Abstract

Introduction

Early identification (EI) and brief interventions (BIs) for risky drinkers are effective tools in primary care. Lack of time in daily practice has been identified as one of the main barriers to implementation of BI. There is growing evidence that facilitated access by primary healthcare professionals (PHCPs) to a web-based BI can be a time-saving alternative to standard face-to-face BIs, but there is as yet no evidence about the effectiveness of this approach relative to conventional BI. The main aim of this study is to test non-inferiority of facilitation to a web-based BI for risky drinkers delivered by PHCP against face-to-face BI.

Method and analysis

A randomised controlled non-inferiority trial comparing both interventions will be performed in primary care health centres in Catalonia, Spain. Unselected adult patients attending participating centres will be given a leaflet inviting them to log on to a website to complete the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) alcohol screening questionnaire. Participants with positive results will be requested online to complete a trial module including consent, baseline assessment and randomisation to either face-to-face BI by the practitioner or BI via the alcohol reduction website. Follow-up assessment of risky drinking will be undertaken online at 3 months and 1 year using the full AUDIT and D5-EQD5 scale. Proportions of risky drinkers in each group will be calculated and non-inferiority assessed against a specified margin of 10%. Assuming reduction of 30% of risky drinkers receiving standard intervention, 1000 patients will be required to give 90% power to reject the null hypothesis.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Commmittee of IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina P14/028. The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, national and international conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02082990.

Introduction

Risky drinking is a worldwide public health problem. In total, 74% of Europeans aged 15 years or older drink alcohol and 15% of them (58 million people) drink above the recommended level.1 Around the world, 3.8% of premature deaths and 4.6% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost are attributable to alcohol use.2

In Catalonia, one of five patients attending primary healthcare are risky drinkers.3 However, the proportion of people who access treatment out of those who need it varies from 4% (Germany) to 23% (Italy). In Spain, the percentage of the in-need population-accessing treatment is 15.3%.4 5

Early identification (EI) and brief intervention (BI) are among the most effective approaches for risky drinkers in primary healthcare.6 7 However, there is an important gap between research and clinical practice.8 Less than 10% of risky drinkers attended the primary healthcare benefit from BI.7 The main barriers in implementing EI and BI in primary care are time constraints, lack of financial incentives, insufficient training or absence of services to refer patient to and risk of upsetting patient.4 Web-based BIs (e-BIs) are an alternative to improve the implementation, acceptance and viability of BI and to overcome barriers that have hampered their use in daily practice.9 10 The provision of facilitated access by primary care professionals to an alcohol reduction website could significantly increase BI rates by offering a time-saving alternative to face-to-face intervention. Many studies have shown the efficacy of computer-based interventions in getting college students to reduce their alcohol consumption.11 12 The use of new technologies for mental health problems is becoming common in primary care, as, for example, in smoking cessation.13 A review of trials of computer-based interventions in college drinkers found them to be more effective than no treatment and as effective as alternative treatment approaches.11

Down Your Drink (DYD; http://www.downyourdrink.org.uk) is an online intervention developed in UK based on BI, cognitive–behavioural therapy, self-control therapy and motivational interviewing. An online trial of DYD indicated potentially significant reductions in alcohol consumption and risky drinking behaviours in participants who used the trial websites,14 and, following this, a number of initiatives have been initiated to test the acceptability and effectiveness of facilitating access to websites of this kind in primary care settings. The EU-funded ODHIN trial15 currently underway in five European countries is designed to determine the impact of facilitated access on levels of implementation of BIs by primary care practitioners. The EFAR FVG study in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region in Northern Italy16 has been designed to test the effectiveness relative to face-to-face intervention of facilitated access to an Italian version of DYD by general practitioners. This trial involves 40 general practices and has recruited more than 500 patients.16 EFAR-Spain is based on the EFAR-FVG study, but has the following differences: (1) participation is open to doctors as well as nurses; (2) primary healthcare centres are constituted by a team of different professionals (nursing, medicine, social work, administration, etc); and (3) the website has not only been translated but also adapted to Spanish culture.

In Catalonia, no efficacy studies on e-BI exist. However, some limited e-BI initiatives have been undertaken in order to support the implementation of the ‘Beveu Menys’ programme,17 a programme aimed at implementing EI and BI by, among other strategies, identifying a Network of Alcohol Referents in Primary Health Care (XaROH) throughout the territory and providing continuous training and support to them. An online quantity–frequency tool was developed and promoted to be used as a general population awareness-raising tool with promising results.18 Recently, in the context of the ODHIN project,19 an e-BI tool, adapted from Drinkers Check-Up,20 was used to test facilitated access only, but results are still under analysis.

We present the protocol of a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (1:1) which aims to test non-inferiority of an e-BI for risky drinkers against a traditional face-to-face BI delivered by a primary healthcare professional (PHCP; nurse or general practitioners (GPs)).

Method

Trial design: A randomised non-inferiority controlled trial in primary care comparing facilitated access to a website for risky drinkers against a standard face-to-face BI. With the exception of the non-experimental intervention, all components of the study will be administered online to patients. Patients will be actively encouraged by their PHCP to access the application, which is available on the website of the programme ‘Alcohol y Salud’ (http://www.alcoholysalud.cat), and will be provided with a unique registration code.

The trial website is a Spanish adaptation of the English version of http://www.DownYourDrink.org.uk (DYD) developed in the UK, which includes modules for all the key trial components including screening, consent, assessment, randomisation and follow-up. It also incorporates the alcohol reduction website for the patients in the experimental group. The site has been adapted from the http://www.DownYourDrink.org.uk website developed for the DYD-RCT (randomised controlled trial).14 Details of DYD and the psychological theory that underpinned its development have been reported elsewhere.21 Country-specific information such as recommended guidelines for alcohol intake, definitions of standard drinks and alcohol-related laws will be included. The website also incorporates a menu-driven facility to enable PHCP to customise automated messages to patients, for example, by adding photographs and pre-recorded messages. The personalised messages will appear to each patient using the log-in code provided by that practitioner.

Practitioner recruitment, training and incentives: Recruitment will be based on the XaROH network. A 3 h seminar on new technologies, and EI and BI, introducing the trial, will be offered to all members of the XaROH, and those attending will be invited to sign up for the trial. In addition, several advertisements will be posted on the ‘Beveu Menys’ platform offering participation in the trial. In selecting practices, preference will be given to those with at least 5000 registered patients. Those practices that are selected as participants will be required to undergo a 1-day training programme. The training has four steps: (1) introduction to trial; (2) familiarisation with website; (3) update about EI and BI; and (4) practice in EI and BI (role-playing). Finally, participants will be encouraged to use the website and to tailor-make patient messages. Participating PHCPs will receive a financial incentive of €20 per patient recruited to the trial.

Patient eligibility

Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 years or older attending the participating practices during the study period.

Exclusion criteria: those suffering from severe psychiatric disorders, serious visual impairment or terminal illness, those having inadequate command of the Spanish or Catalan language, or Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) ≥18 in baseline assessment. Excluded patients will be referred to PHCP to consider other interventions.

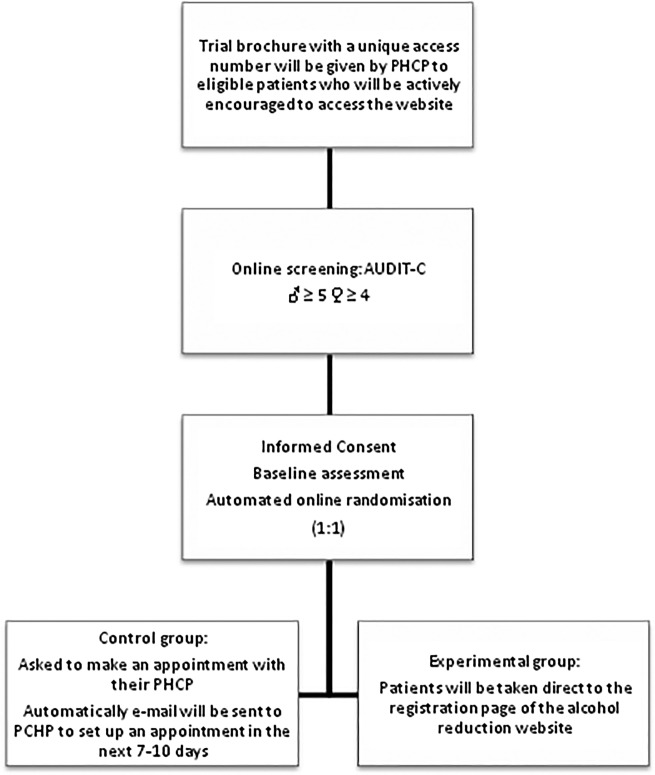

Screening and Consent: Eligible patients will be given a trial brochure by their GP or nurse and actively encouraged to access the specially designed website ‘http://www.alcoholysalud.cat’. Each brochure will include a unique access number that will enable the patient to log on to the website. All patients who access the website will be informed about the trial and asked to complete an online form confirming that they do not meet any of the exclusion criteria and inviting them to complete the online consent module. They will then be asked to complete an online version of the short AUDIT-C.22 Cut-off points for the purpose of the trial will be 4 for women and 5 for men. Those screening negative will be informed that their responses indicated acceptable drinking patterns according to national guidelines and will be encouraged not to increase their alcohol consumption. Those scoring at or above the cut-off point will be invited by tailored online message from their PHCP to take part in the study as they present a risky drinking pattern (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart: recruitment process (PHCP, primary healthcare professional; AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test).

Baseline assessment includes a demographic questionnaire (age, gender, level of education and occupation), the 10-question Alcohol Use Disorder Test Spanish version23 and D5-EQ D5, the quality-of-life questionnaire, validated in Spanish versions.24 25

Randomisation and intervention: Those patients who complete the baseline assessment will undergo automated online randomisation by a specific module of website (1:1). Experimental group patients will be taken direct to the registration page of the alcohol reduction website ‘Alcohol y Salud’ (http://www.alcoholysalud.cat), where they will receive a personalised message from the PHCP who gave them the brochure with tailored feedback about their responses to the alcohol questionnaires. Personalised online messages from their PHCP will inform the patients of the importance of adopting healthy drinking choices and will encourage them to spend at least 15 min engaging with the alcohol reduction website in the first instance. Each participating PHCP will have access to the section of website enabling them to personalise their messages (see ‘Trial website’). Patients will also receive an email 1 week later encouraging them to log on again to review their alcohol consumption. Online messages will also encourage the patients to discuss their website experience when they next see their PHCP.

Control group patients will receive an online message asking them to make an appointment to see their PHCP to discuss their drinking, and an automatically generated email will also be sent to their PHCP to set up a visit in the next 7–10 days. At the appointment, the patient will receive a face-to-face brief motivational interview with the following components: (1) assessment of the motivation to change; (2) assessment of the stage of change; (3) advice on changing drinking pattern; (4) empathy; and (5) capacity building.

Non-attenders will be offered up to three additional recalls.

Follow-up assessment

Follow-up will take place at 3 and 12 months after randomisation, and each assessment will consist of the following instruments:

The 10-question AUDIT validated Spanish version.

The EQ-5D-5 self-complete Spanish version (http://www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-products/eq-5d-5l.html)

Up to three attempts by email will be made to ensure follow-up. The last attempt will be made by the PHCP by letter, phone or in person. There are no restrictions to concomitant care.

Data security and storage

In order to ensure the security of personal data of participating patients and healthcare professionals, the site will be hosted on its own separate server, which will be maintained and monitored closely throughout the project.

All communication between participants or PHCP and the web server will take place over an encrypted ‘http’ connection.

Similarly, any interaction with the web server by research staff or technical maintenance staff will be over a secure connection.

Access to the website and web server will be restricted to a small number of research and technical staff. The data will be collected and stored in accordance with best practices. All outcome data will be anonymised and identifiable only by a patient's unique ID and code.

Access to the final trial data set will be limited to the research team.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome will be the proportion of patients classified as risky drinkers by the AUDIT-10 at month 3 after the randomisation.

Aiming to assess the non-inferiority of facilitated access compared with standard face-to-face intervention, the proportion of risky drinkers in both groups will be compared using generalised non-linear mixed models. Non-inferiority will be considered if the difference between groups is not greater than 10%. Based on an anticipated reduction of 30% in the proportion of risky drinkers in control group and an overall attrition of 10%, it is calculated that 500 patients in each group will be needed to reject the null hypothesis (facilitated access is inferior to standard face-to-face intervention) with 90% power.

No interim analysis is planned.

All analysis details will be set up in a predesignated statistical analysis plan before the data are accessed.

Impact on screening rates of facilitated access to the website

It is hypothesised that the provision of facilitated access to the website will lead to an increase in alcohol screening rates in the trial practices. A substudy will therefore be carried out comparing pre-trial and post-trial alcohol screening rates in the participating practices, calculated on the basis of entries in the electronic care records of patients attending over a 6-month period. Further comparison will be carried out with a matched control group of practices that did not participate in the EFAR trial.

Discussion

The trial has several strengths. The research team includes international expertise and the protocol benefits from extensive experience gained through the EFAR FVG trial, which has recruited well and achieved high rates of follow-up. Recruitment of PHCPs will be achieved using an established, structured and well-trained network that has been involved in previous alcohol projects including ODHIN, PHEPA and Beveu Menys. The trainers have also had extensive experience of SBI training, and the network includes nursing as well as medical professionals, thus offering the potential to recruit a wide range of patients. It is the first trial testing the utility of facilitated access in Spain. It is carried out in the context of the daily work of PHCPs and can be embedded in the alcohol SBI activities undertaken in Catalonia so far. It is a natural evolution of the work being done and if results are positive such a website could be included in the future in the personal file of PHCPs and promoted as a complementary tool throughout all primary healthcare centres.

There may be initial professional resistance to engaging with facilitated access activity as the trial will be carried out by PHCPs with little or no experience of promoting the use of the internet for the delivery of alcohol screening and BI. However, we have taken account of this by using conservative estimates in calculating the anticipated facilitated access rates, and will offer training to all the participating PHCPs in order to overcome usability problems. The current version of the website has been well-accepted by Italian professionals and patients,26 and all the professionals participating in the EFAR Spain trial will be invited to familiarise themselves with the website prior to the start of the trial. Furthermore, the research team will provide continuous support though email, an internet forum and by telephone. Support materials will also be provided, including Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), feedback data and alcohol-related problems management documents.

It is likely that a degree of selection bias will result from increased participation by younger and better educated patients likely to be more familiar with the internet. However, baseline assessment will provide data on a range of demographics, enabling comparisons to be made with the general population. While it is also possible that the trial will select more motivated participants who are especially concerned about their alcohol use, randomisation should ensure that these effects are equally distributed between the intervention and control groups.

In conclusion, while the trial poses significant challenges, it also has the benefit of international experience and expertise and delivery by PHCPs from a structured network with extensive previous experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the following institutions: University College of London (UCL), Institut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Hospital Clínic i Universitari de Barcelona and the Program on Substance Abuse (Public Health Agency, Government of Catalonia). Technical support is provided by Daniel Berzon and Richard McGregor from Codeface. Special acknowledgments to all professionals participating in the field work (EFAR Research Group) and members of XaROH.

Footnotes

Collaborators : EFAR-Catalonia (Spain) group.

Contributors: HL-P, AG, LS and PW designed the study and drafted the article. Other authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work has been funded by project PI042924 integrated in the National R+D+I and funded by the Carlos III Health Institute-Deputy General Assessment and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). (http://www.isciii.es).

Competing interests: AG has received honoraria, research grants and travel grants from Lundbeck Janssen, Pfizer, Lilly, Abbvie D&A Pharma, and Servier. HL-P has received travel grants from Lundbeck, Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Rovi and Esteve.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved on P14/028 by the Ethics Committee, IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina. Any amendment protocol would be communicated to the ethics committee and published on clinicaltrials.gov.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Gual A, Anderson P. A new AMPHORA: an introduction to the project Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance. Addiction 2011;106(Suppl 1):1–3. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S et al. . Alcohol and Global Health 1 Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009;373:2223–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segura Garcia L, Gual Sole A, Montserrat Mestre O et al. . Detection and handling of alcohol problems in primary care in Catalonia. Aten Primaria 2006;37:484–8. 10.1157/13089078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolstenholme A, Drummond C, Deluca P, et al. Report on the mapping of European need and service provision for early diagnosis and treatment of alcohol use disorders. Deliverable 2.5, Work Package 6. The public health impact of individually directed brief interventions and treatment for alcohol use disorders in European countries. http://amphoraproject.net/w2box/data/Deliverables/AMPHORA_WP6_D2.5.pdf.

- 5.Drummond C, Wolstenholme A, Deluca P et al. . Alcohol interventions and treatment in Europe. In: Anderson P, Braddick F, Reynolds J, Gual A, eds. Alcohol policy in Europe: evidence from AMPHORA. The AMPHORA project. 2nd edn 2013; Chapter 9, pp 87–92. http://www.amphoraproject.net [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaner EF, Dickinson HO, Beyer F et al. . The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009;28:301–23. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Alcohol and Global Health 2 effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 2009;373:2234–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheffield Uo. Guidance: Prevention and early identification of alcohol use disorders in adults and young people. 2009.

- 9.Shakeshaft A, Fawcett J, Mattick RP et al. . Patient-driven computers in primary care: their use and feasibility. Health Educ 2006;106:400–11. 10.1108/09654280610686612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shakeshaft AP, Frankish CJ. Using patient-driven computers to provide cost-effective prevention in primary care: a conceptual framework. Health Promot Int 2003;18:67–77. 10.1093/heapro/18.1.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Elliott JC et al. . Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2009;104:1807–19. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Champion KE, Newton NC, Barrett EL et al. . A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers or the internet. Drug Alcohol Rev 2013;32:115–23. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Free C, Knight R, Robertson S et al. . Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:49–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60701-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace P, Murray E, McCambridge J et al. . On-line randomized controlled trial of an internet based psychologically enhanced intervention for people with hazardous alcohol consumption. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e14740 10.1371/journal.pone.0014740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ODHIN. The ODHIN (Optimizing delivery of health care interventions) project website. 2013. http://www.odhinproject.eu/

- 16.Struzzo P, Scafato E, McGregor R et al. . A randomised controlled non-inferiority trial of primary care-based facilitated access to an alcohol reduction website (EFAR-FVG): the study protocol. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catalunya Gd. Programa “Beveu menys” 2014; http://www20.gencat.cat/portal/site/canalsalut/menuitem.41e04b39494f1be3ba963bb4b0c0e1a0/?vgnextoid=e0684fb23d564310VgnVCM2000009b0c1e0aRCRD&vgnextchannel=e0684fb23d564310VgnVCM2000009b0c1e0aRCRD&newLang=es_ES

- 18.Segura L, Torres M, Vidal A et al., eds. Utility of internet based assessment tool to measure alcohol consumption. Oral Communication on 10th INEBRIA Conference 2013. http://www.inebria.net/Du14/pdf/calculadora_inebria_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keurhorst MN, Anderson P, Spak F et al. . Implementing training and support, financial reimbursement, and referral to an internet-based brief advice program to improve the early identification of hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care (ODHIN): study protocol for a cluster randomized factorial trial. Implement Sci 2013;8:11 10.1186/1748-5908-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker's check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. J Subst Abuse Treat 2005;28:159–69. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linke S, McCambridge J, Khadjesari Z et al. . Development of a psychologically enhanced interactive online intervention for hazardous drinking. Alcohol Alcohol 2008;43:669–74. 10.1093/alcalc/agn066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez A, Conde A, Santana JM et al. . Diagnostic usefulness of brief versions of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) for detecting hazardous drinkers in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol 2005;66:305–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contel Guillamon M, Gual Sole A, Colom Farran J. Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): translation and validation of Catalan and Spanish. Test para la identificacion de transtornos por uso de alcohol (AUDIT): Traduccion y validacion del audit al Catalan y Castellano. Adicciones 1999;11:337–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badia X, Roset M, Montserrat S et al. . [The Spanish version of the EuroQol: a description and its applications. European Quality of Life scale]. Med Clin (Barc) 1999;112(Suppl 1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badia X, Schiaffino A, Alonso J et al. . Using the EuroQol 5-D in the Catalan general population: feasibility and construct validity. Qual Life Res 1998;7:311–22. 10.1023/A:1008894502042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace P, Struzzo P, Della Vedova R et al. . Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial of primary care based facilitated access to an alcohol reduction website (EFAR-FVG). Addict Sci Clin Pract 2013; 8(Suppl 1):A83. http://www.ascpjournal.org/content/8/S1/A83 10.1186/1940-0640-8-S1-A83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.