Abstract

Background

Vietnamese-American women underutilize breast cancer screening.

Design

An RCT was conducted comparing the effect of lay health workers (LHWs) and media education (ME) to ME alone on breast cancer screening among these women.

Setting/participants

Conducted in California from 2004 to 2007, the study included 1100 Vietnamese-American women aged ≥40 years who were recruited through LHW social networks. Data were analyzed from 2007 to 2009.

Intervention

Both groups received targeted ME. The intervention group received two LHW educational sessions and two telephone calls.

Main outcome measures

Change in self-reported receipt of mammography ever, mammography within 2 years, clinical breast examination (CBE) ever, or CBE within 2 years.

Results

The LHW+ME group increased receipt of mammography ever and mammography in the past 2 years (84.1% to 91.6% and 64.7% to 82.1%, p<0.001) while the ME group did not. Both ME (73.1% to 79.0%, p<0.001) and LHW+ME (68.1% to 85.5%, p<0.001) groups increased receipt of CBE ever, but the LHW+ME group had a significantly greater increase. The results were similar for CBE within 2 years. In multivariate analyses, LHW+ME was significantly more effective than ME for all four outcomes, with ORs of 3.62 (95% CI=1.35, 9.76) for mammography ever; 3.14 (95% CI=1.98, 5.01) for mammography within 2 years; 2.94 (95% CI=1.63, 5.30) for CBE ever; and 3.04 (95% CI=2.11, 4.37) for CBE within 2 years.

Conclusions

Increased breast cancer screening by LHWs among Vietnamese-American women. Future research should focus on how LHWs work and whether LHW outreach can be disseminated to other ethnic groups.

Background

Vietnamese Americans constitute the second fastest growing Asian group in the U.S.1 Approximately two thirds are foreign-born.2–5 Limited English proficiency, health beliefs, lack of health knowledge, lack of healthcare access, and difficulties in physician–patient communication are important barriers faced by this population.4

Breast cancer incidence is rising among Vietnamese American women, for whom it is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third-leading cause of cancer death (following lung and liver cancer).6,7 These women have breast cancer diagnosed at more advanced stages and experience greater consequent mortality than non-Hispanic white women.8,9 These disparities are in part attributable to lower rates of cancer screening. In California, 69% of eligible Vietnamese women reported having a mammogram in the past 2 years in 2001, and 86% reported ever having had one (versus 93% of non-Hispanic whites) in 2003.10,11 More recent unpublished data from California show that, in 2005, 87% of Vietnamese women had ever had a mammogram and 73% had had one in the past 2 years (chis.ucla.edu).

One strategy to increase healthy behaviors has been to train lay health workers (LHWs) to promote health.12–16 LHWs are people who live in the community, who are selected by and accountable to it, and who work after receiving training.17,18 LHWs have natural cultural and linguistic competence, can be trained quickly to address a health issue, and, in a sustainable model, provide a pool of culturally competent educators who can be retrained to address a different issue.

Few rigorous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of LHW outreach (LHWO). A review of 43 studies conducted worldwide concluded that LHWO was effective for management of respiratory infections and malaria, and promotion of immunizations and breast cancer screening.19 Two U.S. reviews concluded that LHWO was effective in increasing knowledge and improving access, but that many studies had design flaws and that huge gaps remained in understanding how LHWO worked.17,20 Because LHWO requires major resource investments, more empirical evidence of its effectiveness is needed.21 Other research questions include which individuals may most benefit from it, whether it is more effective than other interventions, and whether there is an additive effect when it is combined with other interventions.

Previously, this investigator group has shown that a media-led education campaign led to an increase in knowledge about clinical breast examinations (CBEs) and planning to have CBEs and mammograms, although not in being up-to-date for either test, among Vietnamese-American women.22 More recently, this group showed that media-led education along with other community mobilization strategies increased receipt of Pap tests among these women5,23 and that LHWO, when combined with media education, had an additive effect on Pap testing compared to media education alone.24–26

Methods

This RCT was designed to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of an LHWO plus media education (LHWO+ME) strategy compared to the ME strategy alone to promote breast cancer screening with CBE and mammography among Vietnamese-American women; (2) determine if the interventions were more effective for screening test receipt ever or within 2 years; and (3) assess if knowledge mediated LHWO effectiveness. The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), IRB approved the research protocol.

Researchers at UCSF and Vietnamese-American community members formed a coalition to address cancer in 1999.23 The coalition partnered with five community-based organizations (CBOs) based in Santa Clara County CA, to conduct LHWO. The five CBOs carried out their work in a staggered fashion from September 2004 to March 2007, with each CBO conducting activities for 11 months. Each CBO hired a Vietnamese LHWO coordinator, who in turn recruited ten Vietnamese women to become LHWs (total=50 LHWs). Each LHW received $1500 for her work. Researchers trained LHWO coordinators and LHWs in approaches to and procedures for LHWO in two 4.5-hour sessions. Each LHW received a Vietnamese-language flip chart and booklet to explain breast cancer causes and screening by CBE and mammography and a training manual with answers to frequently asked questions.

Eligibility Criteria and Randomization

Researchers trained LHWs on how to recruit participants via lecture, role-play, and group discussions. Each LHW then recruited 22 women from their social networks. Eligibility criteria for participants included Vietnamese ethnicity, female gender, age ≥40 years, and residence in the county. LHWs contacted face-to-face or by telephone women in their social network (e.g., relatives, neighbors, coworkers, members of the same churches or temples) and asked them to participate in a research project promoting breast cancer screening. LHWs were taught not to coerce participants but could recruit them in Vietnamese or English. LHWs did not enroll participants but submitted names of those interested to the research team. Researchers randomized each LHW’s participants into the two groups (LHWO+ME or ME) using a random drawing of names in which the first name was assigned to one group, the second to the other, and so on. Occasionally, women were recruited from the same households and, because of the likelihood of contamination, received the same randomization assignment. After randomization, a researcher called each participant to enroll her and administered the baseline survey. All participants received a $30 incentive.

The LHWO+ME Group

The LHWs organized two small group outreach sessions lasting about 90 minutes for three to ten women at CBO offices or the LHW’s or a participant’s home. At the first session, LHWs gave a 15- to 20-minute presentation about breast cancer, CBE, and mammography and then led a question-and-answer session. LHWs used the flip chart and booklet as the basis for factual information and for motivation, but led the sessions using the approach they felt would be most effective.26 Some LHWs focused on fear-based messaging (e.g., stories about women diagnosed late who died, leaving their children behind) while others promoted benefits of screening (e.g., women diagnosed early requiring less intensive therapy). Within 1–2 months, the LHWs contacted participants to explain how to access screening and help with scheduling appointments. The second session occurred ~2 months later, when the LHW answered participants’ questions and re-emphasized the benefits of screening. One month later, LHWs called participants to follow up and remind them about the post-intervention survey.

The ME Group

Both the LHWO and the ME group were exposed to a background community-wide breast cancer ME campaign, which began concurrently with LHWO. The campaign focused on increasing awareness of breast cancer, addressing its cultural stigma, teaching its curability when detected early, shaping attitudes about screening tests, and encouraging women to obtain them. There were six Vietnamese-language TV and radio advertisements, 13 newspaper advertisements, and six newspaper articles. In the advertisements, Vietnamese doctors advised patients to obtain screening, Vietnamese women asked their doctors for screening, and Vietnamese breast cancer survivors provided testimonials. The campaign also publicized a navigator service and the availability of screening through the federally funded Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program. Each TV advertisement was shown on two channels with 34 spots monthly; each radio advertisement was broadcast on four stations with 112 spots monthly. Newspaper advertisements were printed in six newspapers or magazines with 72 printed ads monthly. The campaign created and distributed 45,000 bilingual breast cancer–screening booklets, 8500 silk roses with screening reminder cards, and 7500 reminder calendars. Research staff and community representatives (who were not LHWs) distributed these items directly to community members at flea markets, cultural events, and community forums, or to staff at physicians’ offices, CBOs, temples, pagodas, and churches for distribution over time.

After the post-intervention survey, ME group participants received a single group education session from their LHWs (delayed intervention).

Data Collection

By telephone, a researcher administered a pre-intervention survey to all participants 1 month before the first LHWO session and a post-intervention survey approximately 2 months after the second session. Survey items (yes–no and multiple-choice questions) were developed, pretested, and revised in Vietnamese and English.

Variables

Demographic measures included age, educational attainment, years in the U.S., marital status, health insurance status, English fluency, and family history of breast cancer. Breast cancer and screening knowledge were measured using ten items based on the information delivered in the LHW sessions and ME campaign. Participants were asked at what age women should start mammograms, CBEs, or breast self-examinations and if fatty diet, menopause, heredity, hormone replacement, breastfeeding, lack of physical activity, and God’s will were each a potential cause of breast cancer. Responses to each of the ten variables were re-coded as correct versus others (incorrect or missing). Responses were then combined into a knowledge scale ranging from 0 to 10 (with 10=most knowledgeable). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the knowledge scale was 0.66.

Four items were used to assess the amount of exposure to the ME campaign. The participants were asked if, in the past 6 months, they had seen or heard a Vietnamese-language TV, newspaper, or radio advertisement about breast cancer or seen or heard about a toll-free telephone number to obtain low-cost breast screening. Responses were combined into an exposure score ranging from 0 to 4 (with 4=exposed to all).

Outcome Variables

Outcome measures included ever having heard of breast cancer, having heard of a mammogram, ever having had a mammogram, having had a mammogram within the past 2 years, and planning on obtaining a mammogram within the next 12 months. Similar outcomes were collected for CBE.

Sample Size Calculations

Calculations were performed to determine the sample size needed to find an intervention effect on the primary outcome of having had a mammogram within the past 2 years. Based on a community-wide survey conducted in 2003, the baseline rate was estimated at 75% in both the LHWO+ME and ME-only groups. To detect a 15% intervention group effect size, a 5% comparison effect size, and a net effect size of 10% at post-intervention, the required sample size was 495 in each arm (α = 0.05 and β = 0.20).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted from 2007 to 2009 on data from all five CBOs combined. Descriptive statistics, including means, percentages, and 95% CIs, were computed for each independent and outcome variable by group assignment. Initial analyses used McNemar’s chi-square tests and Student’s paired t test to examine pairwise differences between pre- and post-intervention data within the two groups. Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact test, and Student’s t tests were used to explore differences between the groups at the pre- and post-intervention periods. A linear model was used for each of the items of interest to test for any differences in the change from pre- to post-intervention between the two groups.

The major hypotheses of intervention effects on post-intervention screening were assessed using logistic regression analysis for binary outcomes. Multivariate models (Model 1) were constructed for the outcomes of ever had a mammogram, had a mammogram in the past 2 years, ever had a CBE, and had a CBE in the past 2 years. In these models, control variables included LHWO agency/CBO, age, English-language proficiency, years in the U.S., education, employment, marital status, family history of breast cancer, and health insurance. Significant differences in baseline screening between the intervention and the comparison groups were accounted for by including baseline screening status as a covariate in Model 1. Adjustment was made for household clusters, because 54 of the 1031 households had two or three participants. To assess the effect of knowledge and media exposure, a second set of models (Model 2) was constructed, with changes in knowledge and media exposure added to the variables in Model 1. Max re-scaled R2 was used as a measure of goodness of fit. Data were analyzed with SAS version 9.1 and values were considered significant at p=0.05.

Results

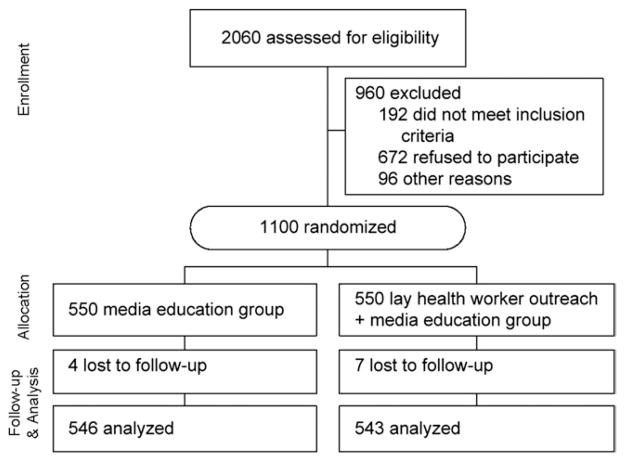

The 50 LHWs ranged in age from 22 to 67 (mean=48) years. They included housewives, students, and other members of the community. Each LHW recruited 22 participants into the study, yielding a total of 1100. All ME (n=550) and LHWO+ME (n=550) participants completed pre-intervention surveys; almost all (546 ME and 543 LHWO+ME) completed post-intervention surveys (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in measured sociodemographic characteristics between the two groups at baseline (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of Vietnamese-American women at baseline by intervention and comparison groups (% unless otherwise indicated)

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ME group (n=550) | LHWO+ME group (n=550) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 57.6 (10.5) | 57.0 (10.1) | 0.31 |

| Residence in U.S. (years), M (SD) | 14.0 (7.7) | 13.2 (7.8) | 0.09 |

| Self-rated English-speaking ability, poorly or not at all, (%) | 96.9 | 97.5 | 0.72 |

| Educational attainment <12 years | 59.8 | 56.6 | 0.30 |

| Marital status | 0.95 | ||

| Married | 70.6 | 70.9 | |

| Widowed | 14.6 | 13.5 | |

| Divorced or separated | 9.3 | 6.9 | |

| Never married | 5.5 | 8.7 | |

| Employment status | 0.61 | ||

| Currently employed | 32.0 | 33.6 | |

| Unemployed | 7.8 | 7.8 | |

| Homemaker | 58.4 | 55.1 | |

| Student | 0.9 | 1.3 | |

| Retired | 0.9 | 2.2 | |

| Health insurance status | 0.39 | ||

| None | 18.9 | 21.6 | |

| Public | 59.3 | 59.1 | |

| Private | 21.8 | 19.3 |

LHWO, lay health worker outreach; ME, media education

Knowledge About Breast Cancer

Table 2 shows the changes in knowledge in the ME and LHWO+ME groups from pre- to post-intervention. At pre-intervention, both groups had similar levels of knowledge for each of ten items and in the overall knowledge score (4.28 vs 4.34, p=0.63). At post-intervention, the ME group showed significantly increased knowledge in only one item, heredity as a cause of breast cancer. In the LHWO+ME group, there were significant increases in seven items, a significant decrease in one item, and no change in two items. Participants in the LHWO+ME group showed a net increase in knowledge score while those in the ME group showed a net decrease in knowledge score (+2.39 vs −2.32, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Knowledge regarding causesa of and screeningb for breast cancer by intervention group, at pre- and post-intervention

| Percentage correct

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ME group

|

LHWO+ME group

|

Intervention (LHWO+ME) minus comparison (ME)

|

|||||

| Pre | Post | Change | Pre | Post | Change | Change | |

| Fatty diet causes breast cancer (correct answer=yes) | 21.2 | 23.0 | 1.8 | 20.1 | 69.3 | 49.2* | 47.4* |

| Heredity causes breast cancer (yes) | 23.9 | 33.3 | 9.3* | 20.7 | 78.2 | 57.4* | 48.1* |

| Hormone replacement therapy causes breast cancer (yes) | 6.7 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 5.6 | 52.1 | 46.6* | 44.9* |

| Lack of physical activity causes breast cancer (yes) | 11.1 | 13.1 | 2.0 | 12.5 | 51.8 | 39.3* | 37.3* |

| Breastfeeding causes breast cancer (no) | 97.9 | 97.9 | 0.0 | 98.6 | 97.2 | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| Menopause causes breast cancer (no) | 93.9 | 92.0 | −1.9 | 92.8 | 84.1 | −8.7* | −6.8* |

| God’s will causes breast cancer (no) | 91.4 | 90.3 | −1.1 | 89.5 | 92.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 |

| Age at which women should start receiving regular mammograms is 40 years (yes) | 29.8 | 31.1 | 1.3 | 28.5 | 72.7 | 44.2* | 42.9* |

| Age at which women should start receiving regular CBEs is 40 years (yes) | 23.4 | 25.1 | 1.6 | 23.1 | 67.2 | 44.1* | 42.5* |

| Age at which women should start breast self-examinations is 20 years (yes) | 3.6 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 30.9 | 26.0* | 25.4* |

| Summary knowledge score,c M | 4.28 | 1.96 | −2.32* | 4.34 | 6.72 | 2.39* | 4.71* |

The denominator for knowledge items about the causes of breast cancer is women who had ever heard of breast cancer (n=487 in Media Education Comparison Group; n=541 in LHWO+ME intervention group at post-intervention).

The denominator for knowledge items about breast cancer screening is all women (n=546 in the ME comparison group; n=543 in the LHWO+ME intervention group at post-intervention).

A knowledge summary score was created using the ten items shown in this table. Further details are provided in the Methods section.

p<0.001

LHWO, lay health worker outreach; ME, media education

Breast Cancer–Screening Outcomes

Table 3 shows self-reported breast screening outcomes at pre- and post-intervention.

Table 3.

Breast cancer–screening outcomes by intervention and comparison groups

| ME group (n =546)

|

LHWO+ME group (n=543)

|

Intervention (LHWO+ME) minus comparison (ME)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Change | Pre | Post | Change | Change | |

| Ever heard of breast cancer | 86.6 | 89.1 | 2.5 | 88.5 | 99.6 | 11.1*** | 8.6** |

| Ever heard of a mammogram | 95.1 | 96.8 | 1.8 | 93.8 | 99.6 | 5.8*** | 4.0* |

| Ever had a mammogram | 89.6† | 91.8 | 2.2 | 84.1 | 91.6 | 7.5*** | 5.3* |

| Had a mammogram in the past 2 years (all participants) | 74.0† | 75.6 | 2.4 | 64.7 | 82.1 | 16.2*** | 14.2*** |

| Ever thought about getting a mammogram if never had one | 52.6 | 54.8 | 2.2 | 61.4 | 91.1 | 29.7*** | 27.5* |

| Plan a mammogram in the next 12 months | 73.7 | 75.3 | 1.6 | 72.8 | 95.7 | 22.9*** | 21.3*** |

| Ever heard of a CBE | 76.4 | 86.1 | 9.7*** | 77.5 | 99.4 | 21.9*** | 12.2*** |

| Ever had a CBE | 73.1 | 79.0 | 5.9*** | 68.1 | 85.5 | 17.1*** | 11.2** |

| Had a CBE in past 2 years (all participants) | 54.7† | 59.0 | 4.2* | 48.7 | 71.6 | 23.1*** | 18.9*** |

| Ever thought about getting a CBE if never had one | 44.4 | 50.0 | 5.6 | 44.6 | 61.8 | 17.2* | 11.6 |

| Plan a CBE in the next 12 months | 72.3 | 71.7 | −0.6 | 68.4 | 89.7 | 21.3*** | 21.9*** |

p<0.05 (for difference in pre-intervention rates between intervention and comparison groups),

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

CBE, clinical breast examination; LHWO, lay health worker outreach; ME, media education

Awareness of breast cancer was high at pre-intervention. At post-intervention, the LHWO+ME group significantly increased awareness (88.5% to 99.6%, p<0.001) while the ME group did not (86.6% to 89.1%, p=0.18), with the change in the LHWO+ME group being greater than that in the ME group (11.1% vs 2.5%, p<0.01).

Mammography outcomes

The LHWO+ME group had a larger increase in awareness of mammography than the ME group (5.8% vs 1.8%, p<0.05). For mammogram receipt, the LHWO+ME group had a lower baseline rate than the ME group for ever having had a mammogram (84.1% vs 89.6%, p<0.05) and having had one within the past 2 years (64.7% vs 74.0%, p<0.05). At post-intervention, the ME group had a nonsignificant increase in ever having a mammogram (89.6% to 91.8%, p=0.05) while the LHWO+ME group had a significant increase (84.1% to 91.6%, p<0.001). The intervention effect size was significantly greater than the comparison effect size (7.5% vs 2.2%, p<0.001). For mammogram within the past 2 years, the ME group had a nonsignificant increase (74.0% to 75.6%, p=0.37), but the LHWO+ME group had a significant increase (64.7% to 82.1%, p<0.001). The intervention effect size was significantly greater than the comparison effect size (16.2% vs 2.4%, p<0.001). Similar findings were found for ever having thought about obtaining a mammogram and for planning to obtain a mammogram in the next 12 months.

Clinical breast examination outcomes

Awareness of CBE increased significantly in both the ME group (76.4% to 86.1%, p<0.001) and the LHWO+ME group (77.5% to 99.4%, p<0.001). Both groups had a similar baseline rate for ever having had CBE, but the LHWO+ME group had a lower rate for having had CBE in the past 2 years (48.7% vs 54.7%, p<0.05). The rate for ever having had CBE increased in both the ME (73.1% to 79.0%, p<0.001) and LHWO+ME groups (68.1% to 85.5%, p<0.001), with the LHWO+ME group having a significantly greater increase (17.1% vs 5.9%, p<0.01). Similarly, receipt of a CBE within the past 2 years increased in both the ME group (54.7% to 59.0%, p<0.05) and the LHWO+ME group (48.7% to 71.6%, p<0.001), with the LHWO+ME group having a significantly greater increase (23.1% vs 4.2%, p<0.001). At post-intervention, the LHWO+ME group were also more likely than the ME group to have thought about obtaining a CBE and to be planning to obtain a CBE in the next 12 months.

Table 4 shows the multivariate results for mammography screening outcomes. In Model 1, after controlling for LHW agency, baseline mammogram receipt status, age, English proficiency, years in the U.S., education, employment, marital status, family history of breast cancer, household clusters, and health insurance, the OR for ever having had a mammogram was 3.62 (95% CI = 1.35, 9.76) in the LHWO+ME compared to the ME group. In Model 2, which added knowledge scale and media exposure score to Model 1, the OR for ever having had mammography in the LHWO+ME versus ME group was 4.13 (95% CI=1.36, 12.56). For mammography within the past 2 years, the OR was 3.14 (95% CI=1.98, 5.01) for the LHWO+ME versus ME group in Model 1 and 3.21 (95% CI=1.92, 5.36) in Model 2.

Table 4.

Multivariate models for mammography outcomes

| Model 1,a OR (95% CI)

|

Model 2,b OR (95% CI)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever had a mammogram | Mammogram in the past 2 years | Ever had a mammogram | Mammogram in the past 2 years | |

| Intervention (ref=ME) | ||||

| LHWO+ME | 3.62 (1.35, 9.76) | 3.14 (1.98, 5.01) | 4.13 (1.36, 12.56) | 3.21 (1.92, 5.36) |

| Age (ref=50–64 years) | ||||

| 40–49 years | 0.85 (0.26, 2.76) | 0.51 (0.30, 0.87) | 0.86 (0.25, 2.89) | 0.56 (0.32, 0.98) |

| ≥ 65 years | 1.31 (0.31, 5.47) | 0.46 (0.25, 0.86) | 1.64 (0.36, 7.60) | 0.52 (0.27, 1.01) |

| Health insurance (ref=no) | ||||

| Yes | 2.90 (0.99, 8.20) | 2.84 (1.73, 4.69) | 2.88 (0.93, 8.93) | 2.49 (1.48, 4.18) |

| Knowledge score (each point) | — | — | 0.86 (0.71, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.10) |

| Media exposure score (each point) | — | — | 1.15 (0.78, 1.70) | 0.92 (0.77, 1.10) |

Note: Max re-scaled R2s are as follows: Model 1, receipt ever=0.75; Model 1, receipt within 2 years=0.44; Model 2, receipt ever=0.76; Model 2, receipt within 2 years=0.45.

Model 1 adjusted for baseline screening status, lay health worker agency, language proficiency, years in the U.S., education, employment, marital status, family history of breast cancer, and household clusters

Model 2 adjusted for all covariates in Model 1, plus changes in knowledge and media exposure scores

LHWO, lay health worker outreach; ME, media education

Table 5 shows the multivariate results for CBE outcomes. The LHWO+ME intervention OR for ever having had a CBE was 2.94 (95% CI=1.63, 5.30) and for having had a CBE within the past 2 years was 3.04 (95% CI=2.11, 4.37) in Model 1. When knowledge scale and media exposure score were added in Model 2, the intervention ORs remained significant for ever having had CBE (OR 2.63; 95% CI = 1.34, 5.16) and had a CBE in the past 2 years (OR 2.67; 95% CI = 1.78, 4.02).

Table 5.

Multivariate models for CBE outcomes

| Model 1,a OR (95% CI)

|

Model 2,b OR (95% CI)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever had a CBE | CBE in the past 2 years | Ever had a CBE | CBE in the past 2 years | |

| Intervention (ref=ME) | ||||

| LHWO+ME | 2.94 (1.63, 5.30) | 3.04 (2.11, 4.37) | 2.63 (1.34, 5.16) | 2.67 (1.78, 4.02) |

| Age (ref=50–64 years) | ||||

| 40–49 years | 0.99 (0.45, 2.15) | 0.70 (0.45, 1.08) | 1.07 (0.47, 2.45) | 0.73 (0.46, 1.15) |

| ≥ 65 years | 1.08 (0.52, 2.26) | 0.51 (0.31, 0.83) | 1.21 (0.57, 2.57) | 0.56 (0.34, 0.93) |

| Health insurance (ref=no) | ||||

| Yes | 0.89 (0.41, 1.92) | 1.31 (0.87, 2.00) | 0.84 (0.36, 1.97) | 1.25 (0.80, 1.92) |

| Knowledge score (each point) | — | — | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) |

| Media exposure score (each point) | — | — | 1.12 (0.87, 1.43) | 1.05 (0.90, 1.21) |

Note: Max re-scaled R2s are as follows: Model 1, receipt ever=0.61; Model 1, receipt within 2 years=0.36; Model 2, receipt ever=0.61; Model 2, receipt within 2 years=0.36.

Model 1 adjusted for baseline screening status, lay health worker agency, language proficiency, years in the U.S., education, employment, marital status, insurance, family history of breast cancer, and household clusters

Model 2 adjusted for all covariates in Model 1, plus changes in knowledge and media exposure scores

CBE, clinical breast examination; LHWO, lay health worker outreach; ME, media education

Discussion

In this RCT of LHWO delivered against a background of a media campaign among Vietnamese American women aged ≥40 years, the LHWO+ME intervention was significantly more effective than ME alone in improving knowledge of breast cancer, receipt ever of mammography and CBE, receipt within the past 2 years of mammography and CBE, and intention to obtain mammography and CBE within the next 12 months. The ethnic media campaign did not increase knowledge of breast cancer or receipt of mammography in the comparison ME cohort, although receipt ever of CBE and receipt of CBE within the past 2 years did have small and significant increases. The multivariate analyses showed that the LHWO+ME was more effective than the ME intervention for ever having had and recent receipt of mammograms and CBEs, with ORs in the 2–3 range.

Intervention effect sizes were about 7% and 17% for ever having had, and 16% and 23% for having had within the past 2 years, mammography and CBE, respectively. In comparison, Sung et al.27 found that LHWO increased mammography receipt by 10%–12% among African American women and Navarro et al.15 reported an increase in mammography receipt within the past year of 21% among Latina women, although neither study found a significant effect for CBE. Taken together, these findings support the idea that LHWO is an effective tool to promote breast cancer screening among ethnic-minority women.

One question was whether LHWO was more effective among women who have never had a screening test, who are often thought to be the most difficult to reach, or among women who have had screening. The LHWO effect size on receipt ever was variable, with 7.5% for mammogram and 17.1% for CBE, while the effect size on recent receipt was 16.2% and 23.1%, respectively. The intervention OR for ever and recent receipt for each test was similar. The small effect size for receipt ever of mammogram may be due to a ceiling effect, because in this study more than 84% had ever had a mammogram at baseline. These findings suggest, but do not establish conclusively, that LHWO is effective for receipt ever and recent receipt of CBE and possibly for mammograms.

The underlying mechanisms through which LHWs promote healthy behaviors remain poorly defined.28 It has been stated that LHWs provide emotional, instrumental, informative, and appraisal support.12,14,28–30 In this study, LHWO was very effective in the informative function by increasing knowledge about breast cancer and screening recommendations. However, the effectiveness of LHWO on screening receipt was not mediated by knowledge change, because knowledge change was not independently associated with test receipt and the effect on the intervention ORs when knowledge was added to the model (Model 2) was mixed. This is similar to the findings from a previous cervical-screening LHWO study.25 It is possible that LHWO is effective because the LHWs share a common cultural background and a social relationship with group participants, have frequent contacts with the participants, and serve as behavioral role models, but these possibilities remain questions for future studies. In particular, the role of social networks on the effectiveness of LHWO is a promising area for further research.

Because this LHWO study is the second one that this group conducted with the same LHWO agencies, many of the problems encountered in the prior study were minimized. The process was more efficient, as shown by the fact that the same number of agencies, LHWs, and participants completed the study in 3 instead of 4 years. Participant recruitment, retention, and satisfaction with the research process were better. Issues specifically related to research, such as the process of randomization, which caused substantial problems in the cervical cancer study, were minimal. These experiences show one often-underestimated advantage of the LHWO approach—once the process has been implemented for one health concern, it is much easier to adapt it to a new health issue.

A finding from this study and other published literature is that media campaigns, even when they are targeted and tailored, have a limited effect on cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. In a prior 24-month media campaign to promote breast and cervical cancer screening, the campaign was effective in increasing awareness of breast cancer–screening tests but not in increasing receipt ever or recent receipt of either test.22 In the current study, the ME group did not have significant increases in awareness or receipt of mammography, although there were significant, but modest, increases in awareness and receipt of CBE. This may be due to the fact that getting a CBE is a one-step process (seeing a doctor) while receipt of mammography is a two-step process (seeing a doctor and then getting a mammogram), or due to the lower baseline rates of CBE compared with mammography outcomes.

This study has some limitations. There was no group that received either LHWO alone or neither LHWO nor ME. Thus, the results do not show conclusively that LHWO alone is effective, because there may be a synergistic effect between the LHWO and the ME campaign. However, the findings from the present breast screening study and a prior cervical screening study25 indicate that LHWO is more effective than ME in increasing knowledge and screening behavior among Vietnamese American women. Another limitation of this study is its reliance on self-reports of receipt of breast screening. There are no published studies validating Vietnamese American women’s self-reports of breast screening; the validation rate for self-reports of mammography was only 66.7% among Chinese American women compared to 89.3% among non-Hispanic white women in a prior study published by this group.31 Women in the LHWO+ME group may have understood better than those in the ME-only group that they were supposed to obtain breast cancer screening and therefore have given the socially desirable answer during post-intervention surveys. A third limitation is that there was no blinding, either of the participants or the surveyors, to the randomization assignment. There was no “placebo control” for the number of educational sessions for the comparison group (i.e., they did not attend two educational sessions on some other topic). In addition, as a result of balancing community inputs about the burdens of research participation with research needs, there was a limited number of predictors measured by the surveys. Finally, the baseline screening participation was lower in the LHWO+ME group than in the ME group, although the multivariate models showing the effectiveness of the intervention adjusted for baseline screening.

Nevertheless, the study did have strengths compared with prior LHWO studies, including the randomized controlled design and the very high participant retention rates; thus, this study adds to the growing literature demonstrating that LHWO is an effective tool to address cancer-screening disparities in ethnic-minority women. LHWO offers a direct approach to promote cancer screening by focusing on those who are most under-served. Future research should focus on understanding how LHWO works, which activities and styles are effective, whether LHWO can work with men, and whether LHWO can be disseminated from Vietnamese-Americans to other ethnic groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the CDC under Cooperative Agreement U50/CCU922156. The Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research and Training, also supported this research through National Cancer Institute Cooperative Agreement U01/CA114640.

The authors acknowledge the substantial contributions and guidance of the Vietnamese Reach for Health Coalition, current Coalition Chair Tuyet Ha-Iaconis and immediate past Chair MyLinh Pham, and the Coalition’s 20 member organizations and community representatives. This project would also not have been possible without the extensive involvement and dedication of the five LHW agencies (Asian Americans for Community Involvement, Catholic Charities, Immigrant Resettlement & Cultural Center, Southeast Asian Community Center, and Vietnamese Voluntary Foundation, all located in Santa Clara County CA), their LHW coordinators, and the 50 participating LHWs.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC or the National Cancer Institute.

References

- 1.Reeves TJ, Bennett CE. The Asian and Pacific Islander population in the United States. Washington DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2003. Curr Popul Rep Popul Charact P20–540. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. The American Community Survey reports. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2007. The American community—Asians: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPhee S, Jenkins C, Hung S, et al. Behavioral risk factor survey of Vietnamese—California, 1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(5):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPhee SJ. Caring for a 70-year-old Vietnamese woman. JAMA. 2002;287(4):495–504. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Gildengorin G, et al. Papanicolaou testing among Vietnamese Americans: results of a multifaceted intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller BA, Chu KC, Hankey BF, Ries LA. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns among specific Asian and Pacific Islander populations in the U.S. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(3):227–56. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keegan TH, Gomez SL, Clarke CA, Chan JK, Glaser SL. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence among 6 Asian groups in the Greater Bay Area of Northern California. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(6):1324–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez S, Le G, Miller T, et al. Cancer incidence among Asians in the Greater Bay Area, 1990–2002. Fremont CA: Northern California Cancer Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez SL, Tan S, Keegan TH, Clarke CA. Disparities in mammographic screening for Asian women in California: a cross-sectional analysis to identify meaningful groups for targeted intervention. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kandula NR, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS. Low rates of colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in Asian Americans compared with non-Hispanic whites: cultural influences or access to care? Cancer. 2006;107(1):184–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownstein JN, Cheal N, Ackermann SP, Bassford TL, Campos-Outcalt D. Breast and cervical cancer screening in minority populations: a model for using lay health educators. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7(4):321–6. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corkery E, Palmer C, Foley ME, Schechter CB, Frisher L, Roman SH. Effect of a bicultural community health worker on completion of diabetes education in a Hispanic population. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(3):254–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Becker AB, Hollis RM. It’s a 24-hour thing … a living-for-each-other concept”: identity, networks, and community in an urban village health worker project. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(4):465–80. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro AM, Senn KL, McNicholas LJ, Kaplan RM, Roppe B, Campo MC. Por La Vida model intervention enhances use of cancer screening tests among Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(1):32–41. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn MT, McNabb WL. Training lay health educators to conduct a church-based weight-loss program for African American women. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27(2):231–8. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Community health workers: working document for the WHO Study Group. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewin SA, Dick J, Pond P, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Heath J. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(4):358–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos: a qualitative systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):418–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins CN, McPhee SJ, Bird JA, et al. Effect of a media-led education campaign on breast and cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese-American women. Prev Med. 1999;28(4):395–406. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Bui-Tong N, et al. Community-based participatory research increases cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese-Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(2S):31–54. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam TK, McPhee SJ, Mock J, et al. Encouraging Vietnamese-American women to obtain Pap tests through lay health worker outreach and media education. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(7):516–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mock J, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, et al. Effective lay health worker outreach and media-based education for promoting cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese American women. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1693–1700. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mock J, Nguyen T, Nguyen KH, Bui-Tong N, McPhee SJ. Processes and capacity-building benefits of lay health worker outreach focused on preventing cervical cancer among Vietnamese. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3S):223S–232S. doi: 10.1177/1524839906288695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung JF, Blumenthal DS, Coates RJ, Williams JE, Alema-Mensah E, Liff JM. Effect of a cancer screening intervention conducted by lay health workers among inner-city women. Am J Prev Med. 1997;13(1):51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasick RJ, Hiatt RA, Paskett ED. Lessons learned from community-based cancer screening intervention research. Cancer. 2004;101(5S):1146–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Israel BA. Social networks and social support: implications for natural helper and community level interventions. Health Educ Q. 1985;12(1):65–80. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eng E, Smith J. Natural helping functions of lay health advisors in breast cancer education. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35(1):23–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00694741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McPhee SJ, Nguyen TT, Shema SJ, et al. Validation of recall of breast and cervical cancer screening by women in an ethnically diverse population. Prev Med. 2002;35(5):463–73. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.