Abstract

Policy change is recognized for underlying much of the success of tobacco control. However, there is little evidence and attention on how Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (AA and NHPI) communities may engage in policy change. Challenges for AA and NHPI communities include the racial/ethnic and geographic diversity, and tobacco data accurately representing the communities. Over the past decade, the Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy and Leadership (APPEAL) has worked to develop and implement policy change for AA and NHPI communities. This article describes APPEAL’s 4-prong policy change model, in the context of its overall strategic framework for policy change with communities that accounts for varying levels of readiness and leadership capacity, and targets four different levels of policy change (community, mainstream institution, legislative, and corporate). The health promotion implication of this framework for tobacco control policy engagement is for improving understanding of effective pathways to policy change, promoting innovative methods for policy analysis, and translating them into effective implementation and sustainability of policy initiatives. The APPEAL strategic framework can transcend into other communities and health topics that ultimately may contribute to the elimination of health disparities.

Keywords: Asian, minority health, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, tobacco prevention and control, program planning and evaluation, public health laws/policies

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco control policy change has contributed tremendously to decreasing tobacco use and represents one of public health’s top 10 achievements in the 20th century (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999). Tobacco control policy change, in particular smoke-free legislation and cigarette excise taxes, has been the single largest investment on tobacco control by the CDC and the tobacco control movement over the past 30 years. The Director of the CDC, Dr. Thomas Frieden, identified policy change along with socioeconomic factors as the two most important tiers of his five-tier health impact pyramid (Frieden, 2010).

Despite the great success of tobacco policy change, the decline in tobacco use prevalence has stalled, with still high rates particularly among marginalized communities of color (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). Still, tobacco is the single most preventable cause of death for all groups, including Asian Americans and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (AAs and NHPIs; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). The number one cancer for all AA and NHPI subgroups (except one) is lung cancer usually due to smoking (Haiman et al., 2006).

The objective of this article is to describe a 4-prong policy change model, in the context of a larger strategic framework for policy change, for AAs and NHPIs created by the Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy and Leadership (APPEAL). Through understanding the different policy levels and strategies, AAs and NHPIs can be empowered to engage in policy change for their communities.

BACKGROUND

Tobacco control policy change is important for AAs and NHPIs, but there are challenges from multiple fronts. The diverse nature of the AA and NHPI communities alone is a major challenge, consisting of individuals from over 45 different ethnicities, speaking over 100 different languages, and living in the 50 U.S. states and 6 U.S.-associated Pacific Island jurisdictions. Each community possesses unique cultures, histories, and traditions. Combined, AAs and NHPIs are one of the fastest growing ethnic/racial groups in the nation, growing by more than 30% in many states (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

Another challenge for AA and NHPI policy change is having data, disaggregated by ethnicity and gender, that accurately reflect community tobacco prevalence. AA and NHPI local, statewide, and national studies have shown that males among certain AA and NHPI ethnic subgroups have some of the highest smoking prevalence in the United States (Chae, Gavin, & Takeuchi 2006; Lew & Tanjasiri, 2003)—that is, 24.4% among Cambodian males (Friis, 2012), 24.4% to 50.8% among Vietnamese males (Tong et al., 2010), and 27.9% among Korean males (Carr, Beers, Kassebaum, & Chen 2005). Tobacco use (including chewing tobacco) is high for both NHPI males and NHPI females. For example, Guam has the second highest prevalence of tobacco use among all U.S. states and territories; this has remained unchanged since 2001. Chamorro adults, the indigenous ethnic population in Guam, smoke the most, with a prevalence of 40%.

Many AA and NHPI communities also face socioeconomic inequities that compound and magnify health disparities and create a much higher burden of disease (Commission on Social Determinants of Health, 2008). Historically, NHPIs and Southeast Asian American groups have high rates of poverty, AAs are more likely to be linguistically isolated (40% limited English proficient; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000), and AAs and NHPIs are less likely to have a usual source of care. This is compounded by the high uninsured and underinsured rates for specific AA and NHPI groups (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2008). In addition, low-income AAs and NHPIs, who vastly represent workers in the service industry, are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke.

Strategic Framework for Tobacco Policy Change

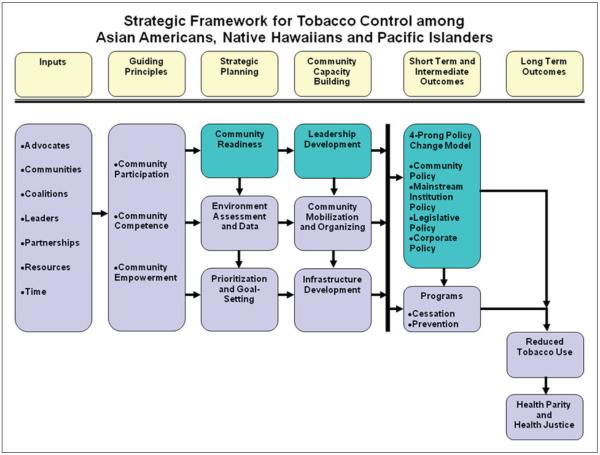

Over the past decade, APPEAL has developed and used a strategic framework for communities to address tobacco policy change (Figure 1) and ultimately help eliminate tobacco disparities (Lew, 2009). This framework consists of many elements of which three models are key for creating policy change: community readiness, leadership development, and the 4-prong policy change models. Together, these elements in combination can help AA and NHPI communities move toward successful policy change. Although we identify levels for action, educational outreach at all levels, whether with community members, decision makers, legislators, or the press, should also be recognized as important activities too. The first two models have been evaluated and tested separately and are described below.

FIGURE 1. Strategic Framework for tobacco control With Policy change Models (Highlighted in Blue).

Community Stages of Readiness Model and Other Assessments

The APPEAL community stages of readiness model provides a tool for measuring community readiness and increasing readiness levels through culturally tailored health education and communication programs (Lew, Tanjasiri, Kagawa-Singer, & Yu, 2001). Based on Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1983) transtheoretical model, the APPEAL community stages of readiness model measures progress on community interventions using a community readiness continuum (APPEAL, 2006). It provides culturally tailored methods for increasing community readiness for tobacco control and to identify appropriate-level technical assistance and training to move communities to a higher stage of readiness. A guide for conducting community needs assessment is also available (APPEAL, 2005).

Community Leadership Development Model and Capacity Building

More than 700 community leaders from AA and NHPI and other priority populations have been trained using the community-tailored APPEAL leadership model. The signature adaptation of the APPEAL leadership model has been the successful implementation of the yearlong Leadership and Advocacy Institute to Advance Minnesota’s Parity for Priority Populations (LAAMPP) in Minnesota for five priority population groups (i.e., AAs, African Americans, American Indians, Latinos, and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgenders; Lew, Martinez, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011). LAAMPP’s focus on leadership development has allowed the Fellows and their respective communities to engage in tobacco control policy and change. Leadership development and other capacity building are critical for building a foundation for AA and NHPI and other priority populations to engage in tobacco control policy change.

APPEAL 4-PRONG POLICY CHANGE MODEL

Policy change can be defined as the act of changing rules and/or regulations that govern or guide a body of people. The APPEAL 4-prong policy change model (Figure 1) uses this wider definition of policy change to include four levels: (a) the AA and NHPI communities, (b) mainstream tobacco control and health institutions, (c) legislative, and (d) corporate (Lew, 2009). This model allows for different pathways to achieve successful social norm change as opposed to solely focusing on legislative policies, which have not historically always engaged priority populations. Although legislative policy change may be the ultimate goal of some campaigns, focusing on any of the other three levels may also help communities better engage in creating social norm change, particularly in marginalized communities. The 4-prong policy change model designs its strategies based on the policy change level that is being used and recognizes that each of the four levels requires a different message, tactic, and support through technical assistance to be effective in creating policy change. At any one time, there may be activity on multiple levels of policy change.

There are inherent challenges with prioritization of the tobacco control policy change at various levels (Lew & Tanjasiri, 2003). At the AA and NHPI community level, tobacco control is not always a high priority given the multitude of health and social issues facing that particular community. At the mainstream institution level (e.g., state health departments, universities, health institutions), AAs and NHPIs and other priority populations have not been the priority. At the legislative level (e.g., state legislatures and Congress), at times, neither priority populations nor tobacco control are priorities. In contrast, at the corporate level (e.g., tobacco industry), AAs and NHPIs and other priority populations have been an important priority to target as consumers and, in the case of AAs, as retailers of their products.

Community Level

This community-level policy change refers to policy change (broadly defined) primarily within AA and NHPI communities and other priority populations and can include activities such as developing smoke-free policies in multiunit housing, at community events and through community organizations. For example, the Chinese Progressive Association in San Francisco launched a focused, culturally tailored initiative to create smoke-free policies in single residency occupancy apartment buildings where mostly low-income, and often elderly, Chinese immigrants lived. Also, a community may work on community policy changes such as refusal of tobacco industry sponsorship or organizational policies to provide incentives for employees who want to quit smoking. For example, the Pacific Island Festival Association board eliminated tobacco industry sponsorship from their events in San Diego. These community policies, which may be considered voluntary and may not provide as strong and lasting a policy as those that are legislatively mandated, may still provide a more appropriate entre into policy change particularly for immigrant communities who respond to authority differently than mainstream. Within some U.S.-associated Pacific Islands, communities may still be led and influenced by traditional leaders and may include village chiefs and elders and traditional healers. Although it may not have the Western legal impact that legislative policy has, it can greatly influence the community’s social norm regarding tobacco. For example, in 2012 the Palau Council of Chiefs signed a declaration calling for the ban of tobacco products.

Mainstream Institution Level

Historically, mainstream tobacco control organizations have not always incorporated tobacco disparity issues for AAs and NHPIs and other priority populations in their efforts. As a result, disparities have widened between those who are engaged and benefit from tobacco control and policy change and those who are still marginalized.

On the mainstream institutional level, APPEAL has led parity efforts to ensure that priority populations have access to tobacco control resources and are included in the tobacco control movement. These efforts led to the development of the independent multicultural Task Force on Advancing Parity and Leadership for Priority Populations (now known as the Parity Alliance) and the adoption of the theme of parity at the 2002 National Conference on Tobacco or Health. On the state and local levels, many AA and NHPI communities and other priority populations have worked to advance parity with mainstream tobacco control and health institutions. For example, in Washington State, the Asian Pacific Islander Coalition Against Tobacco and the Center for MultiCultural Health worked with the Washington Department of Health to advocate for providing resources to build capacity of priority populations on tobacco, resulting in a series of cross-cultural leadership institutes on tobacco. Another example of mainstream institution-level change is in Minnesota through the efforts of the LAAMPP, which trains about 30 fellows from five different priority populations. After the success of the LAAMPP, LAAMPP Fellows were given two slots to have an active role on the statewide tobacco control advisory boards working on policy change.

Legislative Level

Legislative policy change can involve the policy-making process leading to laws. APPEAL has provided technical assistance and training to communities on advocating for policy change with policy makers like state legislators, mayors, and governors. One example includes the collaboration between APPEAL and Families in Good Health on the previously mentioned community-based participatory research project exploring environmental influences of AA and NHPI youth tobacco use. The involvement of youth in this study led to them sharing the results on their community to legislators in Long Beach. Although this was only one part of a much larger advocacy campaign, the Long Beach City Council passed a bill requiring licensure of tobacco retail outlets. By being actively engaged in this policy change initiative, the AA and NHPI youth involved in this process could see that their efforts to assess community needs and using these tools to advocate for better tobacco control legislative measures could result in policy change.

Another example of APPEAL’s involvement in policy change is the capacity building and technical assistance provided to Guam’s tobacco control partners, particularly those involving Chamorro and other Pacific Islander communities. Again, this was only a part of a larger advocacy effort, but eventually, Guam passed Bill 150, which increased their tobacco tax to $3 per pack of cigarettes, now making their tobacco tax one of the highest in the United States. The lesson from APPEAL’s work was the importance of building community capacity over time to engage in policy change that could eventually result in substantive measures.

Corporate Level

The corporate level may be the hardest level to work on when it comes to tobacco control because the tobacco industry has rarely been a willing partner in effective tobacco control efforts. Specifically for the AA and NHPI communities, an analysis of internal tobacco industry documents demonstrated that targeted marketing campaigns existed for AA and NHPI communities, including Philip Morris’ strategic marketing approaches called “Push,” “Pull,” and “Corporate Goodwill” (Muggli, Pollay, Lew, & Joseph, 2002). For example, the “Push” strategy recognized the high numbers of Asian retailers and their role in promoting tobacco products.

The Master Settlement Agreement in 1998 between the tobacco industry and 46 State Attorneys General is an example of a corporate-level policy change. Although the overall impact of the Master Settlement Agreement is debatable (with many states diverting funds away from tobacco control), it did result in the creation of the American Legacy Foundation, which developed the highly acclaimed Truth Campaign ads targeting youth.

Although partnering with the tobacco industry on tobacco control is not feasible or effective, APPEAL and affiliates have led campaigns using media advocacy to hold the tobacco industry accountable for marketing campaigns such as the Virginia Slims campaign, which targeted women and girls from communities of color

Lessons Learned From Strategic Framework

In summary, there are four lessons learned from the use of the 4-prong policy change model, with the foundation laid by the community stages of readiness and leadership development models (the first two models of the strategic framework):

AA and NHPI communities may require different pathways to be engaged in tobacco control policy change given the historical and cultural challenges.

Although the legislative level of policy change may be the ultimate goal, engaging in voluntary policy or community policy may provide an entre into policy change and impact on AA and NHPI community norm change.

Conducting community readiness levels may better prepare the appropriate level of technical assistance provided to effectively engage communities in policy change.

Capacity building, and particularly leadership development, is key for communities of color to engage in policy change.

These lessons are the critical components for launching a comprehensive tobacco control policy change initiative that fully engages the AA and NHPI and other communities of color.

DISCUSSION

This article describes APPEAL’s strategic framework for policy change that shows how AA and NHPI communities can engage in tobacco-related policy change. It acknowledges that communities are at different stages of readiness to engage in policy change. It shows where APPEAL tools are available to build capacity from community needs assessments to leadership training to action at one of the four policy levels. It has a broader definition of tobacco control policy, beyond legislative policy, to reflect where communities and policy intersect.

Policy analysis may benefit from this strategic framework by demonstrating how the contributions and perspectives of diverse communities may be better integrated than ignored. Focusing on the process and not just end-stage outcomes may capture better the different levels of community engagement. There is a great need to describe the successes, challenges, and key factors in policy change for AA and NHPI communities. The visibility created and lessons learned can empower other communities to follow.

Although this is based on the experience of the AA and NHPI communities at the local and national levels, more studies are needed to definitively test the overall effectiveness of the 4-prong policy change model. Policy interventions may benefit from this strategic framework by understanding how to include diverse communities in the planning as well as the intervention stage. This includes understanding the community’s needs and readiness for policy change, empowering the community with tools for leadership and technical assistance, and targeting the policy level where the community can act. The time invested in building community capacity and relationships will better serve the outcome with improved sustainability and effect, from implementation to enforcement. Combining policy change with another aspect of AA and NHPI tobacco control, such as with culturally and linguistically tailored community programs, can result in a greater decrease of smoking prevalence (Shelley et al., 2008; Tong, Nguyen, Vittinghoff, & Pérez-Stable, 2008). Although communities may need to initially focus on individual behavioral change (e.g., education at health fairs) on health issues like tobacco, public health efforts should strive toward creating policy- or systems-level change. Policy-level change ultimately has greater impact on a larger part of the community and usually is more sustainable and cost-effective over time.

Certain tobacco control policy issues are important for AA and NHPI communities but may be less visible than familiar issues (i.e., taxes or clean indoor air policies), such as youth smoking access and menthol cigarettes. The most recent national study of youth (the 2000 National Youth Tobacco Survey) indicates that by high school, 33% of AA and 32% of NHPI youth are smokers (Appleyard, Messeri, & Haviland, 2001). Studies have shown the relationship between low-income AA and NHPI neighborhoods and close proximity to a pro-tobacco (or tobacco-supportive) environment (Bader, 1993; Tanjasiri, Lew, Kuratani, Wong, & Fu, 2011). For menthol cigarettes, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2004-2008, 53.2% of smokers who were NHPI smoked mentholated cigarettes, second highest among all groups (Maryland Tobacco Control Evaluation Program, 2006). In addition, 31.2 % of smokers who were AA also smoke mentholated cigarettes.

Tobacco control policy change does not always happen equally across to all populations or even within populations. There has been expanding literature focused on the unintended consequences of tobacco control policy particularly on low-income women (Greaves & Hemsing, 2009; Moore, McLellan, Tauras, & Fagan, 2009) and communities of color including those from the AA community. Tong, Tang, Tsoh, Wong, and Chen (2009) showed that for some AA populations, there has been a disparity in smoke-free policy enforcement by educational status: lower educated women reported greater exposure to secondhand smoke at home and work than higher educated women, despite having similar knowledge levels and rules. Hawkins, Chandra, and Berkman (2012) showed that cigarette taxes were associated with reductions in household tobacco use only for parents of White children. Furthermore, tobacco control policies may have differential impact on immigrant communities, with one study suggesting that Korean American current smokers either had difficulty understanding smoking restrictions (recent immigrants) or opposed price increases (longtime residents; Kim & Nam, 2005).

The APPEAL strategic framework can engage other priority populations and health topics beyond AA and NHPI with tobacco control. As described above, APPEAL has already successfully engaged with other priority populations on tobacco control, from leadership capacity building to technical assistance. APPEAL is also utilizing this framework for other health topics, such as obesity control by moving AA and NHPI communities toward healthy eating and active living. The long-term investment into communities can strengthen the public health infrastructure.

CONCLUSION

The health promotion policy implication of this article for the AA and NHPI community on tobacco control policy engagement is for improving understanding of effective pathways to policy change, promoting innovative methods for policy analysis, and translating them into effective implementation and sustainability of policy initiatives. APPEAL’s strategic framework for policy change identifies the components and tools for communities to engage in policy change. Through understanding the policy-making process demonstrated by the 4-prong policy change model, communities may more effectively determine their level of engagement. The APPEAL strategic framework can transcend into other communities and health topics that ultimately may contribute to the elimination of health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and ClearWay Minnesota, the American Cancer Society RSGT-10-114-01-CPPB, National Cancer Institute Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (U54CA153499), and National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (1-TW-02-005).

Footnotes

Supplement Note: This article is published in the supplement “Promising Practices to Eliminate Tobacco Disparities Among Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities,” which was supported by the Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy and Leadership (APPEAL) through CDC Cooperative Agreement 5U58DP001520.

REFERENCES

- Appleyard J, Messeri P, Haviland ML. Smoking among Asian American and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander youth: Data from the 2000 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 2001;9:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy and Leadership . Conducting needs assessments for tobacco control in Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. Author; Oakland, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy and Leadership . Implementing a community readiness approach to tobacco control. Author; Oakland, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bader K. San Francisco billboard survey: Race, tobacco, and alcohol. California Rural Legal Assistance; San Francisco: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carr K, Beers M, Kassebaum T, Chen MS., Jr. California Korean American Tobacco Use Survey-2004. California Department of Health Services; Sacramento: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: Tobacco use—United States, 1900-1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1999;48(43):986–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Gavin AR, Takeuchi DT. Smoking prevalence among Asian Americans: Findings from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) Public Health Reports. 2006;121:755–763. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: The health impact pyramid. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friis RH. Socioepidemiology of cigarette smoking among Cambodian Americans in Long Beach, California. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012;14:272–280. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves LJ, Hemsing NJ. Sex, gender, and second-hand smoke policies: Implications for disadvantaged women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(2 Suppl.):S131–S137. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.012. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Le Marchand L. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins SS, Chandra A, Berkman L. The impact of tobacco control policies on disparities in children’s second-hand smoke exposure: A comparison of methods. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;16(Suppl. 1):S70–S77. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0996-9. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-0996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Race, ethnicity, & health care: Health coverage and access to care among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/7745.pdf.

- Kim SS, Nam KA. Korean male smokers’ perceptions of tobacco control policies in the United States. Public Health Nursing. 2005;22:221–229. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220305.x. doi:10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew R. Addressing the impact of tobacco on Asian Americans: A model for change. In: Bateman W, Abesamis N, Ho-Asjoe H, editors. Praeger handbook of Asian American health: Taking notice and taking action. ABC-CLIO; Santa Barbara, CA: 2009. pp. 729–750. [Google Scholar]

- Lew R, Martinez J, Soto C, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Training leaders from priority populations to implement social norm changes in tobacco control: Lessons from the LAAMPP Institute. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12(6 Suppl. 2):195S–198S. doi: 10.1177/1524839911419296. doi:10.1177/1524839911419296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew R, Tanjasiri SP. Slowing the epidemic of tobacco use among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:764–768. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew R, Tanjasiri SP, Kagawa-Singer M, Yu JH. Using a stages of readiness model to address community capacity on tobacco control in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. Asian American and Pacific Islander Journal of Health. 2001;9:66–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Tobacco Control Evaluation Program . Use of menthol cigarettes in Maryland. University of Maryland School of Public Health; College Park: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RS, McLellan DL, Tauras JA, Fagan P. Securing the health of disadvantaged women: A critical investigation of tobacco-control policy effects on women worldwide. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(2 Suppl.):S117–S120. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.015. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggli ME, Pollay RW, Lew R, Joseph AM. Targeting of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders by the tobacco industry: Results from the Minnesota Tobacco Document Depository. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:201–209. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J, DiClemente C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley D, Fahs M, Yerneni R, Das D, Nguyen N, Hung D, Cummings KM. Effectiveness of tobacco control among Chinese Americans: A comparative analysis of policy approaches versus community-based programs. Preventive Medicine. 2008;47:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.009. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjasiri SP, Lew R, Kuratani DG, Wong M, Fu L. Using Photovoice to assess and promote environmental approaches to tobacco control in AAPI communities. Health Promotion Practice. 2011;12:654–665. doi: 10.1177/1524839910369987. doi:10.1177/1524839910369987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, Tsoh J, Modayil M, Wong C, McPhee S. Smoking prevalence and factors associated with smoking status among Vietnamese in California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:613–621. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq056. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Nguyen TT, Vittinghoff E, Pérez-Stable EJ. Smoking behaviors among immigrant Asian Americans: Rules for smoke-free homes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.024. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Tang H, Tsoh J, Wong C, Chen MS. Smoke-free policies among Asian-American women: Comparisons by education status. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(2 Suppl.):S144–S150. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.001. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Census 2000. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A report of the surgeon general. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank The economics costs of non-communicable diseases in the Pacific Islands. 2012 Nov; Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/the-economic-costs-of-noncommunicable-diseases-in-the-pacific-islands.pdf.