Abstract

Purpose:

To compare real-time dynamic multileaf collimator (MLC) tracking, respiratory amplitude and phase gating, and no compensation for intrafraction motion management during intensity modulated arc therapy (IMAT).

Methods:

Motion management with MLC tracking and gating was evaluated for four lung cancer patients. The IMAT plans were delivered to a dosimetric phantom mounted onto a 3D motion phantom performing patient-specific lung tumor motion. The MLC tracking system was guided by an optical system that used stereoscopic infrared (IR) cameras and five spherical reflecting markers attached to the dosimetric phantom. The gated delivery used a duty cycle of 35% and collected position data using an IR camera and two reflecting markers attached to a marker block.

Results:

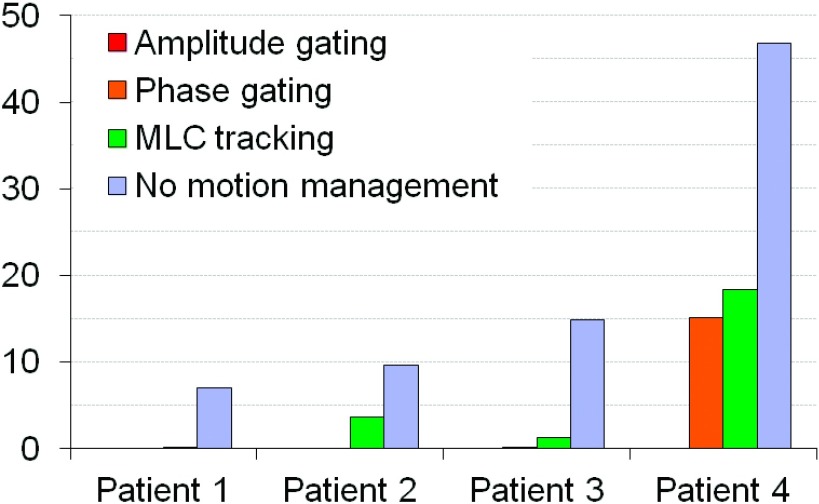

The average gamma index failure rate (2% and 2 mm criteria) was <0.01% with amplitude gating for all patients, and <0.1% with phase gating and <3.7% with MLC tracking for three of the four patients. One of the patients had an average failure rate of 15.1% with phase gating and 18.3% with MLC tracking. With no motion compensation, the average gamma index failure rate ranged from 7.1% to 46.9% for the different patients. Evaluation of the dosimetric error contributions showed that the gated delivery mainly had errors in target localization, while MLC tracking also had contributions from MLC leaf fitting and leaf adjustment. The average treatment time was about three times longer with gating compared to delivery with MLC tracking (that did not prolong the treatment time) or no motion compensation. For two of the patients, the different motion compensation techniques allowed for approximately the same margin reduction but for two of the patients, gating enabled a larger reduction of the margins than MLC tracking.

Conclusions:

Both gating and MLC tracking reduced the effects of the target movements, although the gated delivery showed a better dosimetric accuracy and enabled a larger reduction of the margins in some cases. MLC tracking did not prolong the treatment time compared to delivery with no motion compensation while gating had a considerably longer delivery time. In a clinical setting, the optical monitoring of the patients breathing would have to be correlated to the internal movements of the tumor.

Keywords: tumor tracking, gating, intrafraction motion, arc therapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Motion management during stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) of lung cancer is an important consideration, especially for patients with so large tumor motion that the dose distribution might be affected.1,2 The treatment volume can be extended to increase the probability of the tumor being covered throughout the fraction but this method also increases the dose to the surrounding healthy tissue. Another approach is to adapt the treatment delivery to the motion of the tumor. Gating3 which is used for breast and lung cancer4,5 only allows for beam on when the tumor is inside a predefined motion range. The delivery can be gated based on the amplitude or on the phase of the respiratory motion. Gating adds to the treatment time given that the beam is turned on and off during the treatment, and in addition, the treatment efficiency decreases with increasing delivery accuracy.6 Prolongation of the treatment time increases the risk of patient shifts as well as the discomfort for the patient. Tumor tracking where the target motion is compensated for in real time has been performed using the CyberKnife® robotic treatment system (AccuRay®)7,8 and the gimbaled Linac (VERO™, BrainLab).9 Potential methods that are still under development include tracking using the multileaf collimator (MLC) leaves10–21 and the treatment couch.22,23 For motion management during stereotactic treatments, it would be preferable to use a method that does not add to the treatment time as the treatment time is already long. Real-time dynamic MLC tracking has the potential to accurately compensate for target motion with no increase in the treatment delivery time. The treatment time is also dependent on the treatment technique. The intensity modulated arc therapy (IMAT) technique delivers the treatment in one or several gantry arcs with varying dose rate and gantry speed24,25 and has been shown to be able to deliver a treatment in considerably less time than intensity modulated radiotherapy treatment.26 The purpose of this study was to compare MLC tracking and gating for IMAT SBRT of lung cancer. MLC tracking and gating were compared using real patient data and real patient tumor trajectories. The delivery time, dosimetric accuracy, and the potential margin reduction were evaluated for the different delivery techniques. In addition, the dosimetric error contributions from the target localization, MLC leaf fitting, and leaf adjustment were investigated.

2. METHODS

This study was carried out for four patient cases, selected from 15 patients included in a prospective trial evaluating marker implantation in patients with peripheral lung tumors referred for SBRT. For this study, seven out of the fifteen patients were excluded because the quality of the fluoroscopy movies was inadequate. Three patients were excluded because the tumor movement estimated with a 4DCT scan was too small, <0.4 cm peak-to-peak to motivate motion management with MLC tracking or gating and finally one patient was excluded due to technical difficulties with the treatment plan.

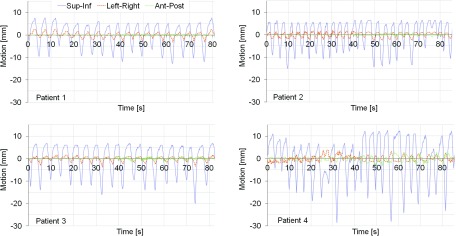

For all four patients, the tumor was located in the lower lobe of the lung. The 4DCT scan and fluoroscopic movies were acquired without respiratory coaching for all patients. Individual motion trajectories were created based on the fluoroscopy movies in which the position of the internal marker or the center of the tumor was determined in two orthogonal image sequences. The sequences were 45 s long and acquired in the sagittal and coronal planes, respectively. The motion in the left–right (LR) direction in the sagittal sequence was estimated using linear correlation between the LR and the superior–inferior (SI) motion observed in the coronal sequence, while the anterior–posterior (AP) motion in the coronal sequence was estimated using linear correlation between the AP and the SI motion observed in the sagittal sequence. The two sequences were put together and looped for the experiments. The traces were put together at the first/last point in the traces that was in the same breathing phase (inhale or exhale) and that had a positional difference smaller or equal to the maximum difference between two subsequent points in the original fluoroscopy traces in all three directions. A first-order Butterworth low-pass filter was used to reduce the noise in the trajectories. The traces were normalized in three different ways for the experiments to distribute the errors evenly in each direction and to simulate optimal setup for each technique. For the measurements with no motion compensation and for the measurements with MLC tracking, the average position of each trajectory was chosen as origin (Fig. 1). For the gated delivery, the origin was set to the average position of the part of the trajectory included in the gating window. The distance between the origin and the gating threshold was determined and used during the experiments when setting the gating window for amplitude gating. During the experiments, the patient tumor motion was simulated using a motion phantom (HexaMotion, ScandiDos) integrated with the dosimetric device.

FIG. 1.

The four patient motion trajectories used to drive the phantom for the dosimetric experiments.

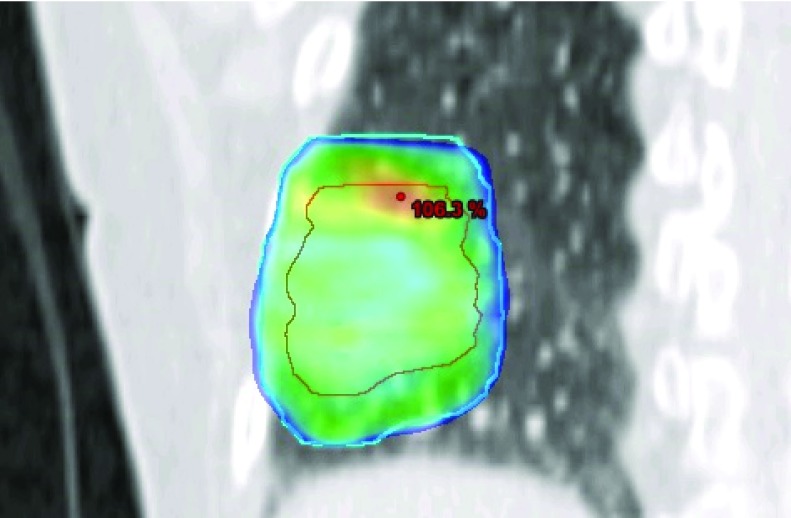

An IMAT plan (RapidArc®) was created for each patient using a research version of Eclipse TPS (version 10). The plan was created using the end expiration phase of the 4DCT scan and had a fractionation dose of 15 Gy. The margins used were the same as those used in the clinic for this patient group; i.e., 1 cm in the craniocaudal direction and 0.5 cm in the AP and LR directions. The plan used two 180° arc fields, 6 MV, a maximum dose rate of 600 MU/min, and collimator angles of 30° and 330°. A leaf position constraint12 was used to make the plan suitable for MLC tracking. The plans were normalized to 100% in target mean and had a fairly homogeneous dose distribution (Fig. 2). The number of monitor units (MU), the homogeneity index (HI),38 the planning target volume (PTV) volume receiving 95% of the prescribed dose (V95), the maximum dose to the PTV, and the volume of the PTV for the four patient plans are presented in Table I.

FIG. 2.

Dose color wash for patient 1 in a frontal view at isocenter showing doses above 95% of the target mean dose. The outer contour (blue line) is the PTV (target) outline and the inner contour (red line) is the outline of the GTV.

TABLE I.

The number of MU, the HI (Ref. 38), the PTV volume receiving 95% of the prescribed dose (V95), the maximum dose to the PTV, and the volume of the PTV for the four patient plans.

| Number of MUs | HI | PTV V95 (%) | PTV max dose (%) | PTV volume (cm3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 2788 | 0.104 | 96.66 | 107.2 | 98.88 |

| Patient 2 | 3354 | 0.076 | 98.06 | 105.3 | 149.47 |

| Patient 3 | 3208 | 0.076 | 97.86 | 105.3 | 77.30 |

| Patient 4 | 2994 | 0.084 | 97.26 | 105.2 | 47.02 |

The plans were delivered to a dosimetric phantom (Delta,4 ScandiDos) using a Novalis TX™ linear accelerator with a high definition MLC (HD-MLC). The dosimetric phantom contains two orthogonal detector arrays, one which passes through the entire diameter of the phantom and two wing detector boards which are separated to allow the main detector board to pass between them. The detector boards are surrounded by PMMA slabs creating a cylindrical volume with a diameter of 22 cm and a length of 40 cm. The detector arrays contain 1069 p-Si diodes, separated by 0.5 cm in the central 6 × 6 cm2 area of the detector arrays and by 1 cm in the remaining area (up to 20 × 20 cm2). The diodes are disc shaped with volumes of 0.04 mm3 and areas of 0.0078 cm2. The gantry angle is measured using an inclinometer attached to the gantry or accelerator head and correction for gantry angle are applied to the measurements. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Experimental set-up of the Delta4 phantom with the Hexamotion platform, along with the optical monitoring systems used for the DMLC tracking input (ExacTrac) and gating (RPM).

The gated delivery was performed using the Real-time Position Management™ (RPM) system (Varian). The system used an infrared (IR) camera and two reflecting markers attached to a marker block to acquire position information. In a clinical situation, the marker block is positioned on the patient chest wall and x-ray images are used to check the correlation between the external marker movements and the position of the tumor.27 However, in this study, the gated delivery was performed based on the actual target motion in the SI direction. The IR camera was therefore positioned lateral to the phantom and rotated to measure the SI motion rather than the AP motion. The marker block was positioned approximately 2 m from the camera and rotated the same way as the camera. It was attached to the dosimetric phantom using an extension to ensure that the markers would be visible for the IR camera as the gantry rotated. The system used the distance between the two markers to determine the absolute target motion in the SI direction. A gating window at the end of exhale6 and a 35% duty cycle were chosen for both amplitude and phase gating. The window for amplitude gating was set in the motion strip chart in the RPM software by moving the horizontal lines and the phase gating thresholds were set using the phase dial for the respiratory cycle.

The MLC tracking delivery was performed using a research (preclinical) software17 and an optical system that uses stereoscopic IR cameras and reflective spherical markers (the optical part of the ExacTrac system, Brainlab)28,29 for real-time position data input. The position data were acquired using two cameras emitting IR light and passive reflective spheres attached to the phantom surface. It should be noted that in a clinical situation, the markers would be attached to the patient chest wall, not to the actual target, and the correlation between the optical markers and the target could be established using x-ray images.30 An alternative internal position signal, for both MLC tracking and gating, is electromagnetic guidance which has been used for human lung tumor implantation.31 A tracking algorithm calculated new MLC leaf positions to adjust for the target movements, and a prediction algorithm32 compensated for the delay time of the system (260 ms). The new leaf positions were then sent to the MLC controller to guide the positioning of the MLC leaves. For each patient, three measurements were performed with each technique and the time to deliver the plans was determined using the treatment machine timer.

Motion management using MLC tracking requires the jaws to have a wider opening than for a standard radiotherapy treatment in order to allow for peripheral MLC leaves to correct for the target movements during the treatment. To reduce the interleaf leakage, the tracking system moves the ends of the closed adjacent leaves to under one of the jaws. The four leaf pairs closest to the opened aperture were, however, kept adjacent to the opening to enable a quick response of the system. All plans in this study had wider jaw opening than what would be used in a standard treatment, also for the delivery without tracking. Because no action was taken to reduce the interleaf leakage when MLC tracking was not used, there was a dosimetric difference between delivery of the same plan with and without MLC tracking, also for a static target. For this reason, the motion management capabilities of the MLC tracking system were evaluated considering the dose distribution measured with a static phantom with the MLC tracking system connected as the dose distribution that would be obtained with optimal compensation of the motion. In the same way, for all other measurements, a static measurement with the tracking system disconnected was considered to represent optimal compensation of the motion. By evaluating the results with respect to delivery of the same plan with a static phantom, any discrepancies between the TPS and the delivered dose did not influence the results. The results were evaluated using 2D gamma index evaluation with criteria 2% and 2 mm in the two 2D detector boards of the Delta.4 The detector points receiving less than 10% of the isocenter dose were excluded from the evaluation since these points are likely to pass the evaluation for all cases.

The dosimetric error contributions in the motion management process were calculated for two of the patients as described by Poulsen et al.33 For MLC tracking, the dosimetric error contributions are (i) target localization errors which make the tracking program attempting to shift the planned MLC aperture to a slightly wrong position, (ii) MLC leaf fitting errors due to the finite leaf width, and (iii) leaf adjustment errors due to the finite leaf speed. For gated delivery, (ii) does not apply as there is no real-time leaf fitting, i.e., only (i) and (iii) contributed. Here, the target localization error corresponds to the residual motion within the gating window. The relative importance of the error contributions is expressed as the underexposed area (Au) which is the area in beam’s eye view that should have been exposed to radiation but was shielded by a MLC leaf, and the overexposed area, Ao, which is the area that should have been shielded by a MLC leaf but was exposed to radiation. Au and Ao were calculated offline for each of the three MLC shaping steps individually as well as for all three steps combined.

The clinical benefit of using motion compensation for the individual patient cases in this study was investigated by calculating the reduction of the margins possible with the different delivery techniques. The calculations were based on a margin recipe presented by Van Herk et al.34 that uses a combination of systematic (treatment preparation) and random (treatment execution) variations to estimate the PTV margin. Although the appropriate margin recipe for single fraction or hyperfractionated treatment is still an area of investigation, we will use van Herk’s margin recipe for the lung SBRT cases studied here. This study focused on the benefit of using MLC tracking or gating compared to treatment with no motion compensation and therefore, the difference in the required PTV margin for delivery with and without the use of MLC tracking or gating was calculated. Using the notation suggested by van Herk et al., this can be described as

| (1) |

βσ represents the distance between the 95% and 50% isodoses surface of the dose distribution with σ describing the total standard deviation (SD) for all random variations, and β is equal to 1.64.34 The margin recipe is valid provided that the 50% isodose surface does not change in position as a result of blurring. This position was therefore measured for dose profiles measured with and without motion for the four patients. The total SD for all random variations depends on the SD for the target motion (σmotion), the SD for the setup (σset-up), and the SD describing the width of the penumbra, σpenumbra, according to

| (2) |

By assuming daily IGRT, the σset-up of the patients was set to 1 mm in the SI direction. The σpenumbra in the lung was found by measuring the distance between the 95% and 50% isodoses surface for each patient in the treatment planning system and dividing this value with β. The σmotion was calculated based on the measurements with no motion compensation, MLC tracking, and gating, respectively. The central diode values in the SI direction in the Delta4 were used to calculate the value of βσ for each patient with the different delivery techniques. The value of σmotion could then be derived by the relation

| (3) |

The standard deviation for the variations in setup and the width of the penumbra for the Delta4 measurements, σset-up,D4 and σpenumbra,D4 were estimated by calculating the average βσ for static measurements with no motion compensation for each patient. In this way, the effect of motion on the delivered dose could be isolated by determining βσ for the measured dose with the different motion compensation techniques as well as without motion compensation, and then account for the uncertainties from the set up as well as of the penumbra width in the Delta4 by determining βσ for measurements without motion. The average value of βσNo motion compensation was used in the calculations since the measurements were performed three times with no motion compensation.

3. RESULTS

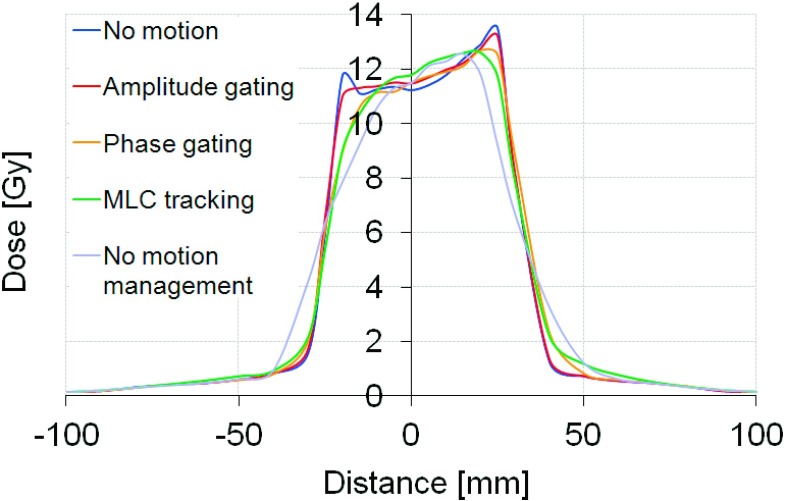

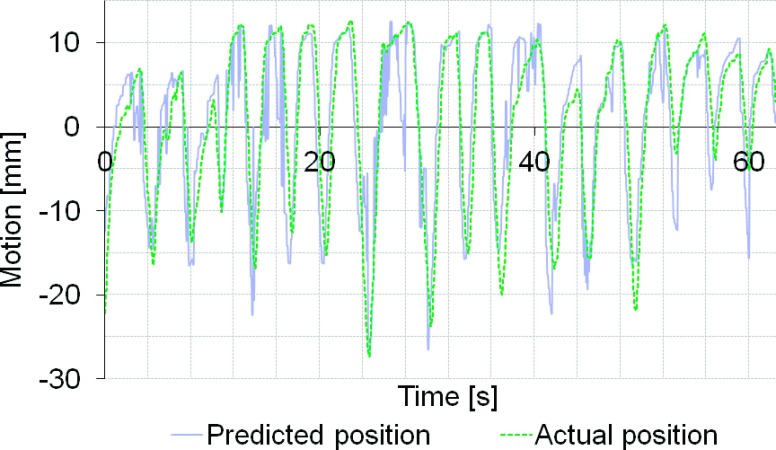

Plan delivery to a moving target without any motion management resulted in adverse effects on the delivery accuracy for all cases. The average gamma index failure rate (2% and 2 mm criteria) ranged from 7.1% to 46.9% for the different patients. Figure 4 shows an example of the dose-smearing effect due to motion for patient 4. Both MLC tracking and gating improved the dosimetric accuracy in all cases. Amplitude gating had the highest accuracy with less than 0.1% failure rate for all patients. Phase gating and MLC tracking showed a high dosimetric accuracy in three of the cases with an average gamma index failure rate of <0.14% (phase gating) and <3.7% (MLC tracking), respectively. Patient 4 had an average failure rate of 15.1% with phase gating and 18.3% with MLC tracking and it should be noted that this patient had the largest dosimetric errors due to target movements when it was not compensated for, giving 46.9% failure rate. The recorded tumor motion of patient 4 was large and highly irregular and was shown to be difficult to predict during the MLC tracking delivery (Fig. 5). The average gamma index failure rates for the different techniques are shown in Fig. 6.

FIG. 4.

Central dose profiles in the SI direction for patient 4.

FIG. 5.

Target position predicted by the MLC tracking system and actual position of the target for patient 4.

FIG. 6.

Average gamma index failure rate with criteria 2% and 2 mm.

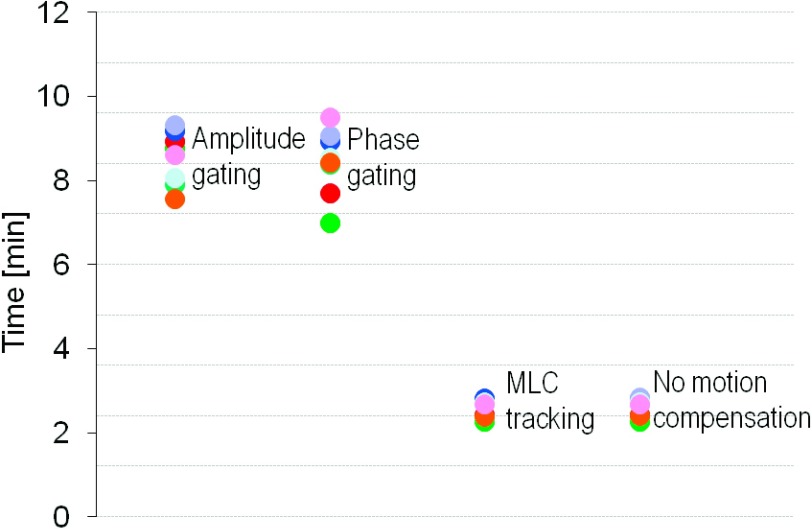

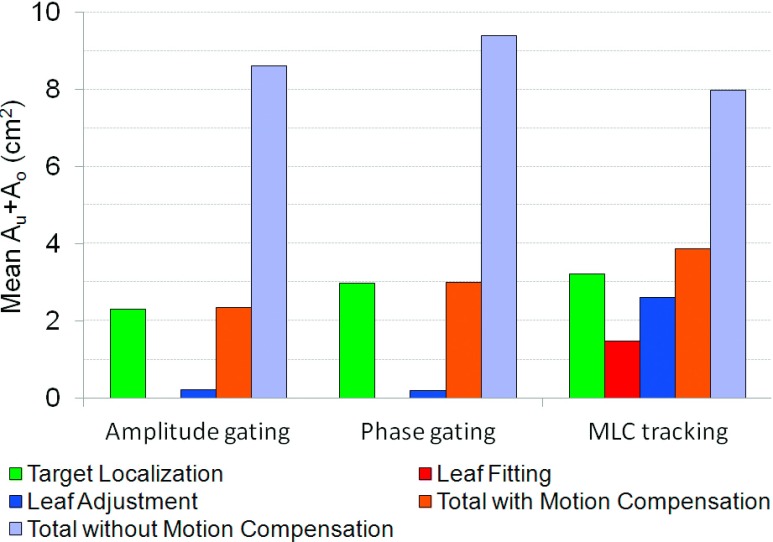

The average delivery time was approximately three times longer with gating than with MLC tracking (Fig. 7). The average delivery time per treatment field was 8.5 min for amplitude gating, 8.6 min for phase gating, and 2.6 min for MLC tracking and for delivery with no motion compensation. MLC tracking did not prolong the treatment time compared to delivery with no motion management. The evaluation of the dosimetric error contributions showed that the majority of the errors in the gated delivery originated from the target localization process, i.e., residual motion within the gating window (Fig. 8). For the delivery with MLC tracking, all three error contributors had a substantial part in the total error, although the target localization was the largest error contributor also for this technique, mainly because of errors in the target position prediction.

FIG. 7.

Average treatment delivery time. The dots (different colors) represent treatment fields for the four patients.

FIG. 8.

Average value of the dose-rate weighted average sums of the over and underexposed areas for patient 1 and 2.

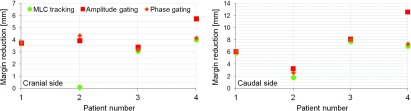

The position of the 50% isodose surface was the same for dose profiles measured with and without motion. The distance between the 50% isodose surface and the isocenter was −35 and +35 mm (patient 1), −44 and +44 mm (patient 2), −35 and +37 mm (patient 3), and −24 and +31 mm (patient 4). The margin reduction enabled with MLC tracking and gated delivery is shown in Fig. 9. For three of the patients, a larger reduction of the margin was enabled on the caudal side of the tumor. For patient 1 and 3, MLC tracking and gating enabled about the same reduction of the margins but for the other two patients, gating gave a larger reduction than MLC tracking.

FIG. 9.

The average margin reduction on the cranial side and the caudal side of the tumor for the different delivery methods. Note the different scales on the y-axis.

4. DISCUSSION

Both MLC tracking and gating improved the dosimetric accuracy of delivery to a moving target for the cases studied. Amplitude gating had the highest dosimetric accuracy for all patients, while phase gating and MLC tracking had a good accuracy for three out of the four patients. The results indicate that the performance of the present version of MLC tracking and phase gating was more sensitive to treatment plan and tumor motion characteristics than amplitude gating as the results varied for the different patients. The dosimetric accuracy with MLC tracking could potentially be improved by reducing the system delay time or improving the prediction function of the system. In the present study, the MLC tracking system was guided by an optical system with stereoscopic IR cameras and had a total delay time of 260 ms. However, MLC tracking has been demonstrated to have shorter delay time when combined with other systems.18,35–37 Only four patients were included in this study so no statistical analysis could be done.

The treatment efficiency was the same with MLC tracking as when no motion management was used. With respiratory gating, the treatment efficiency was substantially reduced with a treatment time of about three times the delivery time with no motion management. An increased treatment time could potentially increase the risk of systematic drifts of the tumor position. The treatment time with gating would have been shorter if a larger duty cycle had been used, however Vedam et al.6 demonstrated a trade off between the range of motion and duty cycle. Potentially, the gating duty cycle could be increased without reducing the delivery accuracy below the accuracy of MLC tracking.

The motion traces created for the experiments in this study were based on real patient tumor motion data and thus represented realistic tumor motion for four different patients. The fluoroscopy movies that were used to create the motion traces were 45 s long, which means that in total, the motion in the SI direction was recorded in 90 s for each patient. The fluoroscopy movies could potentially have been acquired when the patient was breathing differently from the patient’s normal breathing pattern, but any larger temporary deviations are likely to have been detected. Large baseline shifts were not present during the fluoroscopy that was used for creation of the patient’s tumor motion trajectories in this study. Large baseline shifts would probably not affect the delivery with MLC tracking. For amplitude gating, large baseline shifts would most likely decrease the treatment efficiency with maintained dosimetric accuracy or increase the treatment efficiency with reduced dosimetric accuracy depending on the gating window settings as well as the direction of the baseline shift. For phase gating, large baseline shifts would most likely not have any impact on the treatment efficiency, but the dosimetric accuracy could potentially be substantially worsened as the beam could be turned on when the target is far from the planned position.

The evaluation of the dosimetric error contributions showed that the errors in the target localization were the largest source of error for all motion management techniques tested. For amplitude gated delivery, this error originates from the residual motion within the gating window, while phase gating has additional errors caused by irregular breathing cycles. For MLC tracking, the uncertainties in the target position prediction are likely to be the cause of these errors. For MLC tracking, this error is expected to be dependent on the regularity of the target trajectory. For MLC tracking, the error in leaf fitting and leaf adjustment could potentially be reduced by using a MLC with thinner and faster leaves. While the delivery using MLC tracking had contributions from all three steps in the process, the dosimetric errors in the gated delivery were caused by the target localization errors and MLC leaf adjustment only, as no leaf fitting was performed for this delivery technique.

Approximately the same margin reduction was enabled with MLC tracking and gating for two of the patients in this study, but for the other two patients, gating enabled a larger reduction of the margins than MLC tracking. The margin reduction was larger on the caudal side of the tumor for both techniques which might be due to the way the motion trajectories were normalized. For the experiments with no motion compensation, the trajectories were normalized to the average position of the target and since the time in end expiration generally was longer than the time spent in end inspiration, the origin was shifted slightly in the cranial direction (Fig. 1).

The target motion studied was in 3D which means that out of detector plane motion was present during the experiments. The gated delivery was triggered only by motion in the SI direction (although the phantom was moving in 3D), while the delivery with MLC tracking compensated for motion in all three directions so potentially; MLC tracking should have an advantage in these tests. However, the motion amplitude in the LR and AP directions was rather small (<5 mm) so the effect on the measured dose due to out of detector plane motion is likely to be small for gated delivery.

In this study, both MLC tracking and gating were performed based on the actual target movements using optical systems. In a real clinical situation, an optical system alone cannot provide position data of a tumor in the lung but can only be used as a surrogate for the tumor motion.39 In this study, the actual target localization was assumed to be known and only the delivery capabilities of the systems were compared. In a clinical setting, both MLC tracking and gating could be guided by a combination of the optical signal and x-ray imaging. The external motion of the patient’s chest wall could in that way be correlated to the internal movements of the tumor. Cho et al.30 have demonstrated a method for correlation of optical and x-ray signals and shown that the mean 3D errors were less than 1 mm. The additional dosimetric uncertainties of fiducial marker correlation error can be assumed to be similar for MLC tracking and gating, but should be relatively small or even negligible with a correlation error of less than 1 mm, which is clinically feasible.30

5. CONCLUSIONS

Both MLC tracking and gating were able to reduce the dosimetric effects of motion for the cases studied. The dosimetric error for the gated delivery was mostly due to errors in the target localization while for delivery with MLC tracking, all three steps in the motion compensation process had a substantial contribution to the total error. Both techniques could enable reduction of the PTV margin needed to account for treatment execution errors. Gating gave in general a better dosimetric accuracy and enabled a larger margin reduction than tracking but had much lower treatment delivery efficiency than MLC tracking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Dan Ruan (Stanford Cancer Center, Stanford, CA) for development of the MLC tracking code and Herbert Cattell (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) for substantial contributions to the MLC tracking program. The authors also thank Stephan Erbel and Cornel Schlossbauer from Brainlab, Feldkirchen, Germany for supporting the ExacTrac guidance of the MLC tracking delivery. Many thanks to Marianne Aznar, Ivan Vogelius, and Mirjana Josipovic (Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark) for technical assistance. Finally, thanks to Thomas Carlslund and Mikael Olsen (Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark) for technical support during the installation of the tracking system at Rigshospitalet. Research support from Varian Medical Systems, the Niels Bohr Institute (University of Copenhagen), Snedkermester Sophus Jacobsen og hustru Astrid Jacobsens Fond, US NIH/NCI R01-93626, and an NHMRC Australia Fellowship were gratefully acknowledged. The paper was reviewed by Varian Medical Systems prior to submission but no alterations were made.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bortfeld T., Jiang S. B., and Rietzel E., “Effects of motion on the total dose distribution,” Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 14, 41–51 (2004). 10.1053/j.semradonc.2003.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz M., Van der Geer J., van Herk M., Lebesque J. V., Mijnheer B. J., and Damen E. M., “Impact of geometrical uncertainties on 3D CRT and IMRT dose distributions for lung cancer treatment,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 65, 1260–1269 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohara K., Okumura T., Akisada M., Inada T., Mori T., Yokota H., and Calaguas M. J., “Irradiation synchronized with respiration gate,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 17, 853–857 (1989). 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90078-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korreman S. S., Pedersen A. N., Josipovic M., Aarup L. R., Juhler-Nottrup T., Specht L., and Nystrom H., “Cardiac and pulmonary complication probabilities for breast cancer patients after routine end-inspiration gated radiotherapy,” Radiother. Oncol. 80, 257–262 (2006). 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirato H., Shimizu S., Kunieda T., Kitamura K., van Herk M., Kagei K., Nishioka T., Hashimoto S., Fujita K., Aoyama H., Tsuchiya K., Kudo K., and Miyasaka K., “Physical aspects of a real-time tumour-tracking system for gated radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 48, 1187–1195 (2000). 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00748-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedam S. S., Keall P. J., Kini V. R., and Mohan R., “Determining parameters for respiration-gated radiotherapy,” Med. Phys. 28, 2139–2146 (2001). 10.1118/1.1406524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seppenwoolde Y., Berbeco R. I., Nishioka S., Shirato H., and Heijmen B., “Accuracy of tumour motion compensation algorithm from a robotic respiratory tracking system: A simulation study,” Med. Phys. 34, 2774–2784 (2007). 10.1118/1.2739811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Voort van Zyp N. C., Prevost J. B., Hoogeman M. S., Praag J., van der Holt B., Levendag P. C., van Klaveren R. J., Pattynama P., and Nuyttens J. J., “Stereotactic radiotherapy with real-time tumour tracking for non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical outcome,” Radiother. Oncol. 91, 296–300 (2009). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamino Y., Takayama K., Kokubo M., Narita Y., Hirai E., Kawawda N., Mizowaki T., Nagata Y., Nishidai T., and Hiraoka M., “Development of a four-dimensional image-guided radiotherapy system with a gimbaled x-ray head,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 66, 271–278 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho B., Poulsen P. R., Sloutsky A., Sawant A., and Keall P. J., “First demonstration of combined kV/MV image-guided real-time dynamic multileaf-collimator target tracking,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 74, 859–867 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falk M., Munck af Rosenschold P., Keall P., Cattell H., Cho B. C., Poulsen P., Povzner S., Sawant A., Zimmerman J., and Korreman S., “Real-time dynamic MLC tracking for inversely optimized arc radiotherapy,” Radiother. Oncol. 94, 218–223 (2010). 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falk M., Larsson T., Keall P., Cho B. C., Aznar M., Korreman S., Poulsen P., and Munck af Rosenschold P., “The dosimetric impact of inversely optimized arc radiotherapy plan modulation for real-time dynamic MLC tracking delivery,” Med. Phys. 39, 1588–1594 (2012). 10.1118/1.3685583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keall P. J., Sawant A., Cho B., Ruan D., Wu J., Poulsen P., Petersen J., Newell L. J., Cattell H., and Korreman S., “Electromagnetic-guided dynamic multileaf collimator tracking enables motion management for intensity-modulated arc therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 79, 312–320 (2011). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClelland J. R., Webb S., McQuaid D., Binnie D. M., and Hawkes D. J., “Tracking ‘differential organ motion’ with a ‘breathing’ multileaf collimator: Magnitude of problem assessed using 4D CT data and a motion-compensation strategy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 52, 4805–4826 (2007). 10.1088/0031-9155/52/16/007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon R., Papiez L., and Rangaraj D., “Dynamic-MLC leaf control utilizing on-flight intensity calculations: A robust method for real-time IMRT delivery over moving rigid targets,” Med. Phys. 34, 3211–3223 (2007). 10.1118/1.2750964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen P. R., Cho B., Sawant A., Ruan D., and Keall P. J., “Dynamic MLC tracking of moving targets with a single kV imager for 3D conformal and IMRT treatments,” Acta Oncol. 49, 1092–1100 (2010). 10.3109/0284186X.2010.498438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawant A., Venkat R., Srivastava V., Carlson D., Povzner S., Cattell H., and Keall P., “Management of three-dimensional intrafraction motion through real-time DMLC tracking,” Med. Phys. 35, 2050–2061 (2008). 10.1118/1.2905355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawant A., Smith R. L., Venkat R. B., Santanam L., Cho B., Poulsen P., Cattell H., Newell L. J., Parikh P., and Keall P. J., “Toward submillimeter accuracy in the management of intrafraction motion: The integration of real-time internal position monitoring and multileaf collimator target tracking,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 74, 575–582 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith R. L., Sawant A., Santanam L., Venkat R. B., Newell L. J., Cho B. C., Poulsen P., Catell H., Keall P. J., and Parikh P. J., “Integration of real-time internal electromagnetic position monitoring coupled with dynamic multileaf collimator tracking: An intensity-modulated radiation therapy feasibility study,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 74, 868–875 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tacke M. B., Nill S., Krauss A., and Oelfke U., “Real-time tumour tracking: Automatic compensation of target motion using the Siemens 160 MLC,” Med. Phys. 37, 753–761 (2010). 10.1118/1.3284543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman J., Korreman S., Persson G., Cattell H., Svatos M., Sawant A., Venkat R., Carlson D., and Keall P., “DMLC motion tracking of moving targets for intensity modulated arc therapy treatment: A feasibility study,” Acta Oncol. 48, 245–250 (2009). 10.1080/02841860802266722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Souza W. D., Malinowski K. T., Van Liew S., D’Souza G., Asbury K., McAvoy T. J., Suntharalingam M., and Regine W. F., “Investigation of motion sickness and inertial stability on a moving couch for intra-fraction motion compensation,” Acta Oncol. 48, 1198–1203 (2009). 10.3109/02841860903188668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilbert J., Meyer J., Baier K., Guckenberger M., Herrmann C., Hess R., Janka C., Ma L., Mersebach T., Richter A., Roth M., Schilling K., and Flentje M., “Tumour tracking and motion compensation with an adaptive tumour tracking system (ATTS): System description and prototype testing,” Med. Phys. 35, 3911–3921 (2008). 10.1118/1.2964090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korreman S., Medin J., and Kjaer-Kristoffersen F., “Dosimetric verification of RapidArc treatment delivery,” Acta Oncol. 48, 185–191 (2009). 10.1080/02841860802287116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otto K., “Volumetric modulated arc therapy: IMRT in a single gantry arc,” Med. Phys. 35, 310–317 (2008). 10.1118/1.2818738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popescu C. C., Olivotto I. A., Beckham W. A., Ansbacher W., Zavgorodni S., Shaffer R., Wai E. S., and Otto K., “Volumetric modulated arc therapy improves dosimetry and reduces treatment time compared to conventional intensity-modulated radiotherapy for locoregional radiotherapy of left-sided breast cancer and internal mammary nodes,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 76, 287–295 (2010). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren Q., Nishioka S., Shirato H., and Berbeco R., “Adaptive external gating based on the updating method of internal/external correlation and gating window before each beam delivery,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57, N145–N157 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/9/N145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J. Y., Yin F. F., Tenn S. E., Medin P. M., and Solberg T. D., “Use of the BrainLAB ExacTrac X-Ray 6D system in image-guided radiotherapy,” Med. Dosim. 33, 124–134 (2008). 10.1016/j.meddos.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willoughby T. R., Forbes A. R., Buchholz D., Langen K. M., Wagner T. H., Zeidan O. A., Kupelian P. A., and Meeks S. L., “Evaluation of an infrared camera and x-ray system using implanted fiducials in patients with lung tumors for gated radiation therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 66, 568–575 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho B., Poulsen P. R., and Keall P. J., “Real-time tumour tracking using sequential kV imaging combined with respiratory monitoring: A general framework applicable to commonly used IGRT systems,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 3299–3316 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/12/003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah A. P., Kupelian P. A., Waghorn B. J., Willoughby T. R., Rineer J. M., Mañon R. R., Vollenweider M. A., and Meeks S. L., “Real-time tumor tracking in the lung using an electromagnetic tracking system,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 86, 477–483 (2013). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan D., “Kernel density estimation-based real-time prediction for respiratory motion,” Phys. Med. Biol. 55, 1311–1326 (2010). 10.1088/0031-9155/55/5/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulsen P. R., Fledelius W., Cho B., and Keall P., “Image-based dynamic multileaf collimator tracking of moving targets during intensity-modulated arc therapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 83, e265–e271 (2012). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Herk M., Remeijer P., Rasch C., and Lebesque J. V., “The probability of correct target dosage: Dose-population histograms for deriving treatment margins in radiotherapy,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 47, 1121–1135 (2000). 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00518-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravkilde T., Keall P. J., Højbjerre K., Fledelius W., Worm E., and Poulsen P. R., “Geometric accuracy of dynamic MLC tracking with an implantable wired electromagnetic transponder,” Acta Oncol. 50, 944–951 (2011). 10.3109/0284186X.2011.590524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keall P. J., Cattell H., Pokhrel D., Dieterich S., Wong K. H., Murphy M. J., Vedam S. S., Wijesooriya K., and Mohan R., “Geometric accuracy of a real-time target tracking system with dynamic multileaf collimator tracking system,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 65, 1579–1584 (2006). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho B., Poulsen P. R., Sawant A., Ruan D., and Keall P. J., “Real-time target position estimation using stereoscopic kilovoltage/megavoltage imaging and external respiratory monitoring for dynamic multileaf collimator tracking,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 79, 269–278 (2011). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.ICRU, “ICRU Report 83: Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT),” J. ICRU 83, 1–106 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korreman S. S., Juhler-Nøttrup T., and Boyer A. L., “Respiratory gated beam delivery cannot facilitate margin reduction, unless combined with respiratory correlated image guidance,” Radiother. Oncol. 86, 61–68 (2008). 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]