Abstract

Exposure to the agricultural work environment is a risk factor for the development of respiratory symptoms and chronic lung diseases. Inflammation is an important contributor to the pathogenesis of tissue injury and disease. Cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating lung inflammatory responses to agricultural dust are not yet fully understood. We studied the effects of poultry dust extract on molecular regulation of interleukin-8 (IL-8), a proinflammatory cytokine, in A549 and Beas2B lung epithelial and THP-1 monocytic cells. Our findings indicate that poultry dust extract potently induces IL-8 levels by increasing IL-8 gene transcription without altering IL-8 mRNA stability. Increase in IL-8 promoter activity was due to enhanced binding of activator protein 1 and NF-κB. IL-8 induction was associated with protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation and inhibited by PKC and MAPK inhibitors. IL-8 increase was not inhibited by polymyxin B or l-nitroarginine methyl ester, indicating lack of involvement of lipopolysaccharide and nitric oxide in the induction. Lung epithelial and THP-1 cells share common mechanisms for induction of IL-8 levels. Our findings identify key roles for transcriptional mechanisms and protein kinase signaling pathways for IL-8 induction and provide insights into the mechanisms regulating lung inflammatory responses to organic dust exposure.

Keywords: chemokine, lipopolysaccharide, lung inflammation

agricultural workers are exposed to high levels of airborne dust in their work environments, containing microbial pathogens, bioactive microbial constituents such as endotoxin, β-glucans, and peptidoglycan, as well as ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and methane (10, 23). Exposure to agricultural dust is a risk factor for the development of respiratory symptoms and chronic lung diseases (53, 58). Acute exposure to organic dust causes clinical symptoms such as cough, fever, chills, and malaise and is associated with inflammatory responses characterized by increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, neutrophils, and macrophages in the respiratory tract (26–28). Long-term exposure to agricultural dusts is associated with increased occurrence of chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (17, 36), a conglomeration of respiratory symptoms and diseases. Frequent exposure to animal dust dampens inflammatory responses attributable to adaptation (42, 56), but recurrent inflammation and injury may be responsible for declines in lung function and development of chronic lung diseases. Acute and chronic exposures of experimental animals to animal facility dust are associated with recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages into the lung and lung pathology similar to that in humans exposed to animal facility dust (9, 16, 43). In vitro exposure of macrophages and lung epithelial cells to animal facility and agricultural dust extracts increases production of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 (40, 46, 61).

The respiratory epithelium plays important roles in the propagation and modulation of host inflammatory responses to pathogens and particulates via production of immunomodulatory agents such as cytokines and surfactant (5, 35). Alveolar macrophages play central roles in the control of inflammatory responses through phagocytosis of foreign agents and particulates and production of cytokines. IL-8, a proinflammatory cytokine of the C-X-C chemokine family, is a potent chemoattractant and an activator of neutrophils and is implicated in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic lung diseases (37). IL-8 also has a wide range of effects on T cells, monocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. To date, a majority of studies on the effects of animal facility dust on lung inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo has focused on the understanding of the effects of swine facility dust. However, there appears to be a lack of information of the effects of other animal dusts on lung inflammatory responses and molecular mechanisms underlying such responses.

Poultry production in the United States and elsewhere has increased rapidly in recent years, and the combined value of poultry production in the United States was valued at $38.1 billion in 2012 (1). The poultry industry in the United States employs over 250,000 workers (2). Workers in the poultry production industry are exposed to significantly higher levels of total dust, endotoxin, total bacteria, total fungi as well as ammonia and carbon dioxide compared with workers in the swine production industry (29, 45). The levels of total dust and endotoxin in the poultry production environment were found to be at 7–20.3 mg/m3 and 250 endotoxin U/m3, respectively, which significantly exceeds the Threshold Limit Value set by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) and the suggested occupational health guidelines (15). Poultry workers have a higher prevalence of lower and upper respiratory symptoms and lower baseline lung function compared with workers in swine, cotton, and animal feed industries (25, 45, 53). As little as 3 h of exposure of naïve human volunteers to a poultry environment caused bronchial responsiveness and increase in IL-6 levels in nasal lavage fluid (26). Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, chronic bronchitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and occupational asthma are some of the diseases that are commonly found in poultry production workers (25, 26, 57).

Despite the high prevalence and severity of acute and chronic respiratory symptoms and lung diseases in poultry workers and the rapid expansion and economic impact of poultry production on United States agriculture, there is very little information on mechanisms underlying lung cellular and molecular responses to poultry dust. Thus the objective of our study was to understand molecular mechanisms of induction of IL-8 expression by aqueous extracts of poultry dust in A549 alveolar and Beas2B bronchial epithelial and THP-1 monocytic cells to better understand lung inflammatory responses.

We found that poultry dust extract is a powerful inducer of IL-8 expression in A549 alveolar and Beas2B bronchial epithelial cells as well as in THP-1 monocytic cells. IL-8 induction was due to an increase in gene transcription and not due to increase of mRNA stability. IL-8 induction was associated with activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and sensitive to pharmacological inhibition of PKC and MAPKs. Dust extract induced NF-κB and activator protein 1 (AP-1) DNA-binding activities, and IL-8 induction was dependent on NF-κB and AP-1 binding to their sites on IL-8 promoter. Studies using chemical inhibitors indicated that dust extract induction of IL-8 was not attributable to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) present in dust or mediated via nitric oxide (NO).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of dust extract.

Settled broiler poultry dust was collected at 8 wk of animal growth from the poultry facility of Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas. It is an indoor facility, where the chickens are floor raised; that is a standard practice for the industry in the United States. The dust was collected into sterile plastic tubes and stored at −70°C until use. Dust extract was prepared by incubating dust at a ratio of 1:10 (wt/vol) in serum-free F12 K medium containing penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml) in an ultrasound water bath for 10 min at room temperature. The mixture was periodically agitated during incubation, and the suspension was first cleared by centrifugation at 800 g for 5 min at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered using a 0.2-μm syringe filter, and the filtrate was divided into aliquots and stored at −20°C. The concentration of this extract was arbitrarily considered as 100%. Protein concentration of dust extracts was in the range of 0.2–0.4 mg/ml.

Determination of endotoxin, muramic acid, and ergosterol levels.

Endotoxin content in dust extracts was determined using the recombinant factor C assay (Lonza) as described previously (48). Endotoxin content was quantified in relation to United States Reference Standard EC-6 and reported as endotoxin units per milligram of protein of dust extract. Muramic acid, a marker for peptidoglycan, and ergosterol were determined by gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy as described previously (41). Samples were quantified with an HP 5890 series II Plus gas chromatograph equipped with an HP-5MS column (Hewlett-Packard) and HP Mass Selective Detector.

Cell culture.

A549 (ATCC CCL185) lung cells were grown on plastic culture dishes in F12 K medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Beas2B (ATCC CRL 9609) lung cells were grown on plastic culture dishes coated with fibronectin, bovine type 1 collagen, and bovine serum albumin in LHC 9 medium. THP-1 cells (ATCC TIB-202), a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line, were grown in suspension culture in plastic tissue culture dishes in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal bovine serum. All cell culture media contained 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B. Cells were placed in serum-free media overnight (16–18 h) before treatment with dust extract.

Cell viability.

Cell viability was determined using CellTiter96 Aqueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay kit (Promega). The kit measures the conversion of [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt] into a formazan product by metabolically active cells.

RNA isolation, Northern blotting, and quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA from cells was isolated using TRI-Reagent (Molecular Research Center), and Northern blotting analysis was performed as described previously (7). For determination of RNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR, RNA was first treated with DNase (Turbo DNA-free kit, Ambion) and cDNA synthesized. IL-8 and 18S rRNA levels were quantified by TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) (IL-8 assay ID: Hs00174103; 18S rRNA assay ID: Hs99999901) using Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA levels determined by Northern blotting or TaqMan gene expression assays were normalized to 18S rRNA levels to correct for loading differences.

ELISA.

IL-8 levels in cell medium were determined by ELISA (R & D Systems).

Transcription run-on assay in isolated nuclei.

Methods for the isolation of nuclei, transcription run-on assay, and RNA isolation were according to previously described protocols (7, 19). Briefly, cells were lysed by incubation in sucrose buffer I [0.32 M sucrose, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.0, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5% (vol/vol) NP-40] for 5 min, and nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min. Nuclei were washed once in sucrose buffer I and stored in glycerol storage buffer [glycerol (40% vol/vol), 50 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.3, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM EDTA] at −80°C. For transcription run-on assay, equal numbers of nuclei were incubated in reaction buffer (5 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, and ATP, CTP, and GTP at 1 mM each) and 100 μCi of [32P]-UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol) for 30 min at 30°C. Total RNA was isolated using TRI-Reagent, and equal amounts of radioactive RNAs were hybridized to nitrocellulose membranes containing immobilized plasmid DNAs. Signals were visualized by autoradiography or Phosphor imaging.

Cell transfection and reporter gene assay.

Plasmid DNAs were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Methods for transfection of IL-8 promoter plasmids into A549 and Beas2B cells and luciferase reporter assay were according to the manufacturer's instructions. For transfection of THP-1 cells, cells (2 × 106 cells in 0.8 ml) were placed in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium without antibiotics/antimycotics for 24 h before DNA transfection. Liposome-DNA complexes were formed by incubating 2 μg of plasmid DNA with 5 μl of Lipofectamine in a total volume of 0.2 ml RPMI 1640 medium for 20 min. Afterward, Lipofectamine-DNA mixture was added to cells, and incubation continued for 5 h. After incubation, fetal bovine serum concentration and antibiotic/antimycotic concentrations in cell medium were adjusted to levels in complete medium, and incubation continued overnight (16 h). Cells were then exposed to dust extract. Luciferase activities of cell lysates were normalized to protein content. Original IL-8 promoter plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Naofumi Mukaida, Kanazawa University, Japan. Constructions of IL-8 promoter plasmids containing mutated AP-1 and NF-κB sites have been described previously (6).

Preparation of nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Methods for preparation of nuclear extracts (51) and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (4) were as described previously. DNA-protein complexes were visualized by autoradiography or Phosphor imaging. Sense-strand sequences of oligonucleotide probes used in EMSA are as follows: IL-8 AP-1: 5′-AGTGTGATGACTCAGGTTTG-3′ (−133/−114 bp); IL-8 NF-κB: 5′-AATCGTGGAATTTCCTCTGA-3′ (−84/−65 bp).

Western immunoblotting.

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% Bis-Tris gels using MOPS running buffer and electroblotted on to PVDF membranes. Membranes were first reacted with polyclonal rabbit antibodies against phospho-specific ERK, p38, or JNK overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized, according to enhanced chemifluorescence detection method, by reacting membrane with substrate followed by fluorescence scanning. Membranes were reprobed with actin or tubulin antibodies to assess for equal loading and transfer of proteins.

Statistical analyses.

Data are shown as means ± SD or SE. In experiments in which levels in control or untreated cells were arbitrarily set as 100, statistical significance was evaluated by one-sample t-test. In others, paired t-test was used to analyze statistical significance. One-tailed P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Dust extract induces IL-8 levels in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

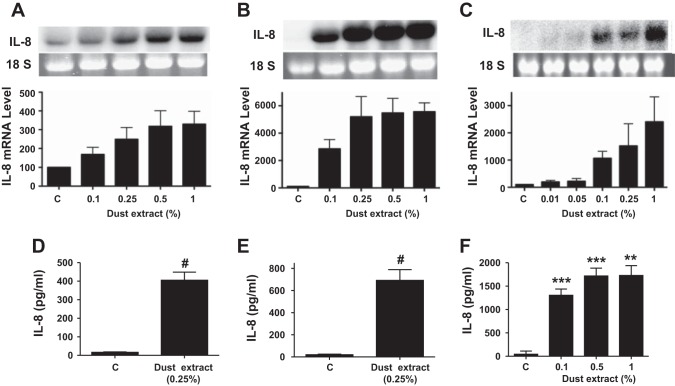

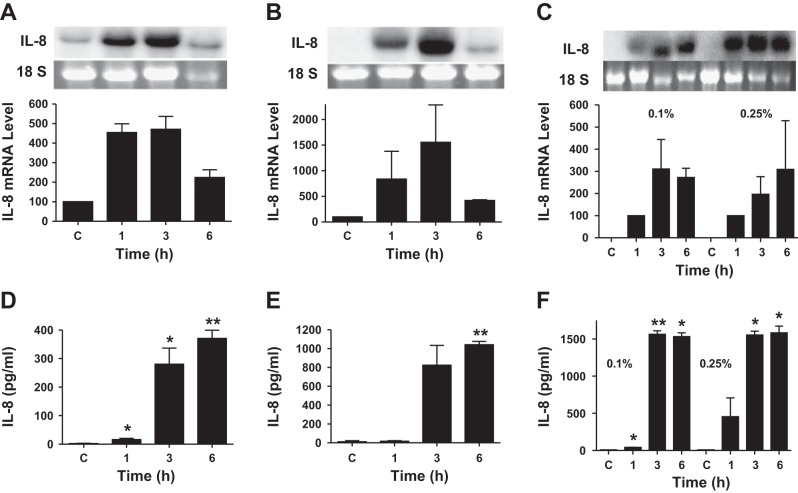

Exposure to organic dusts causes upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation (47). Poultry confinement buildings contain respirable dust levels associated with significant pulmonary function declines (15, 23). Because organic dust causes both airway and alveolar inflammation, we determined the effects of dust extract on IL-8 mRNA and protein levels in A549 and Beas2B lung epithelial cells and THP-1 monocytic cells. Dust extract increased IL-8 mRNA levels in a dose- and time-dependent manner in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells (Figs. 1 and 2). As little as 0.1% dust extract and as short as 1 h of incubation increased IL-8 mRNA levels in all the cell lines significantly. In THP-1 cells, as low as 0.01% dust extract increased IL-8 mRNA levels. Increases in IL-8 mRNA levels were associated with similar increases in IL-8 protein levels in medium; however, there was a time delay in the accumulation of IL-8 protein levels in A549 and Beas2B cell media. Similar to A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells, exposure of human primary small airway epithelial cells to dust extract increased IL-8 and IL-6 mRNA levels (data not shown). We determined the effects of dust extract on the viability of cells to ascertain that induction of IL-8 levels is not caused by cell death (data not shown). No negative effects on cell death were observed with dust extract concentrations up to 0.25% and incubation times up to 3 h in A549 and Beas2B cells and 1 h in THP-1 cells. However, higher dust extract concentration (1%) and longer incubation time (6 h) reduced cell viability by 25–40%. Therefore, in all subsequent experiments, we used dust extract at 0.25% and an incubation time of 1 h for THP-1 cells and 3 h for A549 and Beas2B cells.

Fig. 1.

Effects of dust extract on IL-8 mRNA and protein levels: dose response. A549 and Beas2B cells were treated with medium (C) or dust extract for 3 h, and THP-1 cells were treated for 1 h. IL-8 mRNA and IL-8 protein levels in culture medium were analyzed by Northern blotting and ELISA, respectively. A and D: A549 cells. B and E, Beas2B cells. C and F, THP-1 cells. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 2) for IL-8 mRNA levels and means ± SE (n = 11 for A549 cells; n = 13 for Beas2B cells; n = 3 for THP-1 cells) for IL-8 protein levels in medium. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.0001 compared with cells treated with medium alone.

Fig. 2.

Effects of dust extract on IL-8 mRNA and protein levels: time course. A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells were treated with medium (C) or dust extract (0.1% or 0.25%) for 1, 3, and 6 h. IL-8 mRNA and IL-8 protein levels in culture medium were analyzed by Northern blotting and ELISA, respectively. A and D: A549 cells. B and E: Beas2B cells. C and F, THP-1 cells. Data shown are means ± SD (n = 2) for IL-8 mRNA levels and means ± SE (n = 3 for A549 cells) and means ± SD (n = 2 for Beas2B and THP-1 cells) for IL-8 protein levels in medium. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with cells treated with medium alone.

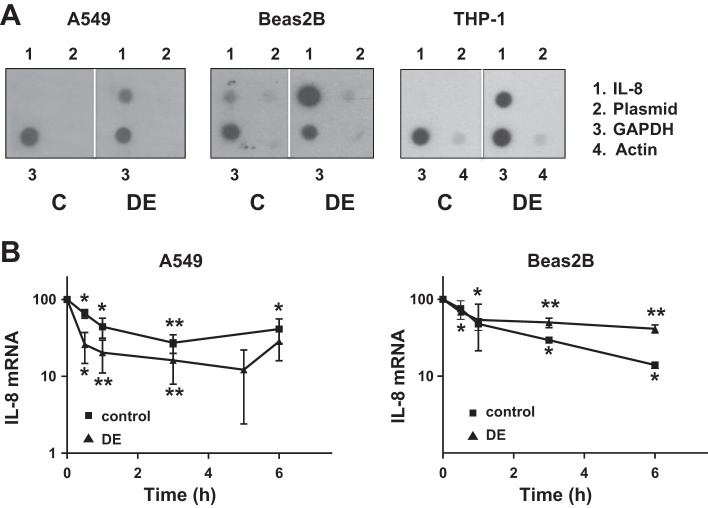

Dust extract increases IL-8 gene transcription and promoter activity.

We studied the effects of dust extract on IL-8 gene transcription rate by run-on transcription assay and on IL-8 promoter activity by transient transfection to determine whether transcriptional mechanisms mediate induction of IL-8 mRNA levels. IL-8 gene transcription was very low or undetectable in untreated A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells, but treatment with dust extract for 1 h markedly stimulated IL-8 gene transcription (Fig. 3A). Transcription of actin and GADPH were unaffected by treatment with dust extract. In agreement with these data, transient transfection analysis of IL-8 promoter plasmid showed that dust extract stimulated IL-8 promoter activity in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells (Fig. 5), indicating that transcriptional mechanisms are important for increase of IL-8 levels.

Fig. 3.

Effects of dust extract on IL-8 gene transcription and IL-8 mRNA stability. A: A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells were treated with medium (C) or dust extract (0.25%) (DE) for 1 h, and IL-8, GAPDH, and actin gene transcription rates were determined by nuclear run-on assay using isolated nuclei. Similar results were obtained in a 2nd independent experiment. B: cells were treated with medium or dust extract (0.25%) for 3 h to induce IL-8 mRNA levels and then exposed to actinomycin D (5 μM) to inhibit new RNA synthesis. IL-8 mRNA levels, following exposure to actinomycin D, were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Data shown are means ± SD or SE (n = 3 for A549 cells and n = 2 for Beas2B cells). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with cells treated with medium alone.

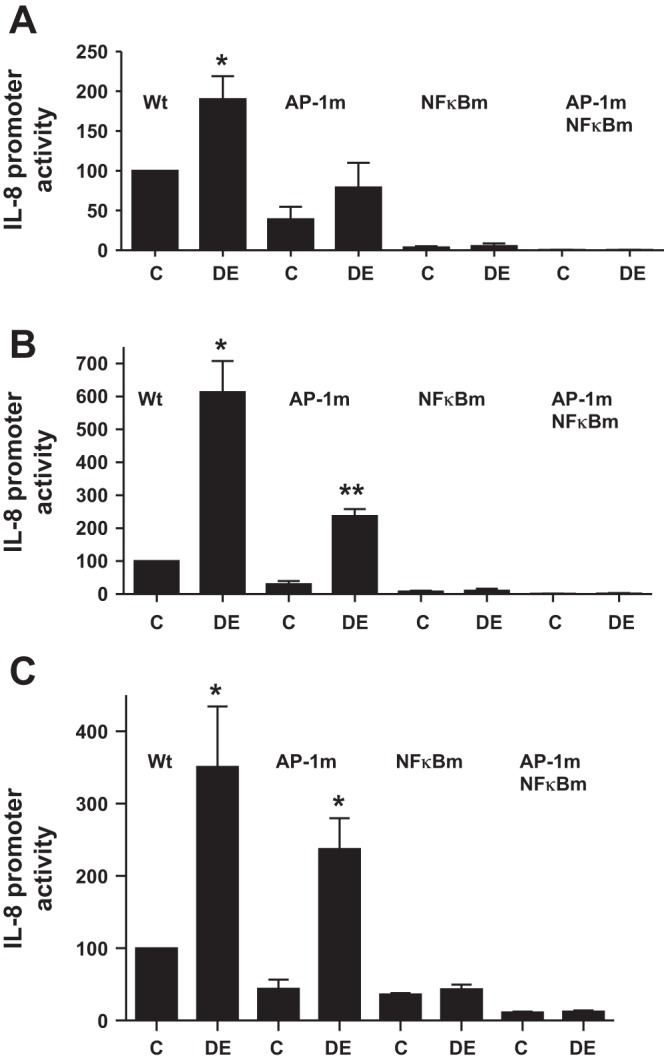

Fig. 5.

Effects of AP-1 and NF-κB mutations on IL-8 promoter activity. A549 (A), Beas2B (B), and THP-1 (C) cells were transiently transfected with wild-type (Wt), AP-1 (AP-1m), NF-κB (NFκBm), or AP-1 and NF-κB double-mutant human IL-8 promoter plasmids (−546/+44 bp) containing luciferase reporter gene and then treated with medium (C) or dust extract (0.25%) (DE) for 6 h. Luciferase activities were measured and normalized to total cell protein. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with cells treated with medium alone.

Effect of dust extract on IL-8 mRNA stability.

We determined the effect of dust extract on IL-8 mRNA stability in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells, as control of mRNA stability is known to modulate IL-8 mRNA levels (60). We determined IL-8 mRNA degradation in control and dust extract-treated cells after inhibition of new RNA synthesis with actinomycin D. Treatment with dust extract did not appreciably alter IL-8 mRNA half-life in A549 cells (control cells = < 1 h; dust extract-treated cells = ∼30 min) or Beas2B cells (control and dust extract-treated cells = ∼1 h) (Fig. 3B). The half-life of IL-8 mRNA in untreated THP-1 cells could not be determined with certainty, as its levels were very low or undetectable; however, the half-life of IL-8 mRNA in dust extract-treated cells (∼30 min) was similar to half-life in A549 and Beas2B cells (data not shown).

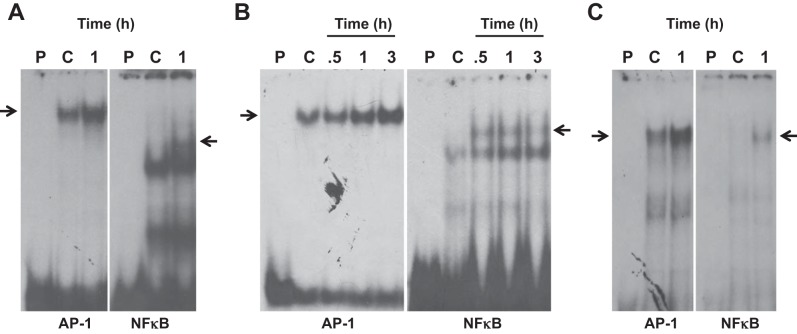

Dust extract induces AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activities.

Transcription run-on and transient transfection assays indicated that transcriptional mechanisms primarily mediate dust extract induction of IL-8 mRNA in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells. We determined the effects of dust extract on AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activities to understand their role in the stimulation of IL-8 transcription. Dust extract increased AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activities in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells, suggesting that they may be important for increased IL-8 transcription (Fig. 4, A–C). In EMSA experiments, we found that 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled IL-8 promoter AP-1 and NF-κB oligonucleotides, but not mutant ones, prevented formation of DNA-protein complexes (data not shown), indicating that IL-8 AP-1 and NF-κB sites interact with bona fide AP-1 and NF-κB proteins. Furthermore, transient transfection experiments in THP-1 cells showed that dust extract (0.25%) increased NF-κB reporter [pTranslucent NF-κB (1), Panomics] expression (control = 100, dust extract = 2,583 ± 400, mean ± SE, n = 4), indicating interaction of NF-κB-binding sequence with NF-κB proteins. We determined the importance of AP-1 and NF-κB DNA elements by analyzing the effects of mutations on induction of IL-8 promoter activity (Fig. 5). Mutations of AP-1, NF-κB, or both decreased basal and dust extract induction of IL-8 promoter activity. Mutation of NF-κB DNA element alone had a more pronounced inhibitory effect on basal and induced IL-8 promoter activity than AP-1 mutation. Combined mutations of AP-1 and NF-κB drastically decreased IL-8 promoter activity and nearly completely abolished dust extract induction of IL-8 promoter activity. These data indicated that dust extract stimulates IL-8 transcription via increased binding of AP-1 and NF-κB to IL-8 promoter.

Fig. 4.

Effects of dust extract on IL-8 activator protein 1 (AP-1) and NF-κB DNA-binding activities. A549 (A), Beas2B (B), and THP-1 (C) cells were treated with medium (C) or dust extract (0.25%) for 0.5–3.0 h, and AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activities were determined by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Results of representative experiments are shown. Similar results were obtained in 3 other independent experiments. Arrows indicate AP-1 or NF-κB DNA-protein complexes. P, probe only.

Protein kinase signaling mediates IL-8 induction.

Protein kinases modulate intracellular signaling to control gene expression, inflammatory responses, cell growth and differentiation, and other cellular processes (14, 24). We determined whether protein kinase signaling mechanisms are important for induction of IL-8 expression by dust extract. Exposure of A549, Beas2B, or THP-1 cells rapidly increased protein kinase C phosphorylation, detected with an antibody that recognizes phosphorylation of several PKC isoforms, indicating its activation (Fig. 6, A–C). PKC inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide I, Go6983, and Go6976 inhibited IL-8 mRNA and protein levels by varying degrees in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells, indicating the importance of PKC signaling in the induction (Fig. 7, A–C). Whereas bisindolylmaleimide significantly inhibited IL-8 induction in all cells, Go6983 was more effective than Go6976 in A549 and Beas2B cells, whereas Go6976 was more effective than Go6983 in THP-1 cells. Because MAPKs couple various cell surface stimuli to cellular responses and are controlled by PKC (11), we determined whether MAPK activation is necessary for IL-8 induction by dust extract. Treatment with dust extract activated ERK, p38, and JNK MAP kinases in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6, D–F). Similar to PKC inhibitors, MAPK inhibitors differentially inhibited IL-8 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 7, A–C). ERK MAPK inhibitor PD98059 significantly (∼50%) reduced dust extract induction of IL-8 mRNA and protein levels in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells. Protein kinase inhibitors by themselves did not affect IL-8 mRNA levels, and dimethylsulfoxide, which served as a carrier for the inhibitors, by itself did not alter IL-8 mRNA levels induced by dust extract (data not shown). Treatment with protein kinase inhibitors did not cause noticeable changes in cell shape or cell attachment and 18S rRNA levels, indicating lack of toxicity (data not shown). Interesting differences in the sensitivities of A549 and Beas2B cells toward p38 and JNK MAPK inhibitors were found. Whereas p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 had no effect on IL-8 levels in A549 cells, it reduced IL-8 levels in Beas2B cells, and JNK MAPK inhibitor SP60012 modestly inhibited IL-8 levels in A549 cells but failed to inhibit in Beas2B cells. ERK, p38, and JNK MAPK inhibitors equally abrogated IL-8 induction in THP-1 cells. PKC and MAPK inhibitors reduced IL-8 mRNA and IL-8 secretion by a similar extent, indicating that the activations of PKC and MAPK are necessary for increase of IL-8 transcription. Consistent with the data of chemical inhibitors, siRNA knockdown of ERK MAPK significantly reduced IL-8 induction in A549 and Beas2B cells (data not shown). Separately, we determined the specificity of MAPK inhibitors by investigating their effects on phorbol myristate acetate (10 nM) activation of MAPKs and found that they specifically inhibited their target enzymes, except that ERK inhibitor PD98059 also blocked JNK activation (data not shown). This is not surprising, as PD98059 is known to inhibit JNK activation (49).

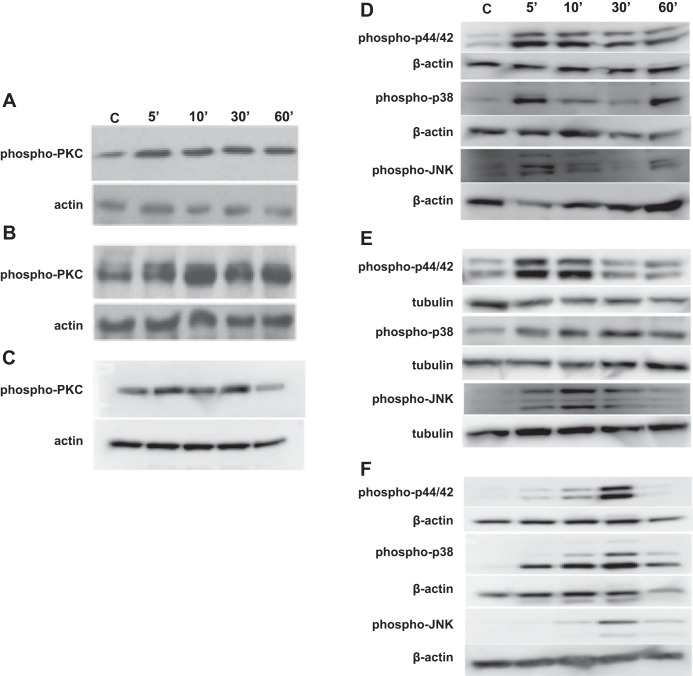

Fig. 6.

Effect of dust extract on phosphorylation of protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). Cells were treated with medium (C) or dust extract (0.25%) for indicated times and levels of phosphorylated PKC, p44/p42, p38, and JNK MAPKs were analyzed by Western blotting. The phospho-PKC (pan) antibody detects several isoforms of phosphorylated PKC. Same blots were probed for actin or tubulin, which served as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Similar results were obtained in 2 other independent experiments. A and D: A549. B and E: Beas2B. C and F: THP-1.

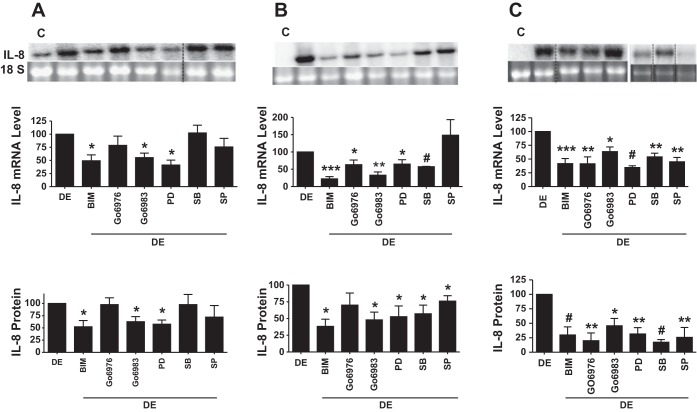

Fig. 7.

Effects of protein kinase inhibitors on dust extract induction of IL-8 mRNA and protein levels. Cells were first treated with inhibitors for 1 h and then exposed to dust extract (0.25%) (DE) in the presence of inhibitors for 3 h (A549 and Beas2B) or 1 h (THP-1). IL-8 mRNA and IL-8 protein levels in medium were analyzed by Northern blotting and ELISA. Data are means ± SE (n = 3–4). A: A549 cells. B: Beas2B cells. C: THP-1 cells. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; #P < 0.0001 compared with cells treated with DE alone. Noncontiguous lanes were reassembled and are demarcated by dashed black lines. C, medium; BIM, bisindolylmaleimide I; PD, PD98059; SB, SB203580; SP, SP60012.

Effect of polymyxin B on IL-8 induction.

Poultry dust contains a number of organic and inorganic substances that are potential inducers of IL-8 expression. Our preliminary studies on the fractionation of poultry dust extract indicated that almost all of IL-8-inducing activity was contained in >10-kDa fractions, indicating that low-molecular-weight substances in dust extract may not be important for IL-8 induction (unpublished observations, R. Saito and V. Boggaram). LPS, peptidoglycan, and ergosterol are some of the major bioactive agents in dust that are potential inducers of IL-8 expression. We found that poultry dust extracts contained high levels of endotoxin (621 ± 116 EU/mg, mean ± SE, n = 3), trace amounts of muramic acid (4.66 ± 0.208 ng/mg, mean ± SE, n = 3), a marker of peptidoglycan, and undetectable levels of ergosterol. To determine whether or not endotoxin was efficiently extracted into the aqueous medium, we extracted dust samples with pyrogen-free water containing 0.05% Tween and compared levels of endotoxin, muramic acid, and ergosterol between dust samples extracted with cell culture medium or 0.05% Tween. Tween is known to efficiently extract endotoxin from a variety of dust samples (54). We found that Tween extracts contained endotoxin activity at 1,046 ± 18.9 EU/mg (mean ± SE, n = 3) and muramic acid at 117 ± 6.9 ng/mg (mean ± SE, n = 3), but ergosterol was not detectable. These data showed that cell culture medium efficiently extracted endotoxin, but not peptidoglycan, from dust samples. We determined the importance of endotoxin by analyzing the effects of polymyxin B, an inhibitor of endotoxin, on dust extract induction of IL-8 levels (Fig. 8, A–C). We found that polymyxin B (5–20 μg/ml) did not block induction of IL-8 mRNA or protein levels, indicating that LPS in dust extract may not be important for IL-8 induction. In Beas2B and THP-1 cells, polymyxin B potentiated IL-8 mRNA levels induced by dust extract (Fig. 8, B and C). In separate experiments, we tested the effectiveness of polymyxin B by determining its effect on LPS induction of IL-8 in THP-1 cells and found that polymyxin B (5 and 10 μg/ml) inhibited IL-8 mRNA levels by >80% (data not shown).

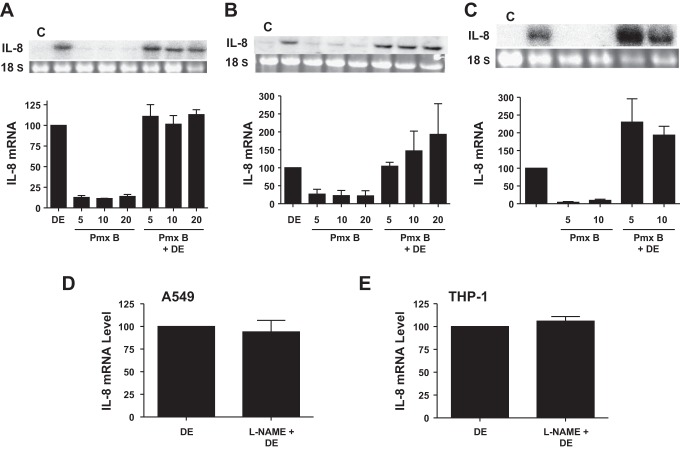

Fig. 8.

Effect of polymyxin B or nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-nitroarginine methyl ester (l-NAME) on dust extract induction of IL-8 mRNA levels. Cells were treated with medium (C), dust extract (DE) (0.25%), polymyxin B (Pmx B) (5–20 μg/ml), or a combination of Pmx B and DE for 3 h (A549 and Beas2B) or 1 h (THP-1). Cells were treated with medium or l-NAME (1 mM) for 1 h and then exposed to DE (0.25%) for 3 h (A549) or 1 h (THP-1). IL-8 mRNA levels were analyzed by Northern blotting or real-time qRT-PCR. Data are means ± SD (n = 2) or means ± SE (n = 3–5). A: A549 cells (n = 2). B: Beas2B cells (n = 3). C: THP-1 cells (n = 4). D: A549 cells (n = 2). E: THP-1 cells (n = 2).

Effect of NO synthase inhibitor on induction of IL-8 levels.

NO is a well-known proinflammatory agent (39) and a positive regulator of IL-8 levels (55). We tested whether elevated production of NO in cells exposed to dust extract mediates increase of IL-8 levels. NO is produced by the actions of constitutive and inducible NO synthases. Bacterial products, such as LPS, and cytokines stimulate the levels of inducible NO synthase to produce elevated levels of NO. We determined the effects of l-nitroarginine methyl ester (l-NAME), an inhibitor of all forms of NO synthases, on dust extract induction of IL-8 mRNA levels. We found that inhibition of NO synthases in A549 and THP-1 cells had no effect on IL-8 mRNA induction by dust extract (Fig. 8, D and E), indicating that NO does not mediate IL-8 induction.

DISCUSSION

It is a well-known fact that exposure to agricultural dusts causes respiratory symptoms and respiratory diseases (22, 58), but information on the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms is inadequate. Because inflammation plays a key role in the development of cell/tissue injury, understanding mechanisms mediating inflammatory responses is important for the development of new treatments. Gene expression analysis by DNA microarray indicated upregulation of various cytokine mRNAs in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells exposed to poultry dust extract (V. Boggaram, unpublished observations). In this study, we report on the molecular mechanisms mediating induction of IL-8, a prototypic inflammatory cytokine/chemokine (37), by poultry dust extract in lung epithelial and THP-1 monocytic cells. We studied the effects of poultry dust, as very little is known about cellular and molecular mechanisms of lung inflammatory responses to poultry dust. Additionally, the poultry industry is rapidly expanding worldwide and could have significant impact on the respiratory health of workers (1, 2). We show that aqueous extract of poultry dust is a potent inducer of IL-8 mRNA and protein levels in A549 and Beas2B lung epithelial cells and THP-1 monocytic cells. Dust extract induction of IL-8 was primarily due to an increase in IL-8 gene transcription, and the stability of IL-8 mRNA was not affected. DNA binding and mutational studies showed that AP-1 and NF-κB binding is necessary to increase IL-8 promoter activity, with NF-κB playing a greater role than AP-1 in the induction. Because AP-1 and NF-κB are key players in inflammatory responses (30, 52), their induction by poultry dust could represent a common mechanism for increased production of cytokines and other inflammatory proteins in the lung. Previous studies reported that aqueous extracts of swine barn dust (40, 46), school dust (3), and cattle feed lot dust (61) increased IL-6 and IL-8 levels in A549 and Beas2B lung cells, and swine dust extract increased IL-6 promoter activity via NF-κB activation (31). By determining the effects of poultry dust extract on IL-8 gene transcription rate and IL-8 mRNA stability and the effects of AP-1 and NF-κB mutations on IL-8 promoter, we have provided direct evidence for transcriptional mechanisms acting via binding of AP-1 and NF-κB for increased production and secretion of IL-8.

We found that IL-8 induction in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells was associated with PKC and MAPK activation. Inhibition of IL-8 mRNA and protein levels by broad-spectrum PKC inhibitors such as bisindolylmaleimide I and Go6983 in A549, Beas2B, and THP-1 cells and by the more selective PKC inhibitor Go6976 in THP-1 cells further support the importance of PKC activation for IL-8 induction. Whereas the p44/42 MAPK inhibitor PD98059 significantly inhibited IL-8 levels in A549 and Beas2B cells, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 and JNK MAPK inhibitor SP60012 were less effective. In THP-1 cells, PD98059, SB203580, and SP60012 were equally effective to inhibit IL-8 mRNA and protein levels. These data indicate that, whereas PKC activation is necessary for induction of IL-8, the roles of individual MAPKs differ depending on the cell type. Further studies are required to identify PKC enzymes required for IL-8 induction in each of these cell types. Swine barn dust extract (44, 46) and cattle feedlot dust extract (62) induce IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in bronchial epithelial cells via PKC activation. It is known that PKC serves as an upstream activator of MAP kinases. A549 (34), Beas2B (50), and THP-1 (18) cells express Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and the signaling pathways activated by poultry dust extract, namely PKC, MAPKs, AP-1, and NF-κB, are similar to those mediated via activation of TLR4 signaling pathway (32, 33).

MAPKs control IL-8 expression via transcriptional and mRNA stabilization mechanisms (21, 60). MAPKs differentially regulate IL-8 expression depending on the cell type and the stimulus. In human airway epithelial cells, although cadmium activated ERK, p38, and JNK MAPKs, only inhibition of ERK MAPK suppressed IL-8 secretion (12). In U937 cells, Helicobacter pylori VacA protein induces IL-8 expression primarily via activation of p38 MAPK even though ERK MAPK is also activated (20). In H441 lung epithelial cells, although Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 protein activates ERK, p38, and JNK MAPKs, IL-8 induction is sensitive to inhibition of ERK and p38 MAPKs, but not JNK MAPK (6).

Cellular responses to aqueous poultry dust extract as found in our study may differ from responses to dust particles per se because aqueous extracts lack lipid-soluble components and particulate matter. Nevertheless, our data showed that aqueous poultry dust extract potently induced IL-8 expression and activated protein kinase signaling pathways, indicative of proinflammatory responses. In preliminary experiments in A549 cells, we found that poultry dust extract was as potent as dust particles, on an equal weight basis, in inducing IL-8 mRNA levels (data not shown). Poultry dust extracts contained high levels of endotoxin activity but low levels of muramic acid, a marker for peptidoglycan, and ergosterol could not be detected. Lack of ergosterol and low levels of peptidoglycan could be due to the extraction of dust without detergent (e.g., Tween). Detergent was not included in the extraction medium, as it would damage cells, resulting in data that are difficult to interpret. Blocking endotoxin with polymyxin B did not inhibit the ability of dust extract to induce IL-8 levels, suggesting that endotoxin in the dust extract may not act independently to induce IL-8 levels. In a preliminary experiment in A549 cells, Escherichia coli LPS (2 μg/ml, total 4 μg, 2,000 EU) induced IL-8 mRNA less than twofold, whereas poultry dust extract (0.25%, 302 EU) induced IL-8 mRNA by greater than sixfold in agreement with the lack of effects of LPS on IL-8 mRNA levels. Our findings are similar to previous studies that found that neutralization of endotoxin in swine barn dust extract with polymyxin B did not suppress PKC activation or IL-6 and IL-8 release in bronchial epithelial cells (46). Other evidence, such as the lack of correlation between neutrophil chemotactic activities of medium from bronchial epithelial cells exposed to grain dust extracts and endotoxin levels in extracts (59), also points to lack of direct effects of endotoxin in agricultural dusts to elicit inflammatory responses. In agreement with these findings, lung inflammatory responses in human subjects exposed to the swine-confinement environment could not be attributed solely to endotoxin levels in the environment (13). Alternatively, lack of effect of polymyxin B could be due to its inability to inhibit endotoxins in dust extracts. Because agricultural dusts contain various strains of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (38), endotoxins in agricultural dust are expected to be heterogeneous in nature. It is known that endotoxins display different sensitivities to polymyxin B inhibition depending on their origin (8). For example, whereas polymyxin B completely inhibited IL-1 induction in human monocytes by LPS from Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, it had no effect on IL-1 induction by LPS from Neisseria gonorrheae, Neisseria meningitides, Bordetella pertussis, and Salmonella enteritidis (8). Paradoxically, polymyxin B at a concentration of 10 μg/ml synergized LPS induction of IL-1 secretion in human monocytes (8). Low levels of peptidoglycan in dust extracts used in our study, coupled with previous observations that peptidoglycan was a weak stimulator of IL-6 and IL-8 levels in bronchial epithelial cells (46), suggest that peptidoglycan in dust extracts used in our study may not contribute significantly to IL-8 induction. Elevated NO and IL-8 levels are associated with lung inflammation. Treatment of A549 and THP-1 cells with poultry dust extract in the presence of NO synthase inhibitor l-NAME had no effect on IL-8 induction, indicating that NO does not mediate IL-8 induction.

In conclusion, we found that poultry dust extract is a potent stimulator of IL-8 synthesis and secretion in lung epithelial and THP-1 monocytic cells. Although endotoxin was present in dust extracts, it did not seem to be important for induction of IL-8 expression. IL-8 induction was primarily due to an increase in IL-8 gene transcription mediated via increased AP-1 and NF-κB binding to IL-8 promoter. IL-8 induction was associated with activation of PKC and MAPK and sensitive to PKC and MAPK inhibition, indicating signaling pathways involving PKC, MAPK, AP-1, and NF-κB for IL-8 induction. Although lung epithelial and THP-1 monocytic cells shared similar mechanisms for IL-8 induction, there were differences in the requirement for MAPKs. IL-8 induction was not dependent on endotoxin in dust extracts or mediated via NO. Activations of PKC and MAPK signaling pathways and AP-1 and NF-κB DNA-binding activities as seen in this study could have wider implications for control of lung inflammatory responses attributable to exposure to agricultural or organic dust.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Grant U54 OH007541 from the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.R.G., S.K.B., G.P.D., and V.B. performed experiments; K.R.G., S.K.B., M.W.N., G.P.D., S.J.R., and V.B. analyzed data; K.R.G., S.K.B., and V.B. interpreted results of experiments; K.R.G., S.K.B., and V.B. prepared figures; S.K.B., M.W.N., J.L.L., G.P.D., S.J.R., and V.B. edited and revised manuscript; M.W.N., J.L.L., and V.B. conception and design of research; V.B. drafted manuscript; V.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poultry and Eggs, edited by Unites States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Washington, DC: USDA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poultry Workers, edited by National Center for Farmworker Health Buda, TX: NCFH, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allermann L, Poulsen OM. Interleukin-8 secretion from monocytic cell lines for evaluation of the inflammatory potential of organic dust. Environ Res 88: 188–198, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berhane K, Boggaram V. Identification of a novel DNA regulatory element in the rabbit surfactant protein B (SP-B) promoter that is a target for ATF/CREB and AP-1 transcription factors. Gene 268: 141–151, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boggaram V. Regulation of lung surfactant protein gene expression. Front Biosci 8: d751–d764, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boggaram V, Gottipati KR, Wang X, Samten B. Early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa (ESAT-6) protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-8 (IL-8) expression in lung epithelial cells via protein kinase signaling and reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 288: 25500–25511, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boggaram V, Margana RK. Developmental and hormonal regulation of surfactant protein C (SP-C) gene expression in fetal lung. Role of transcription and mRNA stability. J Biol Chem 269: 27767–27772, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavaillon JM and Haeffner-Cavaillon N. Polymyxin-B inhibition of LPS-induced interleukin-1 secretion by human monocytes is dependent upon the LPS origin. Mol Immunol 23: 965–969, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charavaryamath C, Janardhan KS, Townsend HG, Willson P, Singh B. Multiple exposures to swine barn air induce lung inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness. Respir Res 6: 50, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark S, Rylander R, Larsson L. Airborne bacteria, endotoxin and fungi in dust in poultry and swine confinement buildings. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 44: 537–541, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem 270: 14843–14846, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cormet-Boyaka E, Jolivette K, Bonnegarde-Bernard A, Rennolds J, Hassan F, Mehta P, Tridandapani S, Webster-Marketon J, Boyaka PN. An NF-kappaB-independent and Erk1/2-dependent mechanism controls CXCL8/IL-8 responses of airway epithelial cells to cadmium. Toxicol Sci 125: 418–429, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cormier Y, Duchaine C, Israel-Assayag E, Bedard G, Laviolette M, Dosman J. Effects of repeated swine building exposures on normal naive subjects. Eur Respir J 10: 1516–1522, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dempsey EC, Newton AC, Mochly-Rosen D, Fields AP, Reyland ME, Insel PA, Messing RO. Protein kinase C isozymes and the regulation of diverse cell responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L429–L438, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donham KJ, Cumro D, Reynolds SJ, Merchant JA. Dose-response relationships between occupational aerosol exposures and cross-shift declines of lung function in poultry workers: recommendations for exposure limits. J Occup Environ Med 42: 260–269, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donham KJ, Leininger JR. Animal studies of potential chronic lung disease of workers in swine confinement buildings. Am J Vet Res 45: 926–931, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eduard W, Pearce N, Douwes J. Chronic bronchitis, COPD, and lung function in farmers: the role of biological agents. Chest 136: 716–725, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster N, Lea SR, Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. Pivotal advance: Vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibits up-regulation of human monocyte TLR2 and TLR4 by LPS and differentiation of monocytes to macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 81: 893–903, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg ME. Identification of newly transcribed RNA. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 1: 4101–41011, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hisatsune J, Nakayama M, Isomoto H, Kurazono H, Mukaida N, Mukhopadhyay AK, Azuma T, Yamaoka Y, Sap J, Yamasaki E, Yahiro K, Moss J, Hirayama T. Molecular characterization of Helicobacter pylori VacA induction of IL-8 in U937 cells reveals a prominent role for p38MAPK in activating transcription factor-2, cAMP response element binding protein, and NF-kappaB activation. J Immunol 180: 5017–5027, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann E, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Holtmann H, Kracht M. Multiple control of interleukin-8 gene expression. J Leukoc Biol 72: 847–855, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iversen M, Kirychuk S, Drost H, Jacobson L. Human health effects of dust exposure in animal confinement buildings. J Agric Saf Health 6: 283–288, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones W, Morring K, Olenchock SA, Williams T, Hickey J. Environmental study of poultry confinement buildings. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 45: 760–766, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim EK, Choi EJ. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 396–405, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirychuk SP, Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA, Juorio V, Feddes JJ, Willson P, Classen H, Reynolds SJ, Guenter W, Hurst TS. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in poultry confinement workers in Western Canada. Can Respir J 10: 375–380, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson BM, Larsson K, Malmberg P, Martensson L, Palmberg L. Airway responses in naive subjects to exposure in poultry houses: comparison between cage rearing system and alternative rearing system for laying hens. Am J Ind Med 35: 142–149, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson BM, Palmberg L, Malmberg PO, Larsson K. Effect of exposure to swine dust on levels of IL-8 in airway lavage fluid. Thorax 52: 638–642, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson KA, Eklund AG, Hansson LO, Isaksson BM, Malmberg PO. Swine dust causes intense airways inflammation in healthy subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150: 973–977, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenhart SW, Morris PD, Akin RE, et al. Organic dust, endotoxin, and ammonia exposures in the North Carolina poultry processing industry. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 5: 611–618, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 725–734, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liden J, Ek A, Palmberg L, Okret S, Larsson K. Organic dust activates NF-kappaB in lung epithelial cells. Respir Med 97: 882–892, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loegering DJ, Lennartz MR. Protein kinase C and toll-like receptor signaling. Enzyme Res 2011: 537821, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine 42: 145–151, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacRedmond R, Greene C, Taggart CC, McElvaney N, O'Neill S. Respiratory epithelial cells require Toll-like receptor 4 for induction of human beta-defensin 2 by lipopolysaccharide. Respir Res 6: 116, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin LD, Rochelle LG, Fischer BM, Krunkosky TM, Adler KB. Airway epithelium as an effector of inflammation: Molecular regulation of secondary mediators. Eur Respir J 10: 2139–2146, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monso E, Riu E, Radon K, Magarolas R, Danuser B, Iversen M, Morera J, Nowak D. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never-smoking animal farmers working inside confinement buildings. Am J Ind Med 46: 357–362, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukaida N. Pathophysiological roles of interleukin-8/CXCL8 in pulmonary diseases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 284: L566–L577, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nonnenmann MW, Bextine B, Dowd SE, Gilmore K, Levin JL. Culture-independent characterization of bacteria and fungi in a poultry bioaerosol using pyrosequencing: A new approach. J Occup Environ Hyg 7: 693–699, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nussler AK, Billiar TR. Inflammation, immunoregulation, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Leukoc Biol 54: 171–178, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmberg L, Larsson BM, Malmberg P, Larsson K. Induction of IL-8 production in human alveolar macrophages and human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro by swine dust. Thorax 53: 260–264, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poole JA, Dooley GP, Saito R, Burrell AM, Bailey KL, Romberger DJ, Mehaffy J, Reynolds SJ. Muramic acid, endotoxin, 3-hydroxy fatty acids, and ergosterol content explain monocyte and epithelial cell inflammatory responses to agricultural dusts. J Toxicol Environ Health A 73: 684–700, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poole JA, Romberger DJ. Immunological and inflammatory responses to organic dust in agriculture. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 12: 126–132, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Oldenburg PJ, Elliott MK, West WW, Sisson JH, Von Essen SG, Romberger DJ. Intranasal organic dust exposure-induced airway adaptation response marked by persistent lung inflammation and pathology in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L1085–L1095, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poole JA, Wyatt TA, Von Essen SG, Hervert J, Parks C, Mathisen T, Romberger DJ. Repeat organic dust exposure-induced monocyte inflammation is associated with protein kinase C activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 120: 366–373, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radon K, Weber C, Iversen M, Danuser B, Pedersen S, Nowak D. Exposure assessment and lung function in pig and poultry farmers. Occup Environ Med 58: 405–410, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romberger DJ, Bodlak V, Von Essen SG, Mathisen T, Wyatt TA. Hog barn dust extract stimulates IL-8 and IL-6 release in human bronchial epithelial cells via PKC activation. J Appl Physiol 93: 289–296, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rylander R. Lung diseases caused by organic dusts in the farm environment. Am J Ind Med 10: 221–227, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito R, Cranmer BK, Tessari JD, Larsson L, Mehaffy JM, Keefe TJ, Reynolds SJ. Recombinant factor C (rFC) assay and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis of endotoxin variability in four agricultural dusts. Ann Occup Hyg 53: 713–722, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salh BS, Martens J, Hundal RS, Yoganathan N, Charest D, Mui A, Gomez-Munoz A. PD98059 attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death through inhibition of Jun N-Terminal Kinase in HT29 cells. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 4: 158–165, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmeck B, Huber S, Moog K, Zahlten J, Hocke AC, Opitz B, Hammerschmidt S, Mitchell TJ, Kracht M, Rosseau S, Suttorp N, Hippenstiel S. Pneumococci induced TLR- and Rac1-dependent NF-κB-recruitment to the IL-8 promoter in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L730–L737, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, Schaffner W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res 17: 6419, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol 4: E131–E136, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simpson JC, Niven RM, Pickering CA, Fletcher AM, Oldham LA, Francis HM. Prevalence and predictors of work related respiratory symptoms in workers exposed to organic dusts. Occup Environ Med 55: 668–672, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spaan S, Doekes G, Heederik D, Thorne PS, Wouters IM. Effect of extraction and assay media on analysis of airborne endotoxin. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 3804–3811, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sparkman L, Boggaram V. Nitric oxide increases IL-8 gene transcription and mRNA stability to enhance IL-8 gene expression in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L764–L773, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sundblad BM, von Scheele I, Palmberg L, Olsson M, Larsson K. Repeated exposure to organic material alters inflammatory and physiological airway responses. Eur Respir J 34: 80–88, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Viegas S, Faisca VM, Dias H, Clerigo A, Carolino E, Viegas C. Occupational exposure to poultry dust and effects on the respiratory system in workers. J Toxicol Environ Health A 76: 230–239, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Von Essen S, Donham K. Illness and injury in animal confinement workers. Occup Med 14: 337–350, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Von Essen SG, O'Neill DP, Olenchok SA, Robbins RA, Rennard SI. Grain dusts and grain plant components vary in their ability to recruit neutrophils. J Toxicol Environ Health 46: 425–441, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winzen R, Kracht M, Ritter B, Wilhelm A, Chen CY, Shyu AB, Muller M, Gaestel M, Resch K, Holtmann H. The p38 MAP kinase pathway signals for cytokine-induced mRNA stabilization via MAP kinase-activated protein kinase 2 and an AU-rich region-targeted mechanism. EMBO J 18: 4969–4980, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt TA, Slager RE, Devasure J, Auvermann BW, Mulhern ML, Von Essen S, Mathisen T, Floreani AA, Romberger DJ. Feedlot dust stimulation of interleukin-6 and -8 requires protein kinase Cϵ in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1163–L1170, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wyatt TA, Slager RE, Heires AJ, Devasure JM, Vonessen SG, Poole JA, Romberger DJ. Sequential activation of protein kinase C isoforms by organic dust is mediated by tumor necrosis factor. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 42: 706–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]