Abstract

Objective

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening is controversial. A community jury allows presentation of complex information and may clarify how participants view screening after being well-informed. We examined whether participating in a community jury had an effect on men's knowledge about and their intention to participate in PSA screening.

Design

Random allocation to either a 2-day community jury or a control group, with preassessment, postassessment and 3-month follow-up assessment.

Setting

Participants from the Gold Coast (Australia) recruited via radio, newspaper and community meetings.

Participants

Twenty-six men aged 50–70 years with no previous diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Intervention

The control group (n=14) received factsheets on PSA screening. Community jury participants (n=12) received the same factsheets and further information about screening for prostate cancer. In addition, three experts presented information on PSA screening: a neutral scientific advisor provided background information, one expert emphasised the potential benefits of screening and another expert emphasised the potential harms. Participants discussed information, asked questions to the experts and deliberated on personal and policy decisions.

Main outcome and measures

Our primary outcome was change in individual intention to have a PSA screening test. We also assessed knowledge about screening for prostate cancer.

Results

Analyses were conducted using intention-to-treat. Immediately after the jury, the community jury group had less intention-to-screen for prostate cancer than men in the control group (effect size=−0.6 SD, p=0.05). This was sustained at 3-month follow-up. Community jury men also correctly identified PSA test accuracy and considered themselves more informed (effect size=1.2 SD, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Evidence-informed deliberation of the harms and benefits of PSA screening effects men's individual choice to be screened for prostate cancer. Community juries may be a valid method for eliciting target group input to policy decisions.

Trial registration number

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12612001079831).

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, PUBLIC HEALTH, Prostate Specific Antigen testing, Prostate Cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to use scientific methods to evaluate the effect of a community jury on an individual's knowledge and decisions.

Participants in community juries make value-based decisions from complex information and can differentiate individual from community choices.

Expert presentations were based on large population studies that have limitations.

The sample size of this study was small, but the results were clear and sustained.

How sampling, recruitment techniques and group processes affect community jury outcomes are yet to be examined.

Introduction

Screening for prostate cancer by prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is controversial1 and the benefits and harms of screening are uncertain.2 The results of two large randomised controlled trials of population screening (the ERSPC trial in Europe3 and the PLCO trial in the USA4) were much anticipated, but the differing methods and results have led to conflicting interpretations and recommendations from expert groups.5 6 Given the uncertainty, most guidelines recommend that men should be fully informed of the potential advantages and disadvantages of screening prior to having a PSA test.5 7 8 Although individuals vary in the degree to which they want to engage themselves with the evidence about their health concerns, a majority consistently report an interest in sharing healthcare decisions with their treating doctor.9 10 However, providing the complex information relevant to men who are interested in PSA screening remains challenging.

Citizens’ deliberation methodologies such as community juries can facilitate the communication of complex evidence and aim to elicit ‘informed’ community perspectives for the purpose of guiding services and public policy. A range of community jury processes have been described, but the common features are (1) participants are drawn from the lay public; (2) the jury deliberates on a question requiring an ethical or value-based decision (as opposed to a problem requiring a technical solution); (3) the jury is provided with information on the relevant issues and possible positions from expert ‘witnesses’, with the opportunity to ask them questions and (4) the jury then engages in a deliberation phase with participants discussing their preferences, opinions, values and positions, and attempt to reach a consensus position.11

Community juries have been conducted on topics such as public health priorities,12 mammography screening13 and health research.14 15 A recent review of deliberation methodologies found only four unique studies that compared deliberative methodologies with a control group; only two of these were in relation to health topics.11 While theoretically sound,11 community juries are a resource-intensive process and it is uncertain whether the views of those participating are better ‘informed’ than those of a public provided with reading material on the same topic. It is also unclear whether and how being informed influences a jury's conclusions. If community juries are to be used to inform screening policy, it is essential to understand the capacity of a community jury process to support better-informed conclusions by its participants.

The aim of this study was to examine the degree to which participants of a community jury on PSA screening of asymptomatic men were better ‘informed’ than other citizens and, based on the ERSPC3 and PLCO4 trials together with the general practice guidelines, whether evidence-informed deliberations of the benefits and harms of PSA screening impact on men's intention to be screened for prostate cancer. We conducted a randomised controlled trial that compared a community jury with men allocated to receive typical information. As part of the community jury process, men were also asked to deliberate on two community-focused questions:

Should government campaigns be provided (on PSA screening) and if so, what information should be included in those campaigns?

What do you, as a group of men, think about a government organised invitation programme for testing for prostate cancer?

This is the first randomised controlled trial of a deliberative democracy process on the topic of PSA screening.

Method

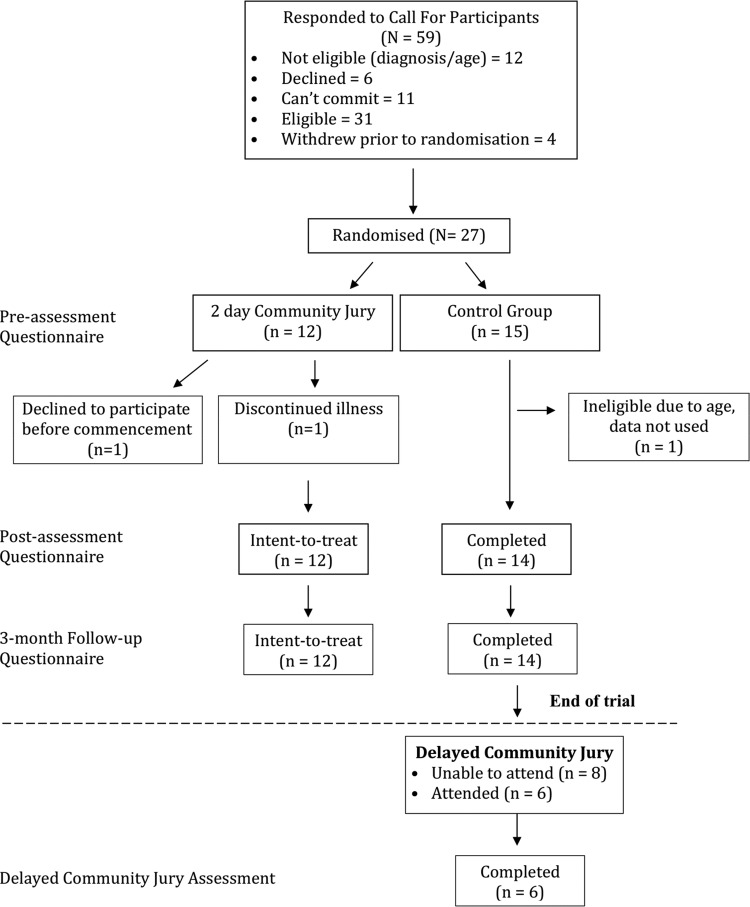

We recruited men in the target age group of 50–70 years from the Gold Coast region (Australia) who had no previous diagnosis of prostate cancer, using media advertisements, radio interviews and community groups. Men with a family history of prostate cancer were not excluded from participating. Eligible and available respondents attended a session on a Friday evening to receive a full briefing on the study; all agreed to participate and completed a consent form, before being randomly allocated to either a community jury group or a control group (figure 1). Random allocation occurred by each man selecting a piece of paper with the name of either group from an opaque container. The protocol is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12612001079831).

Figure 1.

Consort flow-chart of participants.

All men were given standard PSA fact sheets from the Cancer Council Australia and Andrology Australia.16 17 In addition to the factsheets, men in the community jury group also received a Cochrane Collaboration plain language statement,2 information from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ Guidelines for “Preventive Activities in General Practice” pertaining to screening for prostate cancer,7 and the Executive Summary of ‘PSA Testing’ from the Urology Society of Australia and New Zealand.8 Men in both groups received $20 gift cards as reimbursement for their time at the introductory session and for each survey. The community jury group received an $80 gift card as reimbursement for attending the community jury weekend. Men in the control group were given a follow-up survey with a return-stamped envelope to be mailed after the weekend.

The community jury weekend and a qualitative analysis of the jury deliberations have been described in detail elsewhere.18 In brief, the community jury consisted of an iterative process of education and deliberation. Three experts presented to the community jury on day one: a neutral scientific advisor discussed medical information regarding the role of the prostate, screening tests (including PSA and digital rectal examination), explanations about changes to PSA levels, how cancer is detected, and treatment options and potential outcomes (Jim Dickinson, Professor of Family Medicine, University of Calgary). Two further experts, a urologist and expert in prostate cancer (RG) and an expert in evidence-based medicine (PG) presented the benefits and harms of being screened for prostate cancer. Although both speakers aimed to give balanced presentations, one emphasised the benefits of PSA screening, in particular selective screening (RG http://youtu.be/9vPt3NAcG8g) and the other the harms (PG http://youtu.be/nifkjdZKmsU). Both presentations focused on the evidence from the two trials of PSA population screening. However, both presenters also made reference to lower levels of evidence relating to the risks of metastases if a cancer remains undetected due to a lack of screening and the consequences of treating a localised disease detected during screening. After each presentation, the men were able to deliberate on the information and could ask the experts any questions. The men reflected on the information overnight and then returned on Sunday to deliberate and discuss the information presented the day before, including asking any further questions to the expert witnesses by phone.

A nominal group technique was used on both days to elicit individual thoughts prior to group deliberations. After the final deliberations on Sunday, including the community-level decisions, the men in the community jury completed the postassessment survey. Men in the control group were contacted on Monday and either completed the postassessment survey by phone or mailed the survey back to researchers the same week. Three months after the community jury weekend, all men in both groups were recontacted and completed a follow-up survey.

Non-protocol extension

Since they indicated a strong desire to have the experience of the community jury weekend, after their 3-month follow-up survey the control group was offered the same community jury experience. Six of the 14 men randomised to the control group participated in the second community jury (figure 1). The two primary experts were the same as for the original community jury group; however, the scientific advisor was changed to a female general practitioner and professor of clinical epidemiology (JD). A final postjury survey was conducted with the second community jury.

Measures

We collected demographic information, history of previous PSA testing and information sources for PSA screening at the introductory session. In each of the three surveys, the men were asked to nominate on a scale 0–10 (0=not at all, 5=maybe and 10=absolutely), whether they intended, while symptomless, to undergo PSA screening for prostate cancer in the future. They were also asked to nominate how informed they considered themselves to be in relation to the harms and benefits of screening for prostate cancer on a scale 0–4 (0 = not at all and 4=very). We asked four knowledge questions in each survey that assessed (A) the men's knowledge about the recommendation on PSA screening in the Australian general practice guidelines,7 (B) the accuracy of the PSA test and (C) two questions about the treatment options and side effects of prostate cancer treatment (box 1). Australia has a primary care-based system, requiring a referral from a general practitioner to see a urologist. General practitioners are therefore responsible for the majority of the PSA screening tests requested in Australia. For this reason, we were interested in the participants’ knowledge of current general practice guidelines.

Box 1. Knowledge questions from surveys* (answers considered correct highlighted).

-

Is routine testing for prostate cancer recommended by Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ (RACGP) Guidelines?

□ Yes □ No □ Do not know

-

How accurate do you think the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test is for diagnosing prostate cancer?

□Reasonably accurate but some people who do have cancer can have a negative test result (false negative)

□Reasonably accurate but some people who do not have cancer can have an abnormal result (false positive)

□The PSA test is not always accurate because it can have both false-positive or false-negative results

□The PSA test is completely accurate

□Do not know

-

In terms of your knowledge about prostate cancer, could you list some treatment options?

□ No □ Yes, please list

-

Could you list some potential side effects of treatments for prostate cancer?

□ No □ Yes, please list

*There were originally six knowledge questions however the answers for two (one on prevalence and the other on mortality rates of prostate cancer) were incorrect and were deleted from analyses.

Statistical analyses

Preassessment to postassessment and postassessment to follow-up assessment differences between the groups were examined with analysis of covariance and Fisher's exact test. It was anticipated that the number of PSA tests previously undertaken would impact on a man's future decision to be screened for prostate cancer with the PSA test.19 Therefore, we conducted the analyses with adjustment for baseline intention-to-screen and the number of times a man had already received a PSA test. Unadjusted postassessment analyses were conducted using an independent t test. All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis.

Results

Participant demographics

Of the 59 men who contacted the research team, 27 respondents were available on the set date and elected to participate in the study. One man was excluded postrandomisation as his age exceeded the limit of the study (see figure 1). The participating men's ages ranged between 53 and 70 years (average 62 years, SD=4.8). Further demographic information is described in table 1. There was no loss to follow-up during the course of the study. The groups were similar at baseline in age, number of times previously screened for prostate cancer, and whether they intended to be screened for prostate cancer in the future. All but 3 men had previously had a PSA test; 14 had been tested two or three times, 4 on one occasion, 2 men six times and 3 men had been tested on 7, 8 and 12 occasions each. No men had undergone a biopsy. At preassessment, the majority of men (16/26, 62%) agreed with the statement that routine screening for prostate cancer saved lives, whereas 4 (15%) disagreed and 6 (23%) did not know (table 1). The men reported a variety of sources for how they had accessed information about prostate cancer screening, with the most common source of information being their general practitioner (table 2).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Community jury (n=12) | SD/% | Control (n=14) | SD/% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 61 | (4.8) | 62 | (4.9) |

| Number previous PSA tests | ||||

| Mean | 3.9 | (3.6) | 2.2* | (1.8) |

| Routine PSA testing saves lives | ||||

| Frequency | ||||

| Yes | 7 | (58%) | 9 | (64%) |

| No | 2 | (17%) | 2 | (14%) |

| Do not know | 3 | (25%) | 3 | (21%) |

| Education | ||||

| Frequency | ||||

| High school or less | 2 | (17%) | 4 | (28%) |

| Some university or TAFE | 4 | (33%) | 4 | (28%) |

| University/TAFE graduate | 4 | (33%) | 1 | (7%) |

| University postgraduate | 2 | (17%) | 5 | (36%) |

*n=13 (1 missing).

PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TAFE, Technical and Further Education Institutions.

Table 2.

Where do men receive information about testing for prostate cancer

| Agree | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| I do not look for information | 3 | (12) |

| Family and friends | 11 | (42) |

| Internet | 10 | (38) |

| Media | 9 | (35) |

| General practitioner | 17 | (65) |

| Urologist/specialist/hospital | 5 | (20) |

N=26.

Men could endorse more than one source.

Changes in intention-to-screen and individual knowledge

Preintervention to postintervention

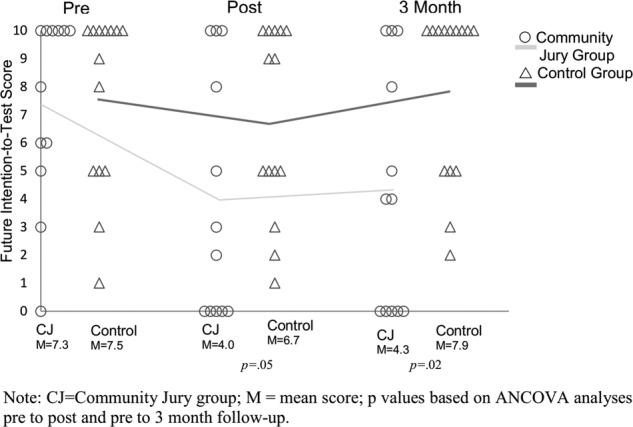

At postassessment, men in the community jury group had significantly less intention-to-screen for prostate cancer on the 0–10 scale than men in the control group (median score 2.5 and 7, effect size=−0.6 SD, p=0.05). When we adjusted for baseline intention to be screened for prostate cancer and the number of prior PSA tests, the mean difference was 3.7 (p=0.005, table 3). The unadjusted mean difference between the groups was 2.7 (figure 2).

Table 3.

Linear regression analysis predicting future intention-to-screen for prostate cancer

| Coefficient | SE β | CI lower | CI upper | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.16 | 1.69 | −3.66 | 3.35 | 0.93 |

| Preassessment intention-to-screen score | 0.74 | 0.18 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.001 |

| Number of previous PSA tests | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 1.07 | 0.008 |

| Group (community jury/control) | −3.69 | 1.19 | −6.16 | −1.21 | 0.005 |

N=25.

These data are slightly different to Rychetnik et al's18 analyses as they are based on intention-to-treat.

PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Figure 2.

Future intention-to-screen scores at preassessment, postassessment, and 3-month follow-up assessment. ○ Community jury group; Δ control group. CJ, community jury group; M, mean score; p values based on analysis of covariance preassessment to postassessment and preassessment to 3-month follow-up assessment.

After completion of the community jury weekend, men in the jury group considered themselves more informed about screening for prostate cancer than the control group (median score 4 and 2, mean difference=1.7, effect size=1.2 SD, p<0.001). Compared with the control group, the community jury group was more likely to correctly identify that the PSA test was not always accurate in indicating the likelihood of prostate cancer as it had both false-positive and false-negative results (p=0.03, table 4).

Table 4.

Changes in men's knowledge scores from preassessment to postassessment

| Wrong to right |

Right to right |

Right to wrong |

Wrong to wrong |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | p Value | ||

| Recommended by guidelines? | Community jury | 4 | (42) | 3 | (25) | 1 | (8) | 3 | (25) | 0.08 |

| Control* | 1 | (8) | 1 | (8) | 1 | (8) | 10 | (77) | ||

| How accurate is the PSA test? | Community jury | 6 | (50) | 4 | (33) | 1 | (8) | 1 | (8) | 0.03 |

| Control | 2 | (14) | 9 | (64) | 0 | (0) | 3 | (21) | ||

| List possible treatment options | Community jury | 2 | (17) | 7 | (58) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (17) | 0.6 |

| Control | 3 | (21) | 7 | (50) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (27) | ||

| List possible side effects of treatments | Community jury | 3 | (25) | 7 | (58) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (17) | 0.6 |

| Control | 3 | (21) | 7 | (50) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (27) | ||

*n=13 (1 missing).

PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Postassessment to 3-month follow-up assessment

The influence of the community jury experience was sustained at 3 months: men in the community jury group maintained their intention-to-screen score at 3 months (figure 2), whereas there was a slight increase in the control group's future intention-to-screen for prostate cancer. There was no further change in knowledge (table 5).

Table 5.

Changes in men's knowledge scores postassesment to follow-up assessment

| Wrong to right |

Right to right |

Right to wrong |

Wrong to wrong |

p Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | n | Per cent | |||

| Recommended by guidelines? | Community jury | 0 | (0) | 7 | (58) | 1 | (8) | 4 | (33) | 0.7 |

| Control* | 0 | (0) | 1 | (7) | 1 | (7) | 11 | (85) | ||

| How accurate is the PSA test? | Community jury | 0 | (0) | 10 | (83) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (17) | 0.1 |

| Control | 2 | (14) | 9 | (64) | 2 | (14) | 1 | (7) | ||

*n=13 (1 missing).

PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Community level questions

The men in the community jury voted unanimously (10/10) against a government campaign targeting the public about PSA screening for prostate cancer, and against a government organised invitation programme. Unprompted, the jury members instead suggested the government provide a campaign that targeted general practitioners to assist them to provide better quality and more consistent information to their patients on the benefits and harms of screening for prostate cancer using the PSA test.18

Non-protocol extension

Compared with their 3-month follow-up scores, the men from the control group who completed the second community jury also subsequently increased their self-report score of how informed they considered themselves (mean score increased from 2.2 to 3.7), and decreased their future intention to be screened for prostate cancer (mean score decreased from 8 to 2.8).

Discussion

Compared with men who received standard information, participants in a 2-day community jury considered themselves to be better informed about the benefits and harms of PSA screening and reduced their stated intention to participate in screening in the future. Although the process led to some men changing their minds about participating in PSA screening, others said they would continue to be tested; highlighting the individual nature of this decision and the need for informed consent.20

Yet, despite differences in the men's individual intentions to be screened for prostate cancer, the group was unanimous in opposing any government-sponsored community campaigns. Our findings demonstrate the capacity of a community jury to consider complex information on the harms and benefits of screening, and to distinguish individual from community choices. This echoes the findings of a New Zealand community jury on mammography screening13 which also indicated that community juries are able to differentiate between individual and public health needs.

All deliberative democracy methods rely on engagement of those who have an interest in the topic and agree to take part. The generalisability of our study findings may be limited by the uncertain representativeness of a jury of volunteers from the Gold Coast, Australia, who may be different in several ways to men in the wider Australian community. For example, 88% of our participants had already had at least one PSA test, implying that prior to the community jury they were more likely to be favourably disposed to PSA screening.

The authors considered PSA screening an appropriate topic for engaging middle-aged men because the data are equivocal and guidelines differ.2 7 8 However, we also acknowledge the limitations of these mass population studies. The median follow-ups of the ERSPC3 and PLCO4 trials (13 and 11 years) are not sufficient to reliably address long-term prostate cancer mortality and their respective methodologies have been criticised.21 This limitation may have impacted the community jury decision. Nevertheless, this pilot study does illustrate the potential of the community jury approach to instruct a cross-section of men of different ages, with different backgrounds and educational levels.

Whether and how the sampling and recruitment techniques affect community jury outcomes are important research questions yet to be examined. Other important methodological questions for community research include: what are the impacts on group decisions of normative (conformity to group thinking) or informational (discussion of facts) influences?22 and when and how in the deliberation process do community jury participants form their conclusions?

Our results have implications for clinical and public health practice. A large proportion of men have not been engaged in an evidence-informed discussion of the potential benefits and harms of screening prior to their physician ordering a PSA test;23 24 have not been asked about their screening preferences prior to a PSA screening test;25 and some doctors screen without a discussion.26 Alarmingly, a study conducted in the theatre waiting room on men waiting to undergo a transrectal ultrasound and prostate biopsy found that 8% were unaware of the fact that their primary care provider had conducted a PSA screening test.27 The current practice of PSA screening in asymptomatic men is not standardised. Our findings reinforce the importance of presenting the potential benefits and harms of PSA testing to men interested in being screened, primarily because such information will lead some men to change their mind, once fully informed. When practitioners are faced with the difficult situation of being asked to determine such a decision on behalf of their patient, in addition to considering their individual patient's history, concerns and priorities, it may be valuable to also have available information about community attitudes and concerns regarding screening.20

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jim Dickinson PhD FRACGP, Professor of Family Medicine, University of Calgary, Canada for kindly providing his scientific expertise as our scientific advisor in the community jury. He did not receive compensation for his contribution. They also thank Sir Iain Chalmers DSc, James Lind Initiative, Oxford, UK for his helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

Contributors: RT led the preparations and revisions of the manuscript, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the accuracy of the data analyses. PG and JD led the conception and design of the study, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and made substantial revisions to the manuscript. LR contributed to the study design and made substantial revisions to the manuscript. GM and RG contributed to the study design, interpretation of data and made significant revisions to the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a Bond University Vice Chancellor's Research Grant Scheme, an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (#1023791), and a NHMRC Screening and Test Evaluation Program (STEP) grant (#633033).

Competing interests: RT, JD, PG and GM received funding support from Bond University; RT, JD and PG also received funding support from an NHMRC Program grant (#633033); LR received funding support from an NHMRC funding grant (#1023197).

Ethics approval: The research project was approved by the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee (RO1570).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: In addition to the quantitative analysis reported in this paper, a qualitative analysis of the jury deliberations and recommendations was conducted and reported elsewhere and cited as ref. 18. Additional data is available by emailing the first author.

References

- 1.Katz MH. Can we stop ordering prostate-specific antigen screening tests? JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:847–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilic D, Neuberger MM, Djulbegovic M et al. . Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD004720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al. . Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 Years of follow-up. N Engl J Med 2012;366:981–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III et al. . Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:125–32. 10.1093/jnci/djr500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:120–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ et al. . Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2013;190:419–26. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. 8th edn East Melbourne, VIC: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urology Society of Australia and New Zealand PSA testing policy. http://www.usanz.org.au/uploads/29168/ufiles/USANZ_2009_PSA_Testing_Policy_Final1.pdf (accessed Apr 2013).

- 9.Benbassat J, Pilpel D, Tidhar M. Patients’ preferences for participation in clinical decision making: a review of published studies. Behav Med 1998;2:81–8. 10.1080/08964289809596384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S et al. . Do people want to be autonomous patients? Preferred roles in treatment decision-making in several patient populations. Health Expect 2007;10:248–58. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carman KL, Heeringa JW, Heil SKR et al. . The use of public deliberation in eliciting public input: findings from a literature review. (Prepared by the American Institutes for Research Under Contract No. 290–02–0009.) AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC070-EF Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abelson J, Eyles J, McLeod CB et al. . Does deliberation make a difference? Results from a citizens panel study of health goals priority setting. Health Policy 2003;66:95–106. 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00048-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul C, Nicholls R, Priest P et al. . Making policy decisions about population screening for breast cancer: the role of citizens’ deliberation. Health Policy 2008;85:314–20. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vries R, Stanczyk A, Wall IF et al. . Assessing the quality of democratic deliberation: a case study of public deliberation on the ethics of surrogate consent for research. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1896–903. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkin L, Paul C. Public good, personal privacy: a citizens’ deliberation about using medical information for pharmacoepidemiological research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:150–6. 10.1136/jech.2009.097436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Australian Cancer Council Factsheet: early detection of prostate cancer. http://www.cancer.org.au/content/pdf/Factsheets/Early_Detection_prostate-cancer-2013-revised.pdf (accessed Apr 2013).

- 17.Andrology Australia Factsheet: PSA testing. https://www.andrologyaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/Factsheet_PSA-Test.pdf (accessed Apr 2013).

- 18.Rychetnik L, Doust J, Thomas R et al. . A community jury on PSA screening: what do well-informed men want the government to do about prostate cancer screening? BMJ Open 2014;4:e004682 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staw BM. The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Acad Manage J 1981;6:577–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwig L, Glasziou P. Informed consent for screening by community sampling. Eff Clin Pract 2000;3:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Health and Medical Research Council. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in asymptomatic men: Evidence Evaluation Report. Canberra, ACT: National Health and Medical Research Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan MF, Miller CE. Group decision making and normative versus informational influence: effects of type of issue and assigned decision rule. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;53:306–13. 10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan ECY, Vernon SW, Ahn C et al. . Do men know that they have had a prostate specific antigen test? Accuracy of self-reports of testing at 2 sites. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1336–8. 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerra CE, Jacobs SE, Holmes JH et al. . Are physicians discussing prostate cancer screening with their patients and why or why not? A pilot study. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:901–7. 10.1007/s11606-007-0142-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman RM, Couper MP, Zikmund-Fisher BJ et al. . Prostate cancer screening decisions. Results from the National Survey of Medical Decisions (DECISIONS Study). Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1611–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volk RJ, Linder SK, Kallen MA et al. . Primary care physicians’ use of an informed decision-making process for prostate cancer screening. Ann Fam Med 2013:1:67–74. 10.1370/afm.1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan D, McCahy P. Patient knowledge about prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate cancer in Australia. BJU Int 2012:109(Sup 3):52–6. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.