Abstract

The rewarding properties of some abused drugs are thought to reside in their ability to increase striatal dopamine levels. Similar increases have been shown in response to expectation of a positive drug effect. The actions of opioid drugs on striatal dopamine release are less well characterized. We examined whether heroin and the expectation of heroin reward increases striatal dopamine levels in human opioid addiction. Ten opioid-dependent participants maintained on either methadone or buprenorphine underwent [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography imaging. Opioid-dependent participants were scanned three times, receiving reward from 50-mg intravenous heroin (diamorphine; pharmaceutical heroin) during the first scan to generate expectation of the same reward at the second scan, during which they only received 0.1-mg intravenous heroin. There was no heroin injection during the third scan. Intravenous 50-mg heroin during the first scan induced pronounced effects leading to high levels of expectation at the second scan. There was no detectable increase in striatal dopamine levels to either heroin reward or expectation of reward. We believe this is the first human study to examine whether expectation of heroin reward increases striatal dopamine levels in opioid addiction. The absence of detectable increased dopamine levels to both the expectation and delivery of a heroin-related reward may have been due to the impact of substitute medication. It does however contrast with the changes seen in abstinent stimulant users, suggesting that striatal dopamine release alone may not play such a pivotal role in opioid-maintained individuals.

Keywords: Addiction, dopamine, expectation, heroin, opioid, PET

Introduction

The euphoric effect of stimulants has been shown to correlate with striatal dopamine release, and increases in dopamine have also been reported with alcohol, nicotine and cannabis (Volkow et al. 2011), but not consistently nor always associated with a subjective ‘high’ (Boileau et al. 2003; Montgomery et al. 2007; Stokes et al. 2009). In contrast, we previously found that 50-mg intravenous heroin, despite producing a very profound ‘high’, did not increase dopamine levels in methadone-maintained opioid-dependent individuals (Daglish et al. 2008). However, there is evidence in primates that dopamine cell firing appears to be associated with the expectation, rather than the receipt of reward (see Schultz 2010). Consistent with this in humans, expectation of methylphenidate has been shown to result in larger increases in brain metabolism in cocaine-dependent individuals, than when it is unexpected (Volkow et al. 2003). Also dopamine release in response to cocaine cues has been demonstrated in the dorsal striatum of individuals abusing cocaine (Volkow et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2006). Increased dopamine levels in the right putamen have also been reported to heroin-related cues in abstinent opioid-dependent individuals (Zijlstra et al. 2008). Such increases in the dorsal striatum are consistent with its role in habit learning and compulsive drug use (Everitt & Robbins 2005). These increases in cue-induced dopamine levels occur despite chronic drug abuse being associated with a hypodopaminergic state (Volkow et al. 2010).

It is important to characterize the role of dopamine in the various drugs of abuse, because it has been argued that opioid and psychostimulant addiction are neurobiologically distinct with important implications for theories of addiction and its treatment (Badiani et al. 2011). We therefore developed our previous protocol using [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (Daglish et al. 2008), to further test two hypotheses in opioid-dependent participants: (1) striatal dopamine levels would increase with expectation of heroin reward and (2) striatal dopamine levels would increase after intravenous heroin.

Materials and Methods

The study received approval from the Bath National Health Service Research Ethics Committee and the Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, UK. All participants gave written informed consent prior to study procedures. Male participants aged over 18 years old, who met the Fourth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria for opioid dependence, currently maintained on methadone (≥30 mg/day) or buprenorphine (<8 mg/day), were recruited from outpatient addiction services. Participants were not dependent on or misusing any other substance other than nicotine, or had a history of clinically significant psychiatric or medical illness, or were taking other psychotropic medication. All participants provided a negative urinalysis for illicit substances of abuse before each scan.

PET data acquisition

Each participant underwent three [11C]raclopride PET scans, separated by at least 1 week determined by scanner availability [mean ± standard deviation (SD) interval between first and second PET scans 14.0 ± 7.6 days; mean ± SD interval between second and third PET scans 12.5 ± 7.4 days]. Each PET scan occurred at a similar time of day and participants were over 24 hours after their last dose of methadone or buprenorphine, which they deferred taking until after the scan. At the first (‘reward’) PET scan, participants were told they would receive an injection of pharmaceutical heroin (diamorphine; subsequently referred to as heroin), although the dose was undisclosed as in our previous study (Daglish et al. 2008). Fifty milligrams of heroin in 5 ml of water was given intravenously, 55 minutes into the 100-minute scan. At their second (‘expectation’) PET scan, participants were also told that they would receive a heroin injection during the scan and again the dose was undisclosed. On this occasion, however, participants were given a low and undetectable dose of 0.1-mg heroin in 5 ml of water intravenously, 55 minutes into the 100-minute scan. In the reward and expectation scans we heightened their expectation of heroin reward by giving time checks every 10 minutes and counted down the last 30 seconds, and using a webcam so participants could see the injection, including the salient blood flashback. At their third (‘no-drug’) PET scan participants were told they would not receive an injection of heroin. This scan was used to measure [11C]raclopride binding, free from any expectation or rewarding effects. All participants underwent T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on a separate day, with a Philips 1.5T Gyroscan Intera scanner (Philips, Best, The Netherlands) to produce structural images for reference.

All PET scans were conducted using an ECAT HR+ 962 scanner (CTI/Siemens, Knoxville, TN, USA), with an axial field of view of 15.5 cm. A 10-minute transmission scan was acquired prior to each emission scan to correct for tissue attenuation. Dynamic emission scans were acquired in three-dimensional mode using a standard acquisition protocol (38 frames over 100 minutes; Stokes et al. 2010). Each participant received 240 MBq of [11C]raclopride administered as an initial intravenous bolus (922 ml/hour for 60 seconds) followed by a constant infusion (8.8 ml/hour) for the remainder of the scan (Watabe et al. 2000). We used a bolus infusion of [11C]raclopride to deal with potential limitations of our previous bolus protocol such as timing of heroin and [11C]raclopride injection and minimize confounds such as drug-related blood flow effects by establishing a state of constant equilibrium (Carson et al. 1997).

Subjective and physiological measures

Before each [11C]raclopride PET scan, participants completed Beck's Depressive Inventory (BDI; Beck et al. 1961) and Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SSAI, STAI; Spielberger et al. 1983). Visual analogue scales (VAS; 100 points) were used to rate ‘high’, ‘rush’, ‘gouched’ (local slang for opioid intoxication), ‘urge and craving’ (to use heroin) and ‘withdrawal’ during their [11C]raclopride PET scans. Ratings were collected at baseline, 6 minutes prior to the start of the scan, and at 6, 16, 28, 38, 48, 63, 73, 83, 93 and 5 minutes post-scan. Opioid withdrawal was also assessed before and after each scan using a Modified Himmelsbach Opiate Withdrawal Scale (Law et al. 1997). Levels of expectation were measured using VAS, asking participants how good they expected the scan and heroin injection to be immediately before the scan and how good it had been immediately after the scan. They were also asked what equivalent value of street heroin they had been given after reward and expectation scans.

To objectively assess the effects of heroin on the brain we used our standard protocol measuring saccadic eye movements immediately before each VAS data collection point (Wilson et al. 1993). The impact of heroin on respiratory depression was monitored with pulse oximetry. Blood for methadone plasma concentrations was taken immediately before each scan and quantified using a modified liquid–liquid extraction followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Paterson, Cordero & Burlinson 2004).

PET data analysis

All dynamic scans were motion corrected using frame-by-frame realignment in Piwave 7.0 (in-house software; Imperial College London, London, UK) running in Matlab® (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA; Montgomery et al. 2006). The resultant dynamic frames were processed with receptor parametric mapping (RPM) to generate an add-image (Gunn et al. 1997), which was a weighted sum of all 38 frames. MRIs were co-registered to the individual add-images using Statistical Parametric Mapping 5 (SPM5; Functional Imaging Laboratory, University College London, UK) and then normalized into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space (International Consortium for Brain Mapping) using bias-corrected segmentation in SPM5.

For the region of interest (ROI) analysis, the inverse deformation parameters obtained from the segmentation process were applied to a functional striatal atlas (Martinez et al. 2003). Striatal and cerebellar ROIs were defined using an atlas composed of the three functional subdivisions of the striatum: limbic (ventral), associative (pre-commissural dorsal putamen, pre-commissural dorsal caudate and post-commissural dorsal caudate) and sensorimotor striatum (post-commissural putamen) and cerebellum. The individual deformed atlases were used to sample the add-images described earlier using Analyze software (http://www.analyzedirect.com;). Accounting for radioactive decay, we previously reported [11C]raclopride equilibrium stability of 0.06% per minute over the equilibrium period using this bolus infusion protocol (Stokes et al. 2009).

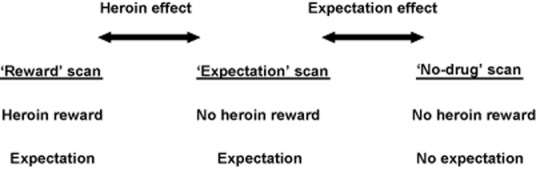

Binding potential (BPND) values for [11C]raclopride in each striatal region were calculated as the ratio of striatal counts to cerebellar counts, minus 1, over the steady-state time periods (Lammertsma & Hume 1996). Frames 19–22 (35.5–55.5 minutes) corresponded to the pre-heroin injection equilibrium period and were used to generate ‘early’ steady-state phase add-images. Frames 25–38 (57.5–100.5 minutes) corresponded to the post-heroin injection equilibrium period and were used to generate ‘late’ steady-state phase add-images (Egerton et al. 2009). The study was designed so that any difference in [11C]raclopride binding between reward and expectation scans would be due to the effect of heroin, while differences in [11C]raclopride binding between expectation and no-drug scans would be due to the effect of expectation (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Drug and expectation factors present in each participants' scan

Exploratory voxelwise analysis was also undertaken using image algebra within SPM5 running in Matlab® (The MathWorks Inc.) to create parametric BPND maps. The steady-state add-image voxels were divided by the cerebellar counts minus 1. Percentage increase images between the early and late phase BPND maps were calculated for reward, expectation and no-drug scans using the equation  , where i1 is the early phase parametric image and i2 is the late phase parametric image. The resulting images were normalized to a [11C]raclopride template image in MNI space and smoothed using a 6 mm3 full width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel.

, where i1 is the early phase parametric image and i2 is the late phase parametric image. The resulting images were normalized to a [11C]raclopride template image in MNI space and smoothed using a 6 mm3 full width at half-maximum Gaussian kernel.

Statistical analysis

All statistical comparisons, apart from voxelwise analyses, were performed using SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All t-tests were two-tailed. Paired samples t-tests were used to compare subjective measures. Correlations between parametric data were assessed using Pearson's product–moment correlation coefficient. Differences in early and late steady-state phases within and between different scans were investigated using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with striatal region as a within-subject factor. Heterogeneity of covariance was tested with the Mauchly sphericity test and degrees of freedom modified using the Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment, where appropriate.

Voxelwise analyses were performed within SPM5 using an explicit striatal mask. Differences in early and late steady-state phases within and between different scans were compared using a paired t-test. A height threshold of P < 0.001 and volume-corrected cluster threshold of P < 0.05 were used for statistical significance (Stokes et al. 2009).

Results

Eleven opioid-dependent individuals started the three-scan protocol; however, one withdrew after the first scan due to subsequent failure of [11C]raclopride synthesis, leaving 10 who completed all three [11C]raclopride PET scans. The mean ± SD participant age was 37.8 ± 9.0 years. Nine participants were receiving methadone maintenance (mean ± SD daily dose 50.5 ± 25.2 mg) and one buprenorphine maintenance (5 mg/day). The mean ± SD length of prior opioid use was 13.9 ± 6.3 years. All participants were tobacco smokers and had last smoked cannabis more than 2 months prior to imaging. Six participants had no recent alcohol consumption, with the remaining participants consuming 8–18 units (64–144 g) of alcohol per week. Occasional stimulant use was reported by all participants, with last use over 2 years previously for all but two (2 months, 6 months). Mean ± SD BDI and SSAI scores did not differ significantly between scans and were as follows: reward scan (BDI 12.9 ± 9.5; SSAI 39.1 ± 12.8), expectation scan (BDI 12.6 ± 10.1; SSAI 34.5 ± 8.8) and no-drug scan (BDI 12.9 ± 10.9; SSAI 33.3 ± 9.7). The mean ± SD STAI score was 43.7 ± 11.3. These scores reflect only mild symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Subjective and physiological measures

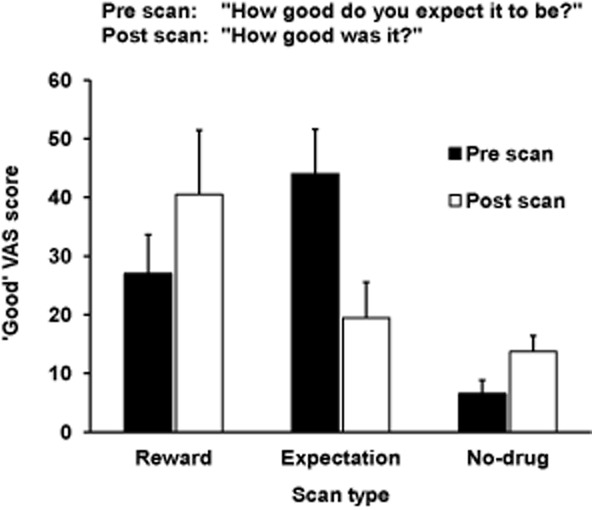

The key experimental objective of inducing expectation for heroin reward in both reward and expectation scans was achieved (Fig. 2). Expectation levels as measured by mean pre-scan ‘good’ VAS scores were higher for the expectation scan than the reward scan (t9 = −2.18, P = 0.057). A significant difference was seen between mean pre-scan ‘good’ VAS scores of reward and no-drug scans (t9 = 3.11, P = 0.013), and of expectation and no-drug scans (t9 = 5.61, P < 0.001). All participants in the reward scan and 7 of 10 participants in the expectation scan believed they had experienced effects of heroin after the injection. The mean ± SD estimated equivalent value of street heroin received was £18.00 ± 13.20 in the reward scan and £5.50 ± 4.40 in the expectation scan (£10 buys approximately 0.2-g heroin).

Figure 2.

Mean ‘good’ visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, pre and post each scan. Standard error bars shown

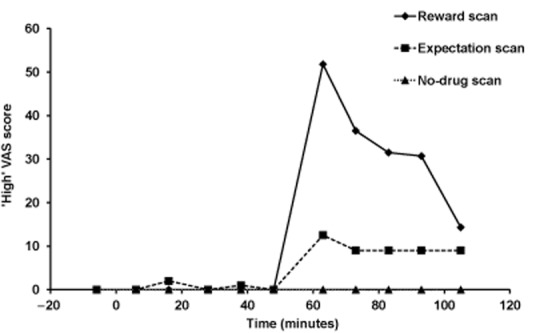

In the reward scan following heroin injection, there were pronounced and significant increases in VAS scores for the positive effects of heroin (Fig. 3) such as high (mean ± SD change 51.8 ± 30.6, t9 = 5.36, P < 0.001), rush (47.8 ± 37.7, t9 = 4.01, P = 0.003) and gouched (29.0 ± 31.8, t9 = 2.89, P = 0.018). There were smaller and non-significant increases seen in these VAS scores in the expectation scan and in the no-drug scan, all participants scored zero throughout. During all scans ratings of withdrawal and urge and craving to use heroin were low and did not change significantly as a result of any interventions.

Figure 3.

Mean ‘high’ visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, plotted against time for each scan

The predicted slowing and impairment of saccadic eye movements was observed in the reward scan, but not in the expectation scan consistent with our previous study (Daglish et al. 2008). Oxygen saturation levels remained stable and within normal limits in all participants throughout the expectation and no-drug scans, but fell in the reward scan to a mean ± SD minimum level of 83.3% ± 10.3.There was no significant difference seen in pre-scan methadone plasma levels between the three scans (mean ± SD reward scan 255.6 ± 201.4 ng/ml; expectation scan 228.9 ± 229.4 ng/ml; no-drug scan 210.0 ± 160.4 ng/ml; ANOVA, F2,14 = 0.37, P = 0.70).

[11C]raclopride PET

No significant effect of expectation on [11C]raclopride BPND in any striatal ROI was found in two comparisons: [11C]raclopride BPND in early and late steady-state phases within the expectation scan (ANOVA F1,9 = 0.08, P = 0.78), and between early and late steady-state phases in the expectation and no-drug scans (ANOVA F1,9 = 0.32, P = 0.59). We also found no significant effect from 50 mg of heroin on [11C]raclopride BPND values in any striatal ROI. Two comparisons were undertaken: [11C]raclopride BPND in early and late steady-state phases within the reward scan (ANOVA F1,9 = 0.06, P = 0.82), and between early and late steady-state phases in the reward and expectation scans (ANOVA F1,9 = 0.11, P = 0.75). In addition there were no significant correlations between VAS high scores and [11C]raclopride BPND values in any striatal region. Table 1 shows mean BPND values in each of the scans.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation [11C]raclopride binding potential in each scan

| Striatal region | Reward scan | Expectation scan | No-drug scan | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | Early | Late | Early | Late | |

| Sensorimotor | ||||||

| Left | 2.44 ± 0.33 | 2.45 ± 0.28 | 2.47 ± 0.26 | 2.48 ± 0.27 | 2.57 ± 0.31 | 2.54 ± 0.36 |

| Right | 2.32 ± 0.38 | 2.34 ± 0.33 | 2.44 ± 0.30 | 2.44 ± 0.30 | 2.58 ± 0.36 | 2.56 ± 0.39 |

| Associative | ||||||

| Left | 1.97 ± 0.33 | 1.96 ± 0.29 | 2.02 ± 0.30 | 1.99 ± 0.27 | 2.19 ± 0.32 | 2.11 ± 0.33 |

| Right | 2.19 ± 0.31 | 2.21 ± 0.29 | 2.25 ± 0.29 | 2.22 ± 0.28 | 2.37 ± 0.33 | 2.31 ± 0.35 |

| Limbic | ||||||

| Left | 1.95 ± 0.31 | 1.96 ± 0.26 | 2.10 ± 0.20 | 2.11 ± 0.20 | 2.26 ± 0.37 | 2.18 ± 0.36 |

| Right | 1.91 ± 0.29 | 1.90 ± 0.22 | 1.90 ± 0.26 | 1.90 ± 0.28 | 1.99 ± 0.32 | 2.01 ± 0.25 |

Early = early steady-state phase; Late = late steady-state phase.

Our exploratory voxelwise analysis generally confirmed the ROI analysis with no significant differences found in early and late steady-state phases between reward and expectation scans or between expectation and no-drug scans. There were small clusters in the reward and expectation scans in which BPND increased significantly from early to late steady-state phases (Table 2); no significant decreases were seen. There were no significant increases or decreases in BPND within the no-drug scan.

Table 2.

Areas of significant increase in [11C]raclopride binding potential from early to late steady-state phases within reward and expectation scans, identified in the exploratory voxelwise analysis

| Striatal region | Cluster sizea (voxels) | Coordinatesc (x, y, z) | t value | Correctedb P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward scan | ||||

| L associative/limbic | 43 | −12, 22, −6 | 9.42 | < 0.001 |

| L limbic | 15 | −24, 8, −12 | 6.89 | 0.008 |

| Expectation scan | ||||

| R sensorimotor | 38 | 28, −4, −8 | 12.02 | < 0.001 |

| L limbic | 35 | −24, 2, −12 | 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| L limbic | 26 | −18, 20, −8 | 8.25 | 0.001 |

| R associative | 13 | 18, 20, 8 | 7.51 | 0.021 |

Cluster sizes correspond to number of voxels of dimension 2 mm3.

P values were after correction for striatal volume.

The Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates, corrected P and t values are for the voxel in each cluster containing the peak effect size. L = left; R = right.

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge to examine whether the expectation of heroin reward increases striatal dopamine levels in human opioid addiction. Despite our experimental paradigm producing marked expectation, no increase in dopamine levels in any striatal region was detected. In addition there was no increase in regional striatal dopamine levels following a rewarding dose (50 mg) of intravenous heroin.

Salient drug cues and giving heroin in their first [11C]raclopride PET scan resulted in increased levels of expectation at the second scan in all participants. We enhanced the cues for the opioid-dependent participants compared with our previous study (Daglish et al. 2008). Because passive administration of drugs has been shown to result in smaller increases in dopamine compared with a self-administration (Leyton 2007), a webcam was used so the participants could see the highly salient ‘flashback’ and injection of heroin. Leyton emphasizes the importance of cues in his ‘two-factor dopamine model’ based on evidence from studies with psychostimulants (Leyton 2007). However, his model posits that low dopamine responsivity would be associated with the absence of cues rather than the salient cues in our study. Despite our highly salient injection procedure, we were still not able to show any changes in striatal dopamine levels in substitute-maintained opioid-dependent participants.

Previous neuroimaging studies in drug addiction have reported increased dopamine levels in abstinent individuals associated with salient videos, but have measured ‘craving or urge’, ‘intentions to use’, ‘desire’ or ‘need or want’ rather than ‘expectation’ (Volkow et al. 2006, 2010; Wong et al. 2006; Zijlstra et al. 2008). While there are similarities between expectation and craving, expectation generally implies looking forward to something positive or good, whereas craving has a sense of need and urgency that may be more present in abstinence. In contrast to expectation, craving to use did not vary during the scans, probably because participants knew they were going to receive heroin and/or their substitute medication. It is therefore possible that increased striatal dopamine levels are associated with craving rather than expectation.

Expectation of therapeutic benefit from a dopaminergic agonist in patients with Parkinson's disease has been shown to increase dopamine levels in the ventral striatum and perception of clinical benefit to increases in the dorsal striatum (de la Fuente-Fernández et al. 2002). Similarly expectation of analgesia has been shown to be associated with increased dopamine levels in the striatum (Scott et al. 2007). The anticipation of therapeutic benefit in patients with Parkinson's disease has been likened to the expectation of reward. However, patients expect to gain relief from their physical disorder, which is akin to negative rather than positive reinforcement. Consequently increased dopamine may be associated with relief from a negative state (cf. bupropion in smoking cessation), whereas in our study, the opioid-dependent participants were not in withdrawal and instead experienced a ‘high’ from their substance of abuse. Another factor may be that there was 100% certainty they would receive heroin because a study with Parkinson's patients reported that striatal dopamine levels increased maximally with 75% certainty and not at all with 100% certainty (Lidstone et al. 2010). Our results are however consistent with other studies where expectation of caffeine in habitual coffee drinkers or of intravenous glucose in healthy volunteers was not associated with increased striatal dopamine levels (Kaasinen et al. 2004; Haltia et al. 2008).

Our findings also speak to Schultz's work in primates implicating dopamine neuronal firing in learning and expectation of reward, on which we based our hypothesis (Schultz 2010). Schultz, Dayan & Montague (1997) showed that after repeated pairings of cues followed by reward, the timing of dopamine neuron activation changed from just after reward delivery to the time of cue onset, with a loss of dopaminergic response to the predicted reward itself. Because reward was defined as involving a variety of processes including hedonic feelings and generating approach behaviour, it may be that dopamine is more associated with the latter, which did not occur in our study because they were given the drug. However, Schultz also showed that if the conditioned cue was presented and no subsequent reward delivered, a reduction in dopamine neuron activity was seen. Consistent with this, our voxelwise analysis of the expectation scan showed small clusters of reduced dopamine levels after the non-rewarding dose (0.1 mg) of heroin. While we report this finding cautiously because it was found on exploratory analysis, it is to our knowledge the first evidence in humans of dopamine's involvement in reward prediction error.

We again found that a rewarding dose (50 mg) of heroin did not result in significant increases in striatal dopamine in opioid-maintained individuals (see also Daglish et al. 2008). Our exploratory voxelwise analysis revealed small clusters of reduced dopamine levels that are consistent with a study of another opioid agonist, alfentanil, in healthy volunteers (Hagelberg et al. 2002). In contrast a remifentanil infusion has been reported to increase striatal dopamine levels measured with [18F]fallypride PET in healthy volunteers and abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals, but there was no relationship to craving (Spreckelmeyer et al. 2011).

Our finding that striatal dopamine levels were not increased by a rewarding dose of heroin is consistent with studies in cocaine or alcohol addiction, showing blunted methylphenidate-induced or amphetamine-induced dopamine release (Volkow et al. 1997; Martinez et al. 2005, 2007). Methylphenidate-stimulated dopamine release has also been shown to be blunted in abstinent opioid-dependent individuals although no subjective effects were reported (Martinez et al. 2012). However, importantly, neither amphetamine nor methylphenidate are the participants' ‘drug of choice’ given by the usual route, as was the case in our study. It appears therefore that changes in dopamine can occur in the absence of pronounced subjective effects, and that the rewarding effects of opioids can occur in the absence of detectable dopamine levels.

While the impact of drug-taking status and opioid maintenance medications on the dopaminergic system remains to be fully characterized, it may have been an important factor in our experiments. Cue-induced increases in dopamine have been reported in abstinent cocaine-dependent or opioid-dependent individuals (Volkow et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2006; Zijlstra et al. 2008), whereas the opioid-dependent participants in both of our studies were maintained on methadone (except one participant on buprenorphine) and injecting heroin intermittently (note it would be unethical and dangerous to administer heroin to non-maintained individuals). Pre-clinical evidence suggests that acute administration of methadone blocks dopamine receptors and increases dopaminergic turnover, whereas in methadone addicts lower levels of cerebrospinal fluid homovanillic acid suggest reduced dopamine turnover (Tamarkin, Goodwin & Axelrod 1970; Sasame et al. 1972; Clemens & Sawyer 1974). Therefore a reduction in dopamine turnover could result in difficulty in detecting any dopamine increase with ‘expectation’ or ‘high’, which may have been the case in the present study. It may also be that part of methadone's efficacy as a maintenance treatment is due to its ability to blunt dopaminergic responses, thereby reducing craving and cue reactivity to heroin.

Both our studies, showing no changes in striatal dopamine in opioid-maintained individuals, are however consistent with evidence from animal models. Unlike for cocaine, studies have shown that opioid reinforcement is not critically dependent on an intact mesolimbic dopaminergic system (Pettit et al. 1984; Van Ree & Ramsey 1987; Gerrits & Van Ree 1996). High impulsivity in rats is associated with low D2/3 receptor levels in the ventral striatum, and increased vulnerability to lose control over cocaine intake and relapse to cocaine seeking after abstinence but not to heroin use (Dalley et al. 2007; McNamara et al. 2010). Martinez et al. (2012) also reported that unlike their studies with cocaine-dependent individuals, methylphenidate-stimulated dopamine release did not correlate with heroin self-administration. A recent comparison also strongly argued for important distinctions between psychostimulant and opioid addiction, including in the dopamine system (Badiani et al. 2011). We therefore suggest that there is good evidence for dopamine playing a different role depending on the substance of abuse.

While PET has been a highly useful tool for studying neurotransmitter systems in man, its sensitivity is limited. It is therefore possible that any dopamine release induced either by the expectation of heroin or heroin itself is too small or localized to be detected by current [11C]raclopride PET scan and analysis techniques. It is also possible that the sample size of 10 participants was too small to detect any dopamine release. The study was adequately powered (0.8) to detect a 3.6% change in overall [11C]raclopride binding consistent with other studies that reported significant changes of 4–5% in [11C]raclopride binding with cue exposure (Volkow et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2006). The power calculation used a within-volunteer SD of 3.6% for overall striatal [11C]raclopride binding, calculated from our previously reported test–retest study (Stokes et al. 2010). Significant increases in dopamine to treatment expectation (22%; de la Fuente-Fernández et al. 2002), stimulant administration (16%; Volkow et al. 2002) and alcohol administration (15%; Boileau et al. 2003) have also been reported with similar or lower participant numbers. In addition, we saw both increased and decreased BPND values in all striatal areas without a consistent trend. Using the observed differences between ‘early versus late’ phases and between scans, over a hundred participants would have had to be scanned to generate a significant finding that is clearly impracticable and unethical. The study had to overcome two major challenges: firstly that participants were required to attend for four scans (three PET and one MRI), and secondly the recruitment of opioid-dependent individuals without co-morbid stimulant or benzodiazepine abuse. Consequently, to ensure a sufficient number of such participants were recruited to robustly test our hypotheses, the study took 5 years to complete. A further limitation of all [11C]raclopride PET studies is the uncertainty about what any differences in BPND represent. While changes are measurable following both pharmacological and psychological interventions, these may reflect either changes in synaptic dopamine concentration or in dopamine D2/3 receptor availability (Laruelle 2000; Egerton et al. 2009).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that striatal dopamine release does not appear to play a key role in mediating either the expectation or ‘high’ associated with heroin use in opioid-dependent individuals maintained on substitute medication. Given how many opioid-dependent individuals are in maintenance programmes, it is vital that we understand the impact of substitute medications on the dopaminergic system. In addition, there is growing evidence that dopamine is likely to play differing roles in opioid addiction compared with alcohol and cocaine addiction (Badiani et al. 2011). Our results provide further evidence for the debate about the role of dopamine in opioid addiction because studies in abstinence and those on substitute medication suggest its role may differ, and the impact on clinical outcomes deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant (G0400575) from the Medical Research Council and was completed in collaboration with Imanet, GE Healthcare. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Authors Contribution

DJN, ARL-H, DJB, AGR and SJW were responsible for the study concept and design. BJW, AGR, SJW and LGT contributed to the acquisition of PET scans and clinical data. BJW, LGT, JFM, PRS, FET, ARL-H and DJN contributed to data analysis and interpretation of findings. BJW, ARL-H, DJN and LGT drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed content and approved the final version for publication.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. 4th edn. [Google Scholar]

- Badiani A, Belin D, Epstein D, Calu D, Shaham Y. Opiate versus psychostimulant addiction: the differences do matter. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:685–700. doi: 10.1038/nrn3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Assaad JM, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C, Leyton M, Diksic M, Tremblay RE, Dagher A. Alcohol promotes dopamine release in the human nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 2003;49:226–231. doi: 10.1002/syn.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RE, Breier A, de Bartolomeis A, Saunders RC, Su TP, Schmall B, Der MG, Pickar D, Eckelman WC. Quantification of amphetamine-induced changes in [11C]raclopride binding with continuous infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:437–447. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens JA, Sawyer BD. Evidence that methadone stimulates prolactin release by dopamine receptor blockade. Endocr Res Commun. 1974;1:373–378. doi: 10.3109/07435807409053832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daglish MR, Williams TM, Wilson SJ, Taylor LG, Eap CB, Augsburger M, Giroud C, Brooks DJ, Myles JS, Grasby P, Lingford-Hughes AR, Nutt DJ. Brain dopamine response in human opioid addiction. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:65–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Fryer TD, Brichard L, Robinson ES, Theobald DE, Lääne K, Peña Y, Murphy ER, Shah Y, Probst K, Abakumova I, Aigbirhio FI, Richards HK, Hong Y, Baron JC, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton A, Mehta MA, Montgomery AJ, Lappin JM, Howes OD, Reeves SJ, Cunningham VJ, Grasby PM. The dopaminergic basis of human behaviors: a review of molecular imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:1109–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Fernández R, Phillips AG, Zamburlini M, Sossi V, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Dopamine release in human ventral striatum and expectation of reward. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136:359–363. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrits MA, Van Ree JM. Effect of nucleus accumbens dopamine depletion on motivational aspects involved in initiation of cocaine and heroin self-administration in rats. Brain Res. 1996;713:114–124. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RN, Lammertsma AA, Hume SP, Cunningham VJ. Parametric imaging of ligand-receptor binding in PET using a simplified reference region model. Neuroimage. 1997;6:279–287. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelberg N, Kajander JK, Någren K, Hinkka S, Hietala J, Scheinin H. Mu-receptor agonism with alfentanil increases striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding in man. Synapse. 2002;45:25–30. doi: 10.1002/syn.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia LT, Rinne JO, Helin S, Parkkola R, Någren K, Kaasinen V. Effects of intravenous placebo with glucose expectation on human basal ganglia dopaminergic function. Synapse. 2008;62:682–688. doi: 10.1002/syn.20541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasinen V, Aalto S, Någren K, Rinne JO. Expectation of caffeine induces dopaminergic responses in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2352–2356. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4(3 Pt 1):153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: a critical review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:423–451. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law F, Bailey J, Allen D, Melichar J, Myles J, Mitcheson M, Lewis J, Nutt D. The feasibility of abrupt methadone–buprenorphine transfer in British opiate addicts in an outpatient setting. Addict Biol. 1997;2:191–200. doi: 10.1080/13556219772732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton M. Conditioned and sensitized responses to stimulant drugs in humans. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1601–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidstone SC, Schulzer M, Dinelle K, Mak E, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, de la Fuente-Fernández R, Phillips AG, Stoessl AJ. Effects of expectation on placebo-induced dopamine release in Parkinson disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:857–865. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Gil R, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Perez A, Kegeles L, Talbot P, Evans S, Krystal J, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Narendran R, Foltin RW, Slifstein M, Hwang DR, Broft A, Huang Y, Cooper TB, Fischman MW, Kleber HD, Laruelle M. Amphetamine-induced dopamine release: markedly blunted in cocaine dependence and predictive of the choice to self-administer cocaine. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:622–629. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Saccone PA, Liu F, Slifstein M, Orlowska D, Grassetti A, Cook S, Broft A, Van Heertum R, Comer SD. Deficits in dopamine d(2) receptors and presynaptic dopamine in heroin dependence: commonalities and differences with other types of addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, Mawlawi O, Hwang DR, Huang Y, Cooper T, Kegeles L, Zarahn E, Abi-Dargham A, Haber SN, Laruelle M. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography. Part II: amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the functional subdivisions of the striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:285–300. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000048520.34839.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara R, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ, Belin D. Trait-like impulsivity does not predict escalation of heroin self-administration in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:453–464. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1974-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AJ, Lingford-Hughes AR, Egerton A, Nutt DJ, Grasby PM. The effect of nicotine on striatal dopamine release in man: a [11C]raclopride PET study. Synapse. 2007;61:637–645. doi: 10.1002/syn.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AJ, Thielemans K, Mehta MA, Turkheimer F, Mustafovic S, Grasby PM. Correction of head movement on PET studies: comparison of methods. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1936–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson S, Cordero R, Burlinson S. Screening and semi-quantitative analysis of post mortem blood for basic drugs using gas chromatography/ion trap mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;813:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:167–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00427441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasame HA, Perez-Cruet J, Di Chiara G, Tagliamonte A, Tagliamonte P, Gessa GL. Evidence that methadone blocks dopamine receptors in the brain. J Neurochem. 1972;19:1953–1957. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Dopamine signals for reward value and risk: basic and recent data. Behav Brain Funct. 2010;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Individual differences in reward responding explain placebo-induced expectations and effects. Neuron. 2007;55:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, Vagg P, Jacobs G. Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spreckelmeyer KN, Paulzen M, Raptis M, Baltus T, Schaffrath S, Van Waesberghe J, Zalewski MM, Rösch F, Vernaleken I, Schäfer WM, Gründer G. Opiate-induced dopamine release is modulated by severity of alcohol dependence: an [(18)F]fallypride positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes PR, Egerton A, Watson B, Reid A, Breen G, Lingford-Hughes A, Nutt DJ, Mehta MA. Significant decreases in frontal and temporal [11C]-raclopride binding after THC challenge. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1521–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes PR, Mehta MA, Curran HV, Breen G, Grasby PM. Can recreational doses of THC produce significant dopamine release in the human striatum? Neuroimage. 2009;48:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamarkin NR, Goodwin FK, Axelrod J. Rapid elevation of biogenic amine metabolites in human CSF following probenecid. Life Sci I. 1970;9:1397–1408. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(70)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ree JM, Ramsey N. The dopamine hypothesis of opiate reward challenged. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;134:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Franceschi D, Maynard L, Ding YS, Gatley SJ, Gifford A, Zhu W, Swanson JM. Relationship between blockade of dopamine transporters by oral methylphenidate and the increases in extracellular dopamine: therapeutic implications. Synapse. 2002;43:181–187. doi: 10.1002/syn.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, Chen AD, Dewey SL, Pappas N. Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature. 1997;386:830–833. doi: 10.1038/386830a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F. Addiction: beyond dopamine reward circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15037–15042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010654108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F, Baler R. Addiction: decreased reward sensitivity and increased expectation sensitivity conspire to overwhelm the brain's control circuit. Bioessays. 2010;32:748–755. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ma Y, Fowler JS, Zhu W, Maynard L, Telang F, Vaska P, Ding YS, Wong C, Swanson JM. Expectation enhances the regional brain metabolic and the reinforcing effects of stimulants in cocaine abusers. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11461–11468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11461.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe H, Endres CJ, Breier A, Schmall B, Eckelman WC, Carson RE. Measurement of dopamine release with continuous infusion of [11C]raclopride: optimization and signal-to-noise considerations. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Glue P, Ball D, Nutt DJ. Saccadic eye movement parameters in normal subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;86:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(93)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DF, Kuwabara H, Schretlen DJ, Bonson KR, Zhou Y, Nandi A, Brasić JR, Kimes AS, Maris MA, Kumar A, Contoreggi C, Links J, Ernst M, Rousset O, Zukin S, Grace AA, Lee JS, Rohde C, Jasinski DR, Gjedde A, London ED. Increased occupancy of dopamine receptors in human striatum during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2716–2727. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zijlstra F, Booij J, van den Brink W, Franken IH. Striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding and dopamine release during cue-elicited craving in recently abstinent opiate-dependent males. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]