Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to determine whether premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) arising from the aortic sinuses of Valsalva (SOV) and great cardiac vein (GCV) have coupling interval (CI) characteristics that differentiate them from other ectopic foci.

Background

PVCs occur at relatively fixed CI from the preceding normal QRS complex in most patients. However, we observed patients with PVCs originating in unusual areas (SOV and GCV) in whom the PVC CI was highly variable. We hypothesized that PVCs from these areas occur seemingly randomly because of the lack of electrotonic effects of the surrounding myocardium.

Methods

Seventy-three consecutive patients referred for PVC ablation were assessed. Twelve consecutive PVC CIs were recorded. The ΔCI (maximum – minimum CI) was measured.

Results

We studied 73 patients (age 50 ± 16 years, 47% male). The PVC origin was right ventricular (RV) in 29 (40%), left ventricular (LV) in 17 (23%), SOV in 21 (29%), and GCV in 6 (8%). There was a significant difference between the mean ΔCI of RV/LV PVCs compared with SOV/GCV PVCs (33 ± 15 ms vs. 116 ± 52 ms, p < 0.0001). A ΔCI of >60 ms demonstrated a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, and negative predictive value of 94%. Cardiac events were more common in the SOV/GCV group versus the RV/LV group (7 of 27 [26%] vs. 2 of 46 [4%], p < 0.02).

Conclusions

ΔCI is more pronounced in PVCs originating from the SOV or GCV. A ΔCI of 60 ms helps discriminate the origin of PVCs before diagnostic electrophysiological study and may be associated with increased frequency of cardiac events.

Keywords: aortic sinus of Valsalva, oupling interval, great cardiac vein, premature ventricular contraction

Idiopathic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are generally considered benign and are often treated conservatively. However, sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), symptomatic PVCs resistant to medical therapy, and PVCs thought to contribute to an underlying cardiomyopathy are often treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Noninvasive mapping criteria based on 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) characteristics can help with procedural planning and guide mapping if RFA is needed (1–13). However, PVCs with a V3 precordial ECG transition are difficult to localize and can be of right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) or left ventricular outflow tract origin (14).

The reportedly benign nature of outflow idiopathic PVCs has been disputed by some (15). There is reasonable evidence that a small proportion of these cases may be higher risk for R-on-T phenomena and sudden cardiac death (SCD). However, limited data exist to help the clinician risk stratify on the basis of PVC characteristics.

PVCs occur at relatively fixed coupling intervals (CIs) from the preceding normal QRS complex in most patients. However, we observed some patients with PVCs originating in unusual areas (aortic sinuses of Valsalva [SOV], great cardiac vein [GCV]) in whom the PVC CI was highly variable. We hypothesized that PVCs from these areas could occur seemingly randomly because of the lack of restraining electrotonic coupling effects of the surrounding myocardium. We also hypothesized that this variable CI characteristic might be a valuable diagnostic tool as well as provide further insights into the functional behavior of these PVCs and possible cardiac event risk associated with a given PVC origin.

Methods

Consecutive cases of idiopathic PVCs that were mapped and ablated were assessed. Only cases with PVCs with a frequency of >10/min were studied. However, the majority had a pattern of bigeminy or trigeminy. Cases with rare PVCs or only nonsustained or sustained VT were excluded, as were cases of fascicular PVC/VT. Patients with cardiomyopathy were excluded if the PVCs were thought to be secondary to the underlying cardiomyopathy. Cases of cardiomyopathy thought secondary to a high burden of PVCs were included as long as alternative etiologies of cardiomyopathy such as severe obstructive coronary artery or significant valvular disease were ruled out. Approval for enrollment into the study was obtained from the respective institutional review boards.

Antiarrhythmic medications were discontinued at least 48 h before the procedure as per protocol at the participating institutions. Surface ECG leads from the diagnostic electrophysiological study were analyzed using electronic calipers at a 100 mm/s sweep speed. Only monomorphic PVCs were studied. The first available period in the diagnostic study during which 12 consecutive PVCs were available for analysis was assessed. The interval from the initial Q- or R-wave of the preceding sinus beat to the beginning of the subsequent PVC beat was measured in milliseconds. The difference in milliseconds between the maximum and minimum CI (ΔCI) was calculated. The first 12 consecutive PVCs were chosen for analysis to limit the effect of procedural sedation later in the study as well as to maximize the clinical utility of any findings, which could potentially translate to evaluation, not only from the diagnostic electrophysiological study, but also from a 12-lead ECG or rhythm strip obtained in a cardiology office or from an outpatient ambulatory ECG monitor.

A standard diagnostic electrophysiological study was then performed using several percutaneously placed multi-electrode catheters. If needed, isoproterenol infusion was used to increase the frequency of PVCs. Mapping of the PVC origin was performed targeting the earliest site of activation compared with the onset of the surface PVC QRS complex, after which RFA was attempted using standard or irrigated radiofrequency energy after excluding an unacceptable proximity to a major coronary artery (e.g., epicardial mapping at the left ventricular [LV] base). In most cases, advanced mapping systems such as CARTO version 3.0 (Biosense-Webster, Diamond Bar, California) or NavX version 3.0 (St. Jude Medical, Minneapolis, Minnesota) were used to facilitate mapping.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and comparison between 2 groups was analyzed using the Student t test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Given the heterogeneity of variance in ΔCI, Welch’s t test was used to compare groups. A receiver-operating characteristic curve was constructed and Youden’s Index applied to determine the optimal cutoff for ΔCI as a diagnostic test.

Results

We studied 73 patients (age 50 ± 16 years, 47% male) (Table 1). The PVC origin was right ventricle (RV) in 29 (40%), LV in 17 (23%), SOV in 21 (29%), and GCV in 6 (8%). Of the RV PVCs, 22 (76%) were from the RVOT with the remainder from the RV body (3 septal, 2 basal inferior, and 2 inferoseptal). Of the LV PVCs, 2 were from the aortomitral continuity, 5 from the anterior wall (2 endocardial and 3 epicardial), 5 from the inferior wall, 3 from the lateral wall, and 1 from the septal wall. Of the SOV PVCs, 1 (5%) originated from the right SOV, 16 (76%) originated from the left SOV, and 4 (19%) originated from the left and right junction. The index PVC was successfully ablated in 68 of 73 (93%) of all cases and in 68 of 69 (99%) of cases in which ablation was attempted. Ablation was deferred because of location near a coronary artery in 4 of 73 (5%).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| SOV/GCV (n = 27) |

RV/LV (n = 46) |

p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 47 ± 18 | 52 ± 15 | 0.25 | ||

| Male | 15 (56) | 19 (41) | 0.46 | ||

| Ejection fraction, % | 47 ± 12 | 50 ± 11 | 0.31 | ||

| PVC origin | SOV | 21 (29) | RV | 29 (40) | |

| Right SOV | 1 (1) | RVOT | 22 (30) | ||

| Left SOV | 16 (22) | RV body | 7 (10) | ||

| L-R junction | 4 (5) | LV | 17 (23) | ||

| GCV | 6 (8) | ||||

| Antiarrhythmic therapy | |||||

| Beta-blockers | 17 (63) | 32 (70) | 0.61 | ||

| Calcium channel blockers | 3 (11) | 3 (7) | 0.66 | ||

| Amiodarone | 2 (7) | 9 (20) | 0.28 | ||

| Other | 4 (15) | 9 (20) | 0.52 | ||

| Previous cardiac event | 7 (26) | 2 (4) | <0.02 | ||

| Previous failed ablation | 10 (37) | 13 (28) | 0.45 | ||

| ICD | 4 (15) | 4 (9) | 0.46 | ||

| Successful ablation | 23 (85) | 45 (98) | 0.06 | ||

| Ablation signal preceding QRS, ms | 31 ± 14 | 28 ± 12 | 0.34 | ||

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

GCV = great cardiac vein; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LV = left ventricle; PVC = premature ventricular complexes; RV = right ventricle; RVOT = right ventricular outflow track; SOV = sinus of Valsalva.

When baseline characteristics were compared on the basis of the location of PVC origin, there was no difference in age (47 ± 18 years vs. 52 ± 15 years, p = 0.25), sex (56% male vs. 41% male, p = 0.46), baseline ejection fraction (47 ± 12% vs. 50 ± 11%, p = 0.31), or baseline PVC burden on ambulatory ECG monitor (24.3 ± 10.5% vs. 23.5 ± 11.4%, p = 0.83) in the SOV/GCV groups versus the RV/LV group, respectively. There was no difference in the proportion of patients taking beta-blockers (63% vs. 70%, p = 0.61), calcium channel blockers (11% vs. 7%, p = 0.66), or standard antiarrhythmic medications (15% vs. 26%, p = 0.36) before the procedure.

Pre-procedure syncope, cardiac arrest, or documented polymorphic VT were more common in the SOV/GCV group versus the RV/LV group (7 of 27 [26%] vs. 2 of 46 [4%], p < 0.02). In the SOV/GCV group, there were 3 SCDs, 1 documented polymorphic VT, and 3 syncopal episodes, whereas in the RV/LV group, there was 1 syncopal episode and 1 implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation for VT (though it was not clear from the available history whether there was any associated syncope or events other than monomorphic VT).

Procedural characteristics were similar, including ablation success, number of radiofrequency applications delivered, type of ablation catheters used, or need for isoproterenol infusion during the procedure. The mean CI was 517 ± 96 ms in the SOV/GCV group versus 512 ± 70 ms in the RV/LV group (p = 0.34).

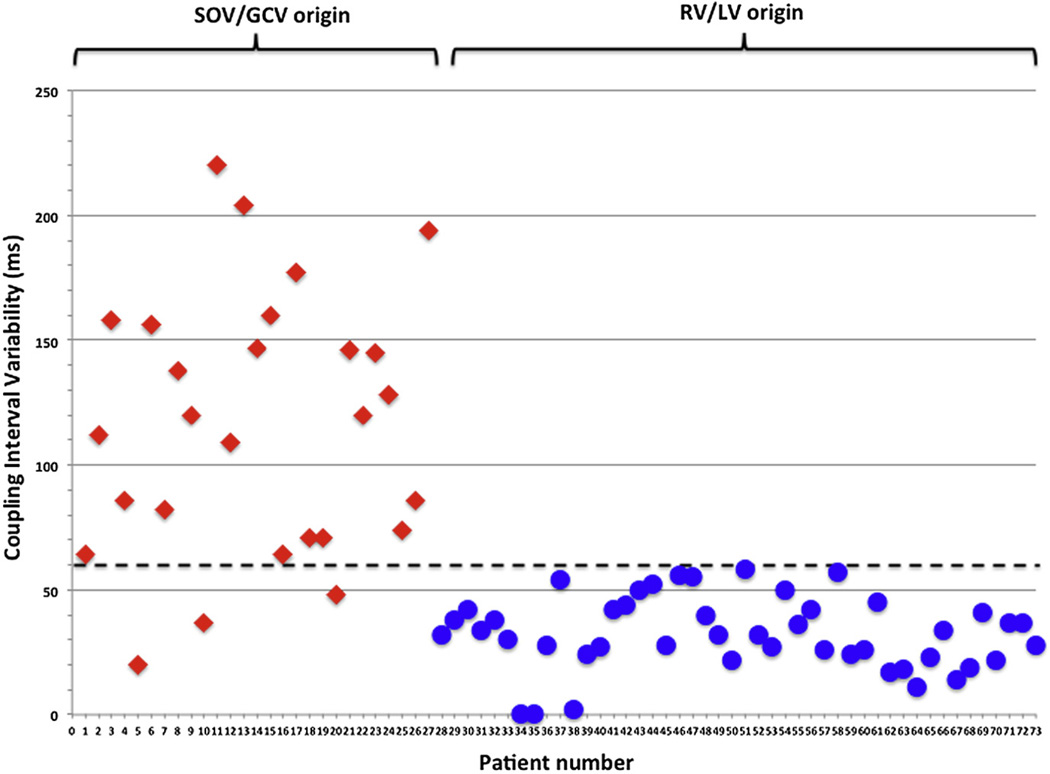

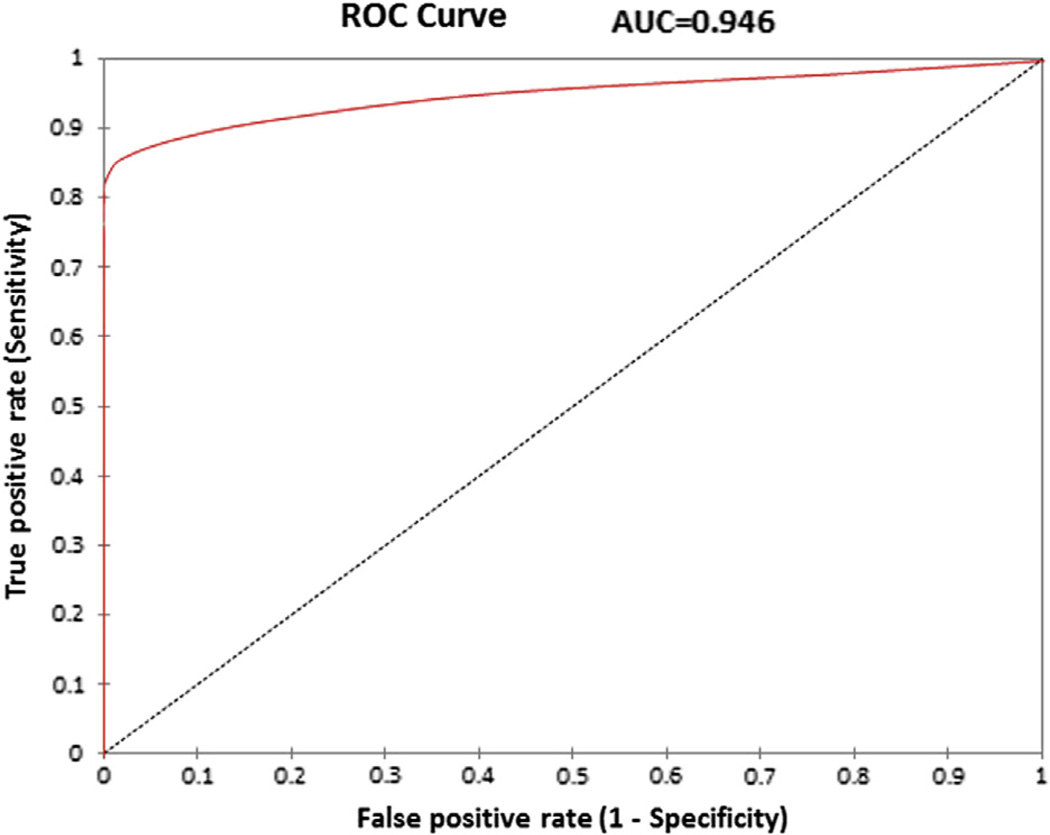

However, there was a significant difference between the mean ΔCI of SOV/GCV origin PVCs (11 ± 52 ms) compared with those arising from the RV/LV (33 ± 15 ms; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). No RV/LV PVCs had a ΔCI >60 ms, and only 3 of the SOV/GCV PVCs had a ΔCI <60 ms. The median ΔCI in the SOV/GCV group was 120 ms (quartile 1 [Q1] = 72.5 ms, Q2 = 120 ms, Q3 = 151.5 ms), whereas the median ΔCI for the RV/LV group was 32 ms (Q1 = 24 ms, Q2 = 32 ms, Q3 = 42 ms). A ΔCI of >60 ms demonstrated a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, and negative predictive value of 94% for SOV/GCV origin of the PVC (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Scatter Plot of ΔCI Demonstrating Variable CI in PVCs Originating From the SOV/GCV But Not in PVCs From the RV/LV.

The scatter plot demonstrates that PVCs originating from the SOV/GCV predominantly have a ΔCI <60 ms, whereas RV/LV origin PVCs consistently have a ΔCI >60 ms with a ΔCI of <60 ms, demonstrating a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, and negative predictive value of 94%. ΔCI = (maximum – minimum) coupling interval; PVC = premature ventricular complexes; RV/LV = right ventricle/left ventricle; SOV/GCV = sinus of Valsalva/great cardiac vein.

Figure 2. ROC Curve.

ROC curve plotting the true positive rate (sensitivity) versus false positive rate (1 – specificity) documenting the ability of ΔCI to differentiate SOV/GCV and RV/ LV origin PVCs with an AUC = 0.946. The ROC curve in combination with Youden’s index supports a ΔCI of <60 ms. A <60-ms cutoff demonstrates a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100%, and negative predictive value of 94%. AUC = area under the curve; ROC = receiver-operating characteristic; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Discussion

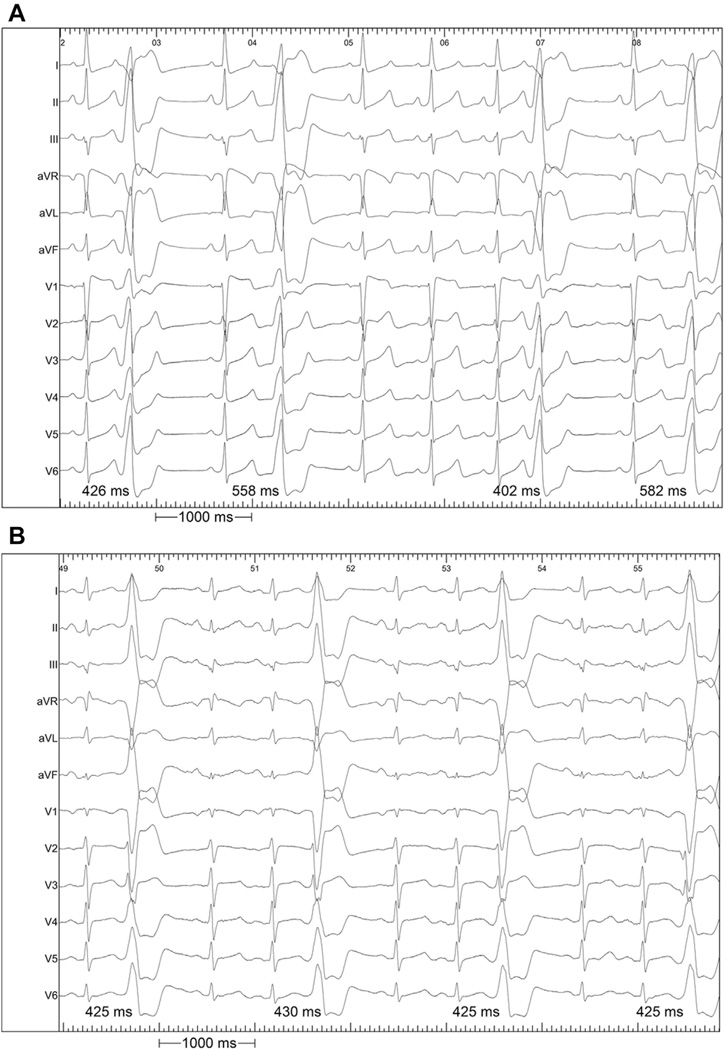

The major findings of this study are: 1) PVCs arising from SOV or GCV sources have highly variable coupling intervals from the prior QRS complex compared with PVCs from other regions (Fig. 3); and 2) in some cases, PVCs from the SOV/GCV may have different, and more malignant, clinical behavior from PVCs arising elsewhere. Thus, the ECG provides an important clue to the identification of the anatomic location and functional behavior of the arrhythmia.

Figure 3. 12-Lead ECGs Demonstrating Examples of PVCs With Variable and Fixed Coupling.

An example of (A) variable CI seen in a SOV/GCV source; and (B) stable CI of an RVOT source are shown. ECG = electrocardiogram; RVOT = right ventricular outflow tract; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Mechanism of arrhythmia and CI

The majority of PVCs occur at relatively fixed CI from the prior QRS complex, though a complete understanding of the determinants of CI duration and variability are limited in the literature. Our findings show that PVCs originating in the SOV and GCV behave differently than other idiopathic PVCs. Although most idiopathic PVCs do not behave like true parasystoles, the reason why SOV/GCV PVCs have variable coupling in relation to the preceding sinus beat compared with RV/LV PVCs may partly be related to different aspects on the continuum of parasystolic behavior.

A parasystole is an ectopic focus that discharges at relatively fixed intervals that are integral multiples of a fundamental interval and are not related to the preceding sinus beat, because of entrance block into the focus such that its rate of discharge cannot be reset (16,17). However, even when a parasystolic focus is suspected, the occurrence of ectopic complexes is not always at a precisely predictable interval (multiples of a basic interval). Numerous mechanisms have been postulated to explain nonfixed parasystolic activity, including variable amounts of entrance block to the parasystolic focus (18), as well as subthreshold stimulation from surrounding myocytes via electrotonic interaction (19). No cases in our series behaved as true parasystoles. However, unique anatomic characteristics of PVCs from these sites may cause SOV/GCV PVCs to have some characteristics that are thought to be related to parasystolic foci and therefore cause the variable coupling that was seen.

Anatomic location

Our data suggested that relative anatomic isolation of SOV/GCV PVCs may be associated with variable CI. Gami et al. (20) have demonstrated that myocardial extensions above the semilunar valves are common and help explain the occurrence of SOV PVCs. In a series of 603 autopsy hearts, such extensions (isolated strands of muscle) were seen above the aortic valve in the SOV in 57%. Fifty-four percent had extensions above the right coronary cusp and 24% above the left coronary cusp. Extensions above the non-coronary cusp were rare (0.66%). Extensions in the right coronary cusp (2.8 ± 1.2 mm) and left coronary cusp (1.5 ± 0.5 mm) were relatively narrow. Extensions can be seen in the aortic wall, in the valve leaflet itself, or in the intercuspal region. How this unique anatomy with narrow myocardial extensions can be the source of PVCs, and how it affects PVC behavior, are not well understood.

Anatomic location–function interactions

We postulate that PVCs originating from sites within narrow, relatively isolated muscle fibers such as the SOV and GCV may behave more similarly to a modulated parasystolic focus than to a more typical PVC focus, and that this behavior may explain the differences in ΔCI. Lacking large amounts of surrounding myocardium to provide electrotonic inhibition, the narrow muscle strands in the SOV and extending along the GCV may be more prone to partial entrance block. PVCs from the RV/LV outflow (below the valve) or body with extensive surrounding myocardium (and without localized fibrosis) would not be expected to behave in this manner. This relative isolation may decrease the modulation of the PVC focus by the sinus rhythm focus as described recently by Takayanagi et al. (21).

Electrotonic interaction is thought to affect the firing of ectopic foci through interaction, not only between cardiomyocytes (19,22,23), but also potentially between nearby and distant myofibroblasts and cardiomyocytes through connexins (24–28).

Electrotonic influences can delay the discharge of ectopic foci if they arrive early in the diastolic depolarization window, and can accelerate the firing of the focus if the impulse arrives late in the diastolic depolarization window. Jalife and Moe (19) demonstrated in 1976 that sufficient myocardial tissue in the region near a parasystolic focus can have significant effects, with variability up to 40% in the ectopic cycle length.

The source–sink interplay of electrotonic interaction largely controls the firing of ectopic foci. The current of the ectopic source must overcome the activation threshold of the surrounding cells that are repolarized. The more surrounding cells that are repolarized (sink), the more difficult it is for the ectopic focus (source) to overcome the mismatch because current flows from the repolarized cells to the cells attempting to depolarize. Therefore, the more surrounding cells a focus has, the more “controlled” that focus may be. Although all discharges from PVC foci that form a QRS complex must by definition overcome the source–sink mismatch, intuitively, it is possible that foci with fewer surrounding myocytes are under less external influence than foci surrounded by dense myocardium. Uncoupling may even allow depolarization wave fronts to overcome source– sink mismatch (29).

Because of the limited understanding of the determinants of PVC coupling, the preceding explanation is only a postulation and cannot be proven at this time. Other plausible explanations exist for this CI behavior, including raterelated influences on triggered activity and the anatomic relationship of the PVC focus to the His-Purkinje system, and potential concealed re-entry involving the fascicular branches for those PVCs arising near the conduction system leading to fixed CI.

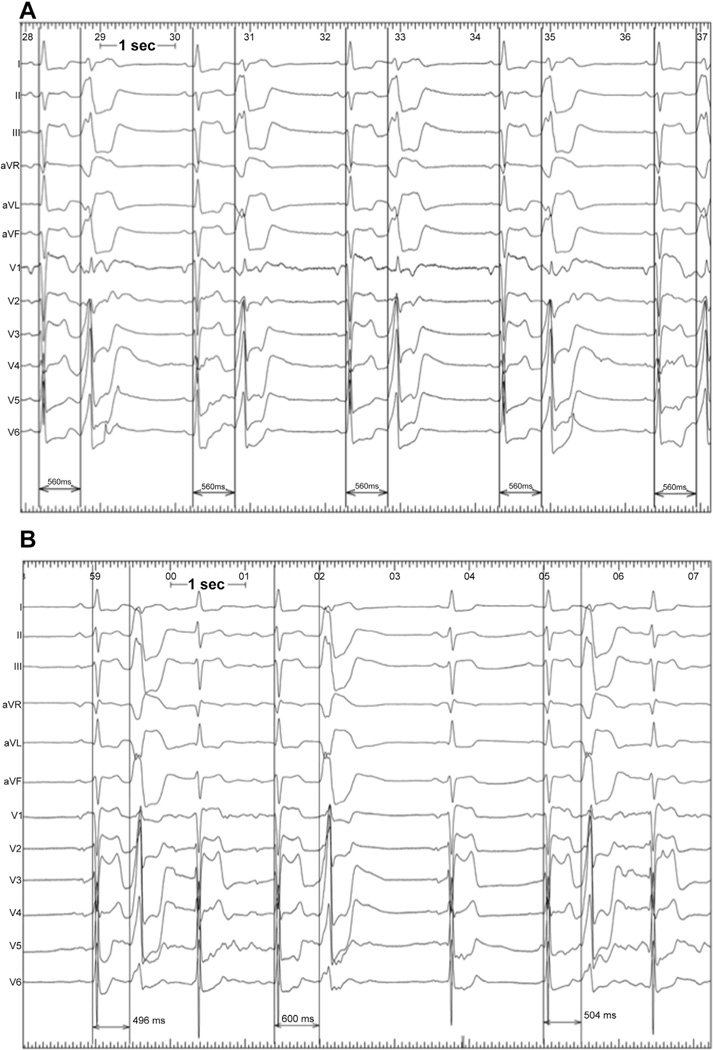

However, Figure 4 shows an example of a type of case seen in a number of instances that we believe supports our mechanistic hypothesis. In this case (not part of this series), initial extensive epicardial ablation of a mid-myocardial LV PVC with fixed coupling did not eliminate the PVC but rather caused uncoupling. A second procedure 3 months later with further ablation on the endocardial aspect of the thick anterior LV wall (equally early signals from each surface) eliminated the PVC. We believe this phenomenon likely occurred because the epicardial site of ablation was too far from the PVC site of origin to completely eliminate the PVC, but the extensive ablation decreased the amount of surrounding viable myocardium near the PVC focus, causing decreased electrotonic restraining effect and increased entrance block into the focus.

Figure 4. 12-Lead ECGs Demonstrating Examples of PVCs With Variable and Fixed Coupling Related to Unsuccessful Ablation.

An example of an ECG of a PVC in a patient that shows (A) stable coupling before ablation; and (B) variable coupling after initial failed ablation attempt. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

In addition to the potential diagnostic utility of PVCs with variable CI (pointing to a SOV/GCV source), we postulate that patients with this finding may be predisposed to higher risk of cardiac arrhythmic events (syncope, SCD), as was seen in our study. Sosnowski et al. (30) demonstrated that the PVC CI assessed on a 24-h ambulatory monitor in patients with coronary artery disease was associated with an increased risk of cardiac mortality. Viskin et al. (15) have described a short-coupled variant of RVOT PVCs. The mean CI of our cases was longer than described by Viskin and colleagues; however, the ΔCI was not assessed in their study.

Study limitations

First, the patient population was relatively small, with a limited number of cases of PVCs arising in the SOV/GCV regions. Despite this, the differences between ΔCI in these patients versus those with PVCs arising in other areas were striking. In particular, interpretation may be limited for right coronary cusp PVCs because only 1 case was included in the series. Second, it is possible that if we had measured more CIs (>12) in each patient, the differences between groups would have decreased. However, the standard deviation of CI among individual patients with PVCs from non-SOV/GCV regions was small and unlikely to increase with more sampling. It is not known whether CIs vary over the course of a procedure or throughout the day. To minimize this uncertainty and to make the findings applicable to a resting state outside of the electrophysiology laboratory, we measured consecutive CIs at the beginning of all procedures before significant anesthesia was given. We believe that the current protocol increases the likelihood that these findings can be translated to analyzing a resting ECG done in a cardiology office. Third, PVCs successfully ablated in the GCV may have originated within the venous system itself, but we cannot rule out the possibility that the origin was within the epicardial LV summit muscle, but close enough to the GCV that ablation was clinically successful. Finally, PVCs originating from the papillary muscles are not included in this series, and therefore, conclusions regarding the behavior of papillary muscle PVCs cannot be made based on the current study.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the ΔCI of idiopathic PVCs, easily measured from the ECG, may be a useful diagnostic tool to determine the origin of idiopathic PVCs and aid in planning ablation procedure strategy. The CI variability seen in SOV/GCV sources raises concerns that PVCs with such variability may be associated with a higher risk for cardiac events. Further study is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL084261 to Dr. Shivkumar). Dr. Miller has received fellow training grants from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Biosense-Webster; speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Biosense-Webster, St. Jude Medical, and Biotronik; and is a scientific advisor (without compensation) for Topera.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ΔCI

coupling interval

- CI

coupling interval

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- GCV

great cardiac vein

- LV

left ventricle/ventricular

- PVC

premature ventricular complexes

- Q

quartile

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- RV

right ventricle/ventricular

- RVOT

right ventricular outflow tract

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- SOV

sinus of Valsalva

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ouyang F, Fotuhi P, Ho SY, et al. Repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia originating from the aortic sinus cusp: electrocardiographic characterization for guiding catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:500–508. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanagaratnam L, Tomassoni G, Schweikert R, et al. Ventricular tachycardias arising from the aortic sinus of Valsalva: an under-recognized variant of left outflow tract ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada T, Yoshida N, Murakami Y, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics of ventricular arrhythmias originating from the junction of the left and right coronary sinuses of Valsalva in the aorta: the activation pattern as a rationale for the electrocardiographic characteristics. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamada T, McElderry HT, Doppalapudi H, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the aortic root prevalence, electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characteristics, and results of radiofrequency catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bala R, Garcia FC, Hutchinson MD, et al. Electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic features of ventricular arrhythmias originating from the right/left coronary cusp commissure. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betensky BP, Park RE, Marchlinski FE, et al. The v(2) transition ratio: a new electrocardiographic criterion for distinguishing left from right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia origin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2255–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sekiguchi Y, Aonuma K, Takahashi A, et al. Electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characteristics of ventricular tachycardia originating within the pulmonary artery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tada H, Tadokoro K, Ito S, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the tricuspid annulus: prevalence, electrocardiographic characteristics, and results of radiofrequency catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Herendael H, Garcia F, Lin D, et al. Idiopathic right ventricular arrhythmias not arising from the outflow tract: prevalence, electrocardiographic characteristics, and outcome of catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tada H, Ito S, Naito S, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmia arising from the mitral annulus: a distinct subgroup of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida N, Inden Y, Uchikawa T, et al. Novel transitional zone index allows more accurate differentiation between idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract and aortic sinus cusp ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels DV, Lu YY, Morton JB, et al. Idiopathic epicardial left ventricular tachycardia originating remote from the sinus of valsalva: electrophysiological characteristics, catheter ablation, and identification from the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Circulation. 2006;113:1659–1666. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baman TS, Ilg KJ, Gupta SK, et al. Mapping and ablation of epicardial idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias from within the coronary venous system. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:274–279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.910802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanner H, Hindricks G, Schirdewahn P, et al. Outflow tract tachycardia with R/S transition in lead V3: six different anatomic approaches for successful ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:418–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viskin S, Rosso R, Rogowski O, Belhassen B. The “short-coupled” variant of right ventricular outflow ventricular tachycardia: a not-so-benign form of benign ventricular tachycardia? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:912–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.50040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pick A, Langendorf R. Parasystole and its variants. Med Clin North Am. 1976;60:125–147. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langendorf R, Pick A. Parasystole with fixed coupling. Circulation. 1967;35:304–315. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinoshita S, Katoh T, Mitsuoka T, Hanai T, Tsujimura Y, Sasaki Y. Ventricular parasystolic couplets originating in the pathway between the ventricle and the parasystolic pacemaker: mechanism of “irregular” parasystole. J Electrocardiol. 2001;34:251–260. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2001.24768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalife J, Moe GK. Effect of electrotonic potentials on pacemaker activity of canine Purkinje fibers in relation to parasystole. Circ Res. 1976;39:801–808. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gami AS, Noheria A, Lachman N, et al. Anatomical correlates relevant to ablation above the semilunar valves for the cardiac electrophysiologist: a study of 603 hearts. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2011;30:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s10840-010-9523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takayanagi K, Nakahara S, Toratani N, et al. Strong modulation of ectopic focus as a mechanism of repetitive interpolated ventricular bigeminy with heart rate doubling. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trautwein W, Kassebaum DG. On the mechanism of spontaneous impulse generation in the pacemaker of the heart. J Gen Physiol. 1961;45:317–330. doi: 10.1085/jgp.45.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidmann S. Effect of current flow on the membrane potential of cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1951;115:227–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyde A, Blondel B, Matter A, Cheneval JP, Filloux B, Girardier L. Homo- and heterocellular junctions in cell cultures: an electrophysiological and morphological study. Prog Brain Res. 1969;31:283–311. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohl P, Kamkin AG, Kiseleva IS, Noble D. Mechanosensitive fibroblasts in the sino-atrial node region of rat heart: Interaction with cardiomyocytes and possible role. Exp Physiol. 1994;79:943–956. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1994.sp003819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goshima K. Formation of nexuses and electrotonic transmission between myocardial and FL cells in monolayer culture. Exp Cell Res. 1970;63:124–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(70)90339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goshima K. Synchronized beating of and electrotonic transmission between myocardial cells mediated by heterotypic strain cells in monolayer culture. Exp Cell Res. 1969;58:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(69)90523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feld Y, Melamed-Frank M, Kehat I, Tal D, Marom S, Gepstein L. Electrophysiological modulation of cardiomyocytic tissue by transfected fibroblasts expressing potassium channels: a novel strategy to manipulate excitability. Circulation. 2002;105:522–529. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohr S, Kucera JP, Fast VG, Kleber AG. Paradoxical improvement of impulse conduction in cardiac tissue by partial cellular uncoupling. Science. 1997;275:841–844. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sosnowski M, Skrzypek-Wanha J, Korzeniowska B, Tendera M. Increased variability of the coupling interval of premature ventricular beats may help to identify high-risk patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2004;94:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]