Abstract

IL-17-induced joint inflammation is associated with increased angiogenesis. However, the mechanism by which IL-17 mediates angiogenesis is undefined. Therefore, the pathologic role of CXCL1 and CXCL5 was investigated in arthritis mediated by local expression of IL-17, employing a neutralizing antibody to each chemokine. Next, endothelial chemotaxis was utilized to examine whether endothelial migration was differentially mediated by CXCL1 and CXCL5. Our results demonstrate that IL-17-mediated disease activity was not affected by anti-CXCL1 treatment alone. In contrast, mice receiving anti-CXCL5 demonstrated significantly reduced clinical signs of arthritis, compared to the mice treated with IgG control. Consistently, while inflammation, synovial lining thickness, bone erosion and vascularization were markedly reduced in both the anti-CXCL5 and combination anti-CXCL1 and 5 treatment groups, mice receiving anti-CXCL1 antibody had clinical scores similar to the control group. In contrast to joint FGF2 and VEGF levels, TNF-α was significantly reduced in mice receiving anti-CXCL5 or combination of anti-CXCL1 and 5 therapies compared to the control group. We found that, like IL-17, CXCL1-induced endothelial migration is mediated through activation of PI3K. In contrast, activation of NF-κB pathway was essential for endothelial chemotaxis induced by CXCL5. Although CXCL1 and CXCL5 can differentially mediate endothelial trafficking, blockade of CXCR2 can inhibit endothelial chemotaxis mediated by either of these chemokines. These results suggest that blockade of CXCL5 can modulate IL-17-induced inflammation in part by reducing joint blood vessel formation through a non-overlapping IL-17 mechanism.

Keywords: IL-17-induced arthritis, CXCL1, CXCL5, Angiogenesis

Introduction

RA is an autoimmune disease in which angiogenesis can promote ingress of leukocytes, as well as pannus formation, thereby perpetuating inflammation and bone destruction [1]. Although RA was initially considered to be a TH-1-mediated disease, recent studies from experimental arthritis models indicate that TH-17 cells play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of the disease [2-5]. As such, the incidence and severity of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) were significantly alleviated in IL-17-deficient mice, and post-onset blockade of IL-17 ameliorates CIA inflammation and joint destruction [6]. Further, local expression of IL-17 exacerbates disease in the CIA [4] and K/BxN serum transfer arthritis models [3]. Not only can IL-17 amplify disease severity in experimental arthritis models, but its local expression can also mediate joint inflammation and synovial lining thickness in naive mice [3].

It has been shown that the proinflammatory activity of IL-17 is imparted by its ability to induce neutrophil ingression and granulopoiesis [7-9]. In studies using human neutrophils, migration induced by IL-17 was inhibited by a neutralizing antibody to IL-8, suggesting that IL-17-induced neutrophil migration is mediated through IL-8 production [10].

Previous studies have shown that IL-17-activated RA synovial tissue fibroblasts produce a number of CXC chemokines [11, 12] that are known to be neutrophil chemoattractant and proangiogenic. Further CXCL1 and CXCL5 mRNA transcripts are modulated by IL-17 through enhanced stabilization [12-14]. Chemokines such as CXCL1, 2, 3, 5 and 6, are corresponding ligands to CXCR2, and are important proangiogenic factors in RA joints [15-17] that can activate Matrigel tube formation and angiogenesis [18, 19]. Although blockade of CXCR1/CXCR2 in experimental arthritis models ameliorates joint inflammation by inhibiting adhesion and migration of neutrophils, the efficacy and the mechanism of the corresponding ligands are undefined [20-22].

Our recent studies demonstrate that IL-17 contributes to angiogenesis in RA since neutralization of IL-17 in RA synovial fluid or IL-17 receptor C (RC) on human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) significantly reduces RA synovial fluid induced endothelial migration [23]. We also show that vascularity was increased in an IL-17-induced arthritis model [23].

In the current study, we examined the hypothesis that IL-17-mediated arthritis may be due to elevated chemokine levels that promote angiogenesis. To find these important factors, we screened IL-17-activated macrophages, RA synovial tissue fibroblasts and HMVECs for proangiogenic chemokine expression. Elevated proangiogenic chemokine expression was validated in the IL-17-induced arthritis model. Although expression of several factors was identified in these cell types/tissues, CXCL1 and CXCL5 were the most highly expressed in IL-17-activated RA synovial tissue explants and the experimental arthritis model. To demonstrate the pathologic role of CXCL1 and CXCL5 in IL-17-mediated arthritis, neutralizing antibodies to each chemokine were employed. We found that arthritis severity and vascularization were significantly reduced in the anti-CXCL5 treatment group. In contrast, anti-CXCL1 treatment had no effect on IL-17-mediated disease activity or neovascularization, while being capable of inhibiting CXCL1-mediated endothelial chemotaxis in vitro. The combination of anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 was not more effective than anti-CXCL5 treatment alone. We next demonstrated that ligation to CXCR2 facilitates CXCL1 and CXCL5-induced endothelial migration although down stream signaling pathways are differentially regulated by these chemokines. We show that while CXCL1 can induce endothelial migration through activation of PI3K pathway, this process was mediated by CXCL5 through NF-κB signaling. Since both CXCL1 and IL-17 can mediate angiogenesis through the same pathway, blocking of CXCL1 is ineffective in this process whereas suppression of CXCL5 can effectively reduce NF-κB mediated angio-genesis. In conclusion, these observations suggest that IL-17-mediated joint vascularization may be in part due to CXCL5 induction.

Materials and methods

Cell and tissue treatment for mRNA studies

The studies were approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board and all donors gave informed written consent. Since the RA synovial tissues were recruited from the practices of orthopedic surgeons these samples are de-identified and therefore the disease severity and the treatment information is unavailable. RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were isolated from fresh RA synovial tissues, who fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA [24], by mincing and digesting in a solution of dispase, collagenase, and DNase [25-27]. Cells were used between passages 3–9. RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were treated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) from 0 to 8 h for mRNA studies. Also, RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were either untreated or treated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml), TNF-α (10 ng/ml) or IL-17 plus TNF-α for 8 h. Monocytes were separated from buffy coats (Lifesource, Chicago, IL) obtained from healthy donors [26, 28]. Mononuclear cells, isolated by Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) gradient centrifugation, were separated by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation. Monocytes were allowed to differentiate to macrophages as previously described [26, 28]. Macrophages were treated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) from 0 to 8 h for mRNA studies. To determine IL-17-induced proangiogenic factors in RA synovial tissue, RA synovial tissue explants were activated with IL-17 (100 ng/ml) or PBS for 24 h. Thereafter, tissues were harvested and homogenized and protein levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2 and VEGF were determined by ELISA and results were shown as fold increase above RA synovial tissue explants treated with PBS. To define which signaling pathways mediate IL-17-induced CXCL1 or CXCL5 secretion, macrophages or RA fibroblasts were either untreated or incubated with DMSO or inhibitors to PI3K (LY294002; 10 μM), ERK (PD98059; 10 μM), JNK (SP600125; 10 μM) or p38 (SB203580; 10 μM) for 1 h in serum free RPMI. Cells treated with DMSO or inhibitors were subsequently activated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) for 24 h and the media was collected in order to quantify the levels of CXCL1 or CXCL5 employing ELISA.

Real-time RT-PCR

Macrophages and RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were treated as mentioned in the figure legends and total cellular RNA was extracted using trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Subsequently, reverse transcription and real-time RT-PCR was performed as previously described [23, 28, 29]. Relative gene expression was determined by the ΔΔCt method normalized to GAPDH values, and results were shown as fold increase above 0 h and/or PBS treatment.

Tissue homogenization

Mouse ankles were homogenized as described previously [29, 30] in 1 ml of Complete Mini protease-inhibitor cocktail homogenization buffer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) on ice, followed by sonication for 30 s. Homogenates were centrifuged and filtered through a 0.45 μm pore size filter before quantifying the levels of various cytokines and chemokines by ELISA.

Cytokine quantification

Mouse CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2, VEGF, IL-1β, CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CCL20, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) ELISA kits were used according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

In vivo study protocol

The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed to determine the joint expression levels of CXCL1 and CXCL5 in an IL-17-induced arthritis model. For this purpose, 6-7-week-old C57BL/6 mice were injected intra-articularly with 107 PFU adenoviral (Ad)-IL-17 or Ad-control [23, 27]. Ankles were harvested on days 4 and 10 post-Ad-IL-17 or Ad-control injection, and joint CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2 (day 10) and VEGF (day 10) levels were quantified by ELISA. In a different set of studies, experiments were performed to determine whether CXCL1 and/or CXCL5 play a role in arthritis mediated by local IL-17 expression in mouse ankle joints. For this purpose, 6-7-week-old C57BL/6 mice were treated intraperitoneally with 30 μg (total of 210 μg was utilized in the course of treatment) of either IgG, monoclonal rat anti-mouse CXCL1, monoclonal rat anti-mouse CXCL5 or both anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 antibodies (at the concentrations of 1–2.5 μg/ml, anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 are capable of neutralizing 50% (ND50) of mouse CXCL1 and CXCL5 (at 30 ng/ml); Leinco Technologies, St. Louis, Missouri) on days −4, −2, 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 post-Ad injection with each group containing 10–12 mice. On day 0, Ad-IL-17 (107 PFU) was injected intra-articularly into the mouse ankle joints in each treatment group. Joint circumferences were measured on days 0, 3, 5, 7 and 10 post-Ad-IL-17 injection. On day 11, post-injection ankles were harvested for ELISA and immunohistochemical studies, and blood was collected by cardiac puncture to measure blood cell count using a HemaVet 850 complete blood counter (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT).

Clinical assessments

Ankle circumferences were determined by measurement of two perpendicular diameters, the latero-lateral diameter and the antero-posterior diameter, using a caliper (Lange Caliper; Cambridge Scientific Industries). Circumference was determined using the following formula: circumference = 2π × (sqrt(a2 + b2/2)) [31, 32].

Abs and immunohistochemistry

Mouse ankles were decalcified with ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 10% formalin for 3 weeks, formalin fixed and paraffin embedded, and sectioned in the pathology core facility. Inflammation, synovial lining and bone erosion (based on a 0–5 score) [33] were determined using H&E-stained sections by a blinded observer (A.M.M.). Mouse ankles were immunoperoxidase-stained using Vector Elite ABC Kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) as a chromogen by the pathology core facility. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized in xylene for 15 min at room temperature, followed by rehydration by transfer through graded alcohols. Antigens were unmasked by incubating slides in Proteinase K digestion buffer (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation with 3% H2O2 for 5 min. Nonspecific binding of avidin and biotin was blocked using an avidin/biotin blocking kit (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Nonspecific binding of antibodies to the tissues was blocked by pretreatment of tissues with Protein block (Dako). Tissues were incubated with Von willebrand factor (1:1,000 dilution; Dako) or control IgG antibody (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and treated with lithium carbonate for bluing. Endothelial staining was scored on a 0–5 scale where 0 = no staining, 1 = few cells stained, 2 = some (less than half) cells stained, 3 = around half of the cells were stained positively 4 = majority or more than half of the cells were positively stained, and 5 = all cells were positively stained. Data were pooled, the mean ± SEM was calculated and each slide was evaluated by a blinded observer (A.M.M.) [31, 32, 34, 35].

Characterization of CXCL1 and CXCL5 activated signaling pathways in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs)

HMVECs (passage 3–8) (Lonza, Walkersville, Maryland) were grown to 80% confluence in EGM-2 MV bullet kit (Lonza) and were incubated in endothelial basal medium (EBM) (Lonza) with 0% FBS for 2 h prior to treatment. Cells were then untreated or treated with CXCL1 or CXCL5 (20 ng/ml) for 5–65 min. Cell lysates were examined by Western blot analysis, as previously described [25, 26, 28]. Blots were probed with IKB, phospho (p)-p38, pAKT and pERK (Cell Signaling; 1:1,000 dilution) over-night or probed with actin, p38, AKT or ERK (Sigma or Cell Signaling; 1:3,000 dilution) for 1 h.

Examining the mechanism of CXCL1 and CXCL5-induced HMVEC migration

To examine chemotaxis, HMVECs were incubated in EBM (Lonza) with 0% FBS and no growth factors for 2 h before use. HMVECs (2.7 × 104 cells/25 μl EBM with 0.1% FBS) from different treatments were then placed in the bottom wells of a 48-well Boyden chemotaxis chamber (NeuroProbe, Cabin John, MD) with gelatin-coated polycarbonate membranes (8 μm pore size; Nucleopore, Pleasant, CA) [23, 36]. To define which signaling pathway(s) mediated CXCL1 and CXCL5-induced HMVEC chemotaxis, HMVECs were incubated with DMSO or inhibitors to PI3K (LY294002; 1 and 5 μM), ERK (PD98059; 1 and 5 μM), p38 (SB203580; 1 and 5 μM) or NF-κB (MG-132; 1 and 5 μM) at 37°C for 2 h, allowing endothelial cell attachment to the membrane [23]. The chamber was reinverted, and PBS, positive control VEGF (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems), CXCL1 (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems) or CXCL5 (20 ng/ml; R&D Systems) was added to the upper wells, and the chamber was further incubated for 2 h at 37°C. To examine whether CXCR2 is involved in CXCL1 and CXCL5-mediated HMVEC migration, HMVECs were incubated with antibody to CXCR2 (10 μg/ml, R&D systems; at 37°C for 2 h while cells were attaching to the membrane) and chemotaxis was examined in response to CXCL1 or CXCL5 (1 and 20 ng/ml; for 2 h at 37°C). Readings represent fold increase chemotaxis above cells migrating in response to PBS (cells were read in three high power × 40 fields/well, averaged for each triplicate wells and subsequent values are shown as fold increase above PBS values from two different chemotaxis assays).

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed employing 1-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc two-tailed Student’s t tests for paired and unpaired samples. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

IL-17 induces the expression of CXCL1 and CXCL5 from cells present in the RA joint through activation of PI3K and/or ERK pathway and IL-17 synergizes with TNF-α in inducing the expression of CXCL1 and CXCL5 in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts

IL-17-induced downstream targets were determined employing RA synovial tissue fibroblasts, macrophages differentiated in vitro from monocytes and endothelial cells, because these cells are important in the pathogenesis of RA. We found that RA synovial tissue fibroblasts and peripheral blood differentiated macrophages that are activated with IL-17 express higher levels of CXCL1 and CXCL5 (P < 0.05) starting at 4 h or 6 h post-stimulation (Figs. 1a, 1d, 2a, 2d), compared to control treatment. Further, only the expression of CXCL1 was significantly upregulated in HMVECs activated by IL-17 as early as 2 h post-stimulation, compared to controls (data not shown). Our previous studies demonstrate that in macrophages and RA synovial tissue fibroblasts IL-17 signals through ERK, p38 and AKT while it only activates JNK pathway in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts [27]. To determine the mechanism by which IL-17 induces CXCL1 and CXCL5 production, these pathways were suppressed in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts and macrophages activated by IL-17. Our data demonstrate that inhibition of PI3K and ERK pathways suppress production of CXCL1 in macrophages and CXCL5 in both cell types (Figs. 1e, 2c, 2e). However, in RA fibroblasts only inhibition of PI3K was capable of reducing IL-17-mediated CXCL1 levels (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

IL-17 induces production of CXCL1 in RA synovial fibroblasts and macrophages however, only in RA fibroblasts is CXCL1 expression synergistically induced by IL-17 and TNF-α. RA synovial tissue fibroblasts (a) and normal macrophages (d) were activated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) for 0–8 h. Real-time RT-PCR was employed to identify CXCL1 (a and d) mRNA levels which were normalized to GAPDH. The results are presented as fold increase, compared with the 0 h time point (untreated cells). RA synovial tissue fibroblasts (c) and normal macrophages (e) were either untreated or incubated with DMSO or inhibitors to PI3K (LY294002; 10 μM), ERK (PD98059; 10 μM), JNK (SP600125; 10 μM) or p38 (SB203580; 10 μM) for 1 h. Thereafter cells treated with DMSO or inhibitors were subsequently activated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) for 24 h and the media was collected from all conditions in order to quantify the levels of CXCL1 employing ELISA. b RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were either unstimulated or stimulated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml), TNF-α (10 ng/ml), or IL-17 plus TNF-α for 6 h. Cells were harvested, and CXCL1 mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR which were normalized to GAPDH and presented as fold increase above PBS treatment (unstimulated cells). Values represent the mean ± SE. * Represents P < 0.05 and ** denotes P < 0.01, n = 3–5

Fig. 2.

In RA synovial fibroblasts and macrophages, IL-17 induces production of CXCL5 however only in RA fibroblasts is CXCL5 expression synergistically induced by IL-17 and TNF-α stimulation. RA synovial tissue fibroblasts (a) and normal macrophages (d) were activated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) for 0–8 h. Real-time RT-PCR was employed to identify CXCL5 (a and d) mRNA levels which were normalized to GAPDH. The results are presented as fold increase, compared with the 0 h time point (untreated cells). RA synovial tissue fibroblasts (c) and normal macrophages (e) were either untreated or incubated with DMSO or inhibitors to PI3K (LY294002; 10 μM), ERK (PD98059; 10 μM), JNK (SP600125; 10 μM) or p38 (SB203580; 10 μM) for 1 h. Thereafter cells treated with DMSO or inhibitors were subsequently activated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml) for 24 h and the supernatants were collected from all conditions in order to quantify the levels of CXCL5 by ELISA. b RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were either unstimulated or stimulated with IL-17 (50 ng/ml), TNF-α (10 ng/ml), or IL-17 plus TNF-α for 6 h. Cells were harvested and CXCL5 mRNA levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR which were normalized to GAPDH and presented as fold increase above PBS treatment (unstimulated cells). Values represent the mean ± SE. * Represents P < 0.05 and ** denotes P < 0.01, n = 3–5

Interestingly, RA synovial tissue fibroblasts activated with IL-17 and TNF-α demonstrate significantly greater levels of CXCL1 (Fig. 1b) and CXCL5 (Fig. 2b), compared to cells activated with IL-17 or TNF-α alone. However, this synergistic effect was not detected in macrophages or when RA synovial tissue fibroblasts were stimulated with IL-17 and IL-1β (data not shown). Our results suggest that CXCL1 and CXCL5 may be important downstream mediators expressed by RA synovial cells in response to IL-17 stimulation, and that TNF-α stimulation further promotes IL-17 induction of these chemokines.

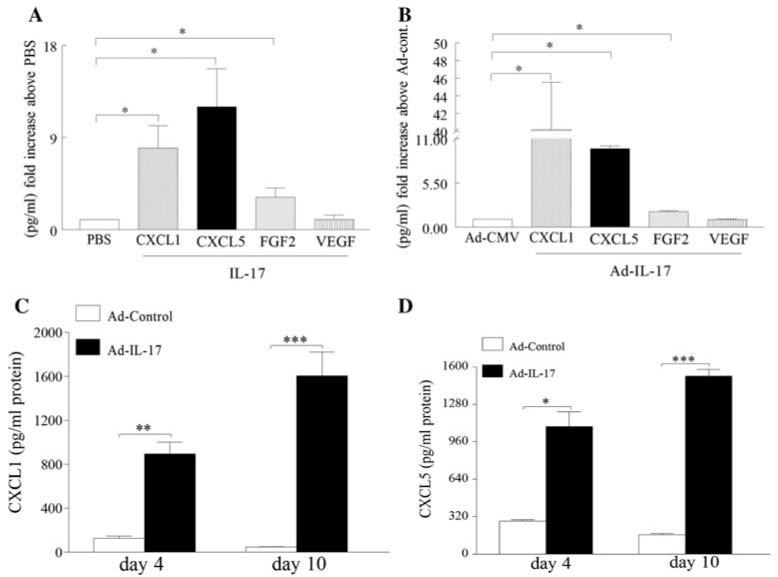

CXCL1 and CXCL5 are elevated in RA synovial tissue explants and IL-17-induced arthritis model

In order to determine the IL-17 modulated proangiogenic factors in RA synovial tissue explants and IL-17-induced arthritis model, levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2 and VEGF were quantified in IL-17 activated RA synovial tissue explants and/or IL-17-mediated arthritis ankles (harvested from day 10 post injection) and the data were demonstrated as fold increase above the control group (Fig. 3a, b). The results obtained from IL-17-induced arthritis model are similar to our finding in RA synovial tissue explants in that CXCL1 and CXCL5 are induced to a greater extent (40–10 fold increase in IL-17-induced arthritis ankles and 7–12 fold increase in RA explants compared to the control group) compared to FGF2 (3–2 fold increase respectively), while VEGF was not significantly elevated in any of the mentioned models. Although in the IL-17-induced arthritis model the relative increase levels above Ad-control is greater for CXCL1 (40 fold) compared to CXCL5 (tenfold) the absolute joint concentrations for CXCL1 (1,600 pg/ml) and CXCL5 (1,520 pg/ml) are comparable in day 10 post injection (Fig. 3c, d). Based on these results we concluded that CXCL1 and CXCL5 may be important in IL-17 mediated pathogenesis in RA and this experimental arthritis model.

Fig. 3.

IL-17 increases the expression of CXCL1 and CXCL5 in RA synovial tissue explants and experimental arthritis model. a RA synovial tissue explants were treated with PBS or IL-17 (100 ng/ml), tissues were harvested after 24 h and levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2 and VEGF were quantified by ELISA and normalized to PBS values. b Ad-IL-17 or Ad-CMV control (107 PFU) was injected intra-articularly into C57/BL6 mice. Ankles were harvested on day 10 and levels of CXCL1, CXCL5, FGF2 and VEGF were measured by ELISA and normalized to Ad-CMV. c, d Ankles from Ad-IL-17 and Ad-CMV treatment were harvested on days 4 and 10, and CXCL1 (c) and CXCL5 (d) levels were quantified by ELISA. Values are reported as mean ± SE. * Denotes P < 0.05, ** denotes P < 0.01 and *** denotes P < 0.005, n = 8–10

Inhibition of CXCL5 but not CXCL1 ameliorates IL-17-induced arthritis

Experiments were performed to determine whether CXCL1 and/or CXCL5 play a role in arthritis mediated by local IL-17 expression in mice ankle joints. In mice locally injected with IL-17 (and IgG control), disease activity determined by ankle circumference began around day 3 and progressed through day 5, plateauing thereafter until the termination of the experiments on day 10 (Fig. 4a). The disease activity determined by ankle circumference was significantly lower in mice receiving anti-CXCL1 on days 3 and 5, compared to the control group. However, as the arthritis progressed there was no difference noted at later time points (days 7 and 10) (Fig. 4a). In vitro chemotaxis performed on endothelial cells demonstrated that the anti-CXCL1 antibody could markedly suppress CXCL1-induced endothelial migration while anti-CXCL5 antibody did not have any effect on this process (data not shown). Further, mice receiving anti-CXCL5 demonstrated significantly reduced clinical signs of arthritis at all time points, compared to the mice treated with IgG control (P < 0.05). The combination of anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 did not ameliorate IL-17-induced joint inflammation beyond the effect observed using anti-CXCL5 alone. Next, histological examination of the joints was performed to determine the effect of treatment on inflammation, synovial lining and joint destruction. Consistent with the clinical data, histological analysis of the treatment groups demonstrated that inflammation, synovial lining thickening, and bone erosion were markedly reduced in the anti-CXCL5 and anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 treatment groups. In contrast, mice receiving anti-CXCL1 antibody had similar clinical scores compared to the control group (Fig. 4b, c). Our results demonstrate that CXCL5, and not CXCL1, plays an important role in IL-17-mediated arthritis.

Fig. 4.

Neutralization of CXCL5 ameliorates IL-17-induced joint inflammation, synovial lining thickness, bone erosion and joint TNF-α levels. C57BL/6 mice were treated intraperitoneally with 30 μg (total of 210 μg was utilized over the course of treatment) IgG, anti-CXCL1, anti-CXCL5 or both anti-CXCL1 and 5 antibodies (Leinco Technologies) on days −4, −2, 0, 3, 5, 7 and 9 post-Ad injection. On day 0, Ad-IL-17 (107 PFU) was injected intra-articularly into the mouse ankle joint, and the joint circumference (a) was measured on days 0, 3, 5, 7 and 10 post-Ad-IL-17 injection and each experimental group consisted of 10–12 mice. b, c Inflammation, synovial lining and bone erosion (based on a 0–5 score) were determined using H&Estained sections by a blinded observer, n = 10 ankles. Changes in the levels of joint TNF-α (d) were measured in ankle homogenates obtained from different treatment groups by ELISA and were normalized by protein concentration, n = 7–9 ankles. Values demonstrate mean ± SE. * Denotes P < 0.05

Anti-CXCL5 treatment downregulates proinflammatory mediators in IL-17-induced arthritis model

To determine the role of CXCL1 and CXCL5 on IL-17-induced arthritis, proinflammatory mediators were quantified in ankle joints. For this purpose, the effect of therapy was examined on joint TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL2, FGF2 and VEGF protein levels. Our results demonstrate that mice receiving anti-CXCL5 or combination therapy had 40–50% lower levels of joint TNF-α, compared to the control group (Fig. 4d). Joint CCL5 levels were also significantly (40–50%) reduced in IL-17-induced arthritis ankles receiving anti-CXCL5 or combination of anti-CXCL1 and 5, respectively (data not shown). Other joint proinflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-1β, CCL2, CCL3, CCL20, and CXCL2 were not affected by anti-CXCL5, anti-CXCL1 or combination treatments (data not shown). To demonstrate that the efficacy of anti-CXCL5 treatment is independent of the reduction of potent proangiogenic factors, joint FGF2 and VEGF were quantified in all four treatment groups. The data demonstrate that although levels of FGF2 but not VEGF are elevated in IL-17-induced arthritis model, ankles treated with anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL5 have similar levels of FGF2 (Fig. 5a) and VEGF (Fig. 5b) suggesting that anti-CXCL5 treatment can directly suppress IL-17-mediated angiogenesis. These results demonstrate that neutralization of CXCL5 modulates joint TNF-α and CCL5 levels in IL-17-mediated arthritis model.

Fig. 5.

Levels of joint FGF2 and VEGF were unaffected by anti-CXCL5 and combination therapy and anti-CXCL5 therapy downregulates IL-17-induced joint vascularization. Changes in the levels of joint FGF2 (a) and VEGF (b) were measured in ankle homogenates obtained from different treatment groups by ELISA and the data is presented as fold increase above the control IgG treatment, n = 7–9 ankles. IL-17-induced arthritis ankles treated with IgG, anti-CXCL1, anti-CXCL5 or the combination therapy were harvested on day 11 and were immunostained with Von willebrand factor (endothelial marker) (c) (original magnification × 200). Quantification of endothelial (d) staining from IL-17-induced arthritis ankles harvested on day 11, n = 8–9 ankles. Values demonstrate mean ± SE. * Denotes P < 0.05

Anti-CXCL5 treatment reduces IL-17-induced vascularization

To determine the mechanism by which anti-CXCL5 ameliorates IL-17-induced arthritis, ankles were examined for joint vascularization. The data demonstrate that while levels of vascularization were similar in the IgG and the anti-CXCL1 treatment groups, anti-CXCL5 and the combination therapy had 40% fewer blood vessels (Fig. 5c, d). Our results may suggest that neutralization of CXCL5 can affect IL-17-induced arthritis through reduced blood vessel formation.

Number of blood leukocytes, neutrophils and monocytes were unaffected in anti-CXCL1 and 5 treatments

To determine whether the IL-17-induced arthritis model could be affected by systemic treatment with anti-CXCL1 and/or anti-CXCL5, the number of leukocytes, neutrophils and monocytes were measured in mouse whole blood. Interestingly, all treatment groups had similar numbers of white blood cells, neutrophils and monocytes (Fig. 6a), in contrast to lower levels of joint neutrophils in the anti-CXCL5 and combination therapy (data not shown). These results suggest that although the number of circulating cells was unchanged in the anti-CXCL5 and combination therapy groups, fewer cells migrated into these IL-17-mediated arthritis joints (as shown in H&E staining in Fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 6.

Anti-CXCL5 treatment did not affect the circulating number of leukocytes, neutrophils and monocytes in IL-17-mediated arthritis model and CXCL1 and CXCL5 mediate endothelial migration through CXCR2 ligation. a On day 11 blood was collected by cardiac puncture of IL-17-induced arthritis ankles treated with IgG, anti-CXCL1, anti-CXCL5 or the combination therapy to measure blood cell count using a HemaVet 850 complete blood counter. Values are shown in thousands of cells per microliter of blood (k/μl, n = 10–12 mice). b HMVECs incubated with antibody to CXCR2 (10 μg/ml, R&D systems) were kept at 37°C for 2 h while cells were attaching to the membrane and chemotaxis was examined in response to CXCL1 and CXCL5 (1 and 20 ng/ml; for 2 h at 37°C), n = 2. Values represent fold increase chemotaxis above cells migrating in response to PBS shown as mean ± SE of two experiments in triplicate. * Represents P < 0.05

CXCL1 and CXCL5 mediate endothelial migration through CXCR2 ligation

To demonstrate whether CXCR2 ligation is involved in CXCL1 and CXCL5 function, CXCR2 on endothelial cells was blocked employing anti-CXCR2 neutralizing antibody and subsequently endothelial chemotaxis was examined in response to CXCL1 and CXCL5. Results from these experiments demonstrate that neutralization of CXCR2 on HMVECs significantly decreases CXCL1 (50%) and CXCL5 (40–50%)—mediated endothelial migration (Fig. 6b) suggesting that both chemokines require CXCR2 ligation in order to mediate chemotaxis despite them signaling through different signaling pathways.

CXCL1 and CXCL5 induce endothelial migration through different signaling pathways

To address the different efficacy of blocking CXCL1 and CXCL5 in IL-17 experimental arthritis model we examined the mechanism by which these chemokines induce endothelial migration. We found that in HMVECs, CXCL1 signals through PI3K (35 min) and ERK (35 min) however this chemokine was unable to activate NF-κB or p38 signaling pathways (Figs. 7a). CXCL5 stimulation of HMVECs results in activation of NF-κB pathway (65 min) only (Figs. 7c). To demonstrate the mechanism by which CXCL1 and CXCL5 mediate HMVEC migration, inhibitors to these pathways were employed in in vitro chemotaxis. Interestingly while inhibition of PI3K suppresses CXCL1-induced HMVEC migration, chemotaxis mediated by CXCL5 was reduced through NF-κB inhibition (Figs. 7b, d). These results suggest that endothelial migration is differentially regulated by CXCL1 and CXCL5.

Fig. 7.

CXCL1 and CXCL5 induce endothelial migration through activating different signaling pathways. In order to determine the mechanism by which (a) CXCL1 and (c) CXCL5 activate HMVECs, cells were stimulated with these chemokines (20 ng/ml) for 0–65 min, and the cell lysates were probed for IκB,p-p38, p-AKT,and pERK and/or equal loading controls. To determine signaling pathways associated with b CXCL1 and d CXCL5-induced HMVEC migration, cells were treated with DMSO or inhibitors to NF-κB (MG-132; 1 and 5 μM), p38 (SB203580; 1 and 5 μM), PI3K (LY294002; 1 and 5 μM) and ERK (PD98059; 1 and 5 μM) 2 h in the Boyden chamber, n = 2. Values represent fold increase chemotaxis above cells migrating in response to PBS shown as mean ± SE of two experiments in triplicate. * Represents P< 0.05

Discussion

In this study, we show that CXCL1 and CXCL5 are important downstream mediators of IL-17 in RA synovial cells, RA synovial tissue explants and the IL-17-induced arthritis model. Neutralization of CXCL5, but not CXCL1, ameliorates joint inflammation, bone destruction and vascularization mediated by local expression of IL-17. The differential effect of CXCL1 and CXCL5 blockade in IL-17-induced arthritis model may be due to CXCL5 mediating endothelial migration through a nonoverlapping pathway with IL-17 and CXCL1 despite both chemokines ligation to CXCR2. These results suggest that differential regulation of angiogenesis by CXCL5 can suppress IL-17-induced joint inflammation.

To determine IL-17 downstream targets, RA synovial tissue fibroblasts, macrophages and HMVECs were employed. We found that genes highly induced by IL-17 were potent proangiogenic factors. We also demonstrated that while IL-17-stimulated RA synovial tissue fibroblasts and macrophages express elevated levels of CXCL1 and CXCL5, activated HMVECs demonstrated only higher CXCL1 expression (data not shown). Consistent with our data, others have shown that CXCL1 and CXCL5 expression levels are significantly elevated in IL-17-activated preosteoblast cell line MC3T3-E1 [12]. In macrophages, CXCL1 and CXCL5 are similarly induced by IL-17 through PI3K and ERK pathways. However in RA fibroblasts, CXCL1 and CXCL5 production is differentially regulated by IL-17. Consistently, others have shown that activation of PI3K pathway plays an important role in IL-17-induced CXC chemokine expression in bronchial epithelium cells [37]. In contrast, previous studies demonstrate that IL-17-mediated CXCL1 and 2 expression in RA fibroblasts is suppressed by inhibition of p38 pathway [38]. The inconsistency in the data may be due to differences in passage number, growth condition, methods employed for quantifying mRNA levels (authors determined mRNA after 24 h treatment) [38] or patient treatment employed in the donated RA synovial tissues.

Interestingly, in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts, IL-17 and TNF-α, but not IL-1β, synergize in inducing the expression of CXCL1 and CXCL5. The amplifying effect of IL-17 and TNF-α in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts was very specific to proangiogenic chemokines, and the same effect was not detected for monocyte chemokines such as CCL2 (data not shown). Additionally, this synergistic effect on CXCL1 and CXCL5 was not noted when macrophages or HMVECs were activated with IL-17 and TNF-α, suggesting that the effect was specific to RA synovial tissue fibroblasts. Consistently, others have shown that in RA fibroblasts, IL-17 can synergize with TNF-α and IL-1β in inducing the production of CCL21 [39]. In nonmyeloid cells IL-17-induced stabilization of CXCL1 is independent of AUUUA motif [40] however activator of NF-kappaB1 protein (Act1) is required for this process[41]. While TNF-α mediated transcription of CXC chemokines is driven by NF-κB, this process is modulated by IL-17 through stabilizing the mRNA in an Act1 dependent manner [41]. Hence the synergy between TNF-α and IL-17 may reflect their independent effects on CXC chemokines.

Since both CXCL1 and CXCL5 were significantly elevated in RA synovial tissue explants and IL-17-induced arthritis model to a greater extent than other proangiogenic factors such as FGF2 and VEGF, we asked whether neutralization of one or both of these chemokines could alleviate joint inflammation mediated by local expression IL-17. We found that neutralization of CXCL1 reduced joint inflammation initially on days 3 and 5 post-IL-17 local expression, but was unable to reduce the joint swelling at later time points when arthritis was established. However, CXCL1-mediated endothelial chemotaxis in vitro was markedly reduced by anti-CXCL1 antibody (data not shown). In contrast to anti-CXCL1 treatment, anti-CXCL5 therapy effectively reduced joint inflammation, lining thickness and bone erosion throughout the disease course in the IL-17-induced arthritis model. The combination of anti-CXCL1 and CXCL5 did not ameliorate IL-17-induced joint inflammation beyond the effect observed using anti-CXCL5 alone, indicating that the clinical efficacy was due to blockade of joint CXCL5. Despite elevated levels of FGF2 in IL-17-induced arthritis model, levels of this proangiogenic factor were unaffected by anti-CXCL5 treatment indicating that the efficacy of anti-CXCL5 treatment is directly mediated through CXCR2 ligation. As demonstrated by endothelial chemotaxis data, both CXCL1 and CXCL5 bind to CXCR2, however our results suggest that ligation of these ligands may differentially activate down stream signaling pathways.

Since blockade of CXCL5, but not CXCL1, reduced IL-17 joint vascularization we next examined the mechanism by which these chemokines induce endothelial migration. Interestingly in HMVECs, CXCL1 stimulation resulted in PI3K and ERK signaling whereas only NF-κB pathway was activated by CXCL5 in these cells. Other studies have shown that while stimulation with CXCL1 can phosphorylate ERK1/2 pathway [42-44], activation with CXCL5 is involved with PI3K and NF-κB signaling pathways [45]. We further demonstrate that similar to IL-17 [23], CXCL1 mediated HMVEC migration is through PI3K activation. In contrast, inhibition of NF-κB suppresses endothelial chemotaxis induced by CXCL5. Perhaps inhibition of CXCL1 is ineffective in reducing joint inflammation since IL-17 is present in the mouse ankles (1,200 pg/mg and 400 pg/mg on days 4 and 10 post injection respectively [27]) and can induce angiogenesis through the same mechanism. In line with our finding others have shown that CXCL1 and 5 can differentially modulate monocyte arrest and migration [46], suggesting that ligands binding to the same receptor can have distinct functions through activating different signaling intermediates.

Reduction in joint TNF-α levels in the anti-CXCL5 and combination therapy may be due to the fact that IL-17-induced joint pathology is abrogated in TNF-α deficient mice, indicating that in this model TNF-α is required [3]. It has also been shown that IL-17 can directly modulate TNF-α secretion from macrophages [47]. Hence, suppressing IL-17-induced inflammation may reduce TNF-α production from macrophages in the synovial lining and sublining. Further, both TNF-α and IL-17 synergize in inducing the expression of CXCL5 from RA fibroblasts. Therefore, neutralization of CXCL5 may have a negative feed back regulation on joint TNF-α concentrations. When RA synovial tissue fibroblasts, macrophages and HMVECs were screened for IL-17 downstream targets, CCL5 was undetected (data not shown). Therefore, reduction in joint CCL5 concentration in anti-CXCL5 and combination therapy treatment groups may be due to reduced TNF-α levels, since CCL5 expression is known to be modulated by TNF-α in RA synovial tissue fibroblasts [48, 49].

In conclusion, anti-CXCL5 treatment ameliorates IL-17-mediated arthritis by down regulating TNF-α and joint vascularization through an IL-17 nonoverlapping mechanism. These data support angiogenesis as an important mechanism by which IL-17 contributes to RA pathogenesis, further supporting IL-17 as a potential therapeutic target in RA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health AR056099, AR055240 and grants from Within Our Reach from The American College of Rheumatology Arthritis National Research Foundation, as well as funding provided by the Department of Defense PR093477.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards All experiments performed comply with the current laws of United States of America.

Contributor Information

Sarah R. Pickens, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, MSB 835S Wolcott Ave., E807-E809, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

Nathan D. Chamberlain, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, MSB 835S Wolcott Ave., E807-E809, Chicago, IL 60612, USA

Michael V. Volin, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine, Midwestern University, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA

Mark Gonzalez, Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612, USA.

Richard M. Pope, Department of Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA

Arthur M. Mandelin, II, Department of Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA.

Jay K. Kolls, Department of Genetics, LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA

Shiva Shahrara, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, MSB 835S Wolcott Ave., E807-E809, Chicago, IL 60612, USA.

References

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, et al. Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:650–659. doi: 10.1002/art.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenders MI, Lubberts E, van de Loo FA, et al. Interleukin-17 acts independently of TNF-alpha under arthritic conditions. J Immunol. 2006;176:6262–6269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, Oppers B, et al. IL-1-independent role of IL-17 in synovial inflammation and joint destruction during collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;167:1004–1013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koenders MI, Lubberts E, Oppers-Walgreen B, et al. Induction of cartilage damage by overexpression of T cell interleukin-17A in experimental arthritis in mice deficient in interleukin-1. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:975–983. doi: 10.1002/art.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, et al. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:6173–6177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarzenberger P, La Russa V, Miller A, et al. IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis in mice: use of an alternate, novel gene therapy-derived method for in vivo evaluation of cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:6383–6389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forlow SB, Schurr JR, Kolls JK, et al. Increased granulopoiesis through interleukin-17 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in leukocyte adhesion molecule-deficient mice. Blood. 2001;98:3309–3314. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luzza F, Parrello T, Monteleone G, et al. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J Immunol. 2000;165:5332–5337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zrioual S, Toh ML, Tournadre A, et al. IL-17RA and IL-17RC receptors are essential for IL-17A-induced ELR + CXC chemokine expression in synoviocytes and are overexpressed in rheumatoid blood. J Immunol. 2008;180:655–663. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen F, Gaffen SL. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine. 2008;41:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith JB, et al. Interleukin-17 regulates expression of the CXC chemokine LIX/CXCL5 in osteoblasts: implications for inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:135–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witowski J, Pawlaczyk K, Breborowicz A, et al. IL-17 stimulates intraperitoneal neutrophil infiltration through the release of GRO alpha chemokine from mesothelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5814–5821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szekanecz Z, Pakozdi A, Szentpetery A, et al. Chemokines and angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2009;1:44–51. doi: 10.2741/e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szekanecz Z, Besenyei T, Paragh G, et al. New insights in synovial angiogenesis. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;77:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch AE, Kunkel SL, Harlow LA, et al. Epithelial neutrophil activating peptide-78: a novel chemotactic cytokine for neutrophils in arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1012–1018. doi: 10.1172/JCI117414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich N, Beyer C, Gelse K, et al. Microparticles stimulate angiogenesis by inducing ELR(+) CXC-chemokines in synovial fibroblasts. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:756–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch AE, Volin MV, Woods JM, et al. Regulation of angiogenesis by the C-X-C chemokines interleukin-8 and Epithelial Neutrophil Activating Peptide 78 in the rheumatoid joint. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:31–40. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200101)44:1<31::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podolin PL, Bolognese BJ, Foley JJ, et al. A potent and selective nonpeptide antagonist of CXCR2 inhibits acute and chronic models of arthritis in the rabbit. J Immunol. 2002;169:6435–6444. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagari T, Tanaka D, Doi H, et al. Anti-type II collagen antibody accelerates arthritis via CXCR2-expressing cells in IL-1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2753–2763. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coelho FM, Pinho V, Amaral FA, et al. The chemokine receptors CXCR1/CXCR2 modulate antigen-induced arthritis by regulating adhesion of neutrophils to the synovial microvasculature. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2329–2337. doi: 10.1002/art.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickens SR, Volin MV, Mandelin AM, II, et al. IL-17 contributes to angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2010;184:3233–3241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahrara S, Castro-Rueda HP, Haines GK, et al. Differential expression of the FAK family kinases in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis synovial tissues. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R112. doi: 10.1186/ar2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahrara S, Park CC, Temkin V, et al. RANTES modulates TLR4-induced cytokine secretion in human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177:5077–5087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahrara S, Pickens SR, Mandelin AM, II, et al. IL-17-mediated monocyte migration occurs partially through CC chemokine ligand 2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induction. J Immunol. 2010;184:4479–4487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahrara S, Pickens SR, Dorfleutner A, et al. IL-17 induces monocyte migration in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3884–3891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shahrara S, Huang Q, Mandelin AM, II, et al. TH-17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 10:R93. doi: 10.1186/ar2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahrara S, Volin MV, Connors MA, et al. Differential expression of the angiogenic Tie receptor family in arthritic and normal synovial tissue. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:201–208. doi: 10.1186/ar407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahrara S, Proudfoot AE, Woods JM, et al. Amelioration of rat adjuvant-induced arthritis by Met-RANTES. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1907–1919. doi: 10.1002/art.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahrara S, Proudfoot AE, Park CC, et al. Inhibition of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 ameliorates rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;180:3447–3456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scatizzi JC, Bickel E, Hutcheson J, et al. Bim deficiency leads to exacerbation and prolongation of joint inflammation in experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3182–3193. doi: 10.1002/art.22133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruth JH, Volin MV, Haines GK, III, et al. Fractalkine, a novel chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis and in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1568–1581. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1568::AID-ART280>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch AE, Nickoloff BJ, Holgersson J, et al. 4A11, a monoclonal antibody recognizing a novel antigen expressed on aberrant vascular endothelium. Upregulation in an in vivo model of contact dermatitis. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:244–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park CC, Morel JC, Amin MA, et al. Evidence of IL-18 as a novel angiogenic mediator. J Immunol. 2001;167:1644–1653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang F, Kao CY, Wachi S, et al. Requirement for both JAK-mediated PI3K signaling and ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1-dependent NF-kappaB activation by IL-17A in enhancing cytokine expression in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:6504–6513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kehlen A, Thiele K, Riemann D, et al. Expression, modulation and signalling of IL-17 receptor in fibroblast-like synoviocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;127:539–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chabaud M, Page G, Miossec P. Enhancing Effect of IL-1, IL-17, and TNF-alpha on Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-3alpha Production in Rheumatoid Arthritis: regulation by Soluble Receptors and Th2 Cytokines. J Immunol. 2001;167:6015–6020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Datta S, Novotny M, Pavicic PG, Jr, et al. IL-17 regulates CXCL1 mRNA stability via an AUUUA/tristetraprolin-independent sequence. J Immunol. 2010;184:1484–1491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, et al. IL-17 enhances chemokine gene expression through mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 2007;179:4135–4141. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D, Sai J, Richmond A. Cell surface heparan sulfate participates in CXCL1-induced signaling. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1071–1077. doi: 10.1021/bi026425a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang G, Rosen DG, Zhang Z, et al. The chemokine growth-regulated oncogene 1 (Gro-1) links RAS signaling to the senescence of stromal fibroblasts and ovarian tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16472–16477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605752103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Filipovic R, Zecevic N. The effect of CXCL1 on human fetal oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia. 2008;56:1–15. doi: 10.1002/glia.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandrasekar B, Melby PC, Sarau HM, et al. Chemokine-cytokine cross-talk. The ELR + CXC chemokine LIX (CXCL5) amplifies a proinflammatory cytokine response via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-NF-kappa B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4675–4686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith DF, Galkina E, Ley K, et al. GRO family chemokines are specialized for monocyte arrest from flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1976–H1984. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00153.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jovanovic DV, Di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, et al. IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-beta and TNF-alpha, by human macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:3513–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rathanaswami P, Hachicha M, Sadick M, et al. Expression of the cytokine RANTES in human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5834–5839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nanki T, Nagasaka K, Hayashida K, et al. Chemokines regulate IL-6 and IL-8 production by fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5381–5385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]