Abstract

Significance: The brain has high energetic requirements and is therefore highly dependent on adequate cerebral blood supply. To compensate for dangerous fluctuations in cerebral perfusion, the circulation of the brain has evolved intrinsic safeguarding measures. Recent Advances and Critical Issues: The vascular network of the brain incorporates a high degree of redundancy, allowing the redirection and redistribution of blood flow in the event of vascular occlusion. Furthermore, active responses such as cerebral autoregulation, which acts to maintain constant cerebral blood flow in response to changing blood pressure, and functional hyperemia, which couples blood supply with synaptic activity, allow the brain to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion in the face of varying supply or demand. In the presence of stroke risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, these protective processes are impaired and the susceptibility of the brain to ischemic injury is increased. One potential mechanism for the increased injury is that collateral flow arising from the normally perfused brain and supplying blood flow to the ischemic region is suppressed, resulting in more severe ischemia. Future Directions: Approaches to support collateral flow may ameliorate the outcome of focal cerebral ischemia by rescuing cerebral perfusion in potentially viable regions of the ischemic territory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 149–160.

Introduction

The brain is an extremely energy demanding organ. Despite representing only ∼2% of body mass, it consumes ∼20% of the total energy in a resting state. At the same time, the brain has limited intracellular energy reserves, and therefore, proper functioning is highly dependent on cerebral blood supply and the continuous delivery of glucose and oxygen. Due to these high energetic requirements, the brain has evolved a number of protective mechanisms to safeguard against dangerous fluctuations in blood supply. However, under certain pathological conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and after ischemic stroke, these protective mechanisms are compromised, resulting in an increased vulnerability of the brain to cellular dysfunction and death. In this article, we will review the mechanisms regulating cerebral perfusion and discuss alterations that occur due to both the presence of risk factors for stroke and after an ischemic event.

Safeguarding the Brain Against Impaired Perfusion

Cerebral vascular anatomy

The vascular network of the brain has unique structural features, aimed at preventing reductions in cerebral perfusion in response to vascular occlusion (22, 34). At a large scale, redundancy is introduced at the level of the circle of Willis. This poligonal arterial structure is situated at the base of the brain and is formed by the merging of the vertebral arteries, basilar artery, and internal carotid arteries. In the event of a blockage within the circle or a reduced supply by feeding arteries, the blood flow can be reversed, effectively redirecting the blood supply and ensuring adequate delivery to downstream vessels. The second major level of redundancy is formed by the pial network of cerebral surface vessels, particularly, branches of the anterior communicating artery, middle cerebral artery (MCA), posterior cerebral artery, and anterior choroidal artery. These arteries originate at the circle of Willis and extend to span the exterior surface of the brain, forming extensive anastomoses and providing a vast, interconnected vascular network (14, 15). From here, penetrating arteries form and enter the brain parenchyma perpendicularly, thereby supplying blood to the gray matter of the cortex. Interestingly, penetrating arteries account for ∼1/3 of the vascular resistance in the brain, while pial arteries account for ∼2/3, indicating that the surface vessels have the largest impact on blood supply to the brain (27). Consistent with this, microinfarcts have been shown to occur in response to occlusion of a single penetrating vessel (either venule or arteriole), whereas due to heavy collateralization, blood flow is maintained and minimal tissue injury induced following occlusion of a single vessel of the superficial arterial network (56, 57, 67, 69). In contrast to the cortex, perfusion of the striatum is provided by small terminal lenticulostriate arteries, and thus, this region has an increased susceptibility to ischemic injury due to the lack of collateral perfusion.

Cerebral vascular function

Functional hyperemia

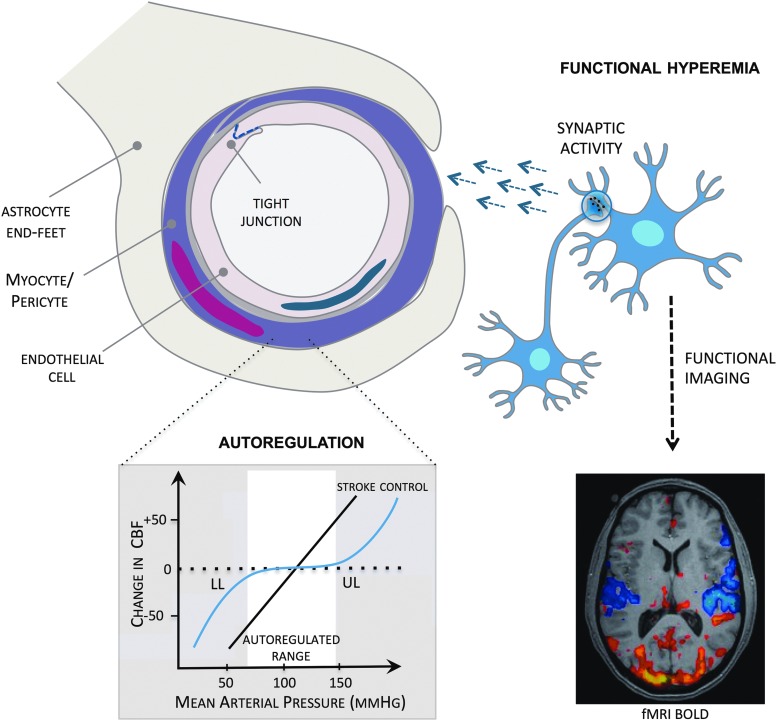

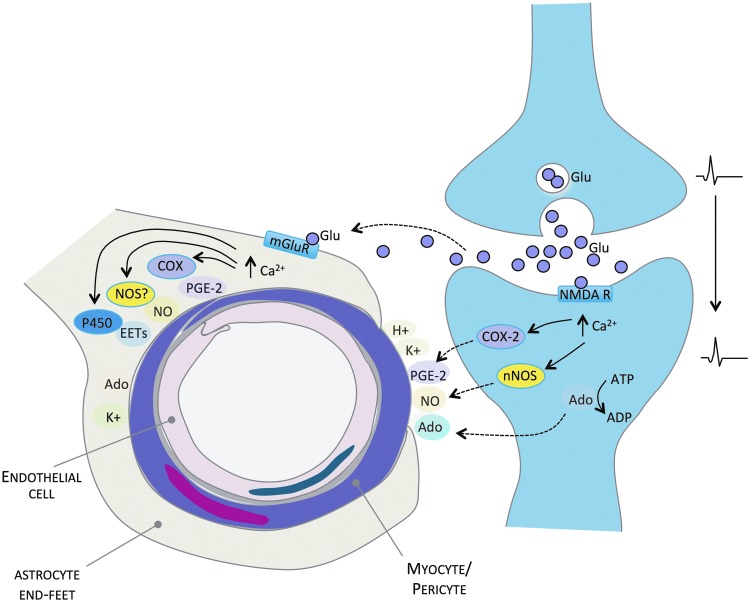

In the brain, neural activity is closely coupled to the degree of vascular perfusion. This process, known as functional hyperemia or neurovascular coupling, actively pairs blood supply both spatially and temporally to specific regions of the brain based on the degree of synaptic activity (38) (Figs. 1 and 2). Whereas the precise mechanism of communication between blood vessels and neurons remains to be established, it is widely accepted to occur in response to activation of glutamate receptors during synaptic transmission, increasing postsynaptic calcium (Ca2+) and the subsequent release of vasoactive agents. Several vasoactive agents have been linked to this process and are reviewed in detail in several excellent reviews (25, 31, 40). They include vasoactive potassium (K+) and hydrogen ions, metabolic factors, including lactate, carbon dioxide and adenosine, neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, GABA, and acetylcholine), nitric oxide (NO) synthesized by neuronal NO synthase (nNOS), and prostaglandin production by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Fig. 2). Whereas neurons may signal directly to blood vessels to initiate functional changes in flow, astrocytes are now believed to play a central role in this process (40, 73, 83). Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors on astrocytic end feet results in increased intracellular Ca2+, COX-induced prostaglandin production, the release of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids from cytochrome P450 epoxygenase, and production of NO by NOS (Fig. 2). In addition, K+ is released by astrocytes during spatial buffering. However, the mechanisms of communication between the cerebral vasculature and neurons are highly complex and recent studies continue to refine our current understanding of this process (21, 74).

FIG. 1.

Major factors regulating the cerebral circulation. Endothelial regulation: endothelial cells release vasoactive mediators that act on underlying smooth muscle cells. In addition, the interaction of adjacent endothelial cells forms tight junctions—the primary site of the blood–brain barrier. Functional hyperemia actively pairs cerebral blood flow to changes in neural activity. Synaptic activity stimulates the release of signaling molecules that initiate changes in vascular tone. Functional hyperemia forms the basis of functional brain imaging. Cerebrovascular autoregulation maintains relatively constant cerebral perfusion in the face of changes in mean arterial pressure. Autoregulation is impaired following cerebral ischemia such that blood flow follows pressure in a linear fashion, increasing risk of dangerous levels of hypo- and hyperperfusion. CBF, cerebral blood flow; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; BOLD, blood oxygenation level dependent; LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

FIG. 2.

Mechanisms of functional hyperemia. Neural activity releases Glu from presynaptic terminals. Glu, in turn, is thought to activate NMDA receptors on postsynaptic neurons and mGluR located on perivascular astrocytes. Stimulation of these receptors increases intracellular Ca2+, activating enzymes such as COX, NOS, and cytochrome P450 epoxygenases, and causing the release of vasoactive mediators, such as PGE-2, NO, and EETs, which act to relax smooth muscle cells, increasing CBF. In addition, Ado, K+, and H+ ions are released and act directly on vascular smooth muscles to initiate increases in CBF. Ado, adenosine; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Ca2+, calcium; CBF, cerebral blood flow; COX, cyclooxygenase; EETs, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; Glu, glutamate; H+, hydrogen; K+, potassium; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptors; NMDA R, N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; nNOS, neuronal NOS; PGE-2, prostaglandin E-2. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Autoregulation

Autoregulation is an active vascular process in the brain that acts to maintain adequate perfusion in the face of fluctuations in mean arterial pressure. Within the effective range of autoregulation (∼60–150 mmHg; Fig. 1), the tone of cerebral resistance arteries adjusts in response to variations in pressure, with pial and intraparenchymal vessels dilating to counteract reductions in mean arterial pressure and constricting in response to increases in pressure (58). Beyond the autoregulatory range, cerebral perfusion is unregulated and blood flow passively follows changes in pressure, resulting in potentially damaging levels of either hypo- or hyperperfusion in the brain. Cerebral autoregulation is believed to occur as a result of the intrinsic responses of vascular smooth muscle cells to changes in intravascular pressure (myogenic tone). Myogenic tone is mediated by increases in intracellular Ca2+ in response to ionic and enzymatic mechanisms, including the activation of stretch activated cation channels, including transient receptor potential channels, and other channels, leading to Ca2+ entry and subsequent increases in phosphorylation of myosin light chain promoting vasoconstriction (20).

Endothelial regulation

Cerebral endothelial cells play an important role in the maintenance and regulation of the vasculature in the brain and control the cerebral vascular tone by releasing vasorelaxant (e.g., NO, bradkykinin, and prostacyclin) and vasoconstrictive (e.g., endothelin) mediators (3). Under conditions of cardiovascular disease and ischemic stroke, these intrinsic properties of the cerebral vascular endothelium are impaired, resulting in impaired cerebral perfusion and an increased susceptibility to ischemic stroke (26). In addition to their role in cerebral perfusion, the tight interconnection between adjacent cerebral endothelial cells forms the primary structure of the blood–brain barrier (BBB)—the tight junction—which plays a key role in restricting the paracellular passage of molecules and ions between the blood and the brain (82). The integrity of the tight junction is maintained by complex interactions between tight junction proteins of adjacent endothelial cells. These include occludin, claudins, in particular, claudins-3, -5, and -12, and junctional adhesions molecules, which are tethered to the actin cytoskeleton by their interaction with accessory proteins, including members of the zona occludens family (1). Adherens junction proteins (e.g., vascular endothelial-cadherin) contribute to the maintenance of BBB integrity, however, these proteins are believed to play a more secondary role in tight junction stabilization. Following cerebral ischemia, breakdown of the BBB is pronounced and contributes to injury development (81) and this has been shown experimentally to be mediated by matrix metalloproteinase-induced degradation of tight junction proteins (6, 52, 80).

Influence of Hypertension and Diabetes on Cerebrovascular Regulation

Risk factors for ischemic stroke, including hypertension and diabetes mellitus, have profound effects on the cerebral circulation and impair the brain's intrinsic ability to safeguard against reductions in perfusion, altering both the structure and function of the cerebral vasculature (28, 39).

Structural alterations

Increased atherosclerotic plaque formation is observed throughout the circulation in patients with hypertension and diabetes (2, 11), contributing to an increased risk of thrombus formation, cerebral artery occlusion, and subsequent ischemic brain injury. In addition, hypertension and diabetes induce both endothelial dysfunction and opening of the BBB (37, 60, 72), which increase susceptibility to ischemic injury, as discussed above. Hypertension causes vascular hypertrophy and remodeling (both hypertrophic and eutrophic). Hypertrophic remodeling is characterized by a thickening of the vascular media, an increased size of vascular smooth muscle cells, and the accumulation of collagen, fibronectin, and elastin fragments, acting to increase the wall thickness and reduce the lumen diameter. In contrast, eutrophic remodeling leads to a reorganization of vascular smooth muscle cells, reducing the lumen diameter without changes in the wall thickness (10, 26, 33). Together, these structural alterations in the cerebral circulation reduce the patency and responsiveness of cerebral arteries and arterioles, increasing vascular resistance, compromising perfusion of the brain, and ultimately, increasing the susceptibility to ischemic stroke (26).

Autoregulation

In older hypertensive patients, a shift in the autoregulatory curve is observed such that higher pressures are required to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion (right-shift), while resting flow is also reduced (downward-shift) (75). In addition, the ability of cerebral vessels to dilate is impaired, failing to protect the brain from decreases in pressure (58). In a study of the retinal vasculature, which is both morphologically and functionally related to the cerebral circulation, patients with early essential hypertension had impaired endothelium-dependent maintenance of perfusion and vasodilation that could be reversed by blood pressure reduction with an angiotensin II subtype I receptor antagonist (23). Similarly, patients with chronic diabetes have impaired cerebral autoregulatory capacity. Long-term diabetics have been shown to have impaired autoregulation in response to increases and decreases in blood pressure, with cerebral blood flow passively following pressure (12, 36). Whereas the impairment of cerebral autoregulation in diabetic patients has been attributed to both microvascular disease and cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, autoregulatory dysfunction has been demonstrated in type 2 diabetes patients without clinical indications of microvascular disease and may suggest that autoregulatory dysfunction is an early sign of developing microvascular damage (47).

Functional hyperemia

Hypertension and diabetes disrupt the process of functional hyperemia in the brain. Individuals with untreated chronic hypertension have impaired cerebral blood flow responses following brain activation (43). In addition, experiments in rodents have shown that slowly developing hypertension in response to chronic treatment with subpressor doses of angiotensin II (Ang II), a model that reproduces select components of human hypertension (62), results in an impairment of functional hyperemia (45). Capone and colleagues demonstrated a key role for NADPH oxidase-derived free radicals in the development of this dysfunction (18, 32, 44) that appears to be regulated centrally by key cardiovascular circuits in the brain, including the subfornical organ (19). Interestingly, the impairment of functional hyperemia in response to Ang II infusion precedes significant elevations in blood pressure and ultimately recovers upon blood pressure normalization (18), suggesting that the effect of hypertension on vascular function is reversible in this model. In contrast, impairments in functional hyperemia observed in spontaneously hypertensive rats are not reversed by lowering blood pressure (17), indicating that in contrast to Ang II infusion, the dysfunction occurring in this model may be a result of a chronic structural alteration within the cerebrovasculature. The influence of diabetes on functional hyperemia in the cerebral circulation was recently addressed using rat models of both type I (streptozotocin-induced) (77) and type II (Goto-Kakizaki rat) (46) diabetes. Both studies reported impaired cerebral blood flow responses in the somatosensory cortex in response to either the sciatic nerve or whisker stimulation, consistent with an impairment of neurovascular coupling in the diabetic brain. However, as the influence of glucose normalization on impaired functional hyperemia was not assessed, it remains to be determined if the effects of diabetes on this process can be reversed by measures aimed at reducing blood glucose.

Influence of Ischemic Stroke on Cerebrovascular Regulation

Functional hyperemia

Animal studies

In rodents, functional hyperemia is impaired following ischemic stroke, with dysfunction occurring immediately upon induction ischemia and persisting for up to several days after the initial ischemic insult (Table 1). Early work by Busto and colleagues demonstrated delayed effects of focal ischemia on neurovascular function in the rat (30). They reported an impairment of functional hyperemia at a site remote from the location of the lesion up to 5 days after ischemia, with an attenuated increase in cerebral blood flow in response to functional stimulation. Interestingly, the increase in glucose consumption in response to stimulation was similarly attenuated in this region, as was the resting cerebral blood flow, raising the possibility that in this study, an overall depression of the brain function was occurring after stroke, as opposed to a selective disruption of functional hyperemia.

Table 1.

Effect of Focal or Global Ischemia on Functional Hyperemia: Animal Studies

| Ischemia model | Species | Ischemia duration | Quantification | Stimulus | Effects on functional hyperemia | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global ischemia (CCA/VA occlusion) | Rat | Transient (30 min) | Autoradiography (IAP, 2-DG) | Forepaw stimulation | Attenuated CBF | Ueki et al. (76) |

| Focal ischemia (photothrombotic) | Rat | Permanent | Autoradiography (IAP, 2-DG) | Whisker stimulation | Attenuated CBF | Ginsberg et al. (30) |

| Focal ischemia (MCA occlusion) | Rat | Permanent and transient (15 min) | fMRI (ASL) | Forepaw stimulation | Attenuated CBF (permanent) and no effect (transient) | Shen et al. (68) |

| Focal ischemia (MCA occlusion) | Mouse | Transient (30 min) | Laser Doppler flowmetry | Whisker stimulation | Attenuated CBF | Kunz et al. (49) |

| Global ischemia (CCA/SCA occlusion) | Rat | Permanent, increasing intensity | Laser speckle contrast imaging | Forepaw stimulation | Attenuated CBF | Baker et al. (8) |

2-DG, [14C]deoxyglucose; ASL, arterial spin labeling; CBF, cerebral blood flow; CCA, common carotid artery; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; IAP, [14C]iodoantipyrine; MCA, middle cerebral artery; SCA, subclavian artery; VA, vertebral artery.

Direct evidence of impaired functional hyperemia following experimental ischemia was provided by Hossman and colleagues (76). In rat, forepaw stimulation failed to increase cerebral blood in the region of the somatosensory cortex 3 days after induction of global ischemia, while the corresponding increase in neural activity was preserved. This suggests that global ischemia selectively impairs communication between the vasculature and neurons rather than causing generalized inhibition of neural activity. Similarly, in a study of the acute effect of global ischemia on functional hyperemia in rat, cerebral blood flow responses to forepaw stimulation were attenuated by up to 90% after ischemia, with the reduction in cerebral blood flow more pronounced than the corresponding decreases in neuronal oxygen consumption and electrical activity (8). Kunz et al. reported an acute impairment in functional hyperemia after transient focal ischemia in mice, revealing a greater than 50% reduction in the cerebral blood flow response to whisker stimulation just 1 h after induction of reperfusion (49). Taken together, these studies suggest that an impairment of functional hyperemia can be detected in both the acute and chronic phases after ischemia and that the responses are similar for both focal and global ischemic insults.

Interestingly, the influence of cerebral ischemia on functional hyperemia appears to be dependent on the intensity of the ischemic insult. Indeed, increases in cerebral blood flow following forepaw stimulation were abolished acutely after permanent focal ischemia, while functional hyperemia was preserved in response to less intense periods of subinjurious, brief ischemia (68). Consistent with this, stepwise increases in the severity of global ischemia resulted in a graded uncoupling of functional hyperemia in response to forepaw stimulation (8). Thus, the degree of impairment of functional hyperemia appears to be proportional to the severity of the ischemic insult. It is conceivable that this dysfunction in functional hyperemia contributes to the development of cerebral infarction, by impairing collateral perfusion and increasing infarct expansion into the ischemic penumbra. However, it is equally plausible that the impairment in functional hyperemia is secondary to the ischemic brain injury and therefore does not contribute to tissue damage.

Human studies

The influence of ischemic stroke on functional hyperemia is variable in humans, with select studies reporting both an attenuation and preservation of neurovascular coupling following cerebral ischemia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of Cerebral Ischemia on Functional Hyperemia: Human Studies

| Vascular pathology | Quantification | Stimulus | Timing of measurement | Effect on functional hyperemia | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIA, minor stroke (ICA territory) | PET | Motor | Chronic (>2 months) | Preserved | Inao et al. (42) |

| TIA, minor stroke, no symptom (ICA steno-occlusion) | PET | Visual | Chronic (7–30 days) | Preserved (visual cortex) and attenuated (surrounding ROIs) | Yamauchi et al. (79) |

| Subcortical infarct | fMRI BOLD | Sensory motor | Chronic (4–660 days) | Attenuated | Pineiro et al. (59) |

| Multiple vascular pathology and infarction | fMRI BOLD, ASL, and VASO-FLAIR | Motor | Chronic (9–57 months) | Attenuated (BOLD) and preserved (ASL, VASO-FLAIR) | Blicher et al. (13) |

| MCA stenosis and SVD with lacunar infarct | Transcranial Doppler (PCA) | Visual | Chronic (2–85 months) | Attenuated | Lin et al. (51) |

BOLD, blood oxygenation level dependent; ICA, internal carotid artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; PET, positron emission tomography; ROIs, regions of interest; SVD, small vessel disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VASO-FLAIR, vascular-space-occupancy fluid attenuated inversion recovery.

Inao et al. used positron emission tomography (PET) to assess functional hyperemia in patients with unilateral internal carotid artery (ICA)or MCA steno-occlusive lesions (42). Interestingly, functional hyperemia in response to bilateral motor activation was preserved in both the ipsilateral and contralateral primary somatosensory cortices, areas activated by the stimulus, whereas the increase in cerebral blood flow in response to a stimulus was attenuated in the surrounding regions. Similarly, cerebral blood flow changes in response to visual stimulation in patients with unilateral ICA stenosis and occlusions were preserved in the ipsilateral visual cortex, while the increase in cerebral blood flow in the surrounding regions was significantly decreased (79). Collectively, these studies indicate that after ischemic events, functional hyperemia may be preserved in brain regions with increased functional activation, possibly at the expense of surrounding tissue.

In contrast to studies using PET, the intensity and rate of increase of the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal in the sensorimotor cortex in response to hand movement was reduced bilaterally in patients with unilateral subcortical infarcts (59), indicating a global attenuation of functional hyperemia in the chronic phase after stroke. Similarly, wrist movement failed to increase the BOLD signal in the primary motor cortex in chronic stroke patients (13), suggesting impaired functional hyperemia in regions with increased functional activity. However, when cerebral blood flow and blood volume were assessed in response to functional activation using the more direct methods of arterial spin labeling (ASL) and vascular-space-occupancy-fluid attenuated inversion recovery, functional hyperemia was, in fact, maintained in the motor cortex after stroke (13). The reasons for the discrepancy between the results obtained with BOLD and ASL remain unclear. Beside differences related to the clinical picture, the BOLD signal is derived from the paramagnetic properties of deoxyhemoglobin and depends on cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic oxygen consumption, and cerebral blood volume (53). Thus, after stroke, such a relationship could be altered complicating the interpretation of changes in the BOLD signal. Impaired functional hyperemia after stroke has recently been reported using transcranial laser Doppler (51), yet, despite certain strengths of this technique, with time, it will likely be replaced by more sophisticated imaging technologies with higher spatial resolutions and the ability to quantify absolute flow, as detailed above.

Ultimately, understanding the influence of ischemia on functional hyperemia is of great importance if it can be harnessed clinically for diagnosis and prognostication in ischemic stroke patients. Although select studies do support a relationship between the efficiency of functional hyperemia and improved clinical outcome (16, 66), the majority of findings have been mixed, and there is therefore a clear need for future studies to incorporate more a controlled study design and patient populations.

Autoregulation

Animal studies

The influence of cerebral ischemia on autoregulation has been examined in the initial and delayed phases after focal and global ischemia–reperfusion (Table 3). Early work by Shiokawa et al. (70) examined the effect of transient forebrain ischemia on autoregulation in response to graded hypotension. Early (30 min) during the ischemic period, a reduction in mean arterial pressure of between 15% and 30% significantly reduced cerebral blood flow in the ischemic core, indicative of an acute impairment of the lower limit of autoregulation. Interestingly, the autoregulatory function did not recover acutely upon induction of reperfusion, suggesting the impairment of autoregulation to persist after ischemia despite recovery of flow. Dirnagl and Pulsinelli similarly reported early impairments in autoregulation during focal ischemia (24). Within the ischemic period, the autoregulatory function in response to induced hypotension and hypertension was completely abolished in the infarct core, with cerebral blood flow passively following arterial blood pressure. Interestingly, the slope of the passive relationship between cerebral blood flow and mean arterial pressure was also attenuated, suggesting that impaired vascular reactivity in this region may be contributing to the autoregulatory dysfunction. In addition, they reported autoregulation to be attenuated in tissue with a less severe reduction in blood flow, suggesting that autoregulatory impairment is not restricted to the ischemic core early after ischemia, but could also occur in peripheral regions.

Table 3.

Effect of Focal and Forebrain Ischemia on Autoregulation: Animal Studies

| Ischemia model | Species | Ischemia duration | Quantification | Timing of measurement | Effect on autoregulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focal ischemia (MCA/CCA occlusion) | Rat (SHR) | Permanent | Laser Doppler | Early (<60 min Isch) | Increasing impairment with increasing ischemia (UL and LL with vasoactive agents) | Dirnagl and Pulsinelli (24) |

| Forebrain ischemia (CCA occlusion) | Rat (SHR) | Transient (60 min) | Hydrogen clearance | Early (30 min Isch and 30 min Rep) | Impaired (LL with blood removal) | Shiokawa et al. (70) |

| Focal ischemia (endothelin-1 MCA occlusion) | Rat | Transient | Autoradiography (14C-IAP, 99mTc-HMPAO) | Delayed (24 h) | Not impaired (core) and impaired (peripheral regions) (LL with halothane) | MacGregor et al. (54) |

| Forebrain ischemia (CCA occlusion) with hypoxia | Rat | Transient (15 min) | Laser Doppler | Early (10 min Isch and <90 min Rep) | Impaired (spontaneous) | Roehl et al. (64) |

| Forebrain ischemia (↑intracranial pressure) with hypoxia | Piglet | Transient (10 min hypoxia and 20 min ischemia) | Arterial diameter measurement | Early (60 min) | Impaired (LL with blood removal) | Wang et al. (78) |

C-IAP, carbon 14-labeled iodoantipyrine; Isch, ischemia; LL, lower limit; min, minutes; Rep, reperfusion; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; 99mTc-HMPAO, technecium 99-labeled d,l-hexamethylproyleneamine oxide; UL, upper limit.

Autoregulation has been reported to be impaired 24 h after endothelin-1-induced cerebral ischemia, a time when cerebral infarction has developed. Autoregulation to induced hypotension was impaired in the peri-infarct tissue (54), suggesting a role for autoregulatory dysfunction in infarct expansion into the tissue of the ischemic penumbra during the chronic phase after stroke.

Two recent studies examined the influence of forebrain hypoxia ischemia on autoregulation in the cerebral circulation (64, 78). Acute impairments of autoregulation were reported within 60–90 min of reperfusion, suggesting a similar early disruption of cerebral autoregulation with this model of ischemia.

Human studies

There is a vast body of evidence supporting impaired cerebral autoregulation following ischemic stroke in humans (Table 4), which has been recently reviewed (5, 29, 48). Autoregulatory impairment is observed in both the acute and chronic phases after stroke, with both selective impairment of the affected hemisphere and more widespread, global deficits in cerebral autoregulation reported.

Table 4.

Effect of Cerebral Ischemia on Autoregulation: Human Studies

| Pathology | CBF quantification | Timing of measurement | Effect on autoregulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical and subcortical infarction | Transcranial Doppler (MCA) | Acute (within 48 h) | Impaired bilaterally (thigh cuff and spontaneous) | Saeed et al. (65) |

| MCA territory and lacunar infarction | Transcranial Doppler (MCA) | Acute (within 72 h) | Impaired bilaterally (lacunar) and unilaterally (MCA) (spontaneous) | Imminik et al. (41) |

| MCA territory infarction | Transcranial Doppler (MCA) | Acute (within 48 h) and chronic (5–7 days) | Impaired (spontaneous) | Reinhard et al. (63) |

| Lacunar and anterior circulation (partial and total) infarction | PET | Acute/chronic (1–11 days) | Not impaired (LL with nicardipine infusion) | Powers et al. (61) |

| MCA territory infarction | Transcranial Doppler (MCA) | Chronic (>6 months) | Impaired bilaterally (spontaneous) | Aoi et al. (4) |

| MCA territory infarction | Transcranial Doppler (MCA) | Chronic (0.5–30.9 years) | Impaired bilaterally (spontaneous) | Hu et al. (35) |

Saeed et al. evaluated autoregulation in acute ischemic stroke patients with cortical and subcortical infarctions in response to static (thigh cuff ) and spontaneous changes in blood pressure (65). They reported autoregulation to be impaired bilaterally within 48 h of stroke onset, consistent with a global hemispheric impairment of cerebral autoregulation in the acute phase after stroke. Consistent with this, a study of subjects with lacunar stroke, most likely caused by intracranial small vessel occlusion, reported a bilateral impairment of autoregulation, with cerebral blood flow passively following blood pressure in response to spontaneous elevations and reductions in pressure (41). However, in the same study, autoregulation was shown to be impaired selectively in the affected hemisphere in patients with more severe MCA territory strokes, in which occlusion could have been a result of either an embolus or a large cerebral artery thrombosis. Thus, it appears that the presence of either unilateral or bilateral hemispheric autoregulatory dysfunction in the acute phase after stroke is probably not dependent on the degree of ischemic brain injury, but rather a manifestation of the degree of underlying chronic small vessel disease due to stroke risk factors.

A recent study of patients with both minor and major strokes examined the progression of autoregulatory impairment in the transition from the acute to chronic phases (63). A bilateral deterioration in cerebral autoregulation was observed in the transition from the acute (<48 h) to chronic phase (5–7 days) after stroke, with an increased correlation between cerebral blood flow and spontaneous changes in blood pressure and a reduction in phase shift. Interestingly, during the chronic phase, a greater impairment of autoregulation was shown to correlate with an increased degree of cerebral infarction. Bilateral impairment in cerebral autoregulation has also been observed 6 months after stroke and has been shown to correlate with the degree of functional impairment (4, 35). One recent study failed to support impaired autoregulation between 1 and 11 days after stroke (61), however, since cerebral blood flow responses were only assessed in response to static hypotension and the study population was both small and highly heterogeneous, these findings will need to be validated by future studies.

Thus, although data generally support impaired cerebral autoregulation in ischemic stroke patients both in the acute and chronic phases, there appears to be a great deal of variability as to whether dysfunction is restricted to the affected hemisphere or occurs bilaterally. Such variability is likely due to a lack of standardization in the study design, in particular, the use of either static or dynamic blood pressure alterations, in addition to the heterogeneity of patient populations, particularly with regard to the degree of small vessel disease.

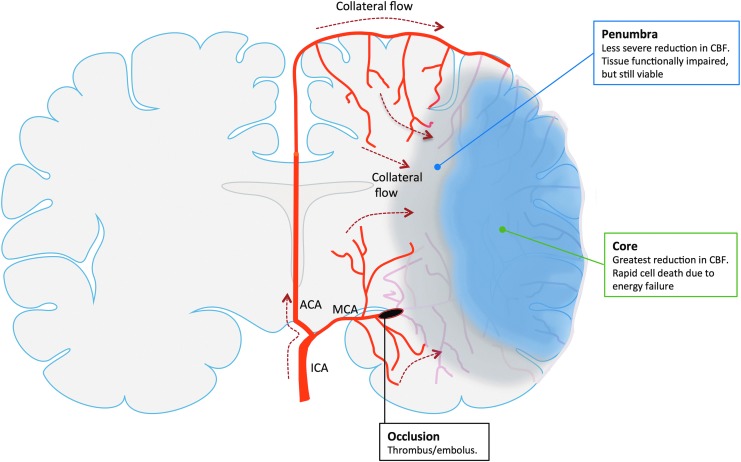

Contribution to Ischemic Brain Injury

After stroke, tissue of the ischemic core dies rapidly due to energetic and ionic failure, while the surrounding tissue, known as the ischemic penumbra, remains viable (55). Although the cellular function is impaired in penumbral tissue, activity can be recovered and incorporation into the ischemic lesion avoided, provided cerebral blood flow is restored (7). The fate of the ischemic penumbra is largely dependent on the efficiency of the collateral circulation (Fig. 3). This is present at the level of the pial and intraparenchymal vascular networks and plays a key role in the maintenance of perfusion following vascular occlusion. As discussed in the previous sections, cerebrovascular dysfunction occurring in response to risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, and after ischemic injury, manifests itself as a reduction in adequate perfusion of the areas of the brain at risk for infarction and this occurs as a result of insufficient collateral flow arising from adjacent, normally perfused territories. Indeed, the degree of collateralization has been shown to be a predictor of injury (9) and functional outcome (50) in stroke patients. Consequently, the methods aimed at enhancing collateral perfusion, possibly by inducing hypertension, may represent useful therapeutic strategies for the treatment of ischemic stroke (71).

FIG. 3.

Collateral perfusion in the brain after focal cerebral ischemia. After occlusion of a cerebral artery, like the MCA, the reduction in CBF is not homogenous throughout the ischemic territory. Rather, there is a central region (ischemic core) where the reduction in CBF is most severe resulting in rapid cell death due to lack of ATP and failure of ionic pumps (energy failure). In contrast, the area surrounding the core (ischemic penumbra) receives sufficient flow to remain vital, but has impaired functionality. The fate of the ischemic penumbra is largely dependent on the efficiency of the collateral circulation. Supplied by vessels from adjacent vascular territories unaffected by the vascular occlusion, collateral flow mitigates the CBF reduction in peripheral regions of the ischemic territory, which, if adequate, prevents recruitment of penumbral tissue into the ischemic core. ACA, anterior communicating artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Concluding Remarks

The brain has a number of intrinsic mechanisms for protecting against reductions in perfusion, which exist both at a structural (vascular architecture and topography) and functional (autoregulation, functional hyperemia, and endothelial regulation) level. Vascular risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, and acute ischemia impair these protective mechanisms, resulting in reduced collateral perfusion and increased susceptibility to focal ischemic injury. Gaining a better understanding of these processes may provide the opportunity to reduce ischemic injury by protecting vascular function during and after cerebral ischemia.

Abbreviations Used

- 14C-IAP

carbon 14-labeled iodoantipyrine

- 2-DG

[14C]deoxyglucose

- 99mTc-HMPAO

technecium 99-labeled d,l-hexamethylproyleneamine oxide

- ACA

anterior communicating artery

- Ado

adenosine

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ASL

arterial spin labeling

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- BOLD

blood oxygenation level dependent

- Ca2+

calcium

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CCA

common carotid artery

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- Glu

glutamate

- H+

hydrogen

- IAP

[14C]iodoantipyrine

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- Isch

ischemia

- K+

potassium

- LL

lower limit

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptors

- min

minutes

- NMDA R

NMDA receptors

- nNOS

neuronal NO synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- PCA

posterior cerebral artery

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PGE-2

prostaglandin E-2

- Rep

reperfusion

- ROI

regions of interest

- SCA

subclavian artery

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- SVD

small vessel disease

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

- TRP

transient receptor potential

- UL

upper limit

- VA

vertebral artery

- VASO-FLAIR

vascular-space-occupancy-fluid attenuated inversion recovery

References

- 1.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, Yusof SR, and Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 37: 13–25, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander RW. Theodore Cooper Memorial Lecture. Hypertension and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Oxidative stress and the mediation of arterial inflammatory response: a new perspective. Hypertension 25: 155–161, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andresen J, Shafi NI, and Bryan RM. Endothelial influences on cerebrovascular tone. J Appl Physiol 100: 318–327, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoi MC, Hu K, Lo M-T, Selim M, Olufsen MS, and Novak V. Impaired cerebral autoregulation is associated with brain atrophy and worse functional status in chronic ischemic stroke. PLoS One 7: e46794, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aries MJH, Elting JW, De Keyser J, Kremer BPH, and Vroomen PCAJ. Cerebral autoregulation in stroke: a review of transcranial Doppler studies. Stroke 41: 2697–2704, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, Sumii T, Jung JC, Moskowitz MA, Fini ME, and Lo EH. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 21: 7724–7732, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astrup J, Siesjo BK, and Symon L. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia - the ischemic penumbra. Stroke 12: 723–725, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker WB, Sun Z, Hiraki T, Putt ME, Durduran T, Reivich M, Yodh AG, and Greenberg JH. Neurovascular coupling varies with level of global cerebral ischemia in a rat model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33: 97–105, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bang OY, Saver JL, Buck BH, Alger JR, Starkman S, Ovbiagele B, Kim D, Jahan R, Duckwiler GR, Yoon SR, Viñuela F, and Liebeskind DS. UCLA Collateral Investigators. Impact of collateral flow on tissue fate in acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 79: 625–629, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumbach GL, and Heistad DD. Cerebral circulation in chronic arterial hypertension. Hypertension 12: 89–95, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckman JA, Creager MA, and Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA 287: 2570–2581, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentsen N, Larsen B, and Lassen NA. Chronically impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in long-term diabetics. Stroke 6: 497–502, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blicher JU, Stagg CJ, Shea JOA, Stergaard LO, MacIntosh BJ, Johansen-Berg H, Jezzard P, and Donahue MJ. Visualization of altered neurovascular coupling in chronic stroke patients using multimodal functional MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 2044–2054, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blinder P, Shih AY, Rafie C, and Kleinfeld D. Topological basis for the robust distribution of blood to rodent neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 12670–12675, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blinder P, Tsai PS, Kaufhold JP, Knutsen PM, Suhl H, and Kleinfeld D. The cortical angiome: an interconnected vascular network with noncolumnar patterns of blood flow. Nat Neurosci 16: 889–897, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buma FE, Lindeman E, Ramsey NF, and Kwakkel G. Functional neuroimaging studies of early upper limb recovery after stroke: a systematic review of the literature. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 24: 589–608, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calcinaghi N, Wyss MT, Jolivet R, Singh A, Keller AL, Winnik S, Fritschy JM, Buck A, Matter CM, and Weber B. Multimodal imaging in rats reveals impaired neurovascular coupling in sustained hypertension. Stroke 44: 1957–1964, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capone C, Faraco G, Park L, Cao X, Davisson RL, and Iadecola C. The cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by slow pressor doses of angiotensin II precedes the development of hypertension. Am J Physiol 300: H397–H407, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capone C, Faraco G, Peterson JR, Coleman C, Anrather J, Milner TA, Pickel VM, Davisson RL, and Iadecola C. Central cardiovascular circuits contribute to the neurovascular dysfunction in angiotensin II hypertension. J Neurosci 32: 4878–4886, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cipolla MJ. The Cerebral Circulation. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabertrand F, Hannah RM, Pearson JM, Hill-Eubanks DC, Brayden JE, and Nelson MT. Prostaglandin E2, a postulated astrocyte-derived neurovascular coupling agent, constricts rather than dilates parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33: 479–482, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del Zoppo GJ. and Hallenbeck JM. Advances in the vascular pathophysiology of ischemic stroke. Thromb Res 98: 73–81, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delles C, Michelson G, Harazny J, Oehmer S, Hilgers KF, and Schmieder RE. Impaired endothelial function of the retinal vasculature in hypertensive patients. Stroke 35: 1289–1293, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dirnagl U. and Pulsinelli W. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in experimental focal brain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10: 327–336, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drake CT. and Iadecola C. The role of neuronal signaling in controlling cerebral blood flow. Brain Lang 102: 141–152, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faraci FM. Protecting against vascular disease in brain. Am J Physiol 300: H1566–H1582, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faraci FM. and Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ Res 66: 8–17, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faraco G. and Iadecola C. Hypertension: a harbinger of stroke and dementia. Hypertension 62: 810–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giannopoulos S, Katsanos AH, Tsivgoulis G, and Marshall RS. Statins and cerebral hemodynamics. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 1973–1976, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginsberg MD, Castella Y, Dietrich WD, Watson BD, and Busto R. Acute thrombotic infarction suppresses metabolic activation of ipsilateral somatosensory cortex: evidence for functional diaschisis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 9: 329–341, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girouard H. and Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol 100: 328–335, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Girouard H, Park L, Anrather J, Zhou P, and Iadecola C. Cerebrovascular nitrosative stress mediates neurovascular and endothelial dysfunction induced by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 303–309, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Sachidanandam K, Johnson MH, Dorrance AM, Stepp DW, Fagan SC, and Ergul A. Type 2 diabetes causes remodeling of cerebrovasculature via differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagen synthesis: role of endothelin-1. Diabetes 54: 2638–2644, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirsch S, Reichold J, Schneider M, Székely G, and Weber B. Topology and hemodynamics of the cortical cerebrovascular system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32: 952–967, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu K, Lo M-T, Peng C-K, Liu Y, and Novak V. A nonlinear dynamic approach reveals a long-term stroke effect on cerebral blood flow regulation at multiple time scales. PLoS Comp Biol 8: e1002601, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu K, Peng CK, Huang NE, Wu Z, Lipsitz LA, Cavallerano J, and Novak V. Altered phase interactions between spontaneous blood pressure and flow fluctuations in type 2 diabetes mellitus: nonlinear assessment of cerebral autoregulation. Physica A 387: 2279–2292, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber JD. Diabetes, cognitive function, and the blood-brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des 14: 1594–1600, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 347–360, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iadecola C. and Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab 7: 476–484, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iadecola C. and Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci 10: 1369–1376, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Immink RV, van Montfrans GA, Stam J, Karemaker JM, Diamant M, and van Lieshout JJ. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation in acute lacunar and middle cerebral artery territory ischemic stroke. Stroke 36: 2595–2600, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inao S, Tadokoro M, Nishino M, Mizutani N, Terada K, Bundo M, Kuchiwaki H, and Yoshida J. Neural activation of the brain with hemodynamic insufficiency. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18: 960–967, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Ryan C, Price JC, Greer P, Sutton-Tyrrell K, van der Veen FM, and Meltzer CC. Reduced cerebral blood flow response and compensation among patients with untreated hypertension. Neurology 64: 1358–1365, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazama K, Anrather J, Zhou P, Girouard H, Frys K, Milner TA, and Iadecola C. Angiotensin II impairs neurovascular coupling in neocortex through NADPH oxidase-derived radicals. Circ Res 95: 1019–1026, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kazama K, Wang G, Frys K, Anrather J, and Iadecola C. Angiotensin II attenuates functional hyperemia in the mouse somatosensory cortex. Am J Physiol 285: H1890–H1899, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly-Cobbs AI, Prakash R, Coucha M, Knight RA, Li W, Ogbi SN, Johnson M, and Ergul A. Cerebral myogenic reactivity and blood flow in type 2 diabetic rats: role of peroxynitrite in hypoxia-mediated loss of myogenic tone. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut 342: 407–415, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim Y-S, Immink RV, Stok WJ, Karemaker JM, Secher NH, and van Lieshout JJ. Dynamic cerebral autoregulatory capacity is affected early in type 2 diabetes. Clin Sci 115: 255–262, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kunz A. and Iadecola C. Chapter 14 cerebral vascular dysregulation in the ischemic brain. Handb Clin Neurol 92: 283–305, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kunz A, Park L, Abe T, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Zhou P, and Iadecola C. Neurovascular protection by ischemic tolerance: role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci 27: 7083–7093, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lima FO, Furie KL, Silva GS, Lev MH, Camargo ECS, Singhal AB, Harris GJ, Halpern EF, Koroshetz WJ, Smith WS, Yoo AJ, and Nogueira RG. The pattern of leptomeningeal collaterals on CT angiography is a strong predictor of long-term functional outcome in stroke patients with large vessel intracranial occlusion. Stroke 41: 2316–2322, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin WH, Hao Q, Rosengarten B, Leung WH, and Wong KS. Impaired neurovascular coupling in ischaemic stroke patients with large or small vessel disease. Eur J Neurol 18: 731–736, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J, Jin X, Liu KJ, and Liu W. Matrix metalloproteinase-2-mediated occludin degradation and caveolin-1-mediated claudin-5 redistribution contribute to blood-brain barrier damage in early ischemic stroke stage. J Neurosci 32: 3044–3057, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Logothetis NK. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 453: 869–878, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacGregor DG, Carswell HV, Graham DI, McCulloch J, and Macrae IM. Impaired cerebral autoregulation 24 h after induction of transient unilateral focal ischaemia in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 12: 58–66, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, and Iadecola C. The science of stroke: mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron 67: 181–198, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen J, Nishimura N, Fetcho RN, Iadecola C, and Schaffer CB. Occlusion of cortical ascending venules causes blood flow decreases, reversals in flow direction, and vessel dilation in upstream capillaries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: 2243–2254, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishimura N, Rosidi NL, Iadecola C, and Schaffer CB. Limitations of collateral flow after occlusion of a single cortical penetrating arteriole. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 1914–1927, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, and Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 2: 161–192, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pineiro R. Altered hemodynamic responses in patients after subcortical stroke measured by functional MRI. Stroke 33: 103–109, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, and Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol 304: H1598–H1614, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powers WJ, Videen TO, Diringer MN, Aiyagari V, and Zazulia AR. Autoregulation after ischaemic stroke. J Hypertens 27: 2218–2222, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 37: 1199–1208, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reinhard M, Rutsch S, Lambeck J, Wihler C, Czosnyka M, Weiller C, and Hetzel A. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation associates with infarct size and outcome after ischemic stroke. Acta Neurol Scand 125: 156–162, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roehl AB, Zoremba N, Kipp M, Schiefer J, Goetzenich A, Bleilevens C, Kuehn-Velten N, Tolba R, Rossaint R, and Hein M. The effects of levosimendan on brain metabolism during initial recovery from global transient ischaemia/hypoxia. BMC Neurol 12: 81, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saeed NP, Panerai RB, Horsfield MA, and Robinson TG. Does stroke subtype and measurement technique influence estimation of cerebral autoregulation in acute ischaemic stroke? Cerebrovasc Dis 35: 257–261, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salinet ASM, Haunton VJ, Panerai RB, and Robinson TG. A systematic review of cerebral hemodynamic responses to neural activation following stroke. J Neurol 260: 2715–2721, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Nishimura N, Schroeder LF, Tsai PS, Ebner FF, Lyden PD, and Kleinfeld D. Two-photon imaging of cortical surface microvessels reveals a robust redistribution in blood flow after vascular occlusion. PLoS Biol 4: e22, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen Q, Ren H, Cheng H, Fisher M, and Duong TQ. Functional, perfusion and diffusion MRI of acute focal ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 25: 1265–1279, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shih AY, Blinder P, Tsai PS, Friedman B, Stanley G, Lyden PD, and Kleinfeld D. The smallest stroke: occlusion of one penetrating vessel leads to infarction and a cognitive deficit. Nat Neurosci 16: 55–63, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shiokawa O, Sadoshima S, Kusuda K, Nishimura Y, Ibayashi S, and Fujishima M. Cerebral and cerebellar blood flow autoregulations in acutely induced cerebral ischemia in spontaneously hypertensive rats—transtentorial remote effect. Stroke 17: 1309–1313, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shuaib A, Butcher K, Mohammad AA, Saqqur M, and Liebeskind DS. Collateral blood vessels in acute ischaemic stroke: a potential therapeutic target. Lancet Neurol 10: 909–921, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Starr JM, Wardlaw J, Ferguson K, MacLullich A, Deary IJ, and Marshall I. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability in type II diabetes demonstrated by gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74: 70–76, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takano T, Tian G-F, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, and Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci 9: 260–267, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takata N, Nagai T, Ozawa K, Oe Y, Mikoshiba K, and Hirase H. Cerebral blood flow modulation by basal forebrain or whisker stimulation can occur independently of large cytosolic Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes. PLoS One 8: e66525, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tryambake D, He J, Firbank MJ, O'Brien JT, Blamire AM, and Ford GA. Intensive blood pressure lowering increases cerebral blood flow in older subjects with hypertension. Hypertension 61: 1309–1315, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ueki M, Linn F, and Hossmann KA. Functional activation of cerebral blood flow and metabolism before and after global ischemia of rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 8: 486–494, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vetri F, Xu H, Paisansathan C, and Pelligrino DA. Impairment of neurovascular coupling in type 1 diabetes mellitus in rats is linked to PKC modulation of BK(Ca) and Kir channels. Am J Physiol 302: H1274–H1284, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Z, Ma N, Riley J, Armstead WM, and Liu R. Salvinorin A administration after global cerebral hypoxia/ischemia preserves cerebrovascular autoregulation via kappa opioid receptor in piglets. PLoS One 7: e41724, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yamauchi H, Kudoh T, Sugimoto K, Takahashi M, Kishibe Y, and Okazawa H. Altered patterns of blood flow response during visual stimulation in carotid artery occlusive disease. NeuroImage 25: 554–560, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang Y, Estrada EY, Thompson JF, Liu W, and Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinase-mediated disruption of tight junction proteins in cerebral vessels is reversed by synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in focal ischemia in rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 697–709, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang Y. and Rosenberg GA. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in acute and chronic cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 42: 3323–3328, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zlokovic BV. The blood-brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron 57: 178–201, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann K-A, Pozzan T, and Carmignoto G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci 6: 43–50, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]