Abstract

The serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein (STRAP) was initially identified as a putative inhibitor of the canonical TGF-beta signaling pathway. Because the Smad-dependent TGF-beta pathway negatively regulates cellular growth, early functional studies suggested that STRAP behaves as an oncogene. Indeed, a correlation between STRAP overexpression and various cancers has been identified. With the emergence of new studies on the biological function of STRAP, it is becoming clear that STRAP regulates several distinct cellular processes and modulates multiple signaling pathways. While STRAP itself does not possess enzymatic activity, it appears that STRAP influences biological processes through associations with cellular proteins. In this review, we will describe the TGF-beta-dependent and -independent functions of STRAP and provide a context for the significance of STRAP activity in the development of cancer.

Keywords: STRAP, TGF-beta, Smad signaling, Cancer, Review

2. INTRODUCTION

The development of cancer is a multi-step process by which cells acquire a malignant phenotype through the accumulation of somatic mutations. While cancer progression is dependent on the disruption of many normal cellular processes, deregulation of cellular growth signals is often an early step in tumorigenesis. Previous studies on STRAP suggest that it promotes cellular proliferation and oncogenesis by blocking the anti-proliferative effects of TGF-beta (1, 2). Overexpression of STRAP has been reported in lung, colon, and breast carcinomas (1, 2), which further supports a role for STRAP as an oncogene. However, inhibition of TGF-beta signaling can not account for the full oncogenic potential of STRAP as many tumors become resistant to TGF-beta signaling through mutation of downstream effectors.

Taking the present literature into account, very little is known about STRAP. It has been determined that STRAP is a conserved 38 kDa protein that localizes to both the cytoplasm and nucleus of cells (1). Mutation of the Drosophila STRAP homologue, pterodactyl, has been implicated in tubulogenesis and branching morphogenesis defects (3). Furthermore, STRAP knockout in mice is embryonic lethal due to defects in neural tube closure, somitogenesis, and organogenesis (4). The ubiquitious expression of STRAP and requirement for normal development suggests that STRAP is important for normal cellular and physiological processes. Although STRAP itself lacks catalytic activity, analysis of its primary structure indicates that STRAP is comprised of seven WD40 domains. A common feature of the WD40 domain is its capacity for establishing protein-protein interactions and scaffolds for the formation of protein complexes (5). In recent years, studies on STRAP have led to the identification of new binding partners and functional roles. While some of these interactions can modulate TGF-beta signaling, others suggest a broader role for STRAP in cellular homeostasis and oncogenesis.

3. TGF-BETA SIGNALING

3.1. The Smad-dependent and Smad-independent TGF-beta pathways

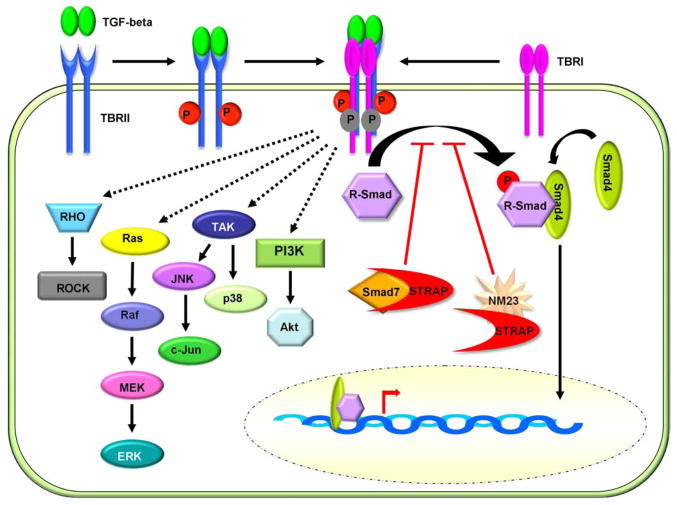

The transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) super family of proteins regulates diverse biological functions such as growth, differentiation, EMT, invasion, and apoptosis. TGF-beta signaling can be broadly subdivided into the Smad-dependent and the Smad-independent pathways (6, 7). While the signaling cascade and regulatory proteins that influence Smad signaling have been extensively characterized, little is known regarding signal transduction through the Smad-independent pathway. Signaling through both pathways is initiated by an oligomeric complex comprised of the TGF-beta receptor (TBR) I and II homodimers (Figure 1). Following receptor oligomerization and activation, TBRI propagates Smad-dependent signaling by phosphorylating the receptor associated Smads (R-Smads) -2 and -3 (8–10). Both Smads-2 and -3 contain a mad-homology 1 (MH1) domain for DNA binding and an MH2 domain that mediates interactions with TGF-beta receptors, other Smads, and transcriptional cofactors (6, 11). The activated Smad-2/Smad-3 complex then binds to the common Smad-4 (8, 10) and translocates to the nucleus where it associates with other transcriptional regulators to activate or suppress transcription from TGF-beta target genes such as p21Cip1, p15Ink4b, p16Ink4a and PAI-1 (7). Although Smad-4 contains both the MH1 and MH2 domains, Smad-4 expression may not be required for TGF-beta mediated transcription in all cell types (12). Furthermore, the specific gene expression profile induced by TGF-beta has been reported to vary according to cell type. Despite the contextual differences in TGF-beta Smad signaling, the Smad-dependent pathway is recognized as a potent suppressor of tumor formation as Smad activation is correlated with inhibition of cell cycle progression and induction of apoptosis.

Figure 1.

The TGF-beta signaling pathways. TGF-beta signaling can be propagated through Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways. In the Smad-dependent pathway, the activated TGF-beta receptor complex phosphorylates the R-Smads, Smad-2 and Smad-3. The phosphorylated R-Smads associate with the common Smad-4 and translocate to the nucleus where they function as transcriptional activators and repressors of gene expression. The inhibitory Smad, Smad-7, inhibits activation of the R-Smads by associating with TBRI. The WD40 domain protein, STRAP, also functions as an inhibitor of Smad-dependent signaling by associating with Smad-7 and TBRI. In addition to Smad activation, The TGF beta receptor complex can induce signaling through the Ras, RhoA, TAK1, and PI3K pathways. TGF-beta mediated activation of these non-Smad pathways has been associated with cellular transformation, proliferation, EMT, and migration.

In contrast to the Smad pathway, the Smad-independent pathways are believed to be important for the pro-oncogenic functions of TGF-beta. Ligand binding to TGF receptors activates MAP kinase signaling through Ras and TGF-beta activated kinase 1 (TAK1) phosphorylation as well as the RhoA and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathways. While the precise mechanism by which the activated TGF-beta receptors promote signaling through non-Smad pathways has not been determined, numerous independent studies suggest that activation of these pathways can impart malignant characteristics to normal and neoplastic cells (Figure 1). TGF-beta mediated activation of Ras has been shown to promote proliferation of cancer cells (13), and epithelial to mesechymal transition (EMT) in mammary epithelial cells (14) while activation of RhoA promotes EMT of chick heart endothelial cells (15) and migration of macrophages (16). Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway by TGF-beta has been shown to promote cell survival, EMT, and migration depending on the cell type (17–19). TGF-beta-induced activation of the p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways has also been shown to elicit biological responses favorable to cancer progression. For example, JNK activation by TGF-beta is necessary for upregulation of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), suggesting that JNK activity is important for extracellular matrix degradation and cancer cell invasion (20) (Figure 1). Furthermore, TGF-beta-induced EMT and migration of mammary epithelial cells has been reported to be dependent on p38 activation (21). Importantly, the non-Smad TGF beta pathways have also been reported to function in a concerted manner to induce specific biological responses. TAK1 and Ras can cooperate to transform epithelial cells (22) whereas activation of RhoA appears to be necessary for Ras-mediated transformation and migration (23, 24). These studies represent a small fraction of the literature pertaining to the pro-oncogenic effects of the non-Smad signaling pathways. Although the specific cellular response to TGF-beta depends on the cell type and precise genetic makeup, these reports underscore the importance of developing therapeutic compounds that can specifically block signaling through the non-Smad pathways. Several TGF-beta inhibitors are presently at various stages of pre-clinical and clinical testing for their efficacy as chemotherapeutic agents (25).

3.2. STRAP inhibits Smad-dependent TGF-beta signaling

Several proteins have been shown to negatively regulate the Smad-dependent pathway by interfering with Smad-2/3 activation. The inhibitory Smads (I-Smads) -6 and -7 block R-Smad activation through association with TBRI (26, 27) while TRIP-1 binding to TBRII has been reported to inhibit downstream transcriptional responses (28, 29). Like the I-Smads, STRAP has also been shown to inhibit Smad-dependent transcriptional activity through association with TBRI (7). Because this association was initially observed in a yeast two hybrid screen for proteins that bind to TBRI, STRAP was strongly implicated in the regulation of TGF-beta signaling. Importantly, the identification of STRAP in this study is not only the first account of STRAP in the scientific literature but also led to the first functional characterization of this protein. It was later shown that STRAP interaction with Smad-7 was required for maximum inhibition of Smad-dependent transcriptional activity (8). Additionally, STRAP has been reported to simultaneously associate with both Smad-7 and TBRI, suggesting that the STRAP/Smad-7 complex may inhibit Smad-dependent signaling by sterically blocking R-Smad binding to TBRI (30) (Figure 1).

Since many tumors develop resistance to TGF-beta due to functional inactivation of Smad proteins, it is likely that STRAP overexpression would also confer resistance to the anti-tumor effects of TGF-beta. It has already been shown that wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) exhibit a greater capacity for proliferation in the presence of TGF-beta compared to STRAP null fibroblasts (1). Furthermore, STRAP expression has been correlated with decreased TGF-beta mediated transcriptional activity in epithelial cell lines (1). The prevailing model for TGF-beta mediated carcinogenesis dictates that inactivation of the Smad tumor suppressor pathway would promote tumor formation because signal transduction events could only be propagated through the oncogenic Smad-independent pathways. Overexpression of Smad-7 has been shown to decrease Smad-dependent signaling as well as influence activation of c-Jun and Akt in response to TGF-beta (31). Moreover, overexpression of STRAP has been shown to activate the mitogen-activated ERK kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway and to downregulate p21Cip1 in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta (1). Although it has not yet been determined whether STRAP directly affects signaling through the TGF-beta Smad-independent pathways, it is possible that STRAP may affect these oncogenic pathways through cooperation with Smad-7.

4. STRAP INFLUENCES TGF-BETA AND NON-TGF-BETA PATHWAYS THROUGH INTERACTION WITH OTHER PROTEINS

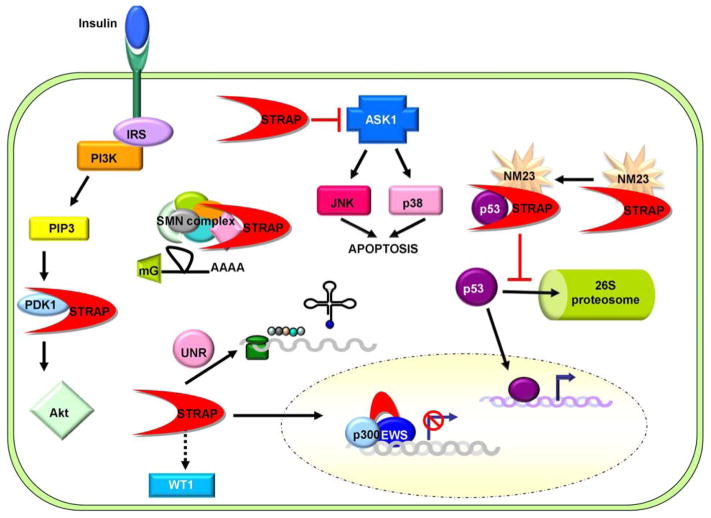

Apart from association with the core components of the Smad pathway, STRAP has also been shown to interact with various other cellular proteins (Figure 2). The functional consequences of these associations influence a wide array of cellular activities including signal transduction, transcription, translation, and protein stability. These interactions and their potential role in cancer development are discussed below.

Figure 2.

STRAP interactions influence cellular processes and signaling pathways independent of TGF-beta. The association of STRAP with cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins regulates a wide array of cellular activities such as signal transduction, gene expression, mRNA splicing, and protein synthesis. STRAP binding to PDK1 and ASK1 has been shown to increase cell survival by promoting PDK1-mediated phosphorylation of Akt and inhibiting ASK1 activation of the p38 and JNK stress pathways. STRAP has also been shown to regulate gene expression by modulating the activity of transcription factors. Ternary complex formation between STRAP, NM23, and p53 block ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p53 and increases p53 transcriptional activity. STRAP binding to the Ewing sarcoma protein, EWS, has been shown to block EWS/p300 dependent transcription. STRAP also regulates expression of mesenchymal markers by indirectly modulating WT1 activity. At the post-transcriptional level, STRAP has been implicated in the assembly of snRNPs for mRNA splicing through its association with the SMN complex. Additionally, STRAP association with unr may promote cap-independent translation of specific cellular transcripts.

4.1. STRAP promotes signaling through the PI3K pathway by associating with PDK-1

The phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) is a serine-threonine kinase that phosphorylates a wide array of signal transduction proteins including protein kinase C (PKC), S6 ribosomal kinase (S6K), p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1), and Akt. Activation of PDK1 signaling has been implicated in cellular proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion of tumor cells as well as breast cancer resistance to tamoxifen (32–36). As such, PDK1 inhibitors are currently being evaluated for their efficacy as anti-cancer drugs (37, 38).

A previous study by Seong et al. demonstrates that STRAP can bind to PDK1 and promote phosphorylation of the PDK1 substrates S6K, Akt, and Bad (39). In the same study, this association was shown to increase Smad7 binding to a constitutively active TBRI mutant and decrease TGF-beta induced transcription. It was later shown that PDK1 associates with Smads 2, 3, 4, and 7 in the absence of TGF-beta and that STRAP overexpression promotes complex formation with Smad proteins (40). Taken together, it appears that STRAP and PDK-1 binding augments the inherent functional capabilities of its binding partner. In the context of cancer progression, overexpression of PDK1 could inhibit TGF-beta mediated growth suppression by increasing STRAP and Smad7 binding to TBRI. Likewise, overexpression of STRAP may lead to persistent PDK1 activity. Given that many tumors exhibit increased activation of PI3K/PDK1 signaling, STRAP may represent a novel target for inhibition of this oncogenic signaling pathway.

4.2. The tumor suppressor NM23-H1 physically interacts with STRAP

The NM23-H1 tumor suppressor belongs to the DNA-binding nucleotide diphosphate (NDP) kinase family of proteins. NM23-H1 is regarded as a favorable prognostic indicator of poorly metastatic tumors due to its reduced expression in aggressive late stage tumors (41–43). In addition to its role as a metastasis inhibitor, NM23-H1 has also been reported to affect proliferation and differentiation of some cell lines (44, 45). Currently, the mechanism by which NM23-H1 affects these biological pathways is unknown, but efforts to identify NM23-H1 binding partners may explain the diverse functions of this protein.

With respect to the TGF-beta signaling, previous studies have shown that NM23H-1 can antagonize TGF-beta induced anchorage independent growth (42, 46). However, data describing the effects of NM23-H1 expression on TGF-beta mediated growth suppression are contradictory. Early studies suggest that NM23-H1 potentiates Smad-dependent signaling in HT29 colon cancer cells as antisense NM23 blocks TGF-beta induced growth arrest (47). Contrary to these findings, a recent study reports that NM23-H1 association with STRAP reduces transactivation of Smad-dependent reporter genes and attenuates TGF-beta mediated apoptosis and growth arrest (48). Subsequently, the NM23-H1/STRAP complex was shown to directly bind and stabilize p53 by dissociating Mdm2 (49) (Figure 2). Although transactivation of some TGF-beta responsive genes is dependent on p53 (50), the dual functions of STRAP/NM23-H1 appear to have conflicting effects on the canonical TGF-beta pathway. Like TGF-beta signaling, STRAP/NM23-H1 complex formation may yield different biological outcomes depending on the experimental context. Further investigation will be required to resolve these discrepancies.

4.3. STRAP modulates the function of Ewing Sarcoma protein

Ewing sarcoma (EWS) is a rare form of cancer originating in bone and soft tissues. The genesis of Ewing sarcoma has been attributed to chromosomal translocations that give rise to a chimeric transcript comprised of the EWSR1 gene and members of the E-twenty six (ETS) family of transcription factors (51). Currently little is known about the normal function of the wild type EWS protein. Previous studies on EWSR1 knockout mice suggest that EWS expression is required for B-cell maturation and segregation of chromosomes during meiosis (52). Structural analysis of protein domains within EWS indicates that it contains an RNA recognition motif as well as a transactivation domain that can strongly induce gene expression when fused to a gene containing a DNA binding domain (53–55).

Previous studies that focused on the identification EWS-ETS target genes suggest that the oncogenic fusion protein can function as a transcriptional activator and repressor. For example, EWS-ETS fusion proteins have been reported to repress transcription of TBRII (56) whereas the EWS-FLI protein cooperates with CBP/p300 to induce transcription of HNF4 dependent genes (57). Microarray analysis of validated EWS-FLI target genes in control and EWS silenced STA-ET-7.2 cells confirms that EWS-FLI1 can function as a direct activator and repressor of gene expression (58).

While ongoing studies aimed at identifying EWS-ETS target genes will be critical to understand the pathogenesis of Ewing sarcoma, it will also be necessary to identify proteins that can modulate EWS activity. It has been reported that STRAP can directly associate with EWS and attenuate EWS/p300 dependent activation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) reporter constructs (59) (Figure 2). HNF4 is a nuclear receptor that regulates tissue-specific differentiation and proliferation. Stable expression of HNF4 can restore a differentiated epithelial phenotype to hepatoma cells through induction of cytokeratins and E-cadherin (60). Furthermore, HNF4-alpha expression can decrease proliferation and alter cellular morphology of 293T cells (61). In the context of Ewing sarcoma, it is not yet clear whether EWS-FLI-mediated transactivation of HNF4 genes favors tumorigenesis. However, in light of the tumor suppressor functions of HNF, we predict that STRAP overexpression can confer oncogenic properties to cells that require HNF activity for maintenance of cellular differentiation and cell cycle progression.

4.4. STRAP association with ASK1 negatively regulates activation of MAPK stress pathways

The apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) is a MAPKK protein that functions as an upstream activator of the stress kinases, p38 and JNK. Under normal physiological conditions, ASK1 is maintained in an inactive state through its association with thioredoxin (Trx). Exposure to various chemicals and oxidative stress leads to its phosphorylation and dissociation from Trx. As its name suggests, ASK1 has been reported to function as a tumor suppressor due to its ability to induce apoptosis of both breast cancer and lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (62, 63).

It has recently been shown that STRAP associates with ASK1 and decreases hydrogen peroxide dependent ASK1 activation as well as ASK1 mediated apoptosis of HEK293 cells (64) (Figure 2). In light of these findings, STRAP overexpression in cancer could theoretically allow cancer cells to escape apoptosis. However, the precise biological significance of STRAP-mediated ASK1 inhibition may be more complicated. A study by Iriyama et al. suggests that ASK1 mediated apoptosis is dependent on ASK2 expression but independently promotes production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (65). Taking this study into account, the effect of STRAP on tumorigenesis may be limited to the early stages of tumor initiation; thereafter, inhibition of ASK1 could block the inflammatory processes that promote tumor progression.

5. STRAP IS INVOLVED IN MAINTAINING MESENCHYMAL MORPHOLOGY OF FIBROBLASTS

The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) refers to a process by which normal and neoplastic cells downregulate expression of junctional epithelial markers and upregulate expression of mesenchymal genes. EMT is often gauged by a morphological switch that suggests an increased capacity for cellular migration. Recently, it has been shown that STRAP knockout in mouse embryonic fibroblasts causes cells to adopt a metastable phenotype due to induction of E-cadherin. Importantly, enforced expression of STRAP in knockout MEFs abrogated E-cadherin expression and restored the mesenchymal morphology to the fibroblasts (66).

As previously mentioned, disruption of STRAP expression causes branching morphogenesis defects in Drosophila as well as defects in neural tube closure in mice (3, 4). These observed defects may point to a failure in cellular migration as coordinated migration is required for both developmental processes. Retarded motility has been confirmed in STRAP knockout MEFs in vitro suggesting a positive correlation between STRAP expression and migration (unpublished data). These findings may suggest that STRAP expression could promote EMT and metastasis of neoplastic cells but further work will be needed to illuminate the role of STRAP in migration and cancer metastasis.

6. THE ROLE OF STRAP IN mRNA SPLICING AND CAP-INDEPENDENT TRANSLATION

Unr is a cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein that has been implicated in cap-independent translation of various proteins. Previous studies aimed at identifying cellular components that initiate internal translation of rhinoviral RNA led to the isolation of a 38 kDa WD40 repeat protein complexed with unr (67). This protein, termed unrip (Unr-interacting protein), is an alias for STRAP. Although in vitro translation assays could not establish a functional role for STRAP in the initiation of viral translation, it has been reported that unrip/STRAP can function in concert with other cellular proteins to increase c-myc internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) activity (68).

The survival of motor neurons (SMN) complex is composed of multiple individual proteins that cooperate to assemble small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) for pre-mRNA splicing. The functional significance of the SMN complex is underscored by the development of spinal muscular atrophy in patients carrying homozygous mutations in the SMN1 gene. STRAP has been identified as a necessary component of the SMN complex as immunodepletion of STRAP markedly reduces snRNP assembly (69) (Figure 2). Furthermore, nuclear accumulation of the SMN complex was observed following STRAP knockdown suggesting that incorporation of STRAP is necessary for cytosolic localization (70).

At the present time, there is insufficient data on the role of STRAP in cap-independent translation to definitively state that STRAP can promote oncogenesis through modulation of protein expression. Because translation of most cellular transcripts is dependent on a 5′ cap, the effects of STRAP overexpression on protein translation would be limited to a small number of transcripts. However, given that c-myc is a recognized oncogene, STRAP may drive tumor formation by promoting c-myc overexpression. Apart from c-myc, STRAP has not been shown to regulate cap-independent translation of other proteins. This may indicate that STRAP can exhibit specificity with regards to transcript selection. Alternatively, the initial biochemical studies on Unr and STRAP activity may have lacked all of the necessary cellular components to detect an appreciable difference in translation initiation. With respect to STRAP’s function in the SMN complex, it is less clear how STRAP could promote oncogenesis. A previous study indicated that STRAP, alongside other spliceosomal proteins, is a target of small ubiquitin-related modifier 4 (SUMO4) in serum starved 293 cells (71). Despite the absence of data describing a functional consequence of sumoylation, it would be difficult to generalize any associated phenotype with cancer because SUMO4 expression is restricted to kidney, pancreatic islets, and dendritic cells (71–73). Furthermore, dysfunction of the SMN complex has only been implicated in the development of specific neuropathies suggesting that the oncogenic activity of STRAP may be achieved through other mechanisms.

7. CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE AND TARGETED INHIBITION OF STRAP

Preliminary studies suggest that STRAP overexpression may be relevant to the development of various cancers. Upregulation of STRAP has been reported in lung and colorectal tumor tissue samples analyzed by western blot and immunohistochemical staining (1). In a much larger clinical study of colorectal cancer specimens, STRAP overexpression was detected in 70.7% of specimens analyzed (74). Although there was no clinical evidence to suggest that STRAP was correlated with disease stage or survival in this study, it has been reported that STRAP amplification predicts disease outcome in response to chemotherapeutic regimens. Specifically, colorectal cancer patients whose tumors contained increased STRAP copy numbers exhibited decreased overall survival when adjuvant 5-FU therapy was administered whereas patients without STRAP amplification benefited from 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment (75). It is not yet clear why STRAP copy number affects chemotherapeutic response and survival but it is important to note that amplification of other genes on chromosome 12p was not reported in this study. Gains in chromosome regions proximal to the STRAP locus has been reported in teratomas and basal-like breast cancer so it is possible that amplification of nearby genes may also account for the observed differences in these patients (76–79).

Further work will be needed to clarify the role of STRAP in carcinogenesis, but clinical data reported thus far indicates that there is a strong association between STRAP overexpression and cancer. In vitro studies on the biological functions of STRAP suggest that it can modulate various oncogenic signaling pathways while in vivo animal studies indicate that STRAP expression promotes tumor formation (1). Taken together, it is likely that STRAP influences the pathways and processes that drive cancer progression, and should not simply be regarded as a biomarker. As such, STRAP may be relevant target for the development of anti-cancer therapeutics. At the present time, there are no reports of any STRAP inhibitors in clinical use or development. Based upon our unpublished observations, STRAP is highly stable and does not appear to be subject to regulation by growth factors. Although we can’t definitively state that STRAP expression can not be transcriptionally regulated, the absence of STRAP “inducibility” may indicate that gene amplification is the primary mechamism by which STRAP is overexpressed in cancer. Therefore, regulation of gene expression may not be a viable approach to drug design. However, like many other druggable targets, disrupting STRAP protein-protein interactions may be a useful avenue for the rational design of STRAP inhibitors. As a crystal structure for STRAP is not available yet, computational modeling programs may facilitate the identification of potential small molecule inhibitors of STRAP. Screening libraries of bioactive compounds may also lead to the identification of STRAP inhibitors. It has recently been shown that Pateamine A, a product of marine sponges, can bind to STRAP and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4A (80,81). Although the effects of Pateamine A association with STRAP have not been characterized, Pateamine A and its analogs have already been shown to block eukaryotic translation (81) and proliferation of cancer cells (82). Alternatively, intracellular single chain antibody fragments (scFvs) directed against STRAP may be a means of inhibiting STRAP association with other cellular proteins if effective tumor targeting and cellular uptake can be achieved.

8. CONCLUSION

Although STRAP is largely known as an inhibitor of classical TGF-beta signaling, it is now becoming apparent that STRAP’s biological functions are not limited to TGF-beta signaling. Compared to other cellular proteins and signaling pathways, our understanding of the complex interactions and pathways that are influenced by STRAP is still in its infancy. While recent publications illuminate new biological functions for STRAP, it has not yet been determined whether any of the STRAP protein interactions directly impact other STRAP-mediated signaling events or whether they function independently of one another. Despite the significant void of data pertaining to STRAP, the literature published by this lab and others suggests that STRAP possesses oncogenic characteristics. Moreover, the pre-clinical data that is presently available corroborates these findings. Herein, we have provided an overview of the literature on STRAP with a focus on its potential role in cancer. Future studies on this protein will be required to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms whereby STRAP promotes oncogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those colleagues whose work is not referenced because of space limitations and some of those are cited through reviews. This work was supported by R01 CA95195, CA113519, NCI SPORE grant in lung cancer (5P50CA90949, project #4), and by Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award (to P.K.D.).

Abbreviations

- STRAP

serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein

- TGF-beta

transforming growth factor-beta

- TBR

transforming growth factor-beta receptor

- BMP

bone morphogenic protein

- MH

mad homology

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- MAP kinase

mitogen activated protein kinase

- TAK1

TGF-beta activated kinase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- EMT

epithelial to mesenchymal transition

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- MEK

mitogen-activated ERK kinase

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- PDK1

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1

- PKC

protein kinase C

- S6K

S6 ribosomal kinase

- PAK1

p-21 activated kinase 1

- NDP

nucleotide diphosphate

- EWS

Ewing Sarcoma

- ETS

E-twenty six

- HNF4

hepatocyte nuclear factor 4

- ASK1

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- Trx

thioredoxin

- Unrip

Unr-interacting protein

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- SMN

survival of motor neurons

- snRNP

small nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- SUMO4

small ubiquitin-related modifier 4

- 5-FU

5-Fluorouracil

References

- 1.Halder SK, Anumanthan G, Maddula R, Mann J, Chytil A, Gonzalez AL, Washington MK, Moses HL, Beauchamp RD, Datta PK. Oncogenic function of a novel WD-domain protein, STRAP, in human carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6156–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuda S, Katsumata R, Okuda T, Yamamoto T, Miyazaki K, Senga T, Machida K, Thant AA, Nakatsugawa S, Hamaguchi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of human MAWD, a novel protein containing WD-40 repeats frequently overexpressed in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:13–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khokhar A, Chen N, Yuan JP, Li Y, Landis GN, Beaulieu G, Kaur H, Tower J. Conditional switches for extracellular matrix patterning in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;178:1283–93. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen WV, Delrow J, Corrin PD, Frazier JP, Soriano P. Identification and validation of PDGF transcriptional targets by microarray-coupled gene-trap mutagenesis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:304–12. doi: 10.1038/ng1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Roberts R. WD-repeat proteins: structure characteristics, biological function, and their involvement in human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:2085–97. doi: 10.1007/PL00000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel ME, Datta PK, Moses HL. Signal transduction by transforming growth factor-beta: a cooperative paradigm with extensive negative regulation. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1998;30–31:111–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakao A, Roijer E, Imamura T, Souchelnytskyi S, Stenman G, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. Identification of Smad2, a human Mad-related protein in the transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2896–900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagna G, Hata A, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Massague J. Partnership between DPC4 and SMAD proteins in TGF-beta signalling pathways. Nature. 1996;383:832–6. doi: 10.1038/383832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Feng X, We R, Derynck R. Receptor-associated Mad homologues synergize as effectors of the TGF-beta response. Nature. 1996;383:168–72. doi: 10.1038/383168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kretzschmar M, Massague J. SMADs: mediators and regulators of TGF-beta signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:103–11. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirard C, Kim S, Mirtsos C, Tadich P, Hoodless PA, Itie A, Maxson R, Wrana JL, Mak TW. Targeted disruption in murine cells reveals variable requirement for Smad4 in transforming growth factor beta-related signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2063–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan Z, Kim GY, Deng X, Friedman E. Transforming growth factor beta 1 induces proliferation in colon carcinoma cells by Ras-dependent, smad-independent down-regulation of p21cip1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9870–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie L, Law BK, Chytil AM, Brown KA, Aakre ME, Moses HL. Activation of the Erk pathway is required for TGF-beta1-induced EMT in vitro. Neoplasia. 2004;6:603–10. doi: 10.1593/neo.04241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavares AL, Mercado-Pimentel ME, Runyan RB, Kitten GT. TGF beta-mediated RhoA expression is necessary for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the embryonic chick heart. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1589–98. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JS, Kim JG, Moon MY, Jeon CY, Won HY, Kim HJ, Jeon YJ, Seo JY, Kim JI, Kim J, Lee JY, Kim PH, Park JB. Transforming growth factor-beta1 regulates macrophage migration via RhoA. Blood. 2006;108:1821–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-009191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SE, Xiang B, Guix M, Olivares MG, Parker J, Chung CH, Pandiella A, Arteaga CL. Transforming growth factor beta engages TACE and ErbB3 to activate phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt in ErbB2-overexpressing breast cancer and desensitizes cells to trastuzumab. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5605–20. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00787-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kattla JJ, Carew RM, Heljic M, Godson C, Brazil DP. Protein kinase B/Akt activity is involved in renal TGF-beta1-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F215–25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00548.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh YY, Chiao CC, Kuo WY, Hsiao YC, Chen YJ, Wei YY, Lai TH, Fong YC, Tang CH. TGF-beta1 increases motility and alphavbeta3 integrin up-regulation via PI3K, Akt and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue J, Sun B, Liu G, Mulder KM. Requirement of TGF-beta receptor-dependent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs)/stress-activated protein kinases (Sapks) for TGF-beta up-regulation of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:284–92. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakin AV, Safina A, Rinehart C, Daroqui C, Darbary H, Helfman DM. A critical role of tropomyosins in TGF-beta regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell motility in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4682–94. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdogan M, Pozzi A, Bhowmick N, Moses HL, Zent R. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) and TGF-beta-associated kinase 1 are required for R-Ras-mediated transformation of mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6224–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming YM, Ferguson GJ, Spender LC, Larsson J, Karlsson S, Ozanne BW, Grosse R, Inman GJ. TGF-beta-mediated activation of RhoA signalling is required for efficient (V12)HaRas and (V600E)BRAF transformation. Oncogene. 2009;28:983–93. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du J, Jiang B, Coffey RJ, Barnard J. Raf and RhoA cooperate to transform intestinal epithelial cells and induce growth resistance to transforming growth factor beta. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:233–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagaraj NS, Datta PK. Targeting the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway in human cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:77–91. doi: 10.1517/13543780903382609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Moren A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, Heuchel R, Itoh S, Kawabata M, Heldin NE, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–5. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imamura T, Takase M, Nishihara A, Oeda E, Hanai J, Kawabata M, Miyazono K. Smad6 inhibits signalling by the TGF-beta superfamily. Nature. 1997;389:622–6. doi: 10.1038/39355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choy L, Derynck R. The type II transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta receptor-interacting protein TRIP-1 acts as a modulator of the TGF-beta response. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31455–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen RH, Miettinen PJ, Maruoka EM, Choy L, Derynck R. A WD-domain protein that is associated with and phosphorylated by the type II TGF-beta receptor. Nature. 1995;377:548–52. doi: 10.1038/377548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Datta PK, Moses HL. STRAP and Smad7 synergize in the inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3157–67. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3157-3167.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halder SK, Beauchamp RD, Datta PK. Smad7 induces tumorigenicity by blocking TGF-beta-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:231–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Wang J, Wu M, Wan W, Sun R, Yang D, Sun X, Ma D, Ying G, Zhang N. Down-regulation of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 levels inhibits migration and experimental metastasis of human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:944–54. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peifer C, Alessi DR. New anti-cancer role for PDK1 inhibitors: preventing resistance to tamoxifen. Biochem J. 2009;417:e5–7. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westmoreland JJ, Wang Q, Bouzaffour M, Baker SJ, Sosa-Pineda B. Pdk1 activity controls proliferation, survival, and growth of developing pancreatic cells. Dev Biol. 2009;334:285–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi JH, Yang YR, Lee SK, Kim SH, Kim YH, Cha JY, Oh SW, Ha JR, Ryu SH, Suh PG. Potential inhibition of PDK1/Akt signaling by phenothiazines suppresses cancer cell proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1138:393–403. doi: 10.1196/annals.1414.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayascas JR, Leslie NR, Parsons R, Fleming S, Alessi DR. Hypomorphic mutation of PDK1 suppresses tumorigenesis in PTEN (+/−) mice. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1839–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Echeverria C, Sellers WR. Drug discovery approaches targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5511–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnett SF, Defeo-Jones D, Fu S, Hancock PJ, Haskell KM, Jones RE, Kahana JA, Kral AM, Leander K, Lee LL, Malinowski J, McAvoy EM, Nahas DD, Robinson RG, Huber HE. Identification and characterization of pleckstrin-homology-domain-dependent and isoenzyme-specific Akt inhibitors. Biochem J. 2005;385:399–408. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seong HA, Jung H, Choi HS, Kim KT, Ha H. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta signaling and PDK1 kinase activity by physical interaction between PDK1 and serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42897–908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seong HA, Jung H, Kim KT, Ha H. 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent PDK1 negatively regulates transforming growth factor-beta-induced signaling in a kinase-dependent manner through physical interaction with Smad proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12272–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosengard AM, Krutzsch HC, Shearn A, Biggs JR, Barker E, Margulies IM, King CR, Liotta LA, Steeg PS. Reduced Nm23/Awd protein in tumour metastasis and aberrant Drosophila development. Nature. 1989;342:177–80. doi: 10.1038/342177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leone A, Flatow U, King CR, Sandeen MA, Margulies IM, Liotta LA, Steeg PS. Reduced tumor incidence, metastatic potential, and cytokine responsiveness of nm23-transfected melanoma cells. Cell. 1991;65:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90404-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hennessy C, Henry JA, May FE, Westley BR, Angus B, Lennard TW. Expression of the antimetastatic gene nm23 in human breast cancer: an association with good prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:281–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.4.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lombardi D, Palescandolo E, Giordano A, Paggi MG. Interplay between the antimetastatic nm23 and the retinoblastoma-related Rb2/p130 genes in promoting neuronal differentiation of PC12 cells. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:470–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Lu S, Li MF, Wang ZH. Effects of tumor metastasis suppressor gene nm23-H1 on invasion and proliferation of cervical cancer cell lines. Ai Zheng. 2009;28:702–7. doi: 10.5732/cjc.008.10719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leone A, Flatow U, VanHoutte K, Steeg PS. Transfection of human nm23-H1 into the human MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cell line: effects on tumor metastatic potential, colonization and enzymatic activity. Oncogene. 1993;8:2325–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsu S, Huang F, Wang L, Banerjee S, Winawer S, Friedman E. The role of nm23 in transforming growth factor beta 1-mediated adherence and growth arrest. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:909–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seong HA, Jung H, Ha H. NM23-H1 tumor suppressor physically interacts with serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein, a transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor-interacting protein, and negatively regulates TGF-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12075–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung H, Seong HA, Ha H. NM23-H1 tumor suppressor and its interacting partner STRAP activate p53 function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35293–307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Maretto S, Insinga A, Imbriano C, Piccolo S. Links between tumor suppressors: p53 is required for TGF-beta gene responses by cooperating with Smads. Cell. 2003;113:301–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janknecht R. EWS-ETS oncoproteins: the linchpins of Ewing tumors. Gene. 2005;363:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, Watford W, Li C, Parmelee A, Bryant MA, Deng C, O’Shea J, Lee SB. Ewing sarcoma gene EWS is essential for meiosis and B lymphocyte development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1314–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI31222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.May WA, Gishizky ML, Lessnick SL, Lunsford LB, Lewis BC, Delattre O, Zucman J, Thomas G, Denny CT. Ewing sarcoma 11;22 translocation produces a chimeric transcription factor that requires the DNA-binding domain encoded by FLI1 for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5752–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.May WA, Lessnick SL, Braun BS, Klemsz M, Lewis BC, Lunsford LB, Hromas R, Denny CT. The Ewing’s sarcoma EWS/FLI-1 fusion gene encodes a more potent transcriptional activator and is a more powerful transforming gene than FLI-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7393–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ohno T, Rao VN, Reddy ES. EWS/Fli-1 chimeric protein is a transcriptional activator. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5859–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hahm KB, Cho K, Lee C, Im YH, Chang J, Choi SG, Sorensen PH, Thiele CJ, Kim SJ. Repression of the gene encoding the TGF-beta type II receptor is a major target of the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. Nat Genet. 1999;23:222–7. doi: 10.1038/13854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Araya N, Hirota K, Shimamoto Y, Miyagishi M, Yoshida E, Ishida J, Kaneko S, Kaneko M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A. Cooperative interaction of EWS with CREB-binding protein selectively activates hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5427–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siligan C, Ban J, Bachmaier R, Spahn L, Kreppel M, Schaefer KL, Poremba C, Aryee DN, Kovar H. EWS-FLI1 target genes recovered from Ewing’s sarcoma chromatin. Oncogene. 2005;24:2512–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anumanthan G, Halder SK, Friedman DB, Datta PK. Oncogenic serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein modulates the function of Ewing sarcoma protein through a novel mechanism. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10824–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spath GF, Weiss MC. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 provokes expression of epithelial marker genes, acting as a morphogen in dedifferentiated hepatoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:935–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lucas B, Grigo K, Erdmann S, Lausen J, Klein-Hitpass L, Ryffel GU. HNF4alpha reduces proliferation of kidney cells and affects genes deregulated in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:6418–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meurette O, Stylianou S, Rock R, Collu GM, Gilmore AP, Brennan K. Notch activation induces Akt signaling via an autocrine loop to prevent apoptosis in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5015–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuo CT, Chen BC, Yu CC, Weng CM, Hsu MJ, Chen CC, Chen MC, Teng CM, Pan SL, Bien MY, Shih CH, Lin CH. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 mediates denbinobin-induced apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:43. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jung H, Seong HA, Manoharan R, Ha H. Serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein (STRAP) inhibits apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 function through direct interaction. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iriyama T, Takeda K, Nakamura H, Morimoto Y, Kuroiwa T, Mizukami J, Umeda T, Noguchi T, Naguro I, Nishitoh H, Saegusa K, Tobiume K, Homma T, Shimada Y, Tsuda H, Aiko S, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Chida K, Kamei Y, Kozuma S, Taketani Y, Matsuzawa A, Ichijo H. ASK1 and ASK2 differentially regulate the counteracting roles of apoptosis and inflammation in tumorigenesis. Embo J. 2009;28:843–53. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kashikar ND, Reiner J, Datta A, Datta PK. Serine threonine receptor-associated protein (STRAP) plays a role in the maintenance of mesenchymal morphology. Cell Signal. 2009;22:138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hunt SL, Hsuan JJ, Totty N, Jackson RJ. unr, a cellular cytoplasmic RNA-binding protein with five cold-shock domains, is required for internal initiation of translation of human rhinovirus RNA. Genes Dev. 1999;13:437–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evans JR, Mitchell SA, Spriggs KA, Ostrowski J, Bomsztyk K, Ostarek D, Willis AE. Members of the poly (rC) binding protein family stimulate the activity of the c-myc internal ribosome entry segmentin vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 2003;22:8012–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carissimi C, Baccon J, Straccia M, Chiarella P, Maiolica A, Sawyer A, Rappsilber J, Pellizzoni L. Unrip is a component of SMN complexes active in snRNP assembly. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2348–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grimmler M, Otter S, Peter C, Muller F, Chari A, Fischer U. Unrip, a factor implicated in cap-independent translation, associates with the cytosolic SMN complex and influences its intracellular localization. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3099–111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo D, Han J, Adam BL, Colburn NH, Wang MH, Dong Z, Eizirik DL, She JX, Wang CY. Proteomic analysis of SUMO4 substrates in HEK293 cells under serum starvation-induced stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:1308–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo D, Li M, Zhang Y, Yang P, Eckenrode S, Hopkins D, Zheng W, Purohit S, Podolsky RH, Muir A, Wang J, Dong Z, Brusko T, Atkinson M, Pozzilli P, Zeidler A, Raffel LJ, Jacob CO, Park Y, Serrano-Rios M, Larrad MT, Zhang Z, Garchon HJ, Bach JF, Rotter JI, She JX, Wang CY. A functional variant of SUMO4, a new I kappa B alpha modifier, is associated with type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2004;36:837–41. doi: 10.1038/ng1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bohren KM, Nadkarni V, Song JH, Gabbay KH, Owerbach D. A M55V polymorphism in a novel SUMO gene (SUMO-4) differentially activates heat shock transcription factors and is associated with susceptibility to type I diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27233–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim CJ, Choi BJ, Song JH, Park YK, Cho YG, Nam SW, Yoo NJ, Lee JY, Park WS. Overexpression of serine-threonine receptor kinase-associated protein in colorectal cancers. Pathol Int. 2007;57:178–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buess M, Terracciano L, Reuter J, Ballabeni P, Boulay JL, Laffer U, Metzger U, Herrmann R, Rochlitz C. STRAP is a strong predictive marker of adjuvant chemotherapy benefit in colorectal cancer. Neoplasia. 2004;6:813–20. doi: 10.1593/neo.04307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Moreno-Bueno G, Tan DS, Marchio C, Vatcheva R, Rayter S, Mahler-Araujo B, Fulford LG, Hungermann D, Mackay A, Grigoriadis A, Fenwick K, Tamber N, Hardisson D, Tutt A, Palacios J, Lord CJ, Buerger H, Ashworth A, Reis-Filho JS. Tiling path genomic profiling of grade 3 invasive ductal breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2711–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han W, Jung EM, Cho J, Lee JW, Hwang KT, Yang SJ, Kang JJ, Bae JY, Jeon YK, Park IA, Nicolau M, Jeffrey SS, Noh DY. DNA copy number alterations and expression of relevant genes in triple-negative breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:490–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poulos C, Cheng L, Zhang S, Gersell DJ, Ulbright TM. Analysis of ovarian teratomas for isochromosome 12p: evidence supporting a dual histogenetic pathway for teratomatous elements. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:766–71. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Henegariu O, Vance GH, Heiber D, Pera M, Heerema NA. Triple-color FISH analysis of 12p amplification in testicular germ-cell tumors using 12p band-specific painting probes. J Mol Med. 1998;76:648–55. doi: 10.1007/s001090050262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Rzasa RM, Shea HA, Li S, Park K, Ma G, Romo D, Liu JO. Isolation and identification of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A as a molecular target for the marine natural product Pateamine A. Methods Enzymol. 2007;431:303–24. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Low WK, Dang Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, Shi Z, Choi NS, Merrick WC, Romo D, Liu JO. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:709–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuznetsov G, Xu Q, Rudolph-Owen L, Tendyke K, Liu J, Towle M, Zhao N, Marsh J, Agoulnik S, Twine N, Parent L, Chen Z, Shie JL, Jiang Y, Zhang H, Du H, Boivin R, Wang Y, Romo D, Littlefield BA. Potent in vitro and in vivo anticancer activities of des-methyl, des-amino pateamine A, a synthetic analogue of marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]