Abstract

Purpose

Describe prevalence and relationships to cardiovascular morbidity of depression, anxiety and medication use among Hispanic/Latinos of different ethnic backgrounds.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis of 15,864 men and women ages 18–74 in the population-based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed with shortened Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale and Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale.

Results

Prevalence of high depressive symptoms ranged from low of 22.3% (95%CI: 20.4–24.3) to high of 38.0% (95%CI: 35.2–41.0) among those of Mexican or Puerto Rican background respectively. Adjusted odds ratios for depression rose monotonically with number of CVD risk factors from 1.46 (95%CI: 1.18, 1.75) for those with no risk factors to 4.36 (95%CI: 2.47, 7.70) for those with 5 risk factors. Antidepressant medication was used by 5% with striking differences between those with and without history of CVD (15.4% and 4.6% respectively) and between insured (8.2%) and uninsured (1.8%).

Conclusions

Among US Hispanics/Latinos, high depression and anxiety symptoms varied nearly twofold by Hispanic background and sex, history of CVD and increasing number of CVD risk factors. Antidepressant medication use was lower than in the general population, suggesting under treatment especially among those who had no health insurance.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, Hispanics, Latinos, ethnic differences, antidepressants, antianxiety medications, HCHS/SOL, cardiovascular risk

INTRODUCTION

Depressive symptoms, depressed mood or subclinical depression, as well as anxiety, assessed with screening instruments has been associated with higher risks of heart disease, stroke and all-cause mortality 1–3,4. There is a bidirectional relationship between depression and cardiovascular disease (CVD), with depression being common post myocardial infarction (MI)5 and post stroke6.

While the study by Alegria and colleagues7 from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS), examined a probability sample of 2,554 persons from four background groups: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans and “other” it did not distinguish those of Dominican, South American or Central American backgrounds. Another important study from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) looked only at Mexican, Puerto Rican and Cuban background groups. Little research exists on use of anti-depression and anti-anxiety medications in these diverse groups. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), the largest, most comprehensive study of the health of Hispanics/Latinos from 6 different national backgrounds, consists of a probability sample of 16,415 Hispanic/Latino persons ages 18–74 in four different communities across the Unites States. HCHS/SOL provides a unique opportunity to examine depressive and anxiety symptomatology, and use of antidepressant and anti-anxiety medications in Hispanic/Latino groups of different national backgrounds, by age, sex and in relation to CVD and risk factors for CVD.

METHODS

Design Overview, Setting and Participants

The HCHS/SOL enrolled 16,415 self-identified Hispanic/Latino participants ages 18–74 in four defined communities in the US: Bronx, New York; San Diego, California; Miami, Florida; and Chicago, Illinois, to describe and study prospectively health and disease in Hispanic/Latinos from diverse origins, including Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Cuban, Central American and South American. The cohort was selected and enrolled between 2008–2011 through stratified multi-stage area probability sample of the four diverse regions, each with high concentrations of specific Hispanic/Latino backgrounds, allowing estimation of prevalence rates of diseases and risk factors for each background. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Details of the design, recruitment and implementation of HCHS/SOL have been published elsewhere8, 9.

During their baseline visit, participants completed questionnaires according to their language preference, in English or Spanish, that included information on demographic, behavioral, psychosocial and physiological factors, co-morbidities, dietary and medications information, cognitive scales and assessment of depression, anxiety and acculturation. A blood draw, glucose tolerance test, blood pressure and other physical measurements were completed.

Measurements

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 10-item form of Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CES-D1010. This scale is a subset of the original 20-item CES-D scale11 asking how often the respondent has experienced a symptom in the past week. Response categories range from “none of the time” to “most of the time”; On the full 20-item scale a cut-point of ≥ 16, out of a possible high of 60, indicates presence of significant depressive symptoms validated using the DSM-III criteria for clinical depression. For the shortened CES-D10 scale used here, the cut-point ≥10 (out of a possible high of 30) has generally been used for screening purposes12–14. When measured against the ≥16 cut-point for the CES-D20 among 88 older adults, the CES-D10 cut point of ≥10 had sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 100%10. In another study of adults 60 – 74 years, The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP), among 4613 men and women, the cut-point of ≥10 on the CES-D10 showed a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 98% against the CES-D20 cut point of ≥16, and the correlation between the CES-D10 and the CES-D20 was 0.96 (unpublished data available). In our study we use a cut-point of ≥ 10 on the CES-D10 to denote high levels of depressive symptoms, which may reflect clinical depression or dysphoria but is not equivalent to a clinical diagnosis of major depression. Persons scoring above the cut-point should be considered for clinical evaluation by a mental health professional. In this article we may use the term “depression” to denote high depressive symptoms, at or above the cut-point.

Anxiety was assessed by the shortened Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale (STAS) that uses 10 items from the 20-item Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale, that measures proneness to be anxious. Respondents answer how they generally feel, with questions such as: “I feel nervous and restless”, with responses of “almost never”, “sometimes”, “often” or “almost always”. Summary scores range from 10 to 40. There is no established cut-point for this scale and therefore we summarize the continuous data using means and confidence intervals.

Psychometric analyses were performed (available on request) to evaluate the internal consistency and the factor structure of the CES-D10 and the STAS in the HCHS/SOL cohort. In addition, multiple group confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted to examine the configural invariance (or equivalence) of these measures across English and Spanish speakers. Configural invariance exists when the number of factors and the items that load on each factor are the same across language. The scores for the CES-D10 and STAS exceeded the traditional threshold for internal consistency (CES-D10: αfull sample = .82; αEnglish = .82; αSpanish = .82; STAS: αfull sample = .93; αEnglish = .92; αSpanish = .94), indicating acceptable reliability for both scales and all Hispanic national groups. A one-factor CFA model fit well according to descriptive fit indices in both scales. Multi-group analyses showed the one-factor structure of the CES-D 10 and STAS to be invariant across language. Therefore, items on the CES-D 10 and STAS perform similarly in English and Spanish, thus suggesting that the same construct is being measured in each language group. These psychometric analyses demonstrated evidence of internal consistency for both languages and all national background groups, factorial validity, factorial invariance across language versions, and construct validity (in the form of theoretically consistent patterns of correlations with related Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and STAS).

Medication use was determined from pill bottles brought by the participant to the clinic visit where the label data were scanned into a computer and matched to a Medical Therapeutic Classification (MTC), or the National Drug Code (NDC). If manual coding was necessary, this was done centrally at the Coordinating Center.

Covariate definitions

We consider burden of risk factors for CVD as the number of the following 5 risk factors: hypertension (systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or being on current antihypertensive medications as determined from scanned medication labels); diabetes (fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C ≥ 6.5%, or current use of diabetes medications); dyslipidemia (LDL cholesterol ≥160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol ≤ 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides ≥200 mg/dL); current smoking; obesity (BMI ≥ 30). Burden may range from 0 to 5 risk factors. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is defined as CHD including self-reported myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass surgery, and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), or stroke. We also considered separately MI, stroke and revascularization without MI.

Statistical Analysis

Of 16,415 enrolled men and women, 15,864 (97%) completed all questions on the depression and anxiety scales, and they comprise our analytic cohort. We present actual cohort sample sizes in demographic subgroups; however, weighted estimates of prevalence, means, confidence intervals, and odds ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals are presented that correctly account for the probability sampling design which included stratification, cluster sampling, and over-sampling of individuals aged 45–74 years.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence limits from logistic regression are presented, with CES-D above the cut-point ≥ 10 as the dependent variable in unadjusted models, in minimally adjusted models for age, sex, clinical site and Hispanic/Latino background and in models additionally adjusted for marital status, education, current smoking, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and self-report of prior coronary heart disease or stroke. We present nominal P values, not accounting for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

The self-reported background of the analytic cohort is 40% Mexican, 16% Puerto Rican,14% Cuban, 11% Central American, 9% Dominican, and 7% South American. Women comprised 60%; the vast majority was not born in the 50 United Sates (83%) with the greatest proportion immigrating as young adults (ages 20–44). Spanish was the preferred language for questionnaires completion for 80.1% of the analytic cohort. The description of the analytic cohort shows raw percentages of actual participants thatdo not account for probability sampling; all further results, except for the subgroup n’s, are weighted to account for probability sampling.

Prevalence and demographic correlates of depression

The overall prevalence of depression was 27.0% (95% CI 25.8–28.2), with low of 22.3% (95% CI 20.4 – 24.3) and high of 38.0% (95% CI 35.2 – 41.0) among those of Mexican or Puerto Rican background respectively (Table 1). Within Hispanic/Latino national background groups, there were no or small differences by site; Puerto Ricans had the highest rates both in the Bronx or Chicago (data not shown). Higher prevalence was seen in women than in men, in those with less than a high school education, and in those ages 45–64.

Table 1.

Depressive symptomatology on CES-D10 by demographic and nativity characteristics.

| Depression score (CES-D10) | Depression, ≥ 10 CES-D10 | Odds ratios for high depressive symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Prevalence | Model 1* | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| N | Mean (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 15864 | 7.0 (6.8, 7.1) | 27.0 (25.8, 28.2) | - | - | - |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Hispanic/LatinoBackground‡ | ||||||

| Mexican | 6378 | 6.3 (6.1, 6.6) | 22.3 (20.4, 24.3) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dominican | 1396 | 7.1 (6.7, 7.5) | 27.4 (24.6, 30.4) | 1.30 (1.08, 1.57) | 0.88 (0.64, 1.20) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.25) |

| Central American | 1684 | 6.6 (6.2, 6.9) | 24.9 (22.4, 27.5) | 1.16 (0.97, 1.38) | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 1.08 (0.85, 1.38) |

| Cuban | 2265 | 6.9 (6.5, 7.2) | 27.9 (25.6, 30.4) | 1.36 (1.16, 1.61) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | 1.44 (1.11, 1.85) |

| Puerto Rican | 2603 | 8.8 (8.3, 9.2) | 38.0 (35.2, 41.0) | 2.15 (1.82, 2.54) | 1.62 (1.25, 2.10) | 1.54 (1.20, 1.98) |

| South American | 1039 | 6.5 (6.0, 6.9) | 24.2 (20.9, 27.7) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | 0.96 (0.74, 1.26) | 1.12 (0.85, 1.46) |

| Sex‡ | ||||||

| Men | 6356 | 6.0 (5.8, 6.2) | 20.7 (19.2, 22.2) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Women | 9508 | 7.9 (7.7, 8.1) | 32.8 (31.3, 34.4) | 1.86 (1.66, 2.08) | 1.90 (1.70, 2.13) | 2.01 (1.79, 2.26) |

| Age Group‡ | ||||||

| 18–44 | 6488 | 6.6 (6.4, 6.8) | 24.0 (22.5, 25.5) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 45–64 | 8103 | 7.7 (7.5, 8.0) | 32.1 (30.5, 33.7) | 1.50 (1.35, 1.67) | 1.45 (1.30, 1.60) | 1.20 (1.07, 1.35) |

| 65–74 | 1273 | 7.0 (6.5, 7.5) | 29.4 (26.0, 33.1) | 1.36 (1.12, 1.64) | 1.23 (1.01, 1.50) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.07) |

| Education‡ | ||||||

| >HS | 5611 | 6.3 (6.0, 6.5) | 22.5 (20.8, 24.3) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| HS or equivalent | 4030 | 6.9 (6.6, 7.2) | 26.6 (24.5, 28.8) | 1.25 (1.08, 1.44) | 1.35 (1.16, 1.56) | 1.33 (1.15, 1.54) |

| <HS | 5906 | 7.9 (7.6, 8.2) | 32.9 (31.0, 34.9) | 1.69 (1.49, 1.93) | 1.71 (1.49, 1.96) | 1.65 (1.44, 1.89) |

| Marital Status‡ | ||||||

| Married/Living with a partner | 8221 | 6.3 (6.1, 6.5) | 23.1 (21.7, 24.6) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Single | 4350 | 7.3 (7.0, 7.5) | 28.5 (26.6, 30.5) | 1.30 (1.15, 1.47) | 1.31 (1.15, 1.49) | 1.33 (1.17, 1.51) |

| Divorced | 2605 | 8.3 (8.0, 8.7) | 35.4 (32.9, 38.0) | 1.86 (1.63, 2.11) | 1.50 (1.32, 1.72) | 1.52 (1.33, 1.74) |

| Widowed | 657 | 8.6 (7.3, 9.9) | 36.6 (29.7, 44.0) | 1.86 (1.34, 2.57) | 1.23 (0.90, 1.68) | 1.13 (0.84, 1.53) |

| Acculturation-related Variables | ||||||

| Nativity† | ||||||

| Foreign Born | 13089 | 6.8 (6.7, 7.0) | 26.4 (25.2, 27.6) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| U.S. Born | 2760 | 7.4 (7.0, 7.7) | 29.1 (26.6, 31.8) | 1.14 (0.99, 1.30) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.40) | 1.19 (1.01, 1.41) |

| Interview language†a | ||||||

| Spanish | 12707 | 6.8 (6.6, 7.0) | 26.4 (25.1, 27.7) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| English | 3157 | 7.5 (7.2, 7.8) | 28.9 (26.6, 31.3) | 1.12 (0.98, 1.27) | 1.03 (0.89, 1.19) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.23) |

| Immigrant Generation† | ||||||

| First | 12837 | 6.8 (6.7, 7.0) | 26.3 (25.1, 27.6) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Second | 2992 | 7.4 (7.0, 7.7) | 29.0 (26.7, 31.5) | 1.14 (1.00, 1.29) | 1.20 (1.04, 1.38) | 1.19 (1.03, 1.38) |

| Age at immigration† | ||||||

| U.S. Born | 2760 | 7.4 (7.0, 7.7) | 29.1 (26.6, 31.8) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Child (0–12) | 1409 | 7.3 (6.8, 7.8) | 28.0 (24.7, 31.7) | 0.94 (0.75, 1.17) | 0.85 (0.68, 1.06) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.09) |

| Adolescent (13–19) | 2100 | 6.7 (6.3, 7.1) | 23.8 (20.8, 27.2) | 0.78 (0.63, 0.97) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.04) | 0.79 (0.63, 0.99) |

| Young Adult (20–44) | 7762 | 6.7 (6.5, 6.9) | 25.7 (24.3, 27.2) | 0.85 (0.74, 0.98) | 0.83 (0.70, 0.98) | 0.84 (0.71, 1.01) |

| Middle Adult (45–64) | 1681 | 7.2 (6.8, 7.6) | 30.0 (27.0, 33.2) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.08) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.10) |

| Older Adult (65+) | 96 | 7.4 (6.0, 8.8) | 37.5 (25.6, 51.1) | 1.38 (0.77, 2.45) | 1.22 (0.64, 2.29) | 1.44 (0.82, 2.52) |

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

P value<0.01,

P value<0.0001 for chi-square test

Model 1 is unadjusted. Model 2 adjusts for Hispanic background, clinical center, age group, and sex. Model 3 adjusts for variables in Model 2, plus education, marital status, number of CVD risk factors, and comorbidity. CVD risk factor counts include smoking status, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Diabetes is defined as fasting glucose greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C greater than or equal to 6.5%, or use of current diabetes medication.

Hypertension is defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or use of current antihypertensive medications.

Dyslipidemia is defined as LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol less than or equal to 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL.

Obesity is defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30.

First generation immigrant refers to foreign born participants with foreign born parents; Second generation immigrant refers to US or foreign born participants with at least one US born parent

Part of the unadjusted two-fold excess odds for depression in the Puerto Rican compared to the Mexican group was accounted for by covariates. However, even after adjustment for demographic, lifestyle, and co-morbid conditions, people of Puerto Rican background were 54% more likely to have high depressive symptoms than those of Mexican origin (OR= 1.54, 95%CI: 1.20–1.98). Individuals aged 45–64 compared to those aged 18–44 had 21% higher likelihood of depression (OR=1.20, 95%CI: 1.07–1.35), and women were twice as likely as men to have high depressive symptoms, even after controlling for multiple covariates. Those born in the US mainland compared to foreign born, or second or higher generation immigrant compared to first, had higher depression scores. After adjustment for multiple variables, odds ratio for depression for US born compared to those born outside of the United States was 1.19 (95%CI: 1.02–1.40). Further adjustments for interview language preference did not change the results, OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.001 – 1.48). Being second or later generation immigrant was also associated with 19% higher likelihood of depression.

Depression and cardiovascular morbidity

History of any CVD (MI, stroke or revascularization/stenting) was associated with 77% higher odds of depression compared to those with no CVD history, after controlling for age, sex, Hispanic/Latino background and clinical center (OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.35, 2.33), Table 2. We did not adjust for CVD risk factors in these analyses since these variables may be in the pathway between depression and CVD morbidity.

Table 2.

Depressive symptoms and cardiovascular disease

| Depression score (CES-D10) | Depression, CES-D10 ≥ 10 | Odds ratios for high depressive symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Prevalence | Model 1* | Model 2* | |||

|

| |||||

| N | Mean (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| History of CVD morbidity‡ | |||||

| None (No MI, revascularization, or stroke) | 15148 | 6.9 (6.7, 7.1) | 26.5 (25.3, 27.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Any CVD | 698 | 8.8 (8.1, 9.5) | 40.9 (35.6, 46.5) | 1.94 (1.54, 2.45) | 1.77 (1.35, 2.33) |

| Type of CVD history | |||||

| Revascularization only | 136 | 9.6 (8.2, 11.0) | 47.1 (36.9, 57.5) | 2.39 (1.56, 3.66) | 1.95 (1.25, 3.04) |

| MI (MI only or MI+revasculartion) | 464 | 9.1 (8.2, 9.9) | 42.4 (35.5, 49.5) | 2.03 (1.53, 2.69) | 1.84 (1.31, 2.59) |

| Stroke only | 182 | 8.0 (6.8, 9.2) | 36.2 (27.9, 45.5) | 1.64 (1.10, 2.45) | 1.53 (1.00, 2.36) |

| MI or stroke (excluding revascularization) | 516 | 9.1 (8.3, 9.9) | 42.8 (36.4, 49.5) | 2.07 (1.58, 2.71) | 1.88 (1.36, 2.59) |

| Number of CVD Risk Factors ‡ | |||||

| 0 | 3503 | 6.0 (5.8, 7.1) | 20.0 (18.1, 22.0) | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 4859 | 7.0 (6.7, 7.3) | 26.7 (24.9, 28.6) | 1.46 (1.27, 1.69) | 1.47 (1.27, 1.70) |

| 2 | 4094 | 7.1 (6.8, 7.4) | 28.5 (26.2, 30.9) | 1.59 (1.35, 1.88) | 1.59 (1.34, 1.89) |

| 3 | 2285 | 7.8 (7.5, 8.2) | 32.6 (30.1, 35.3) | 1.96 (1.67, 2.29) | 1.95 (1.64, 2.31) |

| 4 | 948 | 8.9 (8.2, 9.5) | 41.4 (36.5, 46.4) | 2.80 (2.21, 3.57) | 2.52 (1.97, 3.23) |

| 5 | 106 | 10.6 (9.0, 12.3) | 52.5 (38.7, 65.9) | 4.36 (2.47, 7.70) | 3.38 (1.93, 5.93) |

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

P value <0.0001 for chi-square test

Model 1 is unadjusted. Model 2 adjusts for Hispanic background, clinical center, and age.

CVD risk factor counts include smoking status, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Diabetes is defined as fasting glucose greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C greater than or equal to 6.5%, or use of current diabetes medication.

Hypertension is defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or use of current antihypertensive medications.

Dyslipidemia is defined as LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol less than or equal to 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL.

Obesity is defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30.

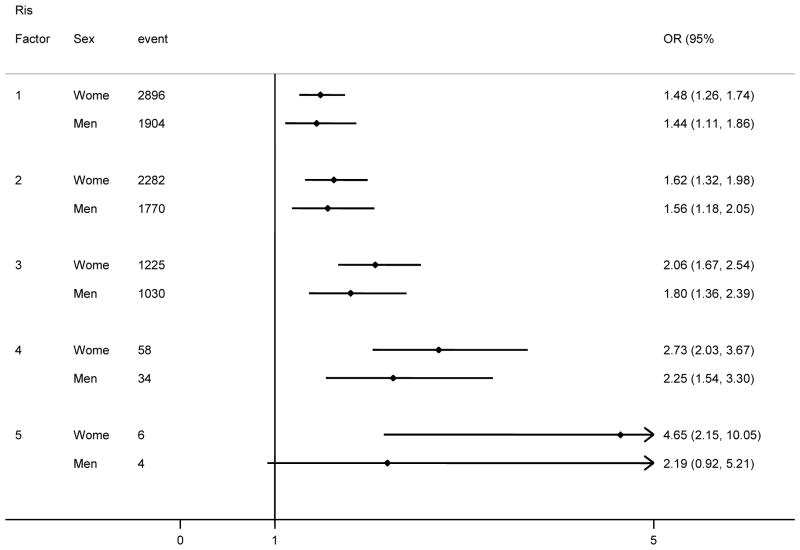

There was an increasingly higher association with depression with each increase in number of CVD risk factors, going from OR= 1.47, (95%CI: 1.27, 1.70) for those with none of the five risk factors to OR= 3.38 (95%CI: 1.93, 5.93) for those with all 5. This effect was more pronounced in women than in men (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Odds ratio of depression by number of CVD risk factors stratified by sex.

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

Models are adjusted for age, sex, Hispanic/Latino background, and clinical center.

Anxiety

Proneness to anxiety followed a similar pattern to depression. The correlation between anxiety and depression scores was 0.71 and thus one would expect a good deal of overlap in high symptom levels on both these scales. The mean anxiety score was 17.0 (95%CI: 16.9, 17.2) and the median was 15.4 (interquartile range: 12.2 – 19.7), Table 3. For comparison purposes, the mean for working adults reported by Mind Garden, Inc., Florida, the publisher of the Adult Manual © 1983 Charles D. Spielberger, states that mean score for working adults was 34.9 on the 20 item scale, which may be interpolated to correspond to 17.5 on the 10-item scale we used.

Table 3.

Mean trait anxiety score by sociodemographic characteristic

| N | Mean (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 15864 | 17.0 (16.9, 17.2) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Hispanic/Latino Background | |||

| Mexican | 6378 | 17.0 (16.7, 17.2) | <.0001 |

| Dominican | 1396 | 17.2 (16.7, 17.7) | |

| Central American | 1684 | 16.5 (16.2, 16.9) | |

| Cuban | 2265 | 16.3 (16.0, 16.6) | |

| Puerto Rican | 2603 | 18.3 (17.9, 18.8) | |

| South American | 1039 | 16.2 (15.8, 16.7) | |

| Sex | <.0001 | ||

| Men | 6356 | 16.2 (16.0, 16.3) | |

| Women | 9508 | 17.8 (17.6, 18.0) | |

| Age Group | <.0001 | ||

| 18–44 | 6488 | 17.0 (16.8, 17.2) | |

| 45–64 | 8103 | 17.3 (17.1, 17.5) | |

| 65–74 | 1273 | 16.2 (15.8, 16.6) | |

| Education | <.0001 | ||

| >HS | 5611 | 16.1 (15.9, 16.3) | |

| HS or equivalent | 4030 | 17.1 (16.8, 17.4) | |

| <HS | 5906 | 18.1 (17.8, 18.3) | |

| Marital Status | <.0001 | ||

| Married/Living with a partner | 8221 | 16.5 (16.3, 16.7) | |

| Single | 4350 | 17.5 (17.3, 17.8) | |

| Divorced | 2605 | 17.5 (17.2, 17.8) | |

| Widowed | 657 | 17.8 (16.6, 18.9) | |

| Acculturation-related Variables | |||

| Nativity | <.01 | ||

| Foreign Born | 13089 | 16.8 (16.6, 17.0) | |

| U.S. Born | 2760 | 17.7 (17.3, 18.0) | |

| Interview language | <.01 | ||

| Spanish | 12707 | 16.8 (16.6, 17.0) | |

| English | 3157 | 17.7 (17.3, 18.0) | |

| Immigrant Generation | <.01 | ||

| First | 12837 | 16.8 (16.6, 17.0) | |

| Second | 2992 | 17.6 (17.3, 18.0) | |

| Age at immigration | <.01 | ||

| U.S. Born | 2760 | 17.7 (17.3, 18.0) | |

| Child (0–12) | 1409 | 17.4 (16.9, 17.9) | |

| Adolescent (13–19) | 2100 | 17.1 (16.7, 17.5) | |

| Young Adult (20–44) | 7762 | 16.6 (16.4, 16.8) | |

| Middle Adult (45–64) | 1681 | 16.6 (16.2, 17.0) | |

| Older Adult (65+) | 96 | 16.9 (15.5, 18.3) | |

| Cardiovascular Disease-related Variables | |||

| History of CVD morbidity | <.01 | ||

| None (No MI, revascularization, or stroke) | 15148 | 17.0 (16.8, 17.1) | |

| Any CVD | 698 | 18.1 (17.5, 18.7) | |

| Number of risk factors | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 3503 | 16.4 (16.2, 16.7) | |

| 1 | 4859 | 17.0 (16.7, 17.3) | |

| 2 | 4094 | 17.2 (16.9, 17.5) | |

| 3 | 2285 | 17.4 (17.1, 17.7) | |

| 4 | 948 | 18.0 (17.4, 18.6) | |

| 5 | 106 | 19.3 (17.5, 21.1) | |

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

P value obtained from T-test or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

CVD = coronary heart disease, or stroke

CHD = coronary heart disease, includes self-report of myocardial infarction, balloon angioplasty, a stent, or bypass surgery in coronary arteries.

CVD risk factor counts include smoking status, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Diabetes is defined as fasting glucose greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C greater than or equal to 6.5%, or use of current diabetes medication.

Hypertension is defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or use of current antihypertensive medications.

Dyslipidemia is defined as LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol less than or equal to 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL.

Obesity is defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30.

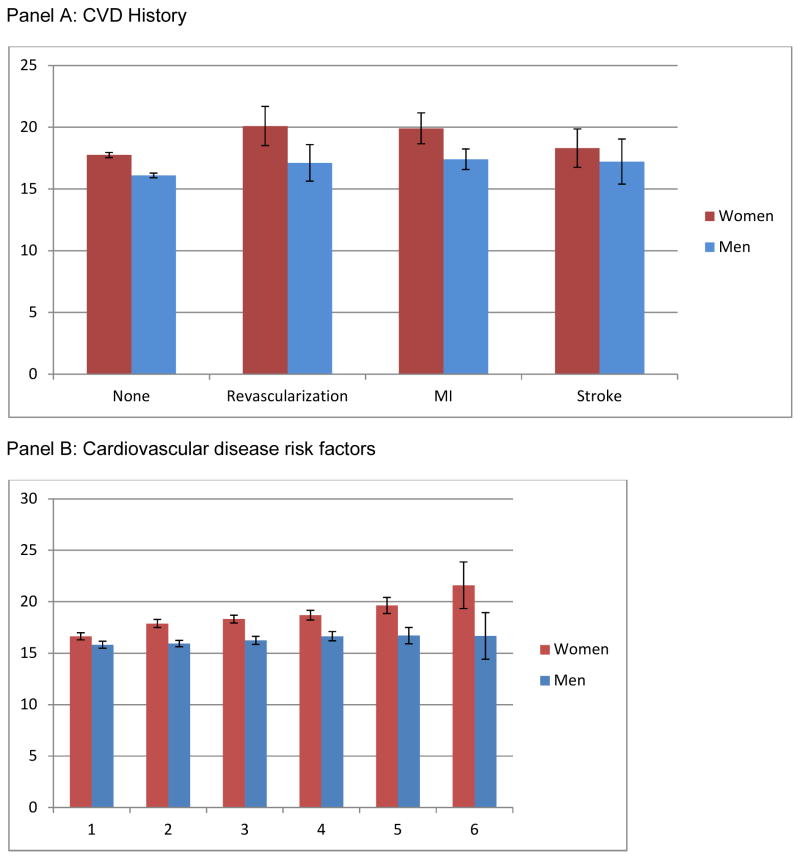

There were significantly higher anxiety scores for those of Puerto Rican background, the middle-aged, less educated, not married or living with a partner, born in the US mainland or who came to the US at earlier ages as children or adolescents and those who had any history of CVD. Anxiety scores were higher for women than for men at each level of number of risk factors for CVD (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Age-adjusted mean Anxiety score by CVD history stratified by sex.

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

None if no MI, revascularization, or stroke.

Revascularization refers to persons with revascularization only, excludes person with MI or stroke.

MI refers to persons with MI or revascularization, excludes persons with stroke.

Stroke refers to persons with stroke only, excludes persons with MI or revascularization.

CVD risk factor counts include smoking status, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Diabetes is defined as fasting glucose greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C greater than or equal to 6.5%, or use of current diabetes medication.

Hypertension is defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or use of current antihypertensive medications.

Dyslipidemia is defined as LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol less than or equal to 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL.

Obesity is defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30

Antidepressant and antianxiety medications usage

Overall, 5.0% of the cohort used antidepressant medications (Table 4). There were marked differences in use by insurance status, with 8.2% of insured versus 1.8% of uninsured using antidepressants. Among antidepressant users, 62.7% solely used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), 10.4% solely used tricyclic antidepressants and 26.8% used combinations or other antidepressants (data not shown). Those of Cuban or Puerto Rican background had the highest proportion of use. Antidepressant use increased with age, with 2.4% of those ages 18–44 compared to 12.6% of those 65 or older using antidepressants; 15.4% of those with history of CHD or stroke were taking antidepressants. Anti-anxiety medications were used by 2.5% of the cohort (not mutually exclusive), and though the use was lower, it follows the same pattern as antidepressant use. The highest use of antidepressants was by those with history of CVD morbidity; 20.3% of those with a history of stroke, 19.5% of those with a history of revascularization and 14.4% of those with a history of MI used antidepressants. A similar pattern was apparent for use of anti-anxiety agents. Antidepressant and antianxiety medication use also went up with increasing number of risk factors both among those who scored below and above the cut-point for depression.

Table 4.

Anti-depression and anti-anxiety medication use

| Overall | By Depression Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Anti-depressive medication use | Anti-anxiety medication use | Among low depressive CESD <10 | Among high depressive CESD ≥10 | ||||

| Subgroup N | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | Subgroup N | % (95% CI) | Subgroup N | % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 15586 | 5.0 (4.5, 5.5) | 2.5 (2.1, 3.0) | 10983 | 2.9 (2.5, 3.4) | 4603 | 10.5 (9.4, 11.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino | |||||||

| Background | |||||||

| Dominican | 1378 | 5.5 (4.1, 7.3) | 2.2 (0.7, 7.2) | 983 | 2.5 (1.4, 4.5) | 395 | 13.4 (9.6, 18.5) |

| Central American | 1660 | 2.5 (1.7, 3.6) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) | 1187 | 2.0 (1.2, 3.1) | 473 | 4.1 (2.3, 7.1) |

| Cuban | 2243 | 7.2 (5.9, 8.7) | 6.0 (4.7, 7.5) | 1536 | 4.5 (3.3, 6.1) | 707 | 14.0 (11.1, 17.5) |

| Mexican | 6240 | 3.3 (2.7, 3.9) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.5) | 4703 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) | 1537 | 7.5 (5.8, 9.5) |

| Puerto Rican | 2575 | 8.3 (7.0, 9.8) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.7) | 1502 | 4.5 (3.3, 6.1) | 1073 | 14.4 (12.0, 17.2) |

| South American | 1016 | 2.3 (1.4, 3.6) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.5) | 752 | 1.1 (0.5, 2.7) | 264 | 6.0 (3.6, 9.8) |

| Mixed/Other | 474 | 3.8 (1.6, 8.4) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.5) | 320 | 3.6 (1.0, 12.2) | 154 | 4.4 (2.2, 8.7) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 6266 | 3.3 (2.7, 4.0) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.0) | 4806 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.6) | 1363 | 8.5 (6.8, 10.7) |

| Female | 9320 | 6.5 (5.9, 7.3) | 3.4 (2.8, 4.2) | 5816 | 4.0 (3.3, 4.8) | 3240 | 11.7 (10.3, 13.3) |

| Age Group | |||||||

| 18–44 | 6390 | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 4806 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) | 1584 | 5.2 (4.1, 6.6) |

| 45–64 | 7958 | 7.8 (7.0, 8.7) | 3.9 (3.3, 4.6) | 5336 | 4.1 (3.5, 4.8) | 2622 | 15.6 (13.8, 17.6) |

| 65+ | 1238 | 12.6 (9.8, 16.1) | 7.0 (5.2, 9.3) | 841 | 9.2 (6.3, 13.3) | 397 | 20.4 (14.7, 27.4) |

| Education | |||||||

| <HS | 5931 | 5.8 (5.0, 6.8) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.3) | 3886 | 3.1 (2.5, 4.0) | 2045 | 11.3 (9.5, 13.4) |

| HS or equivalent | 4036 | 4.0 (3.3, 4.8) | 2.5 (1.6, 3.8) | 2900 | 2.2 (1.7, 3.0) | 1136 | 8.7 (7.0, 10.8) |

| >HS | 5619 | 5.0 (4.2, 6.0) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.2) | 4197 | 3.2 (2.4, 4.3) | 1422 | 11.2 (9.2, 13.5) |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Single | 4284 | 4.5 (3.7, 5.3) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.7) | 2928 | 2.5 (1.9, 3.4) | 1356 | 9.3 (7.6, 11.4) |

| Married/Living with a partner | 8093 | 3.8 (3.2, 4.5) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.1) | 6075 | 2.3 (1.8, 3.1) | 2018 | 8.6 (7.1, 10.3) |

| Divorced | 2573 | 9.4 (7.9, 11.3) | 3.7 (2.8, 5.0) | 1582 | 5.5 (4.1, 7.5) | 991 | 16.3 (13.6, 19.5) |

| Widowed | 636 | 10.7 (8.1, 14.0) | 6.1 (4.0, 9.1) | 398 | 7.7 (5.1, 11.5) | 238 | 16.0 (10.4, 23.8) |

| Insurance Status | |||||||

| Insured | 7856 | 8.2 (7.3, 9.2) | 3.2 (2.7, 3.9) | 5373 | 4.9 (4.1, 5.9) | 2483 | 16.3 (14.3, 18.4) |

| Not insured | 7690 | 1.8 (1.5, 2.2) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 5590 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | 2100 | 4.1 (3.2, 5.1) |

|

| |||||||

| History of CVD morbidity | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| None | 15148 | 4.6 (4.1, 5.1) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.9) | 10797 | 2.8 (2.3, 3.3) | 4351 | 9.6 (8.6, 10.9) |

| Revascularization | 136 | 19.5 (11.7, 30.5) | 12.0 (6.3, 21.6) | 76 | 15.0 (7.8, 26.9) | 60 | 24.5 (12.9, 41.4) |

| MI | 464 | 14.4 (10.8, 18.8) | 8.7 (5.9, 12.7) | 269 | 8.6 (5.6, 12.9) | 196 | 22.2 (15.5, 30.8) |

| Stroke | 182 | 20.3 (13.6, 29.2) | 5.0 (1.6, 14.7) | 109 | 15.5 (8.0, 27.7) | 73 | 28.9 (17.7, 43.3) |

| MI or stroke | 516 | 13.5 (10.3, 17.6) | 8.8 (6.1, 12.5) | 296 | 8.3 (5.6, 12.3) | 220 | 20.4 (14.4, 28.1) |

|

| |||||||

| ANY CVD | 698 | 15.4 (12.3, 19.2) | 7.7 (5.4, 11.0) | 405 | 10.5 (7.3, 14.9) | 293 | 22.5 (16.9, 29.3) |

|

| |||||||

| Number of CVD risk factors | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 0 | 3503 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.4) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | 2725 | 1.4 (1.0, 2.1) | 778 | 3.6 (2.5, 5.3) |

| 1 | 4859 | 3.9 (3.2, 4.7) | 2.3 (1.8, 2.9) | 3475 | 2.6 (1.9, 3.6) | 1384 | 7.4 (6.0, 9.2) |

| 2 | 4094 | 5.8 (4.9, 7.0) | 3.0 (2.1, 4.4) | 2861 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.5) | 1233 | 11.7 (9.2, 14.8) |

| 3 | 2285 | 8.3 (6.9, 10.0) | 3.8 (2.9, 5.1) | 1492 | 4.5 (3.3, 6.1) | 793 | 16.3 (13.3, 19.8) |

| 4 | 948 | 1.9 (10.9, 17.5) | 4.9 (3.5, 7.0) | 564 | 8.4 (5.4, 12.9) | 384 | 21.7 (16.1 (28.6) |

| 5 | 106 | 25.3 (15.7, 38.3) | 10.5 (4.6, 22.4) | 51 | 22.1 (8.8, 45.3) | 55 | 28.3 (16.0, 45.0) |

All estimates, except n, account for probability sampling.

CVD risk factor counts include smoking status, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

Diabetes is defined as fasting glucose greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL, or non-fasting glucose greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1C greater than or equal to 6.5%, or use of current diabetes medication.

Hypertension is defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure is greater than or equal to 140/90 mmHg or use of current antihypertensive medications.

Dyslipidemia is defined as LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 160 mg/dL, or HDL cholesterol less than or equal to 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides greater than or equal to 200 mg/dL.

Obesity is defined as BMI greater than or equal to 30.

DISCUSSION

In the most comprehensive study of Hispanics/Latinos of different national backgrounds conducted to date (the HCHS/SOL), we found an overall prevalence of depression of 27%. Being U.S. born or 2nd or higher generation immigrant was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication was used by 5% and 2.5% of the cohort respectively and varied widely by Hispanic/Latino background group as well by age and sex and presence of cardiovascular disease.

Those of Puerto Rican background experienced the highest levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety proneness, even after adjusting for multiple demographic, lifestyle and risk factor covariates. Among those of Puerto Rican background 38% reported high depressive symptoms, compared to 22% of those with Mexican background. In NHANES, Puerto Ricans in New York City as well as those on the island of Puerto Rico had 28.1% and 28.6% prevalence, respectively, of high depressive symptomatology as measured on a longer version of the same screening instrument used here, (CES-D)13. In our study, even after adjustment for multiple covariates, those of Puerto Rican background were 58% more likely to have high depressive symptoms than those of Mexican background. While, analysis of the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) of 2,554 subjects combined with the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) of 4,222 subjects, found that Hispanic/Latinos had lower rates of depressive disorders (15.4%) than Non-Latino Whites (22.3%), and lower rates of anxiety disorders (15.7% versus 25.7%), persons of Puerto Rican and Cuban background had higher rates than those of Mexican background15.

Another study of a national probability sample 16 also found varying rates among different national background groups of major depression in the past 12 months as well as lifetime depression, ascertained by clinical interview, with rates being highest in Puerto Ricans. Being born in the U.S. compared to foreign born, second-generation immigrants or later and living longer in the U.S. were all associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety. Other studies showed similar results 7, 16. Cook and colleagues17 link certain psychosocial and cultural conflicts as mediators of the relationship between mental health and exposure to the U.S. culture, but this topic requires more study.

We found that history of CVD was associated with 77% higher likelihood of depression, independently of age, sex or Hispanic background. We cannot determine whether depression and anxiety followed or preceded the cardiovascular event. However, the depression scale asks about symptoms and feelings in the past week while the MI, revascularization or stroke occurred prior to the time of the visit at which the questionnaires were administered. The anxiety scale asks about anxiety proneness in general, not within a specific time frame. Both anxiety and depression are risk factors for cardiovascular events3, 4, 18–21 and depression is associated with a poorer prognosis after an MI 22. A meta-analysis of anxiety found a 26% increase in risk of incident CHD and 48% increase in risk of cardiac deaths4. The Heart and Soul Study of over 1,000 patients with stable coronary heart disease, found 74% increased risk of cardiovascular events among those with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) compared to those not anxious, independent of multiple variables including severity of their coronary heart disease 18. Another meta-analysis 21 found that depression was associated with 46% increased risk of CVD and 55% increased risk of cardiac death. These increased risks are similar, and sometimes higher, in magnitude to traditionally recognized other risk factors like hypertension, and high cholesterol. Most recently, Lichtman and colleagues published a “Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association” which reviewed 53 individual studies and 4 meta-analyses on the role of depression among patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and recommends that the American Heart Association elevate depression to the status of a risk factor in those with ACS22.

Anti-depressant use in our overall cohort (5.0%) and, in some of the Hispanic/Latino national background groups, was lower than that reported for non-Hispanic whites23. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) of 2005–2008 show that 13.6% of Non-Hispanic whites were taking antidepressant medication. The CESP study found that Mexican Americans with major depressive disorder were less likely to be treated with either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy than Cubans or Puerto Ricans16, 24. Our findings suggest possible under treatment in certain national background groups (2.5%, 2.3% 3.3% in Central Americans, South Americans and Mexicans, respectively). A large part of the under treatment is likely due to lack of health insurance; antidepressant use was 4 times higher among the insured (8.2%) compared to those without health insurance (1.8%). Participants with a history of CVD were more likely to be using anti-depressant (13.3%) and anti-anxiety (8.8%) medication than those without such a history of whom 4.6% and 2.5% used antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs respectively). Whether these medications prevent recurring CVD events or death is not clear but there is good evidence that post-MI depression carries a poorer prognosis for all-cause and cardiac mortality 22. Participants with more CVD risk factors, also used medications more frequently, in keeping with their higher rates of depression.

Our finding that those of Puerto Rican background have the highest levels of depression and anxiety should be viewed in light of some limitations of our study. Puerto Ricans have higher burden of chronic diseases than other groups in our study25 that may put them at higher risk of depression and anxiety. Although we controlled for these and other factors in our multivariable analyses, residual confounding may remain. We did not examine the presence and/or, modifying effects of social support, and other psychosocial factors.

We found that high depressive symptoms and high anxiety, were more prevalent in those who were U.S. born, second or later generation immigrants and lived in the U.S. the longest. Other studies have found similar relationships. In a study of 281 first generation, adolescents, Perreira and colleagues26–28 found, in a primarily Mexican sample, that stressors pre and post-migration contribute to depression but social support reduces the likelihood of depression. Reasons for high depressive symptoms and anxiety proneness in those born in the U.S. and in those being more acculturated to American culture needs to be investigated.

The findings presented here are from the largest, most comprehensive study to date of the mental health of Hispanics/Latinos of different national backgrounds. The results show that certain background groups have considerably higher rates of depression and anxiety than those of Mexican background, which is the group most studied. Prevalence of depression and anxiety varies with age, sex, time residing in the U.S., and presence of cardiovascular risk factors or history of cardiovascular events. The relatively lower rate of use of anti-depressant medications may represent under treatment, particularly among those with no insurance. Although genetic and environmental factors could be linked to depression and anxiety, chronic health issues and socioeconomic stressors can also precipitate or accentuate them. Increasing awareness, and reducing the burden that undiagnosed or untreated depression and anxiety cause to health of Hispanics/Latinos and the U.S. population at large must be part of the national public health agenda.

Highlights.

We present mental health data from the largest study of diverse Hispanic groups.

Depression and anxiety vary by Hispanic group, being highest among Puerto Ricans.

Longer exposure to U.S. culture is associated with higher depression and anxiety.

CVD risk factors and morbidity are associated with higher depression and anxiety.

There may be undertreatment of depression, especially among uninsured.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions.

Investigators website - http://www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/

FUNDING

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NIH Institution-Office of Dietary Supplements.

Abbreviations

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- GAD

generalized anxiety disorder

- MI

myocardial infarction

- HCHS/SOL

Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos

- NLAAS

National Latino and Asian American Study

- CPES

Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys

- CES-D10

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale- 10 items

- STAS

Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale

- PTCA

percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

- OR

odds ratio

- 95%CI

95% confidence interval

- NCS-R

National Comorbidity Survey Replication

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys

- SSRI

selective serotonin receptor inhibitors

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors report no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, Talavera GA, Greenland P, Cochrane B, Robbins J, Aragaki A, Dunbar-Jacob J. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. The women’s health initiative (whi) Archives of internal medicine. 2004;164:289–298. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Applegate WB, Berge K, Chang CJ, Davis BR, Grimm R, Jr, Kostis J, Pressel S, Schron E. Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events. Shep cooperative research group (systoloc hypertension in the elderly) Archives of internal medicine. 1996;156:553–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salaycik KJ, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser A, Nguyen AH, Brady SM, Kase CS, Wolf PA. Depressive symptoms and risk of stroke: The framingham study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38:16–21. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251695.39877.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roest AM, Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Denollet J. Anxiety and risk of incident coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thombs BD, Bass EB, Ford DE, Stewart KJ, Tsilidis KK, Patel U, Fauerbach JA, Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006;21:30–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poynter B, Shuman M, Diaz-Granados N, Kapral M, Grace SL, Stewart DE. Sex differences in the prevalence of post-stroke depression: A systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:563–569. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across latino subgroups in the united states. American journal of public health. 2007;97:68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, Liu K, Giachello A, Lee DJ, Ryan J, Criqui MH, Elder JP. Sample design and cohort selection in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Annals of epidemiology. 2010;20:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, Raij L, Talavera G, Allison M, Lavange L, Chambless LE, Heiss G. Design and implementation of the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Annals of epidemiology. 2010;20:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the ces-d (center for epidemiologic studies depression scale) American journal of preventive medicine. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radloff LS. The ces-d scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia M, Marks G. Depressive symptomatology among mexican-american adults: An examination with the ces-d scale. Psychiatry research. 1989;27:137–148. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vera M, Alegria M, Freeman D, Robles RR, Rios R, Rios CF. Depressive symptoms among puerto ricans: Island poor compared with residents of the new york city area. American journal of epidemiology. 1991;134:502–510. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Mirzaei F, O’Reilly EJ, Winkelman J, Malhotra A, Okereke OI, Ascherio A, Gao X. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and risk of depression in women. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;176:279–288. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout P, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, Torres M, Chen C-n, Meng X-L. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, Vega WA. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the united states. Journal of psychiatric research. 2010;44:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook B, Alegria M, Lin JY, Guo J. Pathways and correlates connecting latinos’ mental health with exposure to the united states. American journal of public health. 2009;99:2247–2254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martens EJ, de Jonge P, Na B, Cohen BE, Lett H, Whooley MA. Scared to death? Generalized anxiety disorder and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease:The heart and soul study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010;67:750–758. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutledge T, Linke SE, Johnson BD, Bittner V, Krantz DS, Cornell CE, Vaccarino V, Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Eteiba W, Shaw LJ, Parashar S, Eastwood JA, Vido DA, Merz CN. Relationships between cardiovascular disease risk factors and depressive symptoms as predictors of cardiovascular disease events in women. Journal of women’s health. 2012;21:133–139. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutledge T, Linke SE, Krantz DS, Johnson BD, Bittner V, Eastwood JA, Eteiba W, Pepine CJ, Vaccarino V, Francis J, Vido DA, Merz CN. Comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms as predictors of cardiovascular events: Results from the nhlbi-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise) study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2009;71:958–964. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bd6062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and meta analysis. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2007;22:613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtman JH, Froelicher ES, Blumenthal JA, Carney RM, Doering LV, Frasure-Smith N, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS, Leifheit-Limson EC, Sheps DS, Vaccarino V, Wulsin L, Stroke N American Heart Association Statistics Committee of the Council on E, Prevention, the Council on C. Depression as a risk factor for poor prognosis among patients with acute coronary syndrome: Systematic review and recommendations: A scientific statement from the American Heart Asociation. Circulation. 2014;129:1350–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pratt LA, Brody DJ, Gu Q. Antidepressant use in persons aged 12 and over: United states, 2005–2008. NCHS data brief. 2011:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the united states: Too little for too few. Archives of general psychiatry. 2010;67:37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Sorlie PD, Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among hispanic/latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the united states. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potochnick SR, Perreira KM. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant latino youth: Key correlates and implications for future research. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2010;198:470–477. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4ce24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ornelas IJ, Perreira KM. The role of migration in the development of depressive symptoms among latino immigrant parents in the USA. Social science & medicine. 2011;73:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perreira KM, Ornelas IJ. The physical and psychological well-being of immigrant children. The Future of children/Center for the Future of Children, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. 2011;21:195–218. doi: 10.1353/foc.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]