problems 3 months after the discharge, she is still being followed up at both Ophthalmology and Surgical Outpatient Departments.

Figure 5.

Visual evoked potential recording from the right eye: normal amplitude of P100 wave over both hemispheres

Figure 6.

Visual evoked potential recording from the left eye: normal amplitude of P100 wave over both hemispheres

Figure 7.

Visual field of the right eye after supplementation with vitamin B12

Figure 8.

Visual field of the left eye after supplementation with vitamin B12

Discussion

Although bariatric procedures are among the most effective methods for treatment of morbid obesity, they are also associated with the risk for neurological complications [6, 9, 10, 13, 14]. The latter may result from malabsorption or dietary shortage of nutrients that are crucial for normal functioning of neural tissue. The present case of a young woman constitutes an excellent example of such a deficiency-related complication. Ten months after uncomplicated sleeve gastrectomy, the patient developed bilateral NON associated with vitamin B12 deficiency. Usually persons after bariatric procedures are not offered any additional supplementation with vitamins and microelements. While this was also the case of our patient, postoperative follow-up at the Ophthalmology Outpatient Department enabled us to detect initial early symptoms of the disorder. Supplementation with vitamin B12 at an appropriate dose resulted in rapid resolution of the ophthalmic abnormalities and improvement of the local status. However, it should be remembered that nutritional optic neuropathy is not always reversible. This was shown by Chacko et al. [11], who published a case of a female patient with the symptoms of NON associated with folic acid and vitamin B complex deficiency, diagnosed 3 years after a bariatric procedure. The symptoms did not resolve despite implementation of appropriate supplementation, which was probably a consequence of too late diagnosis. Chronic uncompensated vitamin deficiency leads to gradual albeit persistent and irreversible destruction of the optic nerve fibers.

Ophthalmic disorders manifesting in a longer perspective, i.e. within months or even years after bariatric surgery, constitute a new medical problem. However, the issue is likely to expand due to the growing number of these procedures performed worldwide. Thus, the principal question arises, concerning the purposefulness of postoperative supplementation with vitamins and microelements: should the supplementation be given to all patients after bariatric procedures, or only to those presenting with symptoms of deficiency? When trying to answer this question, one should remember that ophthalmic consequences of the deficiency can be irreversible if diagnosed too late.

Conclusions

One potential solution of this problem can be long-term ophthalmological follow-up of persons subjected to bariatric procedures, being a routine practice in our department. Due to complex, ophthalmological, surgical and neurological postoperative care continued for many months or even years after the procedure, all its potential complications can be detected at their early, reversible stages. Probably only the results of such long-term follow-up will unambiguously explain whether supplementation with vitamins and microelements should be used in all individuals operated on due to morbid obesity.

References

- 1.Glaser J. Nutritional and toxic optic neuropathies. In: Glaser J, editor. Neuro-ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orssaud C, Roche O, Dufier JL. Nutritional optic neuropathies. J Neurol Sci. 2007;262:158–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hady HR, Dadan J, Golaszewski P, et al. Impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on body mass index, ghrelin, insulin and lipid levels in 100 obese patients. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2012;7:251–9. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.28979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jastrzebska-Mierzynska M, Ostrowska L, Hady HR, et al. Assessment of dietary habits, nutritional status and blood biochemical parameters in patients prepared for bariatric surgery: a preliminary study. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2012;7:156–65. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.27581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinazzi M, De Lazzari F, Tavolato B, et al. Myelo-optico-neuropathy in copper deficiency occurring after partial gastrectomy. Do small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome and occult zinc ingestion tip the balance? J Neurol. 2007;254:1012–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker DA, Balcer LJ, Galetta SL. The neurological complications of nutritional deficiency following bariatric surgery. J Obes. 2012;2012:608534. doi: 10.1155/2012/608534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos-Levi AM, Sanchez-Pernaute A, Rubio Herrera MA. Dermatitis and optic neuropathy due to zinc deficiency after malabsortive bariatric surgery. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28:1345–7. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.4.6606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thaisetthawatkul P, Collazo-Clavell ML, Sarr MG, et al. A controlled study of peripheral neuropathy after bariatric surgery. Neurology. 2004;63:1462–70. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142038.43946.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koffman BM, Greenfield LJ, Ali II, et al. Neurologic complications after surgery for obesity. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:166–76. doi: 10.1002/mus.20394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juhasz-Pocsine K, Rudnicki SA, Archer RL, et al. Neurologic complications of gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Neurology. 2007;68:1843–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262768.40174.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chacko JG, Rodriguez CJ, Uwaydat SH. Nutritional optic neuropathy status post bariatric surgery. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2012;36:165–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah AR, Tamhankar MA. Optic neuropathy associated with copper deficiency after gastric bypass surgery. Retinal Cases and Brief Reports. 2014;8:73–6. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger JR. The neurological complications of bariatric surgery. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1185–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.8.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hady HR, Dadan J, Soldatow M, et al. Complications after laparoscopic gastric banding in own material. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2012;7:166–74. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.27605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]