Abstract

The Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR) collects data on clinical islet isolations and transplants. This retrospective report analyzed 1017 islet isolation procedures performed for 537 recipients of allogeneic clinical islet transplantation in 1999–2010. This study describes changes in donor and islet isolation variables by era and factors associated with quantity and quality of final islet products. Donor body weight and BMI increased significantly over the period (p < 0.001). Islet yield measures have improved with time including islet equivalent (IEQ)/particle ratio and IEQs infused. The average dose of islets infused significantly increased in the era of 2007–2010 when compared to 1999–2002 (445.4 ± 156.8 vs. 421.3 ± 155.4 ×103 IEQ; p < 0.05). Islet purity and total number of β cells significantly improved over the study period (p < 0.01 and <0.05, respectively). Otherwise, the quality of clinical islets has remained consistently very high through this period, and differs substantially from nonclinical islets. In multivariate analysis of all recipient, donor and islet factors, and medical management factors, the only islet product characteristic that correlated with clinical outcomes was total IEQs infused. This analysis shows improvements in both quantity and some quality criteria of clinical islets produced over 1999–2010, and these parallel improvements in clinical outcomes over the same period.

Keywords: Clinical research/practice, diabetes: type 1, endocrinology/diabetology, health services and outcomes research, islet isolation, islet transplantation, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), pancreas/simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation, registry/registry analysis

Introduction

Over the last two decades, numerous studies have attempted to document the donor and procedural factors that significantly influence the success of pancreatic islet isolation and clinical transplantation 1–12. The following donor variables are commonly identified in those studies: donor age, BMI, metabolic condition, pancreas characteristics, cause of death and cold ischemia time (CIT). Various evaluations of the procedures have been performed including processing times, pancreas preservation method, digestion enzyme selection and purification method. The most frequently used primary outcome in these studies pertained to islet yield as represented by total islet equivalent (IEQ) and IEQ/g pancreas or IEQ/kg of recipient body weight. These reports have laid a nearly unanimous emphasis on the importance of reaching a critical minimum islet mass to achieve transplant success.

Consistent results across the studies have been observed for some variables, such as age and BMI; however, controversial findings also have been reported 12,13. The lack of a consistent or sufficiently detailed reporting of variables and outcome measures limits the efficacy of meta-analysis to resolve these debates. In addition, recent investigations have begun to highlight the importance of nonyield-based indicators in predicting the ultimate goal of any islet transplantation procedure, normalization of blood sugar control and a relief from diabetic symptoms in the transplant recipients 4,10,11.

The current investigation represents a comprehensive review of islet characteristics, analyzing data from 1017 clinical islet isolations conducted in North American and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) European and Australian centers through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) - and JDRF-sponsored Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR) database. The CITR has collected data on donors; pancreas procurement, isolation and product characteristics; and baseline and follow-up on recipients of human allogeneic islet transplants from 1999 to the present. CITR operates with all sites and the Coordinating Center undergoing annual review of the research protocol by local Internal Review Boards. This collaboration, concomitant with the standardization of variable and outcome reporting, has produced the largest and most thorough collection on the production of human clinical-grade islets. We focus in this report on identifying the factors that significantly impacted the yield, purity and endocrine function of the final islet product and clinical outcomes, while recipient and management characteristics are reserved for a separate analysis.

Methods

This analysis comprises data from 1017 islet transplant alone (ITA), islet after kidney (IAK) and simultaneous islet and kidney (SIK) allogeneic transplants reported to CITR from 1999 to 2010. The analysis period was divided into 4-year eras: 1999–2002, 2003–2006, 2007–2010 as reported previously for clinical outcomes 14. For multiple-donor infusions given on the same day, the donor, pancreas and procurement characteristics were averaged or summed as appropriate to characterize the composite infused preparation.

Table 1 organizes variables according to donor characteristics, procurement and processing characteristics, islet product characteristics and infusion characteristics. Data shown in Table 4 on islet product characteristics comprises the primary outcomes of this analysis, while the others are investigated as possible factors associated with these outcomes. The variables themselves may vary according to calendar year of transplant (era), continent (North America vs. the JDRF sites in Europe and Australia), ITA versus IAK/SIK and many other factors that may or may not be captured in the data. Categorical variables and outcomes are described by their distribution: in particular many are characterized as either present (1) or absent (0); those comprising several distinct levels, including preservation solution, enzyme and gradient type, are reported and analyzed as class variables. Continuous variables are described by their mean and standard deviation. Not all variables were available for all preparations. Table 1 shows the distribution of available data for each variable, excluding the missing data (i.e. treated as missing at random); hence, the percentage distributions are estimates of the actual distribution.

Table 1A.

Donor characteristics

| Total (n = 1017) | Era | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 (n = 257) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | |||

| Age (years) | 43.2 ± 12.2 (n = 846) | 42.5 ± 12.2 | 43.3 ± 11.7 | 43.6 ± 13 | |

| Gender, % (n) | |||||

| Female donor only | 37.3 (n = 379) | 38.9 (n = 100) | 36.9 (n = 174) | 36.5 (n = 105) | |

| Mixed-gender multiple-donor infusion | 3.7 (n = 38) | 5.4 (n = 14) | 4.7 (n = 22) | 0.7 (n = 2) | |

| Male donor only | 59 (n = 600) | 55.6 (n = 143) | 58.5 (n = 276) | 62.8 (n = 181) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 87.6 ± 20.5 (n = 946) | 84.1 ± 20.6 | 86.6 ± 19.8 | 93.5 ± 20.7 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 173.4 ± 9.8 (n = 994) | 172.5 ± 9 | 173.5 ± 9.9 | 174 ± 10.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 ± 6.3 (n = 944) | 28.3 ± 6.5 | 28.7 ± 6.2 | 30.9 ± 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 90.9 (n = 538) | 92.9 (n = 156) | 89 (n = 251) | 92.3 (n = 131) | |

| Mixed-ethnicity multiple-donor infusion | 1.9 (n = 11) | 2.4 (n = 4) | 2.5 (n = 7) | ||

| Hispanic | 7.3 (n = 43) | 4.8 (n = 8) | 8.5 (n = 24) | 7.7 (n = 11) | |

| Donor race, % (n) | |||||

| White | 89.8 (n = 564) | 93.9 (n = 168) | 87.5 (n = 273) | 89.8 (n = 123) | |

| Cause of death, % (n) | |||||

| Trauma | 33.2 (n = 308) | 32.9 (n = 76) | 32 (n = 145) | 35.8 (n = 87) | |

| Cerebrovascular/stroke | 58.4 (n = 541) | 55.8 (n = 129) | 61.1 (n = 277) | 55.6 (n = 135) | |

| History, % (n) | |||||

| Hypertension | 35.2 (n = 294) | 36.7 (n = 65) | 35.1 (n = 150) | 34.2 (n = 79) | |

| Alcohol use | 18.6 (n = 145) | 13.9 (n = 25) | 22.2 (n = 91) | 15.2 (n = 29) | |

| Laboratory results | |||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.6 (n = 809) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1 ± 0.5 | |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.7 (n = 633) | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | |

| AST (U/L) | 76.7 ± 202 (n = 655) | 115.7 ± 342.1 | 63.1 ± 128.9 | 70.9 ± 154.5 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 63.4 ± 165.1 (n = 720) | 89.3 ± 286 | 52.3 ± 107.6 | 63.6 ± 127.2 | |

| Lipase (U/L) | 1.1 ± 1.9 (n = 631) | 1 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 1.9 | 1 ± 2.2 | |

| Amylase (U/L) | 2.6 ± 5.1 (n = 726) | 2.3 ± 3.7 | 2.5 ± 4.2 | 3.4 ± 8 | |

| Preinsulin glucose (mg/dL) | 125.5 ± 38.2 (n = 743) | 129.5 ± 36 | 123.3 ± 38.5 | 126.1 ± 39.8 | |

| Maximum blood glucose (mg/dL) | 230.6 ± 83.5 (n = 773) | 247 ± 98 | 228.7 ± 84.2 | 221.7 ± 67.5 | |

| Max-Min glucose (mg/dL) | 110.7 ± 86 (n = 670) | 119.4 ± 98.6 | 109.5 ± 84.3 | 104.4 ± 75.1 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5 ± 0.5 (n = 161) | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | |

| Treatment at last admission, % (n) | |||||

| Vasopressors | 96.7 (n = 816) | 96.7 (n = 204) | 97.7 (n = 432) | 94.2 (n = 180) | |

| Steroids | 59 (n = 309) | 65.5 (n = 78) | 52 (n = 157) | 71.8 (n = 74) | <0.05 |

| Insulin | 42.6 (n = 321) | 27.8 (n = 49) | 43 (n = 166) | 55.2 (n = 106) | <0.05 |

| Transfusion prerecovery | 32.9 (n = 244) | 34.8 (n = 65) | 33.7 (n = 134) | 28.8 (n = 45) | |

| Transfusion intra-operatively | 6.5 (n = 41) | 9.1 (n = 15) | 5.7 (n = 20) | 5.1 (n = 6) | |

Table 1D.

Islet product characteristics

| Total (n = 1017) | Era | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 (n = 257) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | |||

| Islet mass | |||||

| Total IEQs (×103) at time of particle count | 416 ± 156.9 (n = 773) | 417.5 ± 160.6 | 413.7 ± 159.9 | 419.2 ± 146.7 | |

| IEQ/islet particle ratio | 1.1 ± 0.6 (n = 655) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| IEQs infused (×103) | 426.5 ± 157.1 (n = 1015) | 421.3 ± 155.4 | 417.8 ± 157.6 | 445.4 ± 156.8 | <0.05 |

| Packed cell volume infused (mL) | 3.9 ± 2.2 (n = 825) | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 2 | 3.8 ± 2.8 | |

| Islet quality | |||||

| Purity (%) | 61.8 ± 18.3 (n = 770) | 59 ± 19.1 | 61.7 ± 18.5 | 65.1 ± 16.4 | <0.01 |

| Embedded islets (%) | 15.7 ± 18.7 (n = 527) | 13.6 ± 17.7 | 16.1 ± 19.5 | 16.9 ± 18 | |

| Stimulation index | 3.3 ± 3.3 (n = 693) | 3.8 ± 3.9 | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Islet viability (%) | 91.2 ± 6.2 (n = 752) | 91.4 ± 6.9 | 91.5 ± 6 | 90.2 ± 5.9 | <0.01 |

| Total beta cells (×106) | 231.1 ± 191.5 (n = 228) | 196.2 ± 180 | 235.6 ± 191.9 | 318.9 ± 201.4 | <0.05 |

| Total beta cells (×106)/kg recipient | 3.6 ± 3.1 (n = 219) | 3 ± 2.8 | 3.8 ± 3.2 | 4.5 ± 2.8 | |

| Total insulin content of islets (mg) | 3.5 ± 2.2 (n = 247) | 3.2 ± 2 | 3.6 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | |

| Total endotoxin infused (EU) | 22.7 ± 54.9 (n = 667) | 29.4 ± 60.7 | 26.1 ± 60 | 7.8 ± 26.7 | |

| Total endotoxin (EU)/kg recipient | 0.4 ± 0.8 (n = 651) | 0.5 ± 1 | 0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | |

IEQ, islet equivalent.

Associations between the variables and the outcomes were estimated by general linear models, first univariately, to identify all associations at p < 0.05, then by step-down multivariate modeling to isolate net effects after adjustment for confounders, with each islet infusion as an independent observation. For about 10% of all “infusions” islet products were derived from two to three donors administered on the same day; these are analyzed as composite infusions because clinical outcomes cannot be ascribed to one or the other donor products, but to the infusion of multiple products given on the same day. All variables in CITR including recipient and donor characteristics, islet procurement, processing and final product criteria, as well as medical management variables, were evaluated by comprehensive multivariate models for their association with clinical outcomes of islet transplantation including achievement and retention of insulin independence (≥14 days, but usually ranging many months or years), and retention of fasting C-peptide >0.3 ng/mL. These results are reported in the CITR 7th Annual Report 15, also based on the same data set as the present report. SAS V9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all computations. Definitions of the terminology shown in the tables and figures have been described in the annual report of CITR 15.

Results

There were sufficient data available to report on 1017 islet preparations used for clinical allogeneic transplantation. These 1017 islet preparations were infused into 537 recipients: 167 (31%) patients received single infusion, 270 (50%) received two infusions, 92 (17%) received three infusions, 7 (1%) received four infusions, and 1 patient received six infusions. For each infusion event, a single donor pancreas was used 90% of the time, two pancreata were pooled for 9.3% of infusions and islets from three donors were combined for a single infusion in five instances.

Changes in donor and islet isolation by era

Table 1 shows the various characteristics of the 1017 donors and infusions, organized for comparison by era of 1999–2002, 2003–2006 and 2007–2010. Significant increase in body weight, BMI, use of steroid and insulin during treatment at last admission use were observed among donor characteristics (p < 0.001, <0.001, <0.05 and <0.05, Table 1). Pancreas preservation method significantly changed during the study period (p < 0.001, Table 2); the ratio of University of Wisconsin solution (UW) only and two layer method (TLM) decreased in 2007–2010 compared to the earlier eras (p < 0.001, Table 2). Time from death to cross-clamp, time from pancreas recovery to transplant and death to transplant were significantly prolonged (p < 0.001, Table 2).

Table 1B.

Pancreas preservation and recovery

| Total (n = 1017) | Era | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 (n = 257) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | |||

| Procurement/transplant centers related, % (n) | 61.5 (n = 551) | 60.6 (n = 157) | 61.3 (n = 284) | 63.2 (n = 110) | |

| Pancreas preservation, % (n) | <0.001 | ||||

| UW only | 42.3 (n = 430) | 58.4 (n = 150) | 46 (n = 217) | 21.9 (n = 63) | |

| TLM only | 20.4 (n = 207) | 16.7 (n = 43) | 29.2 (n = 138) | 9 (n = 26) | |

| HTK only | 7 (n = 71) | 0 (n = 0) | 6.8 (n = 32) | 13.5 (n = 39) | |

| Celsior | 2.3 (n = 23) | 1.9 (n = 5) | 1.7 (n = 8) | 3.5 (n = 10) | |

| UW+TLM | 3.8 (n = 39) | 3.9 (n = 10) | 4.7 (n = 22) | 2.4 (n = 7) | <0.001 |

| Combinations/other | 4.8 (n = 49) | 4.7 (n = 12) | 4 (n = 19) | 6.3 (n = 18) | |

| Missing/unknown | 19.5 (n = 198) | 14.4 (n = 37) | 7.6 (n = 36) | 43.4 (n = 125) | |

| Time (hours) | |||||

| Admission to brain death | 50.3 ± 61.3 (n = 592) | 50 ± 57.3 | 51.4 ± 66.8 | 47.9 ± 51.1 | |

| Death to cross-clamp | 18.4 ± 8.3 (n = 766) | 16.4 ± 6.6 | 18.8 ± 8.6 | 19.8 ± 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Cross-clamp to pancreas recovery | 0.8 ± 1.1 (n = 627) | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | |

| Death to pancreas recovery | 18.7 ± 8.6 (n = 571) | 16.6 ± 6.9 | 19.2 ± 8.9 | 19.7 ± 9.2 | |

| Cold ischemia time | 7.6 ± 6.1 (n = 775) | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 7.2 ± 3.2 | 9.3 ± 11.6 | |

| Pancreas recovery to transplant | 33.5 ± 20.5 (n = 629) | 25.3 ± 18.5 | 33.3 ± 20.3 | 41.4 ± 20.0 | <0.001 |

| Death to transplant | 52.9 ± 23.6 (n = 796) | 43.7 ± 22.1 | 52.9 ± 23.4 | 63.1 ± 21.6 | <0.001 |

| Percentage excluding missing cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 819) | Era | p-Value | |||

| 1999–2002 (n = 220) | 2003–2006 (n = 436) | 2007–2010 (n = 164) | |||

| Pancreas preservation, % (n) | <0.001 | ||||

| UW only | 52.5% | 68.2% | 49.8% | 38.4% | |

| TLM only | 25.3% | 19.5% | 31.7% | 15.9% | |

| HTK only | 8.7% | 0.0% | 7.3% | 23.8% | |

| Celsior | 2.8% | 2.3% | 1.8% | 6.1% | |

| UW+TLM | 4.8% | 4.5% | 5.0% | 4.9% | |

| Combinations/other | 6.0% | 5.5% | 4.4% | 11.0% | |

HTK, histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate; TLM, two layer method; UW, University of Wisconsin solution.

The pancreas digestion enzyme changed significantly during the study period; NB1 collagenase has primarily replaced Liberase HI in the most recent era (p < 0.001, Table 3). The proportion of in vitro culture more than 6 h has increased significantly over the era (p < 0.001).

Table 1C.

Islet processing

| Total (n = 1017) | Era | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 (n = 257) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | |||

| Digestion enzyme, % (n) | |||||

| Collagenase | <0.001 | ||||

| Liberase HI alone | 57.8 (n = 588) | 91.4 (n = 235) | 71.6 (n = 338) | 5.2 (n = 15) | |

| Serva NB1 alone | 9.3 (n = 95) | – | 3.6 (n = 17) | 27.1 (n = 78) | |

| ServaGMPColl+ServaNeutProtease | 4.7 (n = 48) | – | – | 16.7 (n = 48) | |

| CollagenaseP alone | 1.5 (n = 15) | 0.8 (n = 2) | 2.5 (n = 12) | 0.3 (n = 1) | |

| Liberase MTF | 0.3 (n = 3) | – | – | 1 (n = 3) | |

| Liberase-collagenase blend | 4.7 (n = 48) | – | 9.7 (n = 46) | 0.7 (n = 2) | |

| Other/other combination | 5.9 (n = 60) | 0.4 (n = 1) | 7.2 (n = 34) | 8.7 (n = 25) | |

| Not yet reported | 15.7 (n = 160) | 7.4 (n = 19) | 5.3 (n = 25) | 40.3 (n = 116) | |

| Thermolysin (in addition to other) | 7.3 (n = 63) | – | 12.5 (n = 56) | 4 (n = 7) | |

| Pulmozyme (in addition to other) | 45.4 (n = 391) | 14.7 (n = 35) | 54.6 (n = 245) | 63.4 (n = 111) | <0.001 |

| Purification gradient type, % (n) | |||||

| Discontinuous | 5.8 (n = 49) | 9.8 (n = 21) | 5.9 (n = 26) | 1.1 (n = 2) | |

| Continuous | 83.8 (n = 704) | 77.7 (n = 167) | 82.4 (n = 361) | 94.1 (n = 176) | |

| Both | 10.2 (n = 86) | 12.6 (n = 27) | 11.4 (n = 50) | 4.8 (n = 9) | |

| Islet culture (hours) | |||||

| Culture time (0-max) | 17.7 ± 18.4 (n = 777) | 11.9 ± 18.1 | 18 ± 17.9 | 24.7 ± 17.5 | |

| Cultured ≥6 h, % (n) | 26.5 (n = 269) | 14.4 (n = 37) | 14.4 (n = 68) | 56.9 (n = 164) | <0.001 |

| Percentage excluding missing cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 857) | Era | ||||

| 1999–2002 (n = 238) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | p-Value | ||

| Digestion enzyme, % (n) | |||||

| Collagenase | <0.001 | ||||

| Liberase HI alone | 68.6% | 98.7% | 75.6% | 8.7% | |

| Serva NB1 alone | 11.1% | 0.0% | 3.8% | 45.3% | |

| ServaGMPColl+ServaNeutProtease | 5.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 27.9% | |

| CollagenaseP alone | 1.8% | 0.8% | 2.7% | 0.6% | |

| Liberase MTF | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.7% | |

| Liberase-collagenase blend | 5.6% | 0.0% | 10.3% | 1.2% | |

| Other/other combination | 7.0% | 0.4% | 7.6% | 14.5% | |

IEQ per islet particle number and IEQ infused were significantly higher during 2007–2010 when compared to 1999–2002 (p < 0.001 and <0.05, respectively, Table 4) although no significant change in total IEQ at particle count (completion of isolation) was seen. IEQ at count and IEQ infused correlated strongly with each other (r = 0.93, p < 0.0001, Figure S1). Purity of islets and the number of total β cells in 2007–2010 were significantly higher than the previous years (p < 0.01 and <0.05, respectively, Table 4). The stimulation index and viability declined over the periods (p < 0.001 and <0.01, respectively) but remained above 2.7 and 90.2%, respectively.

The analysis of donor and isolation characteristics compared by continent (North America vs. European and Australian sites) and by type of transplantation (ITA vs. IAK/SIK) are shown in Tables S1–S5. Briefly, significant differences were seen in the following variables when the data were stratified by continent (p < 0.05): donor body weight, BMI, maximum blood glucose, donor steroid therapy, insulin therapy, transplant-center related pancreas procurement, pancreas preservation, time from death to cross-clamp, cross-clamp to pancreas recovery, death to transplant, pancreas digestion enzyme, islet culture over 6 h, total IEQ at count, IEQ/particle count, IEQ infused, purity, stimulation index, total insulin content of islets, number of islet infusion sequence and the number of total donor(s) per infusion. Analyzed by ITA versus IAK/SIK, the following variables showed significant differences: donor body weight, BMI, cause of death, HbA1c, donor steroid therapy, insulin therapy, time from death to cross-clamp, death to pancreas recovery, pancreas digestion enzyme, purification method, total IEQ at count, IEQ infused, packed cell volume, purity and ratio of embedded islets (Tables S1–S5).

Table 1E.

Islet infusion

| Total (n = 1017) | Era | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2002 (n = 257) | 2003–2006 (n = 472) | 2007–2010 (n = 288) | |||

| Recipient infusion sequence #, % (n) | <0.05 | ||||

| 1st | 52.8 (n = 537) | 62.3 (n = 160) | 46 (n = 217) | 55.6 (n = 160) | |

| 2nd | 36.4 (n = 370) | 31.9 (n = 82) | 39.2 (n = 185) | 35.8 (n = 103) | |

| 3rd | 9.8 (n = 100) | 5.4 (n = 14) | 14 (n = 66) | 6.9 (n = 20) | |

| 4th–6th | 1 (n = 10) | 0.4 (n = 1) | 0.8 (n = 4) | 1.6 (n = 5) | |

| Total donors/infusion, % (n) | |||||

| 1 | 90.2 (n = 917) | 89.9 (n = 231) | 88.6 (n = 418) | 93.1 (n = 268) | |

| 2 | 9.3 (n = 95) | 9.3 (n = 24) | 11.2 (n = 53) | 6.3 (n = 18) | |

| 3 | 0.5 (n = 5) | 0.8 (n = 2) | 0.2 (n = 1) | 0.7 (n = 2) | |

| Any positive crossmatch, % (n) | 3.1 (n = 20) | 0.8 (n = 1) | 3.8 (n = 12) | 3.7 (n = 7) | |

Variables associated with islet product characteristics

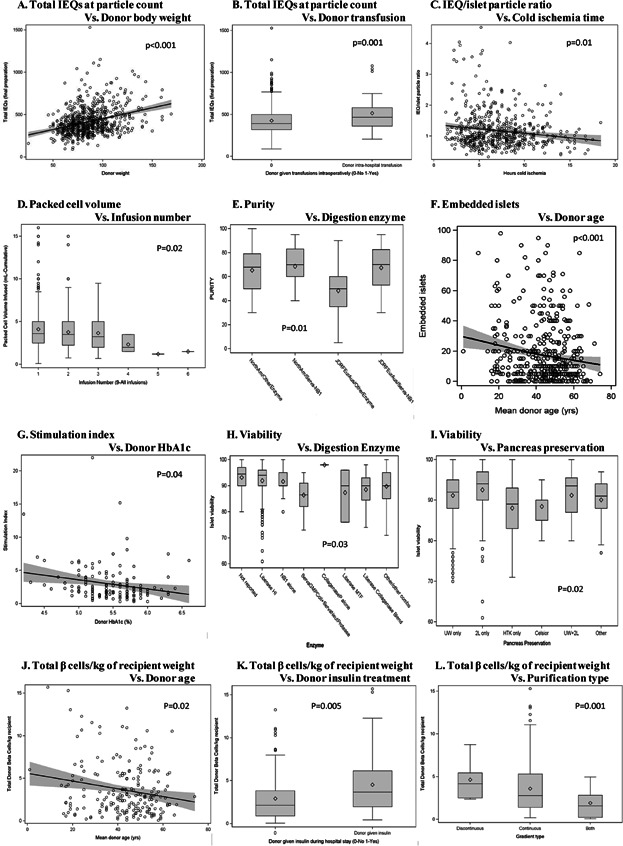

The donor and isolation factors associated with islet product characteristics are shown in Table 6 and Figure 1. Total IEQs at particle count was remarkably associated with donor body weight (Figure 1A), BMI, donor steroid therapy at last admission and blood transfusion (Figure 1B), time from death to cross-clamp, total number of donors per infusion and continent. IEQ/particle count was associated with donor BMI, donor steroid therapy, CIT (Figure 1C), time from death to cross-clamp, pancreas digestion enzymes, era and continent. Packed cell volume correlated negatively with the number of islet infusions sequence (Figure 1D). Islet purity was associated with donor steroid therapy, time from death to cross-clamp, pancreas digestion enzymes (Figure 1E) and continents. The proportion of embedded islets correlated negatively with donor age (Figure 1F). Stimulation index correlated negatively with donor HbA1c (Figure 1G). Viability was negatively associated with Liberase HI (Figure 1H), and associated with pancreas preservation method (Figure 1I). Total β cell number per kilograms of recipient body weight correlated negatively with donor age (Figure 1J), cause of death, steroid and insulin therapy (Figure 1K), purification methods (Figure 1L), islet culture time and era. Total insulin content correlated negatively with donor steroid therapy at the last admission, and correlated positively with total number of donors per infusion and continents. Significant changes were observed in endotoxin content during the analysis period; however, wide variation in data was also noted. This difference observed between sites from different continents could be due to changes in the methodology.

Table 2.

Correlations between donor, procurement, processing characteristics (“factors”; rows) and islet product criteria (columns) in 1017 islet preparations of clinical allogeneic transplantation in CITR, 1999–2010

| Category | Factors | IEQ at count (1000s) | IEQ/particle count ratio | Purity (%) | Embedded islets (%) | Viability (%) | Total beta cells/kg recipient | Total insulin content (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor characteristics | Age (years) | −0.183 | −0.195 | |||||

| <0.0001 | 0.0052 | |||||||

| 480 | 204 | |||||||

| Donor BMI | 0.265 | 0.193 | ||||||

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 733 | 620 | |||||||

| Trauma death (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.198 | |||||||

| 0.0038 | ||||||||

| 212 | ||||||||

| Donor given steroids during hospital stay (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.161 | 0.265 | 0.172 | 0.245 | −0.257 | |||

| 0.001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0613 | 0.0079 | ||||

| 417 | 309 | 487 | 59 | 106 | ||||

| Donor given insulin during hospital stay (0 = no, 1 = yes) | 0.255 | |||||||

| 0.0005 | ||||||||

| 184 | ||||||||

| Pancreas preservation and recovery | Hours from death to cross-clamp | 0.157 | 0.189 | 0.156 | ||||

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 653 | 548 | 653 | ||||||

| Islet processing | Liberase HI | −0.18454 | 0.171 | |||||

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 639 | 743 | |||||||

| Serva NB1 | 0.2338 | 0.170 | ||||||

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| 639 | 762 | |||||||

| Hours culture time | 0.287 | |||||||

| <0.0001 | ||||||||

| 219 | ||||||||

| Islet infusion | Total donors (1, 2, 3) | 0.182 | 0.203 | |||||

| <.0001 | 0.0013 | |||||||

| 773 | 247 | |||||||

| Era (1 = 1999–2002, 2 = 2003–2006, 3 = 2007–2010) | 0.144 | 0.164 | ||||||

| 0.0002 | 0.0154 | |||||||

| 655 | 219 | |||||||

| Continent (0 = North America, 1 = Europe/Australia) | −0.265 | −0.199 | −0.319 | 0.189 | ||||

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0029 | |||||

| 773 | 655 | 770 | 247 |

CITR, Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry; IEQ, islet equivalent.

Each cell describes, from top to bottom: correlation coefficient, Pr{Rho = 0|H0} number of observations.

Figure 1.

Factors significantly associated with islet product characteristics. (A) Total islet equivalents (IEQs) at particle count versus donor body weight. (B) Total IEQs at particle count versus donor transfusion. (C) IEQ/islet particle ratio versus CIT, cold ischemia time (CIT). (D) Packed cell volume versus infusion number. (E) Purity versus digestion enzyme. (F) Embedded islets versus donor age. (G) Stimulation index versus donor HbA1c. (H) Viability versus digestion enzyme. (I) Viability versus pancreas preservation. (J) Total β cells/kg of recipient weight versus donor age. (K) Total β cells/kg of recipient weight versus donor insulin treatment. (L) Total β cells/kg of recipient weight versus purification type.

Donor and islet product characteristics associated with clinical outcomes

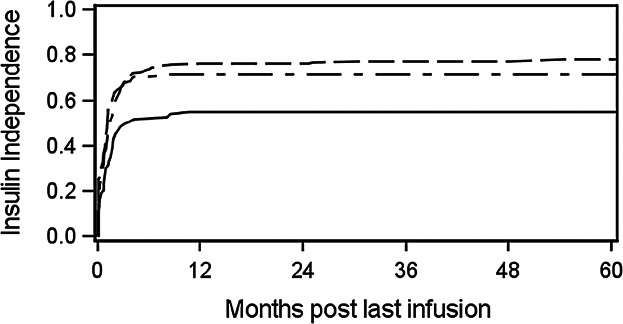

Of all the donor characteristics and islet product criteria assessed for their association with primary clinical end points, the only factor significantly associated with any primary outcome was total IEQs infused on achievement of insulin independence over one to several infusions (Figure 2): when at least 600 000 total IEQs were infused, 75–80% of recipients achieved insulin independence compared to 55% achieving insulin independence with <600 000 IEQs infused (hazard ratio = 1.215, p = 0.035), regardless of the number of infusions. (Over the entire CITR period, of the 537 recipients, 31% received one infusion, 50% received two infusions and 17% received three infusions.) No other donor or islet product characteristics were related to this or any other clinical outcome including retention of insulin independence after achievement, or retention of fasting C-peptide >0.3 ng/mL (indicating a functioning graft).

Figure 2.

Effect of total islet equivalents (1000 s) infused, over one to several infusions, on achievement of insulin independence (≥14 days) post–last infusion in clinical islet transplantation (hazard ratio = 1.215, p = 0.035; solid line: <600; dashes: 600 to <1000; dashes-dots: >1000).

Discussion

This report represents a comprehensive analysis of clinical-grade islet products from a total of 1017 isolations performed at CITR-participating North American, European and Australian centers. We found a significant increase in IEQs infused in the most recent era and that higher islet mass transplanted was independently associated with the clinical outcome of insulin independence rate. While there are some improvements in islet product criteria for islet transplantation, these criteria have been set so stringently high that it is not possible to compare clinical outcomes across low-, medium- and high-quality islet preparations, thus curtailing our ability to definitively state which specific product criteria influence clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, the improvements noted here in pancreatic islet yield and isolation in this duodecennium have paralleled the notable improvements in clinical outcomes of islet transplantation for the same period 14. Despite the strengths of this study including the largest collection of clinical islets for transplantation ever reported on, limitations are: nonuniformity of islet procurement and preparation methods across several nations in three continents and over a 12-year period; an estimated 80% availability of relevant data in the pertinent geographic regions and calendar time frame; a lack of low- to medium-quality islets for statistical comparison of outcomes.

Along with increasing IEQs infused by era, donor body weight, BMI and the frequency of steroid and insulin use in the last admission also showed significant gains by era 14. It is expected that higher body weight or BMI correlates with higher islet yield 1,2,4,7,11–13. This could be due to increased islet mass 1,11, larger islet size 11 or more efficient digestion of fat-infiltrated pancreata 1. Some studies have found BMI to be a positive predictor of islet viability and insulin secretion 1,16 but we could not confirm those results here. Surprisingly, we found that as donor BMI rose, so did the infused endotoxin content. This could be a confounder of the data set in which endotoxin values were generally higher at North American sites, where average BMI has increased over time disproportionately to non-North American JDRF sites.

Reports on age-based yield effects in the literature have been mixed, associating younger donors with higher yields 9,12,13, lower yields 5 or no effect 10. We found no direct correlation of donor age to IEQ-based measures. It is likely that the contradictory results of these studies are tied to varying degrees of postpurification recovery, as the correlation between young donor age and a high % of embedded islets, such as we observed here, is well established 2,9,12,17,18. A second confounding factor may be the variability in definition between “young” and “old.” Another study has instituted a maximum donor age of 50 years, which aligns with a recent observation that the most significant differences arise from segregating donor data above and below 45 years old 10. Given the clear benefits of lower donor age on islet functionality, future research efforts should focus on minimizing the loss of embedded islets during purification.

Apart from inherent donor characteristics, the data show a trend toward more intensive treatment—that is, more frequent use of steroids and insulin—during the terminal hospital stay, potentially representing recognition of benefits to subsequently donated tissue 7. Although some investigators have suggested that donor fluid resuscitation or blood transfusion may be detrimental to islet yield 6,13, we found intraoperative transfusions correlated with higher IEQs at particle count. Donor steroid treatment pushed yields higher, which confirms similar results of an earlier study in which steroid use was associated with twice as many successful clinical isolations as nonsteroid treated donors 7. On the other hand, steroid use, in this investigation, was also correlated to reduced insulin and elevated endotoxin in the final islet product. The CITR database provided information on donor insulin treatment, which has not been previously considered as a clinical islet isolation variable. Nevertheless, we found that insulin use was correlated with higher beta cell/kg recipient. This finding is supported by preclinical research suggesting that insulin treatment can promote or maintain islet beta cell mass in rodents 19,20. The impact of donor vasopressor treatment is unclear and has been correlated to reduced yield 2, elevated yield 7 or no effect 9,13. We found no significant impact of vasopressors on any of our outcome measures but it is conceivable that a more specific sub-categorization may be necessary to resolve this question.

Since its introduction more than two decades ago, TLM for packaging and transporting the pancreas to an isolation-capable facility has been vigorously debated. Early experiments on canine pancreata suggested that a bottom layer of oxygenated perfluorochemical could promote cellular respiration in otherwise ischemic tissue and thereby enhance the yield and viability of recovered islets 21,22. Although clinical experiments initially supported these claims 23, a series of subsequent investigations found no benefit of TLM over simple UW cold storage 24–28 and modern literature reviews have tended to limit the benefits of TLM to long-distance travel 12,29. The rise and fall of TLM popularity is reflected here in its peak usage between 2004 and 2006 with a significant decline into the modern era. We did not find any full group independent effects, but a small percentage (3%) of cases did see a benefit of TLM on total IEQs, potentially owing to longer transport conditions or to the increased attention and experience demanded of procurement staff to properly implement the technique. Given the cost and difficulty of the procedure and at least one study where TLM packaging was actively detrimental to postculture islet recovery 30, it seems appropriate that the trend toward simple cold storage continues. In that context, UW had historically dominated the choice of cold storage solution for the human pancreas but the less expensive histadine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) has seen increasing use in North America. Several studies have reported no difference between UW and HTK on isolation outcome 1,11,25,31 but a few have correlated HTK use to diminished graft survival 32 and reduced yield 13. The CITR data support the finding that HTK solution was associated with reduced islet viability and suggests that a thorough and specific analysis of HTK's influence on clinical outcomes is warranted.

Changes over time in postisolation processing seem largely focused on islet culture, which has increased dramatically in the last decade. Culturing islets provides a flexible time window for quality control testing, travel accommodations for recipients, recipient pretreatment with immunosuppression to avoid cytokine associated islet injury and the potential for storing or pooling islets for infusion into a compatible recipient 30,33,34. The benefits of culture to reducing immunogenicity have been known for some time 33,35–39 but culturing has also been found to improve islet morphology, increase pellet purity and viability while reducing total tissue volume 30,34. On the other hand, major islet losses can occur even over short periods 30,33,34 as well as increased fragmentation 30,33,40,41 and diminished endocrine function 30,33,34. We found that a greater number of culture hours boosted yield and endocrine composition, although the average period here (∼18 h) was significantly shorter than the time periods examined in the studies listed. Whether an infusion of short-term cultured islets results in a better clinical outcome than freshly isolated islets still remains unresolved 33,34. One promising future direction seems to be in the improvement of culture conditions to better promote islet survival and function. Fraker et al 42 have recently developed a culturing device with a perfluorohydrocarbone-silicone membrane that maintains a more physiological oxygen supply to the islets, minimizing overnight losses and boosting viability.

The unavailability of Liberase HI for clinical digestion due to FDA recommendation in 2007, has led to major changes in isolation and transplant activity around the world. Numerous studies have examined the differences between Liberase and its most common replacement, Serva NB1, but results have been consistently contradictory. Compared to Liberase, NB1 has been found to improve yield 12,16,43, reduce yield 44, encourage viability and endocrine function 43,44 or diminish it 45, and to shorten digestion time 11,16 or prolong it 45. There does appear to be general agreement that Liberase results in higher endotoxin content 44–46 and less product purity 44 than NB1, findings that we confirmed in this analysis. We also observed a clear differentiation on yield with Liberase and NB1 negatively and positively correlated to IEQ/particle ratio, respectively. Nevertheless, there is a growing trend towards the use of other digestion enzymes and combinations as various alternatives have become available. The University of Minnesota identified a higher proportion of intact C1 collagenase isoform in Liberase versus NB1, which could account for some of the negative reports on NB1 enzyme 47. It was subsequently shown that VitaCyte-HA collagenase contains the highest available intact C1 and when used in combination with NB1 neutral protease doubled the percentage of successful clinical islet isolations 47,48.

Not surprisingly, the use of a discontinuous gradient for isopycnic density purification has almost disappeared, given the technical limitations of this system and its negative impact on yield 49,50. Accordingly, we correlated a continuous gradient to higher particle count but more interestingly, we found that the use of a discontinuous gradient appeared to increase the beta cell content of the final product. This finding is consistent with another study showing improved islet morphology 4 to suggest that an investigation of the circumstantial benefits of discontinuous gradient purification may be warranted before the technique is altogether abandoned. On the other hand, the necessity of any purification procedure continues to be debated, especially given the difficulty in obtaining critical minimum islet mass from deceased donors and the reported success of nonpurified islets in autologous islet transplant recipients 51.

Major differences of the present study from previous reports of pancreatic islet isolation include analysis of only clinical-grade islet products, changes over time and data reported from multiple countries on three different continents. Kaddis et al reported their analyses on donor and isolation characteristics of both clinical and research grade islets based on collaboration of multiple islet centers in North America (n of isolations = 1023), revealing that donor age, BMI, CIT, liver/pancreas enzyme, pancreas appearance and preservation method were independently related to islet isolation success 13,52. In the present study focusing on clinical-grade islet products, the primary end point of islet yield was correlated with donor BMI, steroid therapy at terminal hospital stay, hours between death and cross-clamp, number of donors and continent. These findings confirm that donor and/or selection criteria for clinical isolation are well established.

Overall, findings in the present report with regard to donor characteristics of age and BMI are in agreement with previously published results. Evidence continues to build that simple cold storage in UW solution may be the best packaging method if applied with due care but the benefits of a postisolation culture period may be outweighed by losses if more physiological culture conditions are not developed and adopted. The debate over Serva NB1 as a substitute for Liberase HI continues but although the present results suggest general benefits from using NB1, the movement toward alternate enzymes and combinations may soon render this argument moot. Finally, purification technique seems to warrant additional study both to improve the recovery of high-functioning but frequently embedded islets from young donors and to evaluate whether some surprising viability benefits of a discontinuous density gradient justify the use of this procedure in specific situations.

Future directions to improve islet isolation outcomes include modification of pancreas preservation 53, development of new combinations of collagenase or neutral protease 48, optimization of digestion 54,55 and enhancing purification 56. Attempts to measure islet quantity and quality in objective ways such as digital image analysis, oxygen consumption rate and islet biomarkers should translate into improved clinical efficacy through more precise data analysis 24,57,58. The CITR should continue capturing these developments and trends. The ultimate success of any islet isolation and transplantation is, of course, in the benefit to the recipient. The range of measures pertaining to transplant outcome such as euglycemia will be the subject of a forthcoming analysis.

Acknowledgments

The CITR is funded by the NIDDK, National Institutes of Health and by a supplemental grant from the JDRF International. Additional data were made available through cooperative agreements with the U.S. United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), Alexandria, Virginia, the Administrative and Bioinformatics Coordinating Center of the City of Hope, Duarte, California (1999–2009) and the NIDDK-sponsored CIT (www.citisletstudy.org), coordinated by the University of Iowa Clinical Trials and Data Management Center (2008–present).

Glossary

- BMI

body mass index

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- CITR

Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry

- HTK

histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate

- IAK

islet after kidney transplantation

- IEQ

islet equivalent

- ITA

islet transplant alone

- JDRF

Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation

- NIDDK

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- SIK

simultaneous islet and kidney transplantation

- TLM

two layer method

- UW

University of Wisconsin solution

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Distribution of islet yields processed and infused. Percent distribution of total islet yield (A) and the correlation between those at count and infusion (B) are shown. Data are based on 1017 clinical products in NIDDK-sponsored North American and JDRF European and Australian CITR sites participating in the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry, 1999–2010. Linear regression (r = 0.93, p < 0.0001) is shown (B).

Donor characteristics.

Table S2: Pancreas preservation and recovery.

Table S3: Islet processing.

Table S4: Islet product characteristics.

Table S5: Islet infusion.

References

- 1.Brandhorst H, Brandhorst D, Hering BJ, Federlin K, Bretzel RG. Body mass index of pancreatic donors: A decisive factor for human islet isolation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1995;103:23–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211388. (Suppl 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakey JR, Warnock GL, Rajotte RV, et al. Variables in organ donors that affect the recovery of human islets of Langerhans. Transplantation. 1996;61:1047–1053. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199604150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goto M, Johansson U, Eich TM, et al. Key factors for human islet isolation and clinical transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1315–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nano R, Clissi B, Melzi R, et al. Islet isolation for allotransplantation: Variables associated with successful islet yield and graft function. Diabetologia. 2005;48:906–912. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1725-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SC, Han DJ, Kang CH, et al. Analysis on donor and isolation-related factors of successful isolation of human islet of Langerhans from human cadaveric donors. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3402–3403. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Gorman D, Kin T, Murdoch T, et al. The standardization of pancreatic donors for islet isolations. Transplantation. 2005;80:801–806. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000172216.47547.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponte GM, Pileggi A, Messinger S, et al. Toward maximizing the success rates of human islet isolation: Influence of donor and isolation factors. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:595–607. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh A, Kin T, Imes S, Shapiro AM, Senior P. Islets isolated from donors with elevated HbA1c can be successfully transplanted. Transplantation. 2008;86:1622–1624. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818c2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Matsumoto S, Okitsu T, et al. Analysis of donor- and isolation-related variables from non-heart-beating donors (NHBDs) using the Kyoto islet isolation method. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:649–656. doi: 10.3727/096368908786092711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niclauss N, Bosco D, Morel P, et al. Influence of donor age on islet isolation and transplantation outcome. Transplantation. 2011;91:360–366. doi: 10.1097/tp.0b013e31820385e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Daneilson KK, Ropski A, et al. Systematic analysis of donor and isolation factor's impact on human islet yield and size distribution. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:2323–2333. doi: 10.3727/096368912X662417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilling DE, Bouwman E, Terpstra OT, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. Effects of donor-, pancreas-, and isolation-related variables on human islet isolation outcome: A systematic review. Cell Transplant. 2014;23:921–928. doi: 10.3727/096368913X666412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaddis JS, Danobeitia JS, Niland JC, Stiller T, Fernandez LA. Multicenter analysis of novel and established variables associated with successful human islet isolation outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:646–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02962.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton FB, Rickels MR, Alejandro R, et al. Improvement in outcomes of clinical islet transplantation: 1999–2010. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1436–1445. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center CC. Seventh annual report of the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry. 2011. Available at: http://www.citregistry.org/. Accessed February 12, 2014.

- 16.Sabek OM, Cowan P, Fraga DW, Gaber AO. The effect of isolation methods and the use of different enzymes on islet yield and in vivo function. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:785–792. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Socci C, Davalli AM, Vignali A, et al. A significant increase of islet yield by early injection of collagenase into the pancreatic duct of young donors. Transplantation. 1993;55:661–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricordi C. Islet transplantation: A brave new world. Diabetes. 2003;52:1595–1603. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Movassat J, Saulnier C, Portha B. Insulin administration enhances growth of the beta-cell mass in streptozotocin-treated newborn rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:1445–1452. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.9.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitamura T, Nakae J, Kitamura Y, et al. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 links insulin signaling to Pdx1 regulation of pancreatic beta cell growth. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1839–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda Y, Kawamura T, Suzuki Y, Fujiwara H, Yamamoto K, Saitoh Y. A new, simple method for cold storage of the pancreas using perfluorochemical. Transplantation. 1988;46:457–460. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198809000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanioka Y, Sutherland DE, Kuroda Y, et al. Excellence of the two-layer method (University of Wisconsin solution/perfluorochemical) in pancreas preservation before islet isolation. Surgery. 1997;122:435–441. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90037-4. discussion 441–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto S, Rigley TH, Qualley SA, Kuroda Y, Reems JA, Stevens RB. Efficacy of the oxygen-charged static two-layer method for short-term pancreas preservation and islet isolation from nonhuman primate and human pancreata. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:769–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papas KK, Colton CK, Nelson RA, et al. Human islet oxygen consumption rate and DNA measurements predict diabetes reversal in nude mice. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:707–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noguchi H, Ueda M, Hayashi S, et al. Comparison of M-Kyoto solution and histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate solution with a trypsin inhibitor for pancreas preservation in islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:655–658. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000277625.42147.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto S, Noguchi H, Hatanaka N, et al. Estimation of donor usability for islet transplantation in the United States with the Kyoto islet isolation method. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:549–556. doi: 10.1177/096368970901805-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kin T, Mirbolooki M, Salehi P, et al. Islet isolation and transplantation outcomes of pancreas preserved with University of Wisconsin solution versus two-layer method using preoxygenated perfluorocarbon. Transplantation. 2006;82:1286–1290. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244347.61060.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caballero-Corbalán J, Eich T, Lundgren T, et al. No beneficial effect of two-layer storage compared with UW-storage on human islet isolation and transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:864–869. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000284584.60600.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin H, Matsumoto S, Klintmalm GB, De Vol EB. A meta-analysis for comparison of the two-layer and university of Wisconsin pancreas preservation methods in islet transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:1127–1137. doi: 10.3727/096368910X544942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kin T, Senior P, O'Gorman D, Richer B, Salam A, Shapiro AM. Risk factors for islet loss during culture prior to transplantation. Transpl Int. 2008;21:1029–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salehi P, Hansen MA, Avila JG, et al. Human islet isolation outcomes from pancreata preserved with histidine-tryptophan ketoglutarate versus University of Wisconsin solution. Transplantation. 2006;82:983–985. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232310.49237.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart ZA, Cameron AM, Singer AL, Dagher NN, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate (HTK) is associated with reduced graft survival in pancreas transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:217–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaber AO, Fraga DW, Callicutt CS, Gerling IC, Sabek OM, Kotb MY. Improved in vivo pancreatic islet function after prolonged in vitro islet culture. Transplantation. 2001;72:1730–1736. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, Jackson A, et al. Fresh islets are more effective for islet transplantation than cultured islets. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:517–523. doi: 10.3727/096368911X605439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kedinger M, Haffen K, Grenier J, Eloy R. In vitro culture reduces immunogenicity of pancreatic endocrine islets. Nature. 1977;270:736–738. doi: 10.1038/270736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lacy PE, Davie JM, Finke EH. Prolongation of islet allograft survival following in vitro culture (24 degrees C) and a single injection of ALS. Science. 1979;204:312–313. doi: 10.1126/science.107588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lafferty KJ, Prowse SJ, Simeonovic CJ, Warren HS. Immunobiology of tissue transplantation: A return to the passenger leukocyte concept. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:143–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cosimi S, Marchetti P, Giannarelli R, et al. Preparation and long-term storage by culture or cryopreservation of purified bovine pancreatic islets. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markmann JF, Tomaszewski J, Posselt AM, et al. The effect of islet cell culture in vitro at 24 degrees C on graft survival and MHC antigen expression. Transplantation. 1990;49:272–277. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brendel MD, Kong SS, Alejandro R, Mintz DH. Improved functional survival of human islets of Langerhans in three-dimensional matrix culture. Cell Transplant. 1994;3:427–435. doi: 10.1177/096368979400300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korbutt GS, Pipeleers DG. Cold-preservation of pancreatic beta cells. Cell Transplant. 1994;3:291–297. doi: 10.1177/096368979400300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fraker CA, Cechin S, Alvarez-Cubela S, et al. A physiological pattern of oxygenation using perfluorocarbon-based culture devices maximizes pancreatic islet viability and enhances beta-cell function. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:1723–1733. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bucher P, Mathe Z, Bosco D, et al. Serva collagenase N B1: A new enzyme preparation for human islet isolation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1143–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandhorst H, Friberg A, Nilsson B, et al. Large-scale comparison of Liberase HI and collagenase NB1 utilized for human islet isolation. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:3–8. doi: 10.3727/096368909X477507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iglesias I, Valiente L, Shiang KD, Ichii H, Kandeel F, Al-Abdullah IH. The effects of digestion enzymes on islet viability and cellular composition. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:649–655. doi: 10.3727/096368911X623826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balamurugan AN, He J, Guo F, et al. Harmful delayed effects of exogenous isolation enzymes on isolated human islets: Relevance to clinical transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2671–2681. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balamurugan AN, Breite AG, Anazawa T, et al. Successful human islet isolation and transplantation indicating the importance of class 1 collagenase and collagen degradation activity assay. Transplantation. 2010;89:954–961. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d21e9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balamurugan AN, Loganathan G, Bellin MD, et al. A new enzyme mixture to increase the yield and transplant rate of autologous and allogeneic human islet products. Transplantation. 2012;93:693–702. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318247281b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson GS, Chadwick DR, Contractor H, James RF, London NJ. The optimization of large-scale density gradient isolation of human islets. Acta Diabetol. 1993;30:93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00578221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei GH, Sun WP, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of continuous and discontinuous density gradient centrifugation for purification of human pancreatic islets. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27:1352–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webb MA, Dennison AR, James RF. The potential benefit of non-purified islets preparations for islet transplantation. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2012;28:101–114. doi: 10.5661/bger-28-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaddis JS, Olack BJ, Sowinski J, Cravens J, Contreras JL, Niland JC. Human pancreatic islets and diabetes research. JAMA. 2009;301:1580–1587. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimoda M, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, et al. Improvement of collagenase distribution with the ductal preservation for human islet isolation. Islets. 2012;4:130–137. doi: 10.4161/isl.19255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friberg AS, Korsgren O, Hellgren M. A vast amount of enzyme activity fails to be absorbed within the human pancreas: Implications for cost-effective islet isolation procedures. Transplantation. 2013;95:e36–e38. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318283a859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Gorman D, Kin T, Pawlick R, Imes S, Senior PA, Shapiro AM. Clinical islet isolation outcomes with a highly purified neutral protease for pancreas dissociation. Islets. 2013;5:111–115. doi: 10.4161/isl.25222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stahle M, Honkanen-Scott M, Ingvast S, Korsgren O, Friberg AS. Human islet isolation processing times shortened by one hour: Minimized incubation time between tissue harvest and islet purification. Transplantation. 2013;96:e91–e93. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000437562.31212.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niclauss N, Sgroi A, Morel P, et al. Computer-assisted digital image analysis to quantify the mass and purity of isolated human islets before transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86:1603–1609. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818f671a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itoh T, Takita M, SoRelle JA, et al. Correlation of released HMGB1 levels with the degree of islet damage in mice and humans and with the outcomes of islet transplantation in mice. Cell Transplant. 2012;21:1371–1381. doi: 10.3727/096368912X640592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Distribution of islet yields processed and infused. Percent distribution of total islet yield (A) and the correlation between those at count and infusion (B) are shown. Data are based on 1017 clinical products in NIDDK-sponsored North American and JDRF European and Australian CITR sites participating in the Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry, 1999–2010. Linear regression (r = 0.93, p < 0.0001) is shown (B).

Donor characteristics.

Table S2: Pancreas preservation and recovery.

Table S3: Islet processing.

Table S4: Islet product characteristics.

Table S5: Islet infusion.