Abstract

Purpose:

This study evaluated powdered burn wound dressing materials from wild silkworm fibroin in an animal model.

Methods:

Fifteen rats were used in this experiment. Full-thickness 2×2 cm burn wounds were created on the back of rats under anesthesia. In the two experimental groups, the wounds were treated with two different dressing materials made from silkworm fibroin. In the Control Group, natural healing without any dressing material was set as control. The wound surface area was measured at five days, seven days and 14 days. Wound healing was evaluated by histologic analysis.

Results:

By gross observation, there were no infections or severe inflammations through 14 days post-injury. The differences among groups were statistically significant at seven days and 14 days, postoperatively (P <0.037 and 0.001, respectively). By post hoc test, the defect size was significantly smaller in experimental Group 1 compared with the Control Group and experimental Group 2 at seven days postoperatively (P =0.022 and 0.029, respectively). The difference between Group 1 and Group 2 was statistically significant at 14 days postoperatively (P <0.001). Group 1 and control also differed significantly (P =0.002). Group 1 showed a smaller residual scar than the Control Group and Group 2 at 14 days post-injury. Histologic analysis showed more re-epithelization in Groups 1 and 2 than in the Control Groups.

Conclusion:

Burn wound healing was accelerated with silk fibroin spun by wild silkworm Antheraea pernyi. There was no atypical inflammation with silk dressing materials. In conclusion, silk dressing materials can be used for treatment of burn wound.

Keywords: Full thickness burn wound, Wound dressing, Silk fibroin, Antheraea pernyi, Rats

Introduction

Wound healing is a very complex process with many cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions to regenerate injured tissues [1]. Wound dressing is applied to protect damaged tissue and enhance the natural healing process without infection. There are several criteria for ideal wound dressing materials: (1) biocompatibility, (2) prevention of dehydration and retention of a favorable moist environment, (3) protection from foreign bodies and micro-organisms, (4) promotion of epithelialization, (5) non-adhesion [2].

Burn wounds are difficult to manage because this type of wound exudes heavily and induces adhesion during the healing process [3]. This adhesion easily causes secondary trauma when wound dressing materials are removed. Traditionally, mesh dressing materials have been used for management of burn wounds, although this type of material can cause secondary trauma during removal. Kanokpanont et al. [2] studied wax-coated biomaterials to prevent secondary trauma. However, wax-coated biomaterials requires complex laboratory processes and may reduce the healing activity of the biologically derived biomaterials.

Silkworm produced material (SM) has been widely used as surgical suture and textile fiber for many centuries [4]. SM has many properties suitable for wound dressing: biocompatibility, minimal inflammatory reaction, capability to promote wound healing, strength, toughness, light weight, and easy chemical modification [5]. Therefore, SM has been studied for guided bone regeneration membrane, bone regeneration scaffold, and wound dressing materials [6–12].

In this experiment we use SM as powdered dressing materials for two reasons. (1) It readily absorbs the exudate and retains a favorable moist environment. (2) It is non-adhesive to the burn wound, thus preventing secondary trauma upon removal. The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of these powdered wound dressing materials made from silk fibroin spun by wild silkworm Antheraea pernyi on full thickness burn wounds on rats.

Materials and Methods

1. Silk dressing materials

In this experiment, we used two different dressing materials obtained from wild silkworm A. pernyi. Wild silkworm A. pernyi cocoon harvested from the Rural Development Administration facility (Suwon, Korea) was used for the experiments. Two different processing methods were used. For experimental Group 1, the cocoon was degummed with carbonate solution and dissolved following published methods [13]. For experimental Group 2, the cocoon was dissolved in molten calcium nitrate 4 hydrate and then freeze-dried. Powdered silk material was prepared from wild silk membranes by grinding. As a result, Group 1 had narrow spectrum of molecular weight. However, Group 2 had wide spectrum of molecular weight, particularly had abundant low molecular weight silk fibroin.

2. Experimental animals and housing conditions

Fifteen Sprague-Dawley rats with body weights of 250 to 300 g were obtained from SAMTAKO BIO KOREA Co. (Osan, Korea) at 12 weeks of age. Each rat was housed in a separate stainless steel cage and allowed to adapt for ten days before the main experiment. The animals were maintained on a 12 hours dark/light cycle at about 22°C±3°C and allowed free access to standard laboratory diet and tap water ad libitum during experiments. This experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gangneung-Wonju National University (GWNU 2013-29).

3. Animal experiments

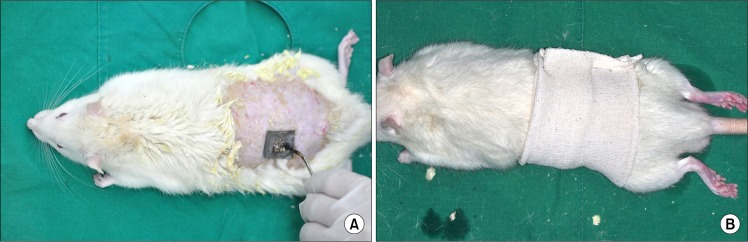

At the beginning of experiment, general anesthesia was induced with 0.2 mL Tiletamine and Zolawepam (125 mg/mL, Zoletil; Bayer Korea, Seoul, Korea) and 0.1 mL xylazine (10 mg/kg body weight, Rompun; Bayer Korea). The back of each animal was shaved, and a 2×2 cm size standard second degree burn was produced on the back of each rat with hot stamps (Fig. 1A). Two defects were created for each rat, resulting in 30 defects that were randomly divided into three groups. In the Control Group, the wounds were dressed simply without any application. In two different experimental groups, two types of dressing materials were applied to the wounds. Every burn wound was covered with an occlusive dressing (Fig. 1B). At five days post-injury, occlusive dressings were removed and clinical signs and healing states were observed. Inflammation signs, bleeding from secondary trauma, and other clinical abnormalities were checked. We photographed the burn wound at five, seven, and 14 days post-injury, and measured the residual denuded surface using size measuring software (SigmaScan-Pro®; SPSS Science, Chicago, IL, USA).

Fig. 1.

Burn Injury model. (A) A second degree burn injury of 2×2 cm size was created on the back of the rat using stamp. We created two defects for each rat. (B) Occlusive dressings were done for every animal (both silkworm produced material Groups and Control Group) during the five days post-injury.

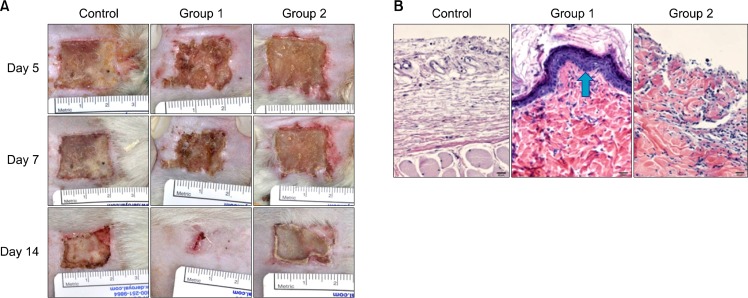

4. Histologic analysis

Animals were sacrificed at 14 days post-injury and the remaining scar area was excised and prepared for histologic exam. Tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate the infiltration of inflammatory cells including macrophages and giant cells that indicated the extent of foreign body reaction (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

(A) Clinical photos of healing process. Group 1 developed smaller residual scars than Control Group and Group 2 at 14 days post-injury. (B) Histology (H&E, ×400) of each Groups. Group 1 (arrow) and 2 show more re-epithelialization than Control Groups. There was no evidence of severe inflammation for any samples.

5. Statistical analysis

All the results were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post hoc test (least significant difference method). Null hypotheses of no difference were rejected if P-values were less than 0.05.

Results

In gross observation, there were no infections or severe inflammation noted through 14 days post-injury (Fig. 2A). No groups had bleeding tendencies at the time of dressing removal at five days post-injury. All wounds seemed stable although with different degrees of healing areas.

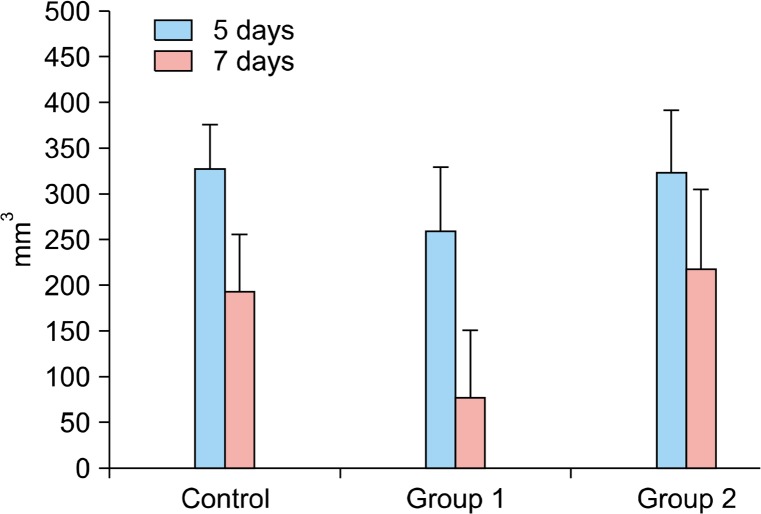

There was no significant difference among groups at five days post-injury (P >0.05). However, the differences among groups were statistically significantly different at seven days and 14 days, postoperatively (P <0.037 and 0.001, respectively). By a post hoc test, the defect sizes were significantly smaller in Group 1 compared with Control Group and Group 2 at seven days postoperatively (P <0.022 and 0.029, respectively). A similar trend was observed at 14 days postoperatively. The difference between Group 1 and Group 2 was statistically significant at 14 days postoperatively (P <0.001). The difference between Group 1 and Control Group was also statistically significant (P <0.002). Group 1 has a smaller residual scar than the Control Group and Group 2 at post-injured 14 days (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

De-nuded area at post-injured days five and seven in each group (mm3).

In histologic analysis, Groups 1 and 2 developed more re-epithelization than controls. No evidence of severe inflammation was found. There were minimal numbers of inflammatory cells responding to infection or foreign body reactions (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

SM is widely used for tissue engineering because of appropriate physical, mechanical and biological properties including strength, toughness, elasticity, lightweight, biocompatibility, biodegradability, minimal inflammatory reaction, capability to promote wound healing, and easy chemical modification to suit the applications [2]. Various clinical applications for SM are being explored because of its ability to prevent adhesion and promote proliferation of various cells including keratinocytes and fibroblasts [6–12]. SM also is used in bioactive wound dressings in various formulations [12,14,15]. In this study we observed the positive result of powdered silk dressing materials as a burn dressing materials.

Traditionally, the burn wound is treated with mesh-type dressing materials [3]. After the wound is healed, the dressing is removed. Mesh dressings tend to attach to the burn wound, resulting in secondary trauma and risk of repeated injury. Thus, non-adhesive dressing materials like wax coated dressing material for burn wound dressing are being studied [2]. However, wax coating presents problems such as reducing the healing potential of the original materials. In this study, SM resulted in little secondary trauma on burn wounds. This may be because the powdered wound dressings are less adhesive than the commercial wound dressing mesh, since powdered SM loosely adheres to the hydrophilic wound surface. In histologic analysis, powdered SM resulted in minimal inflammation reactions to the burn wound (Fig 2B).

Nano-silver dressing materials were recently assessed for burn wound management. These have potent anti-microbial properties, so may be useful for preventing wound infections. However, these materials have limitations like wound pigmentation and hepatotoxicity at high doses [16]. There are reports that wound dressings made of SM can successfully heal the wound [12,14,15,17]. Baoyong et al. [17] used recombinant spider silk protein as a wound dressing for second-degree burn wounds in rat model. They found that the recombinant spider silk protein membrane promoted wound skin recovery by increasing the expression and secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and hydroxyproline. Vasconcelos et al. [18] fabricated novel silk fibroin/elastin scaffolds for burn wounds treatment. Although SM wound dressings are being successfully applied, only a few researchers focus on the adhesive property of the dressings to the wound bed.

This study developed a powdered wound dressing applied to the wound surface that absorbs wound fluid while accelerating healing. The modification of SM by grinding was to prepare a non-adhesive wound dressing that can be easily detached from a wound without trauma. In addition, our SM powdered dressing is advantageous in terms of friction reduction and dehydration prevention for the wound. Histologic analysis revealed no evidence of severe inflammation (Fig. 2B), with minimal inflammatory cells including macrophages and giant cells. This confirmed the feasibility of powdered SM as wound dressing materials.

The results of this study show good healing of burn wounds with minimal infection or inflammation (Fig. 2A). These results indicate the capability of silk fibroin dressing materials to promote wound healing [2]. Powdered dressing material can absorb the fluid easily from the burn wound during the initial healing period. This provides a more appropriate environment for burn wounds healing, and the powdered dressing detached from the wound spontaneously with the re-epithelization process. Therefore, there was little secondary trauma on the burn wounds.

Based on our data, the powdered SM is a promising candidate for burn wound dressing. However, prior to clinical applications of this dressing, more research to improve the properties of this dressing material is needed. It is suggested that including tetracyclines or 4-hour will enhance the antimicrobial properties of these materials [7,19].

Conclusion

Silk dressing materials from wild silkworm A. pernyi fibroin showed good biocompatibility as burn wound dressing materials. Wound healing with silk dressing material showed better re-epithelization in groups 1 and 2, and the silk dressing material showed minimal foreign body reaction. In conclusion, silk dressing materials can be used for treatment of burn wound.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Research Program for Agricultural Science & Technology Development (PJ906973) and Next-Generation BioGreen21 Program (Center for Nutraceutical & Pharmaceutical Materials no. PJ009051), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–29. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanokpanont S, Damrongsakkul S, Ratanavaraporn J, Aramwit P. Physico-chemical properties and efficacy of silk fibroin fabric coated with different waxes as wound dressing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;55:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosselin RA, Kuppers B. Open versus closed management of burn wounds in a low-income developing country. Burns. 2008;34:644–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Shin BS, Jeon JY, et al. Tetracycline-incorporated Silk Fibroin Films. Int J Industr Entomol. 2012;25:129–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panilaitis B, Altman GH, Chen J, Jin HJ, Karageorgiou V, Kaplan DL. Macrophage responses to silk. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3079–85. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song JY, Kim SG, Lee JW, et al. Accelerated healing with the use of a silk fibroin membrane for the guided bone regeneration technique. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SW, Park YT, Kim SG, Kweon HY, Jo YY, Lee HS. The effects of tetracycline-loaded silk fibroin membrane on guided bone regeneration in a rabbit calvarial defect model. J Korean Assoc Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;34:293–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park YT, Kwon KJ, Park YW, et al. The effect of silk fibroin/nano-hydroxyapatite/corn starch composite porous scaffold on bone regeneration in the rabbit calvarial defect model. J Korean Assoc Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;33:459–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kweon H, Lee KG, Chae CH, et al. Development of nano-hydroxyapatite graft with silk fibroin scaffold as a new bone substitute. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1578–86. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang ES, Park JW, Kweon H, et al. Restoration of peri-implant defects in immediate implant installations by Choukroun platelet-rich fibrin and silk fibroin powder combination graft. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:831–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee EH, Kim JY, Kweon HY, et al. A combination graft of low-molecular-weight silk fibroin with Choukroun platelet-rich fibrin for rabbit calvarial defect. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roh DH, Kang SY, Kim JY, et al. Wound healing effect of silk fibroin/alginate-blended sponge in full thickness skin defect of rat. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:547–52. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-8938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kweon H, Park YH. Dissolution and characterization of regenerated Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;82:750–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kweon H, Yeo JH, Lee KG, et al. Semi-interpenetrating polymer networks composed of silk fibroin and poly(ethylene glycol) for wound dressing. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:034115. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarini A, Petrini P, Bozzini S, Dal Pra I, Armato U. Silk fibroin/poly(carbonate)-urethane as a substrate for cell growth: in vitro interactions with human cells. Biomaterials. 2003;24:789–99. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bidgoli SA, Mahdavi M, Rezayat SM, Korani M, Amani A, Ziarati P. Toxicity assessment of nanosilver wound dressing in Wistar rat. Acta Med Iran. 2013;51:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baoyong L, Jian Z, Denglong C, Min L. Evaluation of a new type of wound dressing made from recombinant spider silk protein using rat models. Burns. 2010;36:891–6. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasconcelos A, Gomes AC, Cavaco-Paulo A. Novel silk fibroin/elastin wound dressings. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:3049–60. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SW, Kim SG, Song JY, et al. Silk fibroin and 4-hexylresorcinol incorporation membrane for guided bone regeneration. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1927–30. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182a3050c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]