Background: Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and seven in absentia homolog 1 (Siah1) are molecules associated with stress-signaling cascades.

Results: Identification of Siah1 as a substrate of ASK1 for activation of the GAPDH-Siah1 signaling cascade.

Conclusion: ASK1 triggers the GAPDH-Siah1 stress-signaling cascade.

Significance: This study provides insight into crosstalk among cell stress-signaling cascades.

Keywords: Nuclear Translocation, Oxidative Stress, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Translocation, Protein-Protein Interaction, Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Seven in absentia homolog 1 (Siah1), Apoptosis Signal-regulating Kinase 1 (ASK1)

Abstract

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) plays roles in both energy maintenance, and stress signaling by forming a protein complex with seven in absentia homolog 1 (Siah1). Mechanisms to coordinate its glycolytic and stress cascades are likely to be very important for survival and homeostatic control of any living organism. Here we report that apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), a representative stress kinase, interacts with both GAPDH and Siah1 and is likely able to phosphorylate Siah1 at specific amino acid residues (Thr-70/Thr-74 and Thr-235/Thr-239). Phosphorylation of Siah1 by ASK1 triggers GAPDH-Siah1 stress signaling and activates a key downstream target, p300 acetyltransferase in the nucleus. This novel mechanism, together with the established S-nitrosylation/oxidation of GAPDH at Cys-150, provides evidence of how the stress signaling involving GAPDH is finely regulated. In addition, the present results imply crosstalk between the ASK1 and GAPDH-Siah1 stress cascades.

Introduction

Survival of living organisms is dependent on homeostatic control of both energy maintenance and flexible response to environmental stressors (1–4). In complex living creatures, which are comprised of multiple cells and organs, survival of each cell and elimination of damaged cells becomes important for homeostatic control (5–8). Despite the importance of this fundamental concept, the molecular machinery underlying these mechanisms, and their coordination are not fully understood.

A major mechanism for supplying cellular energy is glycolysis, in which glucose is catabolized to pyruvic acid via several enzymatic reactions. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)3 is a key enzyme in glycolysis, and so plays a major role in cellular energy supply (9). In addition to this classic concept, GAPDH is involved in many subcellular processes that include; DNA repair (10), membrane fusion, and transport (11), tRNA export (12), and cell death (13–19). The functional diversity of GAPDH is largely regulated by its subcellular localization and post-translational modifications (20). Recently studies have revealed that GAPDH can be oxidized and/or S-nitrosylated under stress conditions. Following this post-translational modification GAPDH is then translocated to the nucleus as a complex with Siah1, which has a strong nuclear localization signal (21). Only about 2% of total GAPDH, and a small pool of Siah1 participate in this mechanism, therefore a gain of function by these two molecules due to the specific posttranslational modifications, instead of their loss of functions, is crucial for this signaling cascade (21). In the nucleus, GAPDH modulates several proteins, in particular stimulating the catalytic activity of acetyltransferase p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP) that regulates transcription of various genes (22). Therefore, GAPDH may modulate homeostatic control by bridging energy supply (glycolytic pathway) to stress response (GAPDH-Siah1 cascade), which is finely regulated by post-translational modification (23–26).

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) family. Although cellular substrates of ASK1 have not yet been fully studied, MAPKK4/7 (a kinase that phosphorylates JNK) and MAPKK3/6 that phosphorylates p38 are well-established substrates (27). ASK1 is activated in response to oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and other forms of cellular stress (28, 29). In addition, ASK1 plays pivotal roles in a wide variety of cellular responses, which include, but are not limited to, apoptosis (30, 31). Dysregulation of the ASK1 signaling pathway is closely linked to various diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases including polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration and Parkinson disease (29, 32–37).

The primary focus of the present study is to elucidate regulatory mechanisms of the GAPDH-Siah1 pathway. Here we report that ASK1 phosphorylates Siah1 and critically modulates the GAPDH-Siah1 pathway via direct protein interaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals, Plasmids, and Antibodies

All reagents were purchased from Sigma, unless noted otherwise. cDNA constructs for ASK1 were prepared as previously published (38, 39). GST-tagged-ASK1, GAPDH, and GST only constructs were cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 vector. GST-tagged-Siah1 constructs were cloned into the pGEX-5X-2 vector. HA- and FLAG-tagged-ASK1 constructs were cloned into the pcDNA3 vector. Myc-tagged-Siah1 constructs were cloned into the pRK5 vector. Myc-tagged-Siah1 and its threonine to alanine (T to A) mutants were prepared using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene). Single mutants: M1, mutant with T7A and T11A; M2, mutant with T70A and T74A; M3, mutant with T108A and T112A; and M4, mutant with T235A and T239A. Double mutants were M1+M3 and M2+M4. Recombinant human GAPDH and human ASK1 (amino acids 649–946) were purchased from Sigma and Cell Sciences, respectively. A pSuper shRNA construct was used to knock down the expression of GAPDH (22). The p38 inhibitor SB203580 and JNK inhibitor SP600125 were purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. Antibodies for GAPDH (clones V18 and 6C5), Siah1 (P-18), ASK1 (F-9 and N-19), Myc (9E10), GADD 153 (B3), pThr (H-2), and p300 (C-20) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; ASK-1 (D11C9) and p-c-Jun (S73) were from Cell Signaling Technologies, HA (16B12) was from Clontech, GST (4C10) was from Covance and FLAG (M5) from Sigma; LDH and nuclear matrix protein p84 (5E10) were from Abcam; Ac-p300 (Lys-1499) was from Cell Signaling. HRP-conjugated mouse/rabbit antibodies were from GE Healthcare, and goat HRP was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. [γ-32P]ATP was from Perkin-Elmer.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

The pGEXT vectors carrying GST-tagged-GAPDH, WT ASK1 (aa 1–940), or WT Siah1 were transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α, and the proteins were purified as described (40).

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (50 mm Tris pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, protease inhibitor mixture), co-IPed, and Western blotted as previously described (21, 22). For sequential co-IP studies, the first co-IP reactions with an anti-HA antibody were eluted with HA peptide, elutes were subjected to a subsequent co-IP with anti-Myc antibody. The final co-IP was then subject to Western blot analysis with an anti-FLAG antibody.

Extraction of Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Proteins

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using the Biovision nuclear/cytosol extraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vitro Binding Assays

For ASK1-Siah1 and ASK1-GAPDH in vitro binding assays with equal molar concentrations of GST-tagged-ASK1, Siah1, and His-tagged-GAPDH were incubated in binding buffer (0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm DTT, 10% glycerol, 1 mm PMSF, and 2 μg/ml aprotinin in PBS) for 2 h at 4 °C. For measuring the effects of GAPDH on ASK1-Siah1 binding; 0, 1, and 3 (GAPDH:Siah1) molar concentrations of recombinant GAPDH and Siah1 were incubated in binding buffer, as mentioned above. To obtain recombinant GAPDH and Siah1 without a GST tag, GSH Sepharose-bounded protein was released via thrombin digestion, dialyzed and purity analyzed by Western blot. All in vitro binding assays were done by GST pull-down via incubation with GSH-Sepharose beads (50% slurry) for 1 h, the samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 1 min, washed three times in binding buffer, and resuspended in LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and then heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Western blot analysis of the protein precipitates were done using anti-GAPDH, Siah1, and GST antibodies.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

In vitro phosphorylation assays were performed by 30 min incubation of recombinant Siah1 and GST with or without human recombinant ASK1 (aa 649–946) protein (Cell Sciences) in kinase buffer (4 mm MOPS, pH 7.2, 2.5 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm EDTA, 4 mm MgCl2, 0.05 mm DTT, 40 ng/μl BSA, PIC1 and 2 (Sigma), and 10 mm [γ-32P]ATP). In vitro phosphorylation proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and examined by autoradiography.

p38/JNK Experiments

HEK293 cells expressing HA-GAPDH, Myc-Siah1, and HA-ASK1 were treated with 10–20 μm p38 inhibitor (SB203580) or JNK inhibitor (SP600125) for 0.5–24 h. Cell lysates were subjected to co-IP followed by Western blot as previously described (21, 22).

Statistical Analysis

Two-group analysis was performed by t test (paired or unpaired as appropriate). A value of p < 0.05 is considered significant. All data were obtained from the results of three or four independent experiments.

RESULTS

GAPDH and Siah1 Bind to ASK1 and Form a Ternary Complex in Cells

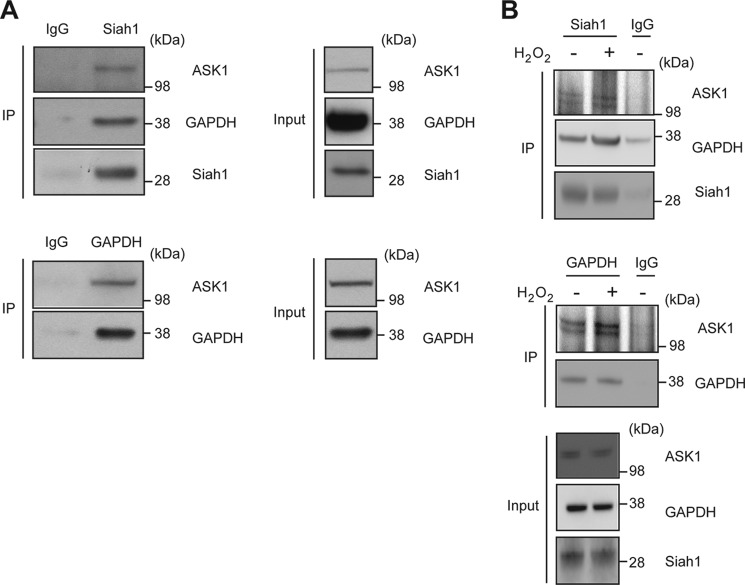

GAPDH-Siah1 and ASK1 have been reported independently to play roles in several pathological brain conditions, and are commonly shown to be key stress mediators (26, 30, 41–43). Thus, we hypothesized that Siah1 and GAPDH might interact with ASK1 at the molecular level. To address this question, we examined mouse brain lysates, and we observed endogenous protein interactions of ASK1-Siah1 and ASK1-GAPDH by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1A). These interactions were also seen and augmented in the presence of H2O2 (1 mm, 30 min) in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Siah1 and GAPDH bind ASK1. A, Siah1-ASK1 and GAPDH-ASK1 binding in mouse brain extracts. Mouse brain extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Siah1 or anti-GAPDH antibodies and analyzed by Western blot with anti-ASK1, GAPDH, and Siah1 antibodies. Input is total cell lysates for immunoprecipitation (IP). B, Siah1-ASK1 binding and GAPDH-ASK1 binding is induced by stress in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 30 min, and protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Siah1, anti-GAPDH, or anti-ASK1 antibodies and analyzed by Western blot with anti-ASK1, GAPDH, and Siah1 antibodies. Input is total cell lysates for IP.

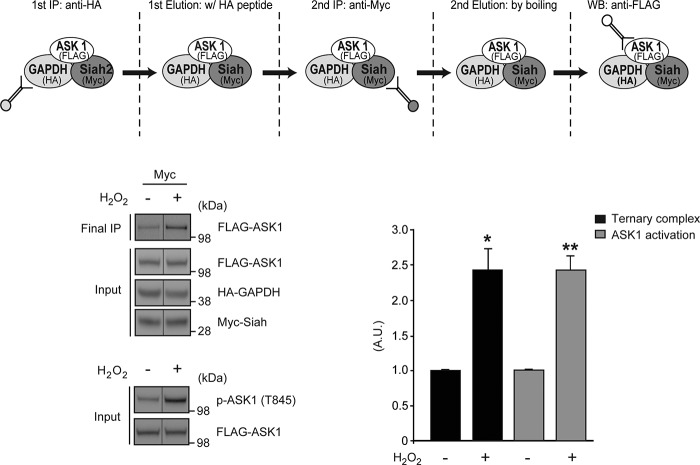

To test whether or not ASK1, Siah1 and GAPDH interact, we performed a sequential co-IP on cell lysates from HEK293 cells expressing ASK1, Siah1, and GAPDH: we observed ASK1-Siah1 and ASK1-GAPDH interaction are induced by treatment with H2O2 (Fig. 2, upper panel). Previous studies have reported stimulation of ASK1 activity by H2O2 (44). To determine if H2O2 stimulated ASK1 activity may induce complex formation we measured ASK1 activity via phosphorylation of ASK1 at Thr-845 and demonstrated that ASK1 activity correlated with ASK1-Siah1-GAPDH complex formation (Fig. 2, lower panel). These results suggest that ASK1, Siah1, and GAPDH form a complex in response to extracellular stressors.

FIGURE 2.

Siah1 and GAPDH form a ternary complex with ASK1 in cells. HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-ASK1, HA-GAPDH, and Myc-Siah1 were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 30 min to induce activation of ASK1 (lower panel). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated in sequence with anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-FLAG antibody (upper panel). Input is the starting material for immunoprecipitation. Ternary complex formation was quantified by densitometric analyses (t test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus FLAG-ASK1).

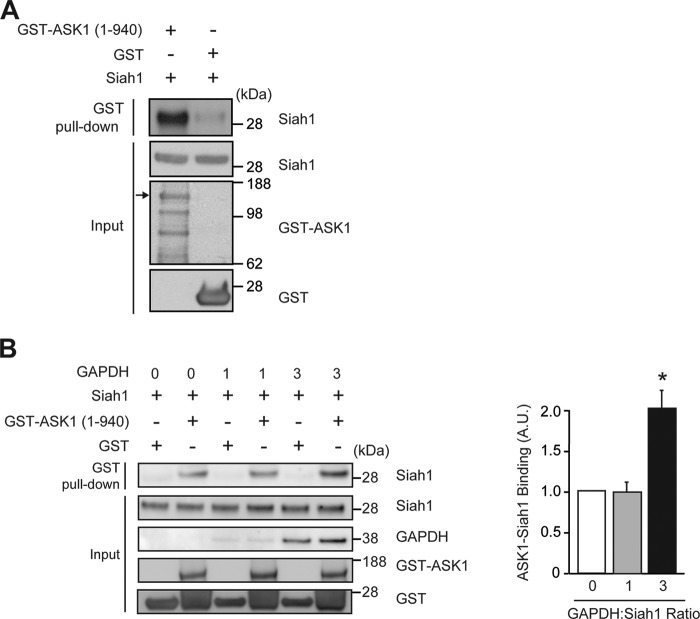

Direct ASK1-Siah1 Interaction and Modulation by GAPDH in Vitro

GAPDH and Siah1 are known to bind directly (21). To characterize the interaction of Siah1 and GAPDH with ASK1 we purified recombinant proteins for in vitro binding studies. Incubation of recombinant Siah1 together with glutathione S-transferase (GST) or GST-tagged-ASK1 (amino acids 1–940) demonstrated that Siah1 binds directly to the N-terminal region of ASK1 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, incubation of recombinant GAPDH together with GST or GST-tagged-ASK1 failed to demonstrate that GAPDH directly binds to ASK1 in vitro (data not shown). Given that stress has been demonstrated to induce direct binding of GAPDH and Siah1 (21), we hypothesized that GAPDH may augment ASK1-Siah1 binding. To determine if GAPDH modulated ASK1-Siah1 binding we performed in vitro binding assays with recombinant Siah1 and ASK1 (amino acids 1–940) in the presence of increasing amounts of GAPDH. These studies demonstrated that a three molar equivalent of GAPDH augmented ASK1-Siah1 direct binding (Fig. 3B). ASK1 (amino acids 1–940) contains the ASK1 kinase domain (649–946) (27).

FIGURE 3.

ASK1 directly binds to Siah1 and is modulated by GAPDH in vitro. A, recombinant GST-ASK1 (aa 1–940) or GST were incubated with recombinant Siah1 in vitro and subjected to GST pull-down, followed Western blot with an anti-Siah1 antibody. Input is the starting material for immunoprecipitation (IP). The input lanes were probed as follows: GST-Siah1 with an anti-Siah1 antibody; GST-ASK1 and GST with an anti-GST antibody. The arrow indicates GST-ASK1 (1–940). B, GAPDH facilitates ASK1-Siah1 binding in vitro. ASK1-Siah1 interaction was assessed by incubating recombinant GST-ASK1 (aa 1–940), or GST with recombinant Siah1 and GAPDH protein at 0, 1, or 3 (GAPDH:Siah1) molar concentrations, followed by to GST pull-down. Precipitates were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Siah1 antibody. Input is the starting material for IP. ASK1-Siah1 binding was quantified by densitometric analyses (t test; *, p < 0.05 versus Siah1).

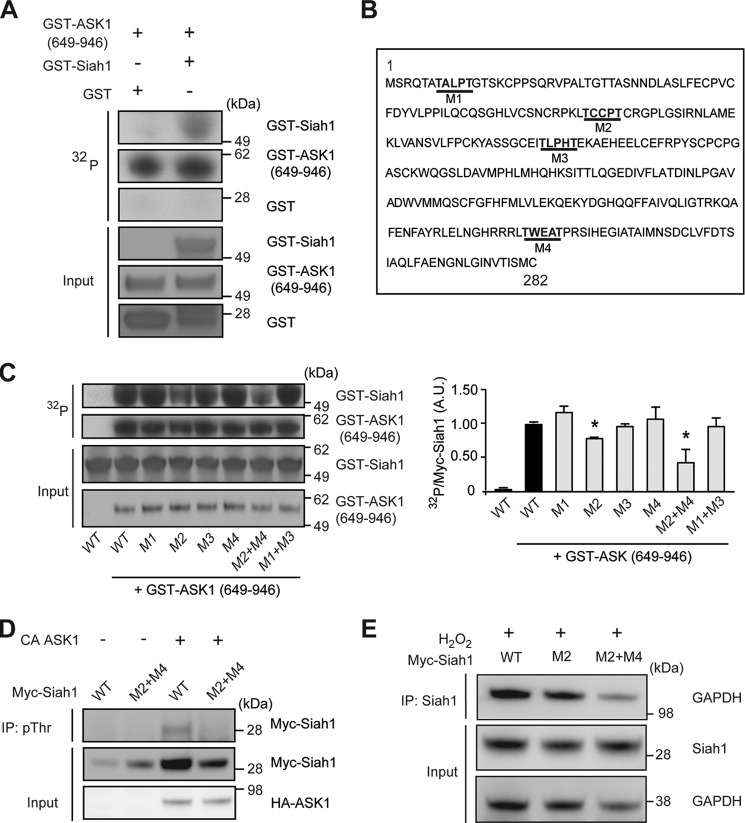

ASK1 Phosphorylates Siah1

Given that Siah1 was determined to directly bind within the kinase domain of ASK1, we hypothesized that Siah1 might be a novel substrate of ASK1 phosphorylation. To investigate whether ASK1 could phosphorylate Siah1, we conducted phosphorylation studies using recombinant proteins in vitro. Phosphorylation of GST-tagged Siah1, but not GST, was observed when Siah1 was incubated with the constitutively active kinase domain of ASK1 (amino acids 649–946) (Fig. 4A). Since ASK1 has been reported to phosphorylate substrates carrying the (S/TXXXS/T) consensus motif (45, 46), we examined the amino acid sequence of Siah1 and identified four potential phosphorylation sites which we designated M1, M2, M3, and M4, respectively (Fig. 4B). To characterize the ASK1 phosphorylation sites on Siah1, we generated mutants of Siah1 with point mutations (threonine to alanine substitution) in each consensus sequence and examined how these mutations affected phosphorylation of Siah1 by ASK1 via in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 4C). Amino acid substitution in M2 led to significant decreases in the phosphorylation of Siah1 by ASK1. However, Siah1 phosphorylation by ASK1 was reduced the most when we introduced mutations at both M2 and M4 (M2+M4) (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that Thr-70/Thr-74, and Thr-235/Thr-239 together are the critical sites in Siah1 phosphorylated by ASK1. We next addressed whether the phosphorylation of Siah1 was induced by ASK1 in cells. To address this question we transfected HEK293 cells with a constitutively kinase activity-positive (CA) ASK1 (amino acids 649–1375) together with WT Siah1 or M2+M4 mutant Siah1 lacking ASK1 phosphorylation sites. The phosphorylation levels of Siah1 were examined by using an anti-Myc antibody after enrichment of proteins with phosphorylation at threonine residues (pThr proteins) by immunoprecipitation with an anti-phosphothreonine antibody. We observed a marked increase in the signal from WT Siah1, but not M2+M4 mutant Siah1, only when co-transfected with CA-ASK1, indicating that Siah1 is phosphorylated at M2+M4 sites by ASK1 (Fig. 4D). At the same time, GAPDH binding with Siah1 was diminished by the replacement of the key threonine residues (the phosphorylation sites of Siah1 by ASK1) to alanine (Fig. 4E): these results suggest thatASK1 kinase activity is crucial for the binding of GAPDH and Siah1, that is, the activation of the GAPDH-Siah1 stress-signaling cascade.

FIGURE 4.

ASK1 phosphorylates Siah1 in cells and in vitro. A, phosphorylation of Siah1 by ASK1 in vitro. In vitro phosphorylation assays were performed by incubation of recombinant GST-Siah1 or GST with constitutively active GST-ASK1 (aa 649–946) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. B, four consensus (S/TXXXS/T) phosphorylation motifs for ASK1 in Siah1 protein: designated as M1, M2, M3, and M4. C, M2+M4 mutant Siah1 shows a significant reduction of phosphorylation by ASK1 in vitro. Labeling with [γ-32P]ATP was carried out in vitro with recombinant GST-ASK1 (aa 649–946), along with several mutant (M1, M2, M3, M4, M2+M4, and M1+M3) Siah1, followed by detection of Siah1 phosphorylation by autoradiography. Input is GST-ASK1 (aa 649–946) and Siah1 in starting material. Siah1 phosphorylation levels were quantified by densitometric analyses (t test; *, p < 0.05 versus WT Siah1). D, phosphorylation levels of Siah1 by ASK1 in cells. HEK293 cells expressing constitutively kinase activity-positive (CA) ASK1 and Myc-Siah1 (WT-Siah1 or M2+M4 mutant Siah1). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti phosphothreonine antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Myc antibody. Representative Western blots were shown: the levels of Siah1 phosphorylation were calculated after subdividing the band intensity of the Myc-Siah signal in immunoprecipitation (IP) by the intensity in the input [WT, 1; M2+M4, 0.20 ± 0.17; WT and CA ASK1, 1.63 ± 1.00; M2+M4 and CA ASK1, 0.40 ± 0.22, mean ± S.D., n = 3]. E, M2 and M2+M4 Siah1 mutants exhibit reduced binding to GAPDH. HEK293 cells expressing WT-Siah1, M2 or M2+M4 Siah1 mutants were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Siah1 antibody and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-GAPDH antibody. Representative Western blots were shown: the levels of GAPDH were calculated after subdividing the band intensity of the GAPDH signal in IP by the intensities of the GAPDH and Siah in the input [WT, 1; M2, 0.89 ± 0.39; M2+M4, 0.55 ± 0.35, mean ± S.D., n = 3].

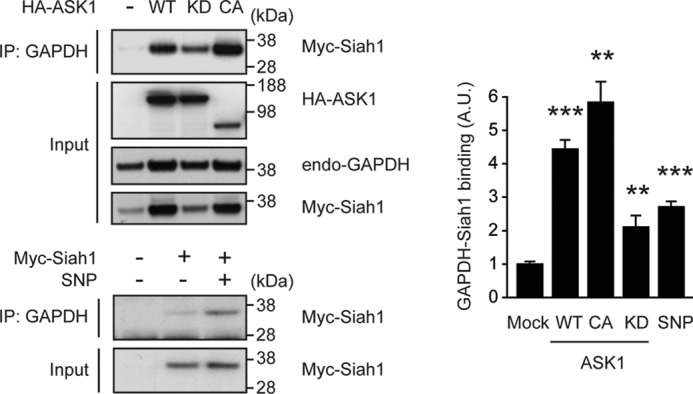

ASK1 Augments GAPDH-Siah1 Binding in Cells

We next addressed whether ASK1 modulates GAPDH-Siah1 signaling. Thus, we introduced wild-type (WT) ASK1, kinase-dead (KD) ASK1 that was generated with one amino acid substitution at 709 (K709M), and constitutively kinase activity-positive (CA) ASK1 (see above) in cells, respectively (39). We then examined how these distinct forms of ASK1 affected GAPDH-Siah1 binding. We previously reported that sodium nitroprusside (a nitric oxide donor) could affect GAPDH-Siah1 binding by S-nitrosylation of GAPDH (21), which was used as a reference of the binding change. Introduction of WT ASK1 dramatically augmented GAPDH-Siah1 binding, which was considerably greater than the change elicited by sodium nitroprusside in total cell lysates (Fig. 5, lower panel). When kinase activity of ASK1 was selectively reduced (KD ASK1), such augmentation was also reduced. Consistent with this observation, introduction of CA ASK1 also dramatically augmented GAPDH-Siah1 binding. In all the conditions, the levels of GAPDH-Siah1 binding were normalized by the levels of Myc-Siah1 (Fig. 5, upper panel). Note, the levels of Siah1 are affected by expression of different types of ASK1 constructs. These results suggest that ASK1, especially its kinase activity, is critical in augmenting GAPDH-Siah1 protein binding.

FIGURE 5.

ASK1 facilitates GAPDH-Siah1 binding in cells. Upper panel, ASK1 augments GAPDH-Siah1 binding in a kinase-dependent manner. Cell lysates of HEK293 cells expressing Myc-tagged wild-type (WT) Siah1 together with HA-WT ASK1, kinase-dead (KD) ASK1, or constitutively active (CA) ASK1, were immunoprecipitated with an anti-GAPDH antibody and analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Myc antibody (for Siah1). Input is the total cell lysates. Lower panel, sodium nitroprusside (SNP, a nitric oxide donor) elicits an augmented GAPDH-Siah1 binding. HEK293 cells overexpressing Myc-WT Siah1 were treated with SNP, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-GAPDH antibody and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Myc (Siah1) antibody. Input is Myc-Siah1 in total cell lysates. Western blots were quantified by densitometric analyses. Y axis depicts the level of GAPDH-Siah1 binding that was normalized by the levels of Siah1. (t test; **, p < 0.01 and ***, p < 0.001 versus Mock).

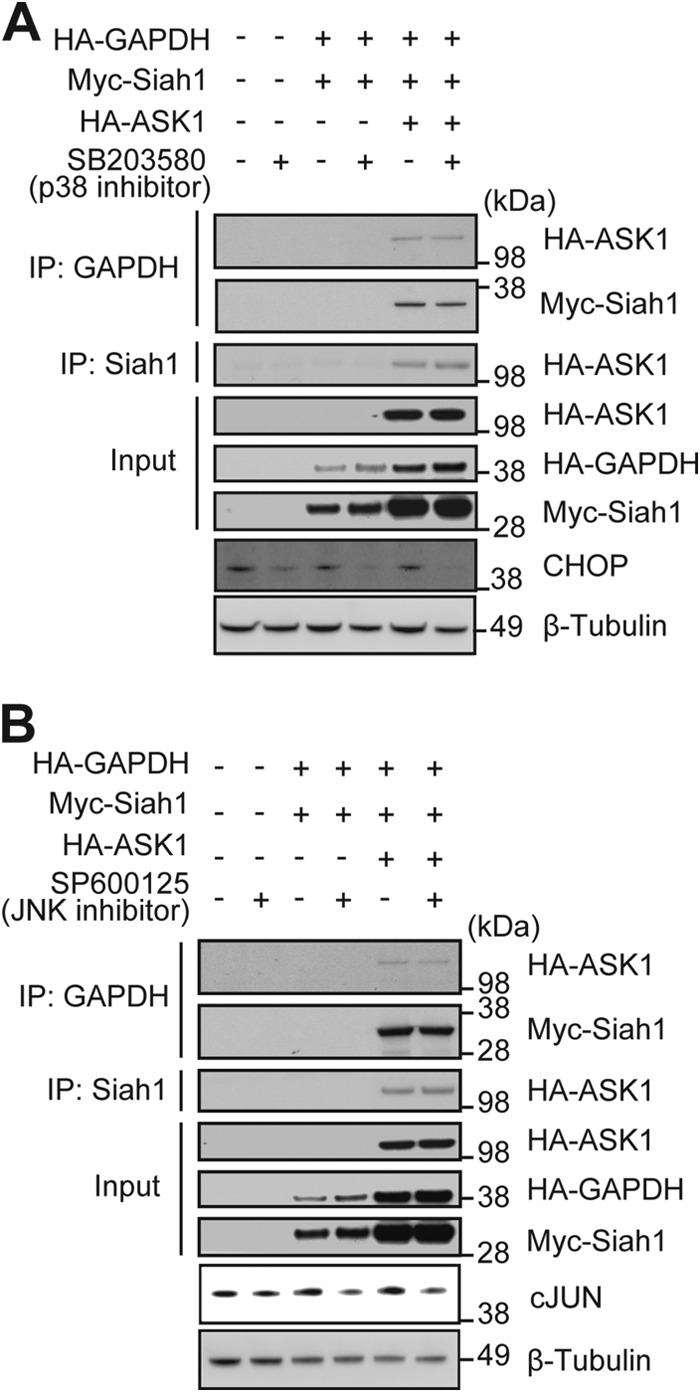

ASK1-induced GAPDH-Siah1 Binding in Cells Is Independent of p38 and JNK Signaling

We considered the possibility that increased GAPDH-Siah1 binding could be affected by JNK and p38, two key kinases downstream of ASK1 (27). To test this idea, we used specific kinase inhibitors (SB203580 specific for p38 and SP600125 specific for JNK) and examined the effects on GAPDH-Siah1 binding in the presence of exogenous WT ASK1. Neither SB203580 nor SP600125 affected ASK1-GAPDH, ASK1-Siah1, and GAPDH-Siah1 interactions (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting that ASK1-induced GAPDH-Siah1 binding occurs independent to p38/JNK signaling.

FIGURE 6.

GAPDH-Siah1 binding is independent of p38 and JNK signaling. GAPDH-Siah1-ASK1 interactions occur independent of p38 and JNK activation. A, representative figure in which GAPDH-Siah1-ASK1 interactions were assessed in lysates from HEK293 treated with 10 μm p38-specific inhibitor (SB203580) followed by the immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot with indicated antibodies. Input is expression of HA-ASK1, HA-GAPDH and Myc-Siah1 in total cell lysates. B, representative figure in which GAPDH-Siah1-ASK1 interaction assessed in HEK293 cells treated with 10 μm JNK-specific inhibitor (SP600125) followed by the IP and Western blot with indicated antibodies. Input is expression of HA-ASK1, HA-GAPDH, and Myc-Siah1 in total cell lysates.

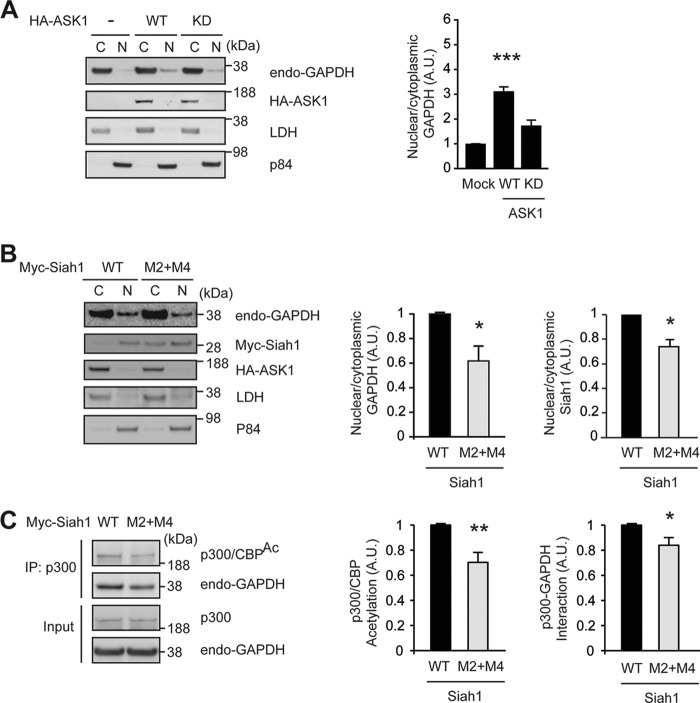

ASK1 Augments Nuclear Translocation of GAPDH and p300 Acetylation in Cells

The major event of activated GAPDH-Siah1 stress signaling is translocation of GAPDH (21). Thus, we questioned whether ASK1 might facilitate the nuclear translocation, and tested the effects of WT or KD ASK1. We observed robust levels of nuclear translocation of GAPDH in the presence of exogenous WT ASK1, whereas introduction of KD ASK1 did not elicit significant levels of GAPDH translocation (Fig. 7A). We further tested whether this translocation by ASK1 was related to phosphorylation of Siah1. In the presence of ASK1 the complex of GAPDH and mutant Siah1 (M2+M4 mutant; lacking ASK1 phosphorylation sites) displayed significantly reduced nuclear translocation compared with the complex of WT Siah1 and GAPDH (Fig. 7B). We then questioned whether these Siah1 mutations (M2+M4) critically affect nuclear functions in ASK1-triggered GAPDH-Siah1 stress signaling. Thus, we examined GAPDH-p300 binding and acetylation of p300, which have been established as good functional indicators in the nucleus (22). Western blot analysis revealed a significant decrease in p300-GAPDH binding and acetylation of p300, which can be interpreted as a key consequence of reduction in nuclear translocation of GAPDH with the mutant Siah1 (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

ASK1 augments nuclear translocation of GAPDH and p300 acetylation in cells. A, ASK1 augments nuclear translocation of GAPDH in a kinase-dependent manner. Effects of ASK1 kinase activity on nuclear translocation of GAPDH were examined in HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged WT or KD ASK1, followed by cellular fractionation and Western blot quantification of GAPDH nuclear/cytoplasmic ratios. GAPDH signals were normalized by LDH (a cytoplasmic marker) and P84 (a nuclear marker) (t test; ***, p < 0.001 versus Mock). B, M2+M4 phosphorylation sites of Siah1 by ASK1 are critical to induce nuclear translocation of GAPDH. HEK293 cells expressing HA-WT ASK1 together with Myc-tagged WT or M2+M4 mutant Siah1 were subjected to subcellular fractionation. Nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of GAPDH or Siah1 was analyzed in cells expressing WT or M2+M4 mutant. The ratios of both endogenous GAPDH and exogenous myc-Siah1 were reduced in cells expressing M2+M4 mutant compared with those expressing WT Siah1 (t test; *, p < 0.05 versus WT-Siah1). C, M2 and M4 phosphorylation sites of Siah1 by ASK1 are required for acetylation of p300 and p300-GAPDH interaction. Lysates of HEK293 cells expressing HA-WT ASK1 together with Myc-WT Siah1 or M2+M4 mutant Siah1 were immunoprecipitated with an anti-p300 antibody and analyzed by Western blot with acetyl-p300 (Lys-1499)/CBP (Lys-1535) (p300/CBPAc) and GAPDH antibodies. Input is endogenous p300 and GAPDH in total cell lysates. Western blots were quantified by densitometric analyses (t test; *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 versus WT Siah1).

To address functional outcome downstream of P300-GAPDH, we applied H2O2 (1 mm, 30 min) to HEK293 cells and examined expression of PUMA, which is known as a representative target of P300-GAPDH activation (22). Under these conditions we observed a significant reduction of PUMA levels in the cells that expressed M2±M4 mutant Siah1 deficient in ASK1 phosphorylation sites, compared with the cells with wild-type Siah1 (Fig. 8). These results suggest that phosphorylation of Siah1 by ASK1 is likely to play a key role in the GAPDH-Siah1 signaling cascade and subsequent functional effects in the nucleus.

FIGURE 8.

PUMA expression, a downstream target of p300, was found reduced in M2+M4 mutant of Siah1. HEK293 cells expressing WT-Siah1 and M2+M4 Siah1 mutants were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 30 min. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-PUMA antibody. The y axis depicts the level of PUMA that was normalized by the levels of Siah1. (t test; ***, p < 0.001.)

DISCUSSION

Cellular signaling in response to stressors is crucial in homeostatic control and survival of all organisms. Thus, crosstalk among signaling cascades and their finely tuned regulation are expected. In the present study, we show that ASK1, a representative stress kinase, regulates GAPDH-Siah1 signaling. We demonstrate that ASK1 binds with GAPDH and Siah1: these bindings are augmented under oxidative stress and are likely to be the basis of this signal network. We have identified Siah1 is a novel substrate of ASK1, with Thr-70/Thr-74 and Thr-235/Thr-239, as the critical phosphorylation sites on Siah1. Phosphorylation by ASK1 was found to increase GAPDH-Siah1 binding, its nuclear translocation, and subsequent acetylation of nuclear P300 and PUMA expression.

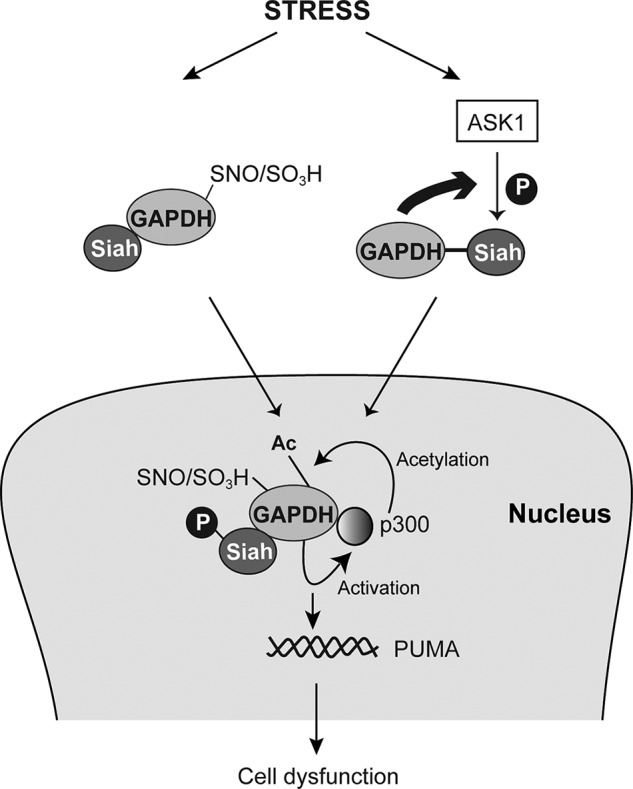

Thus far, a specific post-translational modification of GAPDH (S-nitrosylation/oxidation at Cys-150) had been established as an initial trigger of GAPDH-Siah1 signaling (21). In the present study we show that specific post-translational modifications of Siah1, the other partner of this complex, can also be a trigger of this cascade (Fig. 9). ASK1 is activated in response to various stressors, such as oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress, it is likely that Siah1 is subsequently phosphorylated and mediates stress signaling by forming a complex with GAPDH. Thus, this study establishes the notion that the GAPDH-Siah1 cascade is activated by more than one mechanism in the presence of various cellular stressors. This cascade is also inhibited by at least two mechanisms: both interaction with a cytosolic protein GOSPEL (47) and a set of deprenyl-related compounds (40). It is likely that the GAPDH-Siah1 cascade, which is crucial for homeostatic control, has multiple mechanisms that regulate its initiation in both positive and negative ways. It will be interesting to clarify how these two distinct post-translational modifications (oxidation of GAPDH and phosphorylation of Siah1) are coordinated under different types of stress. Given that both ASK1 and GAPDH-Siah1 cascades are major routes of stress signaling, an important future question is to understand how GAPDH-Siah1 can also influence ASK1.

FIGURE 9.

Scheme to represent the mechanisms through GAPDH-Siah1 pathway is activated under stress.

Here we demonstrate that ASK1 and GAPDH-Siah1 co-mediate stress signaling and up-regulate p300. It is known that p300 has multiple functions in different conditions: for example, in the heart p300 activation can lead to heart hypertrophy mediated by myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) (48), whereas in the brain p300 affects memory function via cAMP response element-binding (CREB) (49). Roles for stressors in these conditions are appreciated, but further molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Thus, new generation of conditional knock-out mice or inducible transgenic models targeting these molecules will be crucial to test context-dependent crosstalk of ASK1 and GAPDH-Siah1. As far as we are aware, such mice are not available at present. Better understanding of the crosstalk between these two stress cascades (ASK1 and GAPDH-Siah1) may provide a more integrated and comprehensive picture of how our body responds to stressors in a context-dependent fashion and how disturbances of such mechanisms may lead to pathological conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Koko Ishizuka, Makoto Hara, and Srinivasa Subramaniam for technical support.

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants MH-084018 (to A. S.), MH-094268 Silvo O. Conte Center (to A. S.), MH-069853 (to A. S.), MH-085226 (to A. S.), MH-088753 (to A. S.), MH-092443 (to A. S.), National Institutes of Health NRSA F31 Grant 1F31NS070459-01A1 (to C. T.), Stanley (to A. S.), RUSK (to A. S.), S-R foundations (to A. S.), NARSAD (to A. S. and N. S.), and Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (A. S.). This work was also supported in part by Grant-in-aid 22580339 for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the promotion of Science (to H. N).

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- ASK

- apoptosis signal-regulating kinase

- Siah

- seven in absentia homolog.

REFERENCES

- 1. Langley L. L. (1973) Homeostasis: Origins of the Concept, Dowden, Stroudsburg, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schulkin J. (2003) Rethinking Homeostasis : Allostatic Regulation in Physiology and Pathophysiology, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schulkin J. (2004) Allostasis, Homeostasis and the Costs of Physiological Adaptation, Cambridge University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiras D. D. (2010) Human Biology, 7th ed., Jones & Bartlett Learning, Sudbury, MA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fulda S., Gorman A. M., Hori O., Samali A. (2010) Cellular stress responses: cell survival and cell death. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koga H., Kaushik S., Cuervo A. M. (2011) Protein homeostasis and aging: The importance of exquisite quality control. Ageing Res. Rev. 10, 205–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mizushima N., Komatsu M. (2011) Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147, 728–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeda K., Naguro I., Nishitoh H., Matsuzawa A., Ichijo H. (2011) Apoptosis signaling kinases: from stress response to health outcomes. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 15, 719–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voet D., Voet J. G. (2011) Biochemistry, 4th Ed., John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meyer-Siegler K., Mauro D. J., Seal G., Wurzer J., deRiel J. K., Sirover M. A. (1991) A human nuclear uracil DNA glycosylase is the 37-kDa subunit of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 8460–8464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tisdale E. J. (2001) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is required for vesicular transport in the early secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2480–2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh R., Green M. R. (1993) Sequence-specific binding of transfer RNA by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Science 259, 365–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chuang D. M., Ishitani R. (1996) A role for GAPDH in apoptosis and neurodegeneration. Nat. Med. 2, 609–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishitani R., Chuang D. M. (1996) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antisense oligodeoxynucleotides protect against cytosine arabinonucleoside-induced apoptosis in cultured cerebellar neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9937–9941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishitani R., Kimura M., Sunaga K., Katsube N., Tanaka M., Chuang D. M. (1996) An antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase blocks age-induced apoptosis of mature cerebrocortical neurons in culture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 278, 447–454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saunders P. A., Chalecka-Franaszek E., Chuang D. M. (1997) Subcellular distribution of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cerebellar granule cells undergoing cytosine arabinoside-induced apoptosis. J. Neurochem. 69, 1820–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colell A., Ricci J. E., Tait S., Milasta S., Maurer U., Bouchier-Hayes L., Fitzgerald P., Guio-Carrion A., Waterhouse N. J., Li C. W., Mari B., Barbry P., Newmeyer D. D., Beere H. M., Green D. R. (2007) GAPDH and autophagy preserve survival after apoptotic cytochrome c release in the absence of caspase activation. Cell 129, 983–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ou X. M., Stockmeier C. A., Meltzer H. Y., Overholser J. C., Jurjus G. J., Dieter L., Chen K., Lu D., Johnson C., Youdim M. B., Austin M. C., Luo J., Sawa A., May W., Shih J. C. (2010) A novel role for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and monoamine oxidase B cascade in ethanol-induced cellular damage. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 855–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sawa A., Khan A. A., Hester L. D., Snyder S. H. (1997) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: nuclear translocation participates in neuronal and nonneuronal cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 11669–11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sirover M. A. (2012) Subcellular dynamics of multifunctional protein regulation: Mechanisms of GAPDH intracellular translocation. J. Cell Biochem. 113, 2193–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hara M. R., Agrawal N., Kim S. F., Cascio M. B., Fujimuro M., Ozeki Y., Takahashi M., Cheah J. H., Tankou S. K., Hester L. D., Ferris C. D., Hayward S. D., Snyder S. H., Sawa A. (2005) S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 665–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sen N., Hara M. R., Kornberg M. D., Cascio M. B., Bae B. I., Shahani N., Thomas B., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., Snyder S. H., Sawa A. (2008) Nitric oxide-induced nuclear GAPDH activates p300/CBP and mediates apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 866–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shahani N., Sawa A. (2012) Protein S-nytrosylation: Role for nitric oxide signaling in neuronal death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 736–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shahani N., Sawa A. (2011) Nitric oxide signaling and nitrosative stress in neurons: role for S-nitrosylation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 14, 1493–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sirover M. A. (2011) On the functional diversity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: biochemical mechanisms and regulatory control. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1810, 741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tristan C., Shahani N., Sedlak T. W., Sawa A. (2011) The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell Signal 23, 317–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ichijo H., Nishida E., Irie K., ten Dijke P., Saitoh M., Moriguchi T., Takagi M., Matsumoto K., Miyazono K., Gotoh Y. (1997) Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 275, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu Y., Richardson D. R. (2011) Cellular iron depletion stimulates the JNK and p38 MAPK signaling transduction pathways, dissociation of ASK1-thioredoxin, and activation of ASK1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15413–15427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cho K. J., Lee B. I., Cheon S. Y., Kim H. W., Kim H. J., Kim G. W. (2009) Inhibition of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress and nuclear huntingtin fragments in a mouse model of Huntington disease. Neuroscience 163, 1128–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hattori K., Naguro I., Runchel C., Ichijo H. (2009) The roles of ASK family proteins in stress responses and diseases. Cell Commun. Signal 7, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Homma K., Katagiri K., Nishitoh H., Ichijo H. (2009) Targeting ASK1 in ER stress-related neurodegenerative diseases. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 13, 653–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishitoh H., Matsuzawa A., Tobiume K., Saegusa K., Takeda K., Inoue K., Hori S., Kakizuka A., Ichijo H. (2002) ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 16, 1345–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Izumiya Y., Kim S., Izumi Y., Yoshida K., Yoshiyama M., Matsuzawa A., Ichijo H., Iwao H. (2003) Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 plays a pivotal role in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Circ. Res. 93, 874–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Imoto K., Kukidome D., Nishikawa T., Matsuhisa T., Sonoda K., Fujisawa K., Yano M., Motoshima H., Taguchi T., Tsuruzoe K., Matsumura T., Ichijo H., Araki E. (2006) Impact of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 on insulin signaling. Diabetes 55, 1197–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iriyama T., Takeda K., Nakamura H., Morimoto Y., Kuroiwa T., Mizukami J., Umeda T., Noguchi T., Naguro I., Nishitoh H., Saegusa K., Tobiume K., Homma T., Shimada Y., Tsuda H., Aiko S., Imoto I., Inazawa J., Chida K., Kamei Y., Kozuma S., Taketani Y., Matsuzawa A., Ichijo H. (2009) ASK1 and ASK2 differentially regulate the counteracting roles of apoptosis and inflammation in tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 28, 843–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayakawa Y., Hirata Y., Nakagawa H., Sakamoto K., Hikiba Y., Kinoshita H., Nakata W., Takahashi R., Tateishi K., Tada M., Akanuma M., Yoshida H., Takeda K., Ichijo H., Omata M., Maeda S., Koike K. (2011) Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 and cyclin D1 compose a positive feedback loop contributing to tumor growth in gastric cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 780–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsu M. J., Hsu C. Y., Chen B. C., Chen M. C., Ou G., Lin C. H. (2007) Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in amyloid beta peptide-induced cerebral endothelial cell apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 27, 5719–5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saitoh M., Nishitoh H., Fujii M., Takeda K., Tobiume K., Sawada Y., Kawabata M., Miyazono K., Ichijo H. (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 17, 2596–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang H. Y., Nishitoh H., Yang X., Ichijo H., Baltimore D. (1998) Activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) by the adapter protein Daxx. Science 281, 1860–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hara M. R., Thomas B., Cascio M. B., Bae B. I., Hester L. D., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Sawa A., Snyder S. H. (2006) Neuroprotection by pharmacologic blockade of the GAPDH death cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3887–3889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chuang D. M., Hough C., Senatorov V. V. (2005) Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, apoptosis, and neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 45, 269–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tatton N. A. (2000) Increased caspase 3 and Bax immunoreactivity accompany nuclear GAPDH translocation and neuronal apoptosis in Parkinson's disease. Exp. Neurol. 166, 29–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tatton W. G., Chalmers-Redman R., Brown D., Tatton N. (2003) Apoptosis in Parkinson's disease: signals for neuronal degradation. Ann. Neurol. 53, S61–S70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seong H. A., Jung H., Manoharan R., Ha H. (2011) Positive regulation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 signaling by ZPR9 protein, a zinc finger protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31123–31135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. He X., Liu Y., Sharma V., Dirksen R. T., Waugh R., Sheu S. S., Min W. (2003) ASK1 associates with troponin T and induces troponin T phosphorylation and contractile dysfunction in cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 163, 243–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bunkoczi G., Salah E., Filippakopoulos P., Fedorov O., Müller S., Sobott F., Parker S. A., Zhang H., Min W., Turk B. E., Knapp S. (2007) Structural and functional characterization of the human protein kinase ASK1. Structure 15, 1215–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sen N., Hara M. R., Ahmad A. S., Cascio M. B., Kamiya A., Ehmsen J. T., Aggrawal N., Hester L., Doré S., Snyder S. H., Sawa A. (2009) GOSPEL: a neuroprotective protein that binds to GAPDH upon S-nitrosylation. Neuron 63, 81–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei J. Q., Shehadeh L. A., Mitrani J. M., Pessanha M., Slepak T. I., Webster K. A., Bishopric N. H. (2008) Quantitative control of adaptive cardiac hypertrophy by acetyltransferase p300. Circulation 118, 934–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oliveira A. M., Wood M. A., McDonough C. B., Abel T. (2007) Transgenic mice expressing an inhibitory truncated form of p300 exhibit long-term memory deficits. Learn Mem. 14, 564–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]