Abstract

Purpose

A prospective, epidemiologic study was conducted to assess whether the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccination in Germany almost exclusively using an AS03-adjuvanted vaccine (Pandemrix) impacts the risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) and its variant Fisher syndrome (FS).

Methods

Potential cases of GBS/FS were reported by 351 participating hospitals throughout Germany. The self-controlled case series methodology was applied to all GBS/FS cases fulfilling the Brighton Collaboration (BC) case definition (levels 1–3 of diagnostic certainty) with symptom onset between 1 November 2009 and 30 September 2010 reported until end of December 2010.

Results

Out of 676 GBS/FS reports, in 30 cases, GBS/FS (BC levels 1–3) occurred within 150 days following influenza A(H1N1) vaccination. The relative incidence of GBS/FS within the primary risk period (days 5–42 post-vaccination) compared with the control period (days 43–150 post-vaccination) was 4.65 (95%CI [2.17, 9.98]). Similar results were found when stratifying for infections within 3 weeks prior to onset of GBS/FS and when excluding cases with additional seasonal influenza vaccination. The overall result of temporally adjusted analyses supported the primary finding of an increased relative incidence of GBS/FS following influenza A(H1N1) vaccination.

Conclusions

The results indicate an increased risk of GBS/FS in temporal association with pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccination in Germany. © 2014 The Authors. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: Guillain–Barré syndrome, pandemic influenza vaccination, self-controlled case series, pharmacoepidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) is an acute, immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy.1 Typically, it is clinically characterized by bilateral limb paresis and hyporeflexia/areflexia. Fisher syndrome (FS) is considered as a rare variant of GBS presenting with ataxia, ophthalmoplegia, and areflexia. The overall GBS incidence was estimated to be between 1.1 and 1.8/100 000/year.2,3 GBS is deemed to be an autoimmune disease.1,4 Frequently, GBS is preceded by a gastrointestinal or respiratory infection. Antecedent pathogens include Campylobacter jejuni, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, or varicella zoster virus.4 Some recent studies and reports suggest that influenza virus infection may also act as a relevant trigger for GBS.5–9

In 1976, a US vaccination campaign against swine influenza had to be stopped prematurely because of an increased number of GBS reports following immunization. Several studies10–12 found a temporal association between the 1976 swine influenza vaccines and GBS. Subsequent studies on seasonal influenza vaccines5,12 found no13–17 or only a slightly elevated risk of GBS after immunization.18,19 The increased risk of GBS after the 1976 swine influenza vaccination raised concerns that the pandemic swine influenza vaccines of 2009 might also be associated with GBS. Therefore, a prospective study was conducted by the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut (PEI), the German national competent authority, to evaluate whether there was a temporal association between the 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccination and GBS/FS.

METHODS

In Germany, the influenza A(H1N1) vaccination campaign started on 26 October 2009, almost exclusively using an inactivated, monovalent, AS03-adjuvanted vaccine (Pandemrix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium). A self-controlled case series (SCCS) design was applied.20–23 The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hessian Medical Association in Frankfurt, Germany. The study period ran from 1 November 2009 to 30 September 2010. A(H1N1) vaccination had practically stopped by the end of December 2009 in Germany with only a few vaccinations at the beginning of 2010.24

Participating hospitals

Initially, 316 neurologic and 346 pediatric acute hospitals in Germany were asked to participate in the study. A total of 351 hospitals (227 neurologic and 124 pediatric hospitals) participated in the study. In each hospital, a physician was nominated as a contact person. The hospitals were asked to report all GBS/FS cases occurring during the study period, regardless of whether any influenza vaccine had been administered or not. In addition, the PEI requested each participating hospital on a regular basis to declare whether a case of GBS/FS had occurred in the meantime.

Case ascertainment

Guillain–Barré syndrome/FS cases were documented on a pseudonymized and standardized reporting form. The following information was collected: year of birth; sex; region of residence; date of symptom onset; clinical details required for classification according to the Brighton Collaboration (BC) case definition25; therapy; outcome; gastrointestinal, respiratory, or other infections within 3 weeks prior to symptom onset; pathogen proof concerning preceding infection; immunization status regarding A(H1N1) vaccination and seasonal influenza vaccination including vaccination date, vaccine brand, batch number, and dose (first or second). Hospitals had to verify the immunization status by reviewing the vaccination certificate or contacting the vaccinating physician/general practitioner. Missing essential information was queried by PEI.

Reports were included in the study only if the subjects were residents of Germany. All reports of a GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination or seasonal influenza vaccination were independently assessed against the BC case definition of GBS/FS by a neurologist from PEI (J. P.) and by an external neurologist (H. C. L.), who was blinded to the immunization status of cases. Reported events that met the case definition were classified into level 1, 2, or 3 of diagnostic certainty. If the evidence available for an event was insufficient to permit classification at any level of diagnostic certainty, it was categorized as level 4. Level 5 reflects the exclusion of GBS/FS according to the case definition.

For the statistical analysis, a case was defined as GBS or FS according to the BC case definition (levels 1–3) within 150 days following A(H1N1) vaccination or seasonal influenza vaccination. Cases were included in the analysis only if the date of the first A(H1N1) vaccination (or seasonal influenza vaccination) and the date of GBS/FS onset fell into the study period.

Statistical analysis

Relative incidence (RI) estimates for GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination/seasonal influenza vaccination were calculated by means of conditional Poisson regression. The null hypothesis of no increased RI of GBS/FS in a predefined risk period compared with a control period was tested. To account for an interim analysis, a critical p-value of 0.046 was applied in the final analysis, and 95%CIs were calculated using the repeated confidence interval approach.26 Unvaccinated GBS/FS cases contributed to the estimation of temporal effects. For the primary analysis, the risk period was defined as days 5–42 after vaccination and the control period as days 43–150 after vaccination (day 1 refers to the day of vaccination). The risk period chosen for the primary analysis extends to day 42 after vaccination because the period of increased risk of GBS after the 1976 swine influenza vaccination campaign was concentrated primarily within 6 weeks following vaccination.11 Additional analyses were performed, assessing the impact of different definitions of risk and control periods as well as the impact that possible confounders (e.g., age, sex, and previous infections) might have on the RI of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination. In order to control for confounding by contraindication to A(H1N1) vaccination, pre-vaccination time intervals were not included in the control periods.27,28

Statistical analyses were performed using the sas software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Control for confounding

In Germany, the A(H1N1) vaccination period24 and the pandemic peak period29 were roughly identical (i.e., November 2009–January 2010). Adjusted analyses were performed post hoc in an attempt to account for possible seasonal effects on the risk of GBS/FS.20,27 An adjustment for calendar months and an adjustment for A(H1N1) influenza season (November 2009–January 2010 and February–September 2010) were conducted. The temporal adjustment was performed for the primary analysis population of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases as well as for an “enriched population” combining information from the primary population and unvaccinated subjects with GBS/FS onset (BC levels 1–3) during the study period. Unvaccinated subjects were included in the “enriched population” with no risk period and a control period identical to the study period.

To investigate possible selective reporting of GBS/FS cases, the hospitals were asked retrospectively to provide the total number of cases with International Classification of Diseases (ICD) discharge diagnosis GBS/FS (according to their ICD hospital database), which occurred during the study period, and the month of hospital admission in each case. The number of GBS/FS study reports was compared with the number of cases with ICD discharge diagnosis GBS/FS for each hospital that participated in both the study and the additional survey. SCCS analyses were performed, restricted to A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases from hospitals that participated in the additional survey with comparable number of reports in the study and survey.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

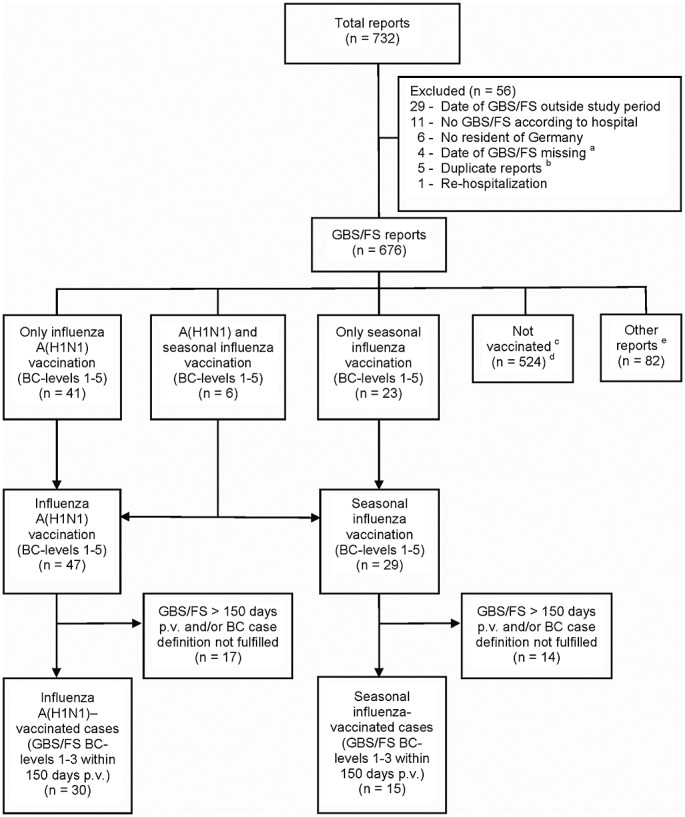

A total of 732 reports were transmitted to PEI. Fifty-six of these reports were excluded (Figure 1). As diagnosed by the reporting physicians, 617/676 reports (91.3%) referred to GBS, 54/676 reports (8.0%) referred to FS, and in 5/676 reports (0.7%), both GBS and FS were diagnosed. Four hundred eighty-six of these 676 reports fulfilled the BC case definition (levels 1–3). In 30 cases, a GBS/FS (levels 1–3) occurred within 150 days following A(H1N1) vaccination (all Pandemrix), and 15 patients developed GBS/FS (levels 1–3) within 150 days following vaccination against 2009/2010 seasonal influenza (Table 1). Ten of the 19 GBS/FS cases that occurred within 42 days after A(H1N1) vaccination occurred during days 6–10 (median 9 days). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the different patient populations are shown in Table 2. In 36.7% of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases—in contrast to reports without vaccination (50.0%)—a preceding gastrointestinal and/or respiratory infection was reported within 3 weeks prior to the first GBS/FS symptoms (not significant, Fisher test). Proof of a bacterial or viral pathogen concerning an antecedent infection was reported in 6.7% of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases compared with 14.5% in reports without vaccination (not significant, Fisher test).

Figure 1.

Patient flow. aAmong four reports that were excluded from the study because of missing date of GBS/FS, one report referred to A(H1N1) vaccination. Including this report in a sensitivity SCCS analysis altered the result only marginally. bDuplicate reports: Five patients with onset of GBS/FS during the study period were reported twice, each by different participating hospitals. For these patients, the report from the initially treating hospital was included in the analysis. cThe “not vaccinated” population contains only reports without A(H1N1) vaccination and without seasonal influenza vaccination in the season 2009/2010. Reports with A(H1N1) and/or seasonal influenza vaccination in 2009/2010 prior to 1 November 2009 were included in the population of “other reports.” dOut of these, 362 reports fulfilled the BC case definition (levels 1–3). e“Other reports” include one report with A(H1N1) vaccination prior to 1 November 2009, 54 reports with seasonal influenza vaccination prior to 1 November 2009, one report with GBS onset before seasonal influenza vaccination, three reports with unknown month of seasonal influenza vaccination, 20 reports (3.0% of all 676 GBS/FS reports) with unknown vaccination status regarding A(H1N1) and seasonal influenza vaccination, and three reports with unknown vaccination status regarding seasonal influenza vaccination. BC, Brighton Collaboration; FS, Fisher syndrome; GBS, Guillain–Barré syndrome; p.v., post-vaccination

Table 1.

Time interval between vaccination with influenza A(H1N1) vaccine and/or seasonal influenza vaccines and first symptoms of GBS/FS

| Reports of influenza A(H1N1) vaccination | Reports of seasonal influenza vaccination | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of exposure | BC levels 1–5 | BC levels 1–3 | BC levels 1–5 | BC levels 1–3 |

| 1–4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | - |

| 5–21 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 5 |

| 22–42 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| 43–62 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 63–150 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| Total within 150 days p.v. | 37 | 30* | 20 | 15* |

| >150 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 |

BC, Brighton Collaboration; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; FS, Fisher syndrome; p.v., post-vaccination.

Out of these GBS/FS cases (BC levels 1–3), three patients received both influenza A(H1N1) vaccination and seasonal influenza vaccination during the study period within 150 days prior to the first symptoms of GBS/FS. None of these three patients were vaccinated with both vaccines on the same day.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| GBS/FS reports (n = 676) | Influenza A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases*(n = 30) | Seasonal influenza-vaccinated cases* (n = 15) | Not vaccinated (n = 524) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 302 (44.7) | 10 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 239 (45.6) |

| Male | 374 (55.3) | 20 (66.7) | 10 (66.7) | 285 (54.4) |

| Age | ||||

| Median (range) | 58.5 (1–90) | 62.0 (4–82) | 66.0 (14–88) | 56.0 (1–90) |

| <10 years, n (%) | 21 (3.1) | 1 (3.3) | — | 18 (3.4) |

| 10–60 years, n (%) | 344 (50.9) | 12 (40.0) | 4 (26.7) | 290 (55.3) |

| >60 years, n (%) | 311 (46.0) | 17 (56.7) | 11 (73.3) | 216 (41.3) |

| Patients with infections within 3 weeks prior to the first GBS/FS symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| GI | 175 (25.9) | 7 (23.3) | 1 (6.7) | 140 (26.7) |

| Respiratory | 173 (25.6) | 5 (16.7) | 4 (26.7) | 135 (25.8) |

| GI and/or respiratory | 333 (49.3) | 11 (36.7) | 5 (33.3) | 262 (50.0) |

| Others | 42 (6.2) | 2 (6.7) | — | 31 (5.9) |

| Any infection | 371 (54.9) | 13 (43.3) | 5 (33.3) | 290 (55.3) |

| Laboratory confirmation of pathogen (per patient), n (%) | ||||

| No | 463 (68.5) | 28 (93.3) | 11 (73.3) | 344 (65.6) |

| Yes | 101 (14.9) | 2 (6.7) | 4 (26.7) | 76 (14.5) |

| Missing | 112 (16.6) | — | — | 104 (19.8) |

| Confirmed pathogen† | ||||

| Campylobacter jejuni | 45 | 1 | 1 | 36 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 18 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| Epstein–Barr virus | 14 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Varicella zoster virus | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Haemophilus influenza | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 22 | 1 | 0 | 17 |

| BC levels 1–3, n (%) | 486 (71.9) | 30 (100) | 15 (100) | 362 (69.1) |

BC, Brighton Collaboration; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; FS, Fisher syndrome.

Within 150 days post-vaccination, BC levels 1–3.

Laboratory-confirmed pathogen regarding infections within 3 weeks prior to the first symptoms of GBS/FS; multiple entries possible.

Unadjusted self-controlled case series analyses

The unadjusted RI estimate for GBS/FS after A(H1N1) vaccination comparing the primary risk period (days 5–42 post-vaccination) with the control period (days 43–150 post-vaccination) was 4.65 (95%CI [2.17, 9.98]). An increased RI of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination was also seen when applying different definitions of risk and control periods (Table 3) and when stratifying for infections within 3 weeks prior to the first GBS/FS symptoms (Table 4). None of the other factors (age, sex, and BC level) was identified as an effect modifier (Table 4). The increased risk of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination was also seen when excluding cases with additional seasonal influenza vaccination (RI, 4.83; 95%CI [2.18, 10.7], regarding primary risk/control period) and in a further sensitivity analysis including level 4/level 5 reports, which may also reflect cases of (atypical) GBS/FS upon review by a neurologist (RI, 4.59; 95%CI [2.27, 9.28]).

Table 3.

Relative incidence of GBS/FS cases (BC levels 1–3) following influenza A(H1N1) vaccination: SCCS analyses

| Adjusted analysis restricted to A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases only | Adjusted analysis including information from unvaccinated subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted analysis | Monthly adjustment* | Adjustment for A(H1N1) season† | Monthly adjustment | Adjustment for A(H1N1) season† | |||

| Risk/control period (days p.v.) | Number of cases (risk/control) | RI [95%CI] | p-value | RI [95%CI] | RI [95%CI] | RI [95%CI] | RI [95%CI] |

| 5–42/43–150 | 18/11 | 4.65 [2.17, 9.98] | <0.001 | 1.12 [0.27, 4.64] | 2.96 [1.06, 8.25] | 5.35 [2.40, 11.9] | 4.56 [2.09, 9.96] |

| 1–42/43–150 | 19/11 | 4.44 [2.09, 9.46] | <0.001 | 1.19 [0.28, 5.01] | 2.85 [1.03, 7.90] | 5.13 [2.32, 11.3] | 4.36 [2.01, 9.44] |

| 5–42/1–4 and 43–150 | 18/12 | 4.42 [2.10, 9.30] | <0.001 | 1.67 [0.56, 4.95] | 2.80 [1.08, 7.26] | 5.03 [2.31, 11.0] | 4.33 [2.03, 9.25] |

| 1–42/43–84 | 19/6 | 3.17 [1.24, 8.06] | 0.014 | 0.95 [0.21, 4.36] | 2.71 [0.98, 7.54] | 3.32 [1.27, 8.71] | 3.16 [1.24, 8.05] |

| 1–58/59–150 | 21/9 | 3.70 [1.67, 8.20] | 0.001 | 0.45 [0.07, 2.93] | 1.92 [0.61, 6.06] | 4.27 [1.87, 9.79] | 3.62 [1.60, 8.17] |

BC, Brighton Collaboration; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; FS, Fisher syndrome; p.v., post-vaccination; RI, relative incidence; SCCS, self-controlled case series.

Not considered reliable owing to problems regarding identifiability: The likelihood ratio test rejected the global null hypothesis, but none of the model parameters (i.e., risk and months) was statistically significant. The parameter estimates for the monthly components had huge standard errors and were highly correlated.

A(H1N1) influenza season: time intervals, November 2009–January 2010 and February 2010–September 2010.

Table 4.

Influenza A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases (BC levels 1–3): unadjusted SCCS analyses stratified for age, sex, preceding infection, and BC level

| Factor | Influenza A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases in risk period (days 5–42) | Influenza A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases in control period (days 43–150) | Unadjusted RI [95%CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | |||

| <10 years | 1 | 0 | NA* |

| 10–60 years | 7 | 5 | 3.98 [1.24, 12.8] |

| >60 years | 10 | 6 | 4.74 [1.69, 13.3] |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 12 | 8 | 4.26 [1.72, 10.6] |

| Female | 6 | 3 | 5.68 [1.39, 23.3] |

| Any infection† | |||

| Yes | 8 | 5 | 4.55 [1.46, 14.2] |

| No | 10 | 6 | 4.74 [1.69, 13.3] |

| Gastrointestinal and/or respiratory infection† | |||

| Yes | 7 | 4 | 4.97 [1.42, 17.4] |

| No | 11 | 7 | 4.47 [1.70, 11.7] |

| Gastrointestinal infection† | |||

| Yes | 4 | 3 | 3.78 [0.83, 17.4] |

| No | 14 | 8 | 4.97 [2.05, 12.0] |

| Respiratory infection† | |||

| Yes | 4 | 1 | 11.4 [1.22, 106] |

| No | 14 | 10 | 3.98 [1.74, 9.09] |

| BC level‡ | |||

| BC level 1 | 7 | 4 | 3.55 [1.38, 9.15] |

| BC level 2 | 11 | 7 | 7.58 [1.96, 29.3] |

BC, Brighton Collaboration; NA, not applicable; RI, relative incidence; SCCS, self-controlled case series.

Not evaluable as there were no cases in the control period.

Within 3 weeks prior to onset of GBS/FS.

No influenza A(H1N1)-vaccinated case was classified in BC level 3.

Self-controlled case series analyses with temporal adjustment

The results of the temporally adjusted analyses depend on the periods accounted for as well as on the patient population considered for adjustment (Table 3). By restricting temporal adjustment to the primary population of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases, the adjustment for A(H1N1) season resulted in a less pronounced but still significantly increased RI of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination (adjusted RI, 2.96; 95%CI [1.06, 8.25]), whereas the adjustment for months did not indicate an increased RI (adjusted RI, 1.12; 95%CI [0.27, 4.64]). When level 1–3 GBS/FS reports in unvaccinated subjects were included in the analysis model for temporal effects (“enriched population”), the resulting estimates for the RI of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination were similar to the unadjusted effects estimate (RI, 5.35; 95%CI [2.40, 11.9] in case of monthly adjustment; RI, 4.56; 95%CI [2.09, 9.96] in case of adjustment for A(H1N1) season) (Table 3). When including all unvaccinated subjects with BC levels 1–4 in the analysis, only marginal changes for the adjusted estimates were observed (RI, 5.47; 95%CI [2.47, 12.1] in case of monthly adjustment; RI, 4.48; 95%CI [2.06, 9.74] in case of adjustment for A(H1N1) season).

Seasonal influenza vaccination

The SCCS analyses regarding seasonal influenza vaccination did not indicate a significantly increased risk of GBS/FS. The unadjusted RI was 1.89 (95%CI [0.66, 5.42]) for the primary risk and control period and did not substantially change when temporal adjustment was performed (RI adjusted for A(H1N1) season, 1.62; 95%CI [0.44, 5.89]).

Retrospective survey

One hundred eighteen of the 227 neurologic hospitals (52.0%) and 76 of the 124 pediatric hospitals (61.3%) participating in the study also participated in the additional survey. Unadjusted SCCS analyses restricted to A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases from hospitals that transmitted a comparable number of reports in study and survey also indicated an increased risk of GBS/FS following A(H1N1) vaccination: The RI was 5.68 (95%CI [1.91, 16.96]) when solely A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases from those hospitals were included where the number of study reports was either greater or at most one report less than the number of ICD-coded GBS/FS cases during the study period. When including solely A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases from those hospitals where the number of study reports was either greater than or equal to the number of ICD-coded cases, the RI was 4.97 (95%CI [1.42, 17.37]).

DISCUSSION

We performed a prospective SCCS study with a robust case ascertainment. The unadjusted SCCS analysis indicated an elevated risk of GBS/FS in close temporal relation to A(H1N1) vaccination in Germany. The increased risk was also seen in various unadjusted sensitivity analyses. Stratification by preceding gastrointestinal and/or respiratory infection did not alter the results.

In 2009/2010, the influenza A(H1N1) vaccination period24 and the pandemic peak period29 in Germany roughly overlapped. This impacts the separation of the vaccination effect from temporal effects on the occurrence of GBS/FS. To account for possible temporal effects, adjusted analyses were performed post hoc. Adjusting for months in the primary population of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases did not indicate an elevated RI. However, this analysis revealed severe problems regarding identifiability (which might be partly due to the time pattern of vaccination and GBS/FS cases and partly due to the restricted sample size), questioning the validity of the results of this specific analysis. The temporal adjustment for A(H1N1) season in the primary population as well as the temporally adjusted analyses including the unvaccinated GBS/FS cases resulted in a reliable estimation of all model parameters including seasonality. The results of these analyses supported the findings from the unadjusted analyses.

The reason for including unvaccinated GBS/FS cases to estimate seasonal components was to increase the precision of the corresponding estimates. One might argue that the inclusion of unvaccinated cases might introduce bias; however, it should be noted that—in case there had been temporal effects—these effects would be similar in A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases and unvaccinated cases. This assumption seems to be plausible, because both vaccinated and unvaccinated cases occurred in the same geographic area (Germany). Furthermore, neither the temporal distribution of the unvaccinated GBS/FS cases in our study nor the temporal distribution of hospitalization due to GBS/FS in Germany according to data from the German Federal Statistical Office30 indicates an increased incidence of GBS/FS for the time interval November 2009–January 2010.

Overall, we concluded that the discrepancy between the unadjusted analysis and the temporally adjusted analysis restricted to A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases was due to the lack of reliability of the statistical model when adjusting for months, whereas the other temporal adjustments resulted in reliable RI estimates, which supported the findings from the unadjusted analysis.

We did not identify any plausible biologic reason for a temporal effect in this study such as preceding infections. In A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases, a clinically apparent infection within 3 weeks prior to the first GBS/FS symptoms as well as a pathogen proof concerning the preceding infection was reported less frequently than in GBS/FS reports without vaccination. This does not support the hypothesis that concomitant pathogens circulating in the population during the vaccination campaign (e.g., influenza A(H1N1) infection itself) caused the increased number of GBS/FS cases following A(H1N1) vaccination. Furthermore, the significantly increased risk of GBS/FS in A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases in the unadjusted analysis was not substantially altered by excluding patients with preceding gastrointestinal and/or respiratory infection. However, for each individual patient, we cannot prove that the physician has taken the infection history thoroughly and that the patient has given complete and correct information. Thus, regarding infection history, confounding cannot totally be excluded. Besides, A(H1N1) infections—for example—can occur with inconspicuous or without clinical symptoms, and testing for A(H1N1) infection was not routinely conducted in study patients.

Our study design is sensitive toward a potential reporting bias. Theoretically, stimulated reporting during the vaccination campaign and underreporting thereafter might have led to selective reporting by hospitals. However, various analyses did not indicate such selective reporting. As A(H1N1) vaccination had practically stopped by the end of December 2009 in Germany with only a few vaccinations at the beginning of 2010,24 it is assumed that by the middle of February 2010, nearly all GBS/FS cases in the risk period would have occurred, and by the end of May 2010, nearly all cases in the control period would have occurred. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of study reports of unvaccinated cases in the period from February to May 2010 compared with the period from November 2009 to January 2010 (referring to date of GBS/FS onset). This finding does not support the hypothesis of differential reporting of A(H1N1)-vaccinated cases, either. Furthermore, in an additional retrospective survey, the number of cases with ICD discharge diagnosis GBS/FS was determined according to hospital databases. From the result of the survey, it seems unlikely that selective reporting would have occurred to such an extent that the results of the SCCS analyses would have been substantially impacted.

The vaccination status regarding A(H1N1) vaccination could be determined in 656 of all 676 GBS/FS study reports (97.0%). It seems unlikely that the small proportion of reports with unknown vaccination status would have notably affected the study result.

Our results are comparable with results of five studies from the USA,31–35 in which the risk of GBS after receipt of monovalent, inactivated, non-adjuvanted A(H1N1) 2009 vaccine or additionally live-attenuated A(H1N1) vaccine was investigated. The results ranged from a rate ratio of 1.57 (95%CI [1.02, 2.21]) corresponding to 0.74 excess GBS cases per million doses (95%CI [0.04, 1.56])32 to a relative risk of 4.7 (95%CI [1.2, 18.3]) corresponding to 3.9 excess cases per million doses (95%CI [0.0, 7.9]).33 A meta-analysis of A(H1N1) 2009 monovalent inactivated vaccines in the USA found an incidence rate ratio of 2.35 (95%CI [1.42, 4.01]).36 In Quebec where a monovalent, AS03-adjuvanted A(H1N1) vaccine (Arepanrix) was used, the relative risk of GBS during a 4-week post-vaccination period was 2.33 (95%CI [1.19, 4.57]) in an SCCS study and 2.26 (95%CI [1.24, 4.09]) in a cohort study with an attributable risk of approximately two GBS cases per million doses.37 An international SCCS study found an RI of GBS of 2.42 (95%CI [1.58, 3.72]) following A(H1N1) vaccination in a pooled data analysis and 2.09 (95%CI [1.28, 3.42]) using a meta-analytic approach. RI estimates were higher in analyses of unadjuvanted vaccines than in adjuvanted vaccines without a statistically significant difference.38

In contrast to these studies, an SCCS study conducted in the UK found no increased risk of GBS in the 6 weeks following Pandemrix vaccination.39 In a case–control study40 and an SCCS study41 from several European countries, no elevated40 or no significantly elevated risk of GBS41 was observed in adjusted analyses. A retrospective cohort study in Stockholm county,42 a French case–control study,43 and an Australian SCCS study44 found no increased42,43 or no significantly increased risk of GBS following A(H1N1) vaccination.44 However, these three studies were not powered to detect a small risk increase.

Our SCCS analysis regarding seasonal influenza vaccination did not indicate a significantly increased risk of GBS/FS. This corresponds to the results of other studies of seasonal influenza vaccines.5,12–17 Because of the low number of case reports that may be related to the fact that the vaccination campaign already started in September 2009, several weeks prior to the study, the results regarding seasonal influenza vaccination must be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, our data indicate an increased risk of GBS/FS in temporal association with influenza A(H1N1) vaccination (Pandemrix) in Germany. Because of the study design, confounding by temporal effects and by selective reporting cannot totally be excluded. However, several analyses suggest that possible confounding by temporal effects and possible reporting bias were unlikely to have a major impact on the study results. Our results are compatible with other active surveillance studies of both adjuvanted and unadjuvanted pandemic influenza 2009 vaccines.

SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD

Besides Hans-Peter Hartung (chairman) members of the scientific advisory board are Edeltraut Garbe, MD (vice-chairperson, Bremen Institute for Prevention Research and Social Medicine, Bremen); Konrad Beyrer, MD (Governmental Institute of Public Health of Lower Saxony, Hannover); Wiebke Hellenbrand, MD (Robert Koch Institute, Berlin); Rudolf Korinthenberg, MD (Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Division of Neuropediatrics and Muscular Disorders, Albert-Ludwigs University Freiburg); Hilmar W. Prange, MD (Drug Commission of the German Medical Association, Berlin); Ole Wichmann, MD (Robert Koch Institute, Berlin); Thomas Stammschulte, MD (guest of the scientific advisory board, Drug Commission of the German Medical Association, Berlin).

CO-INVESTIGATORS

All co-investigators listed in the following are local site investigators and members of the GBS Study Group. Each of the co-investigators is an MD.

Co-investigators at participating neurologic hospitals

Joachim Gerber (Universitätsklinikum Aachen); Max Heyden (Ostalb-Klinikum Aalen); Christof Klötzsch and Eveline Linster (Kliniken Schmieder, Abteilung Akutneurologie, Allensbach); Stefan Langel (Rheinhessen-Fachklinik Alzey); Wolfgang Bößenecker (Klinikum St. Marien, Amberg); Christian Bamberg (Rhein-Mosel-Fachklinik Andernach); Roland Gerlach and Markus Reckhardt (Bezirksklinikum Ansbach); Peter Borak (St. Johannes-Hospital Arnsberg-Neheim); Holger Braun (Sächsisches Krankenhaus Arnsdorf); Michael Harzheim (Kamillus-Klinik Asbach); Klaus Isenhardt (Klinikum Aschaffenburg); Peter Bader (Schön Klinik Bad Aibling); Franz Glocker (Seidel-Klinik Bad Bellingen); Carl D. Reimers (Zentralklinik Bad Berka); Gertraud Riesterer-Hemm and René Trabold (Caritas-Krankenhaus Bad Mergentheim); Vivien Homberg (HELIOS Klinikum Bad Saarow); Rolf Klee (Segeberger Kliniken, Bad Segeberg); Friedrich von Rosen (Klinikum Staffelstein, Bad Staffelstein); Michael Daffertshofer (Klinikum Mittelbaden, Baden-Baden); Dieter Hofler (Klinikum am Bruderwald, Bamberg); Ulrich Hofstadt von Oy (Klinik Hohe Warte, Klinikum Bayreuth); Christoph Baumsteiger (Rheinische Kliniken Bedburg-Hau); Jens Dreger (Marienkrankenhaus Bergisch Gladbach); Frank Stachulski (Bundeswehrkrankenhaus Berlin); Hendrik Harms (Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin); Andreas Kauert (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth Herzberge, Berlin); Judith Haas (Jüdisches Krankenhaus Berlin); Michael von Brevern (Park-Klinik Weißensee, Berlin); Enrico Völzke (Schlosspark-Klinik Berlin); Franziska Ducke (Vivantes Auguste-Viktoria-Klinikum Berlin); Horst Böhme and Hans-Christian Koennecke (Vivantes Klinikum Am Urban, Berlin); Alexander Ecke and Hans-Christian Koennecke (Vivantes Klinikum im Friedrichshain, Berlin); Dieter Bähr and Darius Günther Nabavi (Vivantes Klinikum Neukölln, Berlin); Dominik Hopmann (Vivantes Klinikum Spandau, Berlin); Dennis Porz (HELIOS Klinikum Berlin-Buch); Ute Grust and Bettina Neumayer (DRK Kliniken Berlin-Köpenick); Thomas Müller (St. Joseph-Krankenhaus Berlin-Weißensee); Martin Kitzrow (Berufsgenossenschaftliches Universitätsklinikum Bergmannsheil, Bochum); Christian Börnke and Alexa Schröder (St. Josef- und St. Elisabeth-Hospital, Klinikum der Ruhr-Universität Bochum); Thomas Kowalski (Universitätsklinikum Knappschaftskrankenhaus Bochum-Langendreer); Johannes Günther (St. Marien-Hospital Borken); David Boeckler and Alexander Reinshagen (HELIOS Klinikum Borna); Michael Sarholz (Knappschaftskrankenhaus Bottrop); Klaus-Dieter Böhm (BDH-Klinik Braunfels); Tobias Weiland (Städtisches Klinikum Braunschweig); Ralf-Jochen Kuhlmann (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Castrop-Rauxel); Wolfgang Heide (Allgemeines Krankenhaus Celle); Steffen Heider (Carl-Thiem-Klinikum Cottbus); Olaf Schüler (Amper Kliniken, Klinikum Dachau); Karsten Schepelmann (Ostseeklinik Damp); Detlef Claus (Klinikum Darmstadt); Erwin Kunesch and Grygoriy Yaretskyy (Bezirksklinikum Mainkofen, Deggendorf); Sybille Spieker (Städtisches Klinikum Dessau, Dessau-Roßlau); Stefan Jung (Caritas-Krankenhaus Dillingen); Christoph Spitzer (Klinikum Dortmund); Alexander Busch (Knappschaftskrankenhaus Dortmund); Hauke Schneider (Universitätsklinikum Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden); Jochen Machetanz (Städtisches Krankenhaus Dresden-Neustadt); Holger Grehl (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Duisburg-Nord); Martina Nolden-Koch (Klinikum Duisburg); Herbert Wilmsen (St. Augustinus Krankenhaus Düren); Helmar Lehmann and Rüdiger Seitz (Universitätsklinikum Düsseldorf); Mechthild Griese (Rheinische Kliniken Düsseldorf); Hans-Michael Schmitt (Martin-Gropius-Krankenhaus am Standort Werner-Forßmann-Krankenhaus, Eberswalde); Christoph Dietze and Jan Holz (Klinikum Emden); Elke Leinisch (HELIOS Klinikum Erfurt); Tobias Derfuß and Ralf Linker (Universitätsklinikum Erlangen); Frank-M. Reinhardt (Klinikum “Am Europakanal,” Erlangen); Markus Krämer (Alfried Krupp Krankenhaus Essen); Susanne Koeppen (Universitätsklinikum Essen); Horst Gerhard (Philippusstift, Katholisches Klinikum Essen); Hartmut Bauer (Marien-Hospital Euskirchen); Henning Stolze (Ev.-Luth. Diakonissenanstalt Flensburg); Volker Jost (Krankenhaus Nordwest, Frankfurt am Main); Helmuth Steinmetz (Klinikum der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main); Hansjörg Schütz (Städtische Kliniken Frankfurt a.M.-Höchst); Josef Böhm (Kreiskrankenhaus Freiberg); Sebastian Rauer (Universitätsklinikum Freiburg); Jürgen M. Klotz (Klinikum Fulda); Andreas Schneider (Evangelische Kliniken Gelsenkirchen); Michael Biemann (SRH Waldklinikum Gera); Franz Blaes and Heidrun Krämer (Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg, Standort Gießen); Kersten Guthke (Städtisches Klinikum Görlitz); Holger Schmidt (Universitätsmedizin Göttingen); Holm Krumpolt (Sächsisches Krankenhaus Großschweidnitz); Dörthe Schiess (Bezirkskrankenhaus Günzburg); Matthias Roth (KMG Klinikum Güstrow); Hans-Hermann Fuchs (Isar-Amper-Klinikum München-Ost, Haar bei München); Edda Schneider (AMEOS Klinikum Haldensleben); Kai Wohlfarth (BG-Kliniken Bergmannstrost, Halle); Tobias Müller (Universitätsklinikum Halle/Saale); Walter Sick (Albertinen-Krankenhaus Hamburg); Dietrich Schwandt (Asklepios Klinik Altona, Hamburg); Ingmar Wellach (Asklepios Klinik Barmbek, Hamburg); Rudolf Friedrich Töpper (Asklepios Klinik Harburg, Hamburg); Jürgen Koehler (Asklepios Klinik Nord-Heidberg, Hamburg); Thorsten Rosenkranz (Asklepios Klinik St. Georg, Hamburg); Sven Knepel (Berufsgenossenschaftliches Unfallkrankenhaus Hamburg); Thomas Duwe (Bundeswehrkrankenhaus Hamburg); Mark Stiller (Schön Klinik Hamburg-Eilbek); Klaus Rieke (St. Marien-Hospital Hamm); Horst Baas (Klinikum Hanau); Peter Brunotte (Klinikum Region Hannover Nordstadt); Johanna Tümmler (Diakoniekrankenhaus Friederikenstift Hannover); Fedor Heidenreich (Diakoniekrankenhaus Henriettenstiftung Hannover); Martin Stangel (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover); Tatjana Stift (Westküstenklinikum Heide); Peter Ringleb (Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg); Stephen Kaendler (Klinikum Heidenheim); Knut Humbroich (Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke); Helmut Plöger and Matthias Sitzer (Klinikum Herford); Jens Dieter Rollnik (BDH-Klinik Hessisch Oldendorf); Maik Dietz (Klinikum Ibbenbüren); Martin Eicke (SHG-Klinikum Idar-Oberstein); Günter Ochs (Klinikum Ingolstadt); Antje Güldenring (Klinikum Itzehoe); Georg Hagemann and Jan Zinke (Universitätsklinikum Jena); Michael Fetter (SRH-Klinikum Karlsbad-Langensteinbach); Harald Herath (Klinikum Kassel); Gabriele Escheu (Bezirkskrankenhaus Kaufbeuren); Robert Stingele (Universitätsklinikum Kiel); Ameli Berthold (Klinik Kipfenberg); Eberhard Schmitt (Katholisches Klinikum Koblenz); Walter F. Haupt (Universitätsklinikum Köln); Hela-F. Petereit (Heilig Geist-Krankenhaus Köln); Volker Limmroth (Kliniken der Stadt Köln, Krankenhaus Köln-Merheim); Hans-Jürgen von Giesen (Krankenhaus Maria-Hilf, Alexianer Krefeld); Benno Kirsch (Ortenau Klinikum Lahr-Ettenheim); Josef G. Heckmann (Klinikum Landshut); Florian Then Bergh (Universitätsklinikum Leipzig); Wolfgang Beuche (Städtisches Klinikum “St. Georg,” Leipzig); Christoph Schattenfroh and Christina Tampier-Pohl (Klinikum Lippe-Lemgo, Lemgo); Raphael Friedl and Christoph Oberwittler (St. Vincenz-Krankenhaus Limburg); Michael Schlenker (Klinikum Main-Spessart, Gesundheitszentrum Lohr am Main); Peter Trillenberg (Universitätsklinikum Lübeck); Ali Abushammala (Klinikum Lüdenscheid); Martin Schabet (Klinikum Ludwigsburg); Marcus Eßer (Klinikum der Stadt Ludwigshafen); Ansgar Thümen (Klinikum Lüneburg); Hartmut Lins (Städtisches Klinikum Magdeburg); Stefan Vielhaber (Universitätsklinikum Magdeburg); Johannes Bayerl (Diakoniekrankenhaus Mannheim); Björn Tackenberg (Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg, Standort Marburg); Christine Schmidt (Klinikum Meiningen); Andreas Hachgenei (Akutabteilung, Glantal-Klinik Meisenheim); Jörg Philipps (Klinikum Minden); Tobias Tings (St. Josef Krankenhaus Moers); Oliver Franz (Kliniken Maria-Hilf, Mönchengladbach); Marek Jauß (Ökumenisches Hainich Klinikum Mühlhausen); Achim Berthele (Klinikum rechts der Isar, TU München); Wolfgang Hupfer (Klinikum Bogenhausen, Städtisches Klinikum München); Michael Nagi (Klinikum Harlaching, Städtisches Klinikum München); Rainer Dziewas (Universitätsklinikum Münster); Wolfgang Kusch (Herz-Jesu-Krankenhaus Münster-Hiltrup); Sabine Lobenstein (Saale-Unstrut Klinikum Naumburg); Volkmar Fischer and Nadeem Syed (Städtisches Klinikum Neunkirchen); Andreas Bitsch (Ruppiner Kliniken, Neuruppin); Uwe Jahnke (Schön Klinik Neustadt, Neustadt in Holstein); Jens Allendörfer (Asklepios Neurologische Klinik Bad Salzhausen, Nidda); Wenke Dietrich (Klinikum Nürnberg Süd); Angelika Görtzen (St. Josef-Hospital, Katholische Kliniken Oberhausen); Erwin Stark (Klinikum Offenbach); Werner Wenning (Ortenau Klinikum Offenburg); Frank Neumann (Klinikum Osnabrück); Marko Petrick (Kreiskrankenhaus Prignitz, Perleberg); Reinhard Kaiser (Klinikum Pforzheim); Torsten Niehoff (Regio Klinikum Pinneberg); Ralph Deymann (Akutneurologie, MediClin Krankenhaus Plau am See); Ronald Hartmann (HELIOS Vogtland-Klinikum Plauen); Walter Christe (Klinikum Ernst von Bergmann, Potsdam); Carsten Görlitz (St. Josefs-Krankenhaus Potsdam); Michael Hotz (Christliches Krankenhaus Quakenbrück); Helmut Buchner (Knappschaftskrankenhaus Recklinghausen); Marco Michels (Elisabeth Krankenhaus Recklinghausen); Klemens Angstwurm (Universitätsklinikum Regensburg); Kathrin Balzer (Krankenhaus Barmherzige Brüder, Regensburg); Hans Joachim Braune (Evangelische Stiftung Tannenhof, Remscheid); Hans-Joachim Kindl (Sana-Klinikum Remscheid); Olaf Leschnik (Sächsisches Krankenhaus für Psychiatrie und Neurologie Rodewisch); Hanns Lohner (Klinikum Rosenheim); Uwe Zettl (Universitätsklinikum Rostock); Reinhard Kiefer (Diakoniekrankenhaus Rotenburg); Sebastian Krauth (Klinikum Saarbrücken); Tjark Hansberg (Nordwest-Krankenhaus Sanderbusch, Sande); Helge Matrisch (Asklepios Klinik Schaufling); Thomas Vetter (Sächsisches Krankenhaus für Psychiatrie und Neurologie Altscherbitz, Schkeuditz); Karsten Schepelmann (Schlei-Klinikum Schleswig MLK); Bernd Schade (Hephata-Klinik Schwalmstadt-Treysa); Alain Nguento (Asklepios Klinikum Uckermark, Schwedt/Oder); Thorsten Fortwängler (Leopoldina-Krankenhaus Schweinfurt); Fritz Hartnack (Kreisklinikum Siegen); Oliver Neuhaus (Kreiskrankenhaus Sigmaringen); Guy Arnold (Klinikum Sindelfingen-Böblingen, Sindelfingen); Michael Wennrich (Hegau-Bodensee-Klinikum Singen); Hans Claus Leopold (St. Lukas Klinik Solingen); Jörg Tebben (Elbe Klinikum Stade); Udo Polzer (Asklepios Fachklinikum Stadtroda); Jörn Peter Sieb (Klinikum Stralsund); Georg-Peter Huss (Bürgerhospital, Klinikum Stuttgart); Valerio Kuhl (Marienhospital Stuttgart); Michael Gawlitza (Knappschaftskrankenhaus Sulzbach); Thomas Freudenberger and Georg Rieder (Klinikum Traunstein); Kerstin Schröder (Krankenhaus der Barmherzigen Brüder, Trier); Monika Bös (St. Johannes-Krankenhaus Troisdorf); Thomas Krüger (AMEOS Diakonie-Klinikum Ueckermünde); Matthias Rechlin (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Unna); Hans-Gerd Will (Schwarzwald-Baar Klinikum Villingen-Schwenningen); Johannes Bufler (Zentralklinikum Wasserburg am Inn); Michael Angerer (Klinikum Weiden); Peter Möller (Sophien- und Hufeland-Klinikum Weimar); Burckhardt Eppinger (Klinikum am Weissenhof, Weinsberg); Frank Dömges (Harz-Klinikum Wernigerode-Blankenburg); Peter Albrecht (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Wesel); Sylvia Kotterba (Ammerland-Klinik Westerstede); Erwin Stolz (Klinikum Wetzlar); Nikolaus Schmidt (Dr.-Horst-Schmidt-Kliniken Wiesbaden); Thomas Trottenberg (Zentrum für Psychiatrie Winnenden); Philipp Feige (Klinik Bosse Wittenberg); Andreas Hufschmidt (Verbundkrankenhaus Bernkastel/Wittlich, Wittlich); Lidia Svrakova (Klinikum Worms); Carl-Albrecht Haensch (HELIOS Klinikum Wuppertal); Frank Kastrau and Patrick Schmidt (Medizinisches Zentrum StädteRegion Aachen, Würselen-Bardenberg); Karlheinz Reiners (Universitätsklinikum Würzburg); Erik Weinmann (Stiftung Juliusspital Würzburg); Jörn A. Zeller (St. Josef-Krankenhaus Zell/Mosel); Stefan Merkelbach (Heinrich-Braun-Klinikum Zwickau); Armin Bachhuber and Wieland Hermann (Paracelsus-Klinik Zwickau).

Co-investigators at participating pediatric hospitals

Martin Häusler (Universitätsklinikum der RWTH Aachen); Monika Toth (Ostalb-Klinikum Aalen); Bernt Martin Weiß (Robert-Koch-Krankenhaus Apolda); Detlef Stein (Ilm-Kreis-Kliniken Arnstadt-Ilmenau); Jörg Klepper (Klinikum Aschaffenburg); Thomas Hirsch (Sana-Krankenhaus Rügen, Bergen); Arpad von Moers (DRK Kliniken Westend, Berlin); Heiko Brandes (St. Joseph-Krankenhaus Berlin); Micha Botsch (Evangelisch-Freikirchliches Krankenhaus Bernau); Cornelia Köhler (St. Josefs-Hospital, Universitätsklinikum Bochum); Ingo Franke (Universitätsklinikum Bonn); Hans Kössel (Städtisches Klinikum Brandenburg); Birgit Kauffmann (Klinikum Links der Weser, Bremen); Hanno Schwalm (Klinikum Bremen-Mitte); Martin Kirschstein (Allgemeines Krankenhaus Celle); Ulrich Tribukait (DRK Krankenhaus Chemnitz-Rabenstein); Michael Mandl (Klinikum Deggendorf); Hans Böhmann (Klinikum Delmenhorst); Kirstin Schaetz (Städtisches Klinikum Dessau, Dessau-Roßlau); Burkhard Hebing (Klinikum Lippe-Detmold, Detmold); Martin Steinert (Klinikum Dortmund); Stephan Eichholz (Städtisches Krankenhaus Dresden-Neustadt); Tassilo von Lilien-Waldau (Kaiserswerther Diakonie, Florence-Nightingale-Krankenhaus, Düsseldorf); Michael Karenfort (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Klinik für Allgemeine Pädiatrie); Benno Kretzschmar (St. Georg Klinikum Eisenach); Regina Trollmann (Universitätsklinikum Erlangen); Gudrun Schmiedel (Klinikum Esslingen); Michael Dördelmann (Diakonissenkrankenhaus Flensburg); Matthias Kieslich (Klinikum der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main); Ulrike Mause (Städtische Kliniken Frankfurt a.M.–Höchst); Christoph Grüber (Klinikum Frankfurt/Oder); Rudolf Korinthenberg (Universitätsklinikum Freiburg, Klinik für Neuropädiatrie und Muskelerkrankungen); Georg Heubner (Weißeritztal-Kliniken, Freital); Jasmin Mattes (Krankenhaus Freudenstadt); Udo Radlow (Klinikum Friedrichshafen); Reinald Repp (Klinikum Fulda); Jens Klinge (Klinikum Fürth); Rainer Genseke (Altmark-Klinikum, Krankenhaus Gardelegen); Stefan Gsinn (Klinikum Garmisch-Partenkirchen); Boris Gebhardt (Main-Kinzig-Kliniken Gelnhausen); Matthias Papsch (Marienhospital Gelsenkirchen); Suhail Mutlak (Klinikum Gifhorn); Knut Brockmann (Universitätsklinikum Göttingen, Abteilung Pädiatrie II mit Schwerpunkt Neuropädiatrie); Gerhard Koch (Allgemeines Krankenhaus Hagen); Frank Mandelkow (Kreiskrankenhaus Hagenow); Philipp v. Blanckenburg (Kreiskrankenhaus Hameln); Uwe Bertram (Klinikum Hanau); Silvia Vieker (Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Herdecke); Hans-Ulrich Peltner (St. Bernward Krankenhaus Hildesheim); Marina Sander (Sana Klinikum Hof); Mohammed Ghiath Shamdeen (Universitätsklinikum des Saarlandes, Homburg); Sigrid Nowka (St. Ansgar-Krankenhaus Höxter); Walter Koch (Klinikum Idar-Oberstein); Hartmut Walkenhorst (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Bethanien Iserlohn); Thomas Rubens (Kliniken Ostallgäu-Kaufbeuren, Kaufbeuren); Klaus Westerbeck (Städtisches Krankenhaus Kiel); Jochen Rübo (St. Antonius-Hospital Kleve); Torsten Sandrieser (Gemeinschaftsklinikum Koblenz-Mayen); Alfred Wiater (Krankenhaus Porz am Rhein, Köln); Karin Pflumm (Klinikum Konstanz); Jürgen Bensch (Vinzentius-Krankenhaus Landau); Harald Engelhardt (Kinderkrankenhaus St. Marien, Landshut); Margot Deja (Klinikum Leer); Michael Borte (Klinikum St. Georg, Leipzig); Volker Schuster (Universitätsklinikum Leipzig); Daniel Tibussek (Klinikum Leverkusen); Henry Bosse (St. Bonifatius-Hospital Lingen); Karla Rinschen (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Lippstadt); Christoph Härtel (Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Lübeck); Michael Gaude-Wagener (Klinikum Lüneburg); Uta Beyer (Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, Klinik für Allgemeine Pädiatrie und Neonatologie); Helmut Peters (Kinderneurologisches Zentrum Mainz); Frank Kowalzik (Universitätsmedizin Mainz); Peter Seipelt (Universitätsklinikum Gießen und Marburg, Standort Marburg); Stephanie Zippel (Kreiskrankenhaus Mechernich); Kai Nils Pargac (Elblandkliniken Meißen-Radebeul, Meißen); Axel Schobeß (Carl-von-Basedow-Klinikum Merseburg); Wolfgang Müller (Krankenhaus Neuwerk “Maria von den Aposteln,” Mönchengladbach); Martina Baethmann, Steffen Leiz (Kinderklinik Dritter Orden München); Armin Gehrmann (Klinikum Harlaching, Städtisches Klinikum München); Christine Makowski (Klinikum Schwabing, Städtisches Klinikum München); Barbara Fiedler (Universitätsklinikum Münster); Michael Böswald (St. Franziskus-Hospital Münster); Tanja Weisbrod (Stauferklinikum Mutlangen); Kathrin Kintzel (Havellandklinik Nauen); Christel Franz (Saale-Unstrut Klinikum Naumburg); Gereon Schädler (Fachkrankenhaus Neckargemünd); Hans-Joachim Feickert (Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Klinikum Neubrandenburg); Peter Gonne Kühl (Städtische Kliniken Neuss, Lukaskrankenhaus); Michael Schneider (Klinikum Neustadt); Klaus Raab (Cnopf'sche Kinderklinik Nürnberg); Peter Beyer (Evangelisches Krankenhaus Oberhausen); Klaus-Dieter Kauther (St. Vincenz-Krankenhaus Paderborn); Hans-Ludwig Reiter (Klinikum Pforzheim); Georg Heubner (Klinikum Pirna); Eva-Susanne Behl (Klinikum Ernst von Bergmann, Potsdam); Friedrich K. Trefz (Klinikum am Steinenberg, Reutlingen); Hans-Georg Hoffmann (Mathias-Spital Rheine); Michael Buss (RoMed Klinikum Rosenheim); Dirk M. Olbertz (Klinikum Südstadt Rostock); Lutz Hempel (Thüringen-Kliniken “Georgius Agricola,” Saalfeld); Gerd Horneff (Asklepios Kinderklinik Sankt Augustin); Walter Mihatsch (Diakonie-Klinikum Schwäbisch Hall); Anja Kurre (Leopoldina-Krankenhaus Schweinfurt); Steffi Colling (HELIOS Klinikum Schwerin); Rainer Burghard (DRK-Kinderklinik Siegen); Volker Soditt (Städtisches Klinikum Solingen); Kristin Feierfeil, Daniela Hornbrook (Elbe Klinikum Stade); Lars Kellner (Klinikum Starnberg); Walter Pernice (Kreiskrankenhaus “Johann Kentmann,” Torgau); Doris Schirmer (Klinikum Traunstein); Michael Alber (Universitätsklinikum Tübingen, Abteilung für Kinderheilkunde III); Swen Geerken (Kliniken Uelzen und Bad Bevensen, Uelzen); Michael Kratz (Rems-Murr-Klinik Waiblingen); André Köhler (Sophien- und Hufeland-Klinikum Weimar); Markus Knuf (Dr.-Horst-Schmidt-Kliniken Wiesbaden); Tetyana Repinska (Reinhard-Nieter-Krankenhaus Wilhelmshaven); Maria Buller (Hanse-Klinikum Wismar); Jan-Claudius Becker (Marien-Hospital Witten); Christian Niesytto (Kreiskrankenhaus Wolgast); Heino Skopnik (Klinikum Worms); Peter Borusiak (HELIOS Klinikum Wuppertal); Tilman Verbeek (Klinikum des Landkreises Löbau-Zittau, Zittau); Ingrid Gabler, Thomas Winkelmann (Heinrich-Braun-Klinikum Zwickau).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Financial activities exist outside the submitted work: Dr. Hartung has received payment from Bayer HealthCare, Baxter, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, Roche, and CSL Behring for both consultancy and lectures and from GeNeuro for consultancy.

The institution of Dr. Lehmann has received grants from Baxter. Dr. Lehmann has been paid from Fresenius for lectures, and travel/accommodation/meeting expenses of Dr. Lehmann have been paid by CSL Behring, Grifols, and Pfizer. There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Dr. Prestel, Dr. Volkers, Dr. Mentzer, and Dr. Keller-Stanislawski have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

KEY POINTS

The results of our SCCS study indicate an increased risk of GBS/FS in temporal association with adjuvanted pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 vaccination in Germany.

Sensitivity analyses suggest that possible confounding by temporal effects and possible reporting bias were unlikely to have a major impact on the study results.

The risk of GBS observed in our study is lower than that observed following the 1976 swine influenza vaccination campaign in the USA.

Although not all studies of pandemic influenza 2009 vaccines have shown an elevated risk of GBS, our results are in line with the outcome of several other active surveillance studies of both adjuvanted and unadjuvanted pandemic influenza 2009 vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the co-investigators at the participating neurologic and pediatric hospitals throughout Germany. The study would not have been possible without their cooperation and efforts.

We would also like to express our gratitude to the members of the scientific advisory board whose comments, advice, and constructive criticism ensured the quality of the study.

We also thank Cornelia Witzenhausen (PEI, Langen) for extensive secretarial work; Markus Funk, MD (PEI, Langen), for communication with the ethics committee and for his support in the preparation of the reporting form; and Serife Günay, MD, and Lothar Heymans, MD (PEI, Langen), for data collection.

STUDY FUNDING

The study was exclusively sponsored by the PEI. There was no funding of the submitted work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J. Prestel contributed to drafting of the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis and interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and study coordination. P. Volkers contributed to drafting of the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis and interpretation of data, and statistical analysis. D. Mentzer contributed to the revision of the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis of data, and acquisition of data. H.C. Lehmann contributed to the revision of the manuscript, analysis of data, and acquisition of data. H.-P. Hartung contributed to the revision of the manuscript, study concept or design, interpretation of data, and study supervision. B. Keller-Stanislawski contributed to drafting of the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis and interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and study supervision and coordination. All authors approved this version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Kieseier BC, Kiefer R, Gold R, Hemmer B, Willison HJ, Hartung HP. Advances in understanding and treatment of immune-mediated disorders of the peripheral nervous system. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:131–156. doi: 10.1002/mus.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrogan A, Madle GC, Seaman HE, de Vries CS. The epidemiology of Guillain–Barré syndrome worldwide. A systematic literature review. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32:150–163. doi: 10.1159/000184748. . doi:10.1159/000184748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann HC, Köhne A, Meyer zu Hörste G, Kieseier BC. Incidence of Guillain–Barré syndrome in Germany. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:285. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2007.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuki N, Hartung HP. Guillain–Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2294–2304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1114525. . doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann HC, Hartung HP, Kieseier BC, Hughes RA. Guillain–Barré syndrome after exposure to influenza virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:643–651. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70140-7. . doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann HC, Hughes RA, Kieseier BC, Hartung HP. Recent developments and future directions in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2012;17(suppl 3):57–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00433.x. . doi:10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker G, Zurynski Y, Buttery J. Neurologic complications of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09: surveillance in 6 pediatric hospitals. Neurology. 2012;79:1474–1481. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826d5ea7. . doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826d5ea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaari A, Bahloul M, Dammak H. Guillain–Barré syndrome related to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) infection. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1275. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1895-4. . doi:10.1007/s00134-010-1895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlesa M, Santini M, Krajinovic V, Raffanelli D, Barsic B. Acute motor axonal neuropathy associated with pandemic H1N1 influenza A infection. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:98–100. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9365-y. . doi:10.1007/s12028-010-9365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ. Guillain–Barre syndrome following vaccination in the National Influenza Immunization Program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:105–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safranek TJ, Lawrence DN, Kurland LT. Reassessment of the association between Guillain–Barré syndrome and receipt of swine influenza vaccine in 1976–1977: results of a two-state study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:940–951. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K, Alamario DA, Wizemann T, McCormick MC, editors. Immunization Safety Review: Influenza Vaccines and Neurological Complications. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 45–95. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2003/Immunization-Safety-Review-Influenza-Vaccines-and-Neurological-Complications.aspx [16 September 2013] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RA, Charlton J, Latinovic R, Gulliford MC. No association between immunization and Guillain–Barré syndrome in the United Kingdom, 1992 to 2000. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1301–1304. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.12.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz ES, Schonberger LB, Nelson DB, Holman RC. Guillain–Barré syndrome and the 1978–1979 influenza vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1557–1561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198106253042601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JE, Katona P, Hurwitz ES, Schonberger LB. Guillain–Barré syndrome in the United States, 1979–1980 and 1980–1981. Lack of an association with influenza vaccination. JAMA. 1982;248:698–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscelli JD, Bass JW, Pang L. Guillain–Barré syndrome and influenza vaccination in the US army, 1980–1988. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:952–955. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe J, Andrews N, Wise L, Miller E. Investigation of the temporal association of Guillain–Barré syndrome with influenza vaccine and influenzalike illness using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:382–388. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn310. . doi:10.1093/aje/kwn310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juurlink DN, Stukel TA, Kwong J. Guillain–Barré syndrome after influenza vaccination in adults: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2217–2221. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky T, Terracciano GJ, Magder L. The Guillain–Barré syndrome and the 1992–1993 and 1993–1994 influenza vaccines. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1797–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812173392501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP, Spiessens B, Musonda P. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med. 2006;25:1768–1797. doi: 10.1002/sim.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington CP. Relative incidence estimation from case series for vaccine safety evaluation. Biometrics. 1995;51:228–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP. The methodology of self-controlled case series studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18:7–26. doi: 10.1177/0962280208092342. . doi:10.1177/0962280208092342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington CP, Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN. Case series analysis for censored, perturbed, or curtailed post-event exposures. Biostatistics. 2009;10:3–16. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn013. . doi:10.1093/biostatistics/kxn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter D, Böhmer MM, Heiden M, Reiter S, Krause G, Wichmann O. Monitoring pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccination coverage in Germany 2009/10—results from thirteen consecutive cross-sectional surveys. Vaccine. 2011;29:4008–4012. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.069. . doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sejvar JJ, Kohl KS, Gidudu J. Guillain–Barré syndrome and Fisher syndrome: case definitions and guidelines for collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2011;29:599–612. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.003. . doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison C, Turnbull BW. Group Sequential Methods with Applications to Clinical Trials. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weldeselassie YG, Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP. Use of the self-controlled case-series method in vaccine safety studies: review and recommendations for best practice. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139:1805–1817. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001531. . doi:10.1017/S0950268811001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua W, Sun G, Dodd CN. A simulation study to compare three self-controlled case series approaches: correction for violation of assumption and evaluation of bias. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:819–825. doi: 10.1002/pds.3451. . doi:10.1002/pds.3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann O, Stöcker P, Poggensee G. Pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 breakthrough infections and estimates of vaccine effectiveness in Germany 2009–2010. Euro Surveill. 2010;15 : pii:19561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German Federal Statistical Office [Statistisches Bundesamt] Statistics about cases with ICD-diagnosis GBS/FS according to ICD-hospital databases in Germany, categorized by month of hospital admission [“DRG-Statistik”]. Personal communication on 30-Nov-2012.

- Tokars JI, Lewis P, DeStefano F. The risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine and 2009–2010 seasonal influenza vaccines: results from self-controlled analyses. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:546–552. doi: 10.1002/pds.3220. . doi:10.1002/pds.3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise ME, Viray M, Sejvar JJ. Guillain–Barré syndrome during the 2009–2010 H1N1 influenza vaccination campaign: population-based surveillance among 45 million Americans. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1110–1119. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws196. . doi:10.1093/aje/kws196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene SK, Rett M, Weintraub ES. Risk of confirmed Guillain–Barré syndrome following receipt of monovalent inactivated influenza A (H1N1) and seasonal influenza vaccines in the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project, 2009–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1100–1109. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws195. . doi:10.1093/aje/kws195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yih WK, Lee GM, Lieu TA. Surveillance for adverse events following receipt of pandemic 2009 H1N1 vaccine in the Post-Licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring (PRISM) System, 2009–2010. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1120–1128. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws197. . doi:10.1093/aje/kws197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polakowski LL, Sandhu SK, Martin DB. Chart-confirmed Guillain–Barré syndrome after 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination among the Medicare population. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:962–973. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt051. . doi:10.1093/aje/kwt051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon DA, Proschan M, Forshee R. Association between Guillain–Barré syndrome and influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent inactivated vaccines in the USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62189-8. . doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wals P, Deceuninck G, Toth E. Risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome following H1N1 influenza vaccination in Quebec. JAMA. 2012;308:175–181. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7342. . doi:10.1001/jama.2012.7342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd CN, Romio SA, Black S. International collaboration to assess the risk of Guillain Barré syndrome following influenza A(H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;31:4448–4458. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.032. . doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews N, Stowe J, Al-Shahi Salman R, Miller E. Guillain–Barré syndrome and H1N1 (2009) pandemic influenza vaccination using an AS03 adjuvanted vaccine in the United Kingdom: self-controlled case series. Vaccine. 2011;29:7878–7882. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.069. . doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieleman J, Romio S, Johansen K. Guillain–Barré syndrome and adjuvanted pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccine: multinational case–control study in Europe. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3908. : d3908. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romio S, Weibel D, Dieleman JP. Guillain–Barré syndrome and adjuvanted pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 vaccines: a multinational self-controlled case series in Europe. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082222. : e82222. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardage C, Persson I, Örtqvist A, Bergman U, Ludvigsson JF, Granath F. Neurological and autoimmune disorders after vaccination against pandemic influenza A(H1N1) with a monovalent adjuvanted vaccine: population based cohort study in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5956. : d5956. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.d5956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Alpérovitch A, Besson G. Guillain-Barré syndrome, influenzalike illnesses, and influenza vaccination during seasons with and without circulating A/H1N1 viruses. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:326–335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr072. . doi:10.1093/aje/kwr072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NW, Cheng A, Andrews N. Guillain–Barré syndrome following pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A immunisation in Victoria: a self-controlled case series. Med J Aust. 2012;197:574–578. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10534. . doi:10.5694/mja12.10534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]