Abstract

The pathogenesis and therapy of Shigatoxin 2 (Stx2)-mediated kidney failure remain controversial. Our aim was to test whether, during an infection with Stx2-producing E. coli (STEC), Stx2 exerts direct effects on renal tubular epithelium and thereby possibly contributes to acute renal failure. Mice represent a suitable model because they, like humans, express the Stx2-receptor Gb3 in the tubular epithelium but, in contrast to humans, not in glomerular endothelia, and are thus free of glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). In wild-type mice, Stx2 caused acute tubular dysfunction with consequent electrolyte disturbance, which was most likely the cause of death. Tubule-specific depletion of Gb3 protected the mice from acute renal failure. In vitro, Stx2 induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and apoptosis in human tubular epithelial cells, thus implicating a direct effect of Stx2 on the tubular epithelium. To correlate these results to human disease, kidney biopsies and outcome were analysed in patients with Stx2-associated kidney failure (n = 11, aged 22–44 years). The majority of kidney biopsies showed different stages of an ongoing TMA; however, no glomerular complement activation could be demonstrated. All biopsies, including those without TMA, showed severe acute tubular damage. Due to these findings, patients were treated with supportive therapy without complement-inhibiting antibodies (eculizumab) or immunoadsorption. Despite the severity of the initial disease [creatinine 6.34 (1.31–17.60) mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 1944 (753–2792) U/l, platelets 33 (19–124)/nl and haemoglobin 6.2 (5.2–7.8) g/dl; median (range)], all patients were discharged after 33 (range 19–43) days with no neurological symptoms and no dialysis requirement [creatinine 1.39 (range 0.84–2.86) mg/dl]. The creatinine decreased further to 0.90 (range 0.66–1.27) mg/dl after 24 months. Based on these data, one may surmise that acute tubular damage represents a separate pathophysiological mechanism, importantly contributing to Stx2-mediated acute kidney failure. Specifically in young adults, an excellent outcome can be achieved by supportive therapy only. © 2014 The Authors. The Journal of Pathology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Keywords: acute renal failure; acute tubular damage; electron microscopy; globoside (Gb3, CD77); Shigatoxin; Shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC); thrombotic microangiopathy

Introduction

In 1983, E. coli O157:H7 was recognized as a human pathogen inducing haemorrhagic colitis 1. Subsequently, an association between post-diarrhoeal haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) and the production of Shigatoxin 2 (Stx2) was established 2, and Stx2-producing E. coli (STEC) continuously attract attention in association with repetitive outbreaks of food-borne illnesses throughout the world 3,4 (reviewed in 5–7). In 2011, an epidemic of STEC spread through Germany; 3816 cases of acute gastroenteritis, 845 cases of HUS and 54 deaths were attributed to the infection 8; predominantly young adult females were affected 8. Stool contained the unusual E. coli strain O104:H4 with characteristics of STEC and enteroaggregative E. coli 9–11.

The pathogenetic sequence of STEC-associated human disease is unknown. The toxin accesses the circulation during colitis. Globotrihexosylceramide (Gb3 or CD77) functions as the cellular Stx2 receptor 12. Stx2–Gb3 interaction leads to Stx2 internalization and retrograde transport to the endoplasmic reticulum, where it irreversibly inactivates ribosomes and interferes with proteosynthesis 7. In addition, effects on intracellular signalling, increased production of proinflammatory cytokines and physicochemical modes of Stx2 action on plasma membrane, including bending of the membrane lipid bilayer and perturbation of lipid clustering, have been discussed 13–16.

The clinical manifestations are variable 17. Acute neurological complications develop in about 25% of patients 18. The majority of patients show acute renal failure, but its development is not correlated to the degree of haemolysis and thrombocytopenia, which warrant the diagnosis of HUS 18,19. In the German 2011 epidemic, 22% of patients with acute enteritis met the criteria for HUS 8. These data suggest that kidney failure is not necessarily linked to thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and haemolysis. Thus, other mechanisms inducing kidney failure may play a role during infection with STEC.

The appropriate management of STEC infections remains a challenge 20. Recently, eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody neutralizing complement factor C5, has been implemented for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria and atypical (ie STEC-unrelated) HUS 21–23. Early during the outbreak of the 2011 epidemic, a successful therapy in three children with STEC-related HUS was reported 24. In response, eculizumab was tested as a 'rescue therapy' in over 300 patients. However, analyses of the clinical data have been unable to demonstrate significant benefits of this treatment 25,26.

Our goal in this report was to obtain an insight into the processes involved in the kidney failure elicited by STEC; we investigated Stx2 effects in vivo on murine models and in vitro on tubular epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Histology

The review board of the Goethe-University Hospital in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, approved the analysis of the patient data. Tissue samples were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde, paraffin-embedded and subjected to routine diagnostic procedures: periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Goldner's trichrome staining, immunohistochemistry for IgA, IgG, IgM, C1q, C3, fibrin/fibrinogen (Dako, Hamburg, Germany) and electron microscopy (see also supplementary material, Supplementary materials and methods). The alkaline phosphatase/anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP) and avidin-biotinylated enzyme complex (ABC) methods were performed as described 27. Chloracetate esterase (CAE) staining was performed as described 28. For Gb3 immunohistochemistry, formalin-fixed tissue was incubated in 30% sucrose overnight and stored at −80 °C; cryosections were probed with polyclonal chicken anti-Gb3 antibody JM06/298-1 29, followed by alkaline phosphatase-conjugated polyclonal donkey anti-IgY secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Europe, Suffolk, UK). Sections were scanned using a confocal laser microscope (TCS-SL, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Glomerular TMA was semi-quantified on a PAS-stained slide by scoring the extent of TMA in each glomerulus as: 0, absent; 0.5, present in one-quarter of the glomerulus; 1, present in one-half; 2, present in three-quarters; and 3, encompassing the whole glomerulus. The percentage representation of each score was calculated. The total score was built by adding these percentages, multiplied by the corresponding score (eg a case with 100% globally thrombosed glomeruli would reach the maximum score of 300).

Similarly, the acute tubular damage was assessed: Cortical tubular epithelial cells were first separately evaluated for the extent of: (a) brush border loss in proximal tubules; (b) epithelial cell flattening; and (c) vacuolization. Each phenomenon was separately scored as: 0, absent; 0.5, discretely present; 1, slightly present; 2, moderately present; and 3, severely present. In analogy to the evaluation of glomeruli, here the score for each of the three parameters was also calculated as the sum of the percentage representation of each score, multiplied by the score itself (ie leading to values in the range 0–300). The acute tubular damage of each case was expressed by adding the scores for brush border loss, epithelial cell flattening and vacuolization (ie leading to values in the range 0–900).

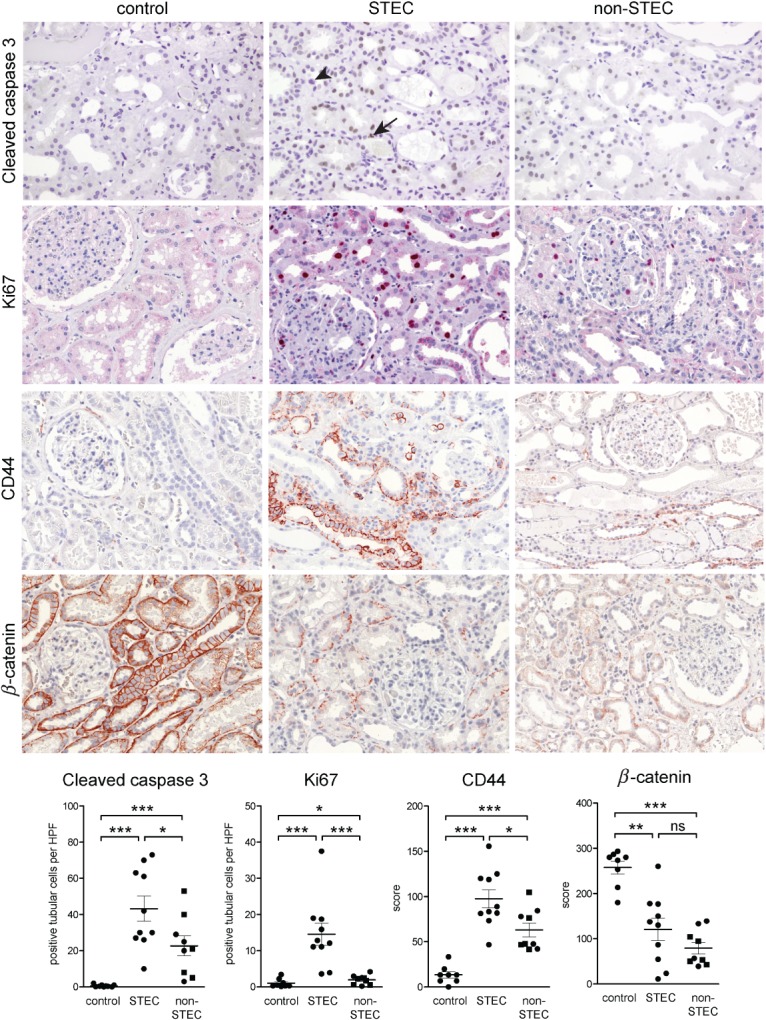

For evaluation of the immunohistochemistry for β-catenin and CD44, the staining was scored on tubular cells in each high-power field (HPF) as: 0, no staining detectable; 1, faint staining; 2, moderate staining; and 3, intense staining. The staining score was calculated by adding all staining intensities multiplied by the percentage of fields, showing the respective staining intensity. In case of the immunohistochemistry for Ki67 and cleaved caspase 3, the number of positive tubular cells was expressed as average cell number/HPF (×400 magnification). In case of the immunohistochemistry for CD3 and CD68 and CAE staining, the number of positive cortical interstitial cells was expressed as average cell number/HPF.

For electron microscopy, tissue was post-fixed in Karnovsky´s glutaraldehyde (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 0.2 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) and embedded in araldite (Serva Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany). Ultrathin sections were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate. Electron micrographs were taken on a Zeiss EM 910 electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Animal models

Gb3S−/− (A4galttm1.1Poru) and Ugcgfl/fl (Ugcgtm1.1Hjg) mice were generated by our group 30,31. Pax8cre, PF4cre and Tie2cre have been reported previously 32–34. As all strains were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 genetic background for > 10 generations, we used C57BL/6 mice as wild-type controls. For induction of Cre activity in the Tie2cre strain, mice were injected with 1 mg tamoxifen (Sigma, Schnelldorf, Germany) in 100 µl sunflower oil on five consecutive days. Eight week-old mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 0.2 µg Stx2 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) dissolved in 200 µl PBS. Measurement of the endotoxin concentration in the Stx2 stock solution was performed by Mikrobiologisches Labor (Münster, Germany). The amount of LPS co-administered with one Stx2 dose was 1.32 × 10−3 endotoxin units (EU)/mouse (0.066 EU/kg body weight), which corresponds approximately to 0.132 pg LPS/mouse. In the case of LPS injection, mice were injected i.p. with 40 µg LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 (Sigma).

Urine was collected in metabolic cages with water access ad libitum. Urine and blood were analysed on a Hitachi 9-17E analyser (Hitachi Chemical, Düsseldorf, Germany). Animal experiments were approved by the institutional board and the corresponding local authority.

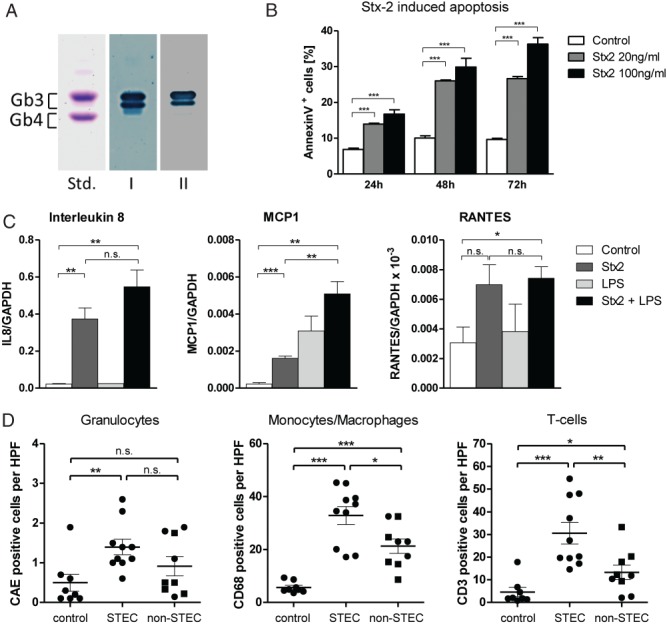

In vitro investigations on HK-2 cells

HK-2 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin 35. The cells were grown to 80% confluence and switched to medium without FCS overnight. Stx2 and/or LPS (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) were applied in medium without FCS. Thin-layer chromatography and immuno-overlays were performed as detailed 36. Apoptosis was measured using Annexin V (Apoptosis Detection Kit, BD, Heidelberg, Germany). Gene expression was analysed as described in 27, using primers as detailed in Supplementary materials and methods.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test or Student's t-test were performed to compare datasets. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Results

In mice, Shigatoxin 2 caused a direct toxic effect on renal tubular epithelium with consequent acute renal failure

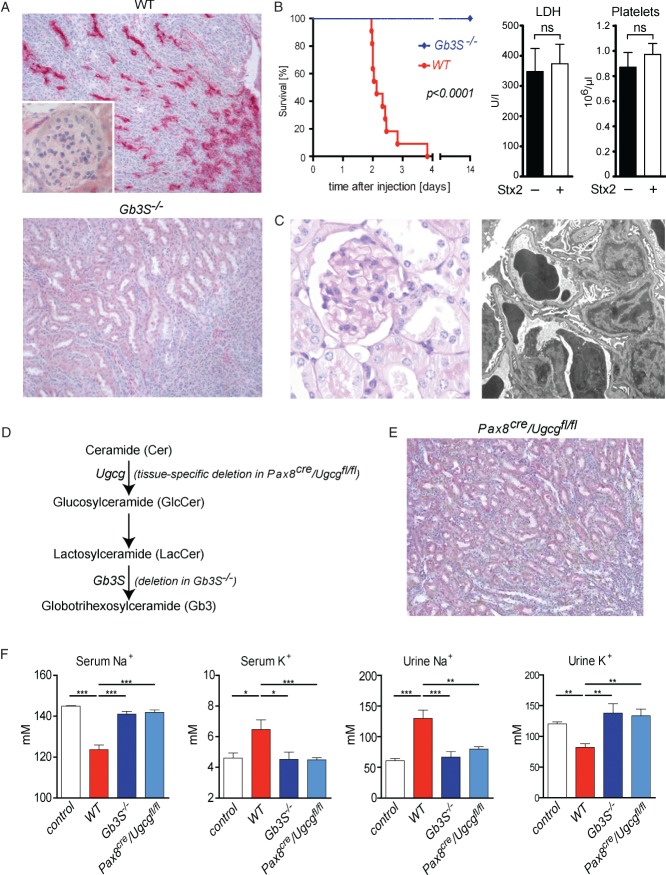

Mice represented a suitable model to analyse the TMA-unrelated effects of Stx2 on kidney cells in vivo, because they, in contrast to humans, do not express the Stx2 receptor Gb3 on renal endothelial cells, under either native or LPS-stimulated conditions (Figure 1A; see also supplementary material, Figure S1). As visualized by a complete co-localization with aquaporin 2, the expression of Gb3 was restricted to collecting ducts in the murine kidney (see supplementary material, Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Stx2 exerts direct toxic effects towards tubular epithelial cells. (A) Indirect immunohistochemistry using primary anti-Gb3 antibodies in combination with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies visualized Gb3 expression in collecting ducts but not in glomerular or renal endothelial cells of WT mice. In Gb3S-deficient (Gb3S−/−) mice, Gb3 expression was completely abolished; magnification = ×200. (B) WT and Gb3S−/− mice were injected with 0.2 µg Stx2 i.p. While all WT mice died 2–4 days after the injection, all Gb3S−/− mice survived and showed no abnormalities. In moribund Stx2-injected WT mice, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and platelet counts were measured 36 h after the injection of Stx2. No increase in LDH or decrease of platelet count could be observed, as compared to PBS-injected control WT mice (n = 5/group). (C) Consistent with the absence of Gb3 in the murine glomerulus, TMA could not be detected in the glomeruli of moribund mice. Upon light and transmission electron microscopy, the glomerular morphology was unremarkable; in particular, no signs of endothelial damage or TMA could be detected by electron microscopy: (left panel) PAS staining, magnification = ×400; (right panel) electron micrograph, lead citrate/uranyl acetate staining, magnification = ×6300. (D) Scheme of the synthesis of globotrihexosylceramide (Gb3), starting with ceramide (Cer). Successive additions of one glucose (Glc) and two galactose moieties result in the formation of Gb3. The last step is catalysed by Gb3 synthase (Gb3S) and is defective in Gb3S−/− mice. Tissue-specific depletion of Gb3 was achieved by deletion of the UDP-glucose:ceramide glucosyltransferase (Ugcg) gene, which encodes for the enzyme catalysing the synthesis of glucosylceramide (GlcCer) two steps upstream of Gb3S. (E) Immunohistochemistry for Gb3 performed as in (A), revealed no tubular staining in the kidneys of Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice as contrasted to WT (cf A); magnification = ×200. (F) 36 h after the Stx2-injection, serum and urine analysis showed profound and significant hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia mirrored by inverse changes in urine sodium and potassium in WT mice. In contrast, global (Gb3S−/−) as well as tubule-specific depletion of Gb3 (Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl) were fully protective. PBS-injected mice served as controls (n = 5/group); bars in (B, F) show mean ± SEM; statistical differences were tested by two-tailed Student's t-test; ns, non-significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

After i.p. injection of 0.2 µg Stx2, WT mice died between days 2 and 4 (Figure 1B). In contrast, all Gb3-deficient mice survived the Stx2 injection without any deterioration of their general status or histological abnormalities. Consistent with the absence of Gb3 in the murine glomerulus and renal blood vessels, TMA was not observed in moribund WT mice 36 h after the Stx2 injection (Figure 1C). In line with this, these mice did not show any elevation of serum LDH or any decrease in platelets (Figure 1B). Similarly, no depositions of complement factor C3 were detected in glomeruli and renal blood vessels upon Stx2 administration (see supplementary material, Figure S3). Despite this, Stx2-injected WT mice showed a significant (p < 0.01) increase in serum creatinine (PBS-injected WT 0.12 ± 0.006 mg/dl, versus Stx2-injected WT 0.22 ± 0.024 mg/dl; mean ± SEM, n = 14 and n = 8, respectively) and significant hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia (Figure 1F). These changes were accompanied by an elevated sodium concentration as well as a decreased potassium concentration in the urine, thus indicating profound renal tubular dysfunction. The serum electrolyte dysregulation and not TMA was therefore the likely cause of death in the WT mice.

To verify that Stx2 toxicity towards the tubular epithelium is causative in the development of these changes, we used a mouse with tubule-specific Gb3 deficiency. To this end, we crossed the Ugcgfl/fl mouse to a strain with tubule-specific Cre activity (Pax8cre), thereby eliminating the synthesis of glycosphingolipids two steps upstream from Gb3 synthase (Figure 1D, E). Similar to the mice with a global Gb3 deficiency, the mice with a tubule-specific Gb3 deficiency (Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl) were fully protected from the toxic effects of Stx2 towards the renal epithelium (Figure 1F), further strengthening the notion that the tubular damage was causative in mediating the lethal Stx2 effects.

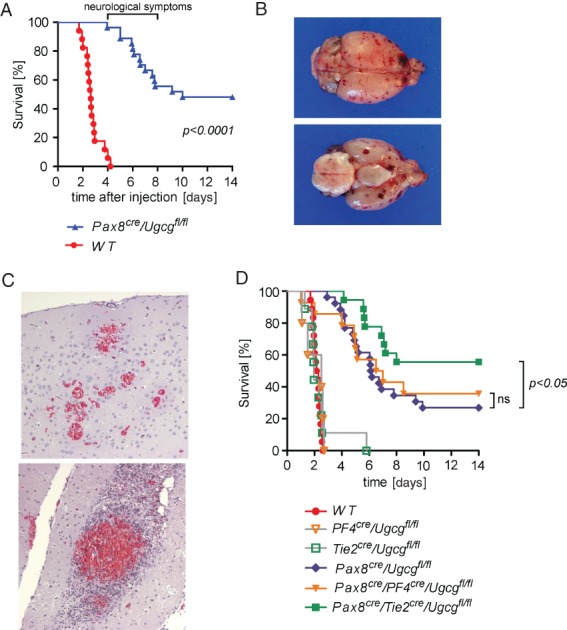

Although Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice survived the first 4 days after the Stx2 injection and did not show either renal failure or blood and urine electrolyte disturbances, severe neurological effects developed, starting at day 4 after the Stx2 injection (Figure 2A). The mice showed neurological symptoms with general weakness, abnormal gait, tremor and seizures, and 50% of them died during the next 4 days. Autopsy demonstrated a diffuse cerebral purpura (Figure 2B, C) resembling human thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (Moschcowitz syndrome).

Figure 2.

Mice lacking the Stx2-receptor Gb3 in tubular epithelium developed cerebral purpura after Stx2-injection. (A) Although Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice were protected from kidney failure and electrolyte dysregulation (shown in Figure 1F), severe and partially fatal neurological symptoms occurred 4–8 days after the Stx2 injection. (B, C) Autopsy revealed diffuse cerebral purpura (B) with bleeding and cerebral TMA; Goldner's trichrome staining, visualizing red blood cells in the haemorrhage foci; magnification = ×200. (D) Depletion of Gb3 in endothelial cells in addition to the tubular cells (Pax8cre/Tie2cre/Ugcgfl/fl, green line) conferred a partial protection from cerebral purpura and improved survival significantly as compared to pure tubular depletion of Gb3 (Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl, blue line). In contrast, depletion of Gb3 in platelets in addition to tubular cells (Pax8cre/PF4cre/Ugcgfl/fl, yellow line) did not prove to be protective. As expected, mice with Gb3 deficiency solely in platelets or endothelial cells (PF4cre/Ugcgfl/fl and Tie2cre/Ugcgfl/fl, respectively) died during the early phase, contemporarily with the Stx2-exposed WT mice.

Considering that platelets 37 and murine cerebral endothelium 38 express Gb3 and thus come into question as potential initiators of the observed cerebral thrombosis, we tested whether an additional depletion of Gb3 in platelets or endothelial cells would alleviate the cerebral purpura. For this purpose, Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice were crossed with a strain expressing Cre in either platelets (PF4cre) or endothelial cells (Tie2cre). The additional depletion of Gb3 in platelets (Pax8cre/PF4cre/Ugcgfl/fl) did not ameliorate the cerebral purpura and did not improve the survival of animals (Figure 2D). However, introducing the inducible endothelial-specific Gb3 deficiency in PAX8cre/Tie2cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice ameliorated the cerebral purpura and significantly improved survival (Figure 2D).

Investigations of STEC-infected patients

We studied the disease course and kidney biopsies in patients with STEC infection at the University Hospital in Frankfurt am Main, Germany (Table1). All cases (nine females and two males) were admitted during the German 2011 epidemic during 12–28 May 2011 and presented with diarrhoea. The median time between diarrhoea onset and the initial admission was 4 (range 0–10) days. Upon the initial admission, median creatinine was 0.84 (range 0.48–17.60) mg/dl, platelet count 216 (range 35–380) × 109/l, haemoglobin 13.8 (range 5.8–17.7) g/dl and LDH 278 (range 175–1994) U/l. Stx2-producing E. coli O104:H4 was detected in the stools of eight patients. All patients showed neurological symptoms, such as headache (n = 3), cognitive defects (n = 10), aphasia (n = 1), paresis (n = 2), seizures (n = 3) and coma (n = 1). During the following days, platelet count decreased to 33 × 109/l, haemoglobin to 6.2 g/dl, LDH rose to 1944 U/l and creatinine to 6.34 mg/dl, corresponding to an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 8.5 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Table1). The patients showed slightly decreased levels of complement factor C3 (average of the lowest C3 level 71 mg/dl; normal values 90–180 mg/dl) and complement C4 levels in the lower normal range (average of the lowest C4 level 11 mg/dl; normal values 10–40 mg/dl).

Table 1.

Clinical parameters in comparison to other cohorts treated with eculizumab or immunoadsorption during the 2011 German epidemic

| Frankfurt cohort | Kielstein et al25 | Menne et al26 | Greinacher et al53 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| n | 11 | 193 | 67 | 12 |

| Age (years) | 30 (#22–44) | 45 | 50.6 | 51 |

| Gender (females, %) | 9 (82) | 146 (75.6) | 56 (84) | 11 (92) |

| Creatinine, highest (mg/dl) | 6.34 (#1.3–17.6) | 4.9 | 2.55* | n.r. |

| Platelets, lowest (109/l) | 33 (#19–124) | 30 | 57.6* | 38 |

| Haemoglobin, lowest (g/dl) | 6.2 (#5.2–7.8) | 6.3 | 11.6* | n.r. |

| LDH, highest (U/l) | 1944 (#753–2792) | 1437 | 1160* | 1500 |

| Severe neurological symptoms** (n, %) | 4 (36.4) | 76 (39.4) | 16 (24) | 6 (50) |

| Therapy | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation (n, %) | 3 (27.3) | 67 (34.7) | 23 (34) | 9 (75) |

| Red blood cell transfusion (n, %) | 11 (100) | 103 (53.4) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Dialysis requirement (n, %) | 9 (82) | 145 (75.1) | 51 (76.1) | 10 (83) |

| Dialysis duration (days) | 18.5 (#4–28) | n.r. | n.r. | 18.3 |

| Eculizumab administration (n, %) | 0 | 193 (100) | 67 (100) | 8 (67) |

| Immunoadsorption (n, %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (100) |

| Plasmapheresis (n, %) | 10 (91) | 193 (100) | 66 (98.5) | 10 (83) |

| Outcome | ||||

| Hospital stay duration (days) | 33 (#19–40) | 27 | 31.2 | n.r. |

| Overall mortality (n, %) | 0 | 5 (2.6) | 3 (5) | 0 |

| Dialysis at discharge (n, %) | 0 | 9 (4.7) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Creatinine, discharge (mg/dl) | 1.39 (#0.8–2.8) | 1.4 | 1.74 | n.r. |

| Creatinine, 6 months (mg/dl) | 0.92 (#0.79–1.6) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Creatinine, 12 months (mg/dl) | 0.91 (#0.8–1.52) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Creatinine, 24 months (mg/dl) | 0.90 (#0.66–1.27) | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Platelets, discharge (109/l) | 215 (#114–342) | 266 | n.r. | n.r. |

| Neurological symptoms, discharge (n, %) | 0 | 5 (2.6) | n.r. | 2 (16.6) |

Values for the first day of plasmapheresis.

Seizures, paresis or coma.

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; n.r., not reported; #, range.

Parameters are expressed as median or as proportion, as appropriate.

Therapy and outcome

All patients received supportive therapy (Table1). Nine patients required haemodialysis for a mean time period of 18.5 days. All 11 patients received red blood cell transfusion and in 10 plasmapheresis was performed because of an elevation of LDH > 800 U/l and/or severe neurological symptoms, such as seizures, paresis or coma. In three patients, mechanical ventilation was necessary. Supportive treatment did not include antibiotic therapy primarily. However, during the hospital stay, eight patients received antibiotics because of suspected nosocomial infection. None of the patients were treated with eculizumab or immunoadsorption.

The patients were discharged after a median period of 33 days with no dialysis requirement and no neurological symptoms. Upon discharge, the median creatinine was 1.39 mg/dl. A 2 year follow-up showed stable kidney function with creatinine levels of 0.92, 0.91 and 0.90 mg/dl, 6, 12 and 24 months, respectively, after discharge.

Kidney biopsies

A kidney biopsy was performed in 10 of 11 patients at a median of 12 (range 6–22) days after the first dialysis, in order to decide on potential anti-complement therapy. At this time point, 22 (range 8–33) days elapsed from the onset of the diarrhoea (Table2). At the time of biopsy, six patients required dialysis and the median platelet count was 161 (range 102–285) × 109/l and the median LDH was 239 (range 165–412) U/l.

Table 2.

Clinical and histological data.

| Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Time from the onset of diarrhoea to biopsy (days) | 22 | 8–33 |

| Time from the first dialysis to biopsy (days) | 12 | 6–22 |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| n | 10 | |

| Age (years) | 30 | 22–44 |

| Females (%) | 8 (80) | |

| Biochemical parameters at the time of kidney biopsy | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.08 | 1.2–7.44 |

| Platelet count (109/l) | 161 | 102–285 |

| LDH (U/l) | 239 | 165–412 |

| Haemodialysis (n, %) | 6 (60) | |

| Histological evaluation | ||

| Tubular epithelial flattening (n, %) | 10 (100) | |

| Tubular epithelial vacuolization (n, %) | 10 (100) | |

| Tubular intraluminal cell debris (n, %) | 5 (50) | |

| Chronic tubular damage and interstitial fibrosis (% area of cortex) | 3 | 0–10 |

| Glomeruli/biopsy | 12 | 6–41 |

| Percentage of segmentally sclerosed glomeruli (%) | 13 | 0–33 |

| Percentage of globally sclerosed glomeruli (%) | 7 | 0–63 |

| Glomerular intracapillary thrombi (n, %) | 4 (40) | |

| Glomerular intracapillary fragmentocytes (n, %) | 6 (60) | |

| Glomerular intracapillary mononuclear cells (n, %) | 5 (50) | |

| Glomerular intracapillary granulocytes (n, %) | 4 (40) | |

| Glomerular endothelial swelling (n, %) | 90 (90) | |

| Widening of the subendothelial space (n, %) | 6 (60) | |

| Loss of endothelial fenestrae (n, %) | 8 (80) | |

| Mesangial matrix expansion (n, %) | 6 (60) | |

| Mesangiolysis (n, %) | 8 (80) | |

| Podocyte swelling (n, %) | 3 (30) | |

| Arteriolar endothelial swelling (n, %) | 5 (50) |

Parameters are expressed as median or as proportions, as appropriate.

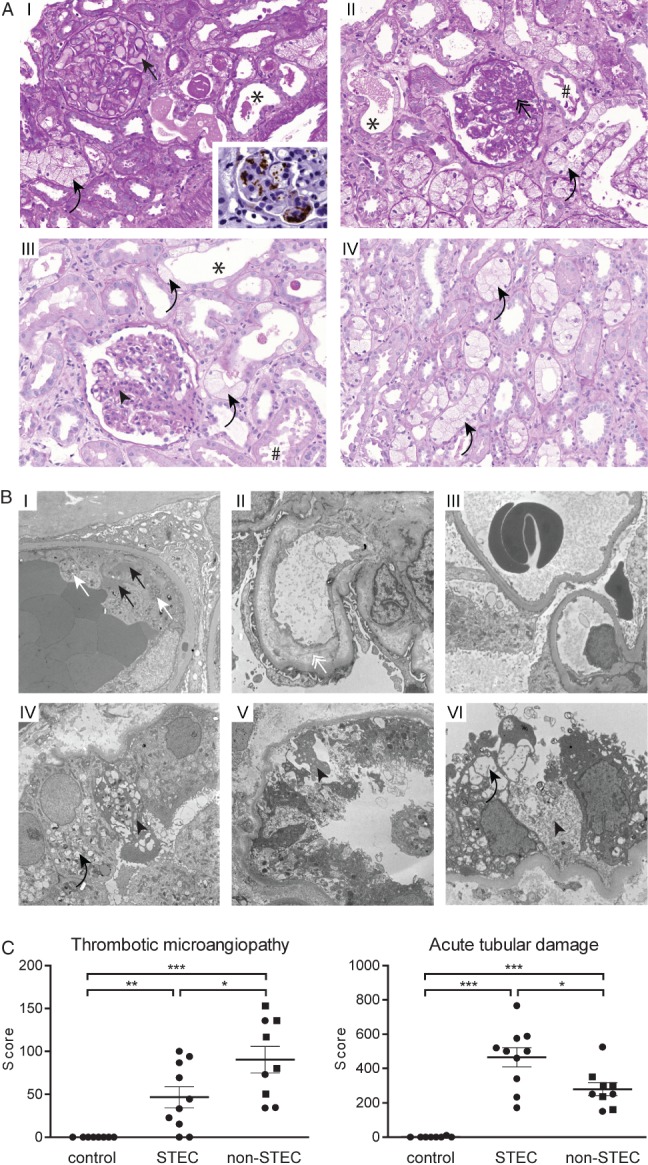

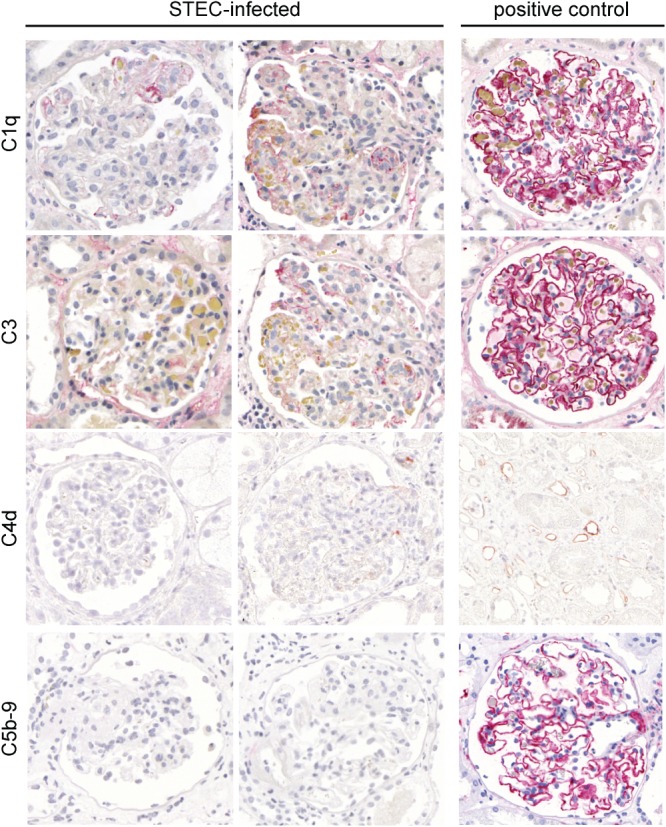

Light microscopy revealed a median of 12 glomeruli/biopsy, of which, on average, 7% were globally and 13% segmentally sclerosed. With Goldner's trichrome staining, fragmented erythrocytes could be detected in six (60%) patients (Table2, Figure 3). Mesangiolysis was detectable in eight (80%) patients. Electron microscopy visualized glomerular endothelial damage manifested as absence of fenestrae in eight (80%) patients and an electrolucent broadening of the subendothelial space in six (60%) biopsies (Table2, Figure 3). Also in those cases, which showed ongoing TMA by conventional and electron microscopy, only faint staining for complement factors C1q and C3 could be detected by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4). In immunohistochemistry for C4d and C5b-9, no signal was observed, despite the positivity of the corresponding positive controls (Figure 4). In two patients (20%), no signs of acute or past TMA could be detected by light and electron microscopy, despite reduced kidney function (peak creatinine 1.3 and 9.1 mg/dl, respectively) (Table2, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In addition to TMA, STEC-infection caused a profound tubular injury in man. (A) Light microscopy: a part of the biopsies showed glomeruli with congested capillaries filled with red bold cells (I, black arrow) and platelet-containing thrombotic material, visualized as a brown signal in CD61 immunohistochemistry (I, inlay). Other cases predominantly showed glomeruli with segmental sclerosis and wrinkling and collapse of capillaries (II, black double arrow), indicating a preceding but not active TMA. Glomeruli of other biopsies had almost normal architecture, with only a slight mesangial matrix increase (III, black arrowhead). A constant finding in all biopsies was a pronounced acute tubular damage, manifested as epithelial flattening (*) and/or presence of intraluminal cell detritus (#) and/or pronounced vacuolization (I–IV, black curved arrows); PAS staining, magnification = ×250. (B) Transmission electron microscopy of glomeruli (I–III) and tubular epithelium (IV–VI). Active TMA was documented by the presence of thrombotic material composed of platelets (I, white arrows) and fibrin strands (I, black arrows) in glomerular capillaries. Endothelial damage was manifested as absence of endothelial fenestrae and widening of the subendothelial space (II, white double arrow). In two patients the glomeruli showed normal architecture (III). Ultrastructural correlates of the pronounced tubular damage manifested as vacuolization (IV and VI, black curved arrows) and epithelial necrosis (IV–VI, black arrowheads); electron micrographs, lead citrate/uranyl acetate staining; magnification = (glomeruli) × 5000; (tubules) × 6300. (C) The extent of the glomerular TMA and acute tubular damage were compared between normal kidney tissue (tumour-free parts of tumour nephrectomies, control, n = 8), kidney biopsies from STEC-infected patients (STEC, n = 10) and randomly chosen biopsies from patients with STEC-unrelated TMA (non-STEC, n = 9; individuals > 45 years are depicted as squares). Glomerular TMA was semi-quantified on a PAS-stained slide by scoring the extent of TMA in each glomerulus. Acute tubular damage was assessed by building a score reflecting the following three criteria: brush border loss in proximal tubules; epithelial cell flattening; and vacuolization. Although the extent of TMA was less, the tubular damage was significantly higher in the STEC group than in the non-STEC group; data are shown as mean ± SEM; statistical differences were tested by two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry for complement factors in glomeruli of patients infected with STEC. In the glomeruli of patients with STEC-elicited TMA, the presence of complement factors C1q, C3, C4 and C5b-9 (membrane attack complex) was investigated by immunohistochemistry (alkaline phosphatase/anti-alkaline phosphatase; APAAP method). For C1q, C3 and C5b-9, membranous glomerulopathy served as a positive control. For C4d, an AB0-incompatible kidney transplant showing staining in the peritubular capillaries was used as a positive control. In contrast to the strong staining in the positive control, only faint focal segmental staining for C1q and C3 was detected in STEC-associated TMA. For C4d and C5b-9, virtually no staining was observed in STEC-infected patients; magnification = ×400

Analysis revealed moderate to severe tubular epithelial damage manifested as loss of the brush border, epithelial cell flattening and vacuolization, which focally progressed to epithelial necrosis, in all 10 biopsies (Figure 3). Although in the STEC-infected patients the extent of TMA was lower, the tubular damage was significantly higher than in randomly chosen biopsies of patients with TMA with a STEC-unrelated aetiology (Figure 3C; see also supplementary material, Table S1).

In STEC-infected patients, the tubular epithelium showed significantly increased apoptosis with consecutively increased proliferation (Figure 5). In addition, CD44, which is known to be up-regulated by renal tubular epithelial cells in response to various stress stimuli and β-catenin, which is an important regulator of cell–cell adhesion and signalling, were also significantly up- or down-regulated, respectively, in the tubular epithelium of STEC patients as compared to control renal parenchyma (Figure 5). Moreover, the apoptosis and proliferation rates, as well as the up-regulation of CD44, were significantly higher in patients with STEC-induced than with STEC-unrelated TMA (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical findings of the STEC-associated acute tubular damage. Expression of cleaved caspase 3, Ki67, β-catenin and CD44 were studied by immunohistochemistry in STEC-infected patients (n = 10) and compared to normal kidney tissue from tumour nephrectomies (control, n = 8) and to kidney biopsies with TMA due to a STEC-unrelated aetiology (non-STEC, n = 9). The acute tubular damage was associated with a significant increase in apoptosis (visualized by cleaved caspase 3), reactive proliferation (visualized by Ki67) and elevated expression of CD44 in both STEC and non-STEC groups. However, for all three parameters, the increase was significantly higher in the STEC than in the non-STEC group. In the STEC group, apoptosis (arrow) and mitosis (arrowhead) could be seen in tubular epithelial cells; β-catenin was significantly down-regulated in renal tubular epithelium of both STEC and non-STEC patients, to a similar extent; magnification = ×100. In the case of immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase 3 and Ki67, the number of positive tubular cells was counted and expressed as average cell number/high power field (HPF; ×40 objective, ×10 ocular). For evaluation of the immunohistochemistry for β-catenin and CD44, semiquantitative scoring of the staining intensity of tubular cells in each HPF of the biopsy was performed; in the non-STEC group, individuals > 45 years are depicted as squares. Statistical differences were tested by two-tailed Mann–Whitney test; ns, non-significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Impact of Stx2 on human tubular epithelial cells

Humans show expression of Gb3 in all nephron segments (see supplementary material, Figure S4). To analyse the effects of Stx2 on human tubular epithelium in vitro, experiments were performed on the human proximal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2. These cells expressed the Stx2 receptor Gb3 (Figure 6A) and treatment with Stx2 resulted in a significantly increased time- and dose-dependent apoptosis (Figure 6B). Moreover, Stx2 led to an up-regulation of interleukin 8 (IL8), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) and regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted (RANTES) (Figure 6C). With the exception of MCP1, the co-administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) did not further increase the production of these cytokines (Figure 6C). The production of these cytokines under the influence of Stx2 was also mirrored by an increased infiltration of granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages and T cells in kidney biopsies from STEC-infected patients (Figure 6D). For monocytes/macrophages and T cells, this infiltration was significantly higher in STEC-infected patients than in individuals with STEC-unrelated TMA (Figure 6D), thus suggesting that the observed effects of Stx2 on tubular epithelial cells are not merely a secondary phenomenon of glomerular TMA.

Figure 6.

Stx2 effects on human tubular epithelial cells and on interstitial inflammation. (A) Thin-layer chromatography immuno-overlay demonstrated the presence of the Stx2 receptor Gb3 on the human renal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2. Glycosphingolipid aliquots from the HK-2 cells were applied for Gb3 detection, using polyclonal anti-Gb3 antibody (lane I) and Stx2 (lane II). An equimolar mixture of Gb3 and Gb4 (10 µg), prepared from human erythrocytes, served as standard (Std); the two bands of Gb3 are due to different chain lengths of fatty acids in the ceramide portion of Gb3. (B) Apoptosis under the influence of Stx2 was investigated in HK-2 cells; these were exposed for 24, 48 and 72 h to cell culture medium alone (control) or Stx2 at 20 or 100 ng/ml. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry as the proportion of Annexin V-positive cells. Stx2 led to a time- and dose-dependent increase of apoptosis in HK-2 cells (n = 4). (C) Expression of selected cytokines in HK-2 cells in response to Stx2 and LPS was investigated; to this end, cells were exposed to Stx2 (100 ng/ml) and/or LPS (1 µg/ml) for 6 h and the expression of IL8, MCP1, RANTES and GAPDH was measured by quantitative RT–PCR. Whereas Stx2 increased the expression of all three cytokines, no further elevation was observed for IL8 and RANTES when the cells were also treated with LPS (n = 3). (D) The presence of granulocytes [positive for chloracetate esterase (CAE)], monocytes/macrophages (CD68-positive) and T cells (CD3-positive) was quantified in kidney biopsies of STEC-infected patients (STEC, n = 10) and compared to normal kidneys (non-tumourous parts of tumour nephrectomies, control, n = 8) and biopsies from patients with STEC-unrelated TMA (non-STEC, n = 9). Whereas the granulocytic infiltrate was elevated in both the STEC and non-STEC groups to a similar extent, a significantly higher increase was observed for monocytes/macrophages and T cells in the STEC than in the non-STEC group; in the non-STEC group, individuals > 45 years are depicted as squares. In (B, C) statistical differences were tested by two-tailed Student's t-test; in (D) two-tailed Mann–Whitney test was used: data are shown as mean ± SEM; n.s., non-significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Discussion

Humans express the Stx2 receptor Gb3 not only on renal endothelial but also on tubular cells (see supplementary material, Figure S4). We were intrigued by the idea, also supported by experimental data from other groups, that there might be additional pathophysiological mechanisms independent of glomerular TMA by which Stx2 would cause acute kidney failure in humans 39–43. In order to dissect direct Stx2-elicited tubulotoxic effects from secondary effects mediated by upstream glomerular TMA, we applied a mouse model of Stx2 toxicity. As shown by others and ourselves, in the kidneys of WT mice, Gb3 expression is limited to collecting ducts but is absent from renal endothelial cells (Figure 1; see also supplementary material, Figures S1, S2 42–44). The lack of Gb3 in murine renal endothelium and its pure tubule-specific expression are further supported by the facts that: (a) in mice with Fabry disease (lysosomal storage disease characterized by defective degradation of Gb3), no Gb3 accumulates in renal endothelial cells 45; and (b) no residual Gb3 is present in murine kidneys when genetically depleting it from tubular cells 46.

The absence of Gb3 from murine renal endothelial cells excluded the possibility that, upon administration of Stx2, potential secondary effects on the tubular epithelium would occur as a result of glomerular TMA. Although glomerular TMA has been reported in Stx2-injected mice by others (with or without co-administering LPS), ultrastructural evidence and appropriate controls have not been provided 38,47,48. We could not detect any TMA in moribund Stx2-injected WT mice (Figure 1C). This is not surprising, in view of that fact that murine glomerular endothelium did not express Gb3 (Figure 1A; see also supplementary material, Figure S1 42). Instead, we found that 36 h after the Stx2-injection, WT mice showed a profound hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia, which were accompanied by an inverse change of these electrolytes in the urine (Figure 1F), thus indicating initial severe tubular failure. This confirms the previous findings of Wadolkowski et al 39 and Tesh et al 40, who pinpointed acute tubular damage without any TMA in STEC-infected and Stx2-injected mice, respectively. The results are also congruent with previous observations of polyuria in Stx2-injected rats 41 and an increased urine production and apoptosis of the collecting duct epithelium in Stx2-injected mice 42,43.

In order to demonstrate that these tubular changes are causal and do not represent an epiphenomenon (eg from prerenal causes or hormone disturbances due to adrenal or central nervous toxicity), we applied a transgenic mouse model which generated a pure tubular deficiency of Gb3 (Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl), thereby allowing Stx2 to exert its effects on all but tubular epithelial cells. These mice were fully protected from acute renal failure and electrolyte disturbances (Figure 1F), thus providing further evidence for a direct toxicity of Stx2 towards the renal tubular epithelium in vivo. The protection from tubular dysfunction in the Pax8cre/Ugcgfl/fl mice in turn allowed the development of cerebral purpura at days 4–8 after Stx2 injection, ie at a time point not reached by WT mice because of death due to kidney failure (Figure 2A–C). The cerebral purpura and animal survival were ameliorated by an additional deficiency for Gb3 in the endothelium (Pax8cre/Tie2cre/Ugcgfl/fl) (Figure 2D), indicating that Stx2 toxicity towards the brain microcirculatory endothelium and the renal tubular epithelia are leading to different organ manifestations of the same disease. Interestingly, Bridgwater et al 49 have described small vessel damage with consecutive haemorrhages in the grey matter of rabbits upon injection of Shigatoxin.

Most studies addressing the effects of Stx2 on human kidneys have been based on analysis of autopsies, which do not allow a differentiation between the prefinal renal damage, post mortem autolysis, potential vascular and glomerular disease-associated tubular damage and direct tubulotoxicity. We documented in 10 living STEC-infected patients, who were biopsied during the acute disease course, that an acute and potentially reversible tubular damage is also a constant finding in humans. Whereas histological signs of recent TMA did not represent a constant finding in these patients, all cases presented with moderate to severe acute tubular damage (Table2, Figures 5). One might surmise that the acute tubular damage represented a secondary effect of the upstream glomerular TMA. Although the latter was certainly a contributor to acute tubular damage, we provide several lines of evidence for direct Stx2 tubulotoxicity. First, the extent of the acute tubular damage was higher in STEC-infected patients than in individuals with STEC-unrelated TMA, although the extent of TMA was higher in the latter group (Figure 3C). In agreement with a previous report 50 we could show, in an isolated cell culture system in vitro, that tubular epithelia, which express the Stx2 receptor Gb3, undergo apoptosis under the influence of Stx2 (Figure 6A, B). In addition, in tubular cells in vitro, Stx2 elicited secretion of cytokines (IL8, MCP1 and RANTES) which could be associated with an increased infiltration of granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages and T cells in the kidneys of patients suffering from a STEC-related, as compared to STEC-unrelated, disease (Figure 6C, D). This finding is supported by previous studies on baboons, which showed an increased production of cytokines (including IL8 and MCP1) in kidneys upon Stx2 injection 14. Similarly, we could detect that processes such as tubular CD44 up-regulation and β-catenin down-regulation, which were previously implicated in different models of Stx toxicity 51,52, play also a role in the human disease (Figure 5).

Although the cohort presented here was comparable for most parameters with the eculizumab-treated groups in other studies 25,26 and with immunoadsorption-treated patients 53 (Table1), a resolution of neurological symptoms and a restoration of kidney function were achieved in all our patients without eculizumab administration. The acute tubular damage and the high regenerative capacity of tubular epithelia probably contributed to the fact that the severely deteriorated kidney function was restored completely. This is also in line with the clinical observation that supportive care and an early volume expansion mitigate Stx-associated kidney failure and shorten the duration of hospitalization 54,55. Immunohistochemistry did not reveal any presence of the complement factors C5b–9, thus strengthening the notion that persistent complement activation may not play a prominent role. Interestingly, also in a non-human primate model, no increase in the soluble C5b–9 could be found during Stx1- and Stx2-elicited TMA 56. The lack of a significant complement activation might explain why reports from the 2011 German epidemic 25,26 failed to reveal any benefit of eculizumab treatment. On the other hand, this epidemic differed from past ones by predominantly (88%) affecting adults, while the initial use of eculizumab for STEC-infected patients was reported on three 3 year-old infants 24, which, in contrast to adults, might have a more pronounced expression of the Stx2-receptor on the glomerular endothelium 57.

In summary, we have provided experimental and clinical data that strengthen the hypothesis that acute tubular damage might represent an additional, and until now underestimated, pathophysiological mechanism of kidney failure after exposure to Stx2. As implicated by the mouse experiments, this tubular damage reflects a primary Stx2 toxicity towards the tubular epithelium. The excellent outcome in all of our 11 patients showed that optimized supportive therapy is likely to suffice for the regeneration of tubular damage and the full recovery of kidney function, and that the treatment of adults, even with severe renal involvement, may not necessarily require complement inhibition.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; Grant Nos SFB 938 to HJG and SP, and MU845/4-2 to JM) and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF; Münster Project, Grant No. Müth2/028/10).

Author contributions

SP, HJG and CB designed the research; SP, GF, RJ, JM and NG performed experiments; SP, EG, SB, NO, OJ, IAH, HG and CB collected and analysed the data; and SP, HJG and CB wrote the manuscript.

Abbreviations

CAE, chloracetate esterase; Gb3, globotrihexosylceramide; HUS, haemolytic uraemic syndrome; IL8, interleukin 8; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCP1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; RANTES, regulated upon activation normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted; STEC, Shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli; Stx, Shigatoxin; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; WT, wild-type.

Supporting Information

The following supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article

Supplementary materials and methods

Expression of Gb3 in native and LPS-injected mice

Segment-specific expression of Gb3 in mice

Immunohistochemistry for C3 in Stx2-injected mice

Expression of Gb3 in human kidneys

Supplementary materials and methods

References

- 1.Riley LW, Remis RS, Helgerson SD, et al. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karmali MA, Petric M, Lim C, et al. The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:775–782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MMWR. Update: multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections from hamburgers – western United States, 1992–1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 42:258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michino H, Araki K, Minami S, et al. Massive outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in schoolchildren in Sakai City, Japan, associated with consumption of white radish sprouts. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:787–796. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorpe CM. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1298–1303. doi: 10.1086/383473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trachtman H, Austin C, Lewinski M, et al. Renal and neurological involvement in typical Shiga toxin-associated HUS. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:658–669. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obrig TG. Escherichia coli Shiga toxin mechanisms of action in renal disease. Toxins (Basel) 2011;2:2769–2794. doi: 10.3390/toxins2122769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank C, Werber D, Cramer JP, et al. Epidemic profile of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1771–1780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, et al. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:671–676. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellmann A, Harmsen D, Cummings CA, et al. Prospective genomic characterization of the German enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak by rapid next-generation sequencing technology. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasko DA, Webster DR, Sahl JW, et al. Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic–uremic syndrome in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd B, Lingwood C. Verotoxin receptor glycolipid in human renal tissue. Nephron. 1989;51:207–210. doi: 10.1159/000185286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentz EK, Leyva-Illades D, Lee M-S, et al. Differential response of the human renal proximal tubular epithelial cell line HK-2 to Shiga toxin types 1 and 2. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3527–3540. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05139-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Oh SY, Cherla RP, et al. Distinct renal pathology and a chemotactic phenotype after enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli Shiga toxins in non-human primate models of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1227–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morigi M, Buelli S, Zanchi C, et al. Shigatoxin-induced Endothelin-1 expression in cultured podocytes autocrinally mediates actin remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1965–1975. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johannes L, Mayor S. Induced domain formation in endocytic invagination, lipid sorting, and scission. Cell. 2010;142:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg AX, Suri RS, Barrowman N, et al. Long-term renal prognosis of diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;290:1360–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mead PS, Griffin PM. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Lancet. 1998;352:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasser C, Gautier E, Steck A, et al. Hemolytic–uremic syndrome: bilateral necrosis of the renal cortex in acute acquired hemolytic anemia. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1955;85:905–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, et al. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1233–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1676–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nurnberger J, Philipp T, Witzke O, et al. Eculizumab for atypical hemolytic–uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:542–544. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0808527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapeyraque AL, Malina M, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, et al. Eculizumab in severe Shiga toxin-associated HUS. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2561–2563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1100859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kielstein JT, Beutel G, Fleig S, et al. Best supportive care and therapeutic plasma exchange with or without eculizumab in Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic–uraemic syndrome: an analysis of the German STEC–HUS registry. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2012;27:3807–3815. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menne J, Nitschke M, Stingele R, et al. Validation of treatment strategies for enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic uraemic syndrome: case–control study. Br Med J. 2012;345:e4565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porubsky S, Schmid H, Bonrouhi M, et al. Influence of native and hypochlorite-modified low-density lipoprotein on gene expression in human proximal tubular epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:2175–2187. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63775-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leder L. On the selective enzyme-cytochemical demonstration of neutrophilic myeloid cells and tissue mast cells in paraffin sections. Klin Wochenschr. 1964;42:553. doi: 10.1007/BF01486688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betz J, Bielaszewska M, Thies A, et al. Shiga toxin glycosphingolipid receptors in microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells: differential association with membrane lipid raft microdomains. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:618–634. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M010819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jennemann R, Sandhoff R, Wang S, et al. Cell-specific deletion of glucosylceramide synthase in brain leads to severe neural defects after birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12459–12464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500893102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porubsky S, Speak AO, Salio M, et al. Globosides but not isoglobosides can impact the development of invariant NKT cells and their interaction with dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:3007–3017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouchard M, Souabni A, Busslinger M. Tissue-specific expression of cre recombinase from the Pax8 locus. Genesis. 2004;38:105–109. doi: 10.1002/gene.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forde A, Constien R, Grone HJ, et al. Temporal Cre-mediated recombination exclusively in endothelial cells using Tie2 regulatory elements. Genesis. 2002;33:191–197. doi: 10.1002/gene.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiedt R, Schomber T, Hao-Shen H, et al. Pf4–Cre transgenic mice allow the generation of lineage-restricted gene knockouts for studying megakaryocyte and platelet function in vivo. Blood. 2007;109:1503–1506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan MJ, Johnson G, Kirk J, et al. HK-2: an immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;45:48–57. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthing J, Schweppe CH, Karch H, et al. Shiga toxins, glycosphingolipid diversity, and endothelial cell injury. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:252–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooling LL, Walker KE, Gille T, et al. Shiga toxin binds human platelets via globotriaosylceramide (Pk antigen) and a novel platelet glycosphingolipid. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4355–4366. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4355-4366.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuda T, Tokuda N, Numata S, et al. Targeted disruption of Gb3/CD77 synthase gene resulted in the complete deletion of globo-series glycosphingolipids and loss of sensitivity to verotoxins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10230–10235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadolkowski EA, Sung LM, Burris JA, et al. Acute renal tubular necrosis and death of mice orally infected with Escherichia coli strains that produce Shiga-like toxin type II. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3959–3965. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3959-3965.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tesh VL, Burris JA, Owens JW, et al. Comparison of the relative toxicities of Shiga-like toxins type I and type II for mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3392–3402. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3392-3402.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugatani J, Komiyama N, Mochizuki T, et al. Urinary concentrating defect in rats given Shiga toxin: elevation in urinary AQP2 level associated with polyuria. Life Sci. 2002;71:171–189. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Psotka MA, Obata F, Kolling GL, et al. Shiga toxin 2 targets the murine renal collecting duct epithelium. Infect Immun. 2009;77:959–969. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00679-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutjes NW, Binnington BA, Smith CR, et al. Differential tissue targeting and pathogenesis of verotoxins 1 and 2 in the mouse animal model. Kidney Int. 2002;62:832–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujii Y, Numata S, Nakamura Y, et al. Murine glycosyltransferases responsible for the expression of globo-series glycolipids: cDNA structures, mRNA expression, and distribution of their products. Glycobiology. 2005;15:1257–1267. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porubsky S, Jennemann R, Lehmann L, et al. Depletion of globosides and isoglobosides fully reverts the morphologic phenotype of Fabry disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1922-9. (in press); doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1922-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stettner P, Bourgeois S, Marsching C, et al. Sulfatides are required for renal adaptation to chronic metabolic acidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9998–10003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217775110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morigi M, Galbusera M, Gastoldi S, et al. Alternative pathway activation of complement by Shiga toxin promotes exuberant C3a formation that triggers microvascular thrombosis. J Immunol. 2011;187:172–180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sauter KAD, Melton-Celsa AR, Larkin K, et al. Mouse model of hemolytic–uremic syndrome caused by endotoxin-free Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) and protection from lethal outcome by anti-Stx2 antibody. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4469–4478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00592-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bridgwater FA, Morgan RS, Rowson KE, et al. The neurotoxin of Shigella shigae: morphological and functional lesions produced in the central nervous system of rabbits. Br J Exp Pathol. 1955;36:447–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burlaka I, Liu XL, Rebetz J, et al. Ouabain protects against Shiga toxin-triggered apoptosis by reversing the imbalance between Bax and Bcl-xL. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1413–1423. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012101044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takenouchi H, Kiyokawa N, Taguchi T, et al. Shiga toxin binding to globotriaosyl ceramide induces intracellular signals that mediate cytoskeleton remodeling in human renal carcinoma-derived cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3911–3922. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sibalic V, Fan X, Loffing J, et al. Upregulated renal tubular CD44, hyaluronan, and osteopontin in kdkd mice with interstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 1997;12:1344–1353. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.7.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greinacher A, Friesecke S, Abel P, et al. Treatment of severe neurological deficits with IgG depletion through immunoadsorption in patients with Escherichia coli O104:H4-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome: a prospective trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1166–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ardissino G, Tel F, Testa S, et al. Role of early volume expansion in mitigating Shigatoxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Atlanta: In American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ake JA, Jelacic S, Ciol MA, et al. Relative nephroprotection during Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: association with intravenous volume expansion. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e673–680. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee BC, Mayer CL. Leibowitz CS, et al. Quiescent complement in nonhuman primates during E. coli Shiga toxin-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood. 2013;122:803–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaisri U, Nagata M, Kurazono H, et al. Localization of Shiga toxins of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in kidneys of paediatric and geriatric patients with fatal haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Microb Pathog. 2001;31:59–67. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of Gb3 in native and LPS-injected mice

Segment-specific expression of Gb3 in mice

Immunohistochemistry for C3 in Stx2-injected mice

Expression of Gb3 in human kidneys

Supplementary materials and methods