Abstract

Common explanations for the generally negative relationship between education and ethnic endogamy include (1) education makes immigrants and their children better able to adapt to native culture thereby eliminating the need for a same-ethnicity spouse and (2) education raises the likelihood of leaving ethnic enclaves, thereby decreasing the probability of meeting potential same-ethnicity spouses. This paper considers a third option, the role of assortative matching on education. If education distributions differ by ethnicity, then spouse-searchers may trade similarities in ethnicity for similarities in education when choosing spouses. U.S. Census data on second-generation immigrants provide strong support for the assortative matching mechanism.

I. INTRODUCTION

Despite a widespread perception that education positively affects the social assimilation of immigrants and their children, the driving forces behind this relationship are not well understood. This paper examines the mechanisms through which education affects the probability of interethnic marriage,1 one specific measure of social integration. Particular attention is given to the role of assortative matching on education in explaining marriage patterns of second-generation immigrants.

In a series of papers, Borjas explains the slow assimilation of immigrants using the concept of ethnic externalities. Put simply, if immigrants associate predominantly with members of their ethnic groups, then the descendents of immigrants growing up in better ethnic environments, as measured by average years of schooling, for example, will be more successful later in life. In this way, ethnic externalities can slow the upward mobility of members of low-skilled immigrant groups and the downward mobility of members of high-skilled groups (Borjas 1992, 1993, 1995).

Assimilation can be further slowed if social interactions are primarily between people with similar education levels. If high education members of low-skilled ethnic groups do not associate with their ethnic networks, then they will not serve as role models and mentors for the next generation. Similarly, if low education members of high-skilled immigrant groups do not associate with their ethnic communities, then the downward mobility of advantageous ethnic groups can also be further slowed. If we interpret intermarriage as a measure of the broader social integration of immigrants, then knowledge of the importance of assortative matching on education in marriage markets can inform our understanding of the intergenerational immigrant assimilation process more generally. For example, if high education members of low education ethnic groups systematically marry outside of their ethnicity because of a lack of similarly educated co-ethnics, the resulting decrease in their association with co-ethnics may lead to fewer high-skilled co-ethnic role models for the younger generation.

The relationship between education and intermarriage may also help to explain why intergenerational assimilation rates of certain immigrant groups appear rather low. Duncan and Trejo (2009) suggest that if education is positively related to out-marriage and if children of intermarried parents are less likely to identify with any specific ethnicity, then standard estimates of intergenerational assimilation may be biased downward. Duncan and Trejo find empirical evidence of this for Mexican Americans. Although my results are consistent with those of Duncan and Trejo for Mexicans, the relationship between education and out-marriage is negative for certain other ethnic groups. Knowledge of the different mechanisms through which education affects intermarriage can help researchers appropriately interpret estimates of intergenerational progress of different immigrant groups.

Previous empirical studies of the relationship between education and intermarriage have produced mixed results. A number of authors have found a positive relationship (Chiswick and Houseworth, 2008; Cohen, 1977; Lichter and Qian, 2001; Meng and Gregory, 2005; Qian, 1997). However, Hwang, Saenz, and Aguirre (1995) find that Asian women with lower levels of education are more likely to out-marry racially. Kitano et al. (1984) find no relationship between occupational status and out-marriage for Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans in California. Based on another set of studies, Lieberson and Waters (1988) concluded that the influence of education on ethnic endogamy is small. To reconcile all of these seemingly contradictory findings, it is necessary to examine the various pathways through which education affects ethnic endogamy.

Using the insights provided by Wong (2003) and Gullickson (2006) in their papers on racial intermarriage, I argue that the mechanisms through which human capital affects ethnic endogamy fall into three main categories. First, education may improve immigrants’ abilities to adapt to the customs of the host country. For example, educated immigrants may be more fluent in the host country’s language, enabling them to share a household with a native more efficiently. I call this explanation for the negative relationship between education and endogamy the cultural adaptability effect.

Another way in which education may decrease the likelihood of endogamy is through its effect on migration patterns. For example, by increasing the geographic scope of the labor market, education may result in out-migration from ethnic enclaves. Leaving areas with high foreign-born concentrations makes it more difficult to meet potential spouses of the same ethnicity and so, even if ethnic preferences remain constant, the probability of endogamy decreases. I call this the enclave effect.

Lastly, it has been widely shown in both the theoretical and empirical marriage literature that assortative matching on education is an important feature of marriage markets.2 This implies that even if people do not care at all for marrying within ethnicity, there could be high endogamy rates if the distributions of education vary by ethnicity. Because searching for a spouse is costly, if immigrants care both about a spouse’s ethnicity and education level, they may be willing to trade similarities in ethnicity for similarities in education. The assortative matching effect implies that the impact of education depends on the relative availability of same education and same ethnicity potential spouses residing within close geographic proximity of the spouse-searcher.

To distinguish between the cultural adaptability and assortative matching effects, the following insight is used: By the cultural adaptability effect, education decreases the probability of ethnic endogamy regardless of ethnic background. On the other hand, by the assortative matching effect, education decreases endogamy for people in low education ethnic groups but increases endogamy for people in high education ethnic groups. In a regression framework, assortative matching can thus be identified using an interaction between own education and the average education of one’s own ethnic group relative to the general population. Because ethnic and native education levels differ by location in the United States and marriage markets are surely local in nature, average education levels are computed at the county group level, the smallest level of aggregation available in the data set.3 Although it is not possible to evaluate the importance of the enclave effect using this empirical specification, I control for the enclave effect in all regressions.

The empirical work is conducted solely on male second-generation immigrants. Their marriage decisions are studied because they are less likely to suffer from language barriers and more likely to be exposed to the U.S. marriage market. Beyond these practical concerns, second-generation immigrants are an interesting demographic group in themselves because, although they are born and most likely raised in the United States, they continue to exhibit marked preferences toward spouses of their ethnicity.4

Estimates computed using 1970 U.S. Census data indicate that assortative matching on education is very important in explaining the marriage patterns of second-generation immigrants. In fact, in the baseline model, there is no evidence of the cultural adaptability effect after controlling for the enclave and assortative matching effects. Robustness tests suggest that these results are not driven by endogeneity bias.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section II discusses background literature on assortative matching in marriage markets and provides a strategy for identifying the assortative matching effect in the data. The empirical specification is also presented in this section. In Section III, a description of the sample used and descriptive statistics are provided. Results are presented in Section IV and Section V draws conclusions.

II. ASSORTATIVE MATCHING IN THE MARRIAGE MARKET

Starting with the pioneering work of Becker (1981), economists and sociologists have used economic theory to analyze who marries whom. By assuming efficiency in the marriage market, Becker predicts positive assortative matching of spouses on any quantitative trait for which the marginal productivity of the husband’s trait on household production depends positively on the wife’s trait. He cites intelligence, education, health, fecundity, religion, and ethnic origin as examples of traits for which this is likely to be the case. Lam (1988) extends Becker’s analysis to allow for gains from marriage resulting from the joint consumption, as opposed to production, of household public goods.

This paper focuses on two characteristics on which marriage market participants may want to match: ethnicity and education. Because returns from marriage can result at least partially from the joint consumption of household public goods, it is optimal for couples to sort in the marriage market according to their similar demands for these goods. Because so many goods jointly consumed in the household are related to ethnicity, it is efficient for immigrants to marry someone of the same ethnicity. Language, cuisine, holiday celebrations, and other family traditions are some examples of household public goods related to ethnicity.5 Preferences for household public goods can also be related to people’s education levels. For example, education is related to liberal sex-role attitudes (Davis and van den Oever, 1982), a desire for fewer children (Kohn, 1977), preferences over how to spend leisure time together (Robinson, 1977), and political views (Hyman and Wright, 1979). Because children, joint vacations, and political conversations can all be considered household public goods, it is also efficient for couples to sort in the marriage market according to their demands for these public goods and, consequently, to sort by education level.6

Furtado (2006) develops a simple search model from which the following strategy for differentiating the cultural adaptability effect from the assortative matching effect is derived.7 The cultural adaptability effect implies that education always decreases the probability of endogamy. By the assortative matching effect, however, the impact of education depends on how the co-ethnic education distribution compares to the general education distribution. That is, an increase in schooling will result in a decrease in endogamy if average ethnic education is less than the average education of the general population, but an increase in endogamy if average ethnic education is greater than the general average education. Thus, to differentiate the cultural adaptability effect from the assortative matching effect, the following empirical specification is used:

| (1) |

where yijk is an indicator variable equal to one if man i in ethnicity j in geographical area k is married endogamously and zero otherwise. Sijk refers to the spouse-searcher’s years of schooling, whereas is average years of schooling for people in ethnicity j residing in area k. The vector of characteristics which capture tastes for marrying within ethnicity, Xijk, includes age and non-English native language.

The strategy described earlier allows us to differentiate the cultural adaptability effect from the assortative matching effect. However, there is another mechanism through which education may impact endogamy patterns. By the enclave effect, education may result in out-migration from areas with large co-ethnic populations, for example, by widening the geographic scope of job search. To account for this, the proportion of people residing in geographical area k that are of the spouse-searcher’s ethnicity j, pjk, and its square are included in the model.8 By the enclave effect, as education increases, people tend to move out of ethnic enclaves and so the probability of meeting potential spouses of the same ethnicity decreases. The U.S. Census does not contain information about whether people grew up in ethnic enclaves and, if so, when they moved out. Thus, it is not possible to measure the enclave effect directly. However, under the assumption that after acquiring education, people move to where they are living at the time of the survey, search for a spouse, marry, and remain in roughly the same location, the ethnic group size variable will completely purge β1 and β2 of any bias resulting from the enclave effect. Admittedly, these conditions are quite strong, but biases resulting if these assumptions do not hold are not likely to be large. They will be discussed in Section IV.

III. THE DATA

A. Sample and Variables

The main analysis in this study uses the Form 2 Metro Sample of the 1970 U.S. Census as reported by the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) (Ruggles et al., 2009) in conjunction with the 1970 Fourth Count Population Summary Tape Files, SF 4. These data were used because 1970 is the most recent year Census responders were asked for information on parents’ countries of birth. Although parental birthplace information is available in recent current population survey (CPS) samples, it is not possible to obtain accurate measures of ethnic group size and average education level within small geographic areas using the small CPS samples.

I restrict the sample to native-born married males,9 ages 18–65, with two foreign-born parents. This population was chosen because, like their immigrant parents, they are likely to exhibit strong preferences for endogamy.10 However, they are less likely than immigrants to suffer from language barriers, and their exposure to U.S. marriage markets is clear. Also, because a common way immigrants become U.S. citizens is through marriage to a native, examining the decisions of second-generation immigrants, who are by birth citizens of the United States, makes motives behind interethnic marriages less ambiguous.11 To limit any bias resulting from sampling error, the analysis is limited to individuals in the 13 ethnic groups with the largest number of second-generation male immigrants. Eighty-five percent of our initial sample belonged to these groups.

Because only one percent public use microdata samples are available from the U.S. Census in 1970, it is very difficult to obtain accurate measures of the size of the ethnic group within close geographic proximity. From the Summary Tape Files, I obtain counts of the foreign and native-born (of foreign or mixed parentage) population by country of origin at the county level. Because the county group is the smallest geographical area identifiable in the microdata, I group these counties into county groups, compute the proportion of the county group population of each ethnicity, and merge these proportions with the microdata sample by ethnicity and county group. Ethnicity, in this analysis, is based on the country of birth of the person’s father because information on mother’s country of birth is suppressed in the data when both parents are foreign born. County groups, which are similar to Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs) in the 1990 and 2000 Censuses, identify metropolitan areas or county components of metropolitan areas with more than 250,000 residents. Although the appropriate level of geographic aggregation is unclear, county groups are made up of an urban center and surrounding counties where economic activity is focused at the center.12 Because the central urban area is considered to be the labor market center, it is not unreasonable to believe that it is also the marriage market center. Average characteristics computed from smaller geographical areas may not accurately depict the average characteristics of the spouse candidates that bachelors actually encounter.

A second-generation male is considered to be married endogamously if his wife has at least one parent born in the country of birth of his father. Again, only father’s country of birth is considered because mother’s country of birth is not reported when both parents are foreign born. Note that by this definition, a second-generation male will be considered ethnically intramarried if he marries an immigrant, a woman whose parents were both born abroad, or a woman with one parent born abroad, as long as the couple shares a common ethnic background.

B. Descriptive Statistics

The prevalence of endogamous marriages becomes apparent when comparing actual endogamy rates with the endogamy rates implied by random matching for each ethnic group. As seen in Table 1, for example, because Italians constitute 2.1 percent of the population of the United States, random matching within the United States would imply an endogamy rate of 2.1 percent. The actual endogamy rate of 42 percent is 20 times this amount. As discussed previously, it may not be reasonable to compare endogamy rates to the rates implied by random matching within the entire country because marriage markets do not extend to the entire country. The average Italian lives in a county group in which Italians make up 5.1 percent of the population. This still is not even close to the endogamy rate of 42 percent.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Ethnicity

| Endogamy Rate | Percentage of U.S. Sharing Ethnicity | Percentage of County Group Sharing Ethnicity | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 6.45 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 2,049 |

| Germany | 10.07 | 1.78 | 2.39 | 2,396 |

| Norway | 10.89 | 0.30 | 1.44 | 1,166 |

| Austria | 12.22 | 0.48 | 0.81 | 1,783 |

| Ireland | 13.17 | 0.71 | 1.58 | 2,248 |

| Hungary | 13.73 | 0.30 | 0.57 | 8,792 |

| Canada | 17.86 | 1.49 | 4.52 | 2,505 |

| Yugoslavia | 18.10 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 2,001 |

| Czechoslovakia | 20.94 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 3,366 |

| Poland | 31.25 | 1.17 | 2.44 | 1,683 |

| Russia | 35.45 | 0.96 | 2.21 | 5,408 |

| Italy | 42.37 | 2.09 | 5.09 | 1,260 |

| Mexico | 54.97 | 1.15 | 6.37 | 4,832 |

| Total | 27.53 | 1.18 | 2.87 | 34,489 |

In Table 2, means and standard deviations are shown for various characteristics of second-generation males by whom they marry. Men who marry within their ethnicity have on average 1 year less of schooling than their intermarrying counterparts. Their wives follow this pattern almost exactly. Also note that, as implied by the assortative matching mechanism, the difference in average years of schooling between husband and wife is greater in endogamous couples than in exogamous couples. Table 2 also shows that men who marry within their ethnicity are slightly older than those who marry out, suggesting a downward trend in ethnic endogamy through time. Almost 80% of the second-generation males in our sample do not have English as their native language. Not surprisingly, men with a non-English native language are more likely to marry within their ethnicity.13

TABLE 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Husband and Wife by Marriage Type

| Exogamous Couples

|

Endogamous Couples

|

All

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Husband | ||||||

| Schooling | 11.44 | 3.35 | 10.32 | 3.46 | 11.13 | 3.42 |

| Age | 49.17 | 9.73 | 51.04 | 8.52 | 49.68 | 9.45 |

| Non-English Native Language | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.88 | 0.32 | 0.79 | 0.41 |

| Wife | ||||||

| Schooling | 11.50 | 10.01 | 10.07 | 3.01 | 46.32 | 9.76 |

| Age | 45.63 | 2.51 | 48.15 | 8.83 | 11.11 | 2.74 |

| Non-English Native Language | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.50 |

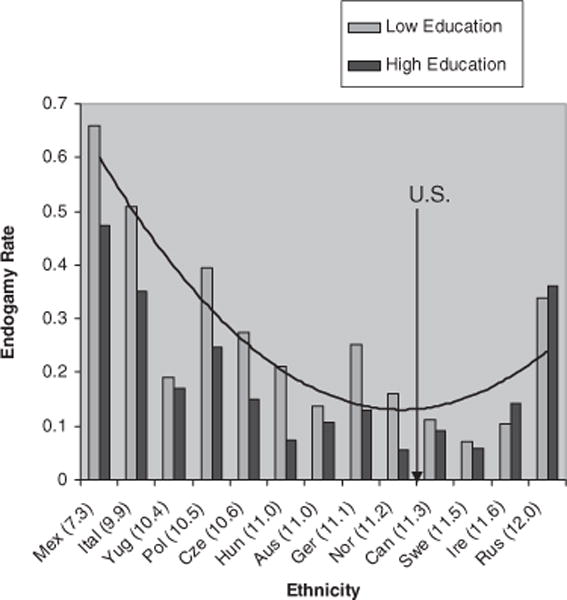

Figure 1 graphs endogamy rates by ethnicity and level of education. Ethnicities are ordered on the x-axis by average years of schooling. The darker bars show endogamy rates for people with education levels at or above the median for that ethnicity while the lighter bars show endogamy rates for people with education levels below the median. The black line marks the average years of schooling in the United States for 18- to 65-year-olds, 11.3 (Author’s own calculations using 1970 U.S. Census data). Superimposed on the bar chart is a fitted polynomial through the low education endogamy rates, and consistent with the assortative matching model, the curve has a U shape. That is, the highest endogamy rates are for people in ethnicities with average education levels furthest away from the average education in the U.S. population. Moreover, for ethnicities with average education levels less than the U.S. average, within ethnicity, highly educated people have lower endogamy rates than lowly educated people. The opposite is true for the two ethnic groups with the highest average levels of education: High-skilled Irish and Russian second-generation immigrants have higher endogamy rates than the low skilled within these ethnic groups. This certainly points to a potential role of assortative matching on education in explaining endogamy rates, but the next section explores this more formally.

FIGURE 1.

Endogamy Rates by Ethnicity and Education

Notes: Ethnicities are ordered by average years of schooling (shown in parentheses). Low education refers to people with less than the median education within the ethnic group whereas high education refers to people with the median or above the median years of schooling. A trend line is plotted for low education second-generation immigrants.

IV. RESULTS

A. Baseline Results

To disentangle the cultural adaptability effect from the assortative matching effect, I test for a differential impact of education depending on the average education in one’s ethnic group. Table 3 presents estimated coefficients from different specifications of the baseline model. Standard errors are all clustered on ethnicity-county group cells. Notice that when education and controls for preferences for marrying within ethnicity (age and non-English native language) are the only variables included on the right hand side of the regression, education has a negative and significant impact on the probability of in-marriage. Regression results suggest that one more year of education leads to a 1.5 percentage point decrease in the probability of marrying within ethnicity. Estimated coefficients on the controls for endogamy preference have the expected signs.

TABLE 3.

Effect of Schooling on Endogamy

| Endogamy | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Schooling | −0.015** (0.002) |

−0.009** (0.002) |

−0.001 (0.002) |

| Age | 0.003** (0.001) |

0.004** (0.001) |

0.005** (0.001) |

| Non-English Native Language | 0.131** (0.012) |

0.102** (0.010) |

0.093** (0.010) |

| Percentage of County Group Sharing Ethnicity | 5.790** (0.299) |

5.575** (0.319) |

|

| Percentage of County Group Sharing Ethnicity Squared | −11.860** (1.064) |

−11.792** (1.104) |

|

| Years of Schooling × (Mean Ethnic Schooling − Mean Schooling) | 0.004** (0.001) |

||

| Mean Ethnic Schooling − Mean Schooling | −0.063** (0.013) |

||

| Constant | 0.200** (0.050) |

−0.067 (0.042) |

−0.205** (0.039) |

| Observations | 39,489 | 39,489 | 39,489 |

| R-squared | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

Notes: Mean ethnic schooling refers to the average years of schooling within the person’s ethnic group living within the person’s county group. Mean schooling refers to the overall average years of schooling in the person’s county group. Standard errors are clustered on ethnicity-county group cells.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10.

When controlling for ethnic group size in specification (2), the effect of education alone (cultural adaptability effect) decreases by 40% suggesting that the enclave effect plays some role in the relationship between education and endogamy. As expected, the larger the ethnic representation in the county group in which a second-generation immigrant lives, the more likely he is to marry within his ethnicity.

The interaction between education and the difference between ethnic and overall average education levels within county groups is added in specification (3) to differentiate the assortative matching effect from the cultural adaptability effect. Consistent with the assortative matching theory, the coefficient on the interaction is positive and significant suggesting that an increase in education leads to an increase in endogamy for people surrounded by highly educated co-ethnics, but a decrease in endogamy for people surrounded by low education co-ethnics. In fact, when the interaction is added to the specification, the estimated coefficient on education alone becomes indistinguishable from zero. This is suggestive of cultural adaptability not being a strong mechanism linking education and endogamy patterns.

Specific examples are useful for interpreting the magnitude of the assortative matching effect of education. The effect of an increase in schooling has the greatest impact on second-generation immigrants in countries of origin whose mean education values are very different from the rest of the population. For example, a typical Mexican second-generation male will decrease his probability of marrying a Mexican by 1.7 percentage points, −0.001 + 0.004(7.3 – 11.3), by acquiring one additional year of education. Note that Mexicans have 7.3 years of education on average, whereas the average education in the United States in this time period and relevant age group is 11.3 (Figure 1). This suggests that his decision to finish high school leads to an 8 percentage point increase in the probability of intermarriage. On the other hand, for an average Russian second-generation immigrant, an additional year of education increases his probability of intramarriage by 0.18 percentage points, −0.001 + 0.004 (12.0 – 11.3). For the typical Russian, finishing college results in a 0.72 percentage point increase in the probability of marrying another Russian.

B. Robustness Checks

It is natural to ask whether the estimates presented in Table 3 reflect causal relationships between education and endogamy. In this section, a number of approaches are taken to address this concern.

The identification strategy discussed earlier relies on variation in average education levels across county groups and ethnic groups. There is reason to be concerned that empirical results are driven by unobservable differences in tastes for endogamy that vary by ethnicity. For example, Russians may have unobserved characteristics which result in higher endogamy rates for the high skilled and Mexicans may have characteristics which result in higher endogamy rates for the low skilled. To account for this as well as unobserved characteristics which vary by city, ethnicity and county group fixed effects are added to the specification in column 1 of Table 4. When within-ethnicity cross-county group variation becomes the source of identification, the coefficient on education alone becomes more negative and acquires statistical significance. At the same time, the education interaction coefficient becomes even larger in magnitude, and remains statistically significant. Thus, we can conclude that although support for the cultural adaptability effect depends on the source of identification, there is evidence of the assortative matching effect of education regardless of the identifying variation.

TABLE 4.

Effect of Education on Endogamy, Robustness Checks

| Endogamy | County Group 1 |

Country 2 |

State of Residence: Movers 3 |

Birth State: Movers 4 |

County Group: Non-movers 5 |

County Group: Had First Child After Age 25 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Schooling | −0.005** (0.002) |

0.002 (0.002) |

0.000 (0.002) |

0.000 (0.003) |

0.008 (0.010) |

0.002 (0.004) |

| Age | 3.997** (0.394) |

5.505** (0.300) |

7.377** (1.264) |

4.429** (1.364) |

2.885* (1.282) |

3.622** (0.481) |

| Non-English Native Language | −9.265** (1.808) |

−12.789** (1.132) |

−42.544** (11.928) |

−24.798* (11.723) |

−1.426 (3.738) |

−5.991** (1.268) |

| Percentage Sharing Ethnicity | 0.002* (0.001) |

0.009** (0.002) |

0.009** (0.001) |

0.010** (0.002) |

0.011** (0.004) |

0.007** (0.001) |

| Percentage Sharing Ethnicity Squared | −0.043** (0.014) |

−0.139** (0.020) |

−0.133** (0.013) |

−0.129** (0.019) |

−0.182** (0.055) |

−0.109** (0.020) |

| Years of Schooling × (Mean Ethnic Schooling − Mean Schooling) | 0.007** (0.000) |

0.006** (0.000) |

0.006** (0.001) |

0.006** (0.001) |

0.004* (0.002) |

0.004** (0.001) |

| Mean Ethnic Schooling − Mean Schooling | 0.062** (0.010) |

0.081** (0.011) |

0.088** (0.011) |

0.106** (0.012) |

0.048 (0.051) |

0.035 (0.024) |

| Constant | −0.456** (0.053) |

−0.287** (0.036) |

−0.250** (0.044) |

−0.232** (0.067) |

−0.313+ (0.177) |

−0.160* (0.079) |

| Ethnicity fixed effects | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| County group fixed effects | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Observations | 39,489 | 39,489 | 7,590 | 7,590 | 341 | 5,275 |

| R-squared | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.13 |

Notes: Column 1 adds ethnicity and county group fixed effects to the last specification shown in Table 3. Column 2 computes the percentage sharing ethnicity and average schooling variables at the country-wide level as opposed to the county group level. Results shown in columns 3 and 4 are for a sample of people who reside in a different state than their state of birth. The percentage sharing ethnicity and average education variables are computed at the state of residence and state of birth levels, respectively. The state of residence and state of birth regressions are run using the Form 2 State sample of the 1970 U.S. Census instead of the Metro sample in order to increase sample size. In column 5, the main specification is run on a sample of males who did not change counties within the 5 years prior to the survey but whose spouses did. In column 6, the baseline specification is run on a sample of males who had their first child (eldest child living in the household) after the age of 25. To increase the probability that the male’s first child is the eldest child living in the household, the sample consists of only males whose eldest child is younger than age 13. Standard errors are clustered on ethnicity-county group cells in columns 1, 5, and 6; on ethnicity in column 2; ethnicity-state cells in column 3; and ethnicity-state of birth cells in column 4.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10.

A potential problem with even the fixed effects specification is that spouse-searchers may choose cities in which to live based on their own education and tastes for endogamy. Surely, people with stronger preferences for endogamy are more to live in areas with a larger ethnic population and if education decreases ethnic preferences, our estimate of the cultural adaptability effect will be biased towards zero. For this reason, we can interpret the coefficient on education as the cultural adaptability effect purged of its effect through location decisions. The empirical literature suggests that education always has a nonnegative effect on out-migration, and so it is unlikely that the coefficient measuring the assortative matching effect is biased.14

It is also possible that spouse-searchers make location decisions based on the relationship between the average education of their ethnic group and the education of the general population in particular cities. If both the highly educated living in areas with other highly educated members of their ethnic groups and the lowly educated living among other lowly educated co-ethnics have strong preferences for endogamy for reasons unrelated to matching on education, then the assortative matching coefficient will be biased upward. To deal with this concern, I exploit the fact that although people can choose their city of residence, ethnic group size and average ethnic education level across the entire United States are not choice variables. Column 2 of Table 4 reports estimated coefficients for a regression where the size and average education variables are computed over the entire country. In this specification, where identification comes only from cross-ethnicity variation, the cultural adaptability coefficient is not statistically different from zero, whereas the assortative matching coefficient is positive, statistically significant, and again larger in magnitude than the baseline assortative matching coefficient. This is not my preferred specification because it does not control for the enclave effect and it is unlikely that marriage markets extend to the entire country, but it is comforting that the main conclusions are the same regardless of whether marriage markets are constructed at the county group or countrywide level.

An additional potential problem with the estimates is that the group size and average education variables are measured at the time and in the location where the survey was conducted as opposed to the time and place where these married immigrants were searching for spouses. Although age at marriage and full migration histories are not available from the Census, states of birth are known for most native-born Census-responders. Using data on people whose birth state is not the same as state of residence, I ran regressions using both state of birth and state of current residence measures of ethnic group size and average education levels.15 Because the metro sample of the 1970 Census masks state information for people living in county groups that straddle state boundaries, the Form 2 State sample is used to generate the results in columns 3 and 4 of Table 4. As can be seen in the table, regardless of whether state of birth or state of current residence is used, education alone has an insignificant effect on endogamy while the interaction between education and the relative education of the person’s ethnic group has a positive and significant effect. This suggests that the baseline results are not driven by post-marriage migration decisions.

By measuring the size and average education variables at the state-wide, country-wide, and especially state of birth levels, we are not allowing education to affect endogamy through migration across county groups. Recall that one of the ways education may affect endogamy is through its effect on migration patterns. To take another approach at addressing the endogeneity and measurement issues with the baseline model while controlling for the enclave effect, I ran the analysis on a sample of males that presumably married within the past 5 years but did not move county groups during this time. Although age at marriage is not available from the 1970 Census, residential location 5 years prior to the survey is available for both husband and wife. It may be reasonable to assume that couples in which the husband does not change counties within the previous 5 yr, but the wife does are newlyweds. As can be seen in column 5 of Table 4, even using this very small sample of a little over 300 observations, the main conclusion is the same: there is strong evidence of the assortative matching effect but no statistically significant support for the enclave effect.

City of residence is not the only choice variable in the analysis. One may also be concerned about reverse causality in that people may choose to acquire different levels of education depending on the ethnicity of their spouses. For example, Russians who happen to marry other Russians may end up acquiring more schooling post-marriage.16 To address this issue, I would have liked to run the regressions on the sample of people who married after the age of 25 and are thus unlikely to have acquired education post-marriage. Unfortunately, age at marriage is not available in the data set. However, if most people have their first child shortly after marriage, we can use age minus age of eldest child as a proxy for age at marriage. One problem with this method is that the eldest child in the household may not be the eldest child ever born to the couple. To assuage this concern, only couples whose eldest child is younger than age 13 are considered. Despite the issues with this proxy for age at marriage, column 6 of Table 4 shows that again the assortative matching coefficient is positive and statistically significant while the cultural adaptability coefficient is statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Although all of the robustness checks presented in this section are potentially problematic, they are problematic for different reasons, and so it is comforting that all specifications provide strong support for the assortative matching effect. Admittedly, the evidence is more mixed when it comes to the cultural adaptability effect. Furtado and Theodoropoulos (2009) provide an analysis comparing the cultural adaptability effect to the assortative matching effect for different populations.

V. CONCLUSION

An important channel through which intergenerational assimilation occurs, arguably the most important, is marriage to a native. This paper examines the effect of human capital on the intermarriage decisions of second-generation immigrants with two foreign-born parents.

Three avenues linking education to the likelihood of intermarriage are examined. The cultural adaptability effect suggests that educated people are better able to adapt to different customs and so are more likely to marry natives. The enclave effect suggests that educated immigrants are more likely to move out of their ethnic enclaves making them less likely to meet possible spouses of their own ethnicity and so, naturally, less likely to marry them. Lastly, the assortative matching effect stresses the importance of similarities in education with a spouse. This implies that given a costly search process, educated immigrants may be willing to substitute similarities in ethnicity for similarities in education. To differentiate the cultural adaptability effect from the assortative matching effect, I exploit the assortative matching prediction that an increase in education for immigrants surrounded by high education co-ethnics should decrease the likelihood of intermarriage while the opposite is true for people surrounded by low education co-ethnics.

Using 1970 U.S. Census data on second-generation immigrants, I find that indeed the effect of education on endogamy differs by ethnicity suggesting that assortative matching is an important driver of ethnic endogamy patterns. In fact, although there is some evidence of the enclave effect, after accounting for the assortative matching effect, the cultural adaptability theory has no support from the data in the baseline model. Second-generation immigrants do exhibit marked preferences for marrying within their ethnicity, but contrary to the predictions of the cultural adaptability effect, these preferences are not affected by education, at least not after accounting for migration patterns.

The results from this analysis can be interpreted beyond the realm of marriage decisions if interethnic marriages are viewed as a measure of the broader interaction between immigrants, of any generation, and natives. Presumably, human capital affects intermarriage in the same ways it affects any association between people of different ethnicities. If the social integration of immigrants is in fact a policy goal, the conclusions from this paper can provide some insights into both immigration and education policy. Given the correlation in education levels between parents and their offspring, the fact that education affects second-generation endogamy mainly through assortative matching has implications for which immigrant groups can most quickly assimilate into U.S. society. Specifically, it implies that those ethnic groups with average education levels closest to the U.S. level can more easily integrate into U.S. society. In fact, given the evidence that all else equal, immigrants prefer to marry within their ethnicity, it may be even more beneficial to give priority to the people with education levels most similar to U.S. average levels but that are in the least educated ethnic groups. Because of the greater scarcity of potential spouses of both the same ethnicity and education level, these immigrants would be most likely to associate with natives.17

The role of human capital in intermarriage decisions also provides an indirect avenue through which education policies could catalyze the social integration process of immigrants and their children. The fact that education works mainly through assortative matching suggests that it is the immigrants at the bottom of the education distribution that have the most to gain from education policies. For example, because education only has a positive effect on interethnic marriage rates for low education ethnicities, policies aimed at increasing high school graduation rates would be more beneficial than policies providing scholarships for graduate schools.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CPS

Current Population Survey

- IPUMS

Integrated Public Use Microdata Series

- PUMAs

Public Use Microdata Areas

Footnotes

This paper uses interethnic marriage, outmarriage, and exogamy synonymously. Same-ethnicity marriage is also referred to as intraethnic marriage and ethnic endogamy.

Trends in assortative mating on education in the latter half of the twentieth century are described and analyzed in Schwartz and Mare (2005).

As will be described in more detail later, county groups are established by the Census to correspond with labor markets, and there are reasons to believe marriage markets correspond roughly with labor markets.

Angrist (2002) exploits the high endogamy rates of second-generation immigrants to test for the importance of sex ratios on various economic and demographic outcomes.

There is evidence that interethnic marriages are more likely to end in divorce (Kalmijn, de Graaf, and Janssen, 2005). These divorces could be a result of a failure to agree on important ethnicity-specific household public goods.

Kalmijn (1993) finds that educational homogamy among second-generation immigrants has increased over the years, whereas ethnic endogamy has decreased.

In Furtado (2006), preferences for similarities in education are modeled using a quadratic loss function of the difference between spousal education levels. The same identification strategy can be derived from a model which assumes that all people prefer more education in a spouse to less but that high education spouse-searchers derive more utility from a spouse’s education than low education spouse-searchers.

The square term was included to allow for nonlinearities of the type discussed in Bisin and Verdier (2000) and Bisin, Topa, and Verdier (2004).

I have completed the same analysis on second-generation females and results were qualitatively the same.

Bleakley and Chin (2010) find that immigrants arriving at a very young age are substantially more likely to marry a native. If the foreign-born parents of children with mixed parents arrived at a very young age, it is natural that their native-born children have very weak preferences for ethnic endogamy. In fact, ethnic endogamy rates of native-born children with two foreign-born parents are more than double the rate of children with one foreign-born parent (author’s calculations). Nevertheless, I also conducted the analysis on the native born with at least one foreign-born parent and the main results were the same.

Marriage choices of immigrants have been found to depend a great deal on the type of visa they hold when entering the country (Jasso and Rosenzweig, 1990; Jasso et al., 2000). Immigrants without a valid visa upon entering the U.S. are more likely to marry a native.

Many large county groups are divided into two or more subareas.

Since children have gained more independence from parents as society has modernized in the past century (Kalmijn, 1991), parental preference for the intramarriage of their children may have become less of a salient factor in ethnic preferences of younger second-generation immigrants. Children of parents with strong ethnic attachments are more likely to have a non-English mother tongue and identify with their parents’ country of birth (Stevens and Swicegood, 1987).

I ran a specification without controlling for the size of the ethnic group variables. This did not affect the estimated assortative matching coefficient, but the cultural adaptability coefficient became more negative.

In the birth state specifications, I continue to compute average education levels in 1970 but match the averages to specific people based on birth state as opposed to state of current residence.

I am not overly concerned by the actual timing of completed schooling because presumably marriage market participants match on final education as opposed to education at the time of marriage. However, it is possible that marriage market participants adjust their desired schooling levels in response to the ethnicity of the person with whom they “randomly” fall in love for reasons unrelated to the importance of matching on education in the marriage market.

Of course, if this type of policy were implemented, then in the long run, the low education ethnic group could no longer be considered a low education group in the U.S.

References

- Angrist J. How do Sex Ratios Affect Marriage Markets and Labor Markets? Evidence from America’s Second Generation. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2002;117:997–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley H, Chin A. Age at Arrival, English Proficiency, and Social Assimilation among U.S. Immigrants. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2010;2:165–92. doi: 10.1257/app.2.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisin A, Verdier T. ‘Beyond the Melting Pot’: Cultural Transmission, Marriage, and the Evolution of Ethnic and Religious Traits. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2000;115:955–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bisin A, Topa G, Verdier T. An Empirical Analysis of Religious Homogamy and Socialization in the U.S. Journal of Political Economy. 2004;112:615–64. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. Ethnic Capital and Intergenerational Mobility. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1992;107:123–50. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. The Intergenerational Mobility of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics. 1993;11:113–35. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. Ethnicity, Neighborhoods, and Human Capital Externalities. American Economic Review. 1995;85:365–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick BR, Houseworth C. Ethnic Intermarriage Among Immigrants: Human Capital and Assortative Mating. IZA Discussion Paper No. 3740. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM. Socioeconomic Determinants of Intraethnic Marriage and Friendship. Social Forces. 1977;55:997–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, van den Oever P. Demographic Foundations of New Sex Roles. Population Development Review. 1982;8:309–40. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B, Trejo SJ. Intermarriage and the Intergenerational Transmission of Ethnic Identity and Human Capital for Mexican Americans. CReAM Discussion Paper Series 0902. 2009 doi: 10.1086/658088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado D. Human Capital and Interethnic Marriage Decisions. IZA Discussion Paper 1989. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2010.00345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado D, Theodoropoulos N. Interethnic Marriage: A Choice between Ethnic and Educational Similarities. CReAM Discussion Paper Series 716. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson A. Education and Black-White Interracial Marriage. Demography. 2006;43:673–89. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S, Saenz R, Aguirre BE. The SES Selectivity of Interracially Married Asians. International Migration Review. 1995;29:469–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman HH, Wright CR. Education’s Lasting Influence on Values. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Rosenzweig M. The New Chosen People: Immigrants in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Massey D, Rosenzweig M, Smith J. Assortative Mating Among Married New Legal Immigrants to the United States: Evidence From the New Immigrant Survey Pilot. International Migration Review. 2000;34:443–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Shifting Boundaries: Trends in Religious and Educational Homogamy. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:786–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. Spouse Selection among Children of European Immigrants: A Comparison of Marriage Cohorts in the 1960 Census. International Migration Review. 1993;27:51–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, de Graaf PM, Janssen JPG. Intermarriage and the Risk of Divorce in the Netherlands: The Effects of Differences in Religion and in Nationality. Population Studies. 2005;59:71–85. doi: 10.1080/0032472052000332719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano HH, Yeung WT, Chai L, Hatanaka H. Asian-American Interracial Marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46:179–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML. Class and Conformity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lam D. Marriage Markets and Assortative Mating with Household Public Goods: Theoretical Results and Empirical Implications. The Journal of Human Resources. 1988;23:462–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Qian Z. Measuring Marital Assimilation: Intermarriage among Natives and Immigrants. Social Science Research. 2001;30:289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberson S, Waters M. From Many Strands: Ethnic and Racial Groups in Contemporary America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Gregory RG. Intermarriage and the Economic Assimilation of Immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics. 2005;23:135–75. [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z. Breaking the Racial Barriers: Variations in Interracial Marriage between 1980 and 1990. Demography. 1997;34:263–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP. How Americans Use Their Time. New York: Praeger; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Sobek M, Alexander T, Fitch CA, Goeken R, Hall PK, King M, Ronnander C. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 4.0 [Machine-readable database] Minnesota: Population Center [producer and distributor]; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Mare RD. Trends in Educational Assortative Marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography. 2005;42(4):621–46. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, Swicegood G. The Linguistic Context of Ethnic Endogamy. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wong L. Why Do Only 5.5% of Black Men Marry White Women? International Economic Review. 2003;44:803–06. [Google Scholar]