Abstract

Hijamah (a well-known Prophetic complimentary treatment) has been used for centuries to treat various human diseases. It is considered that this traditional treatment (also known as wet cupping) has the potential to treat many kinds of diseases. It is performed by creating a vacuum on the skin by using a cup to collect the stagnant blood in that particular area. The vacuum at the end is released by removing the cup. Superficial skin scarification is then made to draw the blood stagnation out of the body. This technique needs to be performed in aseptic conditions by a well trained Hijamah-physician. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) had described Hijamah as the best treatment humans can have. This novel treatment methodology has been successfully used as cure for numerous diseases including skin diseases. In this case report, we discuss about the application of this method in the treatment of psoriasis (an autoimmune skin disease). Results illustrated that with Hijamah, disease can not only be controlled but can be brought to a nearly complete remission.

Keywords: Hijamah, Sunnah, Aameen, Psoriasis

1. Background

Psoriasis is T-cell mediated autoimmune inflammatory skin disease characterized by skin surface inflammation, epidermal proliferation, hyperkeratosis, angiogenesis, and abnormal keratinization (Rahman et al., 2012). At present, nearly 3% of world population is affected by this disease (Rahman et al., 2012; Danielsen et al., 2013). It has genetic manifestations and the risk of acquiring the disease is found in almost half of the siblings if both parents had it. Risk drops to less than a quarter if one of the parents had psoriasis (Psoriasis, 2014). Psoriasis is not limited to any particular area but can range from a minor spot on the skin to the entire skin (Psoriasis, 2014; Schön and Boehncke, 2005).

T-Cell activated inflammatory response has been found to be responsible as the main pathophysiology behind psoriasis (Psoriasis and Law, 2011; Nickoloff et al., 1999). Once T-Cells are activated, they migrate both from lymph nodes and systemic circulation to the skin. These T cells further activate various cytokines that induce the pathological changes of psoriasis (Nickoloff et al., 1999; Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). These cytokines include but not limited to TNF-α, IL-8, IL-12 and macrophage inflammatory protein 3α (MIP-3α) Danielsen et al., 2013; Psoriasis and Law, 2011; Biasi et al., 1998. More notably, research for better disease understanding and development of curable approach for psoriasis received much attention in recent time as new studies showed that psoriasis is an important risk factor in many diseases. Lately, it was found that psoriasis is an independent risk factor for diabetes (type 2 DM) and cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia (Wu et al., 2008; Azfar et al., 2012). Moreover, other comorbidities commonly associated with psoriasis are arthritis, depression, insomnia and obstructive pulmonary disease (Wu et al., 2008). Available therapies used for the management of psoriasis include topical and systemic medications, phototherapy and combination of both. Topical medications usually include Vitamin D, calcipotriol, corticosteroids (used systemically as well), dithranol and retinoids. Systemic therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine and antibody therapy. Phototherapy includes radiation therapy and Psoralen plus ultraviolet therapy. All these therapies have potential limitations such as poor efficacy, rapid relapse of disease, drug and biological associated potential side effects (for example; hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, organ toxicity and immunosuppression), hyperlipidaemia, growth suppression, adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s syndrome, femoral head osteonecrosis, and possible congenital malformations (Rahman et al., 2012; Menter et al., 2009; Stanway, 2013; Australian Medicines Handbook, 2013).

Hijamah (wet cupping), is an effective treatment for many diseases (Farhadi et al., 2009). Its efficacy to treat the non specific lower back pain has already been established (Farhadi et al., 2009). It was proven as a safe and better alternative therapy to the usual allopathic medical care (AlBedah et al., 2011; Ahmed et al., 2005). Some studies have found the effectiveness of wet cupping combined with drug treatment superior to the medical treatment alone (AlBedah et al., 2011). Beside this, wet cupping therapy has also got the immune-modulatory effects (Ahmed et al., 2005). Its ability to modulate the immune system has well been established. It was thus postulated that this aspect of Hijamah therapy can be used to treat other immune related diseases as well.

2. Case history

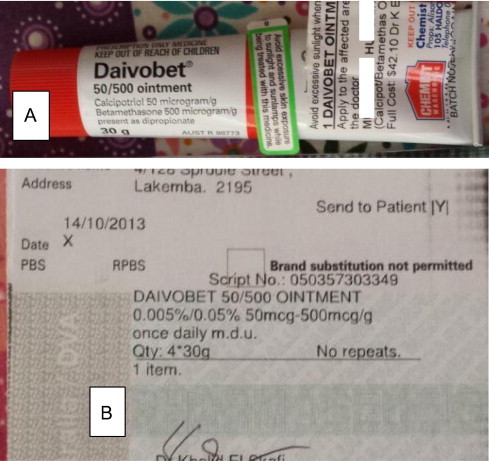

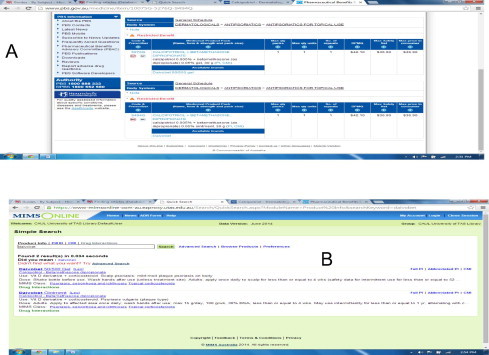

Mr. Muhammad H. (MH) is a 30 year old male working and living in Australia. He works as Incident Management Analyst and also does the mechanical work on his car by himself as a hobby. Three years ago, when he was helping to unload a car engine from a truck, his right front leg scratched (a size less than 5 cent coin), however, he was not worried at-all at that time. After few weeks, he noticed that few bubble appeared on the affected leg, which burst out and left a mark with slight itching. He went to the doctor and was prescribed steroid cream. He started using the cream and the spots disappeared gradually. But this was not the end of story. Spots/lesions kept appearing and he kept using the cream, which not only cost him high but also resulted in skin thinning followed by easy bruising even with minimum shear. This made him really worried. Few days later, the lesions spread to the other leg, arm, back and the head (Fig. 1A–D). He visited the doctor and was again prescribed the high potency steroid combination cream namely Daivobet (Fig. 2A and B). This combination is used to treat psoriasis (Fig. 3A and B). The results were same as before i.e. as long as the cream was being used, the lesion would go away but as soon as the cream was stopped the problem would come back. He noticed that even during the regular use of cream, the incidence of appearing of the new lesion was unaffected, i.e. the steroid cream was not effective in preventing the new lesions. The situation was annoying and he finally was referred to the skin specialist for further review. The specialist ordered the biopsy of the lesion and kept him on steroid cream. The biopsy report came after few weeks and it failed to find any abnormality. This made him even more worried realizing that he is suffering from such a bad and progressive skin condition and doctors failed to establish any definite diagnosis. The plight was that according to doctors, there is no cure for the disease and the condition could only be managed rather slowed by the continuous use of steroid cream or other drugs. Moreover there is no option to avoid the side effects of medical therapy. Further, the cost of the cream was high i.e. 42.10 Australian dollars per four tube (Fig. 2A). Moreover this medicine is available through a complex prescribing procedure (Fig. 3A). Later on, the patient visited his home country and consulted a skin specialist, who confirmed the disease as psoriasis and advises him some other alternative drugs other than steroids. But the problem was same: no complete remission and non tolerable side effects. Finally he contacted the qualified Hijamah therapist and was given advice not to worry about it, as the Hijamah is an effective therapy for many diseases including psoriasis, by the will of Allah. A Hadiths says to the nearest meaning “indeed the best of treatments you have is Hijamah” (Bukhari, xxxx).

Figure 1.

Images of patient’s limbs before Hijamah treatment: (A) Right leg (near the knee); (B) Lower left leg; (C) Lower right leg; and (D) Left leg (near the knee).

Figure 2.

Images of Daivobet packing (A) and doctor prescription (B).

Figure 3.

Information regarding Daivobet on the web: (A). PBS scheme showing the cost of the cream, indication of use and the process of obtaining the cream on PBS and (B) MIMS online drug information database.

3. Methodology, results and discussion

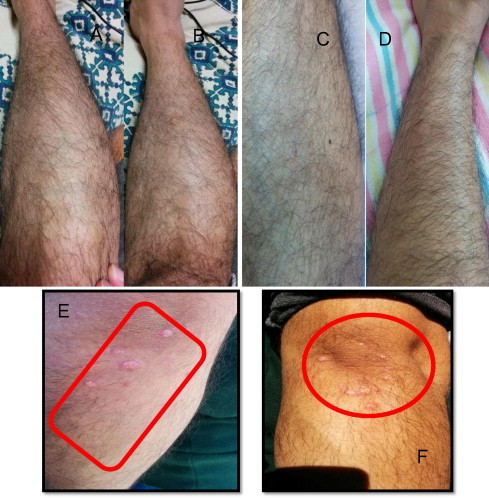

Mr. MH was counseled and was given advice to seek help of ALLAH (the Creator) and the Hijamah therapy was started. At this point the severity of the disease was examined using the online tools like PASI (psoriasis area severity index) and it was found to be 2. The wet cupping sessions (using the sterile plastic cups to create a negative pressure on the skin and then performing the superficial skin incision to draw the stagnant blood) were designed to be performed once a week on the basis of diagnosis of the disease as psoriasis. He was advised to have minimum seven sessions to completely get rid of the disease. Hijamah was started and two days after the first session, lesions started to disappeared and reduced both in size and number. The patient continued for further two sessions and more than 90% of disease had gone. However, the patient could not continue further sessions despite his willingness due to his extreme business. It has been six months after the last session and all his lesions disappeared completely (Fig. 4A–D), and no itching is felt anywhere on the skin. The patient has not used any other type of therapy after that. Also no new lesion appeared anywhere except for some lesions at below his elbow after 6 months (Fig 4E and F). One possible reason for appearance of new lesions could be the incomplete treatment as the patient received only three sessions instead of initially advised schedule of seven sessions.

Figure 4.

Images of patient’s limbs after Hijamah treatment showing the absence of psoriatic lesion except on elbow. (A) Right leg (near the knee); (B) Left leg (near the knee); (C) Lower right leg; (D) Left lower leg; (E) Left elbow; and (F) Right elbow.

As this case report is not a conclusive evidence for the effectiveness of Hijamah for the all types of psoriasis, yet reasonably demonstrates the efficacy of Hijamah in treating psoriasis. More research and trials are needed to fully elucidate the effectiveness of Hijamah for all types of psoriasis with varying degrees of severity.

4. Conclusion

Hijamah has been used for centuries to treat human diseases. It is considered that this traditional treatment (also known as wet cupping) has the potential to treat many kinds of diseases. Its role in this regard has been greatly emphasized by our prophet Muhammad (PHUH), not only verbally but practically as well. This case study puts some light on the effectiveness of Hijamah to treat psoriasis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist in this case report.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the Scientific Chair of Yousef Abdul Latif Jameel of Prophetic Medical Applications, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia for support in Hijamah research project.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Rahman, M., Alam, K., Zaki Ahmad, M., Gupta, G., Afzal, M., Akhter, S., Anwar, F., 2012. Classical to current approach for treatment of psoriasis: a review. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Immune, Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders) 12(3), 287–302. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Danielsen K., Olsen A.O., Wilsgaard T., Furberg A.S. Is the prevalence of psoriasis increasing? A 30-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1303–1310. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psoriasis, Meffert J., 2014. Available from: <http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1943419-overview#aw2aab6b2b2>.

- Schön M.P., Boehncke W.-H. Psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352(18):1899–1912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver W. Psoriasis, Law, R., 2011. In: Edmonson MWaKG, (Eds.), Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiological Approach. eighth ed. McGraw-Hill Medical, NJ, USA, pp. 1693–1706.

- Nickoloff B.J., Wrone-Smith T., Bonish B., Porcelli S.A. Response of murine and normal human skin to injection of allogeneic blood-derived psoriatic immunocytes: detection of T cells expressing receptors typically present on natural killer cells, including CD94, CD158, and CD161. Arch. Dermatol. 1999;135(5):546–552. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.5.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati C., Ameglio F. Cytokines in psoriasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1999;38(4):241–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasi D., Carletto A., Caramaschi P., Bellavite P., Maleknia T., Scambi C. Neutrophil functions and IL-8 in psoriatic arthritis and in cutaneous psoriasis. Inflammation. 1998;22(5):533–543. doi: 10.1023/a:1022354212121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Mills D., Bala M. Psoriasis: cardiovascular risk factors and other disease comorbidities. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(4):373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azfar R.S., Seminara N.M., Shin D.B., Troxel A.B., Margolis D.J., Gelfand J.M. Increased risk of diabetes mellitus and likelihood of receiving diabetes mellitus treatment in patients with psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. 2012;148(9):995–1000. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menter A., Korman N.J., Elmets C.A., Feldman S.R., Gelfand J.M., Gordon K.B. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 3. Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009;60(4):643–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanway A., DermNet, N.Z., 2013 NZDSI.: 2012; Available from: <http://www.dermnetnz.org/scaly/flexural-psoriasis.html>.

- Australian Medicines Handbook, 2013. Australian Medicines Hand Book Pty. Ltd., Adelaide

- Farhadi K., Schwebel D.C., Saeb M., Choubsaz M., Mohammadi R., Ahmadi A. The effectiveness of wet-cupping for nonspecific low back pain in Iran: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther Med. 2009;17(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlBedah A., Khalil M., Elolemy A., Elsubai I., Khalil A. Hijama (cupping): a review of the evidence. Focus Altern. Complement. Ther. 2011;16(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S.M., Madbouly N.H., Maklad S.S., Abu-Shady E.A. Immunomodulatory effect of bloodletting cupping therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2005;12(2):39–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahih Bukhari, Volume 7, Book 71, Number 599. Available from: <http://www.sahih-bukhari.com/Pages/Bukhari_7_71.php>.