Abstract

Conditioned defeat is a model in Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) in which normal territorial aggression is replaced by increased submissive and defensive behavior following acute social defeat. The conditioned defeat response involves both a fear-related memory for a specific opponent as well as anxiety-like behavior indicated by avoidance of novel conspecifics. We have previously shown that systemic injection of a 5-HT2a receptor antagonist reduces the acquisition of conditioned defeat. Because neural activity in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) is critical for the acquisition of conditioned defeat and BLA 5-HT2a receptors can modulate anxiety but have a limited effect on emotional memories, we investigated whether 5-HT2a receptor modulation alters defeat-induced anxiety but not defeat-related memories. We injected the 5-HT2a receptor antagonist MDL 11,939 (0 mM, 1.7 mM or 17 mM) or the 5-HT2a receptor agonist TCB-2 (0 mM, 8 mM or 80 mM) into the BLA prior to social defeat. We found that injection of MDL 11,939 into the BLA impaired acquisition of the conditioned defeat response and blocked defeat-induced anxiety in the open field, but did not significantly impair avoidance of former opponents in the Y-maze. Furthermore, we found that injection of TCB-2 into the BLA increased the acquisition of conditioned defeat and increased anxiety-like behavior in the open field, but did not alter avoidance of former opponents. Our data suggest that 5-HT2a receptor signaling in the BLA is both necessary and sufficient for the development of conditioned defeat, likely via modulation of defeat-induced anxiety.

1. Introduction

Stressful life events are a critical risk factor in the etiology of depression (Heim & Nemeroff, 2001; Kendler et al., 1999) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kuo et al., 2003; Risbrough & Stein, 2006; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002). Furthermore, psychosocial stress is becoming an exceedingly common form of stress in westernized societies (Cryan and Slattery, 2007). Although both psychosocial and physical stressors elicit a robust neuroendocrine stress response, they can activate distinct neural circuits (Lopez et al., 1999; Toth & Neumann, 2013). Therefore animal models of social stress are particularly useful for investigating neurobiological mechanisms underlying stress-related mental illness (Blanchard et al., 1995; Nestler & Hyman, 2010; Potegal et al., 1993). We use an acute social defeat model in Syrian hamsters called conditioned defeat (CD), in which a single social defeat results in a loss of normal territorial aggression and an increase in submissive and defensive behavior in later non-aggressive social encounters (Huhman et al., 2003). Recently, it was shown that Syrian hamsters are capable of recognizing and selectively avoiding former opponents 24 hours following social defeat (McCann & Huhman, 2012). Syrian hamsters also show greater avoidance of a familiar winner compared to an unfamiliar winner in a Y-maze test (Lai & Johnston, 2002; Lai et al., 2005). Avoidance of familiar winners appears to involve a fear-related memory in part, because systemic administration of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin blocks defeat-induced social avoidance in the Y-Maze (Huang et al., 2011). Together, these studies suggest that conditioned defeat involves fear-related behavior and a memory for social defeat. On the other hand, social defeat has been shown to increase anxiety-like behavior in an open field test as indexed by reduced locomotion and reduced time spent in the center of the arena (Raab et al., 1986, Meerlo et al., 1996, Kinsey et al., 2007). Also, Syrian hamsters generalize social avoidance to novel intruders suggesting that conditioned defeat involves an increase in anxiety-like behavior (Bader et al., 2014).

Synaptic transmission within the basolateral amygdala (BLA) is essential for the generation of aversive emotional responses and the formation of emotional memories (LeDoux, 2003). The BLA is a critical neural substrate regulating the formation of CD and conditioned fear. NMDA receptor antagonists injected into the BLA block the acquisition of CD and fear-potentiated startle (Fanselow et al., 1994; Jasnow et al., 2004). Over-expression of CREB in the BLA using vector-mediated gene transfer enhances the acquisition of CD and fear-potentiated startle (Jasnow et al., 2005; Josselyn et al., 2001). Also, blocking protein synthesis in the BLA with anisomycin impairs the acquisition of CD and conditioned fear (Markham & Huhman, 2008; Schafe & LeDoux, 2000). Activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc) is an immediate early gene and a commonly used marker of synaptic plasticity, as it is necessary for the consolidation of long-term memory (Ploski et al., 2008). Recently, we showed that social defeat increases the expression of Arc in the BLA of Syrian hamsters (Bader et al., 2014), which is consistent with other research showing that Arc in the lateral amygdala is necessary for the reconsolidation of auditory fear conditioning (Maddox & Schafe, 2011). Taken together, these findings suggest that the acquisition of conditioned fear and CD is regulated by a similar set of cellular and molecular mechanisms in the BLA.

Serotonin (5-HT) is a neurochemical that plays a well-known role in the etiology and treatment of stress-related mental illness (Harvey et al., 2004; Vieweg et al., 2006). Activation of 5-HT pathways from the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) to cortical and limbic brain regions has been shown to enhance the development of stress-induced changes in behavior (Cooper et al., 2008; Maier & Watkins, 2005). However, the brain regions and receptors that mediate the effect of 5-HT on the CD response remain largely unresolved. 5-HT2a receptors are good candidates because we have previously shown that systemic blockade of 5-HT2a receptors impairs the acquisition of CD (Harvey et al., 2012). 5-HT2a receptors have been localized to both BLA pyramidal neurons and GABAergic interneurons positive for the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (PV) (Bombardi, 2011; McDonald & Mascagni, 2007). Activation of 5-HT2a receptors in vitro has been shown to depolarize BLA interneurons and indirectly hyperpolarize pyramidal neurons (Rainnie, 1999). However, activation of 5-HT2a receptors was recently shown to directly inhibit BLA pyramidal neurons by suppressing excitatory post-synaptic potentials in the presence of the GABA receptor antagonist bicuculline and by increasing the action potential threshold in pyramidal cells (McCool et al., 2014). Importantly, stress and anxiogenic drugs may down-regulate 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA and potentiate the emergence of anxiety-like behavior. Three consecutive days of immobilization with tail-shocks has been shown to down regulate 5-HT2a receptors and lead to hyperexcitability of BLA pyramidal cells (Jiang et al., 2009). Also, systemic blockade of 5-HT2a receptors has been shown to prevent stress-induced elevation of acoustic startle possibly by preventing the down-regulation of 5-HT2a receptors (Jiang et al., 2011). Furthermore, anxiogenic drugs targeting 5-HT2a receptors were found to increase c-Fos expression in PV-positive interneurons in the BLA, which correlated with the number of c-Fos immunoreactive 5-HT cells in the DRN and levels of anxiety-like behavior (Hale et al., 2010). Overall, 5-HT2a receptors are capable of regulating the activity of BLA pyramidal neurons and controlling the emergence of stress-induced anxiety-like behavior.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether 5-HT2a receptors within the BLA regulate the acquisition of CD, and whether they do so by modulating fear and/or anxiety. We hypothesized that blockade of BLA 5-HT2a receptors prior to social defeat would impair the acquisition of CD by blocking defeat-induced anxiety, but not defeat-related fear memory. Similarly, we hypothesized that activation of BLA 5-HT2a receptors prior to social defeat would increase the acquisition of CD by increasing defeat-induced anxiety, but not defeat-related fear memory.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

We used male Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) that weighed 130–170 g (3–4 months old) at the start of the study. Older hamsters (> 200 g) were individually housed and used as resident aggressors (RAs) for social defeat training. Younger hamsters (90 – 100 g, approximately 2 months old) were group-housed (4 per cage) and used as non-aggressive intruders for CD testing. All animals were housed in polycarbonate cages (12 cm × 27 cm × 16 cm) with corncob bedding, cotton nesting materials, and wire-mesh tops. Animal cages were not changed for at least one week prior to testing to allow individuals to scent mark their territory. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled colony room (20 ± 2 °C) and maintained on a 14:10 h light:dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Subjects were handled for 7–10 days prior to social defeat training to habituate them to the stress of human contact. All behavioral testing occurred in the first three hours of the dark phase. All procedures were approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and follow the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Stereotaxic surgery

Hamsters were anesthetized with isoflurane and stereotaxically implanted bilaterally with 26-gauge guide cannulae aimed at the BLA. The stereotaxic coordinates were 0.4 mm posterior and 3.9 mm lateral to bregma, and 2.2 mm below dura. Cannulas were fixed to the skull with acrylic cement, a wound clip, and tissue adhesive. After surgery, dummy stylets that projected 0.1 mm below the guide cannulae were inserted to avoid obstruction of the cannulae until infusions were performed. During microinjection, a 33-gauge injection needle was inserted that projected 4.0 mm below the guide cannula for a final projection of 6.2 mm below dura. Animals were given 7–10 days to recover from surgery before starting behavioral experiments.

2.3. Social defeat training

In experiment 1, social defeat training consisted of three, 5 min aggressive encounters in the home cage of a larger RA with 5 min rests in the subjects’ home cage between each defeat. To ensure that every subject received similar amounts of aggression from the RA, timing of the first defeat did not begin until the first attack, which usually occurred within the first 60 seconds of the encounter. Because we expected TCB-2 to increase the CD response in experiment 2, subjects received a single suboptimal 5 min social defeat to avoid a ceiling effect on later submissive/defensive behavior at testing. Defeats were digitally recorded and the behavior of the RA was quantified later using Noldus Observer (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). We quantified total number of attacks and total duration of aggression displayed. Any animal with a wound extending beyond the epidermis and into the dermis layer was treated and removed from the study. To evaluate whether drug treatment altered behavior at testing in the absence of social defeat, we included no defeat control groups. No defeat control animals were placed in the empty cages of three different RA’s for 5 mins each (experiment 1) or placed in the empty cage of one RA for 5 min (experiment 2) so that they experienced similar olfactory cues and novel environment as the defeated animals.

2.4. Conditioned defeat testing

CD testing consisted of a 5 min social interaction test, during which a non-aggressive intruder was placed in the subject’s cage. Non-aggressive intruders were younger, group-housed animals that displayed social and nonsocial behavior, and at testing we excluded those intruders that displayed agonistic behavior. All testing sessions were digitally recorded and the behavior of the subject was quantified using Noldus Observer by a researcher blind to the experimental conditions. We quantified the total duration of the following categories of behavior: submissive/defensive (flee, avoid, upright and side defensive postures, tail-up, stretch-attend); aggressive (chase, attack, upright and side offensive postures); social (sniffing and approach); and nonsocial (locomotion, grooming, nesting, and feeding) (Albers et al., 2002). We also quantified the frequency of flees, stretch-attend postures, and attacks displayed by the subject. On a subset of videos, inter-rater reliability in the duration of submissive/defensive behavior was >90% agreement.

2.5. Apparatuses: Y-maze

To evaluate avoidance of familiar aggressors we used a Y-maze test as previously described (Bader et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2005). The Y-maze was divided into eight rectangular boxes (10 cm wide × 10 cm high). The base of the Y (89 cm long) was divided into start box (20 cm) and stem (69 cm), and the two arms of the maze were 70 cm long and were divided into 3 sections. The sections closest to the stem were the basal parts (25 cm) of the arm while the compartments farther from the base are the distal parts (25 cm) of the arm. Subjects had access to all compartments of the Y-maze except for the most distal parts of the Y, which were the stimulus boxes (20 cm) where the stimulus animal was located during testing. The stimulus animal and subject were separated through a perforated Plexiglas wall (0.8 cm thick) to allow for the movement of air throughout the Y-maze. The screen in front of the stimulus box was permanent whereas the screen that separates the start box from the stem was removable to allow the subject to explore the maze. Air was drawn from the stimulus boxes to the start box by a fan mounted on the outside of the start box.

Y-maze testing consisted of two, 3-minute trials. The first trial was an empty trial to determine the animal’s preferred arm of the Y-maze. In the second trial, the RA from the first defeat was placed in the stimulus box of the subject’s preferred arm to avoid confounding side preferences with avoidance of the RA. For no defeat control subjects, the RA whose cage was explored first during empty cage exposure was placed in the stimulus box. The Y-maze was cleaned with 70% ethanol after each subject was tested to remove any residual odors. All trials were digitally recorded and behavior was quantified using Noldus Observer by a researcher blind to experimental conditions. For each subject we recorded the amount of time spent in 6 compartments: the start box, the stem of the Y, the basal part of each arm, and the distal part of each arm. The position of the subject within the Y-maze was determined by the location of its nose, and time spent in the distal compartment near the stimulus indicated proximity to the RA. We also scored the amount of time spent in olfactory investigation (i.e. sniffing), which is defined as time spent by the subject with its nose 2 cm from the stimulus box.

2.5.1. Open field

Subjects were tested for 5 min in a brightly lit open field arena, which was an 80 × 80 × 40 cm acrylic box with black sides and a white floor. In experiment 1, subjects were placed underneath a plastic shelter in one corner of the open field at the start of the trial in order to measure latency to withdraw from the shelter into the open field. The shelter was used to test for defensive withdrawal (Roman & Arborelius, 2009), but after several subjects spent the entire test session exploring, climbing on and moving the novel shelter around the arena, we decided to remove the shelter in experiment 2. In experiment 2, subjects were placed in one corner of the arena with their nose facing the corner at the start of the trial. The open field was cleaned between each trial with 70% ethanol to remove any residual odors left by the subject. Tests were digitally recorded and scored by an observer blind to the experimental conditions using Noldus EthoVision XT (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). We quantified the latency to exit the shelter and total duration in the shelter (experiment 1 only), total distance traveled, and total duration of center time.

2.6. Drugs

MDL 11,939 (Tocris Bioscience) was dissolved in sterile saline with 1% acetic acid and 10% sodium hydroxide (pH = 5.5), which was used as a vehicle control at a similar pH. MDL 11,939 is a highly selective 5-HT2a receptor antagonist (Dudley et al., 1988). TCB-2 (Tocris Bioscience) was dissolved in sterile saline with 10% DMSO. TCB-2 is a highly selective agonist for the 5-HT2a receptor (Fox et al., 2010). MDL 11,939, TCB-2 and saline vehicles were microinjected at volumes of 200 nl per side.

2.7. Experiment 1

We designed experiment 1 to test whether injection of a 5-HT2a receptor antagonist into the BLA prior to social defeat would decrease the acquisition of CD. We bilaterally infused MDL 11,939 (1.7 mM, N = 9 or 17 mM, N = 9) or vehicle (N = 10) into the BLA 10 min prior to the start of the first 5 min defeat. For no defeat control subjects, we bilaterally infused MDL 11,939 (17 mM, N =7) or vehicle (N=7) into the BLA 10 min prior to the first 5 min empty RA cage exposure. For drug injection, a 1μl syringe (Harvard Instruments) was connected to an injection needle via PE-20 polyethylene tubing. Injections took place over a 1 min period using a Harvard Syringe Pump (Harvard Instruments), and needles were left in place for 1 min after the infusion to allow drug diffusion. Microinjections were confirmed with movement of an air bubble in the tube, and any animal that did not receive successful bilateral injections was excluded from analysis. Subjects were tested for CD 24 h following social defeat and then returned to their home cage. Twenty-four hours following CD testing, subjects were tested in the open field arena immediately followed by the Y-maze test. Instead of all behavioral testing occurring 24 h after social defeat, we waited 48 h for open field and Y-maze testing in order to avoid possible carryover effects from CD testing.

2.8. Experiment 2

Experiment 2 was designed to test whether injection of a 5-HT2a receptor agonist into the BLA would increase the acquisition of CD. We bilaterally infused TCB-2 (8 mM, N = 9 or 80 mM, N = 11) or vehicle (N = 9) into the BLA 10 min prior to the start of a 5 min defeat. For no defeat control subjects, we infused TCB-2 (80 mM, N = 7) or vehicle (N = 8) into the BLA 10 min prior to a 5 min empty RA cage exposure. Animals received CD testing, open field testing, and Y-maze testing as described above.

2.9. Histology

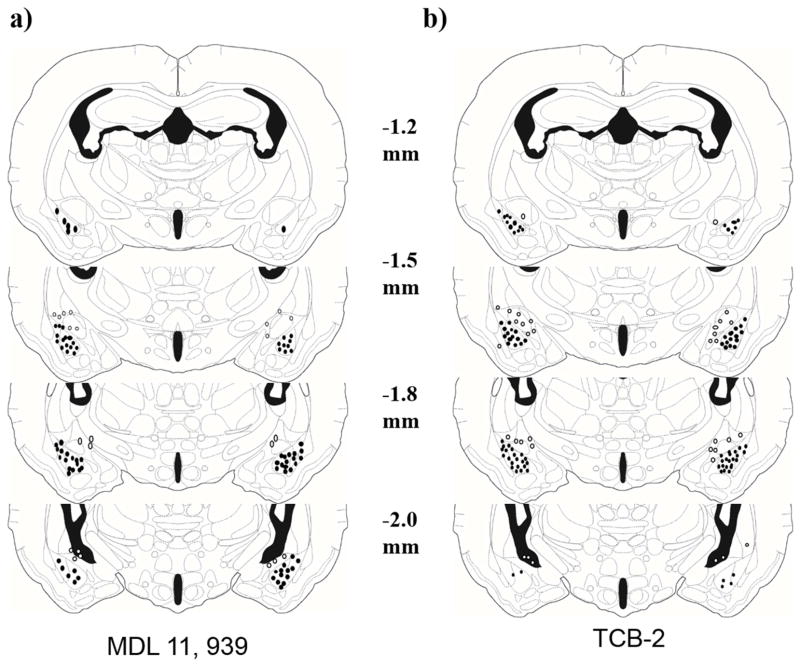

In experiments 1 & 2, animals were euthanized with an overdose of isoflurane immediately after Y-maze testing and infused with 200 nl of India ink into the BLA. Brains were removed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at -80°C. Brains were sliced at 30 μm on a cryostat, and sections were stained with neutral red and coverslipped. Sections were examined under a light microscope for evidence of ink in the BLA. Subjects with bilateral injection sites within 100 μm of the BLA were included in statistical analysis. Animals with unilateral or bilateral injection sites >100 μm from the BLA were analyzed as anatomical controls. The ink injections outside of the BLA were most often dorsal to the BLA, posterior to the BLA and in the central nucleus of the amygdala (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The location of BLA injection sites is shown using illustrations adapted from a hamster stereotaxic atlas (Morin and Wood, 2001). The distances shown for each illustration are relative to bregma and injection sites are shown for a) Experiement 1 and b) Experiment 2. Black circles indicate the approximate placement of injection sites within the BLA while open circles represent injection sites for anatomical controls.

2.10. Data Analysis

We performed two-way ANOVAs to investigate an interaction between defeat (2 levels) and drug treatment (2 levels) on CD, Y-maze and open field tests. For each behavioral test, we performed planned comparisons to investigate dose response relationships (one-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc tests) and non-selective drug effects in non-defeated controls (t-tests). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the α level was set at p ≤ 0.05. When the data violated the assumptions for parametric statistics, Mann-Whitney U tests were used for post-hoc comparisons.

3. Results

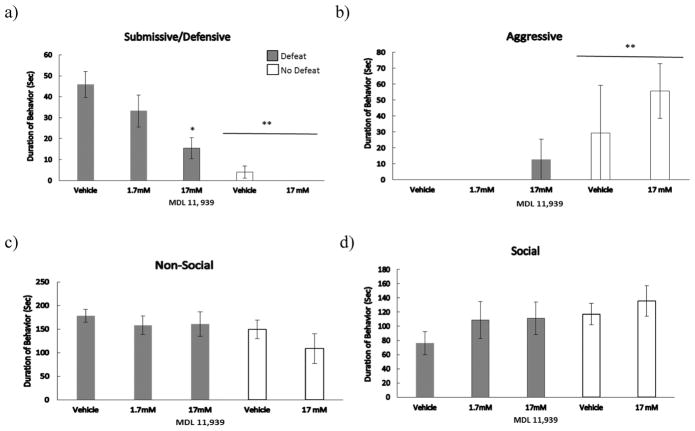

3.1. Experiment 1: MDL 11,939 effects on conditioned defeat

The injection of MDL 11,939 into the BLA prior to social defeat reduced the acquisition of CD (Fig. 2). We found a significant main effect of defeat experience (F(1,29) = 33.99, p = .001), and a significant defeat x drug dose interaction (F(1,29) = 7.20, p = .012) on the total duration of submissive/defensive behavior displayed at testing. Importantly, defeated individuals injected with 17 mM of MDL 11,939 displayed a lower duration of submissive/defensive behavior at testing when compared to defeated vehicle controls (F(2,25) = 5.70, p = .009; LSD, p = .002).

Figure 2.

Durations (mean ± SE) of a) submissive behavior, b) aggressive behavior, c) non-social behavior, and d) non-agonistic social behavior are shown for a 5-minute test with a novel, non-aggressive opponent. Defeated animals received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes before social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. *Indicates significant defeat x dose of MDL 11,939 interaction (p < .05). **Indicates a main effect of social defeat (p < .05).

We found a main effect of social defeat on aggressive behavior (F(1,29) = 4.88, p = .035). Specifically, no defeat control animals showed significantly more aggressive behavior at CD testing compared to defeated animals. A Mann-Whitney U test further confirmed a statistically significant difference between defeated animals and non-defeated animals (U(14,19) = 71, p = .035). We did not find a defeat experience x drug dose interaction for aggressive behavior. Additionally, there was a trend for a main effect of defeat experience on social (F(1,29) = 2.92, p = .098) and nonsocial (F(1,29) = 3.36, p = .077) behavior displayed at testing. Additionally, we did not find a drug effect in no defeat control animals for any category of behavior.

Eleven defeated animals received injections of MDL 11,939 or vehicle that were greater than 100 μm outside the BLA and were analyzed as anatomical controls. MDL 11,939 infused outside the BLA prior to social defeat did not significantly reduce submissive/defensive behavior at testing (p > 0.05; Vehicle: 44.7±11.6, N = 5; 1.7 mM: 50.3±7.9, N = 2; 17 mM: 51.3±9.7, N = 4).

To test whether the effect of MDL 11,939 on the acquisition of CD was related to differences in the quality of social defeat, we quantified the aggressive behavior of the RAs during social defeat. Drug treatment did not significantly alter the amount of aggression received compared to vehicle controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

MDL 11, 939 treatment did not alter social defeat experience (mean ± SE)

| Vehicle | 1.7 mM | 17 mM | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression (s) | 536.1 ± 41.6 | 478.4 ± 43.9 | 500.1 ± 24.3 | ns |

| Number of attacks | 17.4 ± 2.5 | 14.8 ± 1.7 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | ns |

Subjects received injection of MDL 11, 939 (1.7 mM or 17 mM) or vehicle into the basolateral amygdala 10 min prior to three, 5-minute social defeats. Total duration of aggressive behavior and number of attacks are shown for all three defeats combined. ns = not significant

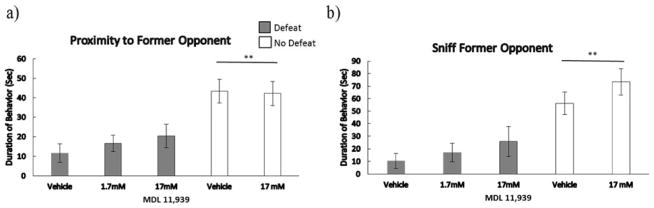

3.2. MDL 11,939 effects on Y-maze behavior

Injection of MDL 11,939 prior to social defeat did not significantly alter avoidance of a familiar aggressor in the Y-maze (Fig. 3). There was a main effect of defeat experience on proximity to the RA (F(1,28) = 24.04, p < .001), and the amount of time spent sniffing the RA (F(1,28) = 23.30, p < .001). Specifically, defeated subjects spent significantly less time in proximity to the RA and less time sniffing the RA compared to non-defeated controls. There was not a significant drug dose x defeat interaction, or a significant dose response relationship in defeated animals for either category of behavior. Also, we did not find a drug effect in non-defeated control animals in the Y-maze.

Figure 3.

Durations (means ± SE) of time spent in a) proximity to former opponent, and b) sniffing former opponent are shown for a 3-minute test in the Y-maze. Defeated animals received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes before social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. **Indicates a main effect of social defeat (p < .05).

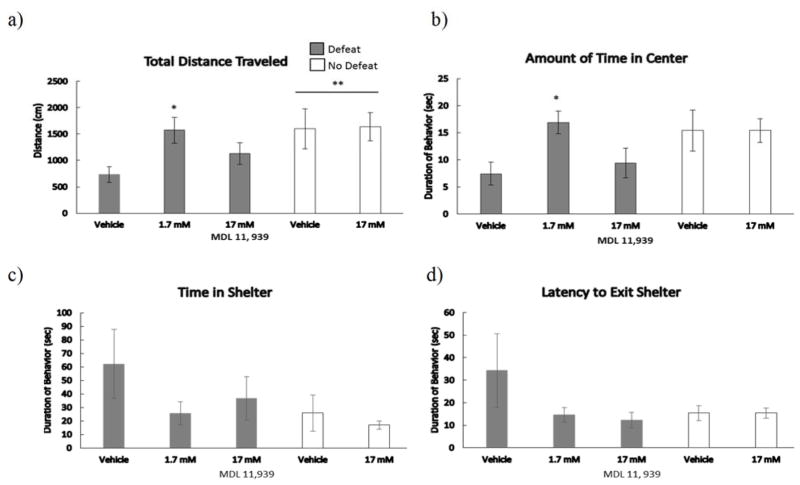

3.3. MDL 11,939 effects on open field behavior

Injection of MDL 11,939 reduced anxiety-like behavior in defeated animals (Fig. 4). We found a main effect of defeat experience on the total distance traveled, such that defeated subjects traveled a significantly shorter distance in the open field arena than non-defeated control subjects (F(1,28) = 7.80, p = .009). Furthermore, injection of MDL 11,939 (1.7 mM) significantly increased total distance traveled (F(2,23) = 4.67, p = .02, LSD p = .006) and the amount of time spent in the center of the open field (F(2,23) = 4.69, p = .02, LSD p = .007) compared to defeated vehicle animals. Animals treated with 17 mM MDL 11,939 were intermediate for total distance traveled and center time and did not significantly differ from animals injected with 1.7 mM or vehicle (p > .05). A main effect of defeat experience was not found in any other category of behavior. There was no significant effect of drug treatment in non-defeated control groups for any category of behavior in the open field.

Figure 4.

a) Total distance traveled and durations (mean ± SE) of b) time in center c) time in shelter, and d) latency to exit shelter are shown for a 5-minute open field test. Defeated animals received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes prior to social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of MDL 11,939 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. **Indicates a main effect of social defeat (p < .05). *Indicates significantly different than defeated, vehicle controls (p < .05).

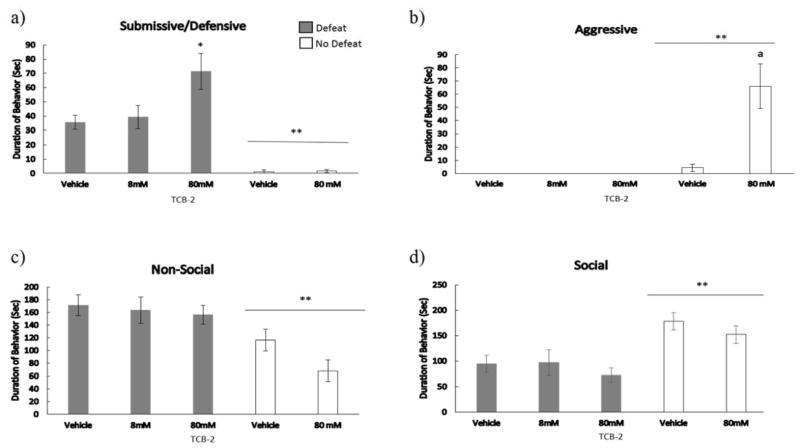

3.4. Experiment 2:TCB-2 effects on conditioned defeat

The injection of TCB-2 into the BLA prior to social defeat increased the acquisition of CD (Fig. 5). We found a significant main effect of defeat experience (F(1,31) = 34.8, p < .001), drug treatment (F(1,31) = 4.91, p = 0.034), and drug dose x defeat interaction (F(1,31) = 4.67, p = 0.039) on total duration of submissive/defensive behavior displayed at testing. Importantly, defeated individuals injected with 80 mM of TCB-2 displayed a greater duration of submissive/defensive behavior at testing compared to defeated vehicle controls (F(2,28) = 4.52, p = 0.021; LSD, p = 0.01).

Figure 5.

Durations (mean ± SE) of a) submissive behavior, b) aggressive behavior, c) non-social behavior, and d) non-agonistic social behavior are shown for a 5-minute test with a novel, non-aggressive opponent. Defeated animals received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes before social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. *Indicates significant defeat x dose of TCB-2 interaction (p < .05). **Indicates a main effect of social defeat (p < .05). Letter ‘a’ indicates significantly different than non-defeated, vehicle controls (p < .05).

We found a main effect of defeat experience (F(1,31) = 19.81, p < .001), drug treatment (F(1,31) = 15.2, p < .001), and a drug dose x defeat interaction (F(1,31) = 15.2, p < .001) for aggressive behavior displayed at testing. Specifically, no defeat control groups showed significantly more aggressive behavior at CD testing than did defeated animals. A Mann-Whitney U test further confirmed a statistically significant difference between defeated animals and non-defeated controls (U(15,20) = 69, p = .007). Also, drug treatment increased the duration of aggressive behavior in non-defeated animals compared to vehicle controls (T(13) = 15.0, p = 0.005). A Mann-Whitney U test further confirmed a statistically significant difference between non-defeated animals receiving drug treatment and non-defeated animals receiving vehicle (U(7,8) = 8, p = .029). We found a main effect of defeat experience on social (F(1,31) = 24.87, p < .001), and nonsocial (F(1,31) = 18.8, p < .001) behavior displayed at testing. Drug treatment did not significantly alter social or nonsocial behavior in non-defeated animals.

Twenty defeated animals received injections of TCB-2 or vehicle that were more than 100 μm outside the BLA and were analyzed as anatomical controls. TCB-2 infused outside the BLA prior to social defeat did not significantly increase submissive/defensive behavior at testing (p > 0.05; Vehicle: 52.2±10.8, N = 7; 8 mM: 60.9±23.9, N = 6; 80 mM: 33.4±7.4, N = 7).

To test whether the effect of TCB-2 on the acquisition of CD was related to differences in the quality of social defeat, we quantified the aggressive behavior of the RAs during social defeat. Drug treatment did not significantly alter the amount of aggression received compared to vehicle controls (Table 2).

Table 2.

TCB-2 treatment did not alter social defeat experience (mean ± SE)

| Vehicle | 8 mM | 80 mM | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression (s) | 182.5 ± 21.6 | 195.5 ± 49.6 | 171.7 ± 20.7 | ns |

| Number of attacks | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 0.96 | 7.0 ± 1.2 | ns |

Subjects received injection of TCB-2 (8 mM or 80 mM) or vehicle into basolateral amygdala 10 min prior to a single 5-min social defeat. ns = not significant

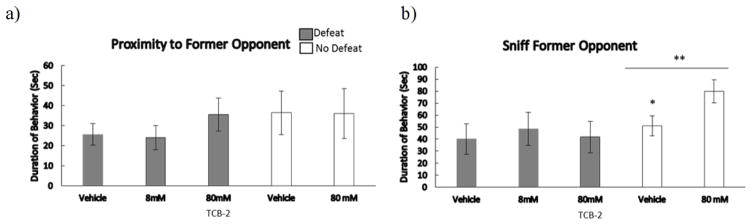

3.5. TCB-2 effects on Y-maze behavior

Injection of TCB-2 prior to social defeat did not significantly alter social avoidance to former opponents (Fig. 6). There was a main effect of defeat experience on the amount of time spent sniffing the RA (F(1,31) = 4.08, p = .05), which indicates that defeated animals spent less time near the RA engaged in olfactory investigation than did non-defeated animals. However, there was not a significant main effect of defeat experience on proximity to the RA. Surprisingly, in non-defeated animals drug treatment increased time spent sniffing the RA (T(13) = 0.19, p = 0.05). Drug treatment did not significantly alter proximity to the RA in non-defeated control subjects.

Figure 6.

Durations (means ± SE) of time spent in a) proximity to former opponent, and b) sniffing to former opponent for a 3-minute test in the Y-maze. Defeated animals received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes before social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. **Indicates a main effect of social defeat (p < .05). *Indicates significantly different than non-defeated animals injected with TCB-2 (p < .05).

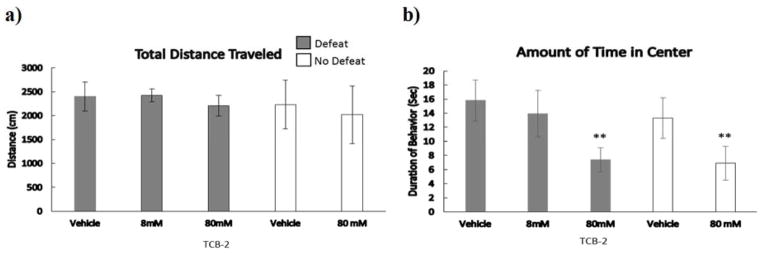

3.6. TCB-2 effects on open field behavior

Injection of TCB-2 prior to social defeat significantly reduced the amount of time animals spent in the center of the open field regardless of defeat experience (Figure 7; F(1,31) = 9.09, p = 0.005). There were no main effects of defeat experience or a drug dose x defeat interaction on the total distance traveled or amount of time animals spent in the center of the open field.

Figure 7.

a) Total distance traveled and b) duration of time in center are shown for a 5-minute open field test (mean ± SE). Defeated animals received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes prior to social defeat training. Likewise, non-defeated controls received an injection of TCB-2 or vehicle 10 minutes before exposure to a resident aggressor’s empty cage. **Indicates a significant main effect of drug treatment (p < .05).

4. Discussion

We have shown that injection of the 5-HT2a receptor antagonist MDL 11,939 prior to social defeat stress decreases the acquisition of CD, while injection of the 5-HT2a receptor agonist TCB-2 prior to social defeat increases the acquisition of CD. These results suggest that activation of 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA is both necessary and sufficient for the acquisition of CD. The effects of both drug treatments on the CD response appear to be localized to the BLA, as injections outside the BLA failed to alter CD. Because we have previously shown that systemic blockade of 5-HT2a receptors disrupts the acquisition, but not expression, of CD, our present results are consistent with the possibility that 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA specifically modulate the acquisition of CD (Harvey et al., 2012). Drug treatments did not alter submissive and defensive behavior in no defeat control animals or social and nonsocial behavior in defeated animals, which indicates that 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA specifically modulate stress-induced changes in agonistic behavior. However, injection of TCB-2 increased the duration of aggressive behavior displayed at testing in no defeat control animals. Although non-defeated vehicle animals showed very little submissive and defensive behavior they also showed less aggressive behavior than in other experiments (Morrison & Cooper, 2012), and less aggressive behavior than the non-defeated vehicle animals of the MDL 11,939 experiment. In contrast, non-defeated animals treated with TCB-2 attacked intruders quickly and sustained aggression throughout the testing session, which may indicate a more reactive or impulsive response. This is consistent with other research showing an increase in impulsivity following activation of 5-HT2a receptors. For example, administration of the 5-HT2a agonist DOI increased premature responding in a five-choice serial reaction time task, which is a well studied rodent model of attention and impulsivity (Koskinen et al., 2000).

Several lines of evidence support the notion that MDL 11,939 treatment reduced the acquisition of CD by blocking 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA. First, MDL 11,939 has greater selectivity for the 5-HT2a receptor than most other 5-HT2a receptor antagonists. Although MDL 11,939 has low nanomolar affinity for 5-HT2a receptors it has a 150-fold higher affinity for 5-HT2a receptors than for 5-HT2c receptors in the rabbit, and a 300-fold and 4000-fold higher affinity in rats and humans, respectively (Aloyo & Harvey, 2000; Pehek et al., 2006; Wainscott et al., 1996). Second, although comparable data are limited the doses used here are within the range used by other studies that administered MDL 11,939 into the medial prefrontal cortex (Bekinschtein et al., 2013). Third, we have previously shown that systemic administration of MDL 11,939 reduces the acquisition of CD at doses that have been shown to not affect 5-HT2c receptors (Aloyo & Harvey, 2000; Harvey et al., 2004; Harvey et al., 2012). Fourth, we have previously shown that peripheral administration of the non-selective 5-HT2 receptor agonist mCPP, which has high affinity for the 5-HT2c receptor fails to alter the acquisition of CD when given prior to social defeat, although it increases the expression of CD (Harvey et al., 2012). In sum, although we cannot rule out the possibility that a high dose of MDL 11,939 blocked 5-HT2c receptors, it appears that blockade of 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA accounts for the reduction in CD.

Previous research indicates that avoidance of former opponents reflects the formation of a fear-related memory for an acute social defeat (Lai et al., 2005; McCann & Huhman, 2012). In experiment 1, three, 5-min social defeat episodes increased avoidance of a former opponent 48 hours later. These results further validate the use of the Y-maze test for measuring memory of a social defeat experience, and show that social avoidance can last at least 48 hours after stress (Bader et al., 2014; Lai & Johnston, 2002). In experiment 2, a suboptimal 5-min social defeat led to a more modest and non-significant increase in social avoidance, which suggests that social avoidance may extinguish more rapidly following a very brief social defeat. TCB-2 treatment in non-defeated animals increased time spent in proximity to the RA compared to vehicle treatment, which again might indicate a more reactive response to a social stimulus. We found that injection of neither MDL 11,939 nor TCB-2 into the BLA prior to social defeat altered avoidance of familiar opponents in the Y-maze test, suggesting that 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA do not modulate the formation of a social defeat memory. While 5-HT2a receptor ligands can modulate the formation of memories for emotional events, they may act outside the BLA. In mice, systemic MDL 11,939 treatment has been shown to delay the extinction of conditioned fear and systemic TCB-2 treatment has been shown to facilitate it (Zhang et al., 2013). Also, pharmacological activation of 5-HT2a receptors with systemic drug treatment has been shown to facilitate the acquisition of eyeblink conditioning (Harvey, 2003; Romano et al., 2010). The contribution of 5-HT2a receptors to emotional memories may be related to NMDA receptor function, as 5-HT2a receptors enhance NMDA receptor sensitivity in the cortex (Arvanov et al., 1999) and increase presynaptic glutamate release in the lateral septum (Hasuo et al., 2002).

5-HT2a receptors have been shown to modulate the development of stress-related behavior. Systemic blockade of 5-HT2a receptors prevents the occurrence elevated acoustic startle following inescapable tailshock stress (Jiang et al., 2011). Also, 5-HT2a receptor blockade prevents the potentiation of anxiety-like behavior following predator stress (Adamec et al., 2004). We found that injection of the 5-HT2a receptor antagonist MDL 11,939 into the BLA prior to social defeat stress reduced anxiety-like behavior 48 hours later in an open field test, as indicated by increased total distance traveled and increased amount of time spent in the center of the arena. Social stress has been shown to reduce locomotion in an open-field (Bader et al., 2014; Meerlo et al., 1996; Raab et al., 1986), and anxiolytic drugs such as diazepam have been shown to reverse the stress-induced reduction in locomotion (Carli et al., 1989). These findings suggest that reduced locomotion as well as decreased center-time in an open-field test indicate anxiety-like behavior following social defeat. Compared to defeated vehicle control animals, defeat-induced anxiety-like behavior was reduced only by the lower dose of MDL 11,939 (1.7 mM). Because CD was not reduced by 1.7 mM of MDL 11,939, it suggests that open field behavior may be more sensitive to the effects of 5-HT2a receptor blockade than the CD response. Also, nonselective binding of MDL 11,939 at 5-HT2c receptors could account for the u-shaped dose response curve in the open field test.

We found that injection of TCB-2 into the BLA prior to social defeat decreased the amount of time spent in the center of the open field, but did not alter total distance traveled. This complex effect of TCB-2 on anxiety-like behavior occurred regardless of defeat experience. Once again, we attribute the effect of TCB-2 on reduced time in the center to the possibility that 5-HT2a receptor activation within the BLA could lead to impulsive, anxious behavior regardless of whether or not the animal has experienced a prior stressor. Furthermore, increased reactivity in drug-treated animals could increase locomotion and explain why TCB-2 treatment failed to alter total distance traveled. The suboptimal defeat experience does not appear to be a robust enough stressor to produce differences in anxiety-like behavior 48 hours following defeat because there was no effect of defeat on center time or total distance traveled in vehicle-treated animals. Furthermore, a comparison between vehicle-defeated animals in experiment 1 and vehicle-defeated animals in experiment 2 indicates the more robust social defeat in the first experiment has a more substantial effect on anxiety-like behavior. However, differences in anxiety between experiments 1 and 2 should be treated with caution because of the presence of a shelter for defensive withdrawal in experiment 1 only.

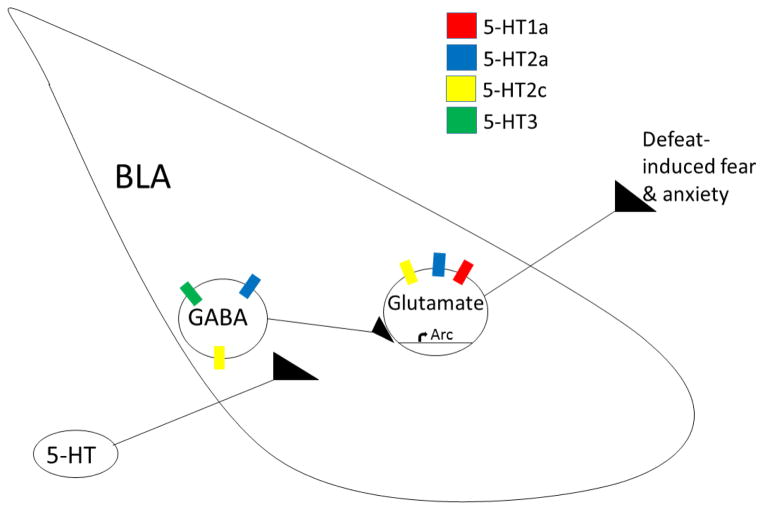

Several studies from our lab have shown that 5-HT is a key neurochemical modulating the acquisition and expression of CD and that the BLA is a critical neural substrate. Social defeat activates 5-HT neurons and downregulates 5-HT1a autoreceptors in the DRN of Syrian hamsters (Cooper et al., 2009). Also, inhibition of DRN 5-HT neurons by pharmacological activation of 5-HT1a autoreceptors reduces the acquisition and expression of CD (Cooper et al., 2008). Uncontrollable stress has been shown to increase 5-HT concentrations in the BLA (Amat et al., 1998), and the net effect of 5-HT efflux into the BLA depends on the activation of several 5-HT receptor subtypes (Figure 8). 5-HT1a receptors are predominantly located on glutamatergic pyramidal cells in the BLA where they generate hyperpolarization (Ogren et al., 2008; Palchaudhuri & Flügge, 2005; Stein et al., 2000). Injection of a 5-HT1a receptor agonist into the BLA has been shown to impair the acquisition of inhibitory avoidance and the expression of escape behavior in the elevated T-maze (Strauss et al., 2013). We have shown that pharmacological activation of 5-HT1a receptors in the BLA reduces acquisition and expression of CD (Morrison & Cooper, 2012). Also, systemic activation of 5-HT1a receptors prior to social defeat impairs fear-related memories of former opponents and reduces the number of defeat-induced Arc immunopositive cells in the BLA (Bader et al., 2014). These studies support the view that activation of BLA 5-HT1a receptors reduces Arc expression in pyramidal cells and thereby disrupts the formation of a defeat-related fear memory. 5-HT2c receptors are localized to both glutamatergic pyramidal cells and GABAergic interneurons in the BLA (Bombardi, 2014; Clemett et al., 2000). Activation of 5-HT2c receptors in the BLA facilitates the acquisition of inhibition avoidance in the elevated T-maze and increases anxiety in the light-dark transition test (Vicente & Zangrossi, 2014). Also, blockade of 5-HT2c receptors in the BLA prevents the expression of potentiated anxiety in animals exposed to inescapable tailshock (Christianson et al., 2010). Similarly, we have shown that systemic injection of a 5-HT2c receptor agonist increases the expression, but not acquisition, of the CD response (Harvey et al., 2012). In the amygdala 5-HT3 receptors are localized almost exclusively to GABAergic neurons (Mascagni & McDonald, 2007). 5-HT3 receptors in the amygdala have been shown to modulate anxiety-like behavior, although they do not alter the acquisition of conditioned fear (Gargiulo et al., 1996; Kondo et al., 2014). The role of BLA 5-HT3 receptors in the CD response has not been studied.

Figure 8.

A simplified neural circuit representing serotonergic modulation of CD. We propose that social defeat increases the activity of 5-HT neurons projecting to the BLA. Activation of 5-HT2c receptors on glutamatergic pyramidal cells should increase the expression of CD. In contrast, activation of 5-HT1a receptors should reduce the expression of CD, as well as reduce the acquisition of CD by disrupting Arc expression in pyramidal cells. Also, activation of 5-HT2a receptors on either GABAergic interneurons or BLA pyramidal neurons may lead to receptor desensitization after social defeat. Then, 5-HT influx at CD testing would lead to less 5-HT2a receptor-mediated inhibition and an increase in submissive and defensive behavior.

The current study indicates that the mechanism by which 5-HT2a receptors modulate CD differs from 5-HT1a and 5-HT2c receptors. 5-HT2a receptors are located on both BLA pyramidal neurons and PV-positive GABAergic interneurons, where their function is to directly and indirectly inhibit BLA pyramidal neurons (Bombardi, 2011; McCool et al., 2014; McDonald & Mascagni, 2007; Rainnie, 1999). Uncontrollable footshock has been shown to downregulate 5-HT2a receptor mRNA and protein levels and impair the ability of 5-HT2a receptors to facilitate GABAergic inhibition in the BLA (Jiang et al., 2009). Stress-related downregulation of 5-HT2a receptors should increase BLA excitability and increase fear and anxiety. In our study infusion of MDL 11,939 into the BLA may have reduced the acquisition of CD by preventing the defeat-induced downregulation of 5-HT2a receptors. Similarly, TCB-2 infusion into the BLA may have increased the acquisition of CD by facilitating 5-HT2a receptor downregulation. However, it is noteworthy that MDL 11,939 treatment did not modulate avoidance of former opponents in the Y-maze. These findings suggest that fear-related memories, which are likely dependent on neural plasticity within BLA pyramidal neurons, remain intact following blockade of BLA 5-HT2a receptors.

In sum, 5-HT1a receptor activation in the BLA modulates a fear component of the CD response perhaps by disrupting defeat-induced Arc expression. 5-HT2a receptors in the BLA modulate an anxiety component of the CD response perhaps by their defeat-induced downregulation. The overall effect of 5-HT efflux into the BLA depends on the balance of 5-HT activity at these receptor subtypes. These findings should be useful when considering serotonergic treatments that target fear and/or anxiety components of stress-related mental illness.

Highlights.

We investigated serotonergic modulation of fear and anxiety after social defeat.

5-HT2a receptor blockade in the BLA reduces the acquisition of conditioned defeat.

5-HT2a receptor activation in the BLA increases acquisition of conditioned defeat.

BLA 5-HT2a receptors alter defeat-induced anxiety but not defeat-related memories.

Acknowledgments

We thank our team of undergraduate students for their daily technical assistance, including Sonya Gross and Abigail Barnes. We also thank Debbie Floyd for her expert animal care. This work was supported by NIH grant R21 MH098190.

Abbreviations

- Arc

activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CD

conditioned defeat

- DRN

dorsal raphe nucleus

- i. p

intraperitoneal injection

- PV

parvalbumin

- RA

resident aggressor

- 5-HT

serotonin

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adamec R, Creamer K, Bartoszyk GD, Burton P. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of acute systemic injections of EMD 281014, a selective serotonin 2A receptor antagonist on anxiety induced by predator stress in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;504(1–2):79–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloyo VJ, Harvey JA. Antagonist binding at 5-HT 2A and 5-HT 2C receptors in the rabbit3: High correlation with the profile for the human receptors. 2000:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat J, Matus-Amat P, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Escapable and inescapable stress differentially alter extracellular levels of 5-HT in the basolateral amygdala of the rat. Brain Research. 1998;812(1–2):113–20. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanov VL, Liang X, Magro P, Roberts R, Wang RY. A pre- and postsynaptic modulatory action of 5-HT and the 5-HT2A, 2C receptor agonist DOB on NMDA-evoked responses in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11(8):2917–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader LR, Carboni JD, Burleson C, Cooper MA. 5-HT1A receptor activation reduces fear-related behavior following social defeat in Syrian hamsters. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein P, Renner MC, Gonzalez MC, Weisstaub N. Role of medial prefrontal cortex serotonin 2A receptors in the control of retrieval of recognition memory in rats. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(40):15716–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2087-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard DC, Spencer RL, Weiss SM, Blanchard RJ, McEwen B, Sakai RR. Visible burrow system as a model of chronic social stress: behavioral and neuroendocrine correlates. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20(2):117–34. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)e0045-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi C. Distribution of 5-HT2A receptor immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex and colocalization with γ-aminobutyric acid ☆. Brain Research. 2011;1370:112–128. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombardi C. Neuronal localization of the 5-HT2 receptor family in the amygdaloid complex. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2014;5(April):68. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli M, Prontera C, Samanin R. Effect of 5-HT1a agonists on stress-induced deficit in open field locomotor activity of rats: Evidence that this model identifies anxiolytic-like activity. Neuropharmacology. 1989;28(5) doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(89)90081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JP, Ragole T, Amat J, Greenwood BN, Strong PV, Paul ED, Maier SF. 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptors in the basolateral amygdala are involved in the expression of anxiety after uncontrollable traumatic stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemett DA, Punhani T, Duxon MS, Fone KCF, Blackburn TP. Immunohistochemical localisation of the 5-HT 2C receptor protein in the rat. CNS. 2000;39:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, Grober MS, Nicholas CR, Huhman KL. Aggressive encounters alter the activation of serotonergic neurons and the expression of 5-HT1A mRNA in the hamster dorsal raphe nucleus. Neuroscience. 2009;161(3):680–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA, McIntyre KE, Huhman KL. Activation of 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus reduces the behavioral consequences of social defeat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(9):1236–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, Kim JJ, Yipp J, De Oca B. Differential effects of the N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate on acquisition of fear of auditory and contextual cues. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108(2):235–40. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo PA, Viana MB, Graeff FG, de Souza Silva MA, Tomaz C. Effects on Anxiety and Memory of Systemic and Intra-Amygdala Injection of 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonist BRL 46470A. Neuropsychobiology. 1996;33:189–195. doi: 10.1159/000119276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale MW, Johnson PL, Westerman AM, Abrams JK, Shekhar A, Lowry Ca. Multiple anxiogenic drugs recruit a parvalbumin-containing subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons in the basolateral amygdala. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2010;34(7):1285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey BH, Naciti C, Brand L, Stein DJ. Serotonin and stress: protective or malevolent actions in the biobehavioral response to repeated trauma? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1032:267–72. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA. Role of the serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor in learning. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2003;10(5):355–62. doi: 10.1101/lm.60803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey ML, Swallows CL, Cooper Ma. A double dissociation in the effects of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors on the acquisition and expression of conditioned defeat in Syrian hamsters. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;126(4):530–7. doi: 10.1037/a0029047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasuo H, Matsuoka T, Akasu T. Activation of presynaptic 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors facilitates excitatory synaptic transmission via protein kinase C in the dorsolateral septal nucleus. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22(17):7509–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07509.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CH, Kuo MT, Lai WS. Characterization of behavioural responses in different test contexts after a single social defeat in male golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) Behavioural Processes. 2011;86(1):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhman KL, Solomon MB, Janicki M, Harmon AC, Lin SM, Israel JE, Jasnow AM. Conditioned defeat in male and female syrian hamsters. Hormones and Behavior. 2003;44(3):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow AM, Shi C, Israel JE, Davis M, Huhman KL. Memory of social defeat is facilitated by cAMP response element-binding protein overexpression in the amygdala. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(4):1125–30. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.4.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Xing G, Yang C, Verma A, Zhang L, Li H. Stress impairs 5-HT2A receptor-mediated serotonergic facilitation of GABA release in juvenile rat basolateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology3: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):410–23. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zhang Z, Zhang S, Gamble EH, Jia M, Ursano RJ, Li H. 5-HT2A receptor antagonism by MDL 11,939 during inescapable stress prevents subsequent exaggeration of acoustic startle response and reduced body weight in rats. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2011;25(2):289–97. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josselyn Sa, Shi C, Carlezon Wa, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Davis M. Long-term memory is facilitated by cAMP response element-binding protein overexpression in the amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2001;21(7):2404–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Casual Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and the Onset of Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999 Jun;:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Nakamura Y, Ishida Y, Yamada T, Shimada S. The 5-HT3A receptor is essential for fear extinction. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2014;21(1):1–4. doi: 10.1101/lm.032193.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen T, Ruotsalainen S, Puumala T, Lappalainen R. Activation of 5-HT 2A receptors impairs response control of rats in a five-choice serial reaction time task. 2000;39:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CJ, Tang HS, Tsay CJ, Lin SK, Hu WH, Chen CC. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among bereaved survivors of a disastrous earthquake in taiwan. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC) 2003;54(2):249–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WS, Johnston RE. Individual recognition after fighting by golden hamsters: a new method. Physiology & Behavior. 2002;76(2):225–39. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai WS, Ramiro LLR, Yu Ha, Johnston RE. Recognition of familiar individuals in golden hamsters: a new method and functional neuroanatomy. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(49):11239–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2124-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux J. The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2003;23(4–5):727–38. doi: 10.1023/A:1025048802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez J, Akil H, Watson SJ. Neural Circuits Mediating Stress. Role of Biological and Psychological Factors in Early Development and Their Impact on Adult Life. 1999;3223(99) [Google Scholar]

- Maddox S, Schafe G. NIH Public Access. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(19):7073–7082. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1120-11.2011.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Watkins LR. Stressor controllability and learned helplessness: the roles of the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin, and corticotropin-releasing factor. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2005;29(4–5):829–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Huhman KL. Is the medial amygdala part of the neural circuit modulating conditioned defeat in Syrian hamsters? Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2008;15(1):6–12. doi: 10.1101/lm.768208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascagni F, McDonald aJ. A novel subpopulation of 5-HT type 3A receptor subunit immunoreactive interneurons in the rat basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2007;144(3):1015–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann KE, Huhman KL. The effect of escapable versus inescapable social defeat on conditioned defeat and social recognition in Syrian hamsters. Physiology & Behavior. 2012;105(2):493–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool Ba, Christian DT, Fetzer Ja, Chappell AM. Lateral/basolateral amygdala serotonin type-2 receptors modulate operant self-administration of a sweetened ethanol solution via inhibition of principal neuron activity. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2014;8(January):5. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A, Mascagni F. Neuronal localization of 5-HT type 2A receptor immunoreactivity in the rat basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2007;146(1):306–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerlo P, Overkamp GJF, Benning MA, Koolhaas JM, Van Den Hoofdakker RH. Long-Term Changes in Open Field Behaviour Following a Single Social Defeat in Rats Can Be Reversed by Sleep Deprivation. 1996;60(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison KE, Cooper MA. A role for 5-HT1A receptors in the basolateral amygdala in the development of conditioned defeat in Syrian hamsters. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2012;100(3):592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13(10):1161–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren SO, Eriksson TM, Elvander-Tottie E, D’Addario C, Ekström JC, Svenningsson P, Stiedl O. The role of 5-HT(1A) receptors in learning and memory. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;195(1):54–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palchaudhuri M, Flügge G. 5-HT1A receptor expression in pyramidal neurons of cortical and limbic brain regions. Cell and Tissue Research. 2005;321(2):159–72. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehek EA, Nocjar C, Roth BL, Byrd Ta, Mabrouk OS. Evidence for the preferential involvement of 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in stress- and drug-induced dopamine release in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology3: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(2):265–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploski JE, Pierre VJ, Smucny J, Park K, Monsey MS, Overeem Ka, Schafe GE. The activity-regulated cytoskeletal-associated protein (Arc/Arg3.1) is required for memory consolidation of pavlovian fear conditioning in the lateral amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28(47):12383–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1662-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potegal M, Huhman K, Moore T, Meyerhoff J. Conditioned defeat in the Syrian golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus) Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1993;60(2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90159-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab A, Dantzer R, Michaud B, Mormede P, Taghzouti K, Moal HSANDMLE. Behavioural, Physiological and Immunological Consequences of Social Status and Aggression in Chronically Coexisting Resident-Intruder Dyads of Male Rats. 1986;36:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainnie DG. Serotonergic modulation of neurotransmission in the rat basolateral amygdala. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82(1):69–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risbrough VB, Stein MB. Role of corticotropin releasing factor in anxiety disorders: a translational research perspective. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50(4):550–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman E, Arborelius L. Male but not female Wistar rats show increased anxiety-like behaviour in response to bright light in the defensive withdrawal test. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;202(2):303–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano AG, Quinn JL, Li L, Dave KD, Schindler Ea, Aloyo VJ, Harvey Ja. Intrahippocampal LSD accelerates learning and desensitizes the 5-HT(2A) receptor in the rabbit, Romano et al. Psychopharmacology. 2010;212(3):441–8. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of auditory pavlovian fear conditioning requires protein synthesis and protein kinase A in the amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience3: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2000;20(18):RC96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-j0003.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C, Davidowa H, Albrecht D. 5-HT(1A) receptor-mediated inhibition and 5-HT(2) as well as 5-HT(3) receptor-mediated excitation in different subdivisions of the rat amygdala. Synapse (New York, NY) 2000;38(3):328–37. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001201)38:3<328::AID-SYN12>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss CVDA, Vicente MA, Zangrossi H. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in the rat basolateral amygdala induces both anxiolytic and antipanic-like effects. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;246:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth I, Neumann ID. Animal models of social avoidance and social fear. Cell and Tissue Research. 2013;354(1):107–18. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1636-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten E, Bremner JD. Circuits and systems in stress. II. Applications to neurobiology and treatment in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;16(1):14–38. doi: 10.1002/da.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente MA, Zangrossi H. Involvement of 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A receptors of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala in the anxiolytic effect of chronic antidepressant treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieweg WVR, Julius Da, Fernandez A, Beatty-Brooks M, Hettema JM, Pandurangi AK. Posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(5):383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainscott B, Nelson L, Lilly E. Pharmacologic Characterization Receptor3: Differences of the Human Evidence for Species. 1996:720–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Ásgeirsdóttir HN, Cohen SJ, Munchow AH, Barrera MP, Stackman RW. Stimulation of serotonin 2A receptors facilitates consolidation and extinction of fear memory in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;64:403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]