Abstract

In man, as in mouse, diversification of the antibody repertoire appears to follow a strict developmental program whereby antigen specificities are serially acquired during ontogeny. When compared to the adult repertoire, the fetal antibody repertoire is highly enriched for polyreactive specificities of low affinity. Although the mechanisms governing the development of this fetal repertoire differ between human and mouse, the composition and structure of the fetal antibodies produced by both species are quite homologous. Specifically, both species use similar V gene segments and restrict the sequence and structure of the third complementarity determining region (HCDR3) of the antibody heavy chain. The precise role that this restriction of the HCDR3 might play in the development of immunocompetence in the human remains to be elucidated.

Keywords: antibody repertoire, development, ontogeny

It has long been clinically apparent that restriction in the immune response of the infant correlates with an increased risk of infection1,2. Acquisition of antigen responsiveness proceeds in parallel with a regulated diversification of the antibody repertoire (reviews3–5). It is uncertain, however, whether regulation of repertoire diversity in the B cell and limitations in the range of antigen specificities reflects a true cause-and-effect relationship. Fundamentally, it remains unresolved why the composition of the B cell receptor repertoire is developmentally controlled.

Antibody molecules, or immunoglobulins, are heterodimeric proteins composed of two heavy (H) and two light (L) chains each composed of a constant (C) domain that defines effector function and a variable (V) domain that determines antigen specificity (reviews6,7). The V domain is the product of a series of gene rearrangement events6,8–12. The L chain V domain is created by joining a variable (VL) to a joining (JL) gene segment. The H chain V domain contains an additional diversity (DH) gene segment between VH and JH. V domains include four intervals of relatively constant sequence (termed frameworks or FRs) that are separated from each other by three hypervariable intervals (termed complementarity determining regions or CDRs). CDRs 1 and 2, which form the outside borders of the antigen binding site, are encoded entirely by the V gene segments. The CDR3 intervals are the direct product of V(D)J joining and lie at the center of the antigen binding site.

N region addition and use of a DH gene segment to the H chain greatly enhances the potential for diversity in the HCDR3 interval. First, DH gene segments, which can rearrange by either inversion or deletion, effectively encode six different peptide fragments each. Second, D–D joining is allowed. Third, one or two nucleotides palindromic (P junctions) to the termini of the gene segment can be added during rearrangement13. Finally, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) can catalyze the addition of non-germline encoded nucleotides (N regions) between the V, D and J gene segments14, increasing the potential diversity of the repertoire by a factor of twenty for each added codon.

Typically, immunoglobulin assembly begins in the H chain locus15 with DH → JH joining followed by VH → DJ rearrangement. The nascent μ chain must then form a successful complex with ψLC components16,17. Subsequent production of a κ or λ L chain enables surface expression of IgM and allows antigen selection of the immature B lymphocyte. Exposure to antigen at this stage can result in further L chain rearrangement18,19, anergy, or even cell death. In this way, B cells expressing deleterious antibodies can be modulated.

The ability to respond to specific antigens is restricted at the earliest stages of life, and is subsequently acquired in a controlled, stepwise fashion1–3,20. The programmed acquisition of antigen specificities appears to be a fundamental property of the developing immune system, with multiple species following similar, albeit not identical, patterns3,21–24. These restrictions seem paradoxical, given the otherwise stochastic mechanisms that appear to underlie the generation of the antibody repertoire. The observation that the range of diversity exhibited by the repertoire of antigen binding sites is also regulated during ontogeny has helped resolve this apparent paradox (reviews4,5). However, the question of whether these restrictions in the antibody repertoire represent the cause or the effect of an inability to respond to antigen remains unanswered.

The development of the antibody repertoire has been best studied in the mouse. Pre-B cells and surface IgM positive B cells (sIgM+) appear in the fetal liver at gestational days 12 and 16–17, respectively25. V utilization is non-random, with more than 80% of these cells utilizing members of the VH7183 family26–30. In contrast, the VHJ558 family contributes little to the fetal repertoire but is represented in more than half of splenic B cells only a week after birth29,31,32.

It is unclear whether genetic regulation of gene utilization or antigen receptor-influenced selection plays the greater role in the development of the early repertoire. The VH7183 gene segment family is nearest to the JH locus, with VH81X, the most frequently used gene segment, being the most proximal26,27. This suggests that proximity to the J–C enhancer region influences rearrangement frequency. Changes in VH gene segment representation could thus be the product of selection by antigen of the less common B cells that have rearranged alternative VH gene segments. Such selection would appear to first become manifest in the bone marrow, because emerging B cells already have a diminished frequency of VH7183-containing cells33. Exposure to the environment also appears to play a role, because germ-free mice continue to express the VH 7183 family at more than double the rate seen in normal mice29,34.

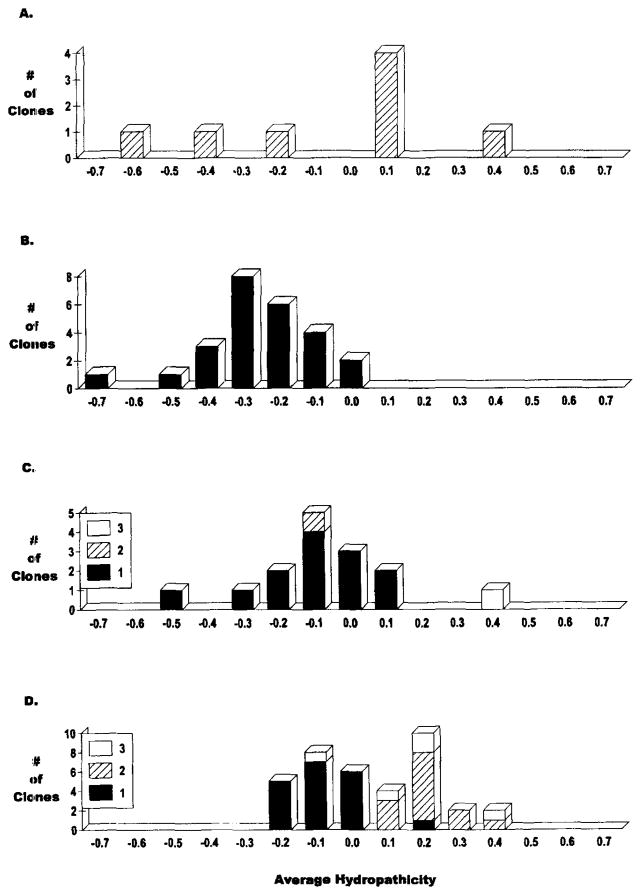

Support for the alternative hypothesis, that the ontogeny of the diversity of the repertoire is regulated at the genetic level, derives from analysis of HCDR3. Fetal B cell progenitors lack TdT, limiting HCDR3 diversity to germline encoded sequence35,36. This restriction probably contributes to the similarity in idiotypes expressed by antibodies derived from the perinatal repertoire37. Lack of N region addition also has a dramatic effect on the hydropathicity of the antigen binding site (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A comparison of the average hydropathicity of HCDR3 intervals in the mouse: (A) fetal non-productive VDJ joins from liver; (B) fetal productive VDJ joins from liver; (C) adult productive VDJ joins from spleen; (D) adult productive VDJ joins from λ5/λ6 ‘knock out’ mice. For (C) and (D), the identity of the reading frame by deletion is noted (RF1, 2 or 3). (Sequence analysis was performed on sequences from Feeney and Löffert et al10).

Although each DH gene segment has six potential reading frames (RFs), there is a striking preference for use of only one — RF135,36,38. The mechanisms that underlie this preference have been well worked out. First, DH rearrangement preferentially involves deletion over inversion, limiting use of the three reading frames generated by inversion (i-RFs). Second, germline encoded stop codons at the center of RF3 lead to premature termination of translation, limiting use of RF3. Third, there is a conserved ATG translation start site upstream in RF2. DH transcripts that use RF2 can be translated to form a Dμ protein that may trigger allelic exclusion, preventing further V→DJ rearrangement39. This process is dependent on surface expression of μ–ψLC, because RF2 is used in mice where the λ5 gene has been ‘knocked out’40. This preference for RF1 influences the hydropathicity of CDR341. In the Kyte–Doolittle hydropathicity index42, the most highly charged residue (Arginine) is assigned a value of −1.3, neutral Glycine has an assigned value of 0.03, and the most hydrophobic residue (Isoleucine) has a value of 1.7. There is a marked consistency in the hydropathicity of each reading frame in mouse DH. The preferred reading frame by deletion, RF1, has an average hydropathicity index of −0.34 ± 0.11. This reading frame is also characterized by the presence of a Glycine residue in the middle of the D — the location most likely to be preserved during splicing — and by the frequent presence of Tyrosine residues. The Dμ protein reading frame, RF2, is relatively hydrophobic (index 0.58 ± 0.23), as is the reading frame with the embedded termination codon, RF3 (index 0.82 ± 0.22). In rearrangements that undergo DH inversion, RF1 is highly charged (index −0.73 ± 0.17), RF2 is hydrophobic (index 1.27 ± 0.16), and RF3 is neutral (index 0.24 ± 0.39) but includes a termination codon.

We turned to the literature for fetal and adult H chain sequences36,40 and analyzed the hydropathicity of the HCDR3 intervals from both productive (virtually all RF1) and non-productive (virtually all RF2) rearrangements (Figure 1). In the fetus, the average hydropathicity was similar to the germline RF1 DH sequence, i.e. slightly hydrophilic and enriched for glycine, tyrosine, and serine. With N region addition, the average HCDR3 hydropathicity becomes more neutral. It should be noted that hydrophobic HCDR3 sequences are not necessarily incompatible with forming IgM protein43. For example, use of RF2 is allowed in λ5/λ5 ‘knock out’ mice, and 50% of the sequences are in the hydrophobic range. The consequences of limiting hydropathicity are unclear, but it seems likely that this prejudice contributes to the self-reactivity, multi-reactivity, and low affinity exhibited by neonatal antibodies44–46.

One test of the significance of these restrictions is to determine if similar restrictions apply in another species, i.e. human. In human, pre-B cells can first be detected at 8 weeks gestation in the fetal liver, followed by identification of B cells at 9 weeks gestation. Plasma cells can be detected by 16 weeks gestation12,47. Late in the second trimester, production of B lineage cells shifts to the bone marrow where it remains throughout adult life.

Studies of H chain diversity in second trimester human fetal liver indicated that VH gene segment utilization was restricted to a small number of sequences4,48,49. As in the mouse, the most JH proximal VH gene segment, V6-1, was over-represented and sequences that used this gene segment were often self-reactive50. However, unlike the mouse, the most frequently utilized VH gene segments proved to be located one-third of the way up the V domain locus. Moreover, these gene segments continue to be used at high frequency in the adult, suggesting that J–C enhancer proximity does not play the most critical role in restricting the repertoire. There is an alternative explanation: fetal antibody sequences encode essential specificities.

Support for the view that the fetal repertoire is designed to express essential specificities comes from the strong conservation of sequence between some human and mouse ‘fetal’ VH gene segments51. For example, the human V3–23 and mouse VH283 (E415) gene segments are preferentially used in fetal life26,52. These gene segments share > 80% identity at the peptide level51. Both differ by no more than three base pairs from their respective family consensus sequences, thus they are prototypes for their families. Thus, the mouse and human fetal repertoires are enriched for prototypic, phylogenetically conserved V gene segments that appear capable of generating a plastic, polyreactive antibody repertoire53.

Intriguingly, these ‘fetal’ VH gene segments are also used in antibodies of specificities not found early in life, e.g. anti-polysaccharide responses52,54. Both can also encode pathogenic, self-reactive anti-DNA antibodies41,55–57. What then distinguishes fetal from adult H chain sequences, or fetal ‘natural’ autoantibodies from adult ‘pathogenic’ autoantibodies? One possibility is that control of HCDR3 plays a role. For example, one characteristic feature of anti-DNA antibodies is the presence of charged amino acids (e.g. arginine) in HCDR3. These arginines result either from N region addition or from use of alternative DH reading frames, e.g. use of RF3 orinvertedRF1 (reviewed in 58). Thus, fetal control of HCDR3 diversity could be a means to reduce the likelihood of generating pathogenic antibodies.

Analysis of the composition of HCDR3 fetal and neonatal sequences indicates that this interval is also a major focus of regulation in humans. Human DH gene segments can be grouped into eight different families (DXP, DLR, DA, DN, DM, DK, DIR, and DQ52)59,60. DHQ52 is located immediately adjacent to JHI. The other DH gene segments are located on four ~9 kb repeating structures, each of which contains at least one representative of each of the remaining seven families. We analyzed a representative sample of first and second trimester fetal liver μ transcripts in comparison to those in cord blood (Figure 2). We found a preference for DHQ52 in the fetus when compared to the neonate. In contrast, DHDXP and DLR containing transcripts were frequent in cord blood, but rare in fetal liver. Differences were also apparent in JH utilization, with JH6 common only in the neonate.

Figure 2.

Depicted is DH and JH and the distribution of H chain CDR3 lengths as found in 13 Cμ+ VDJ transcripts from five fetal liver samples ranging in age from 54 to 76 days gestation, 32 Cμ+ VDJ transcripts from 104 and 130 day fetal liver, and 14 cord mononuclear cell VDJ Cμ+ transcripts from one sample of cord blood mononuclear cells. On the left are the percentage of transcripts that utilize members of the designated DH families and on the right are the percentage of transcripts that utilize the designated JH gene segment. In the middle is the distribution of the lengths of the CDR3 intervals of these transcripts (residues 93–102) divided into three residue intervals (e.g. <9, 10–12, 13–15, 16–18, 19–21, 22–24, and >25 codons).

In order to determine if these differences in gene segment utilization were the result of antigen selection, we looked for the expression of the intermediate products of H chain rearrangement — DJ transcripts — in early B lineage cells from the fetus and the adult. These transcripts do not form functional antibody and thus cannot be selected by antigen. Fetal and adult bone marrow cells were sorted on the basis of the surface expression of CD34 and CD1961. The CD34+CD19− population contains a heterogeneous mixture of lymphoid progenitor cells, some of which may be committed to the B lineage62. The CD34+CD19+ population is comprised primarily of pro-B cells. Transcription of unrearranged DHQ52 gene segments was detected in both fetal and adult CD34+CD19− cells. In the fetus, rearranged DHQ52 transcripts were detected in both CD34+CD19− and CD34+CD19+ cells, but in the adult DHQ52 DJ rearranged transcripts were detected only in the CD34+CD19+ population. In contrast, a low level of DXP DJ transcripts was detected in the CD34+CD19− subpopulation in both fetus and adult, and abundant transcripts were detected in subpopulation 2 regardless of gestational age. With regards to JH utilization, we found that DHQ52 and DXP gene segments rearranged to different JH segments in the fetal CD34+CD19− cells. DHQ52 rearranged with JH2, JH3, and JH4 while DXP appeared to be restricted to JH4 and JH6 rearrangements. Thus, the pattern of DHQ52 transcription and JH utilization in early B cell subpopulations mirrored its expression in mature VDJ rearrangements, indicating that the differential use of these gene segments in H chain transcripts is under genetic control and cannot be attributed solely to selection by antigen.

In order to determine which of the four major mechanisms that serve to influence DH reading frame in the mouse were operating in man, we examined more than 100 DJ and VDJ sequences from 19 week fetal bone marrow pre-B and B cells (Figure 3). In both mouse and man, we found that deletion is favored over inversion, prejudicing DH reading frame to one of the three reading frames by deletion (Mechanism 1). Virtually all human DH gene segments lack the conserved upstream ATG start site seen in mouse and cannot generate uniform Dμ proteins, thus this mechanism is inoperative (Mechanism 2). The majority of human DH gene segments have a termination codon in the middle of DH; thus in human as in mouse, there is a reading frame that can be selected against on the basis of translatability (Mechanism 3). We next sought evidence of preferential splicing at sites of homology between the rearranging gene segments (Mechanism 4). In sequences which lacked N nucleotides, no effect on choice of reading frame was found.

Figure 3.

DH reading frame utilization as a function of B cell development in man. DH reading frame was assigned as Term (termination codon), Non-neutral (average polarity < −0.5 or > 0.5, see proposal for details), and Neutral (average polarity <0.5 and > −0.5). Shown is the DH reading frame for 47 DJ transcripts (DHQ52 and DHDXP, 22 VDJ transcripts from pre-B, and 39 VDJ transcripts from B cells where DH identity could be established. Polarities were calculated using the Kyte-Doolittle hydropathicity index.

Although human DH gene segments lack the ATG start site that defines mouse RF2, human DH gene segments follow the same charge pattern seen in mouse and thus RF can be assigned by charge distribution. As in the mouse, when rearranged by deletion, each DH exhibits a slightly hydrophilic RF (enriched for glycine, tyrosine and serine), a non-neutral RF (either hydrophobic or strongly charged), and an RF with an embedded termination codon; and in the inverted orientation, the neutral RF contains an embedded termination codon. In order to determine if there is an RF preference in human similar to mouse, we can group DH reading frames by their charge distribution, i.e. neutral, non-neutral and termination codon-containing. In 19-week fetal bone marrow, all three reading frames formed by deletion were used in DQ52 and DXP family DJ transcripts. Use of the reading frame with a termination codon decreased in pre-B VDJ and B cell VDJ CDR3 domains (p = 0.04). However, the neutral and non-neutral reading frames were used with equivalent frequency in both pre-B and B cell VDJ joins. Thus, by reading frame, human more closely approximates the pattern seen in λ5/λ5 ‘knock out’ mice, with use of both the neutral and non-neutral reading frame.

At first glance, these observations would suggest that a prejudice for the generation of slightly hydrophilic CDR3 domains might not be present in human. However, unlike the mouse, human fetal CDR3 domains contain extensive N region addition as well as DH gene segments that can undergo extensive exonucleolytic nibbling. Although both neutral and non-neutral DH reading frames were used in these fetal H chain variable domains, it was possible that exonucleolytic nibbling and N region addition could have adjusted the polarity of the CDR3 domain into the neutral range. Shown in Figure 4 is an analysis of the average polarity per amino acid of the HCDR3 in DJ and VDJ transcripts from 19 week fetal liver. In the DJ transcripts, 13% of the CDR3 intervals (six of 47) had an average polarity either > 0.5 or < −0.5. In contrast, none of the pre-B cell VDJ CDR3s and <2% of the B cell VDJ CDR3s had an average polarity outside this range (p = 0.02, χ2). These findings strongly support the hypothesis that maintenance of a slightly hydrophilic HCDR3 interval is a fundamental property of the developing repertoire. What these studies do not yet answer is whether the repertoire in the first trimester is further restricted with regards to hydropathicity.

Figure 4.

Polarity per amino acid of human H chain CDR3s. DJ and VDJ transcripts from pre-B and B cells from second trimester fetal liver have been analyzed. The hydropathicity of each amino within the CDR3 domain of the transcript was determined and the average hydropathicity per amino acid calculated. Shown in panel A is the average hydropathicity of the CDR3 domain of 47 DJ transcripts from pre-B cells. Panel B illustrates the average polarity of the CDR3 domain of 22 VDJ transcripts from the same pre-B cell fraction. Shown in panel C is the average polarity of the CDR3 domain of 64 VDJ transcripts from the B cell fraction.

In addition to sequence composition and reading frame, another major difference between fetal and neonatal HCDR3 intervals was length (Figure 2). The fetal HCDR3 intervals averaged 11–12 codons and were all less than 18 codons long, whereas cord blood HCDR3 intervals averaged 17–18 codons and ranged between 6 and 24 codons in length. A similar range of lengths is characteristic of the adult repertoire in the blood63. Thus, entire ranges of HCDR3 structures present in the neonate and adult appeared to be rare, or absent, in the fetus.

These data were re-evaluated in order to determine if differences in DH and JH gene segment utilization or in N region addition could explain the differences in CDR3 length distribution. Including potential P junctions, DHDXP and DLR gene segments can encode up to 11 and 2/3 codons, seven more than DHQ52. Similarly, JH6 can encode up to 9 and 1/3 codons, five more than JH3 and JH4. Thus, in addition to the absence of D-D joins, the absence of long HCDR3 intervals could be attributed to the rare use of DHDXP, DHDLR, and JH6 in the fetus. However, DXP and DLR gene segments are used in fetal life, albeit at a lower frequency than in the adult. It might be expected, therefore, that the lengths of HCDR3s that use these longer gene segments would approximate the distribution seen in the adult. Unexpectedly, we found that the average length of the CDR3 intervals of non-DHQ52-containing VDJ transcripts from second trimester fetal liver was slightly shorter than those that contained DHQ52 (12.1 codons versus 13.2 codons, respectively). There were distinct differences in N region addition between the VDJ joins that contained DHQ52 and those that did not. Although N region addition at the V → D junction was present in the vast majority of second trimester μ transcripts, N nucleotide addition and P junctions were common only in D → J junctions that contain DHQ525. Thus, the restrictions in the length of sequences that used DXP gene segments were due, in part, to a paucity of N region.

In order to determine if these differences in N region addition were solely due to selection of the protein product, DJ transcripts from fetal and adult tissues were examined. The pattern of N region and P junction addition in the DJ transcripts also mirrored their presence in VDJ transcripts. By definition, addition of P nucleotides requires that the rearranging gene segment be of full length13. Of the 53 DHDXP DJ transcripts, only one was full length and it lacked P junction sequence. In contrast, of the 51 DHQ52 DJ transcripts, half contained full length DH sequence and more than three-fourths of these rearrangements contained P junctions. The proportion of sequences that lacked N nucleotides also differed between DJ transcripts that used DHDXP and DHQ52. In seven-week fetal liver, none of the DHDXP DJ transcripts and approximately a quarter of the DHQ52 transcripts lacked N region addition. In 12-week fetal liver, half of the DHDXP DJ transcripts lacked N nucleotides, whereas less than 20% of the DHQ52 DJ transcripts lacked N nucleotides. In 19-week fetal bone marrow pre-B cells, 40% of the DHDXP DJ transcripts lacked N nucleotides, all of the DHQ52 DJ transcripts had N. Finally, in adult bone marrow, 25% of the DHDXP DJ transcripts still lacked N nucleotides, whereas virtually all of the DHQ52 DJ transcripts had N nucleotides.

We evaluated sequences of Feeney36 to determine if N region addition would lead to an increase in the length of mouse HCDR3. As in the human, germline DH gene segments in the mouse differ in length. DHQ52 contains only 10 nucleotides, encoding at most 3 1/3 amino acids. All of the DSP gene segments, as well as DFL16.2, are 17 nucleotides in length, encoding at most 5 2/3 amino acids. DFL16.1 is 23 nucleotides in length, encoding up to 7 2/3 amino acids. In the absence of N region addition, it would be expected that the average length of CDR3 would differ by gene segment. A re-analysis of CDR3 diversity by DH gene segment in VDJ rearrangements previously reported by Feeney and colleagues36 reveals that on average DSP-containing fetal sequences contain three codons more than those with DQ52 (10.8 ± 1.8 versus 7.8 ± 1.6); and that in turn DFL16.1 containing sequences (13.1 ± 1.4) are 2.5 codons longer than those with DSP. However, in the adult there is no significant difference in CDR3 length no matter which DH is used. HCDR3 length for DHQ52 rose to 10.6 ± 1.9, DSP increased slightly to 11.1 ± 2.8, whereas DFL16.1 fell to 11.8 ± 2.2. Thus, all of these DH gene segments generated HCDR3 lengths of approximately 11 amino acids — which is also the average length in the fetus if one includes DFL16.1 and DHQ52 sequences together with those using DSP. Thus, N region addition normalized HCDR3 length.

The mechanisms that control HCDR3 length remain unclear. However, it would appear that human fetal HCDR3 intervals are limited to the range seen in mouse, creating yet more similarities between the human and mouse fetal repertoires. This restriction appears to be relaxed prior to the time of birth. The significance of this change remains unknown.

SUMMARY

The fetal repertoires of mice and humans contain highly similar VH gene segments. Although the details may differ, both species limit the composition of HCDR3. The fetal repertoire is enriched for polyreactive sequences of low affinity. We propose that these sequence and structural limitations are the basis for the characteristic features of the fetal antibody repertoire specificities. Limitations in the size of CDR3 results in a ‘flat’ antibody binding site. Such a ‘flat’ site would maximize the number of different interactions possible between the residues of the CDR3 and potential antigens, resulting in polyspecificity. However, the lack of topography would prevent a tight conformational fit — explaining the low affinity. A highly charged flat surface or a highly non-polar surface would defeat the purpose of such an antigen binding site. Charge or hydrophobicity alone would result in binding of relatively high affinity, but it would restrict binding to a smaller set of determinants. In contrast, selection for neutral, polar amino acids, such as tyrosine, threonine, or serine, would allow formation of low affinity hydrogen bonds between the antibody and a wide array of antigens — i.e. polyspecificity with low affinity, the defining characteristics of the specificity of the ‘fetal’ repertoire.

References

- 1.Paton JC, Toogood IR, Cockington RA, Hansman DJ. Antibody response to pneumococcal vaccine in children aged 5 to 15 years. American Journal of Diseases of Childhood. 1986;140:135–138. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140160053031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein KE. Thymus-independent and thymus-dependent responses to polysaccharide antigens. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1992;165:S49–S52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165-supplement_1-s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverstein AM. Ontogeny of the immune response: a perspective. In: Cooper MD, editor. Development of Host Defense. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1977. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroeder HW, Jr, Perlmutter RM. Development of the human antibody repertoire. In: Gupta S, Griscelli C, editors. New Concepts in Immunodeficiency Diseases. Chichester; 1993. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder HW, Jr, Mortari F, Shiokawa S, Kirkham PM, Elgavish RA, Bertrand FEI. Developmental regulation of the human antibody repertoire. Annals of the New York Academy Sciences. 1995;764:242–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb55834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. 5. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 1991. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirkham PM, Schroeder HW., Jr Antibody structure and the evolution of immunoglobulin V gene segments. Seminars in Immunology. 1994;6:347–360. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leder P. The genetics of antibody diversity. Scientific American. 1982;246(5):102–115. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0582-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575–581. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honjo T. Immunoglobulin genes. Annual Review of Immunology. 1983;1:499–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.002435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancopoulos GD, Alt FW. Regulation of the assembly and expression of variable region genes. Annual Review of Immunology. 1986;4:339–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gathings WE, Kubagawa H, Cooper MD. A distinctive pattern of B cell immaturity in perinatal humans. Immunology Reviews. 1981;57:107–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1981.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lafaille JJ, DeCloux A, Bonneville M, Takagaki Y, Tonegawa S. Junctional sequences of T cell receptor γδ genes: Implications for γδ T cell lineages and for a novel intermediate of V–(D)–J joining. Cell. 1989;59:859–870. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desiderio SV, Yancopoulos GD, Paskind M, et al. Insertion of N regions into heavy-chain gene is correlated with expression of terminal deoxytransferase in B cells. Nature. 1984;311:752–755. doi: 10.1038/311752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Spellerberg MB, Stevenson FK, Capra JD, Potter KN. The I binding specificity of human VH 4–34 (VH 4–21) encoded antibodies is determined by both VH framework 1 and complementarity determining region 3. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;256:577–589. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jack HM, Hartwell L, Beck-Engeser G, et al. Early B cell development depends on the ability of a mu chain to assemble with surrogate light chain. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1997;99:S100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitamura D, Kudo A, Schaal S, Muller W, Melchers F, Rajewsky K. A critical role of lambda 5 protein in B cell development. Cell. 1992;69:823–831. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90293-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiegs SL, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;177:1009–1020. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radic MZ, Erikson J, Litwin S, Weigert M. B lymphocytes may escape tolerance by revising their antigen receptors. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;177:1165–1173. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maretensson L, Fudenberg HH. Gm Genes and gammaG-globulin synthesis in the human fetus. Journal of Immunology. 1965;94:514–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverstein AM, Uhur JW, Kraner KL, Lukes RJ. Fetal response to antigenic stimulus. II. antibody production by the fetal lamb. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1963;117:799–812. doi: 10.1084/jem.117.5.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherwin WK, Rowlands DT., Jr Development of humoral immunity in lethally irradiated mice reconstituted with fetal liver. Journal of immunology. 1974;113:1353–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klinman NR, Press JL. The B cell specificity repertoire: its relationship to definable subpopulations. Transplantation Reviews. 1975;24:41–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1975.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhr JW, Dancis J, Franklin EC, Finkelstein MS, Lewis EW. The antibody response to bacteriophage phiX174 in newborn premature infants. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1962;41:1509. doi: 10.1172/JCI104606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owen JJT, Raff MC, Cooper MD. Studies on the generation of B lymphocytes in the mouse embryo. European Journal of Immunology. 1976;5:468–473. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830050708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancopoulos GD, Desiderio SV, Paskind M, Kearney JF, Baltimore D, Alt FW. Preferential utilization of the most JH-proximal VH gene segments in pre-B cell lines. Nature. 1984;311:727–733. doi: 10.1038/311727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlmutter RM, Kearney JF, Chang SP, Hood LE. Developmentally controlled expression of immunoglobulin VH genes. Science. 1985;227:1597–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.3975629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawler AM, Lin PS, Gearhart PJ. Adult B-cell repertoire is biased toward two heavy-chain variable region genes that rearrange frequently in fetal pre-B cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences US A. 1987;84:2454–2458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malynn BA, Yancopoulos GD, Barth JE, Bona CA, Alt FW. Biased expression of JH-proximal VH genes occurs in the newly generated repertoire of neonatal and adult mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1990;171:843–859. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huetz F, Carlsson L, Tornberg UC, Holmberg D. V-region directed selection in differentiating B lymphocytes. EMBO Journal. 1993;12:1819–1826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dildrop R, Krawinkel U, Winter E, Rajewsky K. VH gene expression in murine lipopolysaccharide blasts distributes over the nine known VH-gene groups and may be random. European Journal of Immunology. 1985;15:1154–1156. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830151117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yancopoulos GD, Malynn BA, Alt FW. Developmentally regulated and strain-specific expression of murine VH gene families. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1988;168:417–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freitas AA, Burlen O, Coutinho AA. Selection of antibody repertoires by anti-idiotypes can occur at multiple steps of B cell differentiation. Journal of Immunology. 1988;140:4097–4102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freitas AA, Viale AC, Sundblad A, Heusser C, Coutinho AA. Normal serum immunoglobulins participate in the selection of peripheral B-cell repertoires. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences US A. 1991;88:5640–5644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu H, Forster I, Rajewsky K. Sequence homologies, N sequence insertion and JH gene utilization in VH-D-JH joining: implications for the joining mechanism and the ontogenetic timing of Ly1 B cell and B-CLL progenitor generation. EMBO Journal. 1990;9:2133–2140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feeney AJ. Lack of N regions in fetal and neonatal mouse immunoglobulin V-D-J junctional sequences. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1990;172:1377–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.5.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vakil M, Kearney JF. Functional characterization of monoclonal auto-anti-idiotype antibodies isolated from the early B cell repertoire of BALB/c mice. European Journal of Immunology. 1986;16:1151–1158. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichihara Y, Hayashida H, Miyazawa S, Kurosawa Y. Only DFL16, DSP2, and DQ52 gene families exist in mouse immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci, of which DFL16 and DSP2 originate from the same primordial DH gene. European Journal of Immunology. 1989;19:1849–1854. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu H, Kitamura D, Rajewsky K. B cell development regulated by gene rearrangement: arrest of maturation by membrane-bound Dmu protein and selection of DH element reading frames. Cell. 1991;65:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90406-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loffert D, Ehlich A, Muller W, Rajewsky K. Surrogate light chain expression is required to establish immunoglobulin heavy chain allelic exclusion during early B cell development. Immunity. 1996;4:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shlomchik MJ, Mascelli MA, Shan H, et al. Anti-DNA antibodies from autoimmune mice arise by clonal expansion and somatic mutation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1990;171:265–297. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raaphorst FM, Raman CS, Nall BT, Teale JM. Molecular mechanisms governing reading frame choice of immunoglobulin diversity genes (reviewed in Ref. 58) Immunology Today. 1997;18:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dighiero G, Lymberi P, Holmberg D, Lundkvist I, Coutinho AA, Avrameas S. High frequency of natural autoantibodies in normal newborn mice. Journal of lmmunology. 1985;134:765–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmberg D, Wennerstrom G, Andrade L, Coutinho AA. The high idiotypic connectivity of ‘natural’ newborn antibodies is not found in adult mitogen-reactive B cell repertoires. European Journal of Immunology. 1986;16:82–87. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kearney JF, Vakil M, Nicholson N. Non-random VH gene expression and idiotype anti-idiotype expression in early B cells. In: Kelsoe G, Schulze D, editors. Evolution and Vertebrate Immunity: The Antigen Receptor and MHC Gene Families. 1. Texas University Press; Austin: 1987. pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gathings WE, Lawton ARI, Cooper MD. Immunofluorescent studies of the development of pre-B cells, B lymphocytes and immunoglobulin isotype diversity in humans. European Journal of Immunology. 1977;7:804–810. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830071112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder HW, Jr, Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Early restriction of the human antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:791–793. doi: 10.1126/science.3118465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schroeder HW, Jr, Wang J-Y. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1990;87:6146–6150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Logtenberg T, Young FM, Van Es JH, Gmelig-Meyling FHJ, Alt FW. Autoantibodies encoded by the most JH-proximal human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region gene. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1989;170:1347–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Es JH, Raaphorst FM, van Tol MJ, Meyling FH, Logtenberg T. Expression pattern of the most JH-proximal human VH gene segment (VH6) in the B cell and antibody repertoire suggests a role of VH6-encoded IgM antibodies in early ontogeny. Journal of Immunology. 1993;150:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ollo R, Sikorav JL, Rougeon F. Structural relationships among mouse and human immunoglobulin VH genes in the subgroup III. Nucleic Acids Research. 1983;11:7887–7897. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.22.7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dighiero G, Lymberi P, Mazie JC, et al. Murine hybridomas secreting natural monoclonal antibodies reacting with self antigens. Journal of Immunology. 1983;131:2267–2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Carroll WL. Restricted Ig H chain V gene usage in the human antibody response to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. Journal of Immunology. 1991;147:1667–1674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dersimonian H, Schwartz RS, Barrett KJ, Stollar BD. Relationship of human variable region heavy chain germ-line genes to genes encoding anti-DNA autoantibodies. Journal of Immunology. 1987;139:2496–2501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen PP, Liu MF, Sinha S, Carson DA. A 16/6 idiotype positive anti-DNA antibody is encoded by a conserved VH gene with no somatic mutation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1988;31:1429–1431. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lydyard PM, Quartey-Papafio R, Williams W, et al. The antibody repertoire of early human B-cells II: Expression of anti-DNA-related idiotypes. Journal of Autoimmunity. 1990;3:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(90)90005-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krishnan MR, Jou NT, Marion TN. Correlation between the amino acid position of arginine in VH-CDR3 and specificity for native DNA among autoimmune antibodies. Journal of Immunology. 1996;157:2430–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Honjo T, Matsuda F. Immunoglobulin heavy chain loci of mouse and human. In: Honjo T, Alt FW, editors. Immunoglobulin Genes. 2. Academic Press; London: 1995. pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cook GP, Tomlinson IM, Walter G, et al. A map of the human immunoglobulin VH locus completed by analysis of the telomeric region of chromosome 14q. Nature Genetics. 1994;7:162–168. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertrand FEI, Billips LG, Burrows PD, Gartland GL, Kubagawa H, Schroeder HW., Jr Immunoglobulin DH gene segment transcription and rearrangement prior to CD19 expression in normal human bone marrow. Blood. 1997;90:736–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greaves MF, Brown J, Molgaard HV, et al. Molecular features of CD34: a hemopoietic progenitor cell-associated molecule (review in Ref 40) Leukemia. 1992;6(Suppl 1):31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamada M, Wasserman R, Reichard BA, Shane SS, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1991;173:395–407. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]