Abstract

Introduction:

Nursing has been identified as an occupation that has high levels of stress. Job stress brought about hazardous impacts not only on nurses’ health but also on their abilities to cope with job demands.

Objectives:

This study aimed at finding out the degree of work-related stress among the staff nurses and various determinants, which have a impact on it.

Materials and Methods:

Institutional-based cross-sectional study conducted on GNM qualified nurses. Predesigned and pre-tested questionnaire covering their sociodemographic variables in part I and professional life stress scale by David Fontana in part II. Analysis used was Chi-square test and logistic regression for various factors.

Results:

Risk for professional stress due to poor and satisfactory doctor's attitude was found about 3 and 4 times more than with excellent attitude of doctors toward the staff nurses. A statistically significant association (P < 0.024) between department of posting and level of stress. Nurses reported that they had no time for rest, of whom 42% were suffering from moderate-to-severe stress. The nurses who felt that the job was not tiring were found to be less stressed as those who perceived job as tiring (OR = 0.43).

Conclusion:

The main nurses’ occupational stressors were poor doctor's attitude, posting in busy departments (emergency/ICU), inadequate pay, too much work, and so on. Thus, hospital managers should initiate strategies to reduce the amount of occupational stress and should provide more support to the nurses to deal with the stress.

Keywords: Professional stress, staff nurse, interpersonal relationship

INTRODUCTION

Occupational stress is a recognized problem in health care workers.[1] Nursing has been identified as an occupation that has high levels of stress.[2]

It was found that job stress brought about hazardous impacts not only on nurses’ health but also in their abilities to cope with job demands. This seriously impairs the provision of quality care and the efficacy of health services delivery.[3,4] Nursing has been identified by a number of studies as a stressful occupation.[5,6] Stress has a cost for individuals in terms of health, wellbeing, and job satisfaction, as well as for the organization in terms of absenteeism and turnover, which in turn may impact the quality of patient care.[7,8]

Stress has been categorized as an antecedent or stimulus, as a consequence or response, and as an interaction. It has been studied from many different frameworks. For example, Selye[9] proposed a physiological assessment that supports considering the association between stress and illness. Conversely, Lazarus and Folkman[10] advocated a psychological view in which stress is “a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her wellbeing.”

Stress is not inherently deleterious, however. Each individual's cognitive appraisal, their perceptions, and interpretations, gives meaning to events and determines whether events are viewed as threatening or positive.[10] Personality traits also influence the stress equation because what may be overtaxing to one person may be exhilarating to another.[11]

In fact, occupational stress has been cited as a significant health problem.[12,13,14] Work stress in nursing was first assessed by Menzies[15] who identified four sources of anxiety among nurses: Patient care, decision making, taking responsibility, and change. The nurse's role has long been regarded as stress-filled based on the physical labor, human suffering, work hours, staffing, and interpersonal relationships that are central to the work nurses do. Since the mid-1980s, nurses’ work stress has been escalating due to the increasing use of technology, continuing rises in health care costs,[16] and turbulence within the work environment.[17]

Most people can cope with stress for short periods but Chronic stress produces prolonged changes in the physiological state.[18] The issues of job stress, coping, and burnout among nurses are of universal concern to all managers and administrators in the area of health care.[2] All these stresses can be modified in a positive way by the use of appropriate stress management skills.

Thus, this study aimed at finding out (1) the degree of professional stress among the staff nurses and (2) various determinants, which have an impact on it so that strategies to improve their personal and professional quality of life can be planned out in the long run.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It is an Institutional-based cross-sectional study, conducted in the year 2013-2014. Place of the study is Swami Vivekanand Hospital, attached to Subharti Medical College, Meerut. It is a tertiary hospital. Study population comprised of nursing staff working in the hospital. Study unit included in the study was the GNM qualified nurse. All the GNM qualified nurses working in the day or night shift were covered by consequential sampling technique; and all those who were on leave or not available at the time of data collection twice were excluded from the study. Thus, the total sample size of the study comprised of 100 staff nurses.

Data collection technique: Predesigned and pre-tested, and validated questionnaire in English and Hindi by the experts was administered. It had two parts:

Part I: Covering their sociodemographic variables and variables on their working environment, including attitude of the different category of working staff, salary, job condition, and so on.

Part II: Including Professional life stress scale by David Fontana, The British Psychological Society and Routledge Ltd, Leicester, England, 1989. It consists of 22 questions. It has covered different variables like personality perception by others, optimism for life, satisfaction to self and work, adjustment with the professional environment, and so on. A total score 60, was classified into

0–15: Stress is not a problem in life

16–30: Moderate stress, which can reasonably be reduced

31–45: Stress is clearly a problem and needs remedial action

46–60: Stress is a major problem and something must be done.

Quality Assurances of the data collection: Data were collected by the well-trained and well-qualified two primary investigators themselves.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Stress up to a certain extent, will improve peoples’ performance and quality of life because it is healthy and essential that they should experience challenges within their lives,[19] but if pressure becomes excessive, it loses its beneficial effect and become harmful,[20] because it is the reaction of people under pressure or other types of demands placed on them and arise when they worry that they cannot cope.[21]

It is important that stress is a state, not an illness, which may be experienced as a result of an exposure to wide range of work demands and in turn can contribute to an equally wide range of outcomes,[22] which may concern the employees’ health and be an illness or an injury or changes in his/her behavior and lifestyle.

Interpersonal relationships and stress

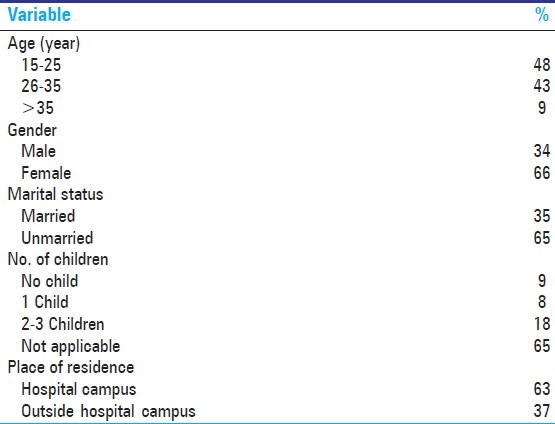

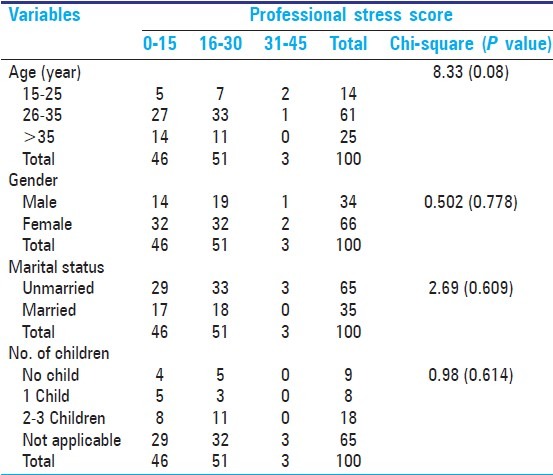

In our study, 91% staff nurses were younger than 35 years with a mean age of 27.41 years (SD = 7.06), 34% were male nurses. One third staff nurses were married and out of them 18% had 2 or 3 children. Work life, however, is not independent from family life; these domains may even be in conflict [Table 1].[23,24] In our study professional stress was not significantly associated with socio-demographic factors like age, marital status, no of children and gender of the staff nurse [Table 2].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the study subjects: (N=100)

Table 2.

Socio-demographic determinants for professional stress

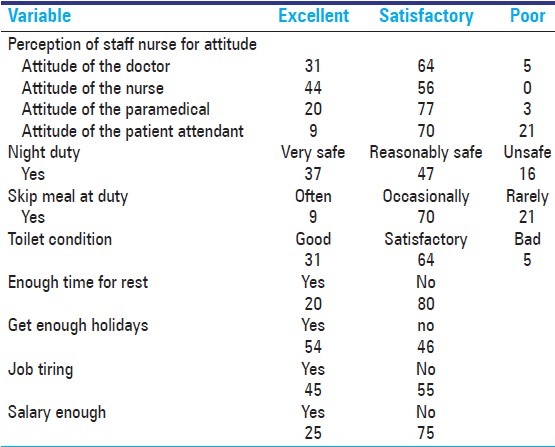

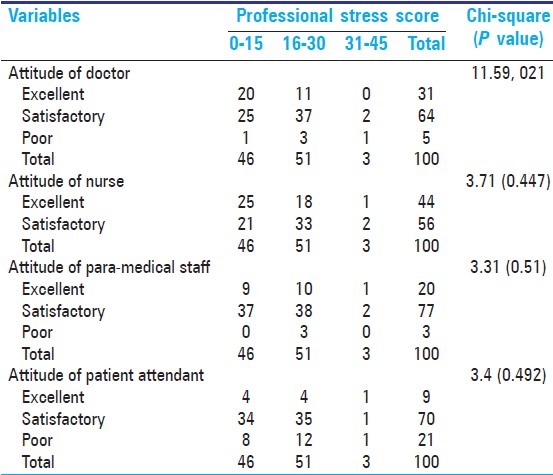

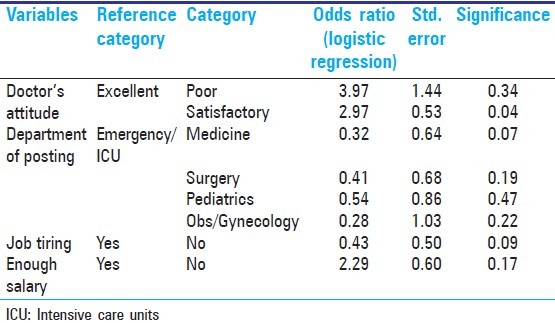

Study has revealed for poor doctors attitude has been perceived by 5% staff nurse, whereas 21% perceive poor attitude from patients side [Table 3]. Doctors attitude was perceived as significant association with professional stress [Table 4]; and risk for professional stress due to poor and satisfactory doctor's attitude was found about 3 and 4 times more than with excellent attitude of doctors toward the staff nurses (OR = 2.97 and OR = 3.97, respectively). Similarly, Blair and Littlewood emphasized that work relationships are potential stressors.[25] In a study of 260 RNs, conflict with physicians was found to be more psychologically damaging than conflict within the nursing profession [Table 5].[26]

Table 3.

Perception of staff nurses regarding working environment

Table 4.

Association between interpersonal relationship and professional stress

Table 5.

Strength of association between interpersonal relationships and working environment and professional stress

Verbal abuse from physicians was noted to be stressful for staff nurses.[27] Similarly, Adib-Hajbaghery and colleagues found that poor relationships between nurses and other health care professionals is a major source of occupational stress among hospital nurses.[28] French and colleagues[29] identified conflict with physicians, problems with peers and supervisors, and discrimination as stressors for nurses. Thus, developing good personal relationship at work place is necessary for the prevention of job stress among hospital nurses.

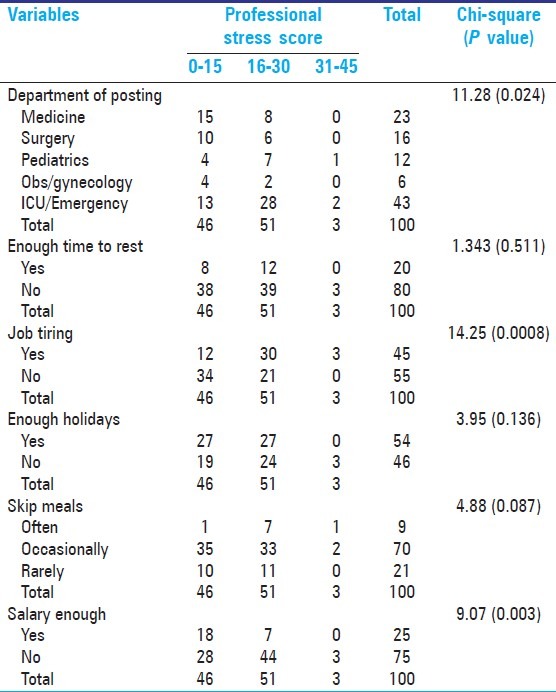

Association between department of posting and stress

The target study revealed a statistically significant association (P < 0.024) between department of posting and level of stress [Table 6]. Majority (43%) of the nurses posted in the emergency/ICU department were stressed out, of whom 2% were severely stressed. It was found that staff nurses posted in medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and obs/gynecology department were less stressed as compared with those posted in the emergency/ICU department (OR = 0.32; 0.41; 0.54; 0.28, respectively) [Table 5]. In another study, a statistical significant association was seen between nurses’ occupational stress and their area of work or specialty (P < 0.01). The mean score of nurses’ occupational stress in the psychiatry ward (3.86), ICU (3.43), operation theater (3.45), pediatrics (3.41), cardiology (3.35), internal medicine (3.34), surgery (3.30), accident and casualty department (3.27), obstetrics (3.26), orthopedics (3.24), and CCU (3.21) were high. Nurses working in intensive care units ranked insufficient regular breaks, work shifts, too much work, and staff shortage as the main sources of distress. Nurses in medical, surgical care units, and operation theaters ranked workload, time pressure, staff shortage, and lack of management and co-workers’ support more stressful.[30] Similarly, Rahmani and colleagues reported high job stress in ICU nurses in Tabriz University Hospitals, Iran.[31]

Table 6.

Association between working environment and professional stress

Association between working conditions and stress

In the current study, as high as 80% nurses reported that they had no time for rest, out of which 42% were suffering from moderate-to-severe stress, whereas 45% said that they found their job tiring, out of whom 33% were under moderate-to-severe stress [Table 6]. Also, the staff nurses who felt that the job was not tiring were found to be less stressed as those who perceived job as tiring (OR = 0.43). Inadequate salary was also one of the key factors causing stress as perceived by 75% nurses (OR = 2.29) [Table 5]. Similarly, too much work to do and inadequate staff to cover duties were the most significant associated factors of stress for Iranian nurses.[30] Several studies have highlighted work overloads and time pressure as significant contributors to work stress among health care professionals[32,33] An excessive workload increases job tension and decreases job satisfaction, which in turn, increases the likelihood of turnover.[34,35] A study by Ali Mohammad Mosadeghrad among Iranian nurses revealed excessive workload (3.72), and time pressure (3.63) as one of the major factors leading to stress in terms of mean scores of occupational stress among them.[30]

CONCLUSION

The level of occupational stress among a group of Indian staff nurses was measured using a questionnaire survey and professional stress scale and GHQ were applied. In addition, factors contributing to occupational stress were examined. Hospital nurses in this study reported moderate (51%) to severe (3%) levels of job-related stress. The main nurses’ occupational stressors were poor doctor's attitude, posting in busy departments (emergency/ICU), inadequate pay, too much work, time pressure, and tiring job with insufficient time for rest and meals. Stress decreases attention, concentration, and decision making, and judgment skills. Occupational stress is also negatively related to quality of care due to loss of compassion for patients and increased incidences of mistakes and practice errors. Thus, hospital managers should initiate strategies to reduce the amount of occupational stress among the nurses. They should provide more support to the nurses to deal with the stress.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Subharti Medical College

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burbeck R, Coomber S, Robinson SM, Todd C. Occupational stress in consultants in accident and emergency medicine: A national survey of levels of stress at work. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:234–8. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.3.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xianyu Y, Lambert VA. Investigation of the relationships among workplace stressors, ways of coping, and the mental health of Chinese head nurses. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8:147–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JK. Job stress, coping and health perceptions of Hong Kong primary care nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9:86–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1322-7114.2003.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrington A. Stress and nursing. Br J Nurs. 1995;4:574–8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1995.4.10.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall J. Stress amongst nurses. In: Cooper CL, Marshall, editors. White Collar and Professional Stress. London, Chicester: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey RD. Coping with stress in caring. Oxford: Blackwell; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price JL, Mueller CW. Professional turnover: The case for nurses. New York: New Medical and Scientific Books; 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cronin-Stubbs D, Brophy EB. Burnout: Can social support save the psychiatric nurses? J Psychosoc Nurs Mental Health Serv. 1985;23:8–13. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19850701-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selye H. The stress of life. New York: McGraw Hill; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.French JR, Caplan RD. Organizational stress and individual strain. In: Marrow AJ, editor. The failure of success. New York: AMACOM; 1972. pp. 30–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caplan RD, Cobb S, French JR, John RP, Harrison RV, Pinneau SR., Jr . Job demands and worker health: Main effects and occupational differences. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.House JS. Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelletier KR. Healthy people in unhealthy places. New York: Delacorte Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzies IE. Nurses under stress. Internatl Nurs Rev. 1960;7:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jennings BM. Stressors of critical care nursing. In: Thelan LA, Davie JK, Urden LD, editors. Critical care nursing Diagnosis and management. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1994. pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jennings BM. Turbulence. In: Hughes R, editor. Advances in patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2007. pp. 2-193–2-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang EC, Tugade MM, Asakawa K. Stress and coping among Asian Americans: Lazarus and Folkman's model and beyond. In: Wong PT, Wong LC, editors. Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tehrani N, Ayling L. Work-related stress. CIPD Stress at work. 2009. Jun, [Lat accessed on 2008 Jan 12]. Available from: http://www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/health/stress/stress.htm .

- 20.Cooper CL, Cooper RD, Eaker LH. Living with stress. Harmonsworth: Penguin; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tackling work related stress: A managers’ guide to improving and maintaining employee health and well-being. Sudbury: HSE Books; 2001. Health and safety executive. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doherty N, Tyson S. Mental well-being in the workplace: A resource park for management, training and development. Sudbury: HSE Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Near JP, Rice RW, Hunt RG. The relationship between work and nonwork domains: A review of empirical research. Acad Manage Rev. 1980;5:415–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearlin LI. Kaplan HB. Psychological stress Trends in theory and research. New York: Academic Press; 1983. Role strains and personal stress; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blair A, Littlewood M. Sources of stress. J Community Nurs. 1995;40:38–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillhouse JJ, Adler CM. Investigating stress effect patterns in hospital staff nurses: Results of a cluster analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1781–8. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00109-3. 9447628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13:48–55. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(97)80026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Khamechian M, Masoodi Alavi N. Nurses’ perception of occupational stress and its influencing factors: A qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:352–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.French SE, Lenton R, Walters V, Eyles J. An empirical evaluation of an expanded nursing stress scale. J Nurs Meas. 2000;8:161–78: 9183112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosadeghrad AM. Occupational Stress and Turnover Intention: Implications for Nursing Management. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1:169–76. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmani F, Behshid M, Zamanzadeh V, Rahmani F. Relationship between general health, occupational stress and burnout in critical care nurses of Tabriz teaching hospitals. 2010;23:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Ploeg E, Kleber RJ. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: Predictors of health symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(Suppl 1):i40–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Aameri AS. Source of job stress for nurses in public hospitals. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1183–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strachota E, Normandin P, O’Brien N, Clary M, Krukow B. Reasons registered nurses leave or change employment status. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33:111–7. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]