Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this ongoing randomized study was to assess differences in bone level changes and success rates using implants supporting single crowns in the posterior mandible either with platform matched or platform switched abutments.

Material and Methods

Patients aged 18 and above, missing at least two teeth in the posterior mandible and with a natural tooth mesial to the most proximal implant site were enrolled. Randomization followed implant placement. Definitive restorations were placed after a minimum transgingival healing period of 8 weeks. Changes in crestal bone level from surgery and loading (baseline) to 12-month post-loading were radiographically measured. Implant survival and success were determined.

Results

Sixty-eight patients received 74 implants in the platform switching group and 72 in the other one. The difference of mean marginal bone level change from surgery to 12 months was significant between groups (p < 0.004). Radiographical mean bone gain or no bone loss from loading was noted for 67.1% of the platform switching and 49.2% of the platform matching implants. Implant success rates were 97.3% and 100%, respectively.

Conclusions

Within the same implant system the platform switching concept showed a positive effect on marginal bone levels when compared with restorations with platform matching.

Keywords: crestal bone preservation, implant success, platform matching, platform switching, randomized clinical trial

Conflict of interest and source of funding statement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests related to this study.

This study was funded by an unrestricted grant of the Camlog Foundation, Basel, Switzerland. Prof. F. Guerra and Prof. W. Wagner are members of the Camlog Foundation Board.

Crestal bone loss around dental implants has been attributed to several factors. Stress-concentration after implant loading, the countersinking during implant placement procedures and localized soft-tissue inflammation are certain factors among others (Oh et al. 2002). Their specific role in marginal bone level alteration is still subject of current research. The potential benefit of platform switching (PS) was discovered casually due to a production delay of prosthetic components. Radiographs of the restored implants exhibited minimal alveolar crestal bone remodeling (Lazzara & Porter 2006). The authors assumed that through the inward positioning of the implant/abutment junction: (i) the distance of the junction in relation to the adjacent crestal bone and (ii) the surface area to which the soft tissue can attach and establish a biological width was increased and therefore bone resorption at the implant-abutment junction associated with the inflammatory cell infiltrate was reduced.

Other authors introduced this characteristic implant/abutment interface mismatch as a valuable treatment option (Luongo et al. 2008). The treatment concept of PS has been developed. The biological processes (Lazzara & Porter 2006) and biomechanics (Maeda et al. 2007, Schrotenboer et al. 2009, Chang et al. 2010) proposed to be associated with PS also contributed to the growing clinical application of this concept. The market responded to the putative success of PS with the release of implants either with horizontal flat, outward inclined or inward oblique mismatch supported by few scientific data.

Further animal and human studies have predominantly measured changes in crestal bone levels not always demonstrating a positive effect of PS. Whereas PS with minimal bone loss could be observed on radiographs of implants inserted in the jaw of dogs by Jung et al. (2008) and on histological preparations by Cochran et al. (2009), no statistically significant differences could be verified between the two treatment concepts in related animal studies conducted by Becker et al. (2007, 2009).

Biomechanical simulations using finite element analyses at implants with PS suggested a reduction of the loading stress at the bone-implant interface and therefore in the crestal region of the cortical bone via transferring it along the implant axis to the cancellous bone (Maeda et al. 2007, Schrotenboer et al. 2009, Chang et al. 2010).

Furthermore, the reduced size of bone loss seems to be inversely correlated to the extent of the horizontal platform mismatch (Canullo et al. 2010a and Cocchetto et al. 2010) and to be independent of the bacterial composition of the biofilm since the peri-implant microbiota at implants with and without PS was almost indistinguishable (Canullo et al. 2010b). In accordance with the beneficial concept of PS, histological human data displayed minimal bone loss and a reduced dimension of the inflammatory cell infiltrate indicated by its limited apical extension beyond the platform in these implants (Degidi et al. 2008, Luongo et al. 2008). Although histological characterization of peri-implant soft tissue biopsies taken from implants 4 years after restoration either with PS or platform matching (PM) abutments was not different in terms of the extent of inflamed connective tissue, the microvascular density and the collagen content, the authors speculated that early soft tissue events such as the formation of the biological width may be different and responsible for the diminished bone loss around PS implants (Canullo et al. 2011).

A systematic review with meta-analysis (Atieh et al. 2010) where PS and PM were reported included 10 controlled clinical trials. Radiographical marginal bone level changes and failure rates after a follow-up period of 12–60 months were evaluated. Only one (Kielbassa et al. 2009) of the 10 studies showed a trend towards better bone level maintenance for the PM implants, without significance. The remaining studies reported favourable results for PS, four as a trend (Hürzeler et al. 2007, Crespi et al. 2009, Trammell et al. 2009, Enkling et al. 2011) and five with statistical significance (Cappiello et al. 2008, Canullo et al. 2009, 2010a, Prosper et al. 2009, Vigolo & Givani 2009). Accordingly, the authors concluded that marginal bone loss for PS was significantly less than around PM implants. No such difference could be found between PS and PM regarding failure rates. Another systematic review included nine articles (Al-Nsour et al. 2012), eight (Cappiello et al. 2008, Canullo et al. 2009, 2010a, Crespi et al. 2009, Kielbassa et al. 2009, Prosper et al. 2009, Trammell et al. 2009, Vigolo & Givani 2009) were already part of the meta-analysis conducted by Atieh et al. (2010) and one article was added (Fickl et al. 2010). In this systematic review no meta-analysis was performed because of the hetero-geneous study designs and implant characteristics of the selected articles. Despite the demonstrated difference between PS and PM, the authors of both systematic reviews as well as others (Serrano-Sánchez et al. 2011) claimed that additional clinical trials are needed to substantially confirm the advantageous effect of PS. Especially because various factors such as implant insertion depth, implant design, implant microstructure and the size of the implant platform were often heterogeneous within the same PS study and might therefore more or less influence the outcomes.

The purpose of this prospective randomized multicenter clinical study (RCT) was to assess the differences in bone level changes between PS and PM restorations using same implants in the same implant indication in both groups. Implants supporting single crowns were inserted in the posterior mandible with fixed dentition in the opposite and restored either with PM or PS abutments. The null hypothesis (H0) was that there is no difference in bone changes between PS and PM between loading and yearly follow-ups.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The prospective multicenter randomized clinical study was performed in three centres located in Germany (two) and Portugal (one). The study was approved by the competent Ethics Committees (FECI 09/1308 and CES/0156) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2008).

Study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients aged 18 and above with two or more adjacent missing teeth in the posterior mandible, a natural tooth mesial to the most proximal implant site, adequate bone quality and quantity at the implant site to permit the insertion of a dental implant and with natural teeth or implant-supported fixed restoration as opposing dentition were included. Free end situations were allowed. All patients signed the detailed informed consent form before surgery.

Individuals who presented uncontrolled systemic diseases or took medication interfering with bone metabolism or presenting abuse of drugs or alcohol, use of tobacco equivalent to more than 10 cigarettes/day or presenting handicaps that would interfere with the ability to perform adequate oral hygiene, or prevent completion of the study participation were excluded. Local exclusion criteria included history of local inflammation, untreated periodontitis, mucosal diseases, local irradiation therapy, history of implant failure as well as unhealed extraction sites, keratinized gingiva less than 4 mm or patient presenting a thin phenotype or parafunctions. Exclusion criteria at surgery were lack of implant primary stability or inappropriate implant position according to prosthetic requirements.

Material

Per randomized site, 2–4 adjacent CAMLOG® SCREW-LINE Implants with a Promote® plus surface (CAMLOG Biotechnologies AG, Basel, Switzerland) were placed. The most coronal part of the implant neck presented a machined part of 0.4 mm. Implant diameter (3.8, 4.3 or 5.0 mm) and length (9, 11, and 13 mm) were selected according to available bone.

Healing abutments, impression posts, and abutments were inserted timely according to the group. The mismatch of the PS group was 0.3 mm for the implants with a diameter of 3.8 and 4.3 mm and 0.35 mm for the implants with a 5.0 mm diameter. All products used were registered products, commercially available and used within their cleared indications.

Randomization

The study was planned to include at least 160 implants, corresponding approximately to 24 patients per centre. A block-randomization list with block sizes of 4 and 6 was generated by an independent person. This allowed a competitive recruitment of patients. Investigators received a sealed treatment envelop for each patient corresponding to either PS or PM group. Patients who met inclusion criteria after implant placement were randomized. If a patient could be randomized for both quadrants, it respected the following priorities: quadrant where the higher number of implants was required was first randomized; if both quadrants had the same number of implants priority was given to quadrant 4.

Pre-treatment and surgical procedures

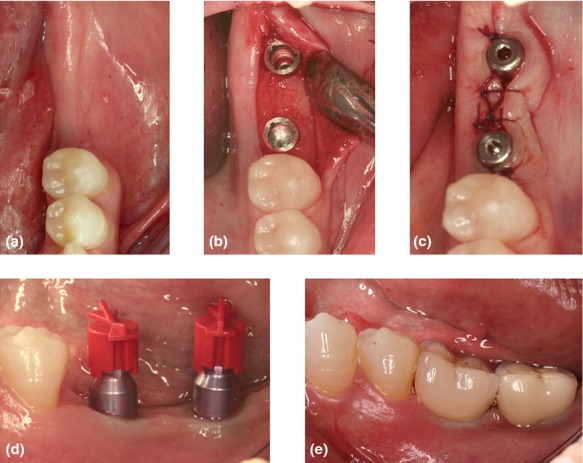

A calibration meeting preceded the study initiation. After eligibility the patients received oral hygiene instructions and intra-oral photographs were obtained. (Fig.1a) Prophylactic antibiotics were allowed according to the procedures of each centre. Surgery was performed in an outpatient facility under local anaesthesia. Implants were placed 0.4 mm supracrestally. (Fig.1b) The most proximal implant was placed 1.5–2.0 mm from the adjacent natural tooth and a minimal distance of 3.0 mm between two implants was left depending on the required space of the prosthetic crown. Primary stability was assessed using direct hand testing. The healing abutment (PS or PM) was selected according to the randomization and fitted immediately after surgery. Healing was transgingival. Radiographs and photographs were taken immediately post-surgery. Patients were instructed to use a surgical brush in the site and to rinse three times per day with chlorhexidine (0.12%) until sutures were removed (Fig.1c).

Fig 1.

(a) Pre-operative view of the edentulous area. (b) The implants placed 0.4 mm supracrestal. (c) The healing abutments were inserted according to the randomization and the flap was sutured. (d) Impression copings. (e) Single ceramo-metal crowns were cemented.

Prosthesis placement

For implants inserted in bone type I–III, impression (PS or PM) was planned to be taken at least 6 weeks post-surgery and in bone type IV at 12 weeks. Final abutments were torqued to 20 Ncm and crowns were cemented 2–3 weeks later. The day of prosthesis placement was the baseline for further measurements (Fig.1d,e).

Primary and secondary objectives

The primary objective was to determine the level at which the bone can be predictably maintained in relation to the implant shoulder when the implants were restored either with PS or PM abutments.

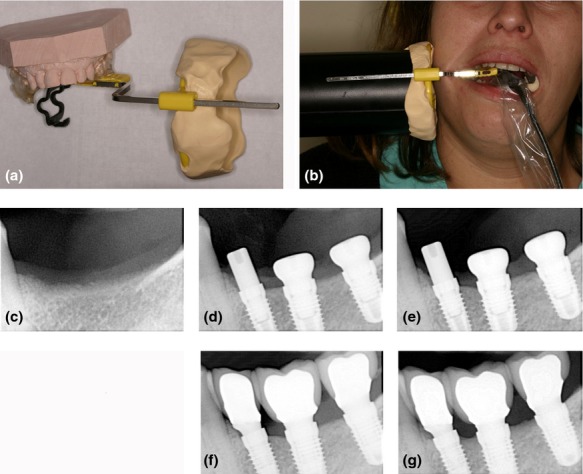

Bone level changes were evaluated on standardized peri-apical radiographs, which were taken using a customized holder at pre-surgery, immediately post-surgery with healing abutment, at loading and at 12 months following baseline with further evaluations planned at 24, 36, 48 and 60 months post-loading (Fig.2). Two centres used digital radiography and one centre digitized their analogue radiographs by scanning. The distance from the mesial and distal first visible bone contact to the implant shoulder was measured to the nearest 0.1 mm and the mean of the two measurements was calculated. The radiographical measurements were validated and analysed by an independent person using ImageJ 1.44p (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Fig 2.

(a, b) Peri-apical radiographs were standardized using a customized holder (c) Standardized peri-apical radiographs were taken before implant placement (c), immediately post-surgery (d), before (e) and after abutment/crown placement (f) and at 1 year post-loading (g).

The secondary objectives included implant success and survival rate at 1 year post-loading, performance of the restorative components, nature and frequency of the adverse events.

At each control visit the performance of the restoration and any occurrence of adverse events were recorded.

A particular implant was deemed a success or failure based on an assessment of implant mobility, peri-implant radiolucency, peri-implant recurrent infection and pain (Buser et al. 2002). A crown was deemed successful if it continued to be stable, functional, and if there was no associated patient discomfort.

Plaque index (PLI: 0–3), sulcus bleeding index (SBI: 0–3) and probing pocket depth (PPD) were measured at four sites per implant at loading, 6-month and 1-year post loading.

Statistical methods

The study was designed to test for equivalence of crestal bone levels of the groups receiving PM or PS rehabilitations. In order to achieve 80% power at a significance level of 0.01, sample size was computed considering similar distributions with 0.3 mm standard deviation (SD; Fischer & Stenberg 2004) in each group and minimum difference of 0.2 mm. PASS 2008 version 0.8.0.4 (NCSS, LCC, Kaysville, UT, USA) determined that 64 implants were required per treatment arm, corresponding to 24 (16–32) patients per group for randomization according to protocol. This RCT had 5 years of follow-up including multiple analysis thus the level of significance of the power analysis was adjusted to 0.01. Considering that the present paper reported only the 1-year results, an effective significance level of 0.05 was used.

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS® Statistics 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Demographics and baseline characteristics were descriptively reported. For continuous variables, means, standard deviations (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each treatment group, and numbers and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Bone level changes (BLC) were measured at mesial and distal implant site and averaged to represent the BLC over time per implant. The BLC were compared with two-way anova considering both randomization and centre effect at a significance level of 0.05. When no centre effect was determined, a two-sided t-test was used. Survival analysis was applied to calculate implant success and survival rate. Post-hoc multiple comparisons were performed using Bonferroni correction.

Results

Subjects and implants

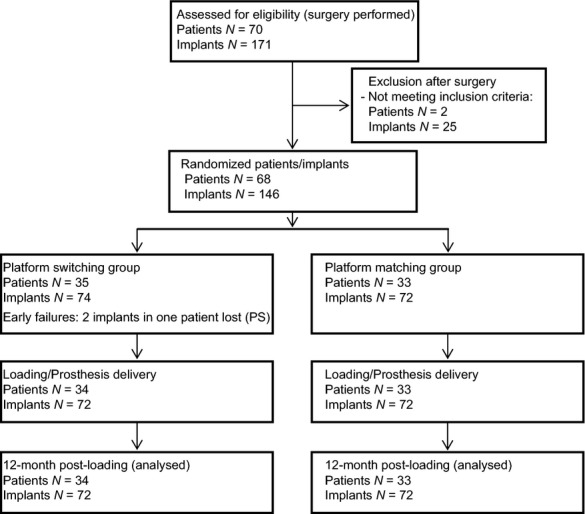

The current status of the study after 1 year of follow-up is illustrated in Fig.3. Between May 2009 and November 2011, a total of 68 patients, 37 male and 31 female were included. Thirty-five patients were randomized in the PS and 33 in the PM group. General health condition was assessed with the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system (ASA). Sixty one patients were classified as ASA 1 (89.7%) and seven patients as ASA 2 (10.3%). Oral hygiene at surgery was considered excellent (1.5%), good (80.9%) and fair (17.6%) and was homogeneously distributed between the two groups. The mean age of patients was 52.84 ± 10.38 in the PS and 49.97 ± 14.77 in the PM group (Table1a). A total of 146 implants were placed, 74 in the PS and 72 in the PM group. Sixty-one implants (41.8%) were 3.8 mm in diameter, 62 (42.5%) were 4.3 mm and 23 (15.8%) were 5.0 mm wide. Their distribution in the two groups by randomization was almost even. Seventy-six (52.1%) of the implants placed were 11 mm in length, 36 in the PS and 40 in the PM group. Forty-nine implants (33.6%) were 9 mm in length and 27 were placed in the PS and 22 in the PM group. Of the remaining 21 implants (14.4%) with 13 mm length 11 were placed in the PS and 10 in the PM group (Table1b). The position of implants by randomization is shown in Fig.4.

Fig 3.

Flow chart of the study design.

Table 1.

(a) Demographical and clinical parameter of the study population and the implanted sites. (b) Implant distribution for PS and PM according to length and diameter in mm. 41.8% of the implants were of Ø 3.8 mm, 42.5% of Ø 4.3 mm

| (a) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | PS | PM |

| Characteristics (patients) | 35 | 33 |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 52.84 ± 10.38 | 49.97 ± 14.77 |

| Gender male/female | 18/17 | 19/14 |

| Implants per quadrant | ||

| 2 adjacent implants | 31 | 27 |

| 3 adjacent implants | 4 | 6 |

| Implants (n) | 74 | 72 |

| Centre 1 | 12 | 12 |

| Centre 2 | 25 | 22 |

| Centre 3 | 37 | 38 |

| Bone quality; n implants (%) | ||

| Class I | 4 (5.4) | 4 (5.6) |

| Class II | 40 (54.1) | 45 (62.5) |

| Class III | 26 (35.1) | 22 (30.6) |

| Class IV | 4 (5.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Torque at insertion; n implants | 37 | 36 |

| Mean ± SD (Ncm) | 31.95 ± 4.39 | 31.25 ± 3.02 |

| Min/Max | 25/45 | 25/35 |

| (b) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter /Length | PS | PM | ||||

| Ø 3.8 | Ø 4.3 | Ø 5.0 | Ø 3.8 | Ø 4.3 | Ø 5.0 | |

| 9 mm | 11 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 3 |

| 11 mm | 15 | 17 | 4 | 16 | 19 | 5 |

| 13 mm | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 30 | 30 | 14 | 31 | 32 | 9 |

PM, platform matching; PS, platform switching.

No significant differences between study groups were observed (Mann Whitney rank test, Chi square test).

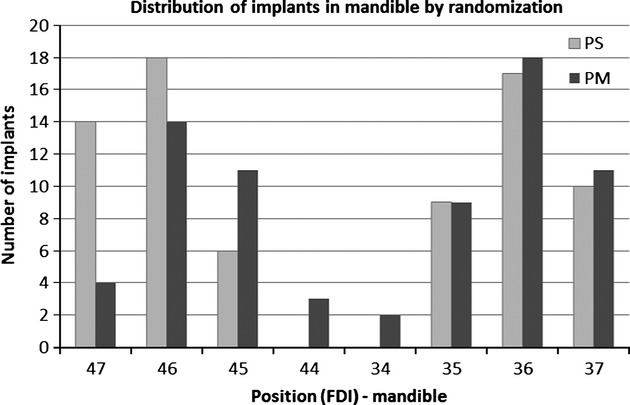

Fig 4.

Distribution of implants in posterior mandible according to randomization (platform switching = 74, platform matching = 72).

Within the PS group 31 sites (88.6%) received two and four (11.4%) received three implants. The PM group represented 27 sites (81.8%) with two and six (18.2%) with three implants.

In both groups the majority of implants were placed in type II or type III bone classified according to Lekholm & Zarb (1985) (Table1a).

All implants were firmly anchored and free of mobility at insertion. Measurement of the torque value was optional and thus measured for 73 implants (37 in the PS and 36 in the PM group). Values ranged from 25 to 45 Ncm. After a mean healing period of 8.56 ± 4.21 weeks in the PS and 8.11 ± 5.21 weeks in the PM group, impression was taken. Implants were restored with single crowns 12.33 ± 5.27 weeks post-surgery in the PS and 12.14 ± 6.02 weeks in the PM group. No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups. The type of cemented crowns was 81.9% of metal-ceramic for the PS and 85.1% for the PM group and 18.1% and 14.9% ceramo-ceramic, respectively.

Implant success and complications

During the healing period two implants were lost (pre-loading failures) in the PS group, and none in the PM group, thereafter no complications according to Buser et al. (2002) were observed yielding to implant success rates of 97.3% and 100%, respectively. One patient experienced an extensive ceramic chipping at 12 months post-loading visit and required new impression and prosthesis delivery.

Plaque index, sulcus bleeding index and probing depth over time

Plaque and sulcus bleeding index were determined in mean values. Probing pocket depth (PPD) was measured in mm and reported in mean values (Table2a). No statistical significance was noticed between the two groups at loading, 6 and 12 months post-loading.

Table 2.

(a) Soft-tissue health: PI, SBI, PPD. (b) Mean crestal bone level changes in mm

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | PM | |||

| N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | |

| Plaque index (Score 0–3) | ||||

| Loading | 68 | 0.25 ± 0.46 | 69 | 0.06 ± 0.18 |

| 6-months | 67 | 0.13 ± 0.22 | 67 | 0.06 ± 0.14 |

| 12-months | 72 | 0.10 ± 0.21 | 70 | 0.09 ± 0.18 |

| Sulcus bleeding index (Score 0–3) | ||||

| Loading | 68 | 0.05 ± 0.12 | 69 | 0.01 ± 0.06 |

| 6-months | 67 | 0.22 ± 0.28 | 67 | 0.20 ± 0.32 |

| 12-months | 72 | 0.21 ± 0.28 | 70 | 0.20 ± 0.29 |

| Probing pocket depth in mm | ||||

| Loading | 64 | 1.78 ± 0.79 | 61 | 1.69 ± 0.51 |

| 6-months | 62 | 2.18 ± 0.51 | 62 | 2.48 ± 0.59 |

| 12-months | 72 | 2.21 ± 0.47 | 70 | 2.46 ± 0.51 |

| (b) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | PM | p-value | |||

| N | Mean ± SD (mm) | N | Mean ± SD (mm) | ||

| Surgery to loading | 70 | −0.50 ± 0.42 | 63 | −0.66 ± 0.70 | Ns |

| Loading to 12-month | 70 | 0.08 ± 0.41 | 61 | −0.06 ± 0.49 | Ns |

| Surgery to 12-month | 72 | −0.40 ± 0.46 | 70 | −0.69 ± 0.68 | 0.004* |

ns, non-significant; PM, platform matching; PS, platform switching; PI, plaque index; PPD, probing pocket depth; SBI, sulcus bleeding index.

No significant differences between study groups were observed.

Difference between study groups is statistically significant (independent student's t-test).

Radiographical changes in crestal bone levels

Out of the 144 study implants, standard radiographs were available for 142 implants from surgery to 12 months (72 PS and 70 PM) and for 131 implants from loading to 12 months (70 PS and 61 PM). For 13 implants radiographs were not taken either at loading (11 implants) or at 12 months (two implants).

The total mean BLC (a positive value represents a bone gain, and a negative a bone loss) from surgery to 12 months was −0.54 ± 0.59 mm (95% CI: −0.64, −0.44). Two-way anova determined no interaction between the centre and the treatment group on BLC (p = 0.762) and no centre effect was determined (p = 0.533). From surgery the mean BLC in the PS group was −0.40 ± 0.46 mm (95% CI: −0.51, −0.29) and −0.69 ± 0.68 mm (95% CI: −0.85, −0.53) in the PM group with significance (p = 0.004).

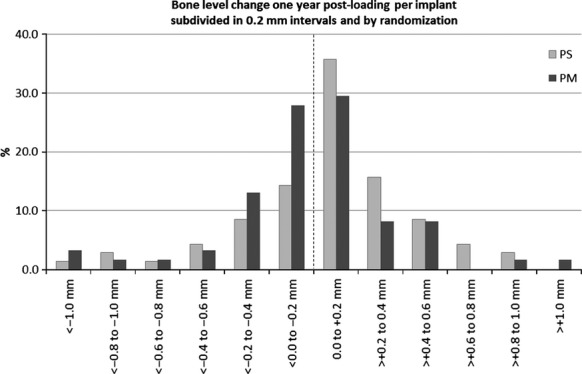

From loading to 12 months the total mean BLC was 0.01 ± 0.45 mm (95% CI: −0.06, 0.09). The analysis from loading revealed a statistically significant interaction between the centre and the treatment group on BLC (p = 0.018). The mean BLC in the PS group was 0.08 ± 0.41 mm (95% CI: −0.02, 0.18) and −0.06 ± 0.49 mm (95% CI: −0.18, 0.07) in the PM group. Pairwise comparisons for each centre determined a significant mean difference of 0.30 between PS and PM in one centre (p = 0.003; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.56). The other two centers showed no significant differences. Radiographical bone gain from loading to 12 months was observable in 67.1% of the PS and in 49.2% of the PM implants. The results are summarized in Table2b and Fig.5.

Fig 5.

Mean bone level changes at 1-year post-loading. Number of implants subdivided in 0.2 mm intervals. In 67.1% of the implants in platform switching group and 49.2% in platform matching group bone gain was observed.

Discussion

In this RCT some study design factors must be taken into consideration: to the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first RCT where commercially available implants with identical outer geometry and internal implant-abutment connection for both groups were used allowing comparable conditions. These factors may contribute to a more accurate and better understanding of how PS can influence marginal bone levels around implants with the same features.

Randomization was done after surgery regarding to avoid any tendency to change surgical protocol. This aspect is important to exclude any bias regarding implantation depth, which revealed to be of influence on marginal bone levels (Nicolau et al. 2013).

The present study yields a mean marginal bone level value change from surgery to 12 months post-loading of −0.40 ± 0.46 mm for PS and −0.69 ± 0.58 mm for PM, showing a significant difference (p = 0.004). Our findings are comparable with those of Canullo et al. (2010a) who reported a higher bone loss in the PM group than in the PS one. However, their design included several dimensions of mismatch from 0.25 mm to 0.85 mm. They postulated that the BLC could be biased by the fact the mismatch was done by increasing the diameter of the implants and then not necessarily reflecting the real situation. Our study reflected a patient-oriented approach of the real situation since the diameter of the implant was selected according to the available buccal-lingual bone width and the maximum mismatch was 0.35 mm for the 5.0 mm implants.

Enkling et al. (2011) using implants with a similar mismatch (0.35 mm) in the posterior mandible could not find a statistical difference between groups. Baseline was at surgery, however, implants healed in a submerged position. This means that the first 3 months of bone remodeling could not be influenced by different healing abutments as occurred in our study. Also the fact that both implants were randomized next to each other on the same side of the mandible could influence marginal bone resorption, this was not the case in our observations. In fact, in our study the influence of a platform healing abutment seemed to benefit bone preservation in favour of the platform switching group.

From prosthetic placement to 1 year post-loading, one centre presented a significant difference (p = 0.003) in mean BLC between groups, however, the overall results did not confirm this finding. One of the explanations to this centre effect could be the result of patient distribution among centres (Table1a). Hürzeler et al. (2007) in a single centre study reported a significant mean BLC from final prosthetic reconstruction to 1-year follow-up of −0.12 ± 0.40 mm for PS group and −0.29 ±0.34 mm for the PM group (p = 0.0132).

Changes were noticed in crestal bone levels after surgery and before loading between groups but not significant and the limited amount of crestal bone loss is according to a theoretical biological response to device installation as reported by Raghavendra et al. (2005). Indeed, our flat-to-flat abutment connection model using platform switching concept from the day of surgery (PS healing abutments, PS impression posts) could have an influence in early crestal bone remodeling. This could be an additional factor in the biological process taking place before prosthetic restoration and not only after as suggested by some authors (Hermann et al. 2007). Emphasizing the biological aspect it seems that bone resorption may be related to the re-establishment of biological width that takes place following bacterial invasion of the implant/abutment interface (Canullo et al. 2012). Indeed, in our study significant differences were found from surgery to 12-month post-loading suggesting that changes could happen in a time-dependent manner.

Some systematic reviews and meta-analysis suggested an implant/abutment mismatch of at least 0.4 mm is more beneficial for preserving marginal bone (Atieh et al. 2010, and Annibali et al. 2012). In our study, even with mismatches of 0.3 mm and 0.35 mm we could observe a difference between PS and PM. Radiographical bone gain or no changes at 12 months post-loading was noted in 67.1% for the platform switching implants, meaning 47 out of 70 implants, and 49.2% for the standard group, meaning 30 implants out of 61.

Of the 146 implants placed, 2 were lost due to pre-loading failure in the PS group, yielding implant success rates of 97.3% in PS and 100% in PM. Within the secondary outcome (PI, SBI, PD) we could not identify statistical differences between the two groups.

We hypothesized that there is no difference at PS and PM 1-year post-loading. We found a statistically significant difference in terms of BLC between the two groups between surgery and 12 months post-loading and no significant difference between loading and 12 months. Therefore we were unable to reject the hypothesis. In spite of that, for each time interval the mean bone loss and variance were lower for the PS group. We could demonstrate that PS reduced peri-implant crestal bone resorption at 1-year post-loading. These results are in accordance with previous clinical studies (Cappiello et al. 2008, Fernández-Formoso et al. 2012, Telleman et al. 2012). This is a 5-year ongoing clinical study and further results are necessary to determine if the concept of PS will show superiority in terms of BLC over time, as suggested by other authors (Astrand et al. 2004, Vigolo & Givani 2009).

Limitations of the present results are related mostly to the ongoing status of the study but the relevant results up to this moment justify dissemination and may help clinicians, in our opinion, to decide in a more accurate perspective and a better understanding on procedures and choices between PS and PM abutments within the same implant system.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of the present study platform switching showed a positive impact in maintenance or even enhancement of crestal bone levels when compared with platform matching abutments of the same implant system, allowing clinicians to a better understanding of two different techniques at 12 months post-loading.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Françoise Peters, Alex Schär and Peter Thommen from the Camlog Foundation for their organizational support and also to Ana Messias for her contribution in the statistical analysis.

Biography

Clinical Relevance.

Scientific rationale for the study: Platform switching aims to preserve crestal bone height and soft tissue levels increasing quality outcomes. However, there's a lack of prospective randomized clinical trials evaluating platform switching versus platform matching with identical implant outer geometry and same internal implant-abutment connection allowing comparable results.

Principal findings: Platform switching group showed significant interproximal bone preservation or even bone gain between the time of surgery and 12-month post-loading compared to the platform matching group.

Practical implications: Platform switching preserves the marginal bone level more predictably than the implants restored with matching abutments in the posterior mandible after 1 year post-loading.

References

- Al-Nsour MM, Chan H. Wang H. Effect of the platform-switching technique on preservation of peri-implant marginal bone: a systematic review. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2012;27:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annibali S, Bignozzi I, Cristalli MP, Graziani F, La Monaca G. Polimeni A. Peri-implant marginal bone level: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing platform switching versus conventionally restored implants. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2012;39:1097–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrand P, Engquist B, Dahlgren S, Gröndahl K, Engquist E. Feldmann H. Astra Tech and Branemark system implants: a 5-year prospective study of marginal bone reaction. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2004;15:413–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atieh MA, Ibrahim HM. Atieh AH. Platform switching for marginal bone preservation around dental implants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Periodontology. 2010;81:1350–1366. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Ferrari D, Herten M, Kirsch A, Schaer A. Schwarz F. Influence of platform switching on crestal bone changes at non-submerged titanium implants: a histomorphometrical study in dogs. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2007;34:1089–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Ferrari D, Mihatovic I, Sahm N, Schaer A. Schwarz F. Stability of crestal bone level at platform switched non-submerged titanium implants: a histomorphometrical study in dogs. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2009;36:532–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser D, Ingmarsson S, Dula K, Lussi A, Hirt HP. Belser UC. Long-term stability of osseointegrated implants in augmented bone: a 5-year prospective study in partially edentulous patients. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2002;22:108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canullo L, Fedele GR, Iannello G. Jepsen S. Platform switching and marginal bone-level alterations: the results of a randomized-controlled trial. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2010a;21:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canullo L, Goglia G, Iurlaro G. Iannello G. Short-term bone level observations associated with platform switching in immediately placed and restored single maxillary implants: a preliminary report. The International Journal of Prosthodontics. 2009;22:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canullo L, Iannello G, Peñarocha M. Garcia B. Impact of implant diameter on bone level changes around platform switched implants: preliminary results of 18 months follow-up a prospective randomized match-paired controlled trial. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2012;23:1142–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canullo L, Pellegrini G, Allievi C, Trombelli L, Annibali S. Dellavia C. Soft tissues around long-term platform switching implant restorations: a histological human evaluation. Preliminary results. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2011;38:86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canullo L, Quaranta A. Teles RP. The microbiota associated with implants restored with platform switching: a preliminary report. Journal of Periodontology. 2010b;81:403–411. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappiello M, Luongo R, Di Iorio D, Bugea C, Cocchetto R. Celletti R. Evaluation of peri-implant bone loss around platform-switched implants. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2008;28:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CL, Chen CS. Hsu ML. Biomechanical effect of platform switching in implant dentistry: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2010;25:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchetto R, Traini T, Caddeo F. Celletti R. Evaluation of hard tissue response around wider platform switched implants. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2010;30:163–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran DL, Bosshardt DD, Grize L, Higgenbotton FL, Jones AA, Jung RE, Wieland M. Dard M. Bone response to loaded implants with non-matching implant-abutment diameters in the canine mandible. Journal of Periodontology. 2009;80:609–617. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi R, Capparè P. Gherlone E. Radiographic evaluation of marginal bone levels around platform-switched and non–platform-switched implants used in an immediate loading protocol. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2009;24:920–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degidi M, Iezzi G, Scarano A. Piattelli A. Immediately loaded titanium implant with a tissue-stabilizing/maintaining design (“beyond platform switch”) retrieved from man after 4 weeks: a histological and histomorphometrical evaluation. A case report. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2008;19:276–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkling N, Johren P, Klimberg V, Bayer S, Mericske-Stern R. Jepsen S. Effect of platform switching on peri-implant bone levels: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2011;22:1185–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Formoso N, Rilo B, Mora MJ, Martínez-Silva I. Díaz-Afonso AM. Radiographic evaluation of marginal bone maintenance around tissue level implant and bone level implant: a randomised controlled trial. A 1-year follow-up. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2012;39:830–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2012.02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickl S, Zuhr O, Stein JM. Hurzeler MB. Peri-implant bone level around implants with platform-switched abutments. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2010;25:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K. Stenberg T. Early loading of ITI implants supporting a maxillary full-arch prosthesis: 1-year data of a prospective, randomized study. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2004;19:374–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann F, Lerner H. Palti A. Factors influencing the preservation of the periimplant marginal bone. Implant Dentistry. 2007;16:165–175. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e318065aa81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hürzeler M, Fickl S, Zuhr O. Wachtel HC. Peri-implant bone level around implants with platform-switched abutments: preliminary data from a prospective study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;65(suppl 1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung RE, Jones AA, Higginbottom FL, Wilson TG, Schoolfield J, Buser D, Hämmerle CH. Cochran D. The influence of non-matching implant and abutment diameters on radiographic crestal bone levels in dogs. Journal of Periodontology. 2008;79:260–270. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kielbassa AM, Martinez-de Fuentes R, Goldstein M, Arnhart C, Barlattani A, Jackowski J, Knauf M, Lorenzoni M, Maiorana C, Mericske-Stern R, Rompen E. Sanz M. Randomized controlled trial comparing a variable-thread novel tapered and a standard tapered implant: interim one year results. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 2009;101:293–305. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara RJ. Porter SS. Platform switching: a new concept in implant dentistry for controlling postrestorative crestal bone levels. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2006;26:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekholm U. Zarb GA, Branemark PI, Zarb GA. Patient selection and preparation. In: Albrektsson T, editor; Tissue Integrated Prostheses: Osseointegration in Clinical Dentistry. Chicago, IL: Quintessence; 1985. pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Luongo R, Traini T, Guidone PC, Bianco G, Cocchetto R. Celletti R. Hard and soft tissue responses to the platform-switching technique. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2008;28:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Miura J, Taki I. Sogo M. Biomechanical analysis on platform switching: is there any biomechanical rationale? Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2007;18:581–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolau P, Korostoff J, Ganeles J, Jackowski J, Krafft T, Neves M, Divi J, Rasse M, Guerra F. Fischer K. Immediate and early loading of chemically modified implants in posterior jaws: 3-year results from a prospective randomized multicenter study. Clinical Implant Dentistry and Related Research. 2013;15:600–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh TJ, Yoon J, Misch CE. Wang HL. The causes of early implant bone loss: Myth or science? Journal of Periodontology. 2002;73:322–333. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosper L, Redaelli S, Pasi M, Zarone F, Radaelli G. Gherlone EF. A randomized prospective multicenter trial evaluating the platform-switching technique for the prevention of postrestorative crestal bone loss. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2009;24:299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra S, Wood MC. Taylor TD. Early wound healing around endisseous implants: a review of literature. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2005;20:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrotenboer J, Tsao YP, Kinariwala V. Wang HL. Effect of platform switching on implant crest bone stress: a finite element analysis. Implant Dentistry. 2009;18:260–269. doi: 10.1097/ID.0b013e31819e8c1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Sánchez P, Calvo-Guirado JL, Manzanera-Pastor E, Lorrio-Castro C, Bretones-López P. Pérez-Llanes JA. The influence of platform switching in dental implants. A literature review. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2011;16:e400–e405. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telleman G, Raghoebar GM, Vissink A. Meijer HJ. Impact of platform switching on inter-proximal bone levels around short implants in the posterior region; 1-year results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2012;39:688–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trammell K, Geurs NC, O'Neal SJ, Liu PG, Kenealy JN. Reddy MS. A prospective, randomized, controlled comparison of platform-switched and matched-abutment implants in short-span partial denture situations. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry. 2009;29:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigolo P. Givani A. Platform-switched restorations on wide diameter implants: a 5-year clinical prospective study. The International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2009;24:103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]