Abstract

Plasma fibrinogen is an acute phase protein playing an important role in the blood coagulation cascade having strong associations with smoking, alcohol consumption and body mass index (BMI). Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified a variety of gene regions associated with elevated plasma fibrinogen concentrations. However, little is yet known about how associations between environmental factors and fibrinogen might be modified by genetic variation. Therefore, we conducted large-scale meta-analyses of genome-wide interaction studies to identify possible interactions of genetic variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption or BMI on fibrinogen concentration. The present study included 80,607 subjects of European ancestry from 22 studies. Genome-wide interaction analyses were performed separately in each study for about 2.6 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the 22 autosomal chromosomes. For each SNP and risk factor, we performed a linear regression under an additive genetic model including an interaction term between SNP and risk factor. Interaction estimates were meta-analysed using a fixed-effects model. No genome-wide significant interaction with smoking status, alcohol consumption or BMI was observed in the meta-analyses. The most suggestive interaction was found for smoking and rs10519203, located in the LOC123688 region on chromosome 15, with a p value of 6.2×10−8. This large genome-wide interaction study including 80,607 participants found no strong evidence of interaction between genetic variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption or BMI on fibrinogen concentrations. Further studies are needed to yield deeper insight in the interplay between environmental factors and gene variants on the regulation of fibrinogen concentrations.

Introduction

Plasma fibrinogen is an acute phase protein playing an important role in the blood coagulation cascade and is strongly associated with a variety of environmental factors such as smoking status, alcohol consumption or obesity [1]–[7]. Moreover, elevated fibrinogen concentrations indicate increased risks for developing cardiovascular diseases [8]–[10]. Genetic studies reported substantial relationships between specific genetic variants and fibrinogen concentrations [11]–[17]; the heritability of plasma fibrinogen concentrations has been estimated to range from 34% to 51% [11], [12], [18], [19]. Therefore, the regulation of fibrinogen concentrations might be seen as a complex interplay between environmental and genetic factors [20]. However, knowledge about potential interactions between environmental factors such as cardiovascular risk factors and gene variants on fibrinogen is still limited.

Smoking status, alcohol consumption and body mass index (BMI) are strong determinants of fibrinogen concentrations [1]–[7]. A large meta-analysis showed elevated fibrinogen concentrations in current smokers compared with non-smokers; moreover, fibrinogen concentrations increased with the number of cigarettes smoked per day showing a dose-related trend [7]. Similarly, elevated fibrinogen concentrations have been reported in subjects with higher BMI values [7]. For alcohol consumption, a lower mean fibrinogen concentration was observed in subjects reporting current alcohol intake compared with subjects reporting no alcohol intake [7]. All three factors represent behavioral risk factors which are easy to assess and for which we hypothesized that gene-environment interactions may modify individual risks enabling potentially targeted and individualized preventive approaches.

Several family-based and genome-wide studies have reported associations of specific gene regions with fibrinogen concentrations [11]–[17]. Recently, three large genome-wide association studies (GWAS) including as many as 90,000 participants of European origin identified up to 24 strong association signals with plasma fibrinogen concentration, among them one located in the fibrinogen β chain (FGB) gene [15]–[17]. One of these analyses [17] was essentially based on the same study population as in the present analyses.

However, little is known about whether the impact of smoking, alcohol consumption, and BMI on fibrinogen concentrations is modified by specific gene variants. Knowledge of such interactions might improve the understanding of the underlying mechanism of fibrinogen synthesis and its regulation. Two candidate-gene studies showed modifications in the association of smoking status and fibrinogen concentration by the G/A-455 polymorphism (rs1800790) located at the FGB gene [21], [22].

No genome-wide studies of effect modifications have been reported thus far for fibrinogen concentrations. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess potential gene-environment interactions (GxE) by smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI on fibrinogen concentrations, using genome-wide data from 22 studies with 80,607 subjects of European origin.

Methods

Study population

The present study was carried out within the framework of the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium which combines data from several studies of participants of European origin conducted in the United States and Europe [23]. Twenty-two studies comprising 80,607 participants provided results from their genome-wide interaction analyses for the present investigation; an overview of these studies with basic information and respective references is given in the online supporting information (S1 Methods and S1 Table) All participants provided informed consent to use their DNA for these analyses and all studies.

Fibrinogen measurements

Plasma fibrinogen concentrations were measured in 17 studies by a functional method based on the Clauss assay and in five studies by an immunonephelometric method and given in g/L [24], [25]. Fibrinogen concentrations were approximately normally distributed in all studies and therefore analysed untransformed. More details are given in the online supporting information (S1 Methods and S1 Table).

Assessment of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI

In all studies, smoking status and alcohol consumption were assessed by self-reports from study participants; assessment of BMI was based on clinical examination or self-report and described in kg/m2. For smoking status, current smokers (“smokers”) were compared with a combined group of former smokers and never-smokers (“non-smokers”). Former smokers were defined as not smoking at time of examination in 19 studies; the remaining 3 studies set a minimum cessation time before the examination which ranged between 30 days and 3 years. For alcohol consumption, coding was “0” for no alcohol consumption, “1” for alcohol consumption with less than 1 drink daily equivalent to less than 10 g alcohol per day and “2” for alcohol consumption with 1 or more drinks daily equivalent to 10 g alcohol or more per day. Information on smoking status and BMI was available in all 22 studies and on alcohol consumption in 20 studies. The assessments of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI were made at the same time as the fibrinogen measurements for all participants in all studies.

Genotyping and imputation

Genotyping was conducted separately in each study using Affymetrix or Illumina platforms and included from ∼300,000 to ∼1,000,000 genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Genotype quality control and data cleaning based on individual call rate, SNP call rate, and/or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium thresholds, and performed independently by each study.

Genotyped data were imputed in each study separately to the ∼2.6 million SNPs identified in the HapMap II Caucasian (CEU) sample from the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain [26], [27].

More details about genotyping and imputation are given in the online supporting information (S1 Methods and S2 Table).

Statistical analysis

Association of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentration

Associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentrations were assessed independently and separately in each study using linear regression. Analyses were adjusted for age (linear) and sex as well as study-specific covariates if required (see S1 Methods). Study-specific associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentration were then meta-analysed using an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect model.

Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration

Genome-wide analyses of the interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption or BMI on fibrinogen concentration were performed independently and separately in each study assuming an additive-genetic model with an additive interaction. In all studies of unrelated individuals, linear regression models with fibrinogen concentration as the outcome variable and the SNP, the risk factor under consideration, and the interaction term ‘SNP x risk factor’ were fit with adjustments for age (linear) and sex as well as study-specific covariates if required (see S1 Methods). In family-based studies, linear mixed effects models were applied to account for family correlations. Estimates of study-specific genome-wide interactions were then meta-analysed applying inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect models. To account for population stratification, study-specific test statistics were corrected using the method of genomic control [28]. SNPs with a low minor allele frequency (MAF) (<0.05) and a low imputation quality (observed to expected variance ratio <0.3) were omitted from the meta-analyses.

The meta-analyses were performed using the software METAL developed for genome-wide data [29]. To assess heterogeneity, the I2 index was computed for each interaction estimate assuming that an I2 index around 25% or below indicates no or low and around 50% moderate heterogeneity as suggested by Higgins et al [30]. Genome-wide significance of interaction was defined as a p value <5.0×10−8 for each of the three GxE analyses. Power analyses were conducted using the R (version 3.0.2) pwr package.

Results

Description of studies

The study population comprised a total of 80,607 participants of European ancestry from 22 studies. Distributions of basic characteristics are provided for each study in Table 1. Across the 22 studies, the average age ranged from 43.3 to 79.1 years and the percent of male participants ranged from 0 to 75.5%. Current smoking behaviour was reported for 6.9 to 50.3% of the participants. No alcohol consumption was reported for 5.8 to 54.9% of the participants and the mean BMI ranged from 24.3 to 28.4 kg/m2. Mean fibrinogen concentration varied from 2.67 to 3.88 g/L.

Table 1. Characteristics at the time of fibrinogen measurement by study.

| Study | Sample (N) | Age* (years) | Male sex (%) | Current smokers (%) | No alcohol consumption (%) | Alcohol consumption <10 g/day (%) | Alcohol consumption ≥10 g/day (%) | BMI (kg/m2) | Fibrinogen* (g/L) |

| ARIC | 9,256 | 54.3 (5.7) | 47.1 | 24.6 | 55.9 | 23.0 | 21.1 | 27.0 (4.8) | 2.97 (0.61) |

| B58C | 6,085 | 45.2 (0.4) | 49.7 | 23.5 | 20.3 | 39.1 | 40.6 | 27.4 (4.9) | 2.95 (0.60) |

| CARDIA | 1,435 | 45.8 (3.3) | 47.0 | 20.3 | NA | NA | NA | 25.4 (5.1) | 3.18 (0.66) |

| CHS | 3,242 | 72.3 (5.4) | 39.0 | 11.3 | 46.0 | 38.5 | 15.5 | 26.3 (4.4) | 3.15 (0.62) |

| CROATIA-Vis | 761 | 56.6 (15.5) | 41.7 | 27.9 | 43.0 | 19.2 | 37.8 | 27.1 (4.9) | 3.58 (0.82) |

| FHS | 2,797 | 54.1 (9.7) | 45.5 | 18.5 | 29.8 | 57.9 | 12.3 | 27.4 (5.0) | 3.05 (0.57) |

| HBCS | 1,728 | 61.4 (2.9) | 40.2 | 23.9 | 16.5 | 54.6 | 28.9 | 27.4 (4.5) | 3.23 (1.04) |

| InCHIANTI | 1,128 | 67.7 (15.1) | 44.9 | 19.0 | 24.5 | 30.0 | 45.5 | 27.2 (4.1) | 3.48 (0.75) |

| KORA F3 | 1,520 | 52.1 (10.2) | 49.3 | 18.0 | 29.9 | 23.6 | 46.1 | 27.2 (4.1) | 2.89 (0.66) |

| KORA F4 | 1,777 | 53.9 (8.9) | 48.9 | 20.0 | 24.5 | 29.9 | 45.6 | 27.7 (4.6) | 2.67 (0.60) |

| LBC1921 | 466 | 79.1 (0.6) | 42.1 | 6.9 | 23.2 | 56.9 | 20.0 | 26.2 (4.1) | 3.56 (0.85) |

| LBC1936 | 989 | 69.6 (0.8) | 50.8 | 12.6 | 19.2 | 40.7 | 40.0 | 27.8 (4.4) | 3.27 (0.63) |

| MARTHA | 613 | 44.1 (14.2) | 23.8 | 25.9 | NA | NA | NA | 24.3 (4.4) | 3.36 (0.68) |

| NTR | 2,343 | 47.1 (13.9) | 35.8 | 16.8 | 5.8 | 74.2 | 20.0 | 25.4 (4.0) | 2.78 (0.66) |

| ORCADES | 686 | 53.7 (15.3) | 46.6 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 59.2 | 30.0 | 27.7 (4.9) | 3.45 (0.81) |

| PROCARDIS-CL | 3,490 | 61.9 (7.0) | 75.5 | 50.3 | 37.3 | 33.7 | 29.0 | 28.4 (4.4) | 3.88 (0.86) |

| PROCARDIS-Im | 3,405 | 58.1 (8.9) | 73.5 | 33.0 | 23.9 | 36.7 | 39.4 | 27.1 (4.2) | 3.86 (1.00) |

| PROSPER | 5,244 | 75.3 (3.3) | 48.1 | 26.5 | 44.5 | 28.6 | 27.0 | 26.8 (4.2) | 3.60 (0.74) |

| RS | 2,068 | 70.4 (9.0) | 35.0 | 23.5 | 18.1 | 51.6 | 30.3 | 26.4 (3.8) | 2.81 (0.68) |

| SardiNIA | 4,691 | 43.3 (17.6) | 43.7 | 19.8 | 54.9 | 10.2 | 34.9 | 25.3 (4.7) | 3.28 (0.66) |

| SHIP | 3,807 | 48.7 (16.0) | 48.4 | 31.5 | 34.3 | 19.1 | 46.6 | 27.2 (4.8) | 2.98 (0.69) |

| WGHS | 23,076 | 54.7 (7.1) | 0 | 13.2 | 43.3 | 42.7 | 14.0 | 25.9 (5.0) | 3.59 (0.78) |

| total | 80,607 |

BMI: body mass index.

* Mean (standard deviation).

Association of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentration

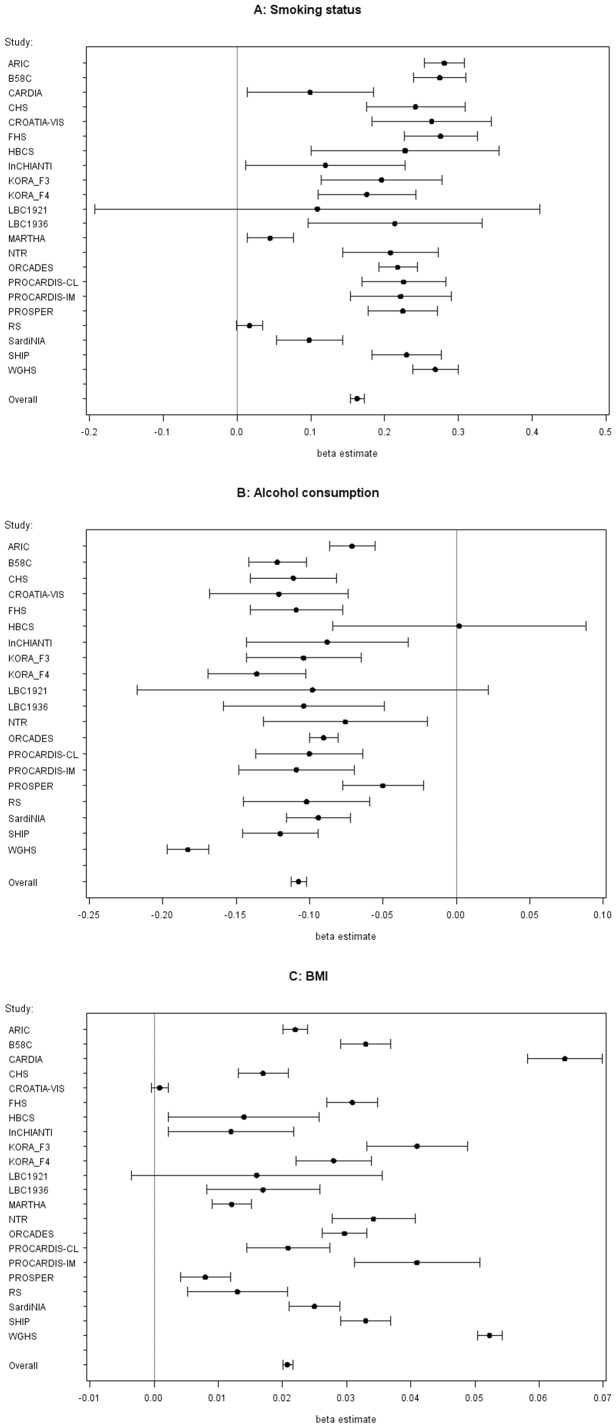

Strong significant associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with mean fibrinogen concentrations were observed in the vast majority of the 22 studies as can be seen in Fig. 1. Meta-analysis revealed mean differences in fibrinogen concentrations of 0.163 g/L (95% CI 0.154 to 0.172, 8.5×10−280) for current smokers compared with non-smokers, of -0.108 g/L (95% CI −0.113 to −0.102, 1.2×10−334) for one category increase of alcohol consumption (no, <10 g/day, ≥10 g/day), and of 0.021 g/L (95% CI 0.020 to 0.022, p value 7.1×10−691) for one kg/m2 of BMI increase.

Figure 1. Association of environmental factors with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), adjusted for age and sex.

A) Forest plot for smoking status. The beta estimate with 95% confidence intervals indicates the change in mean fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) by smoking status for each study and across all studies (“overall”, estimated by meta-analysis). B) Forest plot for alcohol consumption. The beta estimate with 95% confidence intervals indicates the change in mean fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) by alcohol consumption for each study and across all studies (“overall”, estimated by meta-analysis). Alcohol consumption was assessed only in 20 studies. C) Forest plot for BMI. The beta estimate with 95% confidence intervals indicates the change in mean fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) by BMI for each study and across all studies (“overall”, estimated by meta-analysis).

Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration – genome-wide analyses

Overall

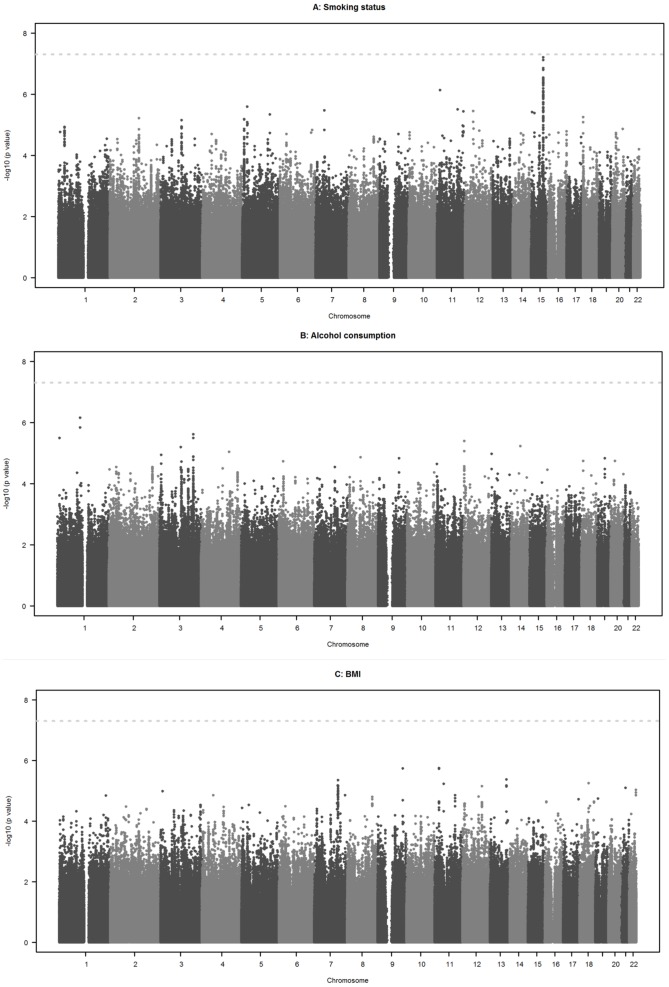

No genome-wide significant interactions with smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI were observed on fibrinogen concentration (Fig. 2). The overall genomic inflation factors from the meta-analyses were 1.0174 for interaction with smoking status, 0.9838 for interaction with alcohol consumption and 1.0075 for interaction with BMI (see QQ plots in S1 Fig.). Exclusion of studies with a genomic inflation factor >1.15 or <1/1.15 (see S3 Table) did not substantially alter these findings and revealed no genome-wide significant interactions either. The heterogeneity of interaction estimates across studies was rather weak. More than 85% of SNPs had an I2 index of 25% or less in all three interaction analyses. The upper quartile of the I2 index value distribution was 15.5% for smoking, 16.1% for alcohol consumption and 15.5% for BMI analyses.

Figure 2. Interaction of gene variants and environmental factors on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), adjusted for age and sex.

A) Manhattan plot for smoking status. The horizontal axis denotes chromosome and position of each gene variant and the vertical axis gives the negative log10 of the p value for interaction of each gene variant and smoking status on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), estimated by meta-analyses. The dotted line denotes genome-wide significance (5.0×10−8). B) Manhattan plot for alcohol consumption. The horizontal axis denotes chromosome and position of each gene variant and the vertical axis gives the negative log10 of the p value for interaction of each gene variant and alcohol consumption on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), estimated by meta-analyses. The dotted line denotes genome-wide significance (5.0×10−8). Alcohol consumption was assessed only in 20 studies. C) Manhattan plot for BMI. The horizontal axis denotes chromosome and position of each gene variant and the vertical axis gives the negative log10 of the p value for interaction of each gene variant and BMI on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), estimated by meta-analyses. The dotted line denotes genome-wide significance (5.0×10−8).

High-signal interactions

The Manhattan plot in Fig. 2 for smoking status (A) shows a peak on chromosome 15 revealing suggestive evidence of an interaction with smoking status for rs10519203, located in the LOC123688 region on chromosome 15, with a p value of 6.2×10−8 (Table 2). The difference in mean fibrinogen concentration between smokers and non-smokers was 0.048 g/L lower per copy of the A allele of rs10519203. A forest plot providing the interaction estimates with smoking status for each study and for the meta-analysis is given in S2 Fig. Heterogeneity was estimated as I2 index = 45.4% indicating a moderate level of variation of the interaction estimates across studies. The SNP rs10519203 alone was not significantly associated with fibrinogen concentration in a “G” alone analysis (p value 0.0005) performed by Sabater-Lleal et al. [17].

Table 2. Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) with lowest p value for interaction.

| Environmental factor x SNP | Chr | Position | A1* | A2 | % A1 | Beta (SE) | P value | N studies | Direction** | I2 index |

| Smoking status x rs10519203 | 15 | 76601101 | A | G | 64.8 | −0.048 (0.009) | 6.2×10−08 | 22 | ---+—+-+-------+-+--- | 45.4% |

| Alcohol consumption x rs11102001 | 1 | 110011733 | A | G | 59.0 | 0.057 (0.012) | 7.0×10−07 | 18 | ++++-++?+++-+++++?++ | 0.0% |

| BMI x rs7120820 | 11 | 21350435 | T | C | 37.6 | 0.004 (0.009) | 1.8×10−06 | 21 | ++++-++—+-+-+---++?++ | 20.2% |

BMI: body mass index, SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, Chr: chromosome, SE: standard error.

* Allele 1 is effect allele, ** The order of studies under “direction” refers to the order of studies in Table 1 .

For alcohol consumption and BMI, the lowest p values were found for rs11102001 in EPS8L3 on chromosome 1 (p value = 7.0×10−7) and rs7120820 in NELL1 on chromosome 11 (p value = 1.8×10−6), see Table 2. In both cases, weak heterogeneity was observed (I2 index≤25%).

Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration - selected candidate SNPs

The interaction of rs1800790 at the FGB locus and smoking status on fibrinogen concentration (as it was shown in two candidate-gene approach studies previously) was estimated with beta = 0.029 in the present meta-analysis (p value for interaction 0.006) indicating a 0.029 g/L higher level in mean fibrinogen concentration per A allele copy in smokers compared with non-smokers (Table 3). The I2 index of almost 60% indicated moderate heterogeneity.

Table 3. Interaction with smoking status for association with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) in SNPs with previously reported interactions (Green et al. 1993; Thomas et al. 1996) or among SNPs associated with circulating fibrinogen (Sabater-Leal et al. 2013).

| SNP | Chr | Position | A1* | A2 | % A1 | Beta (SE) | P value | N studies | Direction** | I2 index |

| Significant interaction according to Green et al. (1993) and Thomas et al. (1996): | ||||||||||

| rs1800790 | 4 | 155703158 | A | G | 23.2 | 0.029 (0.011) | 0.0062 | 22 | +++++---++-+++-++—+— | 59.2% |

| Significant SNPs according to Sabater-Leal et al. (2013): | ||||||||||

| rs1938492 | 1 | 65890417 | A | C | 62.1 | 0.017 (0.009) | 0.058 | 22 | ++-+---+-+++-+-+++—++ | 0.0% |

| rs4129267 | 1 | 152692888 | T | C | 39.1 | −0.004 (0.009) | 0.614 | 22 | +-+-+-++—+++++---++-+ | 43.9% |

| rs10157379 | 1 | 245672222 | T | C | 62.3 | 0.008 (0.009) | 0.386 | 21 | ------+++++-++++++-?++ | 0.0% |

| rs12712127 | 2 | 102093093 | A | G | 40.6 | 0.009 (0.009) | 0.286 | 22 | ++-++-++—+-++-+++++— | 0.0% |

| rs6734238 | 2 | 113557501 | A | G | 58.6 | −0.005 (0.009) | 0.561 | 22 | +---+++-+-+-+—+-+-+-+ | 0.8% |

| rs715 | 2 | 211251300 | T | C | 68.0 | −0.007 (0.011) | 0.501 | 17 | -?+?-+—?+—?+-+—+?+- | 0.7% |

| rs1476698 | 2 | 241945122 | A | G | 64.5 | 0.008 (0.009) | 0.357 | 22 | ++------+---+—++++-++ | 34.9% |

| rs1154988 | 3 | 137407881 | A | T | 78.1 | −0.013 (0.010) | 0.194 | 22 | -----+-++++---+—+-+-+ | 0.0% |

| rs16844401 | 4 | 3419450 | A | G | 7.5 | 0.017 (0.020) | 0.392 | 18 | —??+?-+++++—+++-+?-+ | 1.0% |

| rs1800789 | 4 | 155702193 | A | G | 21.1 | 0.031 (0.011) | 0.0028 | 22 | +++++---++-++—++----- | 61.1% |

| rs11242111 | 5 | 131783957 | A | G | 5.7 | 0.051 (0.033) | 0.124 | 9 | +??+?+?+?-?++?-????+?? | 30.0% |

| rs2106854 | 5 | 131797073 | T | C | 20.8 | −0.004 (0.011) | 0.737 | 22 | ---------+-+++++-+++++ | 0.0% |

| rs10226084 | 7 | 17964137 | T | C | 51.9 | −0.008 (0.009) | 0.374 | 22 | -++++---+---+-++---+— | 0.0% |

| rs2286503 | 7 | 22823131 | T | C | 36.1 | −0.013 (0.009) | 0.131 | 22 | +-+-++++++—+-+----+— | 0.0% |

| rs7464572 | 8 | 145093155 | C | G | 59.7 | −0.004 (0.009) | 0.672 | 19 | +?++----?-++?-+----+-+ | 0.0% |

| rs7896783 | 10 | 64832159 | A | G | 48.4 | −0.014 (0.008) | 0.094 | 22 | -+-++—++-----+----+— | 0.0% |

| rs1019670 | 11 | 59697175 | A | T | 35.8 | −0.009 (0.009) | 0.345 | 22 | +---++++++---+----+--- | 0.0% |

| rs7968440 | 12 | 49421008 | A | G | 64.0 | 0.003 (0.009) | 0.855 | 22 | +-+-+----+----++++—++ | 52.0% |

| rs434943 | 14 | 68383812 | A | G | 31.7 | −0.002 (0.010) | 0.884 | 21 | -----+-++++----++++?++ | 0.0% |

| rs12915708 | 15 | 48835894 | C | G | 30.6 | −0.003 (0.009) | 0.776 | 22 | -+—++---+-++----+-+— | 20.7% |

| rs7204230 | 16 | 51749832 | T | C | 69.7 | 0.008 (0.010) | 0.447 | 19 | +?-++—+?+—?-+++++-++ | 0.0% |

| rs10512597 | 17 | 70211428 | T | C | 17.9 | −0.008 (0.012) | 0.490 | 21 | ----+-+—+-+—+-+++?++ | 0.0% |

| rs4817986 | 21 | 39387382 | T | G | 27.9 | −0.025 (0.010) | 0.011 | 20 | —?+---+-----++---+?— | 12.8% |

| rs6010044 | 22 | 49448804 | A | C | 79.5 | 0.005 (0.012) | 0.669 | 21 | +—++++---++++—?-++++ | 0.0% |

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, Chr: chromosome, SE: standard error.

* Allele 1 is effect allele, ** The order of studies under “direction” refers to the order of studies in Table 1 .

Finally, we examined 24 signals previously shown to be associated with circulating fibrinogen in genome-wide analysis in almost the same study population [17] assuming a significance threshold of 0.0021 (Bonferroni correction for 24 tests: 0.05/24). None of these candidates was significant at this threshold in the present GxE meta-analyses. For smoking status, a suggestive interaction was found for rs1800789 in the FGB gene on chromosome 4 (p value for interaction 0.0028) revealing a 0.031 g/L higher difference in mean fibrinogen concentration per A allele copy in smokers compared with non-smokers (Table 3). This SNP represents almost the same signal as rs1800790 (r2 = 0.911, D′ = 1.00) for which interactions with smoking was found previously and a similar I2 index was estimated (see above).

For alcohol consumption and BMI, the lowest p values among the 24 signals were observed for rs715 in CPS1 on chromosome 2 (p value = 0.0195) and for rs10512597 in CD300LF on chromosome 17 (p value = 0.0049), see S4 and S5 Tables.

Discussion

Overall

The present study is the first to investigate interactions between smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMI and gene variants on fibrinogen concentrations based on data from genome-wide interaction studies. Meta-analysing a population of 80,607 participants of European ancestry drawn from 22 studies did not identify any variant that modified the association of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with plasma fibrinogen concentrations with genome-wide significance.

Association of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentration

Several studies have identified strong and significant associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentrations [1]–[7]. The present study confirmed these associations and is in line with findings from a large meta-analysis of 154,211 participants in 31 prospective studies conducted by the Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration (FSC) which showed comparable estimates of fibrinogen concentration differences in smokers compared to non-smokers and for differences in BMI and alcohol consumption amounts [7]. These strong associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen might be explained mainly by their relation with the acute phase reaction which contributes to the regulation of the fibrinogen synthesis [1].

Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration – genome-wide analyses

The present study found no evidence that the strong associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentrations were significantly modified by any of the approximately 2.6 million polymorphisms identified in the HapMap II Caucasian (CEU) sample. However, a peak on chromosome 15 with suggestive evidence of an interaction with smoking status was found for rs10519203 (p value for interaction 6.2×10−8) which is located in the LOC123688 region. The effect on fibrinogen level by smoking status was lower per copy of the A allele (major allele) indicating that fibrinogen regulation by tobacco exposure might be attenuated depending on the genotype of rs10519203. A strong association of genetic variants in the LOC123688 region with lung cancer has been reported recently [31]–[33]. One of these variants, rs8034191, was in complete linkage disequilibrium with rs10519203 (r2 = 1, D′ = 1). Interestingly, Truong et al. found that these variants were associated with significantly increased lung cancer risk per copy of their minor allele in former or current but not in never smokers [33].

Interaction between gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration - selected candidate SNPs

Two previous studies with a candidate-gene approach reported interactions between the G/A-455 polymorphism at the FGB gene (rs1800790) and smoking status on fibrinogen concentration in samples of healthy men; however, these studies reported contradictory findings [21], [22]: whereas, in 86 healthy men, fibrinogen concentrations were significantly higher per copy of the A allele in smokers only [21], the opposite was true in 482 healthy middle-aged men with significant associations only in non-smokers [22]. The present meta-analyses could confirm the findings of an association only in smokers [21] albeit with a sample size more than 200 times larger.

Several studies have identified strong associations of specific variants with fibrinogen levels; one of these was in the fibrinogen β chain (FBG) gene [15]–[17]. A very recently performed meta-analysis conducted also within the framework of the CHARGE consortium and comprising almost the same study population as the present investigation revealed 24 independent signals in 23 loci being significantly associated with fibrinogen concentration [17]. The present GxE meta-analyses indicated no significant modifications of the associations of smoking status, alcohol consumption and BMI with fibrinogen concentration.

Strengths and limitations

The present study was restricted to genetic variants with a minor allele frequency of at least 5%. Analyses for variants with a lower MAF produced an excess of small p values which were likely due to a poor approximation of true null distribution of the test statistics by the normal distribution. It is possible, however, that there may be significant interactions for rare variants which could be detected in studies with improved approximations or with even larger sample sizes. Moreover, the three determinants of fibrinogen were employed in commonly used categorizations across all studies; however, other definitions (e.g. never smokers versus ever smokers, other cut-off values than 10 g/day for alcohol consumption or categorized BMI) might yield significant interactions. Finally, we observed heterogeneity in covariate distribution and effect estimates which may affect our findings.

The present study is the first genome-wide interaction study aimed to detect interactions between environmental factors and gene variants on fibrinogen concentration. Its strength relies on the large numbers of studies and participants which was confirmed by a power analysis: If we assume a study population with a prevalence of exposed of ≥20% (e.g. smokers), a SNP with a MAF of ≥0.05, and an interaction of ≥0.1 meaning that the difference in mean fibrinogen concentration between exposed and non-exposed participants is at least 0.1 g/L higher per one copy of the minor allele, the power to detect an interaction would be greater than 90% based on 80,000 participants and a significance level of 5.0×10−8.These estimations indicate that the power of our study is large enough to detect genome-wide relevant interactions between SNPs and smoking, alcohol consumption and BMI on fibrinogen concentration.

Conclusions

The present large genome-wide interaction analyses including 22 studies comprising 80,607 subjects of European ancestry did not identify significant interaction of gene variants and smoking status, alcohol consumption or BMI on fibrinogen concentrations. The strong associations of these three variables with fibrinogen are not modified substantially by any of the 2.6 million common genetic variants analysed in this study. Suggestive evidence of an interaction could be found for smoking status with a fibrinogen-SNP association in smokers and but not in non-smokers. Further studies are needed to yield deeper insight in the interplay between environmental factors and functional genomics on the regulation of fibrinogen concentrations.

Supporting Information

QQ plots for interaction of gene variants and environmental factors on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), adjusted for age and sex.

(TIF)

Forest plot for interaction of rs10519203 and smoking status on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) with 95% confidence interval, adjusted for age and sex.

(TIF)

Basic information about studies.

(DOC)

Genotype information about studies.

(DOC)

Genomic inflation factor per study.

(DOC)

Interaction with alcohol consumption for association with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) among SNPs associated with circulating fibrinogen (Sabater-Leal et al. 2013).

(DOC)

Interaction with BMI for association with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) among SNPs associated with circulating fibrinogen (Sabater-Leal et al. 2013).

(DOC)

Funding statement.

(DOC)

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)

This file gives additional information about the study samples, fibrinogen measurements, genotyping/imputation and statistical analyses.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

See the supporting information file S1 Funding for the complete funding statement.

References

- 1. Krobot K, Hense HW, Cremer P, Eberle E, Keil U (1992) Determinants of plasma fibrinogen: relation to body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, smoking, alcohol, age, and sex. Results from the second MONICA Augsburg survey 1989–1990. Arterioscler Thromb 12:780–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Folsom AR (1995) Epidemiology of fibrinogen. Eur Heart J 16 Suppl A: 21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cushman M, Yanez D, Psaty BM, Fried LP, Heiss G, et al. (1996) Association of fibrinogen and coagulation factors VII and VIII with cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Health Study Investigators. Am J Epidemiol 143:665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burger M, Mensink G, Bronstrup A, Thierfelder W, Pietrzik K (2004) Alcohol consumption and its relation to cardiovascular risk factors in Germany. Eur J Clin Nutr 58:605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Shaper AG, Rumley A, Lennon L, et al. (2005) Associations between cigarette smoking, pipe/cigar smoking, and smoking cessation, and haemostatic and inflammatory markers for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 26:1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinha S, Luben RN, Welch A, Bingham S, Wareham NJ, et al. (2005) Fibrinogen and cigarette smoking in men and women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) population. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 12:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaptoge S, White IR, Thompson SG, Wood AM, Lewington S, et al. (2007) Associations of plasma fibrinogen levels with established cardiovascular disease risk factors, inflammatory markers, and other characteristics: individual participant meta-analysis of 154,211 adults in 31 prospective studies: the fibrinogen studies collaboration. Am J Epidemiol 166:867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, Lowe GD, Collins R, et al. (2005) Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA 294:1799–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Pennells L, Wood AM, White IR, et al. (2012) C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiovascular disease prediction. N Engl J Med 367:1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koenig W (2003) Fibrin(ogen) in cardiovascular disease: an update. Thromb Haemost 89:601–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Lange M, Snieder H, Ariens RA, Spector TD, Grant PJ (2001) The genetics of haemostasis: a twin study. Lancet 357:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang Q, Tofler GH, Cupples LA, Larson MG, Feng D, et al. (2003) A genome-wide search for genes affecting circulating fibrinogen levels in the Framingham Heart Study. Thromb Res 110:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kathiresan S, Yang Q, Larson MG, Camargo AL, Tofler GH, et al. (2006) Common genetic variation in five thrombosis genes and relations to plasma hemostatic protein level and cardiovascular disease risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26:1405–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacquemin B, Antoniades C, Nyberg F, Plana E, Muller M, et al. (2008) Common genetic polymorphisms and haplotypes of fibrinogen alpha, beta, and gamma chains affect fibrinogen levels and the response to proinflammatory stimulation in myocardial infarction survivors: the AIRGENE study. J Am Coll Cardiol 52:941–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danik JS, Pare G, Chasman DI, Zee RY, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. (2009) Novel loci, including those related to Crohn disease, psoriasis, and inflammation, identified in a genome-wide association study of fibrinogen in 17 686 women: the Women's Genome Health Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2:134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dehghan A, Yang Q, Peters A, Basu S, Bis JC, et al. (2009) Association of novel genetic Loci with circulating fibrinogen levels: a genome-wide association study in 6 population-based cohorts. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2:125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sabater-Lleal M, Huang J, Chasman D, Naitza S, Dehghan A, et al. (2013) Multiethnic meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >100 000 subjects identifies 23 fibrinogen-associated Loci but no strong evidence of a causal association between circulating fibrinogen and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 128:1310–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamsten A, Iselius L, de Faire U, Blomback M (1987) Genetic and cultural inheritance of plasma fibrinogen concentration. Lancet 2:988–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Souto JC, Almasy L, Borrell M, Gari M, Martinez E, et al. (2000) Genetic determinants of hemostasis phenotypes in Spanish families. Circulation 101:1546–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Maat MP (2001) Effects of diet, drugs, and genes on plasma fibrinogen levels. Ann N Y Acad Sci 936:509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green F, Hamsten A, Blomback M, Humphries S (1993) The role of beta-fibrinogen genotype in determining plasma fibrinogen levels in young survivors of myocardial infarction and healthy controls from Sweden. Thromb Haemost 70:915–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas AE, Green FR, Humphries SE (1996) Association of genetic variation at the beta-fibrinogen gene locus and plasma fibrinogen levels; interaction between allele frequency of the G/A-455 polymorphism, age and smoking. Clin Genet 50:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Psaty BM, O'Donnell CJ, Gudnason V, Lunetta KL, Folsom AR, et al. (2009) Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium: Design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from 5 cohorts. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. CLAUSS A (1957) [Rapid physiological coagulation method in determination of fibrinogen]. Acta Haematol 17:237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cremer P, Nagel D, Labrot B, Mann H, Muche R, et al. (1994) Lipoprotein Lp(a) as predictor of myocardial infarction in comparison to fibrinogen, LDL cholesterol and other risk factors: results from the prospective Gottingen Risk Incidence and Prevalence Study (GRIPS). Eur J Clin Invest 24:444–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P (2007) A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet 39:906–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR (2010) MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol 34:816–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Devlin B, Roeder K (1999) Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics 55:997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR (2010) METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26:2190–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, et al. (2008) A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 452:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu P, Vikis HG, Wang D, Lu Y, Wang Y, et al. (2008) Familial aggregation of common sequence variants on 15q24-25.1 in lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1326–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Truong T, Hung RJ, Amos CI, Wu X, Bickeboller H, et al. (2010) Replication of lung cancer susceptibility loci at chromosomes 15q25, 5p15, and 6p21: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:959–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

QQ plots for interaction of gene variants and environmental factors on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L), adjusted for age and sex.

(TIF)

Forest plot for interaction of rs10519203 and smoking status on fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) with 95% confidence interval, adjusted for age and sex.

(TIF)

Basic information about studies.

(DOC)

Genotype information about studies.

(DOC)

Genomic inflation factor per study.

(DOC)

Interaction with alcohol consumption for association with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) among SNPs associated with circulating fibrinogen (Sabater-Leal et al. 2013).

(DOC)

Interaction with BMI for association with fibrinogen concentration (in g/L) among SNPs associated with circulating fibrinogen (Sabater-Leal et al. 2013).

(DOC)

Funding statement.

(DOC)

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)

This file gives additional information about the study samples, fibrinogen measurements, genotyping/imputation and statistical analyses.

(DOC)