Abstract

Patient: Male, 67

Final Diagnosis: Metastatic gastric carcinoma

Symptoms: Painful swelling of soft tissue

Medication: Folinic acid • fluouracil • irinotecan

Clinical Procedure: Radiological-pathological work-up

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Gastric carcinoma is one of the most common malignancies in the world. Skeletal muscle metastases from gastric carcinoma are rare.

Case Report:

We report a case of a 67-year-old man patient with skeletal muscle metastasis developing from gastric carcinoma. He had a painful swelling of the left thigh. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan with enhancement showed pulmonary thromboembolism. Despite heparin therapy, edema and pain of the lower limbs increased bilaterally, so the patient underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which documented an altered signal intensity in the upper third of his thighs bilaterally. Furthermore, the examination of the ultrasound (US)-guided biopsy specimen of the left gluteal muscle showed signet ring cell adenocarcinoma metastasis. An upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy confirmed a gastric ulceration, with a biopsy positive for signet ring cell adenocarcinoma. Because of the advanced stage of disease, the patient underwent only supportive care and died 74 days after admission.

Conclusions:

Skeletal muscle metastasis may be the initial presentation of gastric carcinoma and diagnosis could be difficult. Biopsy is mandatory for diagnosis.

MeSH Keywords: Muscle, Skeletal; Neoplasm Metastasis; Stomach Neoplasms

Background

Gastric carcinoma is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death in the world. The most frequent metastatic sites of gastric carcinoma are regional lymph nodes, liver, peritoneum, lung, and bone. In the literature, skeletal muscle metastases from gastric carcinoma have been reported rarely [1,2]. We report a case of a patient hospitalized primarily for a swelling of lower limbs, which was diagnosed as skeletal muscle metastases developing from gastric carcinoma.

Case Report

A 67-year-old white man was admitted on March 2013 due to a painful swelling of the left thigh, appearing about a month before. On admission, he was 170 cm in height and 80 kg in weight. He had a temperature of 36.4°C, heart rate 112 beats/min, blood pressure 140/70 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 89%. He was a non-smoker and his medical history was uneventful. He had not been taking any medication. Because we suspected deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, he underwent a chest computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast medium, which showed a thrombus in the inferior lobar branch of the right pulmonary artery, without parenchymal abnormalities. The Doppler US of the lower limbs was negative. Subsequently, due to the presence of the painful swelling of the left thigh, he underwent CT scan of the pelvis and thighs, which showed increased enhancement in the left gluteus, with a small colliquative area as an “inflammatory injury”, without marks of deep vein thrombosis of the lower limbs. Therapy with low molecular-weight heparin was prescribed., but after a few days we observed a worsening of clinical conditions, with impossibility of ambulation and sitting, caused by increased edema and pain in his lower limbs bilaterally. Therefore, he underwent a pelvic MRI that documented altered signal intensity in the upper third of his thighs bilaterally, associated with colliquative-necrotic area (4×2×9 cm) in the right adductor muscle (Figure 1) and edema of subcutaneous soft tissue of hips, sacral region, and thighs bilaterally. Subsequently, a US-guided biopsy of the left gluteal muscle was performed. A histological diagnosis of metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma was done (Figures 2 and 3). Upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy showed an ulceration of the antrum of the stomach, with irregular margins. The histologic examination of this lesion showed signet ring cell adenocarcinoma. At this point, a total body CT scan with contrast medium showed a widespread mucosal thickening of the gastric wall and multiple perigastric and lumboaortic lymphadenopathies, excluding other distant metastases of gastric carcinoma. After a multidisciplinary evaluation, considering the advanced stage of disease (stage IV) and the absence of gastrointestinal tract symptoms, including bleeding and gastrointestinal tract obstruction, chemotherapy with FOLFIRI regimen was planned. After 2 months, the clinical conditions of the patient worsened with evidence of widespread metastatic disease. He underwent only supportive care and died of disease in June 2013.

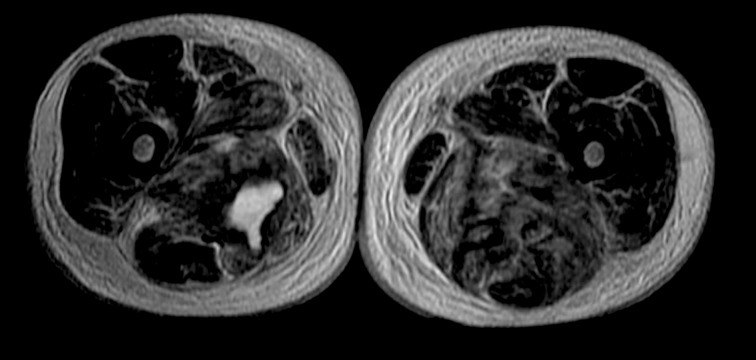

Figure 1.

Axial T2-weighted MRI of thighs shows altered signal intensity in the upper third of the thighs bilaterally, with colliquativenecrotic area (4×2×9 cm) in the right adductor muscle.

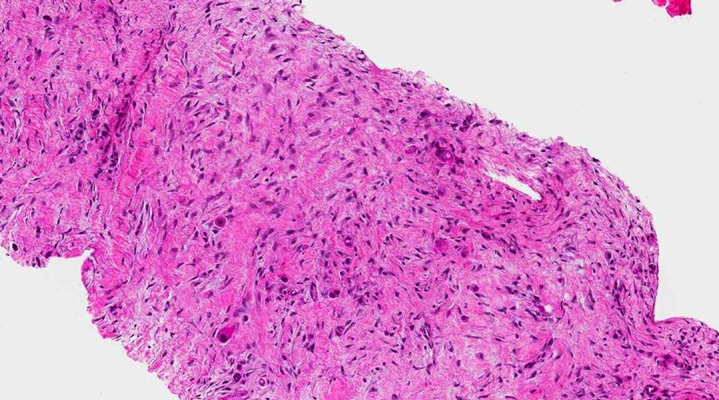

Figure 2.

Core biopsy in which scattered neoplastic epithelial cells with atypical nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasms, immersed in a desmoplastic reaction, are evident (H&E: 100× total magnification).

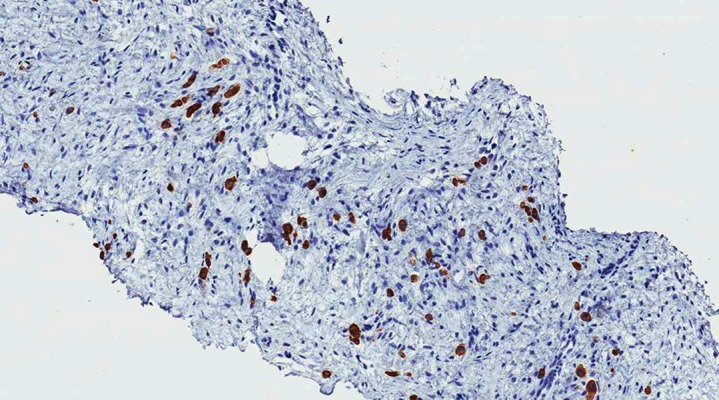

Figure 3.

Neoplastic cells are highlighted by anti-pan cytokeratin antibody (AE1/AE3: 100× total magnification).

Discussion

Skeletal muscle metastasis is rare [2–4]. Most common malignancies metastasizing to skeletal muscles are lung, kidney, bladder, and gastrointestinal tract carcinomas. Lower limbs are the most common anatomical sites of muscle metastases [4,5].

The incidence of skeletal metastasis is unknown, but approximately 0.16–0.03% has been reported in clinical practice, and 0.8% in an autopsy study [6]. Gastric cancer rarely metasta-sizes to skeletal muscle and most cases of muscle metastasis are associated with advanced disease and poor prognosis. In addition to skeletal muscle, many other unusual sites of metastasis from gastric carcinoma have been reported in the literature – pancreatic, cutaneous, parotid, gingival, breast, testicular, uterine, and fallopian tube metastases [7–11]. Because of their rarity and particular clinical characteristics, these metastases are challenging to diagnose and are frequently part of a widespread metastatic disease.

Although skeletal muscle is a vascular tissue and constitutes more than half of the body mass, hematogenous metastases to muscle have been reported to be uncommon. The reason for the rarity of metastases in skeletal muscle is unclear, but it could be related to factors that make skeletal muscle hostile to metastatic spread, such as: 1) the prevention of settlement of tumor cells by the inconstant blood flow and changing tissue pressure due to muscular contractions, 2) the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by lactic acid (an inhibitory factor), and 3) lower pH values in the muscle [3,12,13].

Skeletal muscle metastasis generally manifests itself as a “painful mass”, but it may be an incidental finding in imaging studies in patients without symptoms [5,14]. Sometimes, as in our case, it is the initial presentation of an undiagnosed primary tumor, with or without any other detectable metastases [1,2,5,15].

Most skeletal muscle metastases are detected on CT scan due to its routine use in oncologic staging, but MRI is considered superior to CT scanning for detecting and characterizing muscle abnormalities [4,5,14]. Muscle metastatic lesions frequently reveal isointense signal to muscle, with ill-defined margins on T1-weighted MRI, and heterogeneous signal intensity with well-defined margins, in addition to peritumoral edema on T2-weighted images [5,14]. On the gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced MRI, Tuoheti et al. showed that extensive peritumoral enhancement associated with central necrosis was one of the characteristic features of skeletal muscle metastasis and was found in 92% of their cases [5].

Although considered rare, Haygood et al., in a review of the current literature, reported a muscle metastases rate of about 1.6%, suggesting that radiologists need to be alert to their presence when interpreting staging examinations in cancer patients, thus avoiding possible delay of diagnosis [16]. Any painful soft-tissue mass occurring in patients with a known history of carcinoma is highly suspicious for skeletal muscle metastasis [5]. When skeletal muscle metastasis is the initial presentation, the diagnosis is more difficult, as in our case. Then, in the presence of a mass to skeletal muscle, being easily attackable, biopsy is considered mandatory for diagnosis [4–6].

Therapeutic options may include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgical excision [4,5]. Radiotherapy may effectively relieve the pain and decrease the size of metastatic lesions [2,5,6,17]. To relieve pain and, although uncommon, to prolong the survival time, surgical excision may be helpful in carefully selected patients, such as those with a painful isolated mass and in absence of other metastatic sites [4,5]. Chemotherapy frequently is the only option, due to advanced disease with multiple metastatic sites.

The prognosis principally depends on the primitive tumor type, but is generally poor because there are multiple disseminated metastases. In our case, the critical clinical conditions of the patient and the advanced pathological stage of the tumor, with sudden progression, made it impossible to perform radiotherapy or surgical excision. We therefore provided palliative care only.

Conclusions

Skeletal muscle metastasis, as in our case, may be the initial presentation of an undiagnosed gastric carcinoma, with or without any other detectable metastases. As in this case, diagnosis may be difficult and needle biopsy is mandatory. Skeletal muscle metastasis appears have poor prognosis but treatment may provide satisfactory results. Therefore, we believe that any skeletal muscle mass should be considered suspicious and biopsy should be performed to avoid delay of diagnosis.

References:

- 1.Pestalozzi BC, von Hochstetter AR. Muscle metastasis as initial manifestation of adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1998;128(38):1414–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbaum LH, Nicholas JJ, Slasky BS, et al. Malignant myositis ossificans: occult gastric carcinoma presenting as an acute rheumatic disorder. Am Rheum Dis. 1984;43:95–97. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seely S. Possible reasons for the high resistance of muscle to cancer. Med Hypotheses. 1980;6(2):133–37. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(80)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herring CL, Jr, Harrelson JM, Scully SP. Metastatic carcinoma to skeletal muscle. A report of 15 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355:272–81. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuoheti Y, Okada K, Osanai T, et al. Skeletal muscle metastases of carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34(4):210–14. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tougeron D, Hamidou H, Dujardin F, et al. Unusual skeletal muscle metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33(6–7):485–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wente MN, Bergmann F, Fröhlich BE, et al. Pancreatic metastasis from gastric carcinoma: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi WJ, Jue MS, Ko JY, Ro YS. An unusual case of carcinoma erysipelatoides originating from gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(3):375–78. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoneveld JM, Hesp WL, Teune TM. Parotid metastasis from a gastroesophageal carcinoma: report of a case. Dig Surg. 2007;24(1):68–69. doi: 10.1159/000100922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimoyama S, Seto Y, Aoki F, et al. Gastric cancer with metastasis to the gingiva. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(7):831–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2002.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luk YS, Ka SY, Lo SS, et al. An unusual case of gastric cancer presenting with breast metastasis with pleomorphic microcalcifications. J Breast Cancer. 2012;15(3):356–58. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2012.15.3.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss L. Biomechanical destruction of cancer cells in skeletal muscle: a rate-regulator for hematogenous metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1989;7(5):483–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01753809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namba T, Sato T, Grob D. Inhibition of Ehrlich ascites tumors cells by skeletal muscle extracts. Br J Exp Pathol. 1968;49(3):294–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arpaci T, Ugurluer G, Akbas T, et al. Imaging of the skeletal muscle metastases. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(15):2057–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oba K, Ito T, Nakatani C, et al. An elderly patient with gastric carcinoma developing multiple metastasis in skeletal muscle. J Nippon Med Sch. 2001;68:271–74. doi: 10.1272/jnms.68.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haygood TM, Wong J, Lin JC, et al. Skeletal muscle metastases: a three-part study of a not-so-rare entity. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(8):899–909. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beşe NS, Ozgüroğlu M, Dervişoğlu S, et al. Skeletal muscle: an unusual site of distant metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Radiat Med. 2006;24(2):150–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02493284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]