Abstract

Background

In bi-hormonal closed-loop systems for treatment of diabetes, glucagon sometimes fails to prevent hypoglycemia. We evaluated glucagon responses during several closed-loop studies to determine factors, such as gain factors, responsible for glucagon success and failure.

Methods

We extracted data from four closed-loop studies, examining blood glucose excursions over the 50 minutes after each glucagon dose and defining hypoglycemic failure as glucose values < 60 mg/dl. Secondly, we evaluated hyperglycemic excursions within the same period, where glucose was > 180 mg/dl. We evaluated several factors for association with rates of hypoglycemic failure or hyperglycemic excursion. These factors included age, weight, HbA1c, duration of diabetes, gender, automation of glucagon delivery, glucagon dose, proportional and derivative errors (PE and DE), insulin on board (IOB), night vs. day delivery, and point sensor accuracy.

Results

We analyzed a total of 251 glucagon deliveries during 59 closed-loop experiments performed on 48 subjects. Glucagon successfully maintained glucose within target (60 – 180 mg/dl) in 195 (78%) of instances with 40 (16%) hypoglycemic failures and 16 (6%) hyperglycemic excursions. A multivariate logistic regression model identified PE (p<0.001), DE (p<0.001), and IOB (p<0.001) as significant determinants of success in terms of avoiding hypoglycemia. Using a model of glucagon absorption and action, simulations suggested that the success rate for glucagon would be improved by giving an additional 0.8 mcg/kg.

Conclusion

We conclude that glucagon fails to prevent hypoglycemia when it is given at a low glucose threshold and when glucose is falling steeply. We also confirm that high IOB significantly increases the risk for glucagon failures. Tuning of glucagon subsystem parameters may help reduce this risk.

INTRODUCTION

While intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes is associated with improvement in the hemoglobin A1c and decreased risk of long-term complications (1,2), it increases the risk of hypoglycemia (3,4). Commercially available glucagon is effective in treating hypoglycemia (5), but it is not approved for use in preventing hypoglycemia. Additionally, the dose (1 mg) is supra-physiologic and may be associated with rebound hyperglycemia. Smaller doses of glucagon may be sufficient to treat mild or impending hypoglycemia when given manually (6,7) as well as in a closed-loop system (8).

Insulin pump therapy for type 1 diabetes has become commonplace in medicine today, with the move towards automated insulin infusion via closed-loop system being the natural next step forward (9,10). Most closed-loop systems only deliver the hormone insulin (11,12). Suspension of insulin delivery in anticipation of hypoglycemia (‘low glucose suspend’ systems, e.g. Paradigm® VeoTM) has proven quite useful for reducing hypoglycemia (13) however, the slow absorption of insulin from the subcutaneous space makes prediction of glucose trends difficult, and withholding insulin alone may not be sufficient to prevent hypoglycemia (14). Kadish first proposed dual hormone use in 1964 (15), and then more recently several investigators in the field of closed-loop systems have developed bi-hormonal systems with both insulin and glucagon (8,16-19). These studies have shown that small subcutaneous doses of glucagon help reduce the incidence and duration of hypoglycemia.

Our group uses an indirect adaptive proportional-derivative (APD) controller to calculate subcutaneous delivery rates of insulin and glucagon (20). Proportional and derivative gain factors used to determine insulin and glucagon delivery rates in the fading memory proportional derivative (FMPD) system, the precursor to the APD, were initially determined during animal studies (21). Castle et al showed that glucagon delivery using high-gain parameters (“front loading”) was more effective than low-gain parameters in reducing the frequency of hypoglycemia (8). In the ideal situation, control algorithms should calculate a sufficient glucagon dose to keep blood glucose within the normal range – not to overshoot (causing hyperglycemia) or to undershoot (failing to prevent hypoglycemia).

Additionally, there are other factors that can affect the glycemic response of glucagon (22). It is well known that glucagon is the counter-regulatory hormone to insulin, but when insulin-on-board (IOB) is high, the effect of glucagon may be blunted, or even absent altogether (14,22,23). Glucagon raises blood glucose by glycogenolysis and its response can be affected by glycogen stores in the liver. Potentially, the effect of glucagon may be blunted if the glycogen stores in the liver are low such as in fasting states.

Unlike with insulin, there are few available glucagon absorption and action models based on subcutaneous delivery (24) and one of the concerns about using glucagon in a bi-hormonal system is the antagonistic behavior between insulin and glucagon. It is possible that, if the glucagon delivery gain factors are set too high, unstable oscillation between hypo and hyperglycemia could occur. For this reason, we aim to maximize the effect of glucagon in preventing hypoglycemia while minimizing subsequent rebound hyperglycemia.

The primary aim of this paper is to elucidate factors that determine the likelihood of glucagon success when given in small doses in bi-hormonal closed-loop systems. The secondary aim is to determine the effect of the current gain factors used to calculate glucagon doses within our control algorithm on the risk of failure, and to tune the algorithm to improve the success rate.

METHODS

Studies

We extracted data from four studies performed by our group in Portland OR, looking at blood and sensor glucose excursions after doses of glucagon are given. A total of 48 subjects underwent 59 closed-loop studies. We reviewed all patient sessions, whether or not the study was completed. Subject data obtained included age, weight, diabetes duration, and HbA1c. These studies were performed at Oregon Health and Science University and Legacy hospitals (both Portland, OR) between 2009 and 2013, after receiving approval from the respective review boards (see Table 1). The algorithm used to calculate glucagon delivery was exactly the same in all studies (20), except that in the first study, glucagon doses were not scaled based on the estimated IOB. Glucagon was given via a manually controlled syringe pump (Medfusion 2001) in the first two studies, while it was automatically delivered via an insulin pump (Omnipod system, Insulet, Bedford, MA) loaded with glucagon in the last two studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the four studies reviewed. (G = glucose values 50 minutes after glucagon dose).

| Study Description | Subjects (male) | Experiments (Automated Y=yes, N=no) | Glucagon Deliveries | Successful Deliveries (60 ≤ G ≤ 180) | Hypoglycemia (G < 60) | Hyperglycemia (G > 180) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucagon vs. Placebo (GvP): a study of glucagon vs. placebo using a modified PID system (FMPD) in a closed-loop setting. | 10 (5) | 10 (N) | 54 | 47 | 4 | 3 |

| Steroid Study (SS): a study comparing the response of an adaptive system (APD) vs. FMPD to changes in insulin sensitivity with oral steroids. | 14 (9) | 25 (N) | 102 | 63 | 30 | 9 |

| In-patient Study (IP): an in-patient study of an automated version of the APD system described in (37,38) | 13 (6) | 13 (Y) | 65 | 56 | 6 | 3 |

| Out-patient Study (OP): an out-patient, hotel study using the automated APD system. | 11 (2) | 11 (Y) | 30 | 29 | 0 | 1 |

Data extraction

We evaluated all subcutaneous deliveries of glucagon during these closed-loop studies along with the glucose response. Sensor glucose was measured every 5 minutes during all four studies, while blood glucose was measured every 10 minutes during glucagon vs. placebo (GvP) and steroid studies (SS), every hour during the day and every two hours during the night for the in-patient (IP) study, and every two hours during the day and every three hours during night for the out-patient (OP) study. In this paper we analyzed sensor glucose over 50 minutes after glucagon injection to determine success or failure, and we included an assessment of the relative difference between blood and sensor glucose values whenever both were available. A window of 50 minutes was used because the APD control algorithm uses a 50-minute refractory period for glucagon after a threshold dose was delivered. This threshold dose varies from a lower limit of 0.4 mcg/kg to an upper limit of 2.0 mcg/kg, based on the current calculated IOB (up to an IOB of 20% of the subject's total daily insulin requirement), and represents the maximum allowed dose of glucagon during the last 50 minutes of closed-loop running. Failure of glucagon to prevent hypoglycemia was defined by a fall in glucose levels below 60 mg/dl during the 50-minute window, while a hyperglycemic excursion was defined as a rise in glucose levels above 180 mg/dl during the same window. A hypoglycemic failure took precedence over a hyperglycemic excursion within the 50-minute window, such that only one of the two could be defined per instance of glucagon delivery. Additionally, we separated instances of glucagon delivery based on whether a single dose was given or multiple doses were given before the refractory period was activated (multiple doses could have been given during the 50 minute period if the first glucagon delivery did not reach the maximum dose allowed within 50 minutes). The algorithm uses exponentially-decaying weighted estimates of the PE and DE over the prior 15 and 10 minutes respectively (PE weight = 0.3, DE weight = 0.4 min−1), along with preset gain factors for the error terms (PE gain = −2.7, DE gain = −0.6), to calculate glucagon doses (21). The gain factors are negative since the glucagon subsystem is activated in reverse to the insulin subsystem, i.e. when glucose is below the target, the weighted PE is negative, and when glucose is falling, the weighted DE is negative. Multiplying a negative gain factor with a negative PE or DE value would yield positive glucagon infusion rates in these circumstances, and the sum of these two components gives the raw glucagon infusion rate. These positive components of the glucagon infusion rate were utilized in this analysis, and they will be referred to as wPE and wDE for the remainder of the paper. The final rate is limited by a 50 minute refractory period that is triggered when a maximum amount of glucagon has already been delivered. The maximum amount of glucagon that can be delivered within a 50 minute period is, itself, scaled based on estimated insulin-on-board (IOB). Estimates of IOB at the time of glucagon delivery were included in the multivariate analysis. We also evaluated sensor accuracy in relation to glucagon delivery, and the relative difference (RD - based on ISO standards (25)) closest to each glucagon delivery was assessed. These values are not a measure of the sensor accuracy overall, but rather a representation of sensor discrepancy at the time of glucagon delivery. Finally, because insulin target glucose was changed between daytime (7 am to 11 pm: 115 mg/dl) and nighttime (140 mg/dl), we included day vs. night delivery as a factor that may have affected success rate.

Estimating Glucagon Effect

In an effort to better understand and simulate how altering glucagon dose could improve performance of the APD control algorithm, we simulated glucagon action by adapting both a pharmacokinetic model (24) and pharmacodynamic model (26) to predict changes in glucose over the time course of each of the 251 glucagon deliveries. The model assumed that 1) insulin effect was already accounted for in the measured glucose data, and 2) that adjusted glucose values (after applying the model of glucagon action) were not significantly affected by insulin. The same assumption was applied to non-insulin mediated glucose uptake (glucose effectiveness). In summary, the pharmacokinetic model is given by...

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

| [4] |

...where Qgg1, Qgg2, and Qgg3 are the compartments of glucagon absorption (two subcutaneous and one central compartment, respectively, with units of mg/kg); kgg1, kgg2, ke1, and ke2 are rate constants of glucagon transition through the compartments (two inter- compartment transfer constants and two elimination constants, respectively, with units of min−1); Ugg(t) is the rate of subcutaneous glucagon infusion in mg/kg/min; Gg is plasma glucagon concentration in pg/ml above the already delivered amount; and Vdgg is the volume of distribution of glucagon in ml/kg. The parmacodynamic model is given by...

| [5] |

| [6] |

...where Y is glucagon action on glucose production; SN is glucagon sensitivity; and p3 is the rate constant describing the dynamics of glucagon action (min−1), as described in Herrero et al 2012. Values of SN and p3 were averaged from published estimates. For this paper, Ggb is considered 0 since the pharmacokinetic model describes only the additional glucagon delivered, and assumptions 1) and 2) above condense equation [6] to the following...

| [7] |

...in order to determine the change in glucose by additional glucagon given. The additional change in glucose was then added to consecutive glucose values, and the new discrete glucose values were utilized in equation [7] iteratively.

Statistical analysis: Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were employed for analysis of success rates among variables due to repeated measures among separate subjects, building a multivariate model of all factors to determine odds ratios for successful glucagon delivery (family – binomial, link – logit, correlation – exchangeable, robust option on). Categorical variables were separately identified (gender, automation, nighttime delivery, and multiple dosing) within the model. Statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. Estimation of glucagon effect was performed in Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). All statistical analyses were performed using STATA-12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Across all four studies reviewed, we evaluated a total of 251 glucagon calls delivered by the pump without interruption. Glucagon was successful at both preventing hypoglycemia and not overshooting to cause rebound hyperglycemia in 195 (78%) instances. In the remaining 22% of instances, there were a total of 40 hypoglycemic failures (16% of all doses, 71% of unsuccessful events) and 16 hyperglycemic excursions (6% of all doses, 29% of all unsuccessful events). Changing the lower threshold to 70 mg/dl increased the total hypoglycemic failures to 69 events (27% of all doses, 82% of unsuccessful events).

Hypoglycemic failures

Among hypoglycemic failures at a threshold of 60 mg/dl compared to successful deliveries, univariate analysis identified a greater odds of failure with lower HbA1c (OR = 0.40, CI = 0.18 – 0.88, p = 0.024), higher glucagon dose (OR = 1.69, CI = 1.01 – 2.82, p = 0.047), single doses of glucagon (OR = 0.44 for multiple doses, CI = 0.23 – 0.86, p = 0.015), and higher wPE (OR = 1.81, CI = 1.28 – 2.55, p = 0.001). However, in a multivariable model, only wPE, higher wDE and higher IOB were found to be significantly associated with odds of failure and produced adjusted odds ratios of 3.49 (wPE), 2.73 (wDE), and 1.14 (IOB) that were all significant (p<0.001) (see Table 2). The remaining variables as outlined in table 2, when tested as a group, were not significantly associated with odds of failure (p = 0.15). Using 70 mg/dl as the hypoglycemic threshold for failures did not affect results obtained when applying the multivariable model, such that wPE, wDE, and IOB remained the only significant factors associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemic failures (p < 0.001 for all).

Table 2.

Variables included in the analysis of glucagon success rate, showing results of both univariate and multivariate analysis, expressed as odds ratios. Only the last three variables were included in the final, reduced model.

| UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS | MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Odds ratio for hypoglycemic failures | p-values | Odds ratio for hypoglycemic failures | p-values |

| Age (years) | 1.04 (0.99 – 1.08) | 0.165 | 1.03 (0.97 – 1.09) | 0.291 |

| *Sex (male) | 3.0 (0.85 – 10.55) | 0.087 | 2.54 (0.65 – 10.0) | 0.183 |

| Weight (kg) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.05) | 0.69 | 0.99 (0.94 – 1.02) | 0.460 |

| Diabetes Duration (years) | 1.04 (0.99 – 1.09) | 0.133 | 1.01 (0.96 – 1.07) | 0.617 |

| HbA1c (%) | 0.4 (0.18 – 0.88) | 0.024 | 0.48 (0.18 – 1.29) | 0.148 |

| Glucagon dose (mcg/kg) | 1.69 (1.01 – 2.82) | 0.047 | 1.45 (0.44 – 4.79) | 0.541 |

| *Automation of delivery | 0.26 (0.07 – 1.0) | 0.05 | 0.56 (0.14 – 2.5) | 0.469 |

| *Nighttime delivery | 0.76 (0.22 – 2.54) | 0.66 | 0.69 (0.23 – 2.02) | 0.495 |

| *Multiple doses | 0.44 (0.23 – 0.86) | 0.015 | 0.71 (0.34 – 1.48) | 0.364 |

| Weighted PE (per 1000 increase) | 1.81 (1.28 – 2.55) | 0.001 | 3.74 (2.27 – 6.15) †3.49 (2.26 – 5.39) |

< 0.001

† < 0.001 |

| Weighted DE (per 1000 increase) | 1.26 (0.91 – 1.77) | 0.163 | 3.23 (1.67 – 6.26) †2.73 (1.75 – 4.27) |

< 0.001

† < 0.001 |

| Insulin On Board (units) | 1.04 (1.0 – 1.09) | 0.068 | 1.10 (1.00 – 1.21) †1.14 (1.06 – 1.22) |

0.044

† < 0.001 |

Modeled as categorical variables

results from reduced multivariate model

Hyperglycemic excursions

There were only 16 deliveries where glucose exceeded 180 mg/dl, and, in both univariate analysis and the multivariate model, no factors were found to be significantly associated with greater odds of hyperglycemic excursions.

Subject Data

: There were a total of 48 subjects (45.8% male) who underwent a total of 59 experiments during these 4 studies. The average age of subjects was 41.1 ± 11.7 years, average weight was 78.1 ± 15.5 kg, average HbA1c was 7.5 ± 0.8 %, and average duration of diabetes was 20.4 ± 11.1 years. Average 24 hour glucagon dose in mcg/day was 282 ± 269 (highest 1168.5) with interquartile range of 73.75 - 444.97, and there were only a few, mild adverse events associated with glucagon delivery (nausea (6%), vomiting (2%)) that resolved without consequence.

Delivery Data

Of all glucagon instances, 147 (59%) were delivered as multiple doses before the refractory period activated, while 104 (41%) were single doses. Sensor overestimation (relative difference (RD) > 20% if BG > 75 mg/dl, difference > 15% if BG ≤ 75 mg/dl) occurred in 16 (6%) instances, with an average overestimation of 34.6 ± 14.3%, while underestimation (RD < −20% if BG > 75 mg/dl, difference < −15 mg/dl if BG ≤ 75 mg/dl) in 37 (15%) instances, with an average underestimation of −28 ± 9.2%. Nighttime delivery of glucagon occurred 41% of the time (n = 103).

Estimation of glucose response to increased glucagon doses

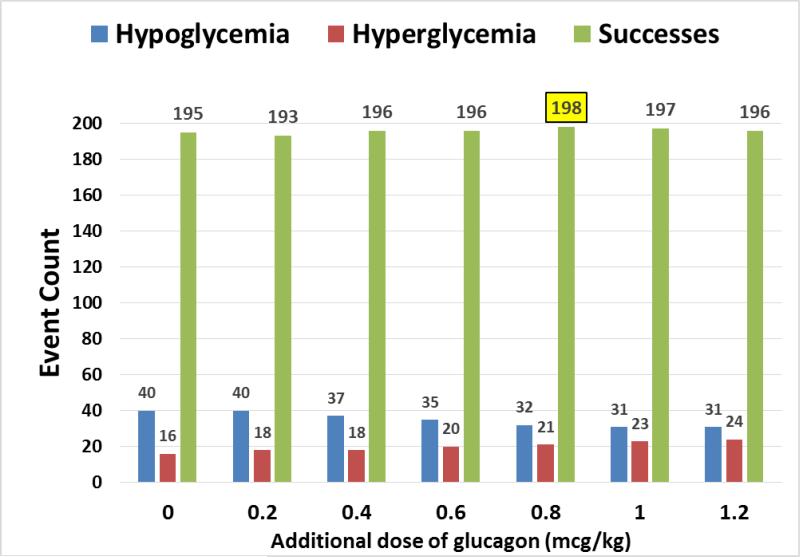

A range of additional doses were used in the model (0.2 – 1.2 mcg/kg), and the rate of hypoglycemic failures and hyperglycemic excursions were then reanalyzed after the simulations. Figure 1 shows the change in hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic occurrences after adjusting the dose of glucagon delivered by the model, as well as the proportion of successes. The increase in the total number of successes was maximized at additional doses of around 0.8 mcg/kg, above which the increase in hyperglycemic excursions outweighed the improvement in hypoglycemic failures. There were 3 more successful deliveries overall at the 0.8 mcg/kg dose.

Figure 1.

Results of simulation analysis with increasing additional doses of glucagon, showing changes in the number of successes, hypoglycemic failures, and hyperglycemic excursions.

DISCUSSION

The concept of delivering exogenous glucagon to persons with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is predicated on the fact that such individuals do not possess a normal endogenous mechanism for control of their alpha cells. In the 1970's, workers found strong evidence that the alpha cells of persons with type 1 diabetes (TID) failed to respond appropriately to hypoglycemia (27). Later, it was reported that individuals with the longest durations of T1D had the greatest degrees of glucagon deficiency (28). Taken together with other studies, this report raised the possibility that a paracrine source, namely beta cell deficiency, best explained the alpha cell differences based on diabetes duration (29). Today, though the presence of marked alpha cell dysregulation in T1D is widely accepted, the relative contribution of different causative mechanisms remains somewhat controversial. For example, Ahren and colleagues found that the degree of insulin deficiency did not predict the degree of glucagon secretory deficiency in TID (30), and that instead, perturbation of autonomic neural input to the islet may be the primary culprit (31).

Because of alpha cell dysregulation, we and others have chosen to develop methods of automatic administration of glucagon by coupling amperometric glucose sensing and subcutaneous glucagon delivery with a dual hormone control algorithm. Though delivery of small doses of glucagon usually prevents hypoglycemia, it is certainly not universally successful; the current study addresses underlying factors associated with such success and failure.

In evaluating the success rate in the four studies chosen, we observed that the rate of hypoglycemic failures after glucagon delivery was significantly associated with a more positive wPE and wDE, as well as higher IOB at the time of the glucagon call, after accounting for the effects of these individual factors. A more positive wPE occurs when glucose levels are further below the glucagon target level, suggesting that hypoglycemic failures are more likely when glucose levels are lower, as expected. Secondly, a more positive wDE occurs when glucose is falling steeply, suggesting that hypoglycemic failures are also more likely when glucose is rapidly falling. This seems logical, as rapidly falling glucose levels may not respond quickly enough to the effects of glucagon in order to prevent hypoglycemia, especially if called for at lower glucose levels (a more positive wPE). Therefore, adjusting the algorithm to call for glucagon at higher glucose levels, and when glucose is falling more rapidly may be indicated in order to prevent such failures from occurring. This could be accomplished by either raising the target for the glucagon portion of the algorithm (currently set to 95 mg/dl), and/or by adjusting the PE and DE gain factors to allow for earlier delivery of larger doses of glucagon (e.g. increasing the magnitude of the DE gain, in particular, may allow doses to be called for at a higher BG value for the same rate of fall in glucose). Because there were so few hyperglycemic excursions above 180 mg/dl, we believe glucagon doses calculated by the algorithm can be safely increased using higher gain factor magnitudes without resulting in excessive hyperglycemia, in order to reduce the incidence of hypoglycemic failures. This hypothesis is demonstrated in figure 1, where the success rate for glucagon is maximized by giving an additional 0.8 mcg/kg above the dose of glucagon already delivered.

The Oregon bi-hormonal closed-loop system performed better than its uni-hormonal counterpart to safely achieve glycemic goals in human studies (14). Additionally, some in silico comparisons have also suggested that bi-hormonal control may be superior (32). However studies also demonstrate that glucagon fails to prevent hypoglycemia 20-37% of the time (14,20). There are several factors that have been proposed to be associated with glucagon failure. Investigators have shown that high IOB could antagonize the effect of glucagon (14,22), and correction for this accounted for about 46% of failures. This has proven true in our analysis as well, since high IOB was strongly associated with hypoglycemic failures. Sensor inaccuracy is another factor suggested to be associated with glucagon failure (33,34), although in the current study, the closest available sensor error was not statistically linked to an increased risk of failure in our analysis. Additionally, commercial glucagon itself is an unstable compound, as it undergoes both physical and chemical changes over time (35,36), which could also impact upon its effectiveness when using current commercial grade preparations. Moreover, because the introduction of glucagon in closed-loop systems is a relatively new concept, there is a scarcity of literature that evaluates controller parameters used to calculate glucagon doses. In this bihormonal system, the use of glucagon is strictly limited to impending or ongoing hypoglycemia and glucagon is not delivered during hyperglycemia (a GLP-1 like effect), which minimizes the extent of insulin over-delivery and prevents wide oscillations in glucose control. At the same time, insulin infusion rates are scaled downwards for 50 minutes after glucagon delivery, to achieve the same purpose. Underestimation or overestimation of glucagon doses could potentially affect the success rate in achieving normoglycemia. Therefore tuning these controller parameters could improve the effectiveness of glucagon, as discussed. It is important to remember that tuning insulin infusion gain factors to prevent over-delivery of insulin and thus reduce hypoglycemic occurrences would be important as well, even though the focus of this paper was on the glucagon infusion subsystem. Yet still, the balance between preventing hypoglycemia and preventing hyperglycemia is difficult to maintain with slowly absorbed insulin alone, making the tuning of glucagon gain factors an important step.

The limitations of the current study include 1) its retrospective nature, 2) the fact that the control algorithm had been updated after the first study (GvP) such that glucagon delivery was scaled for insulin-on-board for the last three studies, 3) that the closest reference glucose values used to calculate the sensor accuracy in some cases were obtained a long time before the glucagon dose, and may therefore have led to an inability to detect the association between the relative difference and the rate of success in this analysis, 4) analysis was performed using sensor data (as reference blood glucose data were not sampled regularly in two of the four studies), and 5) the model of glucose dynamics in response to glucagon suggests that glucagon response is proportional to the current glucose concentration, which is not physiologically rational and may overestimate glucagon effect at high glucose values.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we provide an evaluation of factors affecting glucagon response in a bi-hormonal closed-loop system. We observed that failure of glucagon deliveries to prevent hypoglycemia occurred more frequently when glucagon is delivered while glucose is falling rapidly (high wDE) and at a lower glucose threshold (high wPE). Therefore, raising the glucagon threshold target and/or increasing gain factor magnitudes are likely to reduce hypoglycemic failures. We show that a somewhat larger glucagon dose may not incur a large hyperglycemic penalty, and can be utilized to safely prevent hypoglycemia. We also confirmed the previous assessment of high IOB as a contributing factor to glucagon failure, suggesting that insulin infusion rates should continue to be tailored according to predicted insulin effect (feedback control). We plan to evaluate new target and/or gain factors for the glucagon algorithm, utilizing an integrated model of glucagon action, which will help us determine if the changes proposed here are appropriate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript and studies included were funded by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF), NIH grant number K23DK090133, as well as by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI) grant number UL1TR000128 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Special thanks to Leon Farhy and Lv Dayu, who provided the kinetic model of glucagon absorption for use in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Castle, Dr. Jacobs, and Dr. Ward have a financial interest in Pacific Diabetes Technologies Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sustained Effect of Intensive Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus on Development and Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. JAMA} : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003 Oct;290(16):2159–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. N Engl J Med. Feb 10. 2000;342(6):381–389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumareswaran K, Evans ML, Hovorka R. Closed-loop Insulin Delivery: Towards Improved Diabetes Care. Discovery Medicine. 2012 Feb;13(69):159–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Diabetes. 1997 Feb;46(2):271–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aman J, Wranne L. Hypoglycaemia in childhood diabetes. II. Effect of subcutaneous or intramuscular injection of different doses of glucagon. Acta Paediatr Scand. Jul. 1988;77(4):548–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1988.tb10698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartley M, Thomsett MJ, Cotterill AM. Mini-dose glucagon rescue for mild hypoglycaemia in children with type 1 diabetes: the Brisbane experience. J Paediatr Child Health. Mar. 2006;42(3):108–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haymond MW, Schreiner B. Mini-dose glucagon rescue for hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. Apr. 2001;24(4):643–645. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castle JR, Engle JM, El Youssef J, Massoud RG, Yuen KC, Kagan R, et al. Novel use of glucagon in a closed-loop system for prevention of hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. Jun. 2010;33(6):1282–1287. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elleri D, Dunger DB, Hovorka R. Closed-loop insulin delivery for treatment of type 1 diabetes. BMC Med. 2011 Nov 9;9:120–7015-9-120. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hovorka R. Closed-loop insulin delivery: from bench to clinical practice. Nat Rev Endocrinol. Feb 22. 2011;7(7):385–395. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakhtiani PA, Zhao LM, El Youssef J, Castle JR, Ward WK. A review of artificial pancreas technologies with an emphasis on bi-hormonal therapy. Diabetes Obes Metab. Dec. 2013;15(12):1065–1070. doi: 10.1111/dom.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergenstal RM, Klonoff DC, Garg SK, Bode BW, Meredith M, Slover RH, et al. Threshold-based insulin-pump interruption for reduction of hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med. Jul 18. 2013;369(3):224–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg S, Brazg RL, Bailey TS, Buckingham BA, Slover RH, Klonoff DC, et al. Reduction in duration of hypoglycemia by automatic suspension of insulin delivery: the in-clinic ASPIRE study. Diabetes Technol Ther. Mar. 2012;14(3):205–209. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle JR, Engle JM, El Youssef J, Massoud RG, Ward WK. Factors influencing the effectiveness of glucagon for preventing hypoglycemia. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(6):1305–1310. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KADISH AH. Automation Control of Blood Sugar. I. a Servomechanism for Glucose Monitoring and Control. Am J Med Electron. Apr-Jun. 1964;3:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Khatib FH, Russell SJ, Nathan DM, Sutherlin RG, Damiano ER. A bihormonal closed-loop artificial pancreas for type 1 diabetes. Sci Transl Med. 2010 Apr 14;2(27):27ra27. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haidar A, Legault L, Dallaire M, Alkhateeb A, Coriati A, Messier V, et al. Glucose-responsive insulin and glucagon delivery (dual-hormone artificial pancreas) in adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized crossover controlled trial. CMAJ. 2013 Jan 28; doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Bon AC, Jonker LD, Koebrugge R, Koops R, Hoekstra JB, DeVries JH. Feasibility of a bihormonal closed-loop system to control postexercise and postprandial glucose excursions. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Sep 1. 2012;6(5):1114–1122. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Bon AC, Luijf YM, Koebrugge R, Koops R, Hoekstra JB, Devries JH. Feasibility of a Portable Bihormonal Closed-Loop System to Control Glucose Excursions at Home Under Free-Living Conditions for 48 Hours. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013 Nov 13; doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Youssef J, Castle JR, Branigan DL, Massoud RG, Breen ME, Jacobs PG, et al. A controlled study of the effectiveness of an adaptive closed-loop algorithm to minimize corticosteroid-induced stress hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Nov 1. 2011;5(6):1312–1326. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopakumaran B, Duman HM, Overholser DP, Federiuk IF, Quinn MJ, Wood MD, et al. A novel insulin delivery algorithm in rats with type 1 diabetes: the fading memory proportional-derivative method. Artif Organs. Aug. 2005;29(8):599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2005.29096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell SJ, El-Khatib FH, Nathan DM, Damiano ER. Efficacy determinants of subcutaneous microdose glucagon during closed-loop control. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Nov 1. 2010;4(6):1288–1304. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherrington AD, Chiasson JL, Liljenquist JE, Jennings AS, Keller U, Lacy WW. The role of insulin and glucagon in the regulation of basal glucose production in the postabsorptive dog. J Clin Invest. Dec. 1976;58(6):1407–1418. doi: 10.1172/JCI108596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lv D, Breton MD, Farhy LS. Pharmacokinetics modeling of exogenous glucagon in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients. Diabetes Technol Ther. Nov. 2013;15(11):935–941. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke WL, Kovatchev B. Continuous Glucose Sensors: Continuing Questions about Clinical Accuracy. J Diabetes Sci Technol. Sep. 2007;1(5):669–675. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrero P, Georgiou P, Oliver N, Johnston DG, Toumazou C. Bio-Inspired Glucose Controller Based on Pancreatic beta-Cell Physiology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. May 1. 2012;6(3):606–616. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolli GB, Dimitriadis GD, Pehling GB, Baker BA, Haymond MW, Cryer PE, et al. Abnormal glucose counterregulation after subcutaneous insulin in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. Jun 28. 1984;310(26):1706–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198406283102605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenzi M, Bohannon N, Tsalikian E, Karam JH. Duration of type I diabetes affects glucagon and glucose responses to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. West J Med. Oct. 1984;141(4):467–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flattem N, Igawa K, Shiota M, Emshwiller MG, Neal DW, Cherrington AD. Alpha- and beta-cell responses to small changes in plasma glucose in the conscious dog. Diabetes. Feb. 2001;50(2):367–375. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjoberg S, Ahren B, Bolinder J. Residual insulin secretion is not coupled to a maintained glucagon response to hypoglycaemia in long-term type 1 diabetes. J Intern Med. Oct. 2002;252(4):342–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taborsky GJ, Jr, Ahren B, Havel PJ. Autonomic mediation of glucagon secretion during hypoglycemia: implications for impaired alpha-cell responses in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. Jul. 1998;47(7):995–1005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.7.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao X, Ning H, Wang Y. Systematically in silico comparison of unihormonal and bihormonal artificial pancreas systems. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013;2013:712496. doi: 10.1155/2013/712496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward WK, Castle JR, El Youssef J. Safe glycemic management during closed-loop treatment of type 1 diabetes: the role of glucagon, use of multiple sensors, and compensation for stress hyperglycemia. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011 Nov 1;5(6):1373–1380. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward WK, Engle JM, Branigan D, El Youssef J, Massoud RG, Castle JR. The effect of rising vs. falling glucose level on amperometric glucose sensor lag and accuracy in Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011 Dec 12; doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caputo N, Castle JR, Bergstrom CP, Carroll JM, Bakhtiani PA, Jackson MA, et al. Mechanisms of glucagon degradation at alkaline pH. Peptides. Jul. 2013;45:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pedersen JS, Dikov D, Flink JL, Hjuler HA, Christiansen G, Otzen DE. The changing face of glucagon fibrillation: structural polymorphism and conformational imprinting. J Mol Biol. Jan 20. 2006;355(3):501–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobs PG, El Youssef J, Castle JR, Engle JM, Branigan DL, Johnson P, et al. Development of a fully automated closed loop artificial pancreas control system with dual pump delivery of insulin and glucagon. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:397–400. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs PG, El Youssef J, Castle J, Bakhtiani P, Branigan D, Breen M, et al. Automated control of an adaptive bi-hormonal, dual-sensor artificial pancreas and evaluation during inpatient studies. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2014 May 13; doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2323248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]