Abstract

Background

Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) was first described in 2003 as a method for lengthening and tapering of the bowel in short bowel syndrome. The aim of this multicentre study was to review the outcome of a Swedish cohort of children who underwent STEP.

Methods

All children who had a STEP procedure at one of the four centres of paediatric surgery in Sweden between September 2005 and January 2013 were included in this observational cohort study. Demographic details, and data from the time of STEP and at follow-up were collected from the case records and analysed.

Results

Twelve patients had a total of 16 STEP procedures; four children underwent a second STEP. The first STEP was performed at a median age of 5·8 (range 0·9–19·0) months. There was no death at a median follow-up of 37·2 (range 3·0–87·5) months and no child had small bowel transplantation. Seven of the 12 children were weaned from parenteral nutrition at a median of 19·5 (range 2·3–42·9) months after STEP.

Conclusion

STEP is a useful procedure for selected patients with short bowel syndrome and seems to facilitate weaning from parenteral nutrition. At mid-term follow-up a majority of the children had achieved enteral autonomy. The study is limited by the small sample size and lack of a control group. Good results in selected children

Introduction

Intestinal failure has been defined as the inability of the gastrointestinal tract to sustain adequate growth, hydration and electrolyte homeostasis in children without parenteral nutrition. Short bowel syndrome is the most common cause of paediatric intestinal failure1. The management of these complex patients remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Many centres have developed multidisciplinary teams that use nutritional, pharmacological and surgical approaches to facilitate bowel rehabilitation. This approach has been shown to improve outcomes2.

The surgical management of short bowel syndrome comprises strategies to preserve bowel length in the neonate with necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroschisis, small bowel atresia or volvulus. Resections should be as limited as possible. Second-look operations are useful to reassess bowel viability 24–48 h after the first procedure.

It has been shown that establishment of bowel continuity results in faster weaning from parenteral nutrition3. Autologous intestinal reconstruction was first introduced by Bianchi4, who described longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tapering in 1980. More recently, in 2003, serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) was described as a procedure for lengthening and tapering of the dilated short bowel5,6. The overall outcome of the two procedures appears to be similar7. Experimental studies have shown that the intestinal absorption of nutrients improves after STEP. In a pig model8,9 it was shown that both baseline and hormone-stimulated motility was preserved after STEP.

The aim of this study was to review the outcome of a Swedish cohort of children who underwent STEP.

Methods

The audit was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board. All children who underwent STEP at one of the four Swedish centres of paediatric surgery between September 2005 and January 2013 were included in this observational cohort study. The participating centres were: Queen Silvia's Children's Hospital in Gothenburg, Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm and Akademiska Hospital in Uppsala.

Data were collected retrospectively from the case records. The following parameters were recorded: birth weight, gestational age, sex, aetiology of short bowel syndrome and number of surgical procedures before STEP. Data on the indication for STEP and re-STEP, total small bowel length before and after the reconstruction, maximal bowel width at STEP and re-STEP, and number of stapler firings were collected. The ratio of enteral/total caloric intake before STEP and at follow-up was calculated. The date when full enteral autonomy was achieved, if applicable, was recorded. Serum bilirubin and liver enzyme values before STEP and at follow-up were compared. Z-scores for weight for age and height for age were calculated using World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Episodes of septicaemia with positive blood cultures were registered before and after STEP.

Surgical procedure

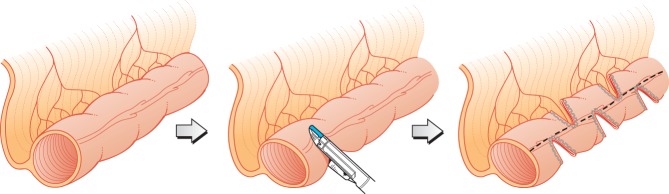

The abdomen was usually approached through a transverse incision. The total small bowel length was measured antimesenterically, using a suture, before the reconstruction. Bowel that was dilated more than 4 cm, which has been considered the lower limit for the procedure10, was subjected to reconstruction. The mesentery was opened, and a stapler was introduced through the opening and fired perpendicular to the direction of the bowel. The procedure was continued from alternating sides, creating a zig-zag pattern and aiming at a bowel diameter of approximately 2 cm (Fig. 1). In some patients in the later part of the series, a corner stitch was used to avoid leakage or bleeding from the staple line. The total small bowel length was measured antimesenterically after the reconstruction. After operation enteral feeding was started as soon as there were no gastric aspirates.

Fig 1.

In serial transverse enteroplasty, staplers are fired from alternating sides perpendicular to the direction of the bowel

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented median (range). The χ2 test was used for analysis of categorical variables. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare bowel length, levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes, and Z-scores at the time of STEP and at follow-up. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS® version 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Twelve children, six boys and six girls, who underwent a total of 16 STEP procedures were included in the study. The median gestational age was 34 (31–37) weeks. The median birth weight was 2550 (1200–3475) g. The aetiology of short bowel syndrome was small bowel atresia (11), gastroschisis (5) and volvulus (3). The disorders occurred as a single condition or in combination. Four patients had a normal colon and ileocaecal valve, whereas in eight the ileocaecal valve and proximal part of the colon were missing or had been resected. The children had undergone 3 (1–7) abdominal operations before STEP. The indication for STEP was dysmotility with intolerance to enteral feeding in all infants. All patients also had a small bowel diameter that exceeded 4 cm on abdominal radiography. Nine patients had had recurrent episodes of septicaemia with positive blood cultures. These were both catheter-associated infections and suspected translocation secondary to bacterial overgrowth. Four patients had intestinal failure-associated liver disease before STEP. The ratio of enteral to total caloric intake was 0·14 (0·03–0·43) before STEP.

Serial transverse enteroplasty

The STEP procedure was performed at 5·8 (0·9–19·0) months of age. The total small bowel length was 45 (21–55) cm before STEP and 65 (29–90) cm after operation (P = 0·005). Total small bowel length after STEP was not available for two patients. The bowel was 48 (27–112) per cent longer after STEP. Maximum small bowel diameter before STEP was 5 (4–8·5) cm. A median of 9 (4–20) staple firings were used for the reconstruction.

One child had a postoperative bleed that required reoperation owing to a haematoma close to one of the staple lines. There were no staple-line leaks. Four patients showed initial improvement but the reconstructed small bowel redilated and a second STEP was subsequently required. The indication for re-STEP was deteriorating tolerance to enteral feeding and an increasing need for parenteral nutrition in all instances. One patient also had a suspected anastomotic stricture, which was not evident during the redo procedure, and one patient had recurrent episodes of septicaemia.

The second STEP was performed 12·1 (1·1–15·4) months after the initial STEP. At re-STEP the bowel was 87·5 (50–100) cm before and 121 (53–125) cm after the reconstruction (P = 0·109). The maximum bowel diameter was 5·5 (4–6) cm. A median of 10 (2–22) staplers were fired. There were no early surgical complications after the second STEP.

One patient presented with iron deficiency anaemia and microscopic bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract approximately 3 years after the second STEP. Endoscopy did not show the source in the upper gastrointestinal tract or the colon. The child was scheduled for a capsule endoscopy.

Outcomes

The outcome at last follow-up is summarized in Table 1. The weight for age and height for age Z-scores before the first STEP were compared with data at last follow-up. The Z-score for weight for age was −1·66 (−5·92 to −0·65) at the time of STEP and −0·63 (−2·13 to −0·04) at follow-up (P = 0·100). Respective Z-score values for height for age were −0·86 (−6·21 to 0·13) and −0·20 (−3·05 to 1·15) (P = 0·016). Data on height for age were missing for one patient. Only height for age Z-scores improved significantly.

Table 1.

Outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty

| No. of patients* | |

|---|---|

| Follow-up after STEP (months) (n =12)† | 37·2 (3·0–87·5) |

| Follow-up after re-STEP (months) (n = 4)† | 19·7 (17·5–51·6) |

| Enteral autonomy | 7 of 12 |

| After STEP | 5 of 8 |

| After re-STEP | 2 of 4‡ |

| Time to enteral autonomy (months) (n = 7)† | 19·5 (2·3–42·9) |

| Ratio of enteral/total caloric intake (n = 5) | 0·22–0·62 |

| Septicaemia with positive blood culture after STEP/re-STEP | 10 of 12 |

| Small bowel transplantation | 0 of 12 |

| Death | 0 of 12 |

Unless indicated otherwise

values are median (range). STEP, serial transverse enteroplasty.

P = 0.679 versus after STEP (χ2 test).

Levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes before STEP and at follow-up are shown in Table 2. There was a statistically significant improvement in both bilirubin and liver enzyme levels, probably as a consequence of increased enteral tolerance, resulting in less need for parenteral nutrition. The intestinal failure-associated liver disease improved in all four children who had cholestasis and raised levels of liver enzymes before STEP.

Table 2.

Bilirubin and liver enzymes before serial transverse enteroplasty and at follow-up

| Before STEP | At follow-up | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin (mmol/l) | 10·5 (2·7–242·0) | 3·5 (2·0–15·0) | 0·014 |

| AST (mmol/l) | 1·07 (0·37–6·60) | 0·64 (0·33–1·30) | 0·008 |

| ALT (mmol/l) | 1·0 (0·19–3·40) | 0·51 (0·17–1·70) | 0·050 |

Values are median (range). STEP, serial transverse enteroplasty; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Discussion

Most of the previous outcome data after STEP come from large centres in North America. Apart from the experience published from Helsinki11, this is the largest series of children managed with STEP in a European context. Seven of the 12 patients were weaned off parenteral nutrition by a median of 19·5 months after the operation. Some of the children who remain dependent on parenteral nutrition were operated on recently and are still improving, probably as a result of an ongoing adaptation process. It has been shown that adaptation continues for several years1. Three years after STEP there was no mortality and no child had undergone small bowel transplantation.

The small sample size limits generalization of the results. Large numbers (111) have currently been reported only from the STEP Data Registry12, administered from Boston, Massachusetts, USA, which illustrates the need for multicentre trials in rare conditions such as paediatric intestinal failure. Single-centre experience from well established intestinal rehabilitation centres comprises only up to 16 children13,14.

The most important limitation of this study is the lack of control data. Pakarinen and colleagues11 showed that children with short bowel syndrome had a similar mortality rate and parenteral nutrition dependency at 4 years with or without an autologous intestinal reconstruction. Squires and co-workers15 reviewed the outcome of 272 children with short bowel syndrome managed in 14 North American centres. Approximately 10 per cent of the whole group had undergone autologous intestinal reconstruction. At 3 years approximately 44, 26 and 23 per cent had achieved enteral autonomy, died or required small bowel transplantation respectively. This illustrates that many children are weaned off parenteral nutrition as a result of the adaptation process alone, without autologous intestinal reconstruction15. Similar data were reported in a study16 of 28 children with ultrashort small bowel syndrome (less than 20 cm small bowel). Approximately half of these had undergone autologous bowel reconstruction. Some 48 per cent of the patients were weaned from parenteral nutrition.

The outcomes reported after STEP in some of the larger published series are summarized in Table 3. Between 38 and 88 per cent of the children were weaned from parenteral nutrition. In most of these studies11–14,17,18 a few children needed small bowel transplantation and there were some deaths. It is obvious that the population of children with intestinal failure is quite heterogeneous, which may contribute to the variation in outcome between centres. Children with intestinal failure owing to a short, dilated small bowel usually undergo autologous intestinal reconstruction if they cannot be weaned from parenteral nutrition, particularly if they also have complications such as intestinal failure-associated liver disease or recurrent episodes of septicaemia. On the other hand, as pointed out by Javid et al.13, there are limited data showing which patients actually benefit from a lengthening and tapering procedure. The authors believe it is difficult from an ethical point of view to perform a randomized clinical trial to delineate this, although it would be useful.

Table 3.

Summary of published outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty

| Reference | Year | Study location | n | Follow-up | Enteral autonomy (%) | Small bowel transplantation | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones et al.12 | 2013 | International STEP Data Registry | 97* | Median 21 months | 47 | 5 | 11 |

| Wales et al.17 | 2007 | Toronto | 14 | Mean 23 months | 88 | 2 | 3 |

| Ching et al.14 | 2009 | Boston | 16 | Median 23 months | 38 | 2 | 0 |

| Oliveira et al.18 | 2012 | Toronto | 12 | > 5 years | 88 | 2 | 2 |

| Pakarinen et al.11 | 2013 | Helsinki | 7 | Median 6·9 years | 86 | 0 | 1 |

| Javid et al.13 | 2013 | Seattle | 16 | Median 26 months | 60 | 2 | 2 |

| Present study | 2014 | Sweden | 12 | Median 37·2 months | 58 | 0 | 0 |

A total of 111 patients were included in the registry, but there were adequate data for analysis on only 97. STEP, serial transverse enteroplasty.

Redilatation has been considered an indicator for poor outcome after autologous intestinal reconstruction19. However, it is technically feasible to do a second STEP20. In the present series there was no difference in the proportion of children who achieved enteral autonomy after the first and second STEP procedure. Half of the children could be weaned from parenteral nutrition after a second STEP, similar to data reported previously21.

Javid and colleagues13 showed that weight for age improved after STEP, but not height for age. In the present series height for age improved, but not weight for age. It may be speculated that the anthropometric differences before and after STEP are small because most patients have a reasonable nutritional status before STEP, even though they depend on parenteral nutrition. Height is often the last parameter to catch up when intestinal failure is compensated for.

Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding due to staple-line ulcers is a long-term complication14,17. Gibbons and co-workers22 presented a case in which staple-line ulcers were revealed with video capsule endoscopy. It was shown recently in an experimental model that STEP could be accomplished safely with application of radiofrequency energy (LigaSure™; Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) instead of using a conventional stapler23. This may potentially prevent bleeding complications from staple-line ulcers.

This Swedish nationwide audit of STEP in children has shown satisfactory results comparable with published international results. At mid-term follow-up a majority of the patients had achieved enteral autonomy. The authors believe that these children should be cared for at intestinal rehabilitation centres with experienced multidisciplinary teams of paediatric gastroenterologists, nutritionists and paediatric surgeons.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gutierrez IM, Kang KH, Jaksic T. Neonatal short bowel syndrome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;16:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modi BP, Langer M, Ching YA, Valim C, Waterford SD, Iglesias J, et al. Improved survival in a multidisciplinary short bowel program. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andorsky DJ, Lund DP, Lillehei CW, Jaksic T, Dicanzio J, Richardson DS, et al. Nutritional and other postoperative management of neonates with short bowel syndrome correlates with clinical outcomes. J Pediatr. 2001;139:27–33. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.114481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchi A. Intestinal loop lengthening – a technique for increasing small bowel length. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(80)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HB, Fauza D, Garza J, Oh JT, Nurko S, Jaksic T. Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP): a novel bowel lengthening procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:425–429. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HB, Lee PW, Garza J, Duggan C, Fauza D, Jaksic T. Serial transverse enteroplasty for short bowel syndrome: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:881–885. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King B, Carlson G, Khalil BA, Morabito A. Intestinal bowel lengthening in children with short bowel syndrome: a systematic review of the Bianchi and STEP procedures. World J Surg. 2013;37:694–704. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1879-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang RW, Javid PJ, Oh JT, Andreoli S, Kim HB, Fauza D, et al. Serial transverse enteroplasty enhances intestinal function in a model of short bowel syndrome. Ann Surg. 2006;243:223–228. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197704.76166.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modi BP, Ching YA, Langer M, Donovan K, Fauza DO, Kim HB, et al. Preservation of intestinal motility after the serial transverse enteroplasty procedure in a large animal model of short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung MW, Chan IH, Chao NS, Wong BP, Liu KK. Serial transverse enteroplasty for short bowel syndrome: Hong Kong experience. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18:35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakarinen MP, Kurvinen A, Koivusalo AI, Iber T, Rintala RJ. Long-term controlled outcome after autologous intestinal reconstruction surgery in treatment of severe short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones BA, Hull MA, Potanos KM, Zurakowski D, Fitzgibbons SC, Ching YA, et al. International STEP Data Registry Report of 111 consecutive patients enrolled in the International Serial Transverse Enteroplasty (STEP) Data Registry: a retrospective observational study. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javid PJ, Sanchez SE, Horslen SP, Healey PJ. Intestinal lengthening and nutritional outcomes in children with short bowel syndrome. Am J Surg. 2013;205:576–580. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ching YA, Fitzgibbons S, Valim C, Zhou J, Duggan C, Jaksic T, et al. Long-term nutritional and clinical outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty at a single institution. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:939–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Squires RH, Duggan C, Teitelbaum DH, Wales PW, Balint J, Venick R, et al. Pediatric Intestinal Failure Consortium Natural history of pediatric intestinal failure: initial report from the Pediatric Intestinal Failure Consortium. J Pediatr. 2012;161:723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Infantino BJ, Mercer DF, Hobson BD, Fischer RT, Gerhardt BK, Grant WJ, et al. Successful rehabilitation in pediatric ultrashort small bowel syndrome. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1361–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wales PW, de Silva N, Langer JC, Fecteau A. Intermediate outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1804–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira C, de Silva N, Wales PW. Five-year outcomes after serial transverse enteroplasty in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyasaka EA, Brown PI, Teitelbaum DH. Redilatation of bowel after intestinal lengthening procedures – an indicator for poor outcome. J Pediatr Surgery. 2011;46:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlich PE, Mychaliska GB, Teitelbaum DH. The 2 STEP: an approach to repeating a serial transverse enteroplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:819–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andres AM, Thompson J, Grant W, Botha J, Sunderman B, Antonson D, et al. Repeat surgical bowel lengthening with the STEP procedure. Transplantation. 2008;85:1294–1299. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817268ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbons TE, Casteel HB, Vaughan JF, Dassinger MS. Staple line ulcers: a cause of chronic GI bleeding following STEP procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:E1–E3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suri M, Dicken B, Nation PN, Wizzard P, Turner JM, Wales PW. The next step? Use of tissue fusion technology to perform the serial transverse enteroplasty – proof of principle. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:938–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]