Abstract

Background

Some evidence suggests that perinatal exposure to zidovudine may cause cardiac abnormalities in infants. We prospectively studied left ventricular structure and function in infants born to mothers infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in order to determine whether there was evidence of zidovudine cardiac toxicity after perinatal exposure.

Methods

We followed a group of infants born to HIV-infected women from birth to five years of age with echocardiographic studies every four to six months. Serial echocardiograms were obtained for 382 infants without HIV infection (36 with zidovudine exposure) and 58 HIV-infected infants (12 with zidovudine exposure). Repeated-measures analysis was used to examine four measures of left ventricular structure and function during the first 14 months of life in relation to zidovudine exposure.

Results

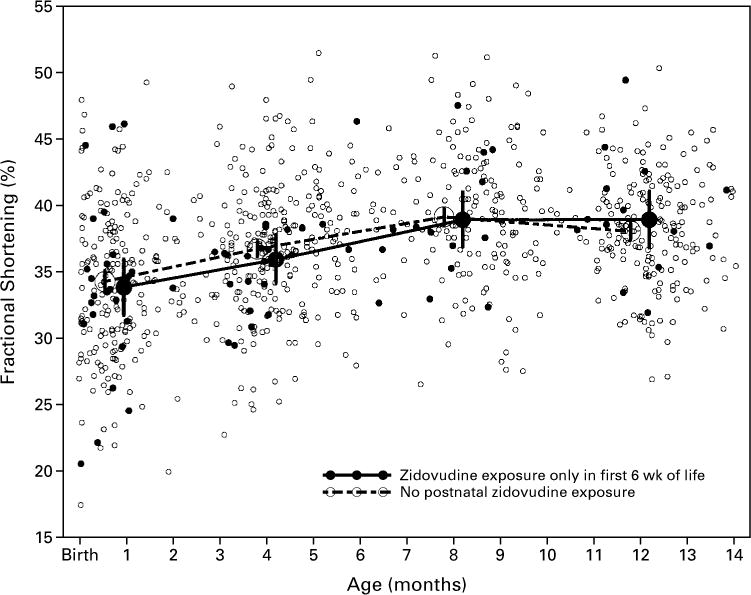

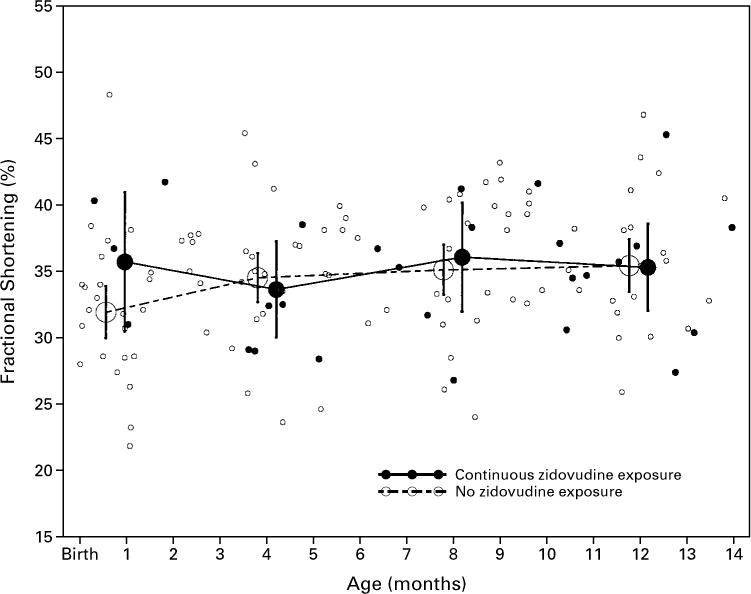

Zidovudine exposure was not associated with significant abnormalities in mean left ventricular fractional shortening, end-diastolic dimension, contractility, or mass in either non–HIV-infected or HIV-infected infants. Among infants without HIV infection, the mean fractional shortening at 10 to 14 months was 38.1 percent for those never exposed to zidovudine and 39.0 percent for those exposed to zidovudine (mean difference, −0.9 percentage point; 95 percent confidence interval, −3.1 to 1.3 percentage points; P=0.43). Among HIV-infected infants, the mean fractional shortening at 10 to 14 months was similar in those never exposed to zidovudine (35.4 percent) and those exposed to the drug (35.3 percent) (mean difference, 0.1 percentage point; 95 percent confidence interval, −3.7 to 3.9 percentage points; P=0.95). Zidovudine exposure was not significantly related to depressed fractional shortening (shortening of 25 percent or less) during the first 14 months of life. No child over the age of 10 months had depressed fractional shortening.

Conclusions

Zidovudine was not associated with acute or chronic abnormalities in left ventricular structure or function in infants exposed to the drug in the perinatal period.

Concern that zidovudine may be associated with cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction has been aroused by several studies in animals and by limited clinical data. In studies in monkeys, zidovudine at 21 percent and 86 percent of the human daily dose was administered to females in the second half of pregnancy, and the effects on fetal cardiomyocytes were observed. The cardiomyocytes were found to have abnormal and disrupted sarcomeres with myofibrillar loss; dose-related abnormalities of mitochondrial structure and function were also found. These changes were consistent with the presence of zidovudine-induced mitochondrial cardiomyopathy in fetal monkeys.1–3

Zidovudine has toxic effects on cardiac mitochondria in animals and adult humans.4 In addition, zidovudine and its metabolites can cross the placenta and have been found in the fetal heart in animals.5,6 A recent report suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction in 8 of 1754 children, including 1 child with symptomatic hypokinetic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, may have been caused by zidovudine alone or in combination with lamivudine.7 These children were exposed to the drug or drugs both in utero and after birth. Cardiomyopathy in children can be associated with mitochondrial deletions or mutations or abnormal mitochondrial-enzyme function.8,9 At least one study10 found evidence to suggest that zidovudine may cause cardiomyopathy in children, and the investigators recommended withholding zidovudine from patients with left ventricular dysfunction.

Other studies, however, have not found detrimental clinical effects on the heart. Studies of ventricular dysfunction conducted by members of our group11 and others12 have found no evidence of zidovudine-related cardiomyopathy in children. Studies in adults have not found effects of zidovudine on left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, mass, or fractional shortening.13 Similarly, administration of zidovudine to pregnant baboons did not affect the fetal heart rate or the variability of the rate.14 Short-term and long-term follow-up of uninfected children born to women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has not identified detrimental effects of perinatal zidovudine exposure or clinically important cardiovascular disease.15,16

The progressively more severe manifestations of drug-induced mitochondrial damage in cardiomyocytes are cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, and death due to pump failure, or sudden cardiac death. On echocardiographic evaluation, infants with mitochondrial cardiomyopathy frequently have reduced left ventricular contractility, depressed left ventricular systolic performance as indicated by fractional shortening, left ventricular dilatation, and increased left ventricular mass.17 Whereas children with HIV infection have a two-year cumulative incidence of chronic congestive heart failure of 5.1 percent, subclinical echocardiographic abnormalities of left ventricular structure and function are found in more than 90 percent of serially monitored HIV-infected children.18–20 These abnormalities are independent risk factors for death in HIV-infected children.21 Subclinical manifestations of cardiac toxicity and cardiomyopathy, indicated by abnormalities in left ventricular structure and function, were used as surrogates for adverse outcomes in this study.21

We used longitudinal assessment by means of sensitive noninvasive echocardiographic measurements to compare four measures of left ventricular structure and function during the first year of life between infants exposed to zidovudine and those not so exposed. Our objective was to assess whether zidovudine has acute or chronic effects on left ventricular structure and function.

METHODS

Study Design

The Pediatric Pulmonary and Cardiac Complications of Vertically Transmitted HIV Infection Study was a large, prospective, longitudinal study designed to monitor heart disease and the progression of cardiac abnormalities in children born to HIV-infected women.19,20,22 The current study was limited to the cohort of the 611 infants enrolled during fetal life (443 infants) or after delivery but before 28 days of age (168 infants). Eleven of these infants were stillborn and 600 were born alive; of those born alive, 93 were subsequently found to have HIV infection, 463 were found not to have HIV infection, and 44 were of unknown HIV status. The HIV status of the 600 live-born infants was unknown at enrollment.

Cultures for HIV were performed for the infants at birth and at three and six months of age. HIV infection was diagnosed if an infant had two cultures that were positive for HIV, had a positive test for HIV antibodies at 15 or more months of age, died of an HIV-associated condition, or had the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Infants with two negative cultures for HIV (at least one at 5 or more months of age) or negative results on serologic tests for HIV at 15 or more months of age were considered to be uninfected with HIV. The status of all others was considered to be indeterminate with respect to HIV. The cohort included in the current analysis entered the study between May 1990 and January 1994 and were followed through January 1997.

The study subjects were treated at five major clinical centers in different parts of the United States. Multiple cardiac and pulmonary tests were performed, and antiretroviral and antimicrobial therapies (e.g., intravenous immune globulin) were administered as clinically warranted. The original study protocol was not designed to gather complete data about antiretroviral therapy. We began collecting postnatal data on the infants prospectively in 1994. Data were retrospectively retrieved for patients enrolled before 1994. Data on whether the mothers had used zidovudine during pregnancy were collected prospectively throughout the study by reviewing medical records. Data on the length of in utero exposure to zidovudine were later collected retrospectively. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the infants.

According to the protocol, all children underwent echocardiographic testing at four-to-six-month intervals, regardless of their clinical status. For each echocardiographic study, sedation was used as necessary, primarily in children less than three years of age. Two-dimensional echocardiography and Doppler studies with stress–velocity analysis of left ventricular contractility19 were performed for each child. All echocardiograms were examined at a central laboratory by technicians unaware of the child’s clinical status or medications. Measurements of left ventricular end-diastolic dimension and fractional shortening were excluded from the analysis if wallmotion abnormalities or septal-motion abnormalities were identified. Data on left ventricular function in three children with congenital heart abnormalities were also excluded.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated-measures analyses were performed separately for HIV-infected infants and for those without HIV infection. For each measurement of left ventricular function, data from birth to 14 months of age were used. For each left ventricular outcome, we fitted a linear model using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation and either an unstructured variance–covariance form or a heterogeneous compound symmetry form among repeated measurements. This method allowed us to make separate estimates of the mean according to the presence or absence of postpartum zidovudine exposure and according to age (birth to 1.5 months, >1.5 to 6 months, >6 to 10 months, and >10 to 14 months). The analyses of left ventricular end-diastolic dimension and mass were also adjusted for body-surface area. For each age category, the adjusted mean for a subgroup (exposed or not exposed to zidovudine) was defined as the mean response obtained by evaluating the statistical model at the mean body-surface area of the two subgroups. The results were summarized with adjusted means and 95 percent confidence intervals. The proportions of infants with and without zidovudine exposure in the first six weeks of life who had depressed fractional shortening (shortening of 25 percent or less) were analyzed separately for HIV-infected and non–HIV-infected infants by Fisher’s exact test. The reported P values are two-sided, and a P value of 0.05 or less was considered to indicate statistical significance.

More complete longitudinal data on children without HIV infection were available for the first 14 months of life than for the period from 14 months to 5 years, for two reasons. First, as would be expected, loss to follow-up was high for non–HIV-infected children. Second, approximately half the children without HIV infection were randomly selected to remain in the study as a control group, and the remainder were randomly selected to leave the study.22 Regardless of the children’s HIV status, approximately 55 to 60 percent of all possible echocardiograms obtained during the first 14 months of life were available for analysis. Approximately 22 percent of the scheduled echocardiograms were not obtained because of missed visits. Fewer than 10 percent of the HIV-infected children were lost to follow-up by 14 months of age.22 We conducted separate qualitative analyses of the data obtained between 14 months and 5 years, using all available echocardiograms, but we do not report P values, because of the scientific rigor they imply.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the infected and uninfected infants are shown in Table 1. Most were black (51.6 percent) or Hispanic (31.4 percent); 52.3 percent were male.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 556 Infants with Known HIV Status Born Alive to HIV-Infected Women.*

| Characteristic | HIV-Infected Infants (N=93) |

Non–HIV-Infected Infants (N=463) |

|---|---|---|

| number (percent) | ||

| Lost to follow-up | 15 (16.1) | 156 (33.7) |

| Exposed to zidovudine in utero† | 27 (30.0) | 158 (35.5) |

| Zidovudine use according to ACTG 076 protocol | 3 (3.2) | 29 (6.3) |

| Postnatal medications from 0 to 14 mo | ||

| Continuous zidovudine use | 12 (12.9) | NA |

| No zidovudine use | 50 (53.8) | NA |

| Zidovudine up to 6 wk | NA | 41 (8.9) |

| No medications | NA | 380 (82.1) |

| Zidovudine sometimes | 31 (33.3) | 0 |

| Data not available | 0 | 42 (9.1) |

| No. of echocardiograms up to 14 mo‡ | ||

| 0 | 4 (6.5) | 39 (9.3) |

| 1 | 17 (27.4) | 72 (17.1) |

| 2 | 16 (25.8) | 162 (38.5) |

| 3 | 17 (27.4) | 106 (25.2) |

| 4 | 8 (12.9) | 42 (10.0) |

| Died§ | ||

| 0–14 mo | 4 (6.9) | 0 |

| >14 mo to 5 yr | 9 (15.5) | 1 (0.2) |

ACTG denotes AIDS Clinical Trials Group, and NA not applicable.

Percentages are based on 90 HIV-infected infants and 445 non–HIV-infected infants for whom data on in utero zidovudine exposure were available.

Percentages are based on the 62 HIV-infected infants who were continuously exposed to zidovudine postnatally or who were never exposed and on the 421 non–HIV-infected infants who were never exposed to zidovudine postnatally or who were only exposed up to six weeks of age.

Percentages are based on 58 HIV-infected infants and 382 non–HIV-infected infants who had at least one echocardiogram.

Of the 93 HIV-infected infants, 35 were not included in the 14-month analyses. Twelve of the remaining 58 were exposed to zidovudine at the time every echocardiogram was obtained during the first 14 months of life. The remaining 46 infants did not receive zidovudine before any of the echocardiographic studies performed in the first 14 months of life. Of the 35 infants not included in the analysis, 31 received zidovudine at some point but not throughout the initial 14 months, and 4 did not undergo echocardiographic measurements of systolic function. None of the 58 infants included in the analysis had congestive heart failure at the initial cardiac evaluation or during follow-up.

Of the 463 non–HIV-infected infants, 382 were included in the analysis at 14 months. Of the 81 infants not included in the analysis, no echocardiographic data before 14 months of age were available for 39 and no data on zidovudine exposure were available for 42. Thirty-six of the 382 infants included were given zidovudine after birth, before their uninfected status was confirmed, and 346 were not given zidovudine after birth. The median length of postnatal zidovudine treatment for 35 of the 36 infants was 42 days (range, 35 to 48). Data on length of treatment were not available for the remaining infant. All 36 were also exposed to zidovudine in utero. The median length of prenatal exposure for 33 of the 36 fetuses was 66 days (range, 8 to 273).

None of the 382 non–HIV-infected infants included in our study had congestive heart failure at enrollment or during follow-up.

Other Therapy

Among the 382 non–HIV-infected infants, none received therapies for HIV infection other than zidovudine. Forty of the 58 HIV-infected infants received one or more therapies for HIV infection other than zidovudine during the first 14 months of follow-up (Table 2). The most common were didanosine and intravenous immune globulin. Because of the number of different therapies and the sporadic nature of their use, we did not adjust for the use of other therapies in the analyses.

Table 2.

Treatments for HIV Infection Other Than Zidovudine Administered to 58 HIV-Infected Infants, According to Zidovudine Exposure up to 14 Months of Age.

| Therapy | No Zidovudine Exposure (N=46)* |

Continuous Zidovudine Exposure (N=12)† |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| any use | age at first use | median duration of therapy | any use | age at first use | median duration of therapy | |||||

|

≤1 mo |

>1–14 mo |

>14 mo |

≤1 mo |

>1–14 mo |

>14 mo |

|||||

| number | mo | number | mo | |||||||

| Didanosine | 29 | 0 | 12 | 17 | 16.5 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 15.7 |

| Zalcitabine | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Lamivudine | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 5.2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10.6 |

| Interferon | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Nevirapine | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Stavudine | 12 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 14.9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Intravenous immune globulin | 10 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 4.5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 9.9 |

| Any antiretroviral drug | 42 | 0 | 28 | 14 | 34.9 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 40.8 |

Thirty-one children received zidovudine before the age of five years (median duration of therapy, 16.2 months).

The median duration of zidovudine therapy was 27.2 months.

Initial Measures of Left Ventricular Structure and Function

The median length of in utero exposure to zidovudine was 103 days (data on length of exposure were available for 85 of 107 fetuses with any exposure [79 percent]). The infants who were found after birth not to have HIV infection had a median length of in utero exposure to zidovudine of 105 days; those who were found after birth to be infected with HIV were exposed to zidovudine in utero for a median of 68 days. Among the infants for whom a first echocardiogram was available that was obtained between birth and three months of age, in utero zidovudine exposure had no significant effect on any of the four measures of left ventricular structure or function (Table 3).

Table 3.

Initial Echocardiographic Measures According to HIV Status and Exposure to Zidovudine in Utero.*

| Measure | Zidovudine Exposure | HIV-Infected Infants† | Non–HIV-Infected Infants‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of infants | mean ±SD | P value | no. of infants | mean ±SD | P value | ||

| Fractional shortening | Yes | 16 | 34.1±3.7 | 0.87 | 91 | 34.4±6.2 | 0.86 |

| (%) | No | 40 | 34.3±5.8 | 162 | 34.5±4.9 | ||

| Contractility | Yes | 15 | −0.53±1.04 | 0.80 | 84 | −0.66±1.73 | 0.68 |

| No | 39 | −0.63±1.71 | 156 | −0.75±1.44 | |||

| End-diastolic dimension (cm) | Yes | 16 | 1.99±0.30 | 0.70 | 91 | 1.90±0.25 | 0.47 |

| No | 40 | 1.96±0.24 | 162 | 1.92±0.23 | |||

| Left ventricular mass (g) | Yes | 16 | 14.6±6.0 | 0.25 | 88 | 13.1±4.0 | 0.98 |

| No | 40 | 12.7±3.5 | 159 | 13.1±3.7 | |||

The P values are for the comparisons between zidovudine-exposed and unexposed infants, by two-sample t-test.

Among HIV-infected infants, the median age at the first echocardiogram was 38 days for those exposed to zidovudine in utero and 29 days for those not exposed.

Among non–HIV-infected infants, the median age at first echocardiogram was 21 days for those exposed to zidovudine in utero and 25 days for those not exposed.

Longitudinal Measures of Left Ventricular Structure and Function

Zidovudine had no significant effect on mean left ventricular fractional shortening, contractility, end-diastolic dimension, or mass in the first 14 months after birth in either HIV-infected or non–HIV-infected infants after adjustment for age and body-surface area (Table 4). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the similarity of the changes in infants exposed to zidovudine and those not exposed (additional data are available elsewhere*). At 10 to 14 months of age, the mean difference in fractional shortening between non–HIV-infected infants never exposed to zidovudine and non–HIV-infected infants exposed to zidovudine in utero or up to six weeks after birth was −0.9 percentage point (95 percent confidence interval, −3.1 to 1.3 percentage points; P=0.43). For HIV-infected infants, the mean difference in fractional shortening at 10 to 14 months between those never exposed to zidovudine in the first year of life and those exposed throughout the year was also small (mean difference, 0.1 percentage point; 95 percent confidence interval, −3.7 to 3.9 percentage points; P=0.95).

Table 4.

Echocardiographic Measures According to HIV Status and Zidovudine Exposure from Birth to 14 Months of Age.*

| Measure and Age (MO) | HIV-Infected Infants | Non–HIV-Infected Infants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no zidovudine exposure (n = 46) |

continuous zidovudine exposure (n=12) |

P value† | no zidovudine exposure (n=346) |

zidovudine only up to six weeks (n=36) |

P value† | |||||||

| no. | mean (95% CI) | no. | mean (95% CI) | zidovudine | zidovudine by age | no. | mean (95% CI) | no. | mean (95% CI) | zidovudine | zidovudine by age | |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.65 | ||||||||

| 0–1.5 | 22 | 31.9 (30.0 to 33.9) | 3 | 35.7 (30.5 to 40.9) | 170 | 34.3 (33.5 to 35.1) | 25 | 33.9 (31.8 to 35.9) | ||||

| >1.5–6 | 33 | 34.5 (32.7 to 36.3) | 7 | 33.6 (30.0 to 37.2) | 283 | 36.7 (36.2 to 37.3) | 25 | 36.0 (34.2 to 37.7) | ||||

| >6–10 | 28 | 35.1 (33.3 to 37.0) | 7 | 36.1 (32.0 to 40.2) | 157 | 39.2 (38.5 to 39.8) | 15 | 39.0 (36.9 to 41.0) | ||||

| >10–14 | 22 | 35.4 (33.5 to 37.4) | 10 | 35.3 (32.1 to 38.6) | 193 | 38.1 (37.5 to 38.7) | 14 | 39.0 (36.9 to 41.1) | ||||

| Contractility | 0.43 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 0.58 | ||||||||

| 0–1.5 | 22 | −0.87 (−1.59 to −0.16) | 3 | 0.14 (−1.78 to 2.06) | 163 | −0.81 (−1.03 to −0.58) | 23 | −0.31 (−0.92 to 0.30) | ||||

| >1.5–6 | 31 | −0.99 (−1.50 to −0.49) | 7 | −0.81 (−1.99 to 0.37) | 275 | −0.71 (−0.87 to −0.55) | 23 | −0.63 (−1.15 to −0.10) | ||||

| >6–10 | 28 | −1.24 (−1.74 to −0.74) | 6 | −1.14 (−2.18 to −0.09) | 148 | −0.58 (−0.77 to −0.39) | 15 | −0.63 (−1.23 to −0.04) | ||||

| >10–14 | 21 | −1.41 (−1.89 to −0.93) | 10 | −1.34 (−2.18 to −0.50) | 191 | −1.02 (−1.18 to −0.85) | 14 | −1.02 (−1.63 to −0.40) | ||||

| BSA-adjusted end-diastolic dimension (cm) | 0.12 | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| 0–1.5 | 22 | 1.94 (1.87 to 2.01) | 3 | 1.90 (1.71 to 2.10) | 169 | 1.86 (1.83 to 1.88) | 25 | 1.92 (1.84 to 1.99) | ||||

| >1.5–6 | 33 | 2.30 (2.23 to 2.36) | 7 | 2.45 (2.32 to 2.58) | 281 | 2.26 (2.24 to 2.28) | 24 | 2.28 (2.22 to 2.35) | ||||

| >6–10 | 27 | 2.53 (2.46 to 2.60) | 7 | 2.63 (2.48 to 2.77) | 155 | 2.50 (2.47 to 2.53) | 15 | 2.47 (2.39 to 2.56) | ||||

| >10–14 | 21 | 2.69 (2.61 to 2.77) | 10 | 2.63 (2.71 to 2.95) | 190 | 2.64 (2.62 to 2.67) | 14 | 2.66 (2.56 to 2.75) | ||||

| BSA-adjusted left ventricular mass (g) | 0.27 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| 0–1.5 | 22 | 11.9 (10.1 to 13.6) | 3 | 12.1 (7.4 to 16.8) | 165 | 12.3 (11.7 to 12.8) | 25 | 13.0 (11.6 to 14.5) | ||||

| >1.5–6 | 33 | 20.1 (18.5 to 21.7) | 7 | 21.6 (18.4 to 24.8) | 279 | 19.6 (19.1 to 20.0) | 24 | 18.7 (17.2 to 20.2) | ||||

| >6–10 | 27 | 25.3 (23.5 to 27.0) | 7 | 27.1 (23.7 to 30.6) | 151 | 23.9 (23.3 to 24.6) | 15 | 22.4 (20.3 to 24.4) | ||||

| >10–14 | 21 | 28.3 (26.6 to 30.1) | 10 | 30.3 (27.2 to 33.3) | 190 | 27.4 (26.8 to 28.0) | 14 | 28.9 (26.6 to 31.2) | ||||

CI denotes confidence interval, and BSA body-surface area.

The P value for zidovudine indicates whether differences between means due to postnatal zidovudine exposure were detected. The P value for the statistical interaction of zidovudine with age indicates whether age-related changes were similar for infants exposed and not exposed to zidovudine postnatally.

Figure 1.

Left Ventricular Fractional Shortening during the First 14 Months of Life in 382 Infants without HIV Infection, According to Zidovudine Exposure.

The vertical bars indicate the 95 percent confidence intervals for the means.

Figure 2.

Left Ventricular Fractional Shortening during the First 14 Months of Life in 58 Infants with HIV Infection, According to Zidovudine Exposure.

The vertical bars indicate the 95 percent confidence intervals for the means

We did find a significant interaction between the effects of zidovudine and age on left ventricular mass in infants without HIV infection (Table 4). The mean left ventricular mass in infants exposed to zidovudine was higher at the first echocardiogram than in those never exposed (13.0 g vs. 12.3 g), lower at 4 months (18.7 g vs. 19.6 g) and 8 months (22.4 g vs. 23.9 g), and higher at 12 months (28.9 g vs. 27.4 g). Therefore, there was no consistent effect of zidovudine exposure on left ventricular mass.

Long-Term Effects on Left Ventricular Structure and Function

An effect of zidovudine on echocardiographic measures was not identified among either HIV-infected or non–HIV-infected children. No clinically important differences were found between zidovudine-exposed and unexposed children for any of the four echocardiographic measures between 14 months and 5 years of age (data available elsewhere*).

Depressed Fractional Shortening

To address the possibility that zidovudine exposure may have an extreme effect on a vulnerable subgroup of infants, rather than a consistent effect among all infants, we tested whether the proportion of children with fractional shortening of 25 percent or less (defined as depressed fractional shortening) differed according to postnatal zidovudine exposure. No significant differences were found between exposed and unexposed infants, either in the HIV-infected or the non–HIV-infected group, in the first 14 months of life. None of the 12 HIV-infected infants who were continuously exposed to zidovudine for 14 months had fractional shortening of 25 percent or less by 10 months of age. Among the 46 HIV-infected infants without zidovudine exposure, 9 percent (2 of 22 tested) had depressed fractional shortening at 0 to 1.5 months, as did 6 percent (2 of 33) at >1.5 to 6 months, and 7 percent (2 of 28) at >6 to 10 months. By six weeks of age, 12 percent (3 of 25 tested) of the 36 non–HIV-infected infants who had been exposed to zidovudine for six weeks or less had fractional shortening of 25 percent or less. Depressed fractional shortening was not identified in these 36 infants after 6 weeks of age (0 of 25 tested at >1.5 to 6 months and 0 of 15 at >6 to 10 months). Among the 346 non–HIV-infected infants never exposed to zidovudine after birth, 4 percent (7 of 170 tested) had depressed fractional shortening at 0 to 1.5 months and 1 percent (3 of 283) had depressed fractional shortening at >1.5 to 6 months. None of the non–HIV-infected infants without postnatal zidovudine exposure had depressed fractional shortening between 6 and 10 months of age. After 10 months of age, no infants had depressed fractional shortening, regardless of zidovudine exposure or HIV status.

DISCUSSION

In our study, infants born to HIV-infected women and exposed to zidovudine were no more likely to have abnormal left ventricular structure and function than were infants who did not have zidovudine treatment throughout the first 14 months of life. These results support the findings of a previous retrospective study that used longitudinal cardiac data in older children to compare those who had been exposed to zidovudine with those who had not been exposed to zidovudine,11 as well as recent studies by the National Institutes of Health AIDS Clinical Trials Group.16 However, a recent study from France7 suggested that a negative cardiac effect may persist over a considerable period after exposure to zidovudine in infants without HIV infection and infants born to HIV-infected mothers. That study, however, did not have a control group, whereas our study had an uninfected cohort. Similarly, persistent cardiotoxicity was observed in neonatal monkeys exposed to zidovudine in utero.1–3 Both our study and the French study7 provide evidence that cardiotoxicity is not a common complication of zidovudine treatment in children.

In looking at the percentage of children with depressed fractional shortening as an indication of a detrimental effect of zidovudine within a vulnerable subgroup, we are limited by our small sample. The samples in our study are too small to provide an accurate estimate of the frequency of an uncommon toxic effect. Also, the small number of infants exposed to zidovudine who were followed after 14 months of age is likely to be inadequate for us to detect late-emerging events. We may also have missed instances of depressed fractional shortening in longer-term follow-up, because the sickest children may not have been able to attend follow-up visits. In addition, during longer-term follow-up of the HIV-infected subgroup, the effect of zidovudine becomes more ambiguous, because these children are exposed to many other drugs, and it is hard to ascribe changes specifically to zidovudine. Finally, the effects of dosage were not assessed in this study.

Gerschenson et al.1–3 found profound changes in the structure and function of cardiac-muscle mitochondria in neonatal monkeys exposed to zidovudine at the end of gestation. In contrast, we found no clear association between zidovudine and left ventricular structure or function, as assessed by echocardiography, in neonates without HIV infection who received zidovudine as part of postnatal prophylaxis, even when echocardiograms were obtained at the time the children were taking the drug. Although our intensive follow-up included children only up to the age of 14 months, the data of Gerschenson et al.1–3 indicate that subclinical dysfunction, if present, should be seen at birth or soon after. However, no such manifestations were observed in our cohort.

We found no evidence of acute or chronic adverse cardiac effects in non–HIV-infected infants exposed to zidovudine in the perinatal period. This absence of evidence of toxicity is reassuring, given the reports of Gerschenson et al.1–3 and Blanche et al.7 Our echocardiographic data suggest that the benefits of zidovudine during pregnancy in reducing vertical transmission of HIV outweigh the reported cardiac risks — a conclusion similar to that of other studies.7,23 Any decision not to initiate zidovudine therapy, or to stop it, should be made with great caution.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NO1-HR-96037, NO1-HR-96038, NO1-HR-96039, NO1-HR-96040, NO1-HR-96041, NO1-HR-96042, and NO1-HR-96043) and in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RR-00865, RR-00188, RR-02172, RR-00533, RR-00071, RR-00645, RR-00685, and RR-00043).

APPENDIX

The following is a partial list of participants in the study group, with principal investigators identified by asterisks (a complete list of study participants can be found in an earlier report22):

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: H. Peavy (project officer), A. Kalica, E. Sloand, G. Sopko, and M. Wu; Steering Committee Chair: R. Mellins; Clinical Centers: Baylor College of Medicine, Houston — W. Shearer,* N. Ayres, J.T. Bricker, A. Garson, L. Davis, P. Feinman, and M.B. Mauer; University of Texas, Houston — D. Mooneyham and T. Tonsberg; Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston — S. Lipshultz,* S. Colan, L. Hornberger, S. Sanders, M. Schwartz, H. Donovan, J. Hunter, E. McAuliffe, N. Moorthy, P. Ray, and S. Sharma; Boston Medical Center, Boston — K. Lewis; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York — M. Kattan,* W. Lai, D. Carp, D. Lewis, and S. Mone; Beth Israel Medical Center, New York — M.A. Worth; Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University, New York — R. Mellins,* F. Bierman* (through May 1991), T. Starc, A. Brown, M. Challenger, and K. Geromanos; University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine, Los Angeles — S. Kaplan,* Y. Al-Khatib, R. Doroshow, J. Isabel-Jones, R. Williams, H. Cohen, S. Golden, K. Simandle, and A.-L. Wong; Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles — A. Hohn, B. Marcus, A. Gardner, and T. Ziolkowski; Los Angeles County Hospital, Los Angeles — L. Fukushima; Clinical Coordinating Center: The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland — K.A. Easley,* M. Kutner* (through December 1999), M. Schluchter* (through April 1998), J. Goldfarb, D. Moodie, C. Chen, S. Husak, V. Konig, S. Rao, A. Shah, S. Sunkle, and W. Zhang; Policy, Data, and Safety Monitoring Board: H. Rigatto (chairman), E.B. Clark, R.B. Cotton, V.V. Joshi, P.S. Levy, N.S. Talner, P. Taylor, R. Tepper, J. Wittes, R.H. Yolken, and P.E. Vink.

Footnotes

See NAPS document no. 05568 for 9 pages of supplementary material. To order, contact NAPS, c/o Microfiche Publications, 248 Hempstead Tpke., West Hempstead, NY 11552.

References

- 1.Gerschenson M, Erhart SW, Paik CY, Poirier MC. The mitochondrial (mt) genotoxicity of transplacental exposure to 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) in fetal skeletal and cardiac muscle in patas monkeys. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1999;40:386. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idem. Transplacental exposure to 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine (AZT) is genotoxic to fetal skeletal and cardiac muscle mitochondria. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(Suppl):A164. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerschenson M, Ewings EL, Paik CY, et al. Fetal mitochondrial dysfunction in Erthyrocebus Patas monkeys exposed in utero to zidovudine. Proceedings of the Second Conference on Global Strategies for the Prevention of HIV Transmission from Mothers to Infants; Montreal. September 1–6, 1999; p. 70. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis W. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiviral nucleosides used in AIDS: insights derived from toxic changes observed in tissues rich in mitochondria. In: Lipshultz SE, editor. Cardiology in AIDS. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1998. pp. 317–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow H-H, Li P, Brookshier G, Tang Y. In vivo tissue disposition of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine and its anabolites in control and retrovirusinfected mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:412–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson TA, Binienda ZK, Lipe GW, Gillam MP, Slikker W, Jr, Sandberg JA. Transplacental pharmacokinetics and fetal distribution of azidothymidine, its glucuronide, and phosphorylated metabolites in late-term rhesus macaques after maternal infusion. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:453–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanche S, Tardieu M, Rustin P, et al. Persistent mitochondrial dysfunction and perinatal exposure to antiretroviral nucleoside analogues. Lancet. 1999;354:1084–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin-Garcia J, Goldenthal MJ, Ananthakrishnan R, et al. Specific mitochondrial DNA deletions in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;31:306–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idem. Mitochondrial function in children with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1996;19:309–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01799259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domanski MJ, Sloas MM, Follmann DA, et al. Effect of zidovudine and didanosine treatment on heart function in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr. 1995;127:137–46. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipshultz SE, Orav EJ, Sanders SP, Hale AR, McIntosh K, Colan SD. Cardiac structure and function in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection treated with zidovudine. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1260–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210293271802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Startari R, Fesslova V, Pinzani R, et al. Cardiovascular involvement in children with HIV infection. In: Imai Y, Momma K, editors. Proceedings of the Second World Congress of Pediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery. Armonk, N.Y.: Futura Publishing; 1998. pp. 1156–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardoso JS, Moura B, Mota-Miranda A, Goncalves FR, Lecour H. Zidovudine therapy and left ventricular function and mass in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Cardiology. 1997;88:26–8. doi: 10.1159/000177305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark RI, Garland M, Daniel SS, Leung K, Myers MM, Tropper PJ. Fetal cardiorespiratory and neurobehavioral response to zidovudine (AZT) in the baboon. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 1997;4:183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal–infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1173–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culnane M, Fowler MG, Lee SS, et al. Lack of long-term effects of in utero exposure to zidovudine among uninfected children born to HIV-infected women. JAMA. 1999;281:151–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz ML, Cox GF, Lin AE, et al. Clinical approach to genetic cardiomyopathy in children. Circulation. 1996;94:2021–38. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipshultz SE, Orav EJ, Sanders SP, McIntosh K, Colan SD. Limitations of fractional shortening as an index of contractility in pediatric patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr. 1994;125:563–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, Orav EJ, et al. Left ventricular structure and function in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus: the prospective P2C2 HIV Multicenter Study. Circulation. 1998;97:1246–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.13.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starc TJ, Lipshultz SE, Kaplan S, et al. Cardiac complications in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 1999;104:219. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.e14. abstract. (See http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/104/2/e14.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, Orav EJ, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and mortality in HIV-infected children: the prospective P2C2 HIV Multicenter Study. Circulation. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1542. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The P2C2 HIV Study Group. The pediatric pulmonary and cardiovascular complications of vertically transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (P2C2 HIV) infection study: design and methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1285–94. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00230-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris AAM, Carr A. HIV nucleoside analogues: new adverse effects on mitochondria? Lancet. 1999;354:1046–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]