Abstract

Context

It is important to identify the patients at highest risk of fractures. A recent large-scale meta-analysis identified 63 autosomal SNPs associated with bone mineral density (BMD), of which 16 were also associated with fracture risk. Based on these findings two genetic risk scores (GRS63 and GRS16) were developed.

Objective

To determine the clinical usefulness of these GRS for the prediction of BMD, BMD change and fracture risk in elderly subjects.

Design, Settings and Participants

Two male (MrOS US, MrOS Sweden) and one female (SOF) large prospective cohorts of older subjects.

Main Outcome Measures

BMD, BMD change and radiographically and/or medically confirmed incident fractures (8,067 subjects, 2,185 incident non-vertebral or vertebral fractures).

Results

GRS63 was associated with BMD (≅3% of the variation explained), but not with BMD change.

Both GRS63 and GRS16 were associated with fractures. After BMD-adjustment, the effect sizes for these associations were substantially reduced.

Similar results were found using an unweighted GRS63 and an unweighted GRS16 compared to those found using the corresponding weighted risk scores.

Only minor improvements in C-statistics (AUC) for fractures were seen when the GRSs were added to a base model (age, weight and height) and no significant improvements in C-statistics were seen when they were added to a model further adjusted for BMD. Net reclassification improvements with the addition of the GRSs to a base model were modest and substantially attenuated in BMD-adjusted models.

Conclusions and Relevance

GRS63 is associated with BMD, but not BMD change, suggesting that the genetic determinants of BMD differ from those of BMD change. When BMD is known, the clinical utility of the two GRSs for fracture prediction is limited in elderly subjects.

Keywords: General population studies, Human association studies, Fracture risk assessment, Osteoporosis, DXA

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased risk of fragility fractures (1). The major determinants of fracture risk include bone mineral density (BMD), bone quality parameters and non-skeletal parameters such as muscle strength and balance affecting the risk of falls (2).

In the clinical setting, it is important to identify the patients at highest risk of fractures, who are most likely to benefit from osteoporosis treatment. Current available tools for the prediction of fracture risk are based on individual patient models that integrate the risks associated with clinical risk factors with or without BMD (3-5).

Twin and family studies have provided compelling evidence of substantial (50-85 %) heritability for cross-sectional BMD (6, 7). Most well-powered twin and family studies demonstrate a clear heritability (40-50%) also for BMD change (8-10). Twin studies have shown a heritability estimate of ≅ 50% for hip and forearm fractures while this is lower (≅24%) for vertebral fractures (11-13). Interestingly, the heritable component of fractures is largely independent of BMD (6, 12). These studies collectively demonstrate that genetic factors are important for BMD, BMD change and fracture risk.

Well-powered genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analyses on cross-sectional BMD have successfully identified many genetic signals while GWAS meta-analyses on BMD change have not yet been reported. Furthermore, except for a recent study focusing on vertebral fractures, there are no published studies using GWAS meta-analysis on fracture risk (14). The first GWAS analysis on BMD was published in 2007 and the number of loci identified has been increasing proportional to the number of subjects included in the meta-analyses (9, 15-21). By far the largest and most recent GWAS meta-analysis on BMD, including in total more than 80,000 subjects, was recently reported by the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) consortium (15). Estrada et al. identified 63 autosomal Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with BMD and 16 of these BMD-associated SNPs were also significantly associated with prevalent fractures. Based on these genetic signals, two genetic risk scores (GRS63 and GRS16) were developed. The authors proposed that the GRS63 could be used for the prediction of BMD while the GRS16 could be used for the prediction of fracture risk. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to determine the clinical usefulness of these genetic risk scores for the prediction of BMD, BMD change and fracture risk in elderly subjects. The role of the GRS63 for the prediction of BMD change is not yet evaluated. As both GRS16 and GRS63 are derived from a BMD GWAS meta-analysis, possible associations with fracture risk are most likely largely mediated by BMD. However, BMD is not readily available for many elderly all around the world. In addition, whereas BMD values will change over time, our genes remain constant. As a result, a genetic risk score might potentially help identify subjects at risk earlier in life before a BMD measurement has been performed. It might also provide additional information besides a single BMD value, which does not capture all of the BMD information during a lifetime, for fracture risk prediction. Genotype data from two male (Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) US and MrOS Sweden) and one female (Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF)) large cohorts of older Caucasian participants were evaluated against BMD (n=8,212), BMD change (n=5,312), and incident fractures (n=8,067 including 2,185 incident fracture cases). Since BMD is the best single predictor of both non-vertebral and vertebral fractures and sometimes known, the clinical usefulness of these genetic risk scores for fracture discrimination and reclassification was evaluated in models with or without BMD.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

MrOS Sweden

The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study is a multicenter, prospective study including older men in Sweden, Hong Kong, and the United States. The Gothenburg part (n=1,010) of the Swedish MrOS cohort (n=3,014) shared genotyping platform, quality control and imputation platform with MrOS US and SOF and was included in the present study. The study subjects (men 69–80 yr of age) were randomly identified using national population registers. A total of 45% of the subjects who were contacted participated in the study. To be eligible for the study, the subjects had to be able to walk without aids. Individuals taking osteoporotic medicine (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, calcitonin, strontium ranelate, parathyroid hormone) were excluded. There were no other exclusion criteria (22). The study was approved by the ethics committee at the University of Gothenburg. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

MrOS US

The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study enrolled 5,994 participants from March 2000 through April 2002. Recruitment occurred at six US clinical centers (Birmingham, AL; Minneapolis, MN; Palo Alto, CA; Pittsburgh, PA; Portland, OR; and San Diego, CA) and was accomplished primarily through mass mailings targeted to age-eligible men. Eligible participants were community-dwelling men who were at least 65 years of age, able to walk without assistance from another person, and had not had bilateral hip replacements. Details of the MrOS study design and recruitment have been published elsewhere (23, 24) After excluding men reporting osteoporotic medication, 4,487 men who reported non-Hispanic white race, had DNA available for genotyping and had baseline DXA BMD at femoral neck were included in the analyses of baseline BMD and fracture risk. Of these, 3,168 men who had repeat BMD (at the femoral neck) at a follow-up visit were included in the analysis of bone loss. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the Institutional Review Board at each study site approved the study.

SOF

The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) is a prospective multicenter study of risk factors for vertebral and non-vertebral fractures (25). The cohort is comprised of 9,704 community dwelling women 65 years old or older recruited from populations-based listings in four U.S. areas: Baltimore, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; and the Monongahela Valley, Pennsylvania. Women enrolled in the study were 99% Caucasian with African American women initially excluded from the study due to their low incidence of hip fractures. The SOF participants were followed up every four months by postcard or telephone to ascertain the occurrence of falls, fractures and changes in address. To date, follow-up rates have exceeded 95% for vital status and fractures. All fractures are validated by x-ray reports or, in the case of most hip fractures, a review of pre-operative radiographs.

The inclusion criteria at enrollment were: 1) 65 years or older, (2) ability to walk without the assistance of another, (3) absence of bilateral hip replacements, (4) ability to provide self-reported data, and (5) ability to understand and sign an informed consent. To qualify as an enrollee, the participant had to provide written informed consent, complete the self-administered questionnaire (SAQ), attend the clinic visit, and complete at least the anthropometric measures. The SOF study recruited only women.

Assessment of covariates

MrOS Sweden and MrOS US

Height was measured using a Harpenden stadiometer, and weight was measured by a standard balance beam or an electric scale. Two consecutive measurements of height were performed in the same session, and the average of these measurements was calculated. If there was a difference of ≥5 mm between the first two measurements, a third measurement was performed, and the average of the two values with the least mutual discrepancy was calculated.

SOF

Weight was measured using a standard balance beam scale, without shoes or heavy outer clothing. Each clinical site had a 50 kg weight for calibration. Height was measured using a Harpenden stadiometer.

Genotyping and Quality Control Methods

Genotyping in all three cohorts was performed using the Illumina HumanOmni1_Quad_v1-0 B array. For further details of genotyping and quality control please see supplemental material. Two weighted genetic risk scores (GRS) were calculated as described by Estrada et al (15). One GRS was based on the 63 BMD-associated SNPs, the GRS63, while the other GRS was based on the 16 BMD-associated SNPs that were also associated with fracture risk, the GRS16 (15). The two multilocus genetic risk scores were calculated for each individual by summing the number of risk alleles (dosage) for each SNP weighted by the SNP's estimated effect size. In the first risk score based on the 63 BMD-associated SNPs, the GRS63, weights were derived from a previous meta-analysis (15), which based these on the FN-BMD-effect size of each SNP's BMD-decreasing allele and then transformed the weights to have a mean=1 by dividing each effect size by the mean of the femoral neck BMD effect sizes. The second genetic risk score, based on the 16 BMD-associated SNPs, which were also significantly associated with prevalent fractures (the GRS16), was calculated similarly, except for the weights, which were calculated based on the effect size each risk-increasing allele had on the risk of any type of fracture in the study by Estrada et al. (15). The performances of the GRS63 and GRS16 for fracture prediction were evaluated by comparing effect sizes and by including both genetic risk scores in a combined Cox proportional hazard model. In addition to the primary analyses using weighted risk scores, sensitivity analyses were performed using unweighted risk scores. These were calculated based on the number of risk alleles of the 63 and 16 SNPs, respectively, and then tested using the same linear regression (unweighted GRS63) and Cox proportional hazard models (unweighted GRS63 and unweighted GRS16) as described above for BMD and fracture risk.

Assessment of bone mineral density and change of bone mineral density

MrOS Sweden

Areal BMD (aBMD, g/cm2), later referred to as BMD, of the femoral neck (FN) and lumbar spine (L1 to L4, LS) was assessed at baseline using DXA with the Hologic QDR 4500/A-Delphi (Hologic, Waltham, MA). The coefficients of variation for the BMD measurements ranged from 0.5% to 3% depending on the application (22).

MrOS US

Similarly, BMD of the FN and LS in the US were measured using DXA with Hologic QDR-4500W scanners (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA). In the US cohort, BMD was measured at baseline and a follow-up visit a mean of 4.6 years later. Follow-up measurements were performed on the same instruments as were used for the baseline measurements. A central quality control laboratory, certification of DXA technicians, and standardized procedures for scanning were implemented to ensure reproducibility of DXA measurements. At baseline, a hip phantom was circulated and scanned at the six clinical centers. Cross-calibration studies indicated no linear differences across scanners, and the interscanner CV was 0.9%. Each clinic scanned a hip phantom throughout the study to monitor longitudinal changes, and correction factors were applied to participant data as appropriate. In addition, multivariable models included an indicator variable for the individual clinic center to adjust for interclinic differences.

SOF

During a follow-up visit, between 1989 and 1990, BMD of the proximal femur and spine was measured using DXA (QDR-1000, Hologic, Waltham, MA) (24) while change in femoral neck BMD was based on the annualized change from visit 2 (1989-1990) to visit 4 (1992-1994; resulting in an average follow-up time of 3.9 years for BMD change). Densitometry quality control methods have been published elsewhere (26, 27). In brief, paired initial and follow-up hip scans were analyzed using the automated “compare” feature of the Hologic software. Quality control center technicians reviewed a random sample. In addition, all scans identified by the technicians for certain problems such as changes in positioning between the initial and follow-up scans or difficulty defining bone edges were reviewed at the quality control center. An anthropometric spine phantom was scanned daily, and a hip phantom was scanned once per week at each clinic to assess longitudinal performance of the scanners.

Assessment of incident fractures

MrOS Sweden

Participants were followed for 5.2 years on average after the baseline examination. The follow-up time was recorded from the date of the baseline visit to the date of the first fracture or the date of death. Time of death for all subjects who died during the study was documented from the Swedish National Cause of Death Register. This register comprises records of all deaths in Sweden. At the time of fracture evaluation, the computerized X-ray archives in Gothenburg were searched for new fractures occurring after the baseline visit, using the unique personal registration number, which all Swedish citizens have. All fractures reported by the study subject after the baseline visit were confirmed by physician review of radiology reports. Fractures reported by the study subject, but not possible to confirm by X-ray analyses report, were not included in this study. We studied the associations between the genetic risk scores and validated incident fractures divided into three main groups: (1) all fractures, (2) non-vertebral osteoporosis fractures at the major osteoporosis-related locations (defined as hip, distal radius, proximal humerus and pelvis), and (3) hip fractures.

MrOS US

Participants were followed for 8.6 years on average after the baseline examination. The follow-up time was recorded from the date of the baseline visit to the date of the first fracture or the date of death. Subjects were followed for incident fracture with a triannual questionnaire administered by mail or telephone. Reports of fracture were followed up by study staff to determine date, description of how the fracture occurred, and any trauma that resulted in the fracture. Fractures were verified centrally by physician adjudication of medical records and X-ray reports (28). During follow-up, next of kin were contacted for men with unreturned questionnaires who could not be reached by telephone. Deaths were confirmed with death certificates.

SOF

The subjects completed postcard questionnaires every 4 months (triannual) between clinic visits reporting incident fractures. The clinic staff contacted subjects to confirm fracture event and collected information using a standard questionnaire on date of fracture and circumstances surrounding the fracture. Medical records were obtained and reviewed by clinic PIs and fracture validation forms were forwarded to the coordinating center for review. X-rays were requested for proximal femur fractures in order to determine severity (displaced, non-displaced) (25). Follow-up for this analysis was 12.7 years.

Statistical analyses

BMD and BMD change

The Z-scored femoral neck BMD (FN-BMD) and lumbar spine BMD (LS-BMD) values were calculated as the difference between the observed BMD measurement from the DXA machine and the corresponding population mean divided by the standard deviation of the population (MrOS Sweden, MrOS US or SOF). These Z scores were then adjusted for age, weight, site and principal components (PC), used for controlling for population stratification, in linear regression models. The analysis of imputed genotype data accounted for uncertainty in each genotype prediction by using dosage information from minimac (29). The results from individual cohorts were meta-analyzed using an inverse variance fixed-effects model.

To illustrate the associations between GRS63 and BMD and BMD change, the participants, in each cohort and combined, were divided into five bins based on their genetic risk score, using similar distribution as Estrada et al (9%, 24%, 34%, 25%, 9%) and then rounding to the nearest genetic risk score integer (15). The z-scored mean FN-BMD of each bin adjusted for age, weight, site and PC was then tested against the middle bin using a standard t-test. P for trend for the bins was also calculated.

The same tests were performed for BMD change using a z-scored annualized percentage change in FN-BMD and LS-BMD, both with and without adjustment for baseline BMD.

Fractures

In order to be able to compare the performance of the GRS63 with that of the GRS16, all effect sizes are given per SD increase in genetic risk score for the fracture analyses. Risk for fracture based on the GRS63 and the GRS16 was analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for age, weight, height, site and PC. The BMD-independent fracture risk was tested by also adjusting for baseline FN-BMD. The estimated fracture risk explained by BMD was calculated as [beta(without BMD adjustment) - beta(with BMD adjustment)] / beta(without BMD adjustment), where betas were derived from the Cox models.

Continuous, rather than threshold-based, net reclassification improvement (NRI) was used since the incidence of all fractures in the cohorts was much higher than the 10-year risk thresholds used in FRAX (3% for hip fracture and 20% for major osteoporotic fracture - clinical spine, forearm, hip and humerus fracture) (30). In order to incorporate both the direction of change in the calculated risk and the extent of change, integrated discriminative improvement (IDI) was also calculated. Both NRI and IDI were calculated according to Pencina et al (31). Furthermore, both measures are also given separately for subjects with and subjects without fractures making it possible to determine if the calculated risk is improved primarily in those with or without fractures. NRI, IDI and a C-index were used to assess the extent to which adding the genetic risk score to a) an age-, weight- and height-adjusted model and b) an age-, weight-, height- and FN-BMD-adjusted model, improved the model's prediction of hip and all fractures. The statistical significance of change in the area under the ROC curve (AUC) between models was tested with the roc.test function in R using settings according to DeLong et al (32).

Results

Descriptive data

Combined the three cohorts included as many as 8,212 participants with baseline BMD, 5,312 participants with BMD change data and 8,067 participants with incident fracture information (2,185 all fracture cases; 618 hip fracture cases; Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Table 2). Both the GRS63 and the GRS16 had similar distributions in all cohorts (Supplemental Table 3). For BMD and BMD change, it was primarily the GRS63 that was evaluated, while both the GRS63 and the GRS16 were evaluated for fracture risk.

The GRS63 was associated with BMD

The GRS63 was significantly associated with both FN-BMD (p<0.001) and LS-BMD (p<0.001) in the combined data set (Supplemental Table 4). The variation explained in the different cohorts was very similar for both traits (FN-BMD: MrOS Sweden 3.1%, MrOS US 3.2%, SOF 2.6%; LS-BMD: MrOS Sweden 3.3%, MrOS US 2.6%, SOF, 3.2%; Supplemental Table 4). Comparable effects sizes for both FN-BMD and LS-BMD were seen in both sexes (Supplemental Table 4).

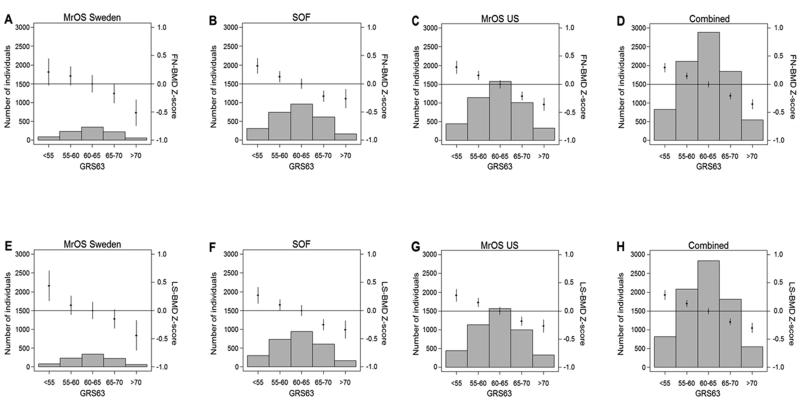

To illustrate the association between the GRS63 and BMD, all subjects were grouped into five bins according to their GRS63 as earlier described by Estrada et al (15). An increase in GRS63 bin was significantly associated with a lower FN-BMD and LS-BMD in all three cohorts and in the combined data set (Fig 1). The difference in mean BMD in the combined data set between individuals in the highest bin of the risk score (7% of the population; n=548) and those in the middle bin (35% of the population; n=2,886) was −0.36 and −0.30 SDs for FN-BMD (Fig 1D) and LSBMD (Fig 1H), respectively.

Figure 1.

The genetic risk score, GRS63, is associated with femoral neck (FN) BMD (A-D). The associations between the genetic risk score and FN-BMD are given for (A) MrOS Sweden, (B) SOF, (C) MrOS US and (D) the combined data set. Effect sizes are shown for FN-BMD standardized residuals (Z scores). The genetic risk score, GRS63, is associated with lumbar spine (LS) BMD (E-H). The associations between the genetic risk score and LS-BMD are given for (E) MrOS Sweden, (F) SOF, (G) MrOS US and (H) the combined data set. Effect sizes are shown for LS-BMD standardized residuals (Z scores). Histograms show the number of individuals in each genetic score category (left y axis). Diamonds (right y axis) represent mean adjusted FN-BMD and LS-BMD standardized levels, respectively. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. BMD was adjusted for age, weight, clinical site and population stratification. P for trend for FN-BMD: A) MrOS Sweden <0.001, B) SOF <0.001, C) MrOS US <0.001, D) Combined <0.001. P for trend for LS-BMD: E) MrOS Sweden <0.001, F) SOF <0.001, G) MrOS US <0.001, H) Combined <0.001

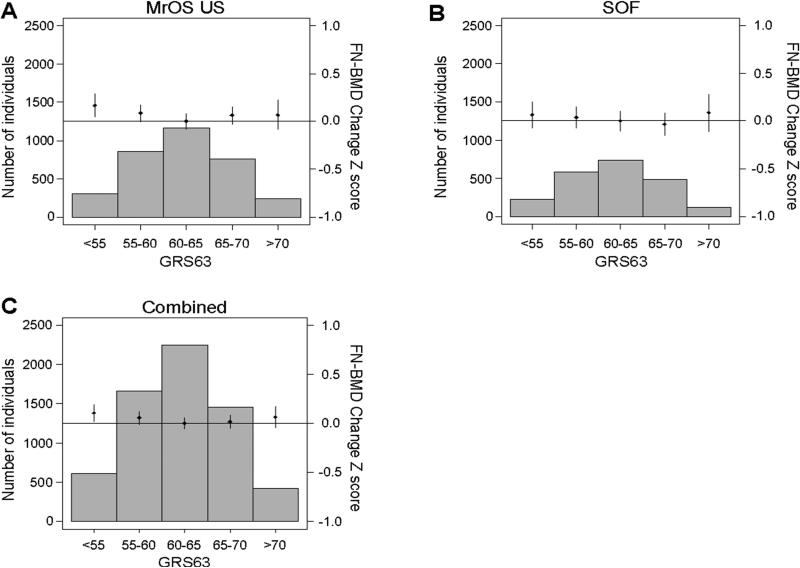

The GRS63 was not associated with BMD change

The GRS63 was not significantly associated with BMD change at any site in any of the individual cohorts or the combined data set. Similar results were seen after adjusting for baseline BMD (Fig 2, Supplemental Fig 1-2, Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 2.

The genetic risk score, GRS63, is not associated with femoral neck (FN) BMDchange. The associations between the genetic risk score in bins and FN-BMD change are given for (A) MrOS US, (B) SOF and (C) the combined data set. Effect sizes are shown for standardized yearly percent change in FN-BMD (Z scores) adjusted for age, weight, clinical site and population stratification. Histograms show the number of individuals in each genetic score category (left y axis). Diamonds (right y axis) represent mean yearly percent change in adjusted FN-BMD standardized levels. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. P for trend: MrOS US 0.190, SOF 0.394, Combined 0.132.

The GRS63 and the GRS16 were associated with fracture risk

Next, the associations of both risk scores with incident fractures were evaluated. Although both the GRS63 and the GRS16 were significantly associated with risk of all fractures in the combined data set, the effect size for the GRS63 (HR 1.16 (95% CI 1.11-1.20) per SD increase) was slightly larger than that of the GRS16 (HR 1.13 (95% CI 1.09-1.18) per SD increase). The association between GRS63 and risk of hip fracture was substantial (HR 1.20 (95% CI 1.11-1.30) per SD increase), while the corresponding association for GRS16 was less pronounced (HR 1.10 (95% CI 1.02-1.19) per SD increase; Supplemental Table 5).

The HR for all fractures was similar in men and women for the GRS63 (Supplemental Table 5). In each cohort, the GRS63 was significantly associated with risk of all fractures (HR per SD increase in GRS63, MrOS Sweden 1.31, p=0.002; MrOS US 1.16, p<0.001; SOF 1.13, p<0.001) and non-vertebral fracture risk (Supplemental Table 5, Supplemental Fig 3).

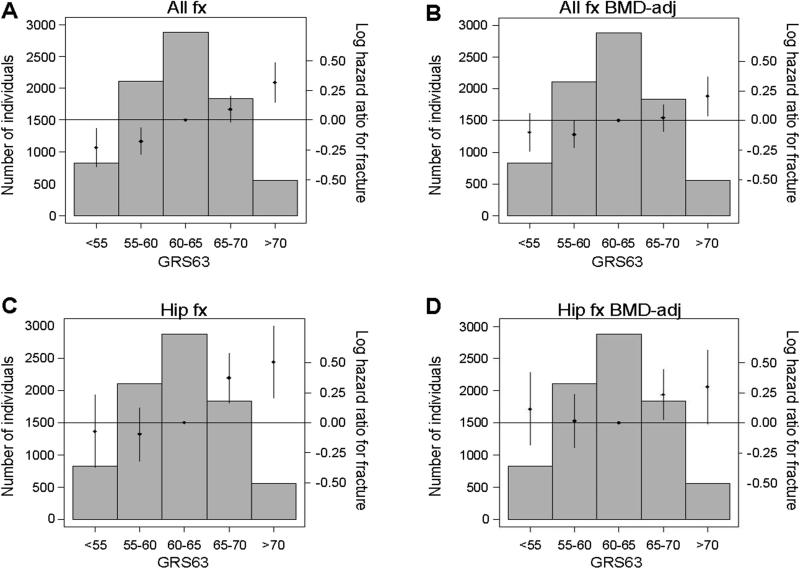

The associations of the GRS63 were also evaluated against any type of fracture and hip fracture using the bin-approach described above. Analyses of p for trend of bins demonstrated a clear association between the GRS63 and risk of both all fractures (p<0.001, Fig. 3A) and hip fractures (p<0.001, Fig. 3C) in the combined data set. Subjects in the highest bin of the GRS63 had a significantly increased risk of fracture compared to the middle bin both for all fractures (HR: 1.37 [1.16-1.62]) and hip fractures (HR=1.66 [1.23 – 2.24]) in the combined data set (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

The genetic risk score, GRS63, is associated with fracture. The association between the genetic risk score including information from 63 SNPs (GRS63) and any type of incident fracture (A, B) or hip fracture (C, D) is given for the combined data set (n=8,067 including 2,185 fracture cases). Effect sizes are given in log hazard ratios (HR). (A, C) Models are adjusted for age, weight, height, clinical site, cohort and population stratification. (B, D) Models are adjusted for age, weight, height, clinical site, cohort, population stratification and baseline femoral neck (FN) BMD. Histograms show the number of individuals in each genetic score category (left y axis). Diamonds (right y axis) represent log HR. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence limits. P for trend: (A) <0.001, (B) <0.001 (C) <0.001, (D) <0.001.

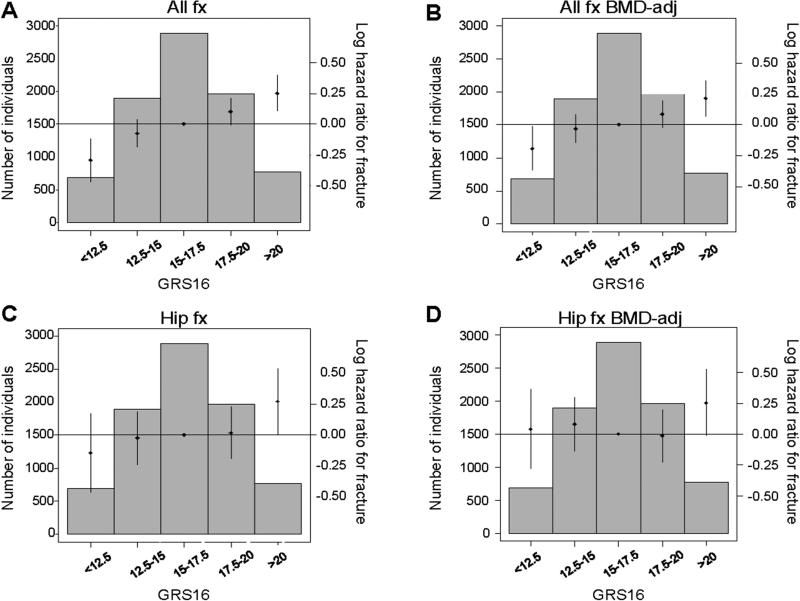

To test the BMD-independent role of the GRS63, FN-BMD-adjusted Cox models were also used. The associations between the GRS63 and both all fracture (HR per SD increase 1.07, p=0.001) and hip fracture (HR per SD increase 1.07, p=0.104) risk were substantially reduced after BMD adjustment (Supplemental Table 5, Fig 3). Evaluation of betas of the associations for GRS63 before and after BMD adjustment showed that 50% of the GRS63 effect size for all fracture and 64% of the effect size for hip fracture risk are dependent on baseline FN-BMD. The fracture associations for GRS63 and GRS16 were of similar magnitude after BMD adjustment (Supplemental Table 5, Fig 3, Fig 4).

Figure 4.

The genetic risk score, GRS16, is associated with fracture. The association between the genetic risk score including information from 16 SNPs (GRS16) and any type of incident fracture (A, B) or hip fracture (C, D) is given for the combined data set (n=8,067 including 2,185 fracture cases). Effect sizes are given in log hazard ratios (HR). (A, C) Models are adjusted for age, weight, height, clinical site, cohort and population stratification. (B, D) Models are adjusted for age, weight, height, clinical site, cohort, population stratification and baseline femoral neck (FN) BMD. Histograms show the number of individuals in each genetic score category (left y axis). Diamonds (right y axis) represent log HR. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence limits. P for trend: (A) <0.001, (B) <0.001 (C) 0.050, (D) 0.563.

Discrimination and Reclassification

Only minor improvements in C-statistics (AUC) for all fractures were seen when the GRS63 was added to a base model including age, weight and height (MrOS Sweden 0.54 to 0.58, p=0.120; MrOS US 0.57 to 0.59, p=0.057; SOF 0.53 to 0.56, p=0.012; Table 1). No improvement was seen when baseline FN-BMD was also included in the basic model (MrOS Sweden 0.63 to 0.64, p=0.446; MrOS US 0.64 to 0.64, p=0.299; SOF 0.63 to 0.63, p=0.246; Table 1).When tested with the more sensitive IDI and continuous NRI (>0) reclassification metrics, GRS63 significantly but modestly improved the basic model in all cohorts for IDI and NRI (>0; MrOS Sweden 26%, p=0.004; MrOS US 12%, p=0.002; SOF 18%, p<0.001; Table 1). In all cohorts, the increased NRI was the result of a roughly equal contribution from a correct upward reclassification of those with a fracture (6-12%), and a correct downward reclassification of those without a fracture (6-14%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

All Fractures Discrimination and Reclassification

| Discrimination | Reclassification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model C Index | C Index | P value | IDI | event | non-event | P value | NRI | event | non-event | P value | |

| GRS63 SNPs | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||||

| MrOS Sweden | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.120 | 0.011 (0.003-0.019) | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.26 (0.09-0.44) | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.004 |

| MrOS US | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.057 | 0.004 (0.002-0.006) | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.05-0.20) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.002 |

| SOF | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.012 | 0.008 (0.005-0.012) | 0.004 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.11-0.26) | 0.10 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||||

| MrOS Sweden | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.446 | 0.006 (0.000-0.012) | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.22 (0.04-0.40) | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.016 |

| MrOS US | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.299 | 0.001 (0.000-0.002) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.059 | 0.06 (−0.02-0.14) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.145 |

| SOF | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.246 | 0.003 (0.001-0.005) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.11 (0.03-0.19) 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.005 | |

| GRS16 SNPs | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||||

| MrOS Sweden | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.006 | 0.016 (0.007-0.024) | 0.013 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.15-0.50) | 0.19 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| MrOS US | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.350 | 0.001 (0.000-0.002) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.03 (−0.04-0.11) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.389 |

| SOF | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.018 | 0.009 (0.005-0.012) | 0.004 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.11 (0.04-0.19) | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.004 |

| Model 2 | |||||||||||

| MrOS Sweden | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.064 | 0.013 (0.005-0.022) | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.28 (0.11-0.46) | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.002 |

| MrOS US | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.327 | 0.000 (0.000-0.001) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.320 | 0.01 (−0.07-0.09) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.765 |

| SOF | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.052 | 0.006 (0.003-0.009) | 0.003 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.02-0.17) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.018 |

| FN-BMD | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||||

| MrOS Sweden | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.003 | 0.020 (0.011-0.030) | 0.017 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.21-0.55) | 0.28 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| MrOS US | 0.57 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 0.029 (0.024-0.034) | 0.024 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.25-0.40) | 0.21 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| SOF | 0.53 | 0.63 | <0.001 | 0.045 (0.037-0.053) | 0.023 | 0.022 | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.29-0.44) | 0.25 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

Model 1 adjusted according to age, height, weight. Model 2 adjusted according to age, height, weight and baseline femoral neck (FN) BMD. 95% confidence intervals are given within brackets. GRS63 = Genetic risk score based on 63 SNPs. GRS16 = Genetic risk score based on 16 SNPs.

In comparison, when baseline FN-BMD was added to the same base model (age, weight and height) without GRS variables, substantially higher values of NRI and IDI were obtained (NRI: MrOS Sweden: 38%, MrOS US: 33% and SOF: 36%, Table 1).

Importantly, both NRI and IDI for all fractures were considerably attenuated when GRS63 was added to a base model also including FN-BMD (NRI: MrOS Sweden 22%, p=0.016, MrOS US 6%, p=0.145, SOF 11%, p=0.005, Table 1).The same pattern, but with slightly weaker improvements in C-statistics, NRI and IDI, was observed in the hip fracture discrimination and reclassification analyses for the addition of the GRS63 to the base model (Supplemental Table 6).

The GRS16 demonstrated a similar pattern as GRS63 for all fractures discrimination and reclassification, but the GRS16 was inferior to the GRS63 in terms of hip fracture reclassification. (Table 1, Supplemental Table 6).

Sensitivity analyses using unweighted genetic risk scores

Similar but slightly less significant results were found for BMD at both femoral neck and lumbar spine using the unweighted GRS63 risk score. For fracture risk, the results were of similar magnitude for both the unweighted GRS63 and the unweighted GRS16 compared to those found using the corresponding weighted risk scores (Supplemental Table 7 and Supplemental Table 8).

Discussion

BMD and fracture risk are determined both by environmental and genetic factors. Current fracture risk prediction tools are based on clinical risk factors with or without BMD measurements. A recent large-scale meta-analysis identified 63 autosomal SNPs associated with BMD and 16 BMD-associated SNPs were also associated with fracture risk. Based on these findings, two genetic risk scores (GRS63 and GRS16) were developed (15). To determine the clinical utility of these genetic risk scores for the prediction of BMD, BMD change and fracture risk in elderly subjects, three large well-characterized prospective cohorts of older men and women were evaluated. We, herein, demonstrate that the GRS63 is associated with BMD, but not BMD change. The most important finding is that although both the GRS63 and the GRS16 were significantly associated with fracture risk, their clinical utility for fracture discrimination and reclassification is limited when BMD is known.

Twin and family studies have shown a high heritability (50-85%) for BMD. In the most recent publication from the GEFOS consortium, in which the GRS63 was developed and also preliminary evaluated in an independent study of postmenopausal women, it was shown that the GRS63 explained 5.8% of the total genetic variance in BMD (15). In the present study, approximately 3% of the total variance in BMD was explained by the GRS63 and, considering that ≅60% of the total variance in BMD is genetically determined, this would be equal to the GRS63 explaining ≅5% of the total genetic variance, being of the same magnitude as found in the original GEFOS publication (15).

The variance explained in BMD was similar for men and women supporting the idea that men and women share, to a large extent, genetic mechanisms that determine BMD. This could be expected as most individual SNPs included in the GRS63 were significantly associated with BMD in both sexes (15).

Most well-powered twin and family studies demonstrate that there is also a substantial heritability (40-50%) of BMD change (8-10). In the present study, the GRS63 was clearly associated with cross sectional BMD, but not with BMD change. These findings suggest that the genetic influence on BMD change is different from that on peak BMD, highlighting the need for well-powered GWAS meta-analyses on BMD change to identify genetic risk markers related to bone loss.

Estrada et al evaluated the ability of GRS16 to predict prevalent fractures in a cohort of only women (n=2,836; (15)), whereas the present study evaluated the ability of both GRS63 and GRS16 to predict incident fractures in more than 8000 elderly men and women. Estrada et al reported an odds ratio of ≅1.6 for those in the group with the highest risk score (9% of the population) compared to those in the middle group (34% of the population). Using a similar comparison but for incident fractures, we found in the present study an HR of ≅1.4 and ≅1.2 for GRS63 and GRS16, respectively for those in the group with the highest risk score compared to those in the middle group.

After adjustment for FN-BMD, the effect sizes for the associations between the GRS63 and hip fractures (−64%) and all fractures (−50%) were substantially reduced and for hip fracture no longer significant. These findings were to be expected as the SNPs included in the GRS63 were identified based on their association with BMD. The remaining, very modest association between the GRS63 and all fracture risk after BMD adjustment might be the result of the fact that a single BMD measurement does not capture all of the BMD information during lifetime. In the original GEFOS GWAS meta-analysis on BMD, the predictive value of the GRS16, but not the GRS63 was evaluated for fracture risk. Yet, we hypothesized that the GRS63 might capture more of the variation in BMD and thereby more of the fracture risk than the subset of SNPs included in the GRS16, and, therefore, we compared the performance of these two genetic risk scores. The GRS63 explained ≅3% of the variance in FN-BMD in all three cohorts while the GRS16 explained less than 1.0%. This finding was expected as the GRS63 includes nearly four times as many genetic risk markers for BMD compared to the GRS16. For hip fracture the association and reclassification capability of the GRS63 was stronger compared to that of GRS16. It is possible that the difference in hip fracture prediction between the two risk scores could partly be explained in terms of the number of genetic risk markers included, and thus, the amount of variance explained in BMD. However, there was no major difference in prediction capability between the two risk scores for all fractures. Since the GRS63 was clearly associated with fracture risk in non-BMD adjusted models and marginally associated with fracture risk in BMD-adjusted models, we next evaluated its clinical usefulness for fracture discrimination and reclassification in models with or without BMD included. Only minor improvements in C-statistics (AUC) for all fractures were seen when the GRS63 was added to a base model including age, weight and height but not BMD. When tested with the more sensitive IDI and continuous NRI (>0) reclassification metrics, GRS63 significantly, but modestly, improved the base non-BMD-adjusted model in all three cohorts. In each cohort, the increased NRI was the result of a roughly equal contribution from a correct upward reclassification of those with a fracture, and a correct downward reclassification in those without a fracture. Thus in the situation when BMD is unknown, the GRS63 adds statistically significant, but minor information, to fracture discrimination and reclassification. However the GRS63 cannot replace the BMD measurements as FN-BMD was superior to the GRS63 in the discrimination and reclassification of fracture risk.

Since BMD is sometimes known, it is crucial to also evaluate the clinical utility of GRS63 for fracture discrimination and reclassification in a BMD-adjusted base model. No significant improvements in C-statistics for all fractures or hip fractures were seen when GRS63 was added to a base model already including BMD. Similarly, net reclassification improvement was substantially attenuated with the addition of GRS63 to a BMD-adjusted base model, and no or minimal improvements of fracture prediction were observed when IDI, measuring the difference in average predicted probabilities between individuals with and without fractures, was evaluated. In fact, in cases where BMD is not known, a BMD measurement is more informative than an analysis of the SNPs included in the GRSs.

Strengths of the present study include its prospective nature and the fact that it is based on some of the largest available datasets with BMD and well-characterized fractures in both male and female older subjects. A limitation with the present study is that the smaller Gothenburg part (n=942) of MrOS Sweden was included as one of many cohorts in the large (n=50,933) replication phase of the GEFOS meta-analyses and, therefore, only the MrOS US and SOF cohorts are independent samples. As a consequence, the presented effect sizes for MrOS Sweden might be slightly overestimated. Nevertheless, the effect sizes were in the same range for all three cohorts evaluated in the present study, indicating that such a possible overestimation of the effect sizes for MrOS Sweden is marginal. Another limitation with the present study is that only Caucasians were included, and since the genetic background varies for different populations, we cannot generalize our findings to other races or ethnic populations. Also, the follow up time for BMD change in the SOF cohort was only 3.9 years on average, which might have reduced the chance to identify a significant association between BMD change and the GRS63 in this cohort.

In conclusion, this study has shown that the GRS63 predicts BMD, but not BMD change, in older Caucasian participants, suggesting that the genetic determinants of the acquisition of BMD differ from those of BMD change. Both the GRS63 and the GRS16 predict fracture risk. However, if BMD is known, the clinical utility of these genetic risk scores for fracture prediction is limited in older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding:

MrOS Sweden: The MrOS Sweden is supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the ALF/LUA research grant in Gothenburg, the Lundberg Foundation, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg's Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

MrOS US: The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The following institutes provide support: the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AG027810, U01 AG042124, U01 AG042139, U01 AG042140, U01 AG042143, U01 AG042145, U01 AG042168, U01 AR066160, and UL1 TR000128.

Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA): Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1TR000128) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

SOF: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provides support under the following grant numbers: R01 AG005407, R01 AR35582, R01 AR35583, R01 AR35584, R01 AG005394, R01 AG027574, and R01 AG027576. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) provides funding for ‘GWAS in MrOS and SOF’ under the grant number RC2ARO58973.

Role of the funding source: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contribution: Claes Ohlsson and Joel Eriksson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Eriksson, Nielson, Shen, Srikanth, Hochberg, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Acquisition of data: Eriksson, Nielson, Shen, Srikanth, Hochberg, Karlsson, Mellström, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Analysis and interpretation of data: Eriksson, Evans, Shen, Srikanth, Nielson, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Drafting of the manuscript: Eriksson, Nielson, Shen, Srikanth, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Eriksson, Evans, Nielson, Shen, Srikanth, Hochberg, McWeeney, Cawthon, Wilmot, Zmuda, Tranah, Mirel, Challa, Mooney, Crenshaw, Karlsson, Mellström, Vandenput, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Statistical analysis: Eriksson, Evans, Nielson, Shen, Srikanth, Ohlsson

Obtained funding: Orwoll, Ohlsson

Study supervision: Eriksson, Orwoll, Ohlsson

Footnotes

Disclosures

Andrew Crenshaw was an employee of the Broad Institute. Daniel Mirel is an employee of Beckman Coulter Genomics. Beth Wilmot, Carrie Nielson, Peggy Cawthon, Sashi Challa and Michael Mooney have stated that their institution have received grants. Peggy Cawthon also received consultancy fees from Eli Lilly. All other authors state that they have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1994 Aug;9(8):1137–41. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. PubMed PMID: 7976495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohlsson C. Bone metabolism in 2012: Novel osteoporosis targets. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2013 Feb;9(2):72–4. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.252. PubMed PMID: 23296178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen ND, Frost SA, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Development of prognostic nomograms for individualizing 5-year and 10-year fracture risks. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008 Oct;19(10):1431–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0588-0. PubMed PMID: 18324342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008 Apr;19(4):385–97. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. PubMed PMID: 18292978. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2267485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2007 Aug;18(8):1033–46. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. PubMed PMID: 17323110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralston SH, Uitterlinden AG. Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 2010 Oct;31(5):629–62. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0044. PubMed PMID: 20431112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peacock M, Turner CH, Econs MJ, Foroud T. Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocrine reviews. 2002 Jun;23(3):303–26. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0464. PubMed PMID: 12050122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makovey J, Nguyen TV, Naganathan V, Wark JD, Sambrook PN. Genetic effects on bone loss in peri- and postmenopausal women: a longitudinal twin study. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2007 Nov;22(11):1773–80. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070708. PubMed PMID: 17620052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer JR, Kammerer CM, Bruder JM, Cole SA, Dyer TD, Almasy L, et al. Genetic influences on bone loss in the San Antonio Family Osteoporosis study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2008 Dec;19(12):1759–67. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0616-0. PubMed PMID: 18414963. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2712667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhai G, Andrew T, Kato BS, Blake GM, Spector TD. Genetic and environmental determinants on bone loss in postmenopausal Caucasian women: a 14-year longitudinal twin study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2009 Jun;20(6):949–53. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0751-7. PubMed PMID: 18810303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaelsson K, Melhus H, Ferm H, Ahlbom A, Pedersen NL. Genetic liability to fractures in the elderly. Archives of internal medicine. 2005 Sep 12;165(16):1825–30. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.16.1825. PubMed PMID: 16157825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrew T, Antioniades L, Scurrah KJ, Macgregor AJ, Spector TD. Risk of wrist fracture in women is heritable and is influenced by genes that are largely independent of those influencing BMD. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2005 Jan;20(1):67–74. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041015. PubMed PMID: 15619671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner H, Melhus H, Pedersen NL, Michaelsson K. Heritable and environmental factors in the causation of clinical vertebral fractures. Calcified tissue international. 2012 Jun;90(6):458–64. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9592-7. PubMed PMID: 22527201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oei L, Estrada K, Duncan EL, Christiansen C, Liu CT, Langdahl BL, et al. Genome-wide association study for radiographic vertebral fractures: a potential role for the 16q24 BMD locus. Bone. 2014 Feb;59:20–7. PubMed PMID: 24516880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, Hsu YH, Duncan EL, Ntzani EE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nature genetics. 2012 May;44(5):491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. PubMed PMID: 22504420. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3338864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards JB, Rivadeneira F, Inouye M, Pastinen TM, Soranzo N, Wilson SG, et al. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and osteoporotic fractures: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2008 May 3;371(9623):1505–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60599-1. PubMed PMID: 18455228. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2679414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, Richards JB, et al. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nature genetics. 2009 Nov;41(11):1199–206. doi: 10.1038/ng.446. PubMed PMID: 19801982. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2783489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, et al. Multiple genetic loci for bone mineral density and fractures. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 May 29;358(22):2355–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801197. PubMed PMID: 18445777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, et al. New sequence variants associated with bone mineral density. Nature genetics. 2009 Jan;41(1):15–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.284. PubMed PMID: 19079262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timpson NJ, Tobias JH, Richards JB, Soranzo N, Duncan EL, Sims AM, et al. Common variants in the region around Osterix are associated with bone mineral density and growth in childhood. Human molecular genetics. 2009 Apr 15;18(8):1510–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp052. PubMed PMID: 19181680. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2664147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiel DP, Demissie S, Dupuis J, Lunetta KL, Murabito JM, Karasik D. Genome-wide association with bone mass and geometry in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC medical genetics. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S14. PubMed PMID: 17903296. Pubmed Central PMCID: 1995606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mellstrom D, Johnell O, Ljunggren O, Eriksson AL, Lorentzon M, Mallmin H, et al. Free testosterone is an independent predictor of BMD and prevalent fractures in elderly men: MrOS Sweden. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2006 Apr;21(4):529–35. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060110. PubMed PMID: 16598372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, Harper L, Johnson JP, Mitson E, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS). Contemporary clinical trials. 2005 Oct;26(5):557–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. PubMed PMID: 16085466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, Cummings S, Ensrud K, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study--a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemporary clinical trials. 2005 Oct;26(5):569–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. PubMed PMID: 16084776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Mar 23;332(12):767–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. PubMed PMID: 7862179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ensrud KE, Palermo L, Black DM, Cauley J, Jergas M, Orwoll ES, et al. Hip and calcaneal bone loss increase with advancing age: longitudinal results from the study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1995 Nov;10(11):1778–87. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101122. PubMed PMID: 8592956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steiger P, Cummings SR, Black DM, Spencer NE, Genant HK. Age-related decrements in bone mineral density in women over 65. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1992 Jun;7(6):625–32. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070606. PubMed PMID: 1414480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis CE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Shikany JM, Fink HA, Ensrud KE, et al. Predictors of non-spine fracture in elderly men: the MrOS study. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2007 Feb;22(2):211–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061017. PubMed PMID: 17059373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nature genetics. 2012 Aug;44(8):955–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. PubMed PMID: 22820512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hillier TA, Cauley JA, Rizzo JH, Pedula KL, Ensrud KE, Bauer DC, et al. WHO absolute fracture risk models (FRAX): do clinical risk factors improve fracture prediction in older women without osteoporosis? Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011 Aug;26(8):1774–82. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.372. PubMed PMID: 21351144. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3622725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr., D'Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in medicine. 2008 Jan 30;27(2):157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. PubMed PMID: 17569110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delong ER, Delong DM, Clarkepearson DI. Comparing the Areas under 2 or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves - a Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988 Sep;44(3):837–45. PubMed PMID: WOS:A1988Q069100016. English. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.